Abstract

The aim of this study is to generate a grounded theory explaining patterns of behavior among health care professionals (HCPs) during interactions with patients in outpatient respiratory medical clinics. The findings suggest that the HCPs managed contradictory expectations to the interaction by maintaining a distinction between possible and impossible topics to counseling. Three subcategories explaining the effort that maintain the impossible and possible topics separated were identified: (a) an effort to maintain the diseased lungs as the main task in counseling, (b) navigating interactions to avoid strong emotions of suffering in patients to reveal, (c) avoiding the appearance of the non-alterable life circumstances of the patients. The HCPs’ attitudes toward what patients could be offered generated a distance and a difficulty during counseling and created further suffering in the patients but likewise a discomfort and frustration among the HCPs.

Keywords: communication; grounded theory; health care professionals; illness and disease, chronic; relationships, patient-provider; research qualitative; social constructionism

Introduction

In Western countries, many patients suffering from severe chronic respiratory diseases (CRDs) are followed in the outpatient respiratory medical clinic (ORMC) on a regular basis. Typically, the patient is referred to the ORMC following discharge from a hospital department or by a general practitioner to clarify or process diagnosis, rehabilitation, counseling, and drug treatment. ORMCs are subject to many temporal, structural, and substantive requirements. A short-term and very structured frame characterizes the consultation allocating 15 to 30 minutes for each visit. The primary tasks of health care professionals (HCPs) are dealing with symptoms, preventing deterioration of the condition, and carrying out counseling regarding lifestyle changes. The mandatory content of conversation includes smoking habits, diet, exercise, lung function measurement, screening of functional level, and drug prescription (Parshall et al., 2012; World Health Organization, 2002). All subjects and activities must be documented in the hospital records in accordance with the “chronic care model,” international guidelines, and golden standards for treatment and counseling about CRD (Abrosimov et al., 2005; Blands & Bælum, 2007; Cruz et al., 2007). We assume that the extent and the topics of the visit may affect the counselor’s ability to meet the needs of patients and also find opportunities to recognize and listen to patients’ experiences during counseling (Bakker, Schaufeli, Sixma, & Dierendonck, 2000).

There is a growing body of evidence pointing to the physical, mental, and social consequences of CRD affecting the life of patients in many ways (Blands & Bælum, 2007; Cruz et al., 2007). Such problems arise from symptoms of breathlessness, cough, and increased mucus production, which may over time lead to immobility, dependency on relatives and the health care system, and social isolation (Armstrong et al., 2007; Cruz et al., 2007; Giacomini, DeJean, Simeonov, & Smith, 2012; GOLD, 2015; Parshall et al., 2012). Moreover, CRD is associated with an increased risk of anxiety, insomnia, fatigue, anorexia, loneliness, guilt, and depression and a decreased quality of life in patients. Several studies suggest a lack of opportunity in patients to influence the content of interaction with HCPs and a lack of attachment and emotional responsiveness in the HCPs to engage the concerns of the patients in the clinical encounter (Borge, Wahl, & Moum, 2010; Ek, Sahlberg-Blom, Andershed, & Ternestedt, 2011; Giot, Maronati, Becattelli, & Schoenheit, 2013; Gysels & Higginson, 2010; Karakurt & Ünsal, 2013; Kvangarsnes, Torheim, Hole, & Öhlund, 2013; Lindquist & Hallberg, 2010). Based on the physical, existence-threatening, and progressive nature of the CRD, there seems to be a growing awareness of the need for more palliative-directed treatment and care. This is the case even though studies have found a lack of palliative-directed conversations regarding hospitalized patients suffering from severe CRD (Bajwah et al., 2013; Bourbeau & Nault, 2004; Chen, Chen, Lee, Cho, & Weng, 2008; Cicutto, Brooks, & Henderson, 2004). Studies suggest that the patients’ perspectives may offer important knowledge to HCPs as to how patients overcome, adapt to, and understand illness when living with a CRD (Ek et al., 2011; Lucius-Hoene, Thiele, Breuning, & Haug, 2012). In addition, many patients seem to have a need to be given the opportunity to express emotions of existential suffering during interactions with HCPs (Anderson, Kools, & Lyndon, 2013; Frank, 1995; Lucius-Hoene et al., 2012).

Over the last several decades, the former authoritative approach of the HCP has been replaced by an ideological and institutional—but likewise vocational—desire to include chronically ill patients in care and treatment (Larsen, Cutchin, & Harsløf, 2013; Rabe et al., 2007; Shim, 2010). Today, being patient oriented is immensely popular among health authorities in many Western countries. This reflects a moral–philosophical approach in which the patient is regarded as unique and the multidimensionality of the human experience of illness is recognized by building on multiple understandings of the patient’s situation (Dubbin, Chang, & Shim, 2013; Epstein, Fiscella, Lesser, & Stange, 2010). Nonetheless, several studies point to the lack of a patient-oriented approach in the patient-HCP interaction (Disler et al., 2014; Wong et al., 2014). A patient-centered approach is described as having the potential to be instrumental in facilitating patients’ coping, managing of self-care, and optimizing quality of life. Conversely, a lack of patient involvement may damage these processes (Gardiner et al., 2010; Gysels & Higginson, 2010; Lawn, Delany, Sweet, Battersby, & Skinner, 2014; Thorne, 2006).

As outlined, we assume that the limited time and many demands of conversation topics may influence what HCPs may experience as achievable during the counseling. In addition, several studies point to external conditions leading to a lack of patient involvement and responsiveness to patients’ concerns (Michaelsen, 2012). These conditions include factors such as increasing work pressure, numerous changes in the structure of tasks, the implementation of new or changed administrative tasks, and increasing demands for documentation (Bakker et al., 2000; Potter, 1983). Bakker et al. (2000) have suggested that the demands of many patients in terms of empathy and emotional recognition of their illness experiences may exhaust people and cause burnout in the HCPs. In summary, the described studies indicate that the conversation may be difficult for several reasons. For one, patients suffering from CRD may experience a lack of response from the HCPs to their needs in difficult life circumstances. The HCPs may experience burnout and frustration regarding patients’ expectations and requirements in a time-pressured working environment. Whether this is the case in the ORMC has not been addressed in other studies so far. There has been a lack of studies exploring the clinical encounter in the ORMC and how the framework for ambulatory services affects the interaction in similar or particular ways (Kayahan, Karapolat, Atyntoprak, & Atasever, 2006; Lange, 2009; Seymour et al., 2010).

Aim

The aim of this study is to generate a grounded theory exploring the pattern of behavior in HCPs during conversations with patients suffering from CRD in the ORMC.

The Study

Participants and Data Collection

Data were collected from 67 field observations on 28 randomly selected days at three ORMCs in Denmark over 26 months from 2012 to 2014. A total of 54 patients suffering from CRD were included in the field observations. In addition, we collected data from 29 HCPs, including 17 nurses and 12 doctors to the extent they performed counseling or treatment of the included patients. Accordingly, all HCPs who performed counseling of patients during the field observations were interviewed individually (n = 29) and in a focus group interview (n = 10). The interviews were performed after the field observations, lasted between 10 and 30 minutes, and were written down by hand as field notes.

The purpose of the interview was to explore initial ideas further or to bring forth data concerning behavior, strategies, or statements that we wanted to investigate further. The patient interviews took place in the patients’ homes or by phone call and lasted between 25 minutes and 3 hours. Meanwhile, the interviews were tape recorded and transcribed verbatim afterward. The interview guide was loosely structured in the beginning and explored issues from the field observations in the ORMCs from both the HCPs’ and the patients’ perspectives. There were five patients who suffered from mild CRD, 10 from moderate CRD, and 15 from severe or very severe CRD based on the HCPs’ assessments. Out of the 30 included patients, 14 were or had been unskilled workers with elementary educations, 10 were artisans/higher education, and three were academics. The HCPs had 1 to 20 years of experience in ORMCs.

Methodology and Data Analysis

The study is based on Charmaz’s social-constructionist interpretation of grounded theory that relies on the pragmatist philosophical tradition informed by symbolic interactionism (Blumer, 1969; Charmaz, 1990, 2004, 2006). Grounded theory methodology offers flexible but systematic guidelines for collecting and analyzing data involving the development of a theory consisting of a set of plausible relationships between concepts and groups of concepts grounded in data. Asking questions and making constant comparisons are basic actions in the grounded theory method. The first act could be considered an analytical tool whose purpose is to open the empirical material so as to create an understanding of the data. We have, for instance, initially applied word-by-word, line-by-line, and incident-by-incident coding providing the analytical tool, which makes it possible to bring the coding process further. In the focused coding, we have used the most significant or frequent earlier codes to sift through and analyze large amounts of collected data. The second action is the constant comparative process. This method stimulates thoughts and opinions about categories of properties and dimensions that make it possible to create a better understanding and thus make sense of the empirical material (Charmaz, 2014). The first author initially coded the entire transcripts and the co-authors reviewed these coded transcripts. Throughout the coding process, the first author wrote analytic memos describing context, conditions, processes, and consequences that the co-authors reviewed.

The coding process led us to identify what was happening in the data and explain the elements of the initial categories. During the field observations, we reflected upon what sense the patients and HCPs made of their own statements and actions and what analytic sense we could make of the emerging patterns of behavior in HCPs. The analysis generated categories that were made more and more abstract as data were gathered to refine the theory. During initial coding, we studied fragments of data—words, lines, segments, and incidents—closely for their analytic import. While engaged in focused coding, we selected what seemed to be the most useful initial codes and tested them against extensive data. The process of data collection and initial and focused coding ended when the categories were saturated and when gathering fresh data no longer revealed new theoretical insights or new properties of the core categories (Charmaz, 2014). During sampling, coding, and analyses, we discovered that some topics of conversation could apparently be included and others seemed to be excluded during the counseling. The data analysis were increasingly focused on disclosing how the HCPs maintained a distinction between possible and impossible topics and why the distinction of topics was necessary to maintain. Among other things, “looking for lifestyle markers,” “avoiding the impossible,” and “ignoring the insecure topics” were constructed as initial categories in the focused coding.

In Table 1, we have illustrated parts of the analysis process. To the left, we show selected examples of quotes from the HCPs; subsequently, there are examples of initial coding, focused coding, the emergent main category, the related subcategories, and the main concern of the HCPs during interaction with patients. The table is not to be regarded as an exhaustive analysis overview but rather as a limited illustration of the coding and analysis processes.

Table 1.

Coding and Data Analyses.

| Theoretical Coding |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excerpt | Initial Coding | Focused Coding | Subcategory | Main Category | Main Concern |

| 1. So all the policies implemented today . . . It’s the actions that accommodate those who already can . . . it’s really really hard to meet the fragile and vulnerable patients who cannot achieve the expected lifestyle changes . . . and listen to what they want and what they can accomplish . . . “How can I really support you in this . . . what is it you want to achieve? If you want to see your son getting married, then it’s probably now you need to make the changes and do things in another way, right?” (HCP) 2. Some of the patients have a psychological problem that sometimes renders irrelevant what we are saying to them . . . (HCP) 3. I mean, that’s the way it is . . . Some have more resources than others . . . That’s the way it will always be . . . We can’t give knowledge to people who are not able to take it in . . . (HCP) 4. We are not grasping the story . . . We think we are . . . but we are not, because we are treating them all the same . . . (HCP) 5. . . . You may also worry about what you are digging into . . . because you cannot manage to put a lid on the problems before ending the interaction (HCP) |

Powerlessness Obligations Lack of strategies Hopelessness Resignation Impact focusing Lack of skills Uncertainty Frustration |

Looking for lifestyle markers Controlling patient information Maintaining mind and body separately Avoiding the impossible Ignoring the insecure Avoiding failure and sorrow |

Maintaining the sick lungs as the main task Avoiding the existential suffering in patients Avoiding the non-alterable |

Maintaining a distinction between possible and impossible topics of conversation | Striving to manage contradictory expectations to the content of counseling |

Note. HCP = health care professional.

Validity

The criteria to validate the findings followed Kathy Charmaz’s credibility, originality, resonance, and usefulness (Charmaz, 2006, 2011). A clear and rigorous working process, as described in the data analysis, assured credibility. Originality can be identified; thus, we explored an underexposed area where knowledge is limited concerning the patterns of behavior in HCPs during counseling of the patients in the ORMC. To achieve resonance, the study must be relevant to the participants. Indeed, the patients and the HCPs showed great interest in the study. The HCPs, in particular, expressed the importance of developing better understanding and visibility of daily efforts to meet the needs of the patients in the ORMC. In addition, we ensured the relevance of the emergent theory through ongoing discussions of findings with patients, HCPs, and research fellows. The usefulness and applicability of our study may be difficult to estimate at this time. The study predominantly offers explanations and understandings of the behavior of the HCPs during interactions. Subsequent studies should adjust the results to further development of the practice that it describes. The health care system seems to have undergone many changes in Western countries. The barriers against the HCPs and the opportunities they had to provide help and support the patients may change over time. Consequently, the theory may be adapted and revised to maintain relevance for those involved in counseling in the ORMC.

This study is based on extensive data and generated from multiple data sources: field observations, individual interviews, a focus group interview, and discussions with fellow researchers and participants. The findings are then discussed and compared with other clinical studies. The nature of the simultaneous data collections, samplings, coding, and analyses secured, to a certain extent, that the findings were not based on random interpretations. Moreover, peers have been presented with the findings to discuss the developed theory further. Several participants contributed with insights and points that have been of great importance to the analysis process. One limitation of this study may be the lack of distinguishing between the behaviors of the nurses and the doctors. Although we found an overall congruence in the statements, further exploration of the differences may have contributed with new knowledge about the nurses’ and doctors’ specific differences in attitudes to patients. The common feature of behavior in HCPs is maintained; therefore, the intention of this study is to explore the convergence of attitudes and actions rather than the differences in the HCPs regarding counseling of the patients in the ORMC.

Ethical Consideration

All interviews and field observations have been carried out with respect for the HCPs’ and patients’ experiences and actions. The project was carried out in accordance with International Council of Nurses (ICN; 2012)’s code of ethics for nursing research and approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (j.nr. 2011-41-6670). The National Committee on Health Research Ethics was presented with the project description and found a formal evaluation to be unnecessary (pr.nr. H-4-2012-FSP 95). Oral and written information about the study was given to the participants including information on anonymity, informed consent, confidentiality, and the right to end participation at any time without stating a reason. All personal identifiers have been removed or disguised, so that the participants are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details in this article.

Findings: Maintaining a Distinction Between Possible and Impossible Topics of Conversation

Striving to manage contradictory expectations to the content of counseling was found to be a main concern in many HCPs during interactions with patients. The HCPs were under a lot of pressure during interactions to collect the mandatory information from patients, perform the necessary examinations, and respond to questions from the patients. Counseling and treatment were tightly structured according to topics that involved mandatory discussion and were documented within the restricted time frame determined for each patient. The HCPs, first and foremost, prioritized the performance of the mandatory tasks, which were to be documented in the patient journal and hospital records. Conversely, we found a need in patients to share emotions of existential suffering regarding illness and its implications for everyday life. The expectation for counseling caused problems and difficulties during interactions as the patients’ and HCPs’ expectations regarding the topics mostly conflicted. The HCPs had practical and theoretical knowledge of the ways that patients’ everyday lives could appear to be affected by existential suffering. At the same time, they were mostly aware of the patients’ desire to share these emotions. The HCPs could assume that patients demanded good advice and answers regarding their suffering and powerlessness, which the data did not confirm. Rather, the patients were striving to achieve empathy for and responsiveness to their efforts to find ways to adapt to illness and existential suffering and cope with death and dying.

Maintaining a Distinction Between Possible and Impossible Topics of Conversation

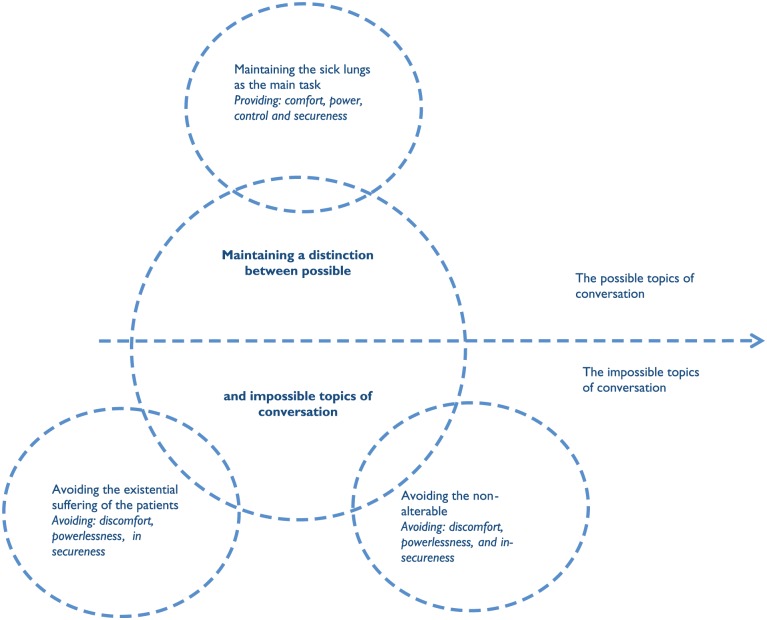

The main category, maintaining a distinction between possible and impossible topics of conversation, conceptualizes how the HCP managed the contradictory expectations of the content by maintaining a distinction between possible and impossible topics of conversation in the ORMC. We found three subcategories explaining the way in which impossible and possible topics were maintained and divided during conversation: (a) an effort to maintain the diseased lungs as the main task in counseling, (b) navigating interactions to avoid revealing strong emotions of suffering in patients, and (c) avoiding the appearance of non-alterable life circumstances of the patients. The possible topics were related to the diseased body whereas the impossible topics concerned existential suffering of the patients and their non-alterable life circumstances. Figure 1 explains the theory of maintaining a distinction between possible and impossible topics of conversation. The horizontal arrow straight through the figure shows the dividing line between the possible and impossible topics of conversation. Meanwhile, the main circle shows the main category of the theory. The three minor circles show the patterns of behavior of the HCPs in obtaining a distinction between possible and impossible topics of conversation.

Figure 1.

Maintaining a distinction between possible and impossible topics of conversation.

Main Category: Maintaining a Distinction Between Possible and Impossible Topics of Conversation

The distinction between possible and impossible topics provided a mode of control, comfort, power, and security in HCPs during counseling. The possible topics of conversation referred to the patient’s lungs, monitoring of the CRD, control of the body and its current abilities, and the physical consequences of the patient’s lifestyle. These topics included drug regulation, lung function tests, body mass index (BMI), function level and exercise, and diet and smoking cessation counseling. The HCPs considered these topics to be natural, self-evident, and important in the interaction and believed that they would contribute positively to the patient’s situation as long as the patient lived in accordance with their counseling. The HCPs also regarded these topics to be their main tasks and the essence of the interaction with the patients. They often argued of their importance, pointing to the frames of the mandatory tasks to be performed, the possibilities they could identify, the need to guide patients in lifestyle changes, and the frames in which they could offer only specific disease-related counseling.

The impossible topics included the patient’s adjacent chronic diseases, emotions of suffering, powerlessness, death and dying, conflicting lifestyle behavior, or lifestyle being perceived as non-alterable. The patients often urged the HCPs to recognize their feelings of suffering, made efforts to find alternative methods of overcoming disease, and expressed a desire to achieve hope in mostly difficult and complex life situations. One patient stated his feeling thusly:

I feel that I was put out of the game in the ORMC. “You are on your own with those psychological issues, and we can give you another prescription. You can get some other pills, right! Jesus. Instead of, “What can I do without the pills?” But nothing else is done. (patient [PT])

The HCPs often addressed the impossibility of addressing such topics due to lack of time, lack of competency, and the fact that these topics were out of the scope for the ORMC’s assistance and counseling. One professional accordingly stated, “To what extent do we need to agree to these stories? To what extent are we allowed to demolish the story? I need to tell the patient that this is what I can offer, so . . . ” (Registered Nurse [RN]). Through the distinction of possible and impossible topics, the content of existential suffering and perceived non-alterable life circumstances remained non-relevant, and the diseased lungs were perceived as natural and obvious topics for counseling by the HCPs.

The patterns of behavior among HCPs avoided revealing strong emotions of suffering in patients and provided comfort and control of topics with the HCPs during interaction. The HCPs seemed to balance the expectation of emotional response from patients and at the same time made an effort to avoid powerlessness and discomfort when conversation topics were challenged. As a result, the patients’ attempts to express emotional suffering or discuss non-alterable life conditions caused patterns of behavior in the HCPs as we describe in the following sections.

Maintaining sick lungs as the main task

Avoiding topics of conversation, which was not on the mandatory agenda for counseling, set forth sick lungs as the main task during counseling. Maintenance of sick lungs was achieved by focusing on lifestyle markers, disease markers, and medicinal intervention and testing of the patient’s physical condition. The tasks were mainly oriented and directed toward identifying and establishing possible solutions to patients’ physical and disease-related problems. Thus, smoking cessation, exercise, diet, weight loss or weight gain, and control of drug compliance were perceived as central issues in counseling. The HCPs welcomed the times when patients listened to instructions and successfully experienced guidance and when patients received advice or any medication and adjustment was affected. The overall pattern of regarding sick lungs as the main task during counseling was expressed in several ways by the HCPs:

We’ve become doctors because we fundamentally want to save lives . . . That’s our drive . . . Patients will die or can no longer be treated . . . It’s a side effect of this job . . . and we have to accept it and go along with it . . . and it’s always really sad . . . but basically we want to cure and heal . . . That is what we are trained for . . . That is why we became doctors in the first place. (Medical Doctor [MD])

Regardless of the patient’s disease severity, the same content of counseling was performed. Patients whom the HCPs considered severely affected by CRD were guided in lifestyle changes, treatment, and rehabilitation to the same extent as patients considered less severely affected by CRD. Palliative care and topics on how to cope with death and dying were not discussed even though many patients were perceived as having CRD in a terminal stage. The conversation caused frustration among the HCPs when patients did not understand or shared the same assumption about the content of the conversation. At the same time, the HCPs had difficulty understanding patients’ preoccupation with issues they experienced that were beyond their reach for giving direction. In the words of one health care provider,

I see many patients who have no idea of why they are coming, and they are basically indifferent too; they just come here, but basically are not interested in getting any better, right? I often hear them out at the front disk when asked, “Why are you here today?” “I do not know,” they say. They don’t have a clue . . . They are totally blank as to why they come here . . . (RN)

Avoiding the existential suffering in patients

The existential suffering of the patients appeared to generate discomfort, powerlessness, and frustration in the HCPs as well as they rarely knew how to handle or alleviate these emotions. Listening to patients’ existential suffering was a difficult task for many HCPs, and when the patients and the HCPs experienced conflicting expectations regarding the conversation topics, this situation mostly caused frustration and powerlessness for both parties. The HCPs managed the appearance of patients’ existential suffering by avoiding, ignoring, or rejecting any attempt to initiate these topics when considered to be unsolvable or if a reply involved risk when they did not have a solution to patients’ problems:

If we are to listen . . . and take what they are saying seriously, then . . . well, we have only three minutes to discuss it . . . So, the question is, what we can do about it, and what we are digging into? Then there is this, “What did you say? . . . No, I did not hear what you just said,” because . . . to move on, right . . . and I understand that as a patient you would think that “She is not listening to a bloody thing I’m saying to her.” (RN)

The HCPs explained their lack of responsiveness to patients’ suffering due to the topic contents being outside the scope of their standards and guidelines, lack of time, lack of competency to discuss the problems, or having the risk of harming the patients due to a lack of knowledge and skills. Hence, one staff member said, “But we cannot give counseling to just one patient per day . . . and we are not psychologists, are we now? We are not trained to do this? This is why we are being careful, right?” (RN).

The HCPs became frustrated when they knew that patients expected them to listen to and recognize their existential suffering. They could express concerns but did not want to inflict further suffering by allowing the conversation to move toward existential problems about which they felt insecure and without the necessary competencies to give advice:

Sometimes you hear what they are saying, right? And you know what you feel like answering, right? . . . But you have no right to show a patient that you are interested in him or her and “Tell me your story” and then . . . “OK, now I don’t have any more time to listen to you anyway,” right? . . . If you want to hear the story . . . you need to listen to it . . . otherwise I actually think that you are doing more harm than good. (RN)

Topics as existence at stake such as suffering, death, and dying, seemed to trigger powerlessness and discomfort in HCPs. On the other side, the patients had a need to express and discuss these matters:

I can’t fight the way I used to . . . So I sort out, I give up, because I don’t have the energy . . . They don’t understand how hard it is and how they could help a little more with . . . well, asking and be more like . . . caring, actively discussing and a little more like . . . interested instead of acting only specialized clinical. (PT)

Although many patients had an awareness regarding their need to share emotions about suffering, death, and dying, the HCPs dismissed or rejected these topics and at the same time mostly were aware of their deselecting of these topics:

Sometimes we probably evade a little bit . . . We know what they really want to talk about . . . but we know very well that we have nothing to offer or nothing we can do about it . . . So you feel powerless . . . So you might well realize that they need some help, right? . . . For some psychological thing . . . but where do we send them? If they are lucky, they can have five hours with a psychologist, and it does not help very well, right? (RN)

Many patients had come to terms with the progression of CRD and the limited life span caused by severe CRD.

A terminally ill patient explained during the interaction in the ORMC how the disease was developing rapidly and concluded by saying, “I know how this ends.” The nurse nodded and replied, “Let’s see what you can manage today during the lung function test.”

During the following interview a few days later the patient explains his sadness regarding his impending death:

Patient (PT): I’ll have to take it as it comes . . . The most annoying and sad part is that there are many things that I would have liked to see and join . . . in the long term . . . and how they develop . . . and I do very well know that I won’t . . . I don’t have that opportunity . . . so . . .

Interviewer: Have anyone talked with you about your thoughts?

PT: No, . . . no one.

To many patients, the expectation of a soon-coming death was found to be in contrast to the absence of death and dying as a subject during counseling. Death and dying were not perceived as a task within the HCPs opportunities to engage during conversation in the ORMC. Improvement and rehabilitation appeared to be regarded as the main task regardless of the severity of the patient’s disease. The effort to help, heal, and offer solutions for the physical problems of the patients was found to be a consistent approach in the HCPs:

So if you are wasting your time becoming a priest or psychologist during the conversation . . . I cannot achieve what I need . . . My focus is the sick body. So I do think that you need to be the doctor of your patients; nobody else is. That’s your duty. Then others may take care of the patient’s psychological problems . . . Actually, I do not think that this is what I should do. (MD)

The patient’s existential suffering was considered to be non-relevant to the specialized ORMC and was perceived as a topic they neither could nor should include in counseling.

Avoiding the non-alterable

The HCPs expressed concerns regarding patients they perceived as having a lack of motivation to make lifestyle changes, were unprepared for counseling, or refused to take the counseling into account. The HCPs were aware that some patients might not benefit from the conversation. In the words of one,

It is also important that the patient is really interested in coming to talk to us . . . There is a difference if you come here because you have to or because you want to feel better . . . and some patients do not seem to be interested in feeling better. (RN)

When the illness- or lifestyle-related counseling did not help the patient or was not found to be consistent with the patient’s values or beliefs, it could cause frustration for the HCPs: “We really want to solve their problems, right? When the patients tell us that they are feeling bad . . . we would like to be able to say, just do this and that, right?” (HCP). Apparently, the HCPs lacked strategies for counseling patients who did not want to adapt to counseling or refused to discuss lifestyle-related suggestions. The HCPs problematized the difficulties in reaching these patients and perceived that they might not receive adequate assistance in a complex life situation. At the same time, the HCPs felt powerless and bereft of any self-perceived possibilities of helping. During an interview, a patient explained his opposition to lifestyle changes and his frustration with the guidance in the outpatient clinic as follows:

Well, I do not want them to bang me in the head with those damn cigarettes . . . They’ve been telling me the same thing for 15 years, and it sure as hell hasn’t changed anything . . . so why do they think that telling me one more time would be of any difference? It becomes a torment that you have to hear the same thing over and over . . . well, I know very well . . . Ever since they found the disease, they have told me that I should stop smoking . . . but it’s all I have left of joy . . . And it’s not for them to decide . . . In other words, it’s annoying . . . and how stupid do they think I am . . . really? They have been telling me the same speech over and over. (PT)

The HCPs also distinguished between patients whom they thought could possibly be helped to help, and conversely, patients whom they thought were impossible to help at the time. Patients who perceivably could be helped could implement lifestyle changes, adhere to medication changes, and appeared receptive to advice and instructions. But patients who were perceived as impossible to help did not take the prescribed medicine or would not accept nor perform lifestyle changes as recommended by the HCPs. These patients were regarded as having an inappropriate lifestyle, bad habits, and low disease control. One HCP stated accordingly,

But we often see that they are not going to do anything about it . . . I mean, they come here for a diagnosis, and we prescribe medicine, and then they do not want to take it, right? It is such a shame . . . I mean, you think . . . why did you come here, then, right? But other things are more important to them, right? Other things play a part. (RN)

The HCPs expressed self-perceived powerlessness in relation to topics that could be important to patients such as continuing smoking, keeping pets while having asthma, or continuing an insufficient diet. Mostly, the HCPs referred to patients’ free choice of options to either follow the recommendations or continue an unhealthy lifestyle. The HCPs recognized that the life conditions of the patients differed significantly, but ultimately, they perceived patients as being self-responsible for the lifestyle choice and strategies in health and illness. Adaptable patients were given positive affirmations and recognition for executing new exercise habits, altering diet, or quitting smoking. Patients who were not able or willing to fulfill lifestyle changes would mostly be met with disapproval or a resigned approach in which the HCPs referred to the patients’ free choice to accept the counseling:

“Well, it’s for you to decide” or “Ultimately, it’s entirely up to you.”

The HCPs rarely explored the patient’s reason for rejecting counseling or provided shared compromises for lifestyle changes. Patients who were not inclined to accept the counseling frustrated the HCPs, who perceived them as being difficult or impossible to help and would express doubts about the usefulness of the patient’s ambulatory course:

Well, we can only say that if you do this and that, your chances are better . . . and it’s their own choice to do what is best or worst for them . . . Basically, it’s up to them . . . What is the most important to you? . . . What would satisfy you? (MD)

The HCPs could maintain guidance they considered to be hopeless presuming these patients either would or could benefit from their advice in everyday life. The maintenance of a consistent and uniform counseling regimen was conducted in hoping for the patient’s impending readiness to make lifestyle changes or hoping that a colleague could reach the patient provided that the proposed lifestyle changes would be performed. The HCPs pointed to socioeconomic factors, educational level, and network resources as determining the possibilities to patients’ strategies in living with CRD. Poor living conditions led to frustration and powerlessness in the HCPs’ minds when they were not able to help patients who were considered to be living in non-accordance with their counseling:

Well, we do meet people who have been self-destructive throughout their entire adult life, and then we recommend that they change their conduct . . . That’s simply not useful to them . . . Their entire lives are based on self-destructive conduct . . . What we say does not fit into their life stories . . . They can’t make any use of it . . . but that’s the way it is, right? (RN)

The complex situation of many patients’ and the HCPs’ powerlessness in relation to self-perceived lack of skills in guiding and supporting patients triggered a reluctance about bringing these topics into counseling. Accordingly, the HCPs maintained the well-known frame of topics regarding disease control and lifestyle changes by which they could provide clear answers, interventions, and counseling.

Discussion

The original idea of this study was to explore the patterns of behavior in HCPs during interactions with patients in the ORMC. The emergent theory of this study explains how the contradictory expectation regarding the content of the conversation caused discomfort in patients and HCPs during interactions in the ORMC. The HCPs’ interpretation in the ORMC as a place for primary cure and treatment was maintained through a systematic guidance focusing on medication, monitoring, and counseling in lifestyle changes. The content of the counseling was not found to differ despite the CRD’s severity in the patients. The patients could perceive the disease as being beyond the reach of HCPs to treat and hoped for counseling as an opportunity to share emotions of fear, doubts, and powerlessness.

We found a distance between the HCPs and patients regarding the needs of the patients and a gap in the HCPs’ beliefs of patients’ insight into their illness and hope for the future. In addition, both patients and HCPs felt powerless regarding the life conditions and lifestyle choices of many patients. This circumstance mostly caused difficulties for the HCPs in bringing change and intervention. These findings support other studies suggesting an effort to relieve the suffering and to support the patients’ efforts to live their best possible everyday life (Bisgaard, Backer, Lange, Lykkegaard, & Søgaard, 2013; Fiscella & Epstein, 2009). The findings also suggest a lack of experience in being able to accommodate, tolerate, and relate to the suffering of the patients during counseling (Frank, 1995; Wong et al., 2014). Likewise, HCPs used the time frames and the mandatory conversation subjects as an opportunity to avoid the discomfort of existential conversation topics.

However, before discussing the implications of the findings for clinical practice, it is important to reiterate this point: although the HCPs may seem to avoid giving attention to the existential needs of the patients, several studies suggest explanations for the findings. Many studies point to phenomena outside the HCPs’ control as essential to their patterns of behavior. Moreover, studies point to exhaustion in HCPs as being caused by volume of duties, numerous changes in the working structure, the implementation of new or changed administrative tasks, new clinical guidelines, and an increased demand for documentation (Michaelsen, 2012). Another factor includes increased production requirements in terms of a higher number of patient contacts in less time (Fiscella & Epstein, 2009). In a study of Bakker et al., researchers found that doctors perceived “demanding” patients to be a contributing cause of burnout. They found, consistently with other studies, that the lack of reciprocity in the interaction seemed to be essential to the development of emotional burnout among doctors (Bakker et al., 2000; Potter, 1983). The imbalance was initiated by patients’ skeptical or critical approaches, lack of gratitude, or non-recognition of the HCP’s efforts to help them (Bakker et al., 2000). In addition, studies suggest that patients who do not agree with good advice, appear demanding or dissatisfied, or appear to have a dismissive attitude regarding good advice are considered to be exhausting, reduce HCPs’ job satisfaction, and may create emotional distance between HCPs and themselves (Michaelsen, 2012). Furthermore, studies suggest that HCPs’ emotional burnout may limit their empathy and result in generating a cynical attitude, leading to the depersonalization of patients and a reduced sense of competence among HCPs (Bjørg, 2008; Michaelsen, 2012). It has been suggested that the reason may be found thusly: HCPs are trying to maintain an emotional distance from patients as a way to deal with their own emotional exhaustion and restore the self-perceived imbalance in the interaction (Bakker et al., 2000; Conway, 2000; Potter, 1983).

Listening to the voices of the patients suffering may be a difficult task for many HCPs. The patients’ voices can easily be ignored because they may be mixed in message, wavering, or incoherent (Barry, Bradley, Britten, Stevenson, & Barber, 2000; Frank, 1995). This situation puts demands on HCPs to meet the individual and complex expectations of patients, and several researchers point to a certain inertia in the readjustment of health services in a society where many patients are critical toward experts and where the demands on HCPs are constantly changing (Bury, 2004; Thorne, 2006). In conclusion, several studies indicate a strong tradition among HCPs of distinguishing between patients’ existential problems and biological disease-related problems, which may cause conflicting perspectives during interactions (Abrosimov et al., 2005; Wong et al., 2014). We have pointed out several possible explanations for HCPs’ lack of responsiveness to patients’ emotions and complex lifestyle factors during interactions. We have, to some extent, identified the same patterns of emotional exhaustion in HCPs. Unlike many other studies, we found pronounced and observed concern, frustration, and powerlessness in HCPs regarding a self-perceived limited ability to offer existential support and care to patients during interactions. This study provides new knowledge regarding how the HCPs maintain control of the interaction to retain treatment and focus on the diseased lungs as the main task during counseling. Our findings point out that knowing the progressive nature of CRD may not give rise to targeted attention to palliative conversations in the ORMC.

Conclusion

The distinction between possible and impossible topics in counseling was an overall pattern of behavior in the HCPs to manage conflicting expectations regarding the contents of interaction. Nonetheless, the distinction of possible and impossible topics caused frustration, distance, and discomfort in both patients and HCPs. The discomfort may partly have been caused by the HCPs considering the ORMC as a place for treatment rather than palliative care. Regardless of the patients’ disease severity, life circumstances, and emotional state, the conversation was retained as a place to control the disease, lifestyle changes, and treatment. The HCPs’ experiences of what the patients could be offered, and on the contrary, the patients’ experiences of the possibility of dying, lifestyle choices, and living conditions generated a distance and a difficulty that created further suffering in the patients but likewise a discomfort and frustration among the HCPs.

Implications for Practice and Research

The findings of this study suggest a need for further exploration as to how care and treatment can be differentiated to meet the needs of patients, concerning the extent of the existential suffering in patients, the difference in life circumstances, and the ability to promote lifestyle changes in patients. In addition, our findings point to a lack of palliative counseling in the ORMC regardless of the patients’ disease severity. We point to a need to extend the goals of ORMC counseling to include palliative counseling. This is due to the significance of many ORMCs regarding counseling and treatment of many patients suffering from severe CRD. In line with other studies, we assume that the experiences of the patients hold far greater potential than that of merely informing HCPs regarding mandatory data required for the patients’ records (Bailey, 2001; Boyles, Bailey, & Mossey, 2013; Charon, 2001; Mattingly, 2005).

Listening to the patients’ experiences may provide hope and faith among patients and may be an effective means of challenging HCPs’ understanding of the purpose of counseling. This is because listening may reveal the patients’ perspectives regarding what healing can be when there is no faith in cure from the disease (Mattingly, 2005). The experiences of the patients can possibly, when recognized, create a different kind of conversation where the distance in perspectives can be reduced and the aim of meeting patient needs can be accomplished. Perhaps even greater job satisfaction may also be possible among HCPs. We suggest that the HCPs include the already available time frame to conduct an open dialogue and prioritize the tasks and topics that are the most important to the patients. This procedure can then establish a counseling method based on the patients’ situation and concerns regarding life and illness at the present time.

We further suggest a need for education to advance insight and knowledge among HCPs regarding patient needs and the ethical responsibility, benefits, and opportunities for palliative care in the ORMC. At the same time, future studies should explore interactions in the ORMC to develop skills and strengthen a patient-centered approach in counseling. This protocol would include the recognition of patients’ experiences to strengthen the shared understanding of patient concerns during counseling in the ORMC.

Author Biographies

Lone Birgitte Skov Jensen, RN, MNSc, is a PhD student at Department of Education, University of Aarhus, and assistant professor at the Nursing School UCC Hillerød, the Regional Capital, Denmark.

Kristian Larsen, PhD, is a professor of Department of Education, Learning and Philosophy, University of Aalborg, Denmark.

Hanne Konradsen, RN, MNSc, PhD, is an associate professor at the Department of Neurobiologi, Care Sciences and Society, Karolinska Institute, Sweden.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abrosimov V., Khaled N. A., Maesano I. A., Bateman E., Kheder A. B., Bousquet J., Viegi G. (2005). Prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases at country level: Towards a global alliance against chronic respiratory diseases. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/respiratory/publications/crd_country_level/en/

- Anderson W. G., Kools S., Lyndon A. (2013). Dancing around death: Hospitalist-patient communication about serious illness. Qualitative Health Research, 23, 3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong T., Krzyzanowski M., Mafat D., Ottmani S. E., Pruess-Ustun A., Rehfuess E., Yusuf O. (2007). Global surveillance, prevention and control of chronic respiratory disease. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey P. H. (2001). Death stories: Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Qualitative Health Research, 11, 322–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajwah S., Higginson I. J., Ross J. R., Wells A. U., Birring A. U., Riley J., HKoffman J. (2013). The palliative care needs for fibrotic interstitial lung disease: A qualitative study of patients, informal caregivers and health professionals. Palliative Medicine, 27, 869–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A., Schaufeli W., Sixma H., Dierendonck D. (2000). Patient demands, lack of reciprocity, and burnout: A five-year longitudinal study among general practitioners. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 425–441. [Google Scholar]

- Barry C. A., Bradley C. P., Britten N., Stevenson F., Barber N. (2000). Patients’ unvoiced agendas in general practice consultations: Qualitative study. British Medical Journal, 320, 1246–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgaard H., Backer V., Lange P., Lykkegaard J., Søgaard J. (2013). National report regarding the quality of care for COPD in Denmark. Retrieved from https://www.lunge.dk/sites/default/files/argumenter_for_en_national_lungeplan_19_april_2013.pdf

- Bjørg C. (2008). Good work—How it is recognized by the nurse? Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17, 1645–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blands J., Bælum L. (2007). KOL—KRONISK OBSTRUKTIV LUNGESYGDOM Anbefalinger for tidlig opsporing, opfølgning, behandling og rehabilitering [COPD—Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease recommendations for early detection, monitoring, treatment and rehabilitation]. Copenhagen, Denmark: Retrieved from http://sundhedsstyrelsen.dk/publ/Publ2007/CFF/KOL/KOLanbefalinger.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Pespective and method. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borge C., Wahl A., Moum T. (2010). Association of breathlessness with multiple symptoms in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66, 2688–2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourbeau J., Nault D.-T. (2004). Self-management and behaviour modification in COPD. Patient Education & Counseling, 52, 271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyles C. M., Bailey P. H., Mossey S. (2013). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as disability: Dilemma stories. Qualitative Health Research, 21, 187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury M. (2004). Researching patient–professional interactions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 9(Suppl. 1), 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz C. (1990). “Discovering” chronic illness: Using grounded theory. Social Science & Medicine, 30, 1161–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz C. (2004). Premises, principles, and practices in qualitative research: Revisiting the foundations. Qualitative Health Research, 14, 976–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz C. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz C. (2011). Grounded theory methods in social justice research. In Denzin N. L. Y. (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (Vol. 4, pp. 359–380). London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz C. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.) (Seaman J., Ed.). Dorchester, UK: Dorset Press. [Google Scholar]

- Charon R. (2001). Narrative medicine: A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. Journal of the American Medical Association, 286, 1897–1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.-H., Chen M.-L., Lee S., Cho H.-Y., Weng L.-C. (2008). Self-management behaviours for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 64, 595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicutto L., Brooks D., Henderson K. (2004). Self-care issues from the perspective of individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Patient Education & Counseling, 55, 168–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway P. (2000, May 15-17). Characteristics or traits of patients which may result in their being considered as “difficult” by nurses. Paper presented at the Qualitative evidence-based practice Conference, Coventry University, Coventry, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz A., Mantzouranis E., Matricardi P., Minelli E., Aït-Khaled N., Bateman E., . . . Zhong N. (2007). Global surveillance, prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Disler R. T., Green A., Luckett T., Newton P. J., Inglis S., Currow D. C., Davidson P. M. (2014). Experience of advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Metasynthesis of qualitative research. Journal of Pain Symptom Manage, 48, 1182–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubbin L. A., Chang J. S., Shim J. K. (2013). Cultural health capital and the interactional dynamics of patient-centered care. Social Science & Medicine, 93, 113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ek K., Sahlberg-Blom E., Andershed B., Ternestedt B.-M. (2011). Struggling to retain living space: Patients’ stories about living with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67, 1480–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R. M., Fiscella K., Lesser C. S., Stange K. C. (2010). Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Affairs, 29, 1489–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K., Epstein R. (2009). So much to do, so little time: Care for the socially disadvantaged and the 15-minute visit. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168, 1843–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank A. W. (1995). The wounded storyteller: Body illness, and ethics. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner C., Gott M., Small N., Payne S., Seamark D., Barnes S., . . . Ruse C. (2010). Living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Patients concern regarding death and dying. Palliative Medicine, 23, 691–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini M., DeJean D., Simeonov D., Smith A. (2012). Experiences of living and dying with COPD: A systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative empirical literature. Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series, 12, 1–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giot C., Maronati M., Becattelli I., Schoenheit G. (2013). Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: An EU Patient Perspective Survey. Current Respiratory Medicine Reviews, 9, 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD - 2016 (GOLD). (2015, December). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Retrieved from http://www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management.html [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gysels M., Higginson I. J. (2010). The experience of breathlessness: The social course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Pain Symptom Manage, 39, 555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Council of Nurses. (2012). The ICN code of ethics for nurses. Geneva, Switzerland: Retrieved from http://www.icn.ch/who-we-are/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/ [Google Scholar]

- Karakurt P., Ünsal A. (2013). Fatigue, anxiety and depression levels, activities of daily living of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 19, 221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayahan B., Karapolat H., Atyntoprak E., Atasever A. (2006). Psychological outcomes of an outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation program in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiratory Medicine, 100, 1050–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvangarsnes M., Torheim H., Hole T., Öhlund L. S. (2013). Narratives of breathlessness in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22, 3062–3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange P. (2009). Quality of COPD care in hospital outpatient clinics in Denmark: The KOLIBRI study. Respiratory Medicine, 103, 1657–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen K., Cutchin M. P., Harsløf I. (2013). Health capital: New health and personal investment in the body in the context of changing Nordic welfare states. In Harsløf I., Ulmestig R. (Eds.), Changing social risk and social policy responses in the Nordic welfare states (pp. 165-188). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lawn S., Delany T., Sweet L., Battersby M., Skinner T. C. (2014). Control in chronic condition self-care management: How it occurs in the health worker–client relationship and implications for client empowerment. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70, 383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist G., Hallberg L. (2010). “Feelings of guilt due to Self-inflicted Disease”: A grounded theory of suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Journal of Health Psychology, 15, 456–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucius-Hoene G., Thiele U., Breuning M., Haug S. (2012). Doctors’ voices in patients’ narratives: Coping with emotions in storytelling. Chronic Illness, 8(3), 161–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly C. (2005). The narrative turn in contemporary medical anthropology. Journal of Research in Health and Society, 9, 427–429. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelsen J. J. (2012). Emotional distance to so-called difficult patients. Caring Science, 26, 90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parshall M., Schwartzstein R., Adams L., Banzett R., Manning H., Bourbeau J., . . . O’Donnell D. (2012). An official American thoracic society statement: Update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 185, 435–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter B. (1983). Job burnout and the helping professional. Clinical Gerontologist, 2, 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Rabe K., Hurd S., Anzueto A., Barnes P., Buist S., Calverley P., . . . Zielinski J. (2007). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 176, 532–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour J. M., Moore L., Jolley C. J., Ward K., Creasey J., Steier J. S., Moxham J. (2010). Outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation following acute exacerbations of COPD. Thorax, 65, 423–428. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.124164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim J. M. (2010). Cultural health capital: A theoretical approach to understanding health care interactions and the dynamics of unequal treatment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. (2006). Patient-provider communication in chronic illness: A health promotion window of opportunity. Family & Community Health, 29(Suppl. 1), 4S–18S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S. S. L., Abdullah N., Abdulla A., Liew S.-M., Ching S.-M., Khoo E.-M., . . . Chia Y.-C. (2014). Unmet needs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): A qualitative study on patients and doctors. BMC Family Practice, 15, Article 67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2002). WHO strategy for prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/respiratory/publications/crd_strategy/en/