Abstract

Objectives

This cross-sectional community based study was conducted to estimate the prevalence of consumption habits for non tobacco pan masala (ASU) and the risk of developing oral precancer in North India.

Methods

This study was conducted in the old town of Lucknow city in the state of Uttar Pradesh in India. Subjects residing for more than 6 months and aged 15 years or above, were enrolled in the study after their informed consent. A two page survey tool was used to collect the data. A three times more matched sample of non users was randomly obtained from this data to analyze and compare the final results.

Results

0.45 million subjects were surveyed. Majority of tobacco users were in the age group of 20–35 years among males and 35–39 years among females. Consumption of non tobacco pan masala among males as well as females was most common in 15–19 years of age group. Prevalence of oral precancer (leukoplakia, submucous fibrosis, erythroplakia, lichen planus, smokers palate and verrucous hyperplasia) was 3.17% in non tobacco pan masala users and 12.22% in tobacco users. The odds of developing oral precancer in non tobacco pan masala users was 20.71 (18.79–22.82) and in tobacco users was 88.07 (84.02–92.31) at 95% confidence interval against non users of both.

Conclusion

The odds of developing oral precancer even with consumption of pan masala is high, even when it is consumed without tobacco. It is hence recommended to discourage this habit.

Keywords: Pan masala, Oral precancer, Potentially malignant disorder, Prevalence, Odds ratio

1. Introduction

The word ‘substance’ is referred as non-essential food ingredient that is generally addictive. Amongst the three cardinal substances abused by the mankind, tobacco is the biggest killer.1 Worldwide smoking practices are in vogue, but chewing tobacco with pan or pan masala is typical to the Indian sub-continent.2 Undoubtedly, there is sufficient evidence to implicate tobacco to oral cancer and precancer, but it is unknown if non tobacco pan masala is equally harmful.3 Today, a clandestine sale of non tobacco pan masala has eroded the society. It is detrimental to the national health, and may also have a direct causal relationship to oral precancer followed by oral cancer.4

This study was carried out as a community based cross-sectional study design with the aim to estimate the prevalence of oral precancer in North India and to calculate the risk imposed with use of non tobacco pan masala.

2. Methods

This taskforce project, aimed to study the direct risk imposition (odds ratio) in users of pan masala or areca nut substance (ASU), tobacco in any form (TU) and non users with no chewing habits (NU). A sample size of approximately 0.45 million population was planned for this survey in the densely populated area of Lucknow. All permanent residents (residing for more than 6 months in the study area) aged 15 years and above were eligible for recruitment in the study after their informed consent. Mentally challenged people and those who could not be enrolled even after 3 visits, were excluded. Institutional ethical clearance was obtained. In order to achieve the 0.4 million sample size, all households in the Cis Gomti region of Lucknow were visited by trained social workers and dental surgeons. Research quality was maintained with control of sampling and measurement bias. Strict quality control measures were followed. A pilot survey during the course of this study showed that 4% of the total adult population above the age of 15 years consumed AS.

A two page survey tool, written in English, was used to collect data through interview and oral examination. It had 5 sections; I: included demographic details, II: non-tobacco pan masala and tobacco (gutkha, smoking), III: dose and duration details, IV: oral health examination, V: clinical diagnosis of the oral mucosal lesion, if present. Kuppuswamy's SES Scale,5 based on education, occupation and monthly family income, was used to distribute the surveyed population into 5 grades, where upper grade (I) with a score range of 26–29, upper middle (II) to 16–25, lower middle (III) to 11–15, lower upper (IV) to 5–10 and lower (V) to less than 5.

The data collected was tabulated and standard statistical tools were applied for detailed analysis using SPSS-17 software and reports were generated. To improve representativeness of the samples for distribution and characteristics of the study, population was suitably weighted for age and sex adjustments. All quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± deviation. Prevalence rates were estimated along with 95% confidence interval for qualitative variables.

A total of 453,823 subjects were interviewed and orally examined. The data was checked for internal consistency through previously framed questions; and incomplete or missing data was removed to obtain a total of 402,669 survey data for evaluation.

3. Results

73% of the population surveyed were non users. Non-tobacco pan masala was consumed by approx. 3% population. In contrast, 24% of the population consumed tobacco products. Among the total males in the population, 60% were non users, 3% non tobacco pan masala users and 37% tobacco users. Similarly, 84% of all the females in the population were non users, 3% consumed non tobacco pan masala and 13% consumed tobacco.

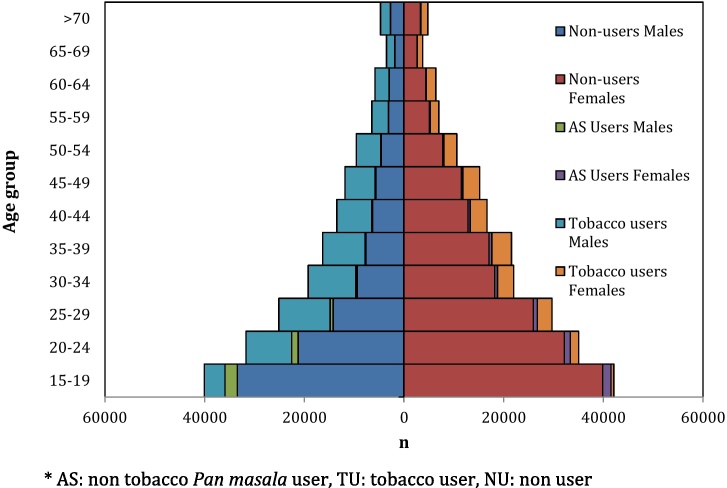

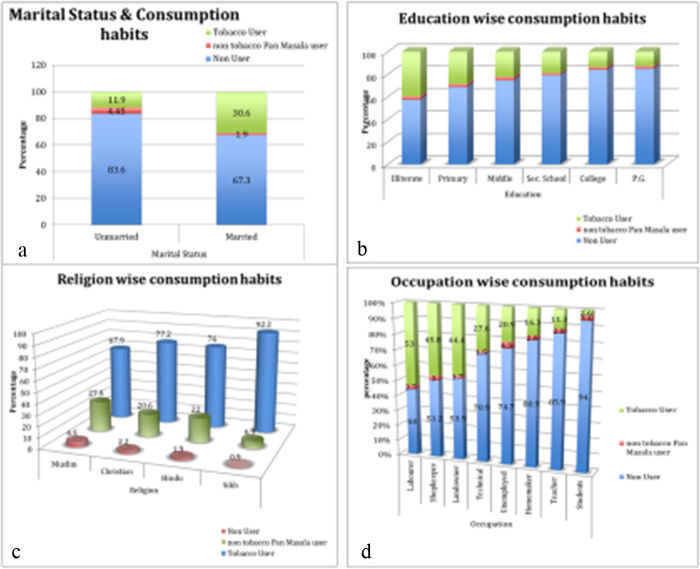

Consumption of non tobacco pan masala among males as well as females was most common in the 15–19 years of age group. Majority of tobacco users were in the age group of 20–35 years among males and 35–39 years among females (Fig. 1). Among the unmarried population, 4.45% were non tobacco pan masala users and 11.9% were tobacco users, whereas amongst the married subjects, 2% were non tobacco pan masala users and 30.6% were tobacco users (Fig. 2a). There was a definite trend of tobacco use with education level. The illiterate subjects consumed tobacco more than the literate ones (Fig. 2b). Tobacco as well as non tobacco consumption was more amongst the Muslims (Fig. 2c). While non tobacco pan masala was consumed more by the unemployed group, tobacco was much more practiced amongst the labourers (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 1.

Age-sex pyramid of the different types of users in the population. * AS: non tobacco pan masala user, TU: tobacco user, NU: non user.

Fig. 2.

(a–d) Marital status & consumption habits, education wise, religion wise and occupation wise distribution of the different types of users in the population. * AS: non tobacco pan masala user, TU: tobacco user, NU: non user.

A total of 12,711 cases of oral precancer (leukoplakia, erythroplakia, oral submucous fibrosis (SMF), verrucous hyperplasia, lichen planus and smokers palate) were clinically diagnosed in the population. Prevalence of oral precancer was 3.17% in non tobacco pan masala users, 12.22% in tobacco users and only 0.16% in non users (Table 1). Presentation of oral precancer in the population was 19 times more in non tobacco pan masala users, and 73 times more in tobacco users when compared with the non users.

Table 1.

Prevalence of oral precancer (leukoplakia, SMF, erythroplakia, verrucous hyperplasia, lichen planus and smokers palate).

| Prevalence | Non user 293,869 |

Non tobacco pan masala user 11,635 |

Tobacco user 97,165 |

Population 402,669 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukoplakia | 100 (0.03) | 69 (0.59) | 2811 (2.89) | 2980 (0.74) |

| SMF | 251 (0.09) | 277 (2.38) | 4683 (4.82) | 5211 (1.29) |

| Erythroplakia | 1 (0.00) | 1 (0.01) | 13 (0.01) | 15 (0.00) |

| Verrucous hyperplasia | 2 (0.00) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.01) | 7 (0) |

| Lichen planus | 24 (0.01) | 3 (0.03) | 54 (0.06) | 81 (0.0) |

| Smokers palate | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1900 (1.96) | 1900 (0.47) |

| Multiple lesions | 86 (0.03) | 19 (0.16) | 2412 (2.48) | 2517 (0.63) |

| Oral precancer | 464 (0.16) | 369 (3.17) | 11,878 (12.22) | 12,711 (3.16) |

Oral submucous fibrosis was the commonest oral precancer in the population, observed in 1.3% population (5211 cases in 402,669 subjects). 277 cases of SMF were observed in 11,635 non tobacco pan masala users (2.4%), 4683 in 97,165 tobacco users (4.8%), and 251 in 293,869 non users (0.1%). The second commonest oral precancer was leukoplakia, observed in 0.7% population (2980 cases in 402,669 subjects). 69 cases of leukoplakia were observed in 11,635 non tobacco pan masala chewers (0.6%), 2811 in 97,165 tobacco users (2.9%), and 100 in 293,869 non users (0.03%). Erythroplakia, verrucous hyperplasia, lichen planus and smokers palate were rarely seen in non tobacco pan masala users. Erythroplakia was observed in 0.004% in the population with only 15 cases diagnosed, of which only 1 among 11,635 non tobacco pan masala users.

The age, sex and SES study revealed that prevalence of oral precancer in non tobacco pan masala users increased up to 30 years of age and then declined, in contrast to in tobacco users. Precancer was more in males among non tobacco pan masala users, but more in females amongst tobacco users. Among non tobacco pan masala users, precancer was less in SES extreme grades, while among tobacco users, oral precancer increased with increased SES (Table 2). 4% male and 2% female non tobacco pan masala users developed oral precancer, while 14% male and 9% female tobacco users developed and 0.2% male and 0.1% female non users developed oral precancer (Table 2).

Table 2.

Age-sex wise prevalence of oral precancer (OP) in different users.

| S No. | Characteristics | Non user n = 293,869 (%) |

Non tobacco pan masala user n = 11,635 (%) |

Tobacco user n = 97,165 (%) |

All n = 402,669 (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age group (years) | 15–24 | 85 (0.07) n = 126,718 |

199 (3.01) n = 6620 |

1770 (11.34) n = 15,602 |

2054 (1.38) n = 148,940 |

| 25–39 | 202 (0.22) n = 92,495 |

117 (3.83) n = 3051 |

4745 (12.35) n = 38,416 |

5064 (3.78) n = 133,962 |

||

| ≥40 | 177 (0.24) n = 74,656 |

53 (2.70) n = 1964 |

5363 (12.43) n = 43,147 |

5593 (4.67) n = 119,767 |

||

| 2 | Sex | M | 263 (0.23) n = 113,015 |

228 (4.18) n = 5449 |

9489 (13.70) n = 69,240 |

9980 (5.32) n = 187,704 |

| F | 201 (0.11) n = 180,837 |

141 (2.28) n = 6186 |

2389 (8.56) n = 27,911 |

2731 (1.27) n = 214,934 |

||

| 3 | SES | Upper: I | 0 (0) n = 773 |

0 (0) n = 10 |

17 (7.00) n = 243 |

17 (1.66) n = 1026 |

| Upper middle: II | 25 (0.08) n = 31,253 |

29 (4.53) n = 640 |

478 (7.13) n = 6702 |

532 (1.38) n = 38,595 |

||

| Lower Middle: III | 127 (0.13) n = 94,283 |

101 (3.42) n = 2954 |

2409 (9.72) n = 24,791 |

2637 (2.16) n = 122,028 |

||

| Upper Lower: IV | 312 (0.19) n = 167,071 |

239 (2.99) n = 7996 |

8920 (13.69) n = 65,144 |

9471 (3.94) n = 240,211 |

||

| Lower: V | 0 (0) n = 489 |

0 (0) n = 35 |

54 (18.95) n = 285 |

54 (6.67) n = 809 |

||

The risk of developing oral precancer with non-tobacco pan masala use was (OR in non-tobacco pan masala users against non-users at 95% CI was 20.71 (18.79–22.82), i.e. almost one fourth of that for tobacco users, 88.07 (84.02–92.31). The odds of developing Leukoplakia in non tobacco pan masala users was 17.53 (14.02–21.91) at 95% CI against non users, and 34.83 (32.14–37.79) in tobacco users, which was almost 4 times more. The odds of developing SMF in non tobacco pan masala users was 28.53 (25.50–31.92) at 95% CI against non users, and 59.23 (55.24–63.52) in tobacco, which was again almost was 4 times more. The odds of developing oral erythroplakia in non tobacco pan masala users was 25.26 (3.95–161.36) at 95% CI against non users, and 39.32 (11.58–133.48) in tobacco users, almost 4 times more (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence and odds ratio of oral precancer.

| Prevalence n (%) |

Odds ratio (95% CI) vs non users | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall oral precancera | ||

| Non users n = 293,869 (%) |

464 (0.16) | |

| Non tobacco pan masala users n = 11,635 (%) |

369 (3.17) | 20.71 (18.79–22.82) |

| Tobacco users n = 97,165 (%) |

11,878 (12.22) | 88.07 (84.02–92.31) |

| All n = 402,669 (%) |

12,711 (3.16) | |

| Leukoplakia | ||

| Non users n = 293,869 (%) |

100 (0.03) | |

| Non tobacco pan masala users n = 11,635 (%) | 69 (0.59) | 17.53 (14.02–21.91) |

| Tobacco users n = 97,165 (%) |

2811 (2.89) | 34.83 (32.14–37.79) |

| All n = 402,669 (%) |

2980 (0.74) | |

| SMF | ||

| Non users n = 293,869 (%) |

251 (0.09) | |

| Non tobacco pan masala users n = 11,635 (%) | 277 (2.38) | 28.53 (25.50–31.92) |

| Tobacco users n = 97,165 (%) |

4683 (4.82) | 59.23 (55.24–63.52) |

| All n = 402,669 (%) |

5211 (1.29) | |

| Erythroplakia | ||

| Non users n = 293,869 (%) |

1 (0.00) | |

| Non tobacco pan masala users n = 11,635 (%) | 1 (0.01) | 25.26 (3.95–161.36) |

| Tobacco users n = 97,165 (%) |

13 (0.01) | 39.32 (11.58–133.48) |

| All n = 402,669 (%) |

15 (0.00) | |

6 oral precancer lesions included leukoplakia, SMF, erythroplakia, verrucous hyperplasia, lichen planus and smokers palate.

The results from this study show the risks associated with the non tobacco pan masala consumption and the odds to develop oral precancer. This study establishes that the harmful effects of non tobacco pan masala consumption are at par with tobacco users as it may equally lead to occurrence of oral precancer like leukoplakia and oral sub mucous fibrosis.

4. Discussion

Areca nut has been used commonly in Asia Pacific region and is socially acceptable among all sectors of the society including women, owing to its ceremonial values.6 Areca nut, usually incorporated in betel quid or Pan, is the fourth most common psychoactive substance in the world (after caffeine, alcohol and nicotine) and is used by several hundred million people.7, 8 In 1960, a set of house to house surveys in India of over 50,000 individuals 15 years and above in 5 districts of 4 states (Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat and Kerala) showed a range of betel quid usage prevalence of 3.3–37%.7 In other survey reported from India (Karnataka, Maharashtra), and some neighbouring countries like Nepal and Pakistan (Karachi) over last two and half decades,9 20–40% of population above 15 years were betel quid or areca nut users. In Ernakulam, Kerala, the highest prevalence of areca usage was found in 1960s, late 1970s and early 1980s. Over 30% of men and women aged 15 and above chewed betel quid, almost always used it with tobacco.7

A survey in Mumbai, 1992–94, among 99,598 residents 35 years and above, showed 57.5% men used tobacco, mostly in smokeless form. Areca nut was practiced by 29.7% of women and 37.8% of men but almost all with tobacco. Education level was inversely associated with tobacco use except cigarette smoking.10, 11, 12, 13

A community-based survey was conducted in two of the 168 villages of Sriperambudur Taluk in 2006 and 500 residents were selected by random sampling method. 19.8% were found to chew areca nut products, of which 11.2% indulged in chewing habit alone for areca nut products; 8.6% had multiple habits.14, 15 In a large survey in Uttar Pradesh, 10.6% of urban and 7.9% of rural males (>10 years) reported using gutkha or tobacco pan masala (80% of users <40 years), but fewer than 4% of these used pan masala without tobacco.16

A cross sectional retrospective case record study of oral cancer patients during 1991–2000 in Karnataka17 reported that 75% of oral cancer patients had risk habits. Majority 59% were chewers, but chewers of betel quid alone were 17%. In Taiwan,41 habit of chewing green unripe areca nut of the size of an olive, was more common among men than women (9.8% vs 1.6%). Another study in 1995 in 1110 residents of 2 states, 5–74 years, found that 72% males and 80% females chewed areca nut, 80% of whom incorporated tobacco in their quid.18

In a house to house survey of 22,000 villagers, aged 15 and above in Bhavnagar district, Gujarat,7 India 20.4% of males used mawa or betel quid. The popularity of areca nut mixtures, like mawa, pan masala, gutkha spawned an epidemic of SMF. Over 70% cases of SMF were under 35 years in 3 case–control studies in Gujarat, Maharashtra and New Delhi. Pan masala and gutkha chewers developed SMF in half the time as betel quid or areca nut chewers.19, 20 7.5% of pan masala chewers developed the disease within 4.5 years and quid chewers in 9.5 years.21

We observed a consumption of non tobacco pan masala by 3% population whereas tobacco was consumed 8 times more i.e. by 24% population. 4% of the younger population in the age group of 15–24 years consumed non tobacco pan masala, while tobacco was used by 10% of this age group. Consumption of non tobacco pan masala declined with advancement of age. 3% of the total males in the population and an equivalent percentage of females consumed non tobacco pan masala. In a study in Cambodia, most users were elderly women, 32.6% of women and 0.8% of men over 15 years chewed betel quid.22

We observed 3.16% of oral precancer in a house to house survey of 0.45 million population, which was quite similar to the observation made by Saraswathi23 of being around 4% in a hospital based study. Prevalence of oral precancer in our study was 3.17% in non tobacco pan masala users, but 12.22% in tobacco users, and only 0.16% in non users. This demonstrates the risks of oral precancer associated with these habits.

Higher SES index, education and income were found to be associated with decreased risk of oral premalignant lesions.24 We too observed that among non tobacco pan masala users, oral precancer declined with increased SES, but among tobacco users, it peaked with increased SES.

The prevalence rates for non tobacco pan masala consumption in India have not been evaluated earlier. However, the age adjusted prevalence rates of tobacco consumption in GATS-India25 showed that more than one-third (35%) of Indian residents use tobacco as smoking or smokeless forms. The prevalence was estimated to be much higher at 38% in rural areas as compared to 25% in urban areas with male predominance. The NFHS Survey26, 27 estimated the national tobacco use prevalence at 30% with male predominance (46.5%); highest in the group above 65 years amongst females (4%); and in the age group of 25–44 years amongst males (12%).

We observed that approx. 3% of non tobacco pan masala users in the different age groups presented with oral precancer, while 0.1–0.2% of non users and 11–12% tobacco users presented oral precancer.

Leukoplakia has been the most commonly seen oral precancer and has received the major attention, whether dysplasia is present or not. The global prevalence of leukoplakia is estimated to be between 1.7 and 2.7%10 or as 2 and 5% worldwide.28 In Sri Lanka, the prevalence of oral leukoplakia has been reported as 26.2 per 1000, respectively29 and in Italy, 16 (13.6%) among 118 randomly selected male population.30 A Swedish study indicated 0.1% of 15–24 year old persons had idiopathic leukoplakia and 0.8% had tobacco-associated leukoplakia.31 Prevalence of leukoplakia and mucosal disease in regular smokeless tobacco users ranged from 8 to 43%.32 In a study of 181,388 army inductees, Knapp reported leukoplakia in 0.024% of 18–25-year old men.33 Bouquot and Gorlin34 reported 0.8% oral leukoplakia among 23,616 white 20–29 year old men examined at University of Minnesota School of Dentistry. They also reported “tobacco/snuff pouch keratosis” in 4.3% of the entire male population. We observed the prevalence of Leukoplakia as 0.74% in North India, while others reported 0.54% in South India.35 These values depict that the prevalence of Leukoplakia is on the decline. Probably with the more and more usage of non tobacco areca nut substances, its prevalence has decreased in this decade in our country.

SMF is most commonly seen in Southeast Asia; with a prevalence ranging from 0.04 to 24.4%.36, 37, 38 In Sri Lanka, the prevalence is reported as 4.0 per 1000, respectively.29 High prevalence is seen in populations of the Indian subcontinent, affecting persons of all ages and both genders. Literature reports SMF in 0.36% in Ernakulum, Kerala, 0.31% in Trivandrum, 0.04% in Andhra Pradesh and 0.16% in Gujarat.39 A hospital based survey in cities namely Lucknow, Bombay, Bangalore and Trivandrum recorded prevalence of SMF as 0.51, 0.50, 0.18 and 1.22% respectively.38 While it has been reported as only 0.55% in the South India, we report 1.3% prevalence in North India.

Various non tobacco areca nut production companies have their manufacturing near Lucknow, so this area is a heavy consumption zone and may be the reason for the increased prevalence of SMF in this region. Promoted by a slick, high profile advertising campaign and aggressive marketing, pan masala and gutkha have become very popular in India. These products are typically consumed throughout the day. A number of small surveys conducted in schools and colleges in several states of India have shown that 13 ± 50% of students chew pan masala and gutkha on a regular basis.7

Odds ratio of oral precancer as observed in slum dwellers of Delhi in 2010 was 86.78 (95% CI: 10.57–712.24) for tobacco chewers, 38.73 (95% CI: 3.71–4.04) for those chewing betel nut and 53.25 (95% CI: 6.45–439.58).40 We observed an odds ratio for oral precancer of 20.71 (18.79–22.82) in non tobacco pan masala users and 88.07 (84.02–92.31) when we included leukoplakia, SMF, erythroplakia, verrucous hyperplasia, lichen planus and smokers palate as oral precancer. In a study by Jacob,40 2004, OR for leukoplakia was 12.8 (1.62–101.2) in areca nut users and 30.9 (13.7–69.7) in tobacco users. We observed an odds ratio of 17.53 (14.02–21.91) in non tobacco pan masala users and 34.83 (32.14–37.79). Jacob41 observed an OR of 148.9 (17.9–) for SMF in tobacco users. We observed an odds ratio for oral SMF at 95% confidence interval of 28.53 (25.50–31.92) in non tobacco pan masala users and 59.23 (55.24–63.52) in tobacco users against non users Jacob41 observed an OR of 96.0 (1.3–814.1–) for erythroplakia in tobacco users. We observed an odds ratio for erythroplakia at 95% confidence interval of 25.26 (3.95–161.36) in non tobacco pan masala users and 39.32 (11.58–133.48) in tobacco users against non users.

5. Conclusion

The prevalence of oral submucous fibrosis has tremendously increased. Leukoplakia, which was once believed to be the most common oral potentially malignant disorder, has now been outnumbered by SMF. The odds of developing oral precancer with non tobacco pan masala consumption habit are twenty times more than in non users.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgements

All participants of the study are acknowledged for allowing us to conduct the survey. Indian Council of Medical Research, India is acknowledged for funding the study (ICMR 5/13/3/TF-09-NCD III), without which this study would not have been possible.

References

- 1.Goodman J. Routledge; 2005, August 4. Tobacco in History: The Cultures of Dependence. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali I., Wani W.A., Saleem K. Cancer scenario in India with future perspectives. Can Ther. 2011;8(1):56–70. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta P.C., Murti P.R., Bhonsle R.B. Epidemiology of cancer by tobacco products and the significance of TSNA. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1996;26(2):183–198. doi: 10.3109/10408449609017930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llewellyn C.D., Johnson N.W., Warnakulasuriya K.A. Risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity in young people—a comprehensive literature review. Oral Oncol. 2001;37(5):401–418. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra D., Singh H.P. Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic status scale—a revision. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70(3):273–274. doi: 10.1007/BF02725598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pratt S. The challenge of betel nut consumption to economic development: a case of Honiara, Solomon Islands. Asia-Pac Dev J. 2014;21(2):103–120. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta P.C., Ray C.S. Epidemiology of betel quid usage. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2004;33:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhat S.J., Blank M.D., Balster R.L., Nichter M., Nichter M. Areca nut dependence among chewers in a South Indian community who do not also use tobacco. Addiction. 2010;105(7):1303–1310. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02952.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddy K.S., Gupta P.C. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; New Delhi: 2004. Tobacco Control in India; pp. 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van der Waal I. Potentially malignant disorders of the oral and oropharyngeal mucosa; present concepts of management. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(6):423–425. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta P.C. Survey of socio-demographic characteristics of tobacco use among 99,598 individuals in Bombay, India using handheld computers. Tob Control. 1996;5(2):114–120. doi: 10.1136/tc.5.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer . IARC; 2004. Betel-quid and Areca-nut Chewing and Some Areca-nut-derived Nitrosamines. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta P.C., Ray C.S. Tobacco, education & health. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126(4):289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajan G., Ramesh S., Sankaralingam S. Areca nut use in rural Tamil Nadu: a growing threat. Indian J Med Sci. 2007;61(6):332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray C.S., Gupta P.C. Bidis and smokeless tobacco. Curr Sci. 2009;96(10):1324–1333. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aruna D.S., Rajesh G., Mohanty V.R. Insights into pictorial health warnings on tobacco product packages marketed in Uttar Pradesh, India. Asia Pac J Can Prev. 2010;11:539–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aruna D.S., Prasad K.V., Shavi G.R., Ariga J., Rajesh G., Krishna M. Retrospective study on risk habits among oral cancer patients in Karnataka Cancer Therapy and Research Institute, Hubli, India. Asia Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(6):1561–1566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta P.C., Ray C.S. Smokeless tobacco and health in India and South Asia. Respirology. 2003;8(4):419–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldenberg D., Lee J., Koch W.M. Habitual risk factors for head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2004;131(6):986–993. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar S. Pan masala chewing induces deterioration in oral health and its implications in carcinogenesis. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2008;18(9):665–677. doi: 10.1080/15376510701738447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Priebe S.L., Aleksejūnienė J., Zed C. Oral squamous cell carcinoma and cultural oral risk habits in Vietnam. Int J Dent Hyg. 2010;8(3):159–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2010.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda N., Handa Y., Khim S.P. Prevalence study of oral mucosal lesions in a selected Cambodian population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1995;23(1):49–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1995.tb00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saraswathi T.R., Ranganathan K., Shanmugam S., Sowmya R., Narasimhan P.D., Gunaseelan R. Prevalence of oral lesions in relation to habits: cross-sectional study in South India. Indian J Dent Res. 2006;17(3):121–125. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.29877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashibe M., Jacob B.J., Thomas G. Socioeconomic status, lifestyle factors and oral premalignant lesions. Oral Oncol. 2003;39:664–671. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Natarajan E., Eisenberg E. Contemporary concepts in the diagnosis of oral cancer and precancer. Dent Clin N Am. 2011;255:63–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warnakulasuriya S., Johnson N.W., van der Waal I. Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:575–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Napier S.S., Speight P.M. Natural history of potentially malignant oral lesions and conditions: an overview of the literature. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillenwater A.M., Vigneswaran N., Fatani H., Saintigny P., El-Naggar A.K. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: a review of an elusive pathologic entity. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20(6):416–423. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3182a92df1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Health . 2009. National Oral Health Survey. Sri Lanka. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campisi G., Margiotta V. Oral mucosal lesions and risk habits among men in an Italian study population. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30(1):22–28. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.300104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Axell T. Occurrence of leukoplakia and some other oral white lesions among 20,333 adult Swedish people. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1987;15:46–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1987.tb00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greer R.O., Jr., Paulson T.C. Oral tissue alterations associate with the use of smokeless tobacco by teenagers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;56:275–284. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(83)90009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knapp M.J. Oral disease in 181,338 consecutive oral examinations. J Am Dent Assoc. 1971;83:1288–1293. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1971.0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouquot J.E., Gorlin R.J. Leukoplakia, lichen planus, and other oral keratoses in 23,616 white Americans over the age of 35 years. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61:373–381. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ranganathan K., Umadevi M., Saraswathi T.R., Kumarasamy N., Solomon S., Johnson N. Oral lesions and conditions associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection in 1000 South Indian patients. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2004;33:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Y.H., Lee H.Y., Tung S., Shieh T.Y. Epidemiological survey of oral submucous fibrosis and leukoplakia in aborigines of Taiwan. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:213–219. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.300404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Wyk C.W., Staz J., Farman A. The prevalence of oral mucosal lesions among a random sample of Asian residents in Cape Town. J Dent Assoc S Afr. 1977;32:589–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pindborg J.J., Mehta F.S., Gupta P.C. Prevalence of oral submucous fibrosis among 50,915 Indian villagers. Br J Cancer. 1968;22:646–654. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1968.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta P.C., Metha F.S., Daftary D. Incidence rates of oral cancer and natural history of oral precancerous lesions in a10-year follow-up study of Indian Villagers. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1980;8:287–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1980.tb01302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goel A., Goel P., Mishra S., Saha R., Torwane N.A. Risk factor analysis for oral precancer among slum dwellers in Delhi, India. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4(3):S218–S222. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.141962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacob B.J., Straif K., Thomas G. Betel quid without tobacco as a risk factor for oral precancers. Oral Oncol. 2004;40:697–704. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]