Abstract

Despite literature highlighting the relevance of negative and positive emotions to risky behaviors, little research has examined the emotion-dependent context of risky behaviors. This study sought to develop and validate a comprehensive measure of the frequency and emotion-dependent context of distinct clinically-relevant risky behaviors (the Risky Behavior Questionnaire [RBQ]), as well as to examine the unique relations of the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales (which assess the general tendency to engage in risky behaviors in the context of negative versus positive emotions, respectively) to specific risky behaviors. Participants were 176 patients in a residential substance use disorder treatment facility (M age = 34.18; 65.3% White, 53.4% female). Results provided support for the construct and incremental validity (relative to extant measures of related constructs) of the RBQ Scales, as well as the differential relevance of RBQ Negative and Positive Scales to specific risky behaviors.

Keywords: risky behaviors, substance use, risky sexual behavior, criminal behavior, deliberate self-harm, negative emotions, positive emotions

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are widespread in the United States, with recent epidemiological data indicating lifetime and past-year prevalence rate for DSM-5 alcohol and drug use disorders of 13.9% and 29.1% and 3.9% and 9.9%, respectively (Grant et al., 2015, 2016). These high rates are particularly troubling given the number of deleterious outcomes associated with SUDs (Cartwright, 1999), including heightened engagement in risky, self-destructive, and health-compromising behaviors (e.g., risky sex, self-harm, criminal behavior; D’Amico, Edelen, Miles, & Morral, 2008; Gratz & Tull, 2010; Lejuez, Simmons, Aklin, Daughters, & Dvir, 2004). Given evidence that such behaviors may exacerbate the harmful outcomes associated with SUDs (e.g., Patkar et al., 2011), research focused on elucidating the factors that contribute to these behaviors in SUD patients has great public health significance.

In particular, in order to improve treatments for risky behaviors among SUD patients, research is needed to identify the contexts in which these behaviors are more likely to occur. Recent literature highlights the key role of negative and positive emotions in the development and maintenance of risky behaviors. Specifically, theory and research suggest that risky behaviors may be emotion-dependent (e.g., Cyders & Smith, 2008), or more likely to occur in the context of intense positive or negative emotions. For example, intense negative and positive emotions may undermine advantageous decision making (Bechara, 2004; Driesbach, 2006), resulting in less discriminative use of information (Forgas & Bower, 1987) and greater distractibility (Dreisbach & Goschke, 2004) that may increase decision-making focused on short-versus long-term goals (Slovic, Finucane, Peters, & MacGregor, 2004). Alternatively, the down-regulation of intense positive and negative emotions is an effortful, and not necessarily immediately rewarding, process. According to Inzlicht and Schmeichel (2012), as the need for regulation persists, individuals may begin to experience a shift in motivation from the regulation of emotion towards the acquisition of more immediately rewarding and gratifying experiences. This shift in motivation coincides with an increased allocation of attention towards cues that signal more immediate gratification and reward (vs. the need for self-regulation), increasing the likelihood of disinhibited or risky behaviors (Inzlicht & Schmeichel, 2012).

Recent research also provides support for the emotion-dependent nature of risky behaviors. For example, negative and positive urgency, or the tendency to engage in rash action in the context of intense negative and positive emotions, respectively, have been found to be more strongly related to risky behaviors than other dimensions of impulsivity (Berg, Latzman, Bliwise, & Lilienfeld, 2015; Coskunpinar, Dir, & Cyders, 2013; Cyders & Smith, 2008). Likewise, the dimension of emotion regulation that overlaps with negative urgency (i.e., the Impulse subscale of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) has been found to be uniquely related to alcohol consumption (Dvorak, Sargent, Kilwein, Stevenson, Kuvaas, & Williams, 2014), physical aggression (Donahue, Goranson, McClure, & Van Male, 2014) and binge eating/purging (Racine & Wildes, 2013), above and beyond other dimensions of emotion regulation. Finally, experience sampling studies indicate that individuals are more likely to engage in risky behaviors on days when they experienced intense negative and/or positive emotions (Fortenberry et al., 2005; Smyth et al., 2007).

Notably, however, despite growing evidence that negative and positive emotional states influence engagement in impulsive behaviors in general, there is a dearth of research on the emotion-dependent nature of distinct, clinically-relevant, risky behaviors. Likely contributing to the lack of research in this area is the absence of a comprehensive measure that assesses the tendency to engage in clinically-relevant risky behaviors in the context of negative and positive emotions. Assessment of the emotion-dependent nature of specific risky behaviors may improve our understanding of the particular emotional contexts in which these behaviors may be more likely to occur. Indeed, although the vast majority of interventions aimed at reducing risky behaviors among SUD patients focus on negative (vs. positive) emotional experiences, a growing body of research underscores the key role of positive emotions in risky behaviors. For instance, theory suggests that individuals often engage in risky behaviors to elicit, maintain, and enhance positive emotional states (e.g., Cox & Klinger, 1988; Nock & Prinstein, 2004), consistent with evidence that the tendency to act rashly in the context of positive emotions is related to specific risky behaviors (Cyders & Smith, 2008). Research examining the unique relevance of positive and negative emotional arousal to specific risky behaviors may suggest important targets for interventions and inform efforts to increase the efficacy of existing interventions.

The goals of the present study were twofold. First, we sought to develop and validate a measure of the frequency of distinct, clinically-relevant, risky behaviors, as well as the tendency to engage in these behaviors in the context of negative and positive emotional arousal. Second, we examined the relative and unique relations of tendencies to engage in risky behaviors in the context of negative and positive emotional arousal to both overall risky behaviors and specific risky behaviors (including substance use frequency, deliberate self-harm, risky sexual behavior, and criminal behavior) among SUD patients. No a priori hypotheses were made regarding the unique relations of the tendency to engage in risky behaviors in the context of negative and positive emotional arousal to specific risky behaviors.

Methods

Procedures and Participants

Data were collected as part of a larger study examining risk-taking among patients in a residential SUD treatment facility in central Mississippi (comprised of both female and male units). All procedures were reviewed and approved by the relevant Institutional Review Boards. Study personnel split their time between the female and male units; patients were recruited no sooner than 72 hours after entry in the facility (to limit the possible interference of withdrawal symptoms). To be eligible for inclusion in the larger study, SUD patients were required to have: (a) dependence on alcohol and/or cocaine; (b) a Mini-Mental Status Exam (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) score of ≥24; and (c) no current psychotic disorders (as determined by the MINI; Sheehan et al., 1998). Potential participants were provided with information about study procedures and associated risks, following which written informed consent was obtained. Although the larger study involved three separate sessions, the present study uses data from only the first session. Participants were remunerated $25 for completing this session.

A total of 226 SUD patients participated in the first session. Twenty-two participants did not complete the primary study measure (Risky Behavior Questionnaire; RBQ) and an additional 28 were missing extensive data on this measure; thus, these participants were excluded from analyses. The final sample for this study included 176 SUD patients. Participants (53.4% female) ranged in age from 18 to 65 (M age = 34.18±10.07). In terms of racial/ethnic background, 65.3% of participants self-identified as White and 32.4% as Black/African American. Almost half of the participants reported an annual income under $10,000 (49.4%), and 59.7% had no higher than a high school education. Most participants reported that they were unemployed (71.6%). There were no significant differences in demographic variables between participants who completed the RBQ and those who did not.

Measures

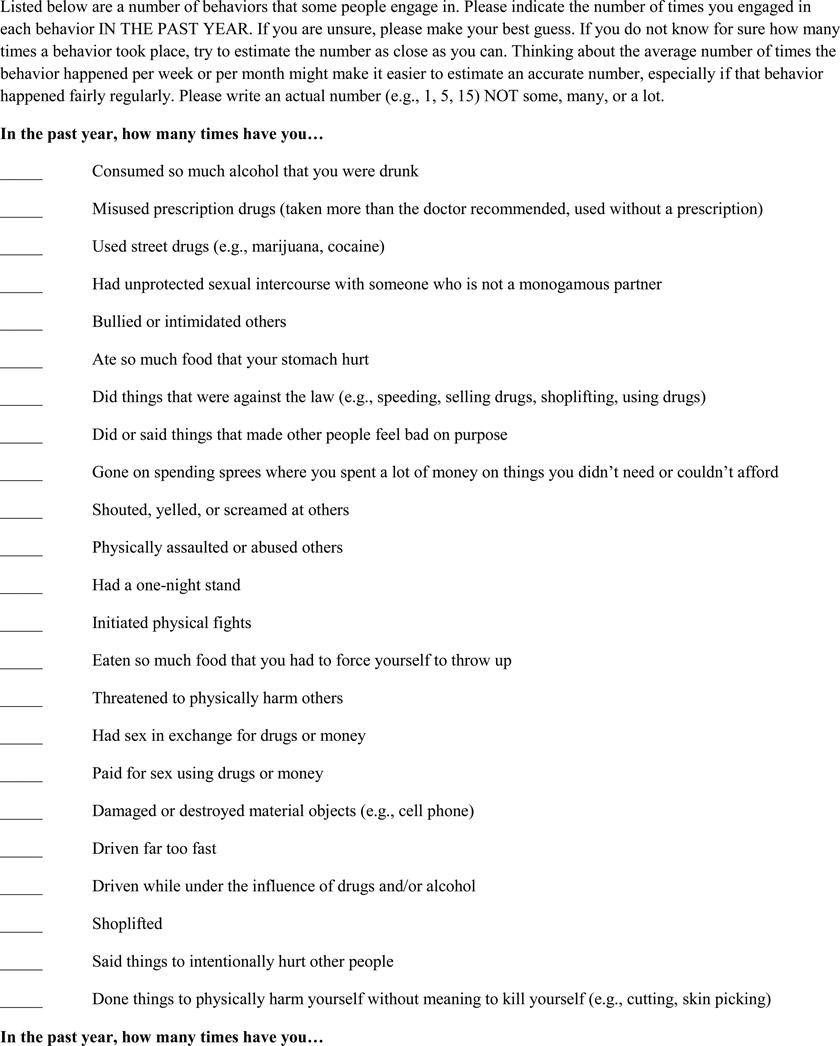

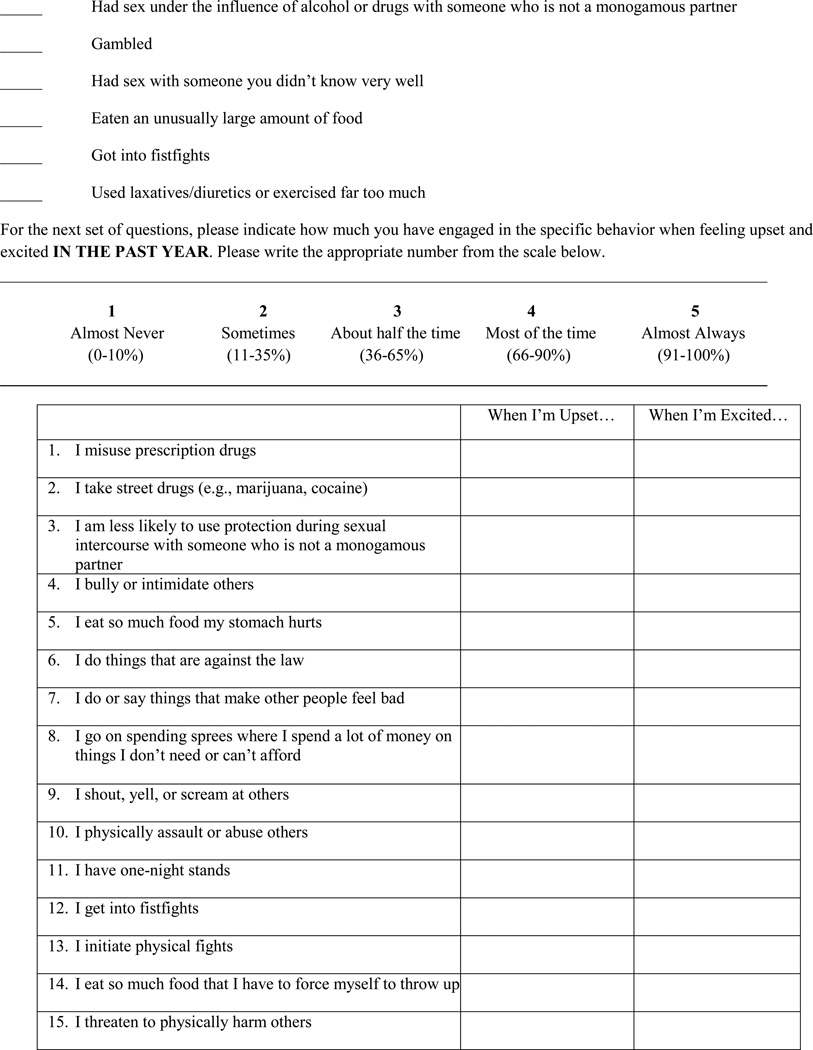

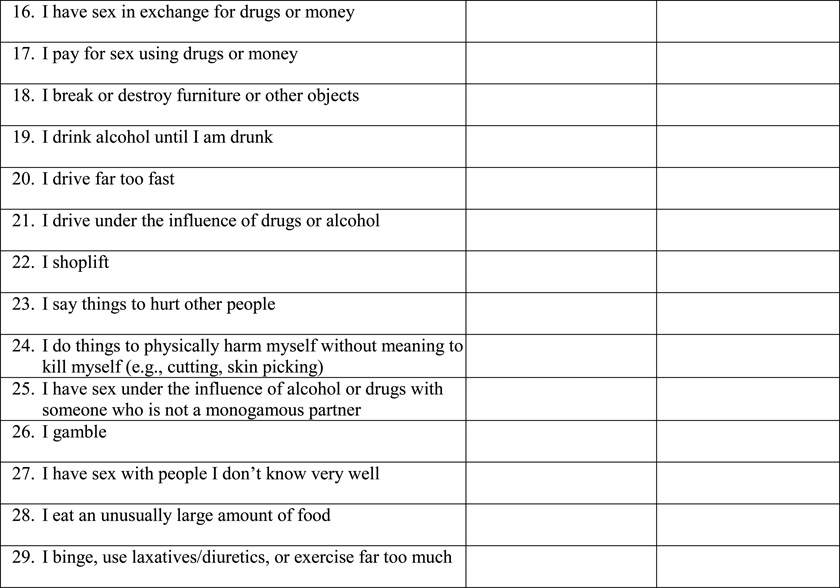

Risky Behaviors

The Risky Behavior Questionnaire (RBQ) is an 89-item, self-report measure developed for the purposes of this study to assess: (1) the frequency of past-year clinically-relevant risky behaviors (RBQ Frequency), (2) the tendency to engage in distinct risky behaviors in the context of negative emotional arousal (RBQ Negative), and (3) the tendency to engage in distinct risky behaviors in the context of positive emotional arousal (RBQ Positive; see Appendix A). The behaviors included in the 29-item RBQ Frequency Scale were selected on the basis of clinical relevance. Specifically, author NHW conducted a literature review to identify specific, clinically-relevant risky behaviors (e.g., behaviors common in clinical populations; behaviors associated with negative clinical outcomes; behaviors assessed by other measures, such as the BPD module of the DIPD-IV[Zanarini et al., 1996] and the Impulsive Behavior Scale [Rossotto, Yager, & Rorty, 1998]), following which a consensus meeting of all authors was conducted to identify any additional behaviors and determine the final behaviors to be included in the measure. Participants are asked to report the frequency with which they engaged in each of the behaviors during the past year; these scores are then summed to create a total Frequency variable. The 30 items on the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales were modeled after the RBQ Frequency Scale, with items modified to assess the tendency to engage in each of the risky behaviors in the context of negative and positive emotional arousal, respectively. Specifically, the RBQ Negative Scale began with the stem “When I’m upset,” whereas the RBQ Positive Scale began with the stem “When I’m excited.” Participants rate each item using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = almost never, 5 = almost always). Responses to items on the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales were summed so that higher scores indicated a greater tendency to engage in risky behaviors in the context of negative and positive emotional arousal, respectively.

The risky behaviors criterion of the BPD module of the DIPD-IV(Zanarini et al., 1996) was used as an index of clinically-relevant patterns of overall risky behaviors. The items assess the presence of clinically-relevant patterns of 12 risky behaviors during the past two years (e.g., substance use, risky sex). Behaviors endorsed by the participant as occurring regularly are considered “present” and scored a 1; behaviors that occurred infrequently or never are scored a 0. Scores for each of the behaviors are then summed to create an index of the total number of risky behaviors the participant has engaged in regularly during the past two years. Interviews were administered by clinical assessors trained to reliability with the principal investigator and reviewed by a PhD level clinician, with diagnoses confirmed in consensus meetings.

The Drug Use Questionnaire (DUQ; Hien & First, 1991) is a 13-item self-report measure used to assess frequency of substance use over the past year. Participants rate the frequency with which they have used each substance on a 6-point Likert-type scale (0 = never; 1 = one time;2 = monthly or less; 3 = 2–4 times per month; 4 = 2–3 times per week; 5 = 4 or more times per week). Responses are summed to create an overall score of past-year substance use.

The Deliberate Self-harm Inventory (DSHI; Gratz, 2001) is a 17-item self-report measure that assesses deliberate self-harm (e.g. cutting, burning, biting). A deliberate self-harm frequency variable was computed by summing the total number of deliberate self-harm episodes reported.

The TCU HIV/AIDS Risk Assessment (Simpson, 1997) is a self-report measure of risky sexual behavior. For this study, participants were only asked about the frequency with which they engaged in risky sexual behavior (e.g., sex without a condom with someone who is not their spouse/primary partner, sex while high on drugs or alcohol, trading sex for drugs/money/gifts) during the month prior to entering treatment. Participants’ responses to these items were summed to create a continuous score reflecting frequency of past month risky sexual behavior.

Selected items from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1992) were utilized to assess criminal behavior. Specifically, participants responded to three items: (a) total lifetime criminal convictions, (b) total lifetime months incarcerated, and (c) the number of days with which they engaged in criminal behavior during the month prior to entering treatment.

Emotion Dysregulation

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) is a 36-item self-report measure that assesses individuals’ typical levels of emotion dysregulation. The overall DERS scale and the difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed subscale (DERS-Impulse) were utilized in the present study (αs = .96 and .87 in this sample). The DERS and its subscales demonstrate good construct and predictive validity (Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Gratz & Tull, 2010). Participants rate each item using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = almost never, 5 = almost always). Higher scores indicate greater emotion dysregulation.

The Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, Sensation Seeking, and Positive Urgency Impulsive Behavior Scale(UPPS-P; Cyders et al., 2007; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001) is a 59-item self-report measure that assesses five domains of impulsivity. The negative and positive urgency subscales were utilized in the present study (αs = .85 and .89 in this sample). Participants rate the extent to which each item applies to them on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = rarely/never true, 4 = almost always/always true). Higher scores indicate greater negative and positive urgency.

The Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS; Simons & Gaher, 2005) is a 15-item self-report measure examining the degree to which individuals experience negative emotions as intolerable. Participants rate the extent to which each item applies to them on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly agree, 4 = strongly disagree). Lower scores indicate a tendency to experience distress as unacceptable. Internal consistency in this sample was adequate (α = .85).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

As recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), all study variables were examined for assumptions of normality. Variables exhibiting non-normal distributions (i.e., the RBQ Frequency and measures of deliberate self-harm, risky sexual behavior, and criminal behavior) were square-root transformed. Of note, the below results remain the same in strength and direction when non-transformed variables are used.

Psychometric Properties of the RBQ

Factor analysis

To test the factor structure of the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales, two separate exploratory factor analyses (EFA) were conducted using the principal axis factoring extraction method and promax oblique rotation (allowing factors to be correlated), first with the 30 RBQ Negative items and then with the 30 RBQ Positive items. Separate EFAs for the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales were conducted because they share the same wording and, thus, would demonstrate too much overlap to consider within a single EFA. The scree test suggested retaining one factor for both the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales, consistent with findings of higher eigenvalues and % variance for the first factor of each scale (Negative: 8.95 and 30.85%, respectively; Positive: 10.07 and 34.71%, respectively) than the second, third, and fourth factors (Negative: eigenvalues = 2.86, 2.12, and 1.69, respectively, % variance = 9.86, 7.32, and 5.83, respectively; Positive: eigenvalues = 2.86, 1.82, and 1.61, respectively, % variance = 9.87, 6.27, and 5.56, respectively). Parallel analysis was also used to identify the number of underlying factors. Contrary to the results of the scree test, results of this analysis suggested retaining four factors for the RBQ Negative Scale and three factors for the RBQ Positive Scale. However, when factor analyses were conducted selecting for this number of factors, none of the items loaded uniquely on any of the factors other than the first. Thus, these findings provide additional support for the unidimensional nature of the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales.

Assignment of items to factors was based on factor loadings of ≥ .40. Item 1 on the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales was deleted (“When I’m upset, I drink alcohol” and “When I’m excited, I drink alcohol”), with loadings of .12 and .31, respectively. Item 20 demonstrated an adequate factor loading on the RBQ Positive Scale (“When I’m excited, I drink alcohol until I am drunk”), but not the RBQ Negative Scale (“When I’m upset, I drink alcohol until I am drunk”), with loadings of .42 and .26, respectively. Likewise, Item 29 demonstrated an adequate factor loading on the RBQ Positive Scale (“When I’m upset, I eat an unusually large amount of food”), but not the RBQ Negative Scale (“When I’m excited, I eat an unusually large amount of food”), with loadings of .54 and .38, respectively. Item 2 did not demonstrate an adequate factor loading on the RBQ Negative Scale (“When I’m upset, I misuse prescription drugs”) or the RBQ Positive Scale (“When I’m excited, I misuse prescription drugs”), with loadings of .39 and .36, respectively. Despite having factor loadings of < .40, we decided to retain Items 2 and 20 because these were the only items that assessed alcohol and prescription drug misuse – key risky behaviors in the extant literature that may not have performed as well in this sample of SUD patients simply because the vast majority of participants reported recent alcohol and drug use. We chose to retain Item 20 over Item 1 because (a) the factor loading for Item 20 on the RBQ Positive Scale was adequate, whereas Item 1 demonstrated low factor loadings on both the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales; and (b) Item 20 assesses problematic alcohol use, whereas Item 1 assesses only alcohol use in general (which, when not in excess, is not inherently risky). Finally, we decided to retain Item 29 despite it having low loadings on the RBQ Negative Scale because it loaded adequately on the RBQ Positive Scale.

After excluding Item 1, the EFAswere conducted a second time on the remaining 29 items (see Tables 1 and 2). Upon extraction, the one factor solutionfor the RBQ Negative Scale accounted for 28.53% of the total variance of the variables (Extraction Sums of Squares Loadings = 8.27), whereas the one factor solution for the RBQ Positive Scale accounted for 32.46% of the total variance of the variables (Extraction Sums of Squares Loadings = 9.41).

Table 1.

Factor loadings for the 29 Risky Behavior Questionnaire Negative Scale items included in the final factor analysis

| When I’m upset… | Factor 1 |

|---|---|

| Item 16. I threaten to physically harm others | .74 |

| Item 11. I physically assault or abuse others | .72 |

| Item 13. I get into fistfights | .67 |

| Item 14. I initiate physical fights | .66 |

| Item 19. I break or destroy furniture or other objects | .64 |

| Item 26. I have sex under the influence of alcohol/drugs with a nonmonogamous partner | .63 |

| Item 5. I bully or intimidate others | .58 |

| Item 12. I have one-night stands | .61 |

| Item 28. I have sex with people I don’t know very well | .59 |

| Item 21. I drive far too fast | .58 |

| Item 24. I say things to hurt other people | .54 |

| Item 17. I have sex in exchange for drugs or money | .54 |

| Item 7. I do things that are against the law | .53 |

| Item 9. I go on spending sprees where I spend a lot of money on things I don’t need or can’t afford | .51 |

| Item 22. I drive under the influence of drugs or alcohol | .50 |

| Item 25. I do things to physically harm myself without meaning to kill myself | .49 |

| Item 27. I gamble | .49 |

| Item 8. I do or say things that make other people feel bad | .49 |

| Item 15. I eat so much food that I have to force myself to throw up | .49 |

| Item 18. I pay for sex using drugs or money | .49 |

| Item 10. I shout, yell, or scream at others | .46 |

| Item 23. I shoplift | .46 |

| Item 3. I take street drugs (e.g., marijuana, cocaine) | .46 |

| Item 4. I am less likely to use protection during sexual intercourse with a nonmonogamous partner | .45 |

| Item 30. I binge, use laxatives/dietetics, or exercise far too much | .44 |

| Item 6. I eat so much food my stomach hurts | .43 |

| Item 2. I misuse prescription drugs | .39 |

| Item 29. I eat an unusually large amount of food | .38 |

| Item 20. I drink alcohol until I am drunk | .26 |

Table 2.

Factor loadings for the 29 Risky Behavior Questionnaire Positive Scale items included in the final factor analysis

| When I’m Excited… | Factor 1 |

|---|---|

| Item 16. I threaten to physically harm others | .70 |

| Item 25. I do things to physically harm myself without meaning to kill myself | .68 |

| Item 8. I do or say things that make other people feel bad | .66 |

| Item 19. I break or destroy furniture or other objects | .65 |

| Item 11. I physically assault or abuse others | .65 |

| Item 15. I eat so much food that I have to force myself to throw up | .65 |

| Item 13. I get into fistfights | .63 |

| Item 28. I have sex with people I don’t know very well | .63 |

| Item 14. I initiate physical fights | .62 |

| Item 18. I pay for sex using drugs or money | .61 |

| Item 24. I say things to hurt other people | .60 |

| Item 30. I binge, use laxatives/dietetics, or exercise far too much | .60 |

| Item 5. I bully or intimidate others | .59 |

| Item 12. I have one-night stands | .57 |

| Item 10. I shout, yell, or scream at others | .57 |

| Item 26. I have sex under the influence of alcohol/drugs with a nonmonogamous partner | .57 |

| Item 23. I shoplift | .57 |

| Item 29. I eat an unusually large amount of food | .54 |

| Item 17. I have sex in exchange for drugs or money | .53 |

| Item 6. I eat so much food my stomach hurts | .53 |

| Item 7. I do things that are against the law | .52 |

| Item 9. I go on spending sprees where I spend a lot of money on things I don’t need or can’t afford | .52 |

| Item 21. I drive far too fast | .52 |

| Item 22. I drive under the influence of drugs or alcohol | .51 |

| Item 4. I am less likely to use protection during sexual intercourse with a nonmonogamous partner | .49 |

| Item 3. I take street drugs (e.g., marijuana, cocaine) | .45 |

| Item 20. I drink alcohol until I am drunk | .42 |

| Item 27. I gamble | .41 |

| Item 2. I misuse prescription drugs | .36 |

Internal consistency

Cronbach’s alphas were calculated to determine the internal consistency of the RBQ Frequency, Negative, and Positive Scales. Results revealed high internal consistency for the RBQ Negative (α = .91) and Positive (α = .92) Scales. As expected, a relatively low alpha coefficient was detected for the RBQ Frequency Scale (α = .52) given the checklist nature of this scale (Streiner, 2003).

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations

Descriptive data for the RBQ Frequency Scale is provided in Table 3. Scores ranged from 0 to 650 (M = 31.61, SD = 59.79) on the RBQ Frequency Scale; from 0 to 145 (M = 41.15, SD = 23.68) on the RBQ Negative Scale; and from 0 to 145 (M = 33.46, SD = 23.01) on the RBQ Positive Scale.

Table 3.

Descriptive data for the Risky Behavior Questionnaire Frequency Scale

| Risky Behavior Questionnaire Frequency Scale Items | % Endorsed | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Item 10. Shouted, yelled, or screamed at others | 88.8% (n = 159) | 52.99 (123.03) |

| Item 7. Did things that were against the law (e.g., speeding, selling drugs, shoplifting) | 84.4% (n = 151) | 179.76 (105.21) |

| Item 3. Used street drugs (e.g., marijuana, cocaine) | 83.8% (n = 150) | 128.87 (204.94) |

| Item 1. Consumed so much alcohol that you were drunk | 82.7% (n = 148) | 78.85 (135.14) |

| Item 20. Driven while under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol | 79.3% (n = 142) | 59.77 (121.70) |

| Item 8. Did or said things that made other people feel bad on purpose | 77.0% (n = 137) | 37.29 (117.18) |

| Item 22. Said things to intentionally hurt other people | 71.6% (n = 126) | 27.76 (92.36) |

| Item 9. Spent a lot of money on things you didn’t need or couldn’t afford | 70.2% (n = 125) | 23.08 (80.83) |

| Item 2. Misused prescription drugs | 65.5% (n = 116) | 69.91 (141.42) |

| Item 12. Had a one night stand | 60.9% (n = 109) | 9.30 (36.99) |

| Item 18. Damaged or destroyed material objects (e.g., cell phone) | 60.9% (n = 109) | 9.13 (23.89) |

| Item 4. Had unprotected sexual intercourse with someone who is not a monogamous partner | 60.5% (n = 107) | 25.64 (144.45) |

| Item 24. Had sex under the influence of drugs/alcohol with a nonmomgomous partner | 59.9% (n = 103) | 14.75 (41.69) |

| Item 19. Driven far too fast | 59.2% (n = 106) | 25.87 (143.30) |

| Item 26. Had sex with someone you didn’t know very well | 56.3% (n = 99) | 8.44 (37.14) |

| Item 6. Ate so much food that your stomach hurt | 53.1% (n = 95) | 14.17 (44.56) |

| Item 27. Eaten an unusually large amount of food | 51.1% (n = 90) | 11.40 (40.56) |

| Item 28. Got into fistfights | 49.2% (n = 87) | 6.15 (29.79) |

| Item 25. Gambled | 48.6% (n = 85) | 19.56 (88.22) |

| Item 13. Initiated physical fights | 44.1% (n = 79) | 7.80 (31.04) |

| Item 15. Threatened to physically harm others | 42.5% (n = 76) | 12.09 (50.32) |

| Item 5. Bullied or intimidated others | 32.8% (n = 58) | 13.42 (85.12) |

| Item 11. Physically assaulted or abused others | 39.7% (n = 71) | 6.65 (31.24) |

| Item 21. Shoplifted | 36.7% (n = 65) | 12.86 (48.51) |

| Item 16. Had sex in exchange for drugs or money | 34.1% (n = 61) | 11.18 (46.53) |

| Item 23. Done things to physically harm yourself without meaning to kill yourself | 27.1% (n = 48) | 4.84 (29.50) |

| Item 17. Paid for sex using drugs or money | 19.6% (n = 35) | 2.05 (9.94) |

| Item 14. Eaten so much food that you had to force yourself to throw up | 19.0% (n = 34) | 4.61 (34.98) |

| Item 29. Used laxatives/diuretics or exercised far too much | 17.1% (n = 30) | 4.59 (28.28) |

Pearson product-moment correlations were conducted to examine intercorrelations among the RBQ Scales. The RBQ Frequency Scale was significantly positively correlated with the RBQ Negative (r = .51, p< .001) and Positive (r = .47, p< .001) Scales. The RBQ Negative Scale was significantly positively correlated with the RBQ Positive Scale (r = .78, p< .001).

Analyses of variance and Pearson product-moment correlations were conducted to explore whether scores on the RBQ Scales vary as a function of demographic variables. Given the small number of participants in several of the racial/ethnic, education, past-year income, and employment categories, these variables were collapsed into dichotomous variables of White (65.3%) versus Non-White (34.7%); over (50.6%) versus under (49.4%) $10,000 per year; high school diploma or less (59.7%) versus education beyond high school (40.3%); and unemployed (71.6%) versus employed (28.4%). No significant differences were detected for race/ethnicity, education, past-year income, and employment on the RBQ Scales (Fs [1–3, 161–175] < 3.01, ps > .05); however, scores on the RBQ Negative Scale were significantly negatively related to age (r = −.18, p = .02), and scores on the RBQ Positive Scale were significantly higher among men (M = 38.58, SD = 20.48) versus women (M = 29.06, SD = 24.25; F [1, 156] = 6.22, p = .01).

Construct validity

Pearson product-moment correlations were conducted to evaluate the construct validity of the RBQ Frequency, Negative, and Positive Scales (see Table 4). The RBQ Scales were significantly positively associated with all measures of risky behaviors and emotion dysregulation with a few exceptions: the RBQ Frequency Scale was not significantly related to total months incarcerated, overall emotion dysregulation, difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed, or distress tolerance. Results remained the same in strength and direction when the RBQ items that overlapped with the risky behavior outcomes were excluded, with two exceptions: the RBQ Positive Scale was no longer significantly related to risky sexual behavior (r = .13, p = .09) or total months incarcerated (r = .15, p = .07).

Table 4.

Correlations of the Risky Behavior Questionnaire (RBQ) Frequency, Negative, and Positive Scales withrisky behaviors and emotion dysregulation

| RBQ Frequency | RBQ Negative | RBQ Positive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risky Behaviors | |||

| Clinically-relevant patterns on DIPD-IV | .22** | .45*** | .33*** |

| Substance use severity | .44*** | .49*** | .60*** |

| Deliberate self-harm | .22** | .32*** | .17* |

| Risky sexual behavior | .27*** | .33*** | .29*** |

| Total criminal convictions | .25** | .33*** | .26** |

| Total months incarcerated | .01 | .22** | .17* |

| Past month criminal behavior | .26** | .38*** | .26** |

| Emotion Regulation | |||

| DERS overall emotion dysregulation | .12 | .35*** | .28*** |

| DERS difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when upset | .11 | .34*** | .27** |

| UPPS-P negative urgency | .20** | .43*** | .25** |

| UPPS-P positive urgency | .19* | .33*** | .34*** |

| DTS distress tolerance | .03 | −.21** | −.22** |

Note. DIPD = Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders; DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; UPPS-P = Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, Sensation Seeking, and Positive Urgency Impulsive Behavior Scale; DTS = Distress Tolerance Scale.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Incremental validity

Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine the incremental validity of the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales in relation to risky behaviors above and beyond related constructs. Results of the final step of each analysis are presented in Table 5. For analyses examining the RQB Negative Scale, the UPPS-P Negative Urgency Scale and DERS Impulse Scale were entered in the first step and the RBQ Negative Scale was entered in the second step. The RBQ Negative Scale demonstrated incremental validity in relation to the RBQ Frequency Scale, clinically-relevant patterns of risky behaviors on the DIPD-IV, substance use frequency, risky sexual behavior, total criminal convictions, total months incarcerated, and past month criminal behavior above and beyond the UPPS-P Negative Urgency and DERS Impulse Scales (ΔR2> .03, ps < .05), whereas the UPPS-P Negative Urgency and DERS Impulse Scales were not significant in the final step of these models (see Table 5). In terms of deliberate self-harm, the RBQ Negative, UPPS-P Negative Urgency, and DERS Impulse Scales all emerged as significant predictors. For analyses examining the RQB Positive Scale, the UPPS-P Positive Urgency Scale was entered in the first step and the RBQ Positive Scale was entered in the second step. The RBQ Positive Scale demonstrated incremental validity in relation to the RBQ Frequency Scale, clinically-relevant patterns of risky behaviors on the DIPD-IV, substance use frequency, risky sexual behavior, total criminal convictions, and past month criminal behavior above and beyond the UPPS-P Positive Urgency Scale (ΔR2> .06, ps < .01), whereas the Positive Urgency Scale did not contribute significantly to these models (see Table 5). Results remained the same in strength and direction when the RBQ items that overlapped with the risky behavior outcomes were excluded.

Table 5.

Final step of hierarchical regression analyses examining the incremental validity of the Risky Behavior Questionnaire (RBQ) Negative and Positive Scales relative to negative and positive urgency and difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when upsetin predicting risky behaviors

| Negative | Positive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | t | R2 | F | B | t | R2 | F | |

| RBQ Frequency | .26 | 17.59*** | .22 | 20.93*** | ||||

| Urgency | −0.05 | −0.20 | 0.04 | 0.19 | ||||

| DERS Impulse | −0.11 | −0.46 | -- | -- | ||||

| RBQ Scale | 0.40 | 6.70*** | 0.38 | 6.02*** | ||||

| DIPD Item 85 | .20 | 12.88*** | .10 | 9.12*** | ||||

| Urgency | 0.06 | 1.44 | 0.05 | 1.39 | ||||

| DERS Impulse | 0.04 | 1.00 | -- | -- | ||||

| RBQ Scale | 0.05 | 4.31*** | 0.04 | 3.33*** | ||||

| Substance use severity | .30 | 21.79*** | .33 | 36.99*** | ||||

| Urgency | 0.14 | 1.05 | 0.14 | 1.32 | ||||

| DERS-Impulse | −0.08 | −0.66 | -- | -- | ||||

| RBQ Scale | 0.23 | 6.90*** | 0.25 | 7.56*** | ||||

| Deliberate self-harm | .21 | 13.45*** | .02 | 2.46 | ||||

| Urgency | 0.02 | 2.37* | 0.01 | 1.25 | ||||

| DERS Impulse | 0.03 | 2.61* | -- | -- | ||||

| RBQ Scale | 0.01 | 2.35* | 0.004 | 1.31 | ||||

| Risky sexual behaviors | .12 | 6.39*** | .10 | 8.75*** | ||||

| Urgency | 0.06 | 1.04 | 0.09 | 1.77 | ||||

| DERS Impulse | −0.01 | −0.16 | -- | -- | ||||

| RBQ Scale | 0.05 | 3.43** | 0.05 | 3.05** | ||||

| Total criminal convictions | .13 | 7.48*** | .05 | 5.15** | ||||

| Urgency | 0.03 | 1.85 | 0.01 | 0.34 | ||||

| DERS Impulse | −0.02 | −1.40 | -- | -- | ||||

| RBQ Scale | 0.01 | 3.44** | 0.01 | 2.89** | ||||

| Total months incarcerated | .05 | 2.59 | .02 | 2.12 | ||||

| Urgency | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.64 | ||||

| DERS Impulse | −0.04 | −1.15 | -- | -- | ||||

| RBQ Scale | 0.02 | 2.48* | 0.02 | 1.63 | ||||

| Past-month criminal behavior | .18 | 10.12*** | .07 | 6.02** | ||||

| Urgency | −0.01 | −0.48 | −0.01 | −0.27 | ||||

| DERS Impulse | −0.04 | −1.49 | -- | -- | ||||

| RBQ Scale | 0.03 | 5.37*** | 0.02 | 3.33*** | ||||

Note. RBQ Frequency = frequency of past-year risky behaviors; Urgency = negative urgency or positive urgency on the UPPS-P; DERS Impulse = difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when upset on the DERS; DIPD Item 85 = clinically-relevant pattern of risky behaviors on the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Unique Relations of RBQ Negative and Positive Scales with Specific Risky Behaviors

Identification of covariates

Analyses of variance and Pearson product-moment correlations were conducted to explore the impact of demographic variables on the risky behavior outcomes. Gender was significantly related to total criminal convictions (F [1, 166] = 8.88, p = .003) and total months incarcerated (F [1, 166] = 16.72, p< .001), with men reporting a greater frequency than women; education was significantly related to clinically-relevant patterns of risky behaviors on the DIPD-IV (F [1, 175] = 5.00, p = .03) and total months incarcerated (F [1, 169] = 7.73, p = .01), with participants with a high school diploma or less reporting a greater frequency than those with an education beyond high school; race/ethnicity was significantly associated with the RBQ Frequency Scale (F [1, 175] = 19.81, p< .001), clinically-relevant patterns of risky behaviors on the DIPD-IV (F [1, 175] = 4.60, p = .03), substance use frequency (F [1, 174] = 39.61, p< .001), deliberate self-harm (F [1, 172] = 5.84, p = .02), and risky sexual behavior (F [1, 166] = 8.07, p = .01), with White participants reporting a greater frequency of these behaviors than non-White participants; employment status was significantly related to clinically-relevant patterns of risky behaviors on the DIPD-IV (F [1, 175] = 6.59, p = .01) and risky sexual behavior (F [1, 166] = 4.49, p = .04), with unemployed participants reporting a greater frequency of these behaviors than employed participants; and age was significantly negatively associated with the RBQ Frequency Scale (r = −.19,p = .01), clinically-relevant patterns of risky behaviors on the DIPD-IV (r = −.16, p = .03), and substance use frequency (r = −.35, p< .001). Subsequent analyses included the demographic variables significantly associated with each of the respective the dependent variables.

Regression analyses

A series of hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to explore the relative and unique relations of RBQ Negative and Positive Scales to the risky behavior outcomes above and beyond identified covariates. Identified covariates were entered in the first step of each model, followed by the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales in the second step. Results of the final step of these analyses are presented in Table 6. Of note, the addition of the RBQ scales in the second step of each analysis significantly improved the models (ΔR2> .06, ps < .01). In the final step of the analyses, the RBQ Negative Scale was found to be uniquely related to clinically-relevant patterns of risky behaviors on the DIPV-IV, deliberate self-harm, risky sexual behavior, total criminal convictions, total months incarcerated, and past month criminal behavior above and beyond relevant demographic variables and the RBQ Positive Scale (see Table 6). The RBQ Positive Scale was found to be uniquely associated with substance use frequency above and beyond relevant demographic variables and the RBQ Negative Scale (see Table 6). Both the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales were uniquely associated with the RBQ Frequency Scale (see Table 6). Results remained the same in strength and direction when the RBQ items that overlapped with the risky behavior outcomes were excluded, with one exception: the RBQ Negative Scale was no longer significantly related to risky sexual behavior (B = .04, p = .11).

Table 6.

Final step of hierarchical regression analyses examining the unique relations of the Risky Behavior Questionnaire Negative and Positive Scales to risky behaviors

| B | t | R2 | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBQ Frequency | .30 | 17.64*** | ||

| Age | −0.21 | −1.73 | ||

| Race/ethnicity (White) | 7.17 | 2.74** | ||

| RBQ Negative | 0.20 | 2.37* | ||

| RBQ Positive | 0.19 | 1.23* | ||

| DIPD Item 85 | .26 | 9.90*** | ||

| Age | 0.002 | 0.08 | ||

| Race/ethnicity (White) | 0.96 | 1.89 | ||

| Education | −1.26 | −2.65** | ||

| Employment | 1.14 | 2.30* | ||

| RBQ Negative | 0.07 | 4.74*** | ||

| RBQ Positive | −0.02 | −1.22 | ||

| Substance use severity | .52 | 41.07*** | ||

| Age | −0.26 | 4.42*** | ||

| Race/ethnicity (White) | 0.28 | 4.89*** | ||

| RBQ Negative | −0.02 | −0.25 | ||

| RBQ Positive | 0.56 | 6.16*** | ||

| Deliberate self-harm | .09 | 6.27*** | ||

| Race/ethnicity (White) | 0.17 | 1.37 | ||

| RBQ Negative | 0.01 | 3.31*** | ||

| RBQ Positive | −0.01 | −1.27 | ||

| Risky sexual behaviors | .11 | 5.75*** | ||

| Race/ethnicity (White) | 0.86 | 1.31 | ||

| Employment | 0.97 | 1.48 | ||

| RBQ Negative | 0.04 | 1.98* | ||

| RBQ Positive | 0.02 | 0.73 | ||

| Total criminal convictions | .17 | 10.89*** | ||

| Gender (male) | 0.55 | 3.10** | ||

| RBQ Negative | 0.02 | 3.78*** | ||

| RBQ Positive | −0.01 | −1.19 | ||

| Total months incarcerated | .16 | 8.24*** | ||

| Gender (male) | 1.58 | 3.75*** | ||

| Education | −0.87 | −2.17* | ||

| RBQ Negative | 0.04 | 2.90** | ||

| RBQ Positive | −0.02 | −1.41 | ||

| Past-month criminal behavior | .14 | 12.82*** | ||

| RBQ Negative | 0.04 | 3.63*** | ||

| RBQ Positive | −0.01 | −1.00 |

Note. RBQ Frequency = frequency of past-year risky behaviors; DIPD Item 85 = clinically-relevant pattern of risky behaviors on the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders; Education: 0 = high school equivalent or less, 1 = at least some college; Employment: 0 = unemployed, 1 = employed.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Discussion

The present study sought to develop a measure of the frequency and emotion-dependent context of a variety of clinically-relevant risky behaviors, as well as to examine the unique relations of the overall tendency to engage in risky behaviors in the context of negative versus positive emotional arousal to specific risky behaviors in SUD patients. Several important findings stem from our assessment of the psychometric properties of the RBQ. First, results of exploratory factor analyses suggest that the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales are unitary constructs. Whereas the vast majority of research to date has focused on specific types of risky behaviors, this finding suggests that there may be an underlying general tendency toward engagement in risky behaviors in the context of negative and positive emotions among SUD patients that generalizes across risky behaviors. This result has important implications for research and clinical practice. In addition to highlighting the importance of comprehensive assessments of risky behaviors in research and clinical settings (even among populations characterized primarily by one specific type of risky behaviors, e.g., substance use), findings that the link between emotional states and engagement in risky behaviors may be common across risky behaviors is crucial to treatment planning. Indeed, although preliminary, our findings underscore the potential utility of integrated treatments that address underlying emotional states associated with engagement in risky behaviors in general (vs. focusing on specific risky behaviors). Such interventions would likely be more efficient and cost-effective than those focusing on specific individual risky behaviors. Moreover, interventions targeting factors underlying multiple risky behaviors may reduce the likelihood of individuals replacing one risky behavior with another.

Indeed, research focused on identifying higher-order, transdiagnostic factors has grown substantially in recent years (e.g., Harvey, Watkins, Mansell, & Shafran, 2004), with the results of these studies informing the development of treatments that target these common factors (e.g., the unified protocol for mood and anxiety disorders [Barlow et al., 2010]; broad-spectrum cognitive-behavioral group for anxiety [Norton & Hope, 2005]; transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders [Fairburn, Cooper, & Shafran, 2003]). Our findings provide support for the potential utility of interventions targeting common, higher order factors of risky behaviors (e.g., negative and positive emotion-driven impulsivity). One promising option in this regard is emotion regulation group therapy (ERGT; Gratz, Tull & Levy, 2014) – a treatment developed specifically to target emotion regulation difficulties (including emotion-driven impulse control difficulties) that has been found to have positive effects on overall risky behaviors (Gratz et al., 2014).

The results of this study also provide preliminary support for the utility and validity of the RBQ in the assessment of the frequency and emotion-dependent nature of clinically-relevant risky behaviors. In addition to evidencing significant associations with relevant emotional and behavioral constructs, the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales demonstrated incremental validity in the prediction of most risky behaviors above and beyond negative and positive urgency on the UPPS-P and difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed on the DERS. These findings suggest that the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales contribute to the understanding of risky behaviors above and beyond existing empirically-supported measures of related constructs. The relative utility of the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales in predicting specific risky behaviors may be due to their focus on the emotion-dependent nature of specific clinically-relevant risky behaviors, rather than the tendency to act impulsively in general in the context of negative and positive emotional arousal as in the UPPS-P and DERS scales.

Our findings extend extant research on the emotion-dependent nature of risky behaviors. Consistent with past research, the RBQ Negative Scale was uniquely associated with deliberate self-harm, risky sexual behavior, and criminal behavior within this sample, suggesting a robust association between the tendency to engage in risky behaviors in the context of negative emotions and multiple specific risky behaviors among SUD patients. However, results of this study also provide support for the role of positive emotions in certain risky behaviors within this sample, revealing a unique association between the RBQ Positive Scale and substance use frequency. These findings suggest that whereas prevention and intervention efforts targeting deliberate self-harm and criminal behavior may benefit from focusing on negative emotions, efforts to reduce substance use may benefit from a focus on positive emotions, at least among SUD patients. In addition, whereas both the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales were unique predictors of the RBQ Frequency Scale, only the RBQ Negative Scale was uniquely associated with clinically-relevant patterns of risky behaviors on the DIPD-IV. This suggests that negative reinforcement may be a more powerful motivational factor than positive reinforcement (or enhancement motives) for problematic levels of risky behaviors in SUD patients (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004). Future research is needed to clarify the precise role of both negative and positive reinforcement in a wide range of risky behaviors among SUD patients.

Finally, it is worth noting that the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales were strongly positively associated with one another, suggesting that they may be capturing (at least in part) a broad tendency to engage in risky behaviors in the context of emotional arousal (regardless of valence). Indeed, this finding is consistent with past research on the UPPS-P Positive and Negative Urgency Scales, which likewise indicates substantial overlap between these scales (with regard to their putative risk factors and underlying mechanisms) despite their distinct nature and differential relations to specific risky behaviors (Cyders & Smith, 2008). Additional research is needed to clarify the distinct and overlapping features of the tendency to engage in risky behaviors in the context of negative versus positive emotional arousal, as well as the extent to which the RBQ captures emotion-specific differences in emotion-driven risky behaviors or a broader tendency to engage in risky behaviors in the context of emotions in general.

Several limitations warrant mention. First, although the RBQ taps into the emotional antecedents of risky behaviors, it does not assess the emotional consequences of such behaviors. Thus, it remains unclear why SUD patients used risky behaviors when experiencing negative and positive emotions (e.g., to avoid, enhance, or maintain emotional experiences), and any conclusions regarding the function of the risky behaviors is speculative. Future investigations utilizing experience sampling methods may help elucidate the consequences of risky behaviors following negative and positive emotions. Second, the RBQ Negative and Positive Scales assess the role of emotional valence (i.e., negative versus positive) in risky behaviors, but not the roles of emotional intensity or specific negative and positive emotional states (e.g., shame, anger, excitement). Future research would benefit from clarifying the roles of specific emotions, as well as overall emotional valence and intensity, in risky behavior. Third, a comprehensive evaluation of the psychometric properties of this measure was not possible. Therefore, future research is needed to investigate other psychometric properties of this measure (e.g., test-retest reliability, predictive validity). For instance, our findings suggest gender and age differences on some of the RBQ Scales. Consistent with these results, past studies have found that (a) men (vs. women) report greater difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing positive emotions (Weiss, Gratz, & Lavender, 2015) and (b) younger (vs. older) adults exhibit greater deficits in impulse control (Steinberg, Graham, O’Brien, Woolard, Cauffman, & Banich, 2009). Research is needed to better understand why these differences exist, as well as to examine whether the factor structure of the RBQ and its relations to other relevant constructs differs as a function of age and gender. For instance, using IRT, investigators may test for differential item functioning, or whether individuals from different groups have a different probability of endorsing an item on a test, which may reflect measurement bias. Such research may speak to the utility of different norms for different populations (e.g., demographic or diagnostic groups). Finally, findings require replication across non-SUD clinical populations and more diverse non-clinical and community populations. For example, whereas positive emotional arousal may be particularly relevant to substance use among SUD patients, among other samples, substance use may be more likely be to driven by negative emotional arousal (i.e., self-medication).

Despite these limitations, results of the current study add to the literature on the emotion-dependent nature of risky behaviors, providing preliminary support for a comprehensive measure of the frequency and emotion-dependent nature of a variety of clinically-relevant risky behaviors and highlighting the differential relevance of negative and positive emotions to specific risky behaviors.

Appendix A

The Risky Behavior Questionnaire

Contributor Information

Nicole H. Weiss, Yale University School of Medicine, 389 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, CT 06511

Matthew T. Tull, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216

Katherine Dixon-Gordon, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 135 Hicks Way, Amherst, MA 01003-9271

Kim L. Gratz, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216

References

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Ellard KK, Fairholme CP, Farchione TJ, Boisseau CL, May JTE, Allen LB. Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Workbook. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A. The role of emotion in decision-making: Evidence from neurological patients with orbitofrontal damage. Brain and Cognition. 2004;55:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2003.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg JM, Latzman RD, Bliwise NG, Lilienfeld SO. Parsing the heterogeneity of impulsivity: A meta-analytic review of the behavioral implications of the UPPS for psychopathology. Psychological Assessment. 2015;27:1129–1146. doi: 10.1037/pas0000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum HG, White AG, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, Roland CL. Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse in the United States. Pain Medicine. 2011;12:657–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright WS. Costs of drug abuse to society. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 1999;2:133–134. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-176x(199909)2:3<133::aid-mhp53>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, White HR. Gender differences in adolescent and young adult predictors of intimate partner violence: A prospective study. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:1283–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, Cyders MA. Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol Use: A meta-analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:1441–1450. doi: 10.1111/acer.12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Flory K, Rainer S, Smith GT. The role of personality dispositions to risky behavior in predicting first-year college drinking. Addiction. 2009;104:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D Amico EJ, Edelen MO, Miles JNV, Morral AR. The longitudinal association between substance use and delinquency among high-risk youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue JJ, Goranson AC, McClure KS, Van Male LM. Emotion dysregulation, negative affect, and aggression: A moderated, multiple mediator analysis. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;70:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dreisbach G. How positive affect modulates cognitive control: The costs and benefits of reduced maintenance capability. Brain and Cognition. 2006;60:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreisbach G, Goschke T. How positive affect modulates cognitive control: Reduced perseveration at the cost of increased distractibility. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2004;30:343–353. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.30.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Sargent EM, Kilwein TM, Stevenson BL, Kuvaas NJ, Williams TJ. Alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences: Associations with emotion regulation difficulties. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40:125–130. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.877920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:509–528. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state:” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgas JP, Bower GH. Mood effects on person-perception judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:53–60. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry JD, Temkit M, Tu W, Graham CA, Katz BP, Orr DP. Daily mood, partner support, sexual interest, and sexual activity among adolescent women. Health Psychology. 2005;24:252–257. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Hasin DS. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Jung J, Hasin DS. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:39–47. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT, Levy R. Randomized controlled trial and uncontrolled 9-month follow-up of an adjunctive emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44:2099–2112. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, Watkins ER, Mansell W, Shafran R. Cognitive behavioural processes across psychological disorders: A transdiagnostic approach to research and treatment. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hien DA, First MB. The Drug Use Questionnaire. Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht M, Schmeichel BJ. What is ego depletion? Toward a mechanistic revision of the resource model of self-control. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2012;7:450–463. doi: 10.1177/1745691612454134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Simmons BL, Aklin WM, Daughters SB, Dvir S. Risk-taking propensity and risky sexual behavior of individuals in residential substance use treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1643–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:885–890. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Hope DA. Preliminary evaluation of a broadspectrum cognitive-behavioral group therapy for anxiety. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Pscychiatry. 2005;36:79–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patkar AA, Murray HW, Mannelli P, Gottheil E, Weinstein SP, Vergare MJ. Pre-treatment measures of impulsivity, aggression and sensation seeking are associated with treatment outcome for African-American cocaine-dependent patients. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2004;23:109–122. doi: 10.1300/J069v23n02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine SE, Wildes JE. Emotion dysregulation and symptoms of anorexia nervosa: The unique roles of lack of emotional awareness and impulse control difficulties when upset. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2013;46:713–720. doi: 10.1002/eat.22145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett-Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Dunbar GC. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P, Finucane ML, Peters E, MacGregor DG. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Analysis. 2004;24:311–322. doi: 10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Engel SG. Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:629–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology: Mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:124–135. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Graham S, O’Brien L, Woolard J, Cauffman E, Banich M. Age differences in future orientation and delay discounting. Child Development. 2009;80:28–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner DL. Being inconsistent about consistency: When coefficient alpha does and doesn't matter. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2003;80:217–222. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA8003_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Gratz KL, Lavender J. Factor structure and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of difficulties in the regulation of positive emotions: The DERS-Positive. Behavior Modification. 2015;39:431–453. doi: 10.1177/0145445514566504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Shinar O, Yaeger A. Contributions of positive and negative affect to adolescent substance use: Test of a bidimensional model in a longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:327–338. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Sickel AE, Young L. Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders. Boston, MA: McLean Hospital; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, McGlashan TH. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Reliability of axis I and II diagnoses. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2000;14:291–299. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]