Summary

Given the possible importance of anti‐citrullinated peptide/protein antibodies (ACPA) for initiation and progression of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), extended knowledge about the different isotypes and subclasses is important. In the present study, we analysed the immunoglobulin (Ig)G subclasses regarding reactivity against cyclic citrullinated peptides (anti‐CCP) among 504 clinically well‐characterized patients with recent‐onset RA in relation to smoking habits, shared epitope (SE) status and IgA and pan‐IgG anti‐CCP antibodies. All patients, regardless of pan‐IgG anti‐CCP status, were analysed for IgG1–4 CCP reactivity. Sixty‐nine per cent were positive in any IgG anti‐CCP subclass, and of these 67% tested positive regarding IgG1, 35% IgG2, 32% IgG3, and 59% IgG4 anti‐CCP. Among ever‐smokers the percentages of IgG2 anti‐CCP (P = 0·01) and IgA anti‐CCP (P = 0·002)‐positive cases were significantly higher compared to never‐smokers. A positive IgG anti‐CCP subclass ‐negative cases. Combining SE and smoking data revealed that IgG1 and IgG4 anti‐CCP were the IgG anti‐CCP isotypes associated with expression of SE, although the lower number of patients positive for IgG2 or IgG3 anti‐CCP could, however, have influenced the results. High levels of IgG2 anti‐CCP were shown to correlate with expression of the ‘non‐SE’ allele human leucocyte antigen (HLA)‐DRB1*15. In conclusion, in this study we describe different risk factor characteristics across the IgG anti‐CCP subclasses, where IgG2 appears similar to IgA anti‐CCP regarding the predominant association with smoking, while IgG1 and IgG4 related more distinctly to the carriage of SE genes.

Keywords: cyclic citrullinated peptide, IgG subclasses, rheumatoid arthritis, shared epitope, smoking

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common chronic inflammatory disease, subdivided into rheumatoid factor (RF) and/or anti‐citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)‐positive and RF/ACPA‐negative cases 1. Although not stipulated in the 1987 and 2010 RA classification criteria 2, 3, a positive RF test refers usually to immunoglobulin (Ig)M‐class antibodies against IgG‐Fc (human, rabbit, horse and a multitude of other species), whereas a positive ACPA test refers generally to IgG‐class antibodies. The majority of RF‐positive RA patients are also ACPA‐positive and vice versa, and these patients generally have a more severe disease course and outcome compared to the RF‐ and ACPA‐seronegative RA cases 4, 5, 6, 7. The most commonly used ACPA tests detect IgG‐class antibodies directed against ‘the 2nd generation cyclic citrullinated peptide’ (CCP2) 8.

It is well known that cigarette smoking 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and genetic carriage of human leucocyte antigen (HLA)‐DR/‘shared epitope’ (SE) 15, 16 are risk factors for RA development, and that the combination of SE carriage and smoking increases markedly the risk of developing ACPA‐positive RA 17, 18, 19, 20. Apart from HLA‐DRB1/SE, the ‘non‐SE’ allele HLA‐DRB1*15 has also been indicated to promote high levels of ACPA 21.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells from smokers display more extensive protein‐citrullination compared to BAL cells from non‐smokers 18, due presumably to the excessive cell damage following the exposure of toxic contents from cigarettes. In patients with recent‐onset RA, the occurrence of circulating IgG anti‐CCP was shown to associate with parenchymal lung abnormalities and site‐specific citrullination, and antibodies (IgG‐ and IgA‐RF as well as IgG anti‐CCP) were enriched in the lungs 22. We have shown recently that cigarette smoking associates with circulating IgA anti‐CCP in RA, but not with IgG anti‐CCP 23.

The dynamics and consequences of IgG responses relate to the degree of T cell dependency, IgG subclass predominance, Fc‐gamma receptor (FcγR) affinity and FcγR‐mediated cell activation/inhibition 24. IgG subclasses 1–3 all have cell‐activating properties after ligating FcγRI, IIA IIIA or IIΙB exposed on cell surfaces, whereas IgG1 has a down‐regulating/inhibitory effect after ligation to cell surface FcγRIIB [24]. Depending on the circumstances, IgA‐class antibodies can exert dual effects after ligation to cell‐surface FcRs, and can thus be both pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory 25. In contrast to IgG‐class antibodies, IgA does not activate complement via the classical pathway 26. Like IgA, IgG4 can exert anti‐inflammatory effects due to its unique bi‐antigen recognition after undergoing Fab‐arm exchange 27. The anti‐inflammatory effect of IgG4 has been suggested to be due to limitation of immune complex formation 27.

Total IgG anti‐CCP is analysed in clinical praxis, whereas IgM and IgA anti‐CCP antibodies are usually not 28, 29. We have shown previously that the presence of circulating IgA antibodies to citrullinated antigens, in combination with high‐level IgG‐ACPA, is more common in recent‐onset RA patients with a severe disease course compared to patients with IgG‐class antibodies alone 28, 30. Others have shown that the presence of IgA anti‐CCP at high levels increases the risk of developing RA among patients with undifferentiated arthritis 29.

The present study was undertaken to shed light upon the different IgG anti‐CCP subclasses in recent‐onset RA in relation to cigarette smoking, SE and IgA anti‐CCP.

Materials and methods

Subjects

A total of 504 clinically well‐characterized patients with recent‐onset RA (< 12 months since first observed joint‐swelling, according to the patients’ judgement) were recruited to the Swedish TIRA‐2 inception cohort (Swedish acronym for ‘Early Intervention in Rheumatoid Arthritis’) 2006–09, based on:

-

(a)

fulfilment of ≥ 4/7 criteria according to the American College of Rheumatology 1987 revised RA‐classification criteria (ACR‐87) 3 (n = 422);

-

(b)

morning stiffness ≥ 60 min, symmetrical arthritis and arthritis of hands (wrists, metacarpophalangeal or proximal interphalangeal joints) or feet (metatarsophalangeal joints); (n = 23); or

-

(c)

≥ 1 swollen joint and a positive test for IgG anti‐CCP positivity (n = 59).

Patient characteristics at inclusion are summarized in Table 1. The patients had not received disease‐modifying anti‐rheumatic drugs or corticosteroids prior to the initial blood sampling at the first visit. Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) blood and serum samples were taken from all participants and stored at −70°C until analysed.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 504 TIRA‐2 patients at inclusion

| Smoker | SE | HLA‐DRB1*15 | Pan‐IgG anti‐CCP | IgA anti‐CCP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Ever | Never | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | |

| Patients (n, %) | 504 | 168 (64) | 95 (36) | 370 (74) | 132 (26) | 106 (21) | 396 (79) | 349 (70) | 148 (30) | 130 (26) | 367 (74) |

| Age median (years) | 60 | 60 | 54 | 60 | 61 | 61.5 | 60 | 60 | 61 | 60 | 59 |

| Age range (years) | 18–89 | 21–79 | 18–82 | 18–87 | 19–89 | 20–87 | 18–89 | 18–87 | 19–89 | 18–86 | 17–89 |

| Female (n, %) | 339 (67) | 119 (71) | 72 (76) | 248 (67) | 89 (67) | 72 (68) | 265 (67) | 240 (69) | 93 (63) | 82 (63) | 251 (68) |

| Male (n, %) | 165 (33) | 49 (29) | 23 (24) | 122 (33) | 43 (33) | 34 (32) | 131 (33) | 109 (31) | 55 (37) | 48 (37) | 116 (32) |

TIRA‐2 = Swedish acronym for ‘Early Intervention in Rheumatoid Arthritis’; SE = shared epitope; + = positive; − = negative; anti‐CCP = anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide; HLA = human leucocyte antigen; Ig = immunoglobulin.

Serum samples from 101 healthy blood donors, 51 women and 50 men, served as controls for the antibody analyses.

Smoking habits

Data on cigarette smoking habits (prior to the first symptoms of arthritis) were available for 263 of the RA patients. Fifty‐seven emanated from medical records of RA patients included at the Falun hospital. The remaining 206 TIRA‐2 RA cases participated in the Stockholm‐based ‘Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis’ (EIRA) project (Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden), where smoking habits were available from questionnaires 18. The smoking data were categorized into ever‐smokers (current and former smokers) and never‐smokers.

Genetic analyses

DNA was extracted from EDTA blood samples collected at inclusion, using the Maxwell 16 blood DNA purification kit (Promega GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Sequencing for the whole of HLA‐DRB1 was carried out using Sanger Sequencing (BGI Europe, Shenzhen, China). DNA for genotyping was available for 502 of the patients. Patients carrying one or two alleles of HLA‐DRB1*01, *0401, *0404, *0405, *0408, *0409, *0410, *0413, *0416, *0419, *0421 or *10 were regarded as SE carriers (SE+) and the remainder as non‐SE carriers (SE–). In addition to SE alleles, non‐SE alleles were also analysed, but only HLA‐DRB1*15 reached a large enough frequency to allow statistical calculations. Carriers of HLA‐DRB1*15 were denoted HLA‐DRB1*15+ and non‐carriers HLA‐DRB1*15–.

IgG anti‐CCP subclass analyses

The levels of IgG anti‐CCP subclasses were measured in all patients, regardless of pan‐IgG anti‐CCP status, using an in‐house‐modified enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Euro‐Diagnostica, Malmö, Sweden). Serum samples were diluted 1 : 50, added to CCP‐coated microtitre plates and incubated for 1 h. Following washing, a monoclonal mouse anti‐human antibody specific for the respective IgG subclass was used: IgG1, 2 and 4 from AbD Serotec (Kidlington, UK; IgG1 clone 2C11; IgG2 clone 3C7 and IgG4 clone HP 6023). Antibodies against IgG3 (clone NI 86; HP 6080) were obtained from Nordic Immunology (Eindhoven, the Netherlands). The monoclonal antibody preparations were in‐house titrated and regarded optimal at the following dilutions: 1 : 2000 for IgG1, 1 : 5000 for IgG2 and 1 : 10 000 for IgG3 and IgG4, respectively. Alkaline‐phosphatase‐conjugated polyclonal rabbit anti‐mouse immunoglobulins were used as detection antibody (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), p‐nitrophenol phosphate solution as substrate solution (AbD Serotec) and 1 M NaOH as stop solution. The plates were read at 405 nm, with 650 nm as reference wavelength (TECAN Sunrise, software: Magellan version 7.1; Tecan Nordic AB, Mölndal, Sweden). A seven‐step serial dilution of known high‐level IgG anti‐CCP patient sera for the respective IgG subclass was used for standard curve calculations. IgG anti‐CCP subclass data were available from 504 patients. Serum samples were analysed in duplicate and the cut‐off limit for positivity was set at the 99th percentile of the 101 healthy blood donor control sera (cut‐off: IgG1 5339 U/ml, IgG2 3759 U/ml, IgG3 7818 U/ml and IgG4 2080 U/ml).

IgA and pan‐IgG anti‐CCP analyses

IgA and pan‐IgG anti‐CCP were analysed in baseline serum samples by means of fluoroenzyme‐immunoassay [EliATM; Thermo Fisher Scientific (PhaDia AB, Uppsala, Sweden)]. The cut‐off level for a positive IgA and pan‐IgG anti‐CCP test was set at the 99th percentile (cut‐off IgA: 1·6 U/ml, pan‐IgG: 7 U/ml) of the 101 healthy blood donor control sera. IgA and pan‐IgG anti‐CCP data were available from 497 patients. All but nine of the IgA‐positive patients were positive in ≥ 1 anti‐CCP IgG subclass. Six patients were positive in pan‐IgG anti‐CCP but not in any of the IgG subclasses, and six patients were negative in pan‐IgG anti‐CCP but positive in any of the IgG subclasses.

RF analyses

Agglutinating RF tests were performed in a clinical routine setting at each local laboratory associated with the participating rheumatology unit.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism version 6 (Graphpad® Software Inc., version 6.0c, La Jolla, CA, USA) and spss (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). P‐values for differences in proportions of IgG anti‐CCP subclasses were calculated using the two‐tailed Fisher's exact test. Differences with a P‐value < 0·05 were regarded as significant. P‐values for differences in IgG anti‐CCP subclass levels were analysed in IgG anti‐CCP‐positive cases using the Mann–Whitney test. Due to the high proportion of patient samples exceeding the highest standard point in pan‐IgG (44%) and IgG1 (46%), we used IgG2 (3%), IgG3 (9%), IgG4 (7%) and IgA (0%) to analyse correlations of HLA‐DRB1*15 and anti‐CCP levels. P‐values < 0·05 were regarded as significant. Two‐way analysis of variance (anova) was used to analyse interactions between SE and smoking habits and the levels of pan‐IgG, IgA and IgG subclass anti‐CCP in anti‐CCP‐positive and ‐negative patients. A P‐value < 0·05 was regarded as significant. The correlation between subclass usage and the levels of pan‐IgG anti‐CCP was analysed using Spearman's correlation coeffient. A P‐value < 0·05 was regarded as significant.

Ethics approval

The participating patients gave their written informed consent. The regional ethical review board in Linköping, Sweden approved the study protocol (decision number M168‐05).

Results

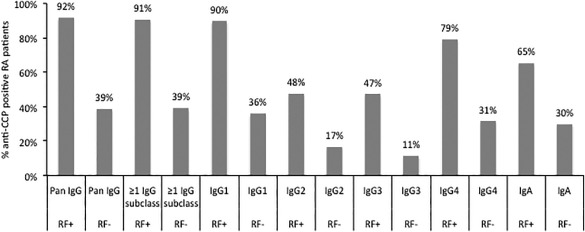

Distribution of IgG1‐4 anti‐CCP subclasses and IgA anti‐CCP

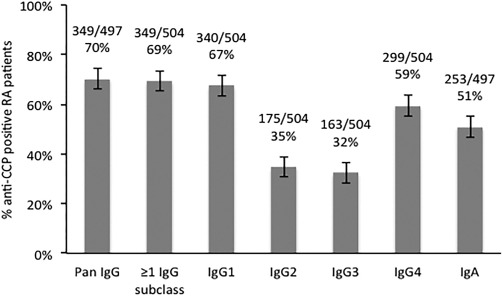

Of the 504 TIRA‐2 patients, 69% were positive in ≥ 1 of any anti‐CCP IgG subclass. For the respective subclass, 67% were IgG1‐positive, 35% IgG2‐positive, 32% IgG3‐positive and 59% IgG4‐positive (Fig. 1). This pattern (IgG1 > IgG4 > IgG2 ≈ IgG3) was seen generally throughout the study. Data on pan‐IgG anti‐CCP were available from 497 patients, and among these 69% were pan‐IgG anti‐CCP‐positive.

Figure 1.

The graph shows the percentages of immunoglobulin (Ig)G1–4 and IgA and pan‐IgG anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP)‐positive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients (subclasses n total = 504, IgA and pan‐IgG n total = 497) analysed by in‐house‐modified CCPlus enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Eurodiagnostica) (IgG1‐4 anti‐CCP) and PhaDia (IgA and pan‐IgG anti‐CCP). The cut‐off was set at the 99th percentile of 101 healthy blood donor control sera.

The overall IgG subclass repertoire, among the 69% patients testing positive in ≥ 1 of any IgG anti‐CCP subclass, revealed that 12% were positive in one subclass, 30% positive in two, 23% positive in three and 35% positive in all four (data not shown). A strong correlation was seen between the number of IgG subclasses present and the concentration of pan‐IgG anti‐CCP (r = 0·90, P < 0·0001). All patients testing positive in ≥ 2 IgG anti‐CCP subclasses were pan‐IgG‐positive and IgG1‐positive, and all except 12 were IgG4‐positive (data not shown).

Of 497 patients, 253 (51%) tested positive for IgA anti‐CCP antibodies (Fig. 1). All but nine of these IgA‐positive patients were also positive in ≥ 1 anti‐CCP IgG subclass, and all but 10 were pan‐IgG‐positive (data not shown). In the IgA‐positive patients IgG2 (P = 0·001) and IgG3 (P < 0·001) anti‐CCP were significantly more frequent than IgG1 and IgG4 anti‐CCP (data not shown).

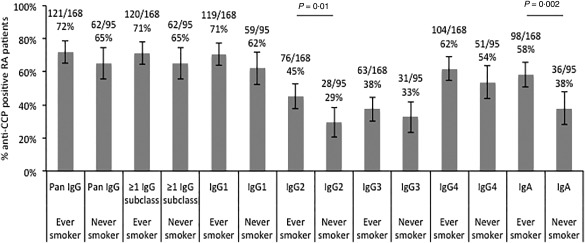

IgG anti‐CCP subclass and IgA anti‐CCP versus smoking

Among the 263 patients, with smoking data available, 69% tested positive for ≥ 1 IgG anti‐CCP subclass. Sixty‐four per cent were ever‐smokers and, of these, 72% were pan‐IgG anti‐CCP‐positive and 71% were positive in ≥ 1 IgG anti‐CCP subclass. Among the never‐smokers, 65% were pan‐IgG anti‐CCP‐positive and 65% tested positive for ≥ 1 IgG anti‐CCP subclasses (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Percentages of immunoglobulin (Ig)G1–4 and IgA and pan‐IgG anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP)‐positive cases among smoking and non‐smoking rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients (n total= 263) analysed by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and PhaDia (IgA and pan‐IgG anti‐CCP) (P‐values by Fisher's exact test).

When investigating IgG anti‐CCP subclasses separately, IgG1 anti‐CCP was the most frequent, followed by IgG4, IgG2 and IgG3 anti‐CCP in ever‐smoker as well as never‐smokers. However, the proportion of IgG2 anti‐CCP‐positive cases differed significantly between ever‐ and never‐smokers (P = 0·01). The fractions of IgG1, IgG3 and IgG4 anti‐CCP did not differ significantly between ever‐ and never‐smokers (Fig. 2).

IgA anti‐CCP‐positive cases were significantly more frequent among ever‐smokers compared to never‐smokers (P = 0·002) (Fig. 2).

IgG anti‐CCP subclass and IgA anti‐CCP versus SE and HLA‐DRB1*15

Data on SE status were available from 502 patients. Among the 370 patients that were SE carriers (SE+), 78% were pan‐IgG anti‐CCP‐positive and 77% tested positive for ≥ 1 IgG anti‐CCP subclass. Among the 132 SE‐negative (SE–) patients, 47% were pan‐IgG anti‐CCP‐positive and 47% were positive in ≥ 1 IgG anti‐CCP subclass (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Percentages of immunoglobulin (Ig)G1–4 and IgA and pan‐IgG anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP)‐positive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients expressing shared epitope (SE+) or not expressing (SE–) (n total= 502, P‐values by Fisher's exact test).

The proportion of IgG anti‐CCP‐positive cases in the SE+ subgroup was significantly higher compared to the SE– subgroup, regardless of subclass (P < 0·0001 for IgG1 and IgG4, P = 0·02 for IgG2 and P = 0·003 for IgG3). Taken together, a positive anti‐CCP subclass test in any of the IgG anti‐CCP subclasses was significantly more common in the SE+ group compared to the SE– cases (Fig. 3).

The same was seen regarding IgA‐class antibodies, where the fraction of anti‐CCP‐positive patients was higher within the SE+ subgroup compared to the SE– subgroup (P < 0·0001) (Fig. 3).

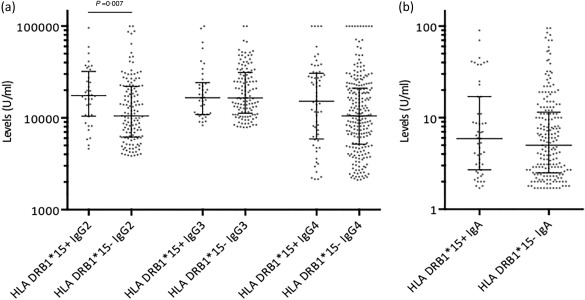

Data on HLA‐DRB1*15 were available from 502 patients, 106 of whom were carriers. The status regarding IgG anti‐CCP subclass distribution did not differ between HLA‐DRB1*15 carriers and non‐carriers. However, when comparing serum levels of IgG anti‐CCP antibody subclasses among patients testing positive in the respective IgG subclass, HLA‐DRB1*15 carriers showed higher average levels of IgG2 anti‐CCP (P = 0·007) (Fig. 4a). This was not seen for IgG3 anti‐CCP or IgA anti‐CCP, and only a trend was noted for IgG4 anti‐CCP (P = 0·07) (Fig. 4a,b). Pan‐IgG and IgG1 anti‐CCP levels were not analysed in relation to HLA‐DRB1*15 due to the high proportion of patient samples exceeding the highest standard point in the ELISA.

Figure 4.

Serum levels by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of immunoglobulin (Ig)G1–4 among rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients testing positive for the respective IgG anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) subclasses (a), and RA patients testing positive for IgA anti‐CCP (b) in relation to expression of human leucocyte antigen (HLA)‐DRB1*15 (HLA‐DRB1*15+) or no expression of HLA‐DRB1*15 (HLA‐DRB1*15–) (bars showing median with interquartile range. P‐values by Mann–Whitney test).

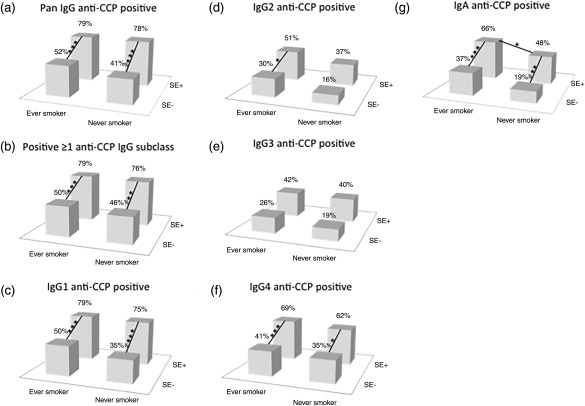

IgG anti‐CCP subclass and IgA anti‐CCP versus smoking and SE

Data on the combination of smoking habits and SE status were available from 262 patients, 121 of whom were SE+ ever‐smokers, 46 were SE– ever‐smokers, 63 were SE+ never‐smokers and 32 were SE– never‐smokers (data not shown).

Compared to SE– cases, the fraction of patients positive for SE+ and pan‐IgG anti‐CCP (Fig. 5a) or with ≥ 1 IgG anti‐CCP subclass (Fig. 5b) was larger both among ever‐smokers (P = 0·0009, P = 0·0004, respectively) and never‐smokers (P = 0·0005, P = 0·003, respectively).

Figure 5.

Pan‐immunoglobulin (Ig)G anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) (a), ≥ 1 IgG subclass (b), IgG1 (c), IgG2 (d), IgG3 (e), IgG4 (f) and IgA (g) anti‐CCP positivity in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients, ever‐smokers and never‐smokers combined with carriers and non‐carriers of shared epitope (SE) (n total= 262). Columns show the proportions of positive tests (> 99th percentile). *Statistical significance between the different patient groups (*≤ 0·05; **≤ 0·01; ***≤ 0·001, P‐values by Fisher's exact test).

The fraction of IgG1 anti‐CCP‐positive cases among SE+ patients was larger among ever‐smokers (P = 0·0005) and never‐smokers (P = 0·0007) compared to the SE– cases (Fig. 5c). The fraction of IgG2 anti‐CCP‐positive cases was higher among SE+ ever‐smokers compared to SE– ever‐smokers (P = 0·02). Interestingly, the SE+ subgroup showed a trend towards a higher fraction of IgG2 anti‐CCP‐positive cases among ever‐smokers compared to never‐smokers (P = 0·06). The same was seen when SE+ was compared to SE– among never‐smokers (P = 0·06) (Fig. 5e). The fraction of SE+ cases testing positive for IgG4 anti‐CCP was higher both among ever‐smokers (P = 0·001) and never‐smokers (P = 0·03) compared to the SE– negative cases (Fig. 5f).

The fraction of IgA anti‐CCP‐positive cases was significantly higher among SE+ compared to SE– cases regardless of smoking habits (P = 0·0008 for ever‐smokers and P = 0·007 for never‐smokers). A difference correlating with smoking habits was seen among SE+ cases, where ever‐smokers presented a higher proportion of IgA anti‐CCP‐positive cases compared to never‐ smokers (P = 0·02) (Fig. 5g).

The interaction between SE and smoking and the levels of the different anti‐CCP isotypes and subclasses were also analysed using anova, but no statistical significant difference could be shown (data not shown).

IgG anti‐CCP subclasses and RF

Of the 504 TIRA‐2 patients, 91% tested positive for ≥ 1 anti‐CCP IgG subclass as well as for RF. For the respective subclasses, 90% were IgG1‐ and RF‐positive, 48% IgG2‐ and RF‐positive, 47% IgG3‐ and RF‐positive and 79% IgG4‐ and RF‐positive. Data on IgA and pan‐IgG anti‐CCP were available from 497 patients, 65% of whom were IgA anti‐CCP‐ and RF‐positive and 92% were pan‐IgG anti‐CCP‐ and RF‐positive. All patients positive for RF were more frequently anti‐CCP‐positive regardless of isotype and subclass compared to RF‐negative patients (P < 0·0001) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

The graph shows the percentages of immunoglobulin (Ig)G1–4 and IgA and pan‐IgG anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP)‐positive cases (subclasses n total = 504, IgA and pan‐IgG n total = 497) among rheumatoid factor (RF)‐positive and RF‐negative rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients analysed by in house‐modified CCPlus enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Eurodiagnostica) (IgG1–4 anti‐CCP) and PhaDia (IgA and pan‐IgG anti‐CCP) and agglutination test (RF).

Discussion

Given the potential contribution of different ACPAs to the development and progression of RA, extended information about the different isotypes and IgG subclasses is important. In the present study we aimed to pin‐point usage of the four IgG subclasses among 504 recent‐onset RA patients in relation to smoking habits, SE status and circulating IgA anti‐CCP. We found that all IgG anti‐CCP subclasses associated with SE, but when smoking was taken into account only IgG1 and IgG4 anti‐CCP associated with SE. IgG2 anti‐CCP alone associated with smoking.

To identify serum anti‐CCP‐positive RA patients, we applied a strict cut‐off level at the 99th percentile among 101 blood donors, referring to anti‐CCP of all four IgG subclasses as well as to IgA anti‐CCP. As reported previously by Chapuy‐Regaud et al. 31 (anti‐citrullinated fibrin antibodies) and Verpoort et al. 29 (anti‐CCP), we confirmed that IgG4 anti‐CCP was almost as frequent (59%) as IgG1 (67%), whereas the occurrence rates of IgG2 (32%) and IgG3 (32%) anti‐CCP were considerably lower. Others have reported the presence of IgG1, IgG3 and IgG4 anti‐viral citrullinated peptide/histone citrullinated peptide in RA patients, while the presence of IgG2 anti‐viral citrullinated peptide/histone citrullinated peptide was negligible 32. The discrepancy between the present study and the study by Panza et al. could be due to the use of different antigens in the antibody analyses, or that the patients were in different stages of the disease. Circulating IgA anti‐CCP was recorded in 51% of the cases. However, the detection method does not allow direct comparisons of absolute serum levels of the different anti‐CCP antibody isotypes and subclasses.

Looking separately at IgG‐ and IgA‐ACPA in relation to SE and smoking habits, it is clear from previous research that IgG‐ACPA formation (without subclass specification) is associated with HLA‐DRB1/SE but not with cigarette smoking, whereas IgA‐ACPA relates to cigarette smoking but not to HLA‐DRB1/SE 23. In the current study we present evidence that the IgG anti‐CCP subclasses that associate with HLA‐DRB1/SE are IgG1 and IgG4 (Fig. 5). However, the low number of patients positive for SE and IgG2 or IgG3 anti‐CCP could have influenced the results. Furthermore, we found not only that IgA anti‐CCP but also IgG2 anti‐CCP antibodies were significantly more frequent among ever‐smoking RA patients compared to never‐smoking RA cases, and that this response might be independent of SE status (Fig. 5).

It has long been known that IgG2 antibodies against antigens with repeated antigenic determinants can stimulate B cells to induce antibodies without T helper (Th) cell co‐operation 33, a field currently experiencing renewed interest 34, 35, 36, 37. Hypothetically, this may indicate Th cell‐independent formation of IgG2‐ and/or IgA‐ACPA. Another hypothesis regarding the increase in IgG2 anti‐CCP is the potential involvement of the periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis in RA development. P. gingivalis expresses a citrullinating enzyme, porphyromonal peptidyl‐arginine deiminase (PPAD), which may increase the load of citrullinated antigens that could interfere with the host's immune functions 38. P. gingivalis has a broad range of virulence factors such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) 39 and, interestingly, the host's general immune response to LPS is secretion of IgG2 40. Also, the presence of P. gingivalis is more frequent in smokers 41, and thus one speculative explanation for the increased proportion of IgG2 anti‐CCP in RA smokers could be increased P. gingivalis infection. Indeed, Mikuls et al. found that IgG2 anti‐CCP, unlike the other subclasses, correlated with antibodies to P. gingivalis in RA patients 42.

The proportion of IgG anti‐CCP‐positive cases in the SE+ subgroup was significantly higher compared to the SE– subgroup regardless of IgG anti‐CCP subclass and anti‐CCP isotype. However, when we combined the data regarding SE and smoking and correlated it with the different IgG anti‐CCP subclass, we found an increased proportion of IgG4 anti‐CCP‐positive cases which was not associated with smoking (Fig. 5). IgG4 antibody production has been associated with prolonged and/or repeated antigen exposure 43. As antibodies to citrullinated antigens may be present long before symptom onset 44, it is likely that exposure to disease‐inducing antigens occurs for a long time, possibly explaining the high proportion of IgG4 anti‐CCP‐positive RA patients in our cohort. However, a contradiction to this is the fact that levels of IgG4 as well as other anti‐CCP isotypes and subclasses, apart from IgG1, have been reported to decline over time in RA patients 29. Speculatively, the high proportion of IgG4 anti‐CCP‐positive RA patients in our cohort could also represent an anti‐inflammatory response via Fab‐arm exchange effects 27.

Natural bi‐specific (IgG4 anti‐CCP and IgG anti‐RF) antibodies have actually been identified in RA patients 45. Natural bi‐specific antibodies are postulated not to burden inflammation due to the limited ability to activate complement, but instead be a beneficial event for the patients and perhaps be a potential indicator of disease remission 45. However, high levels of IgG4 antibodies have been shown to associate with higher disease activity and poor response to treatment 46 and IgG4 antibody may also have pathogenic properties, as seen in bullous pemphigoid 47.

HLA‐DRB1*15 is a non‐SE allele that has been associated with renal involvement in Japanese RA patients 48. The secondary form of Sjögren's syndrome in RA patients has also been shown to associate with an increased frequency of HLA‐DRB1*15 expression 49. More recently, Laki et al. 21 have shown that the HLA‐DRB1*15 is associated with high levels of IgG anti‐CCP. In the present study we found that, among IgG2 anti‐CCP‐positive cases, HLA‐DRB1*15 was associated with elevated levels of IgG2, again indicating the importance of genetic background for RA development. DERAA is another non‐SE allele, where its presence is related to lower susceptibility of RA development 50. This allele was found in our patient cohort, but the frequency was too low to justify any statistical calculations.

To conclude, in this cohort of well‐characterized early RA patients, we describe different risk factor characteristics across the IgG anti‐CCP subclasses. When we combined SE and smoking data and correlated these with IgG anti‐CCP subclass data, we found that IgG1 and IgG4 anti‐CCP associate with HLA‐DRB1/SE. In contrast, IgG2 and IgA anti‐CCP appear more dependent upon smoking. These findings further detail the contributions of genes and environment to citrulline‐related immune reactions in early RA.

Disclosure

There are no disclosures to report.

Author contributions

The study was designed by T. S. and K. M.; A. J. and K. M. performed the experiments and statistical analyses. T. S. and A. K. were responsible for patient samples and characterization. All authors were involved in analysing the data and writing the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank all TIRA co‐workers. This project was funded by grants from the Swedish Society of Medicine, The Swedish Research Council, Medical Research Council of Southeast Sweden, Reinhold Sund foundation, King Gustaf V's 80‐year foundation, the Swedish Rheumatism association and the Östergötland County Council.

References

- 1. Sun J, Zhang Y, Liu L, Liu G. Diagnostic accuracy of combined tests of anti cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody and rheumatoid factor for rheumatoid arthritis: a meta‐analysis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014; 32:11–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ et al 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2010; 62:2569–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA et al The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988; 31:315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kastbom A, Strandberg G, Lindroos A, Skogh T. Anti‐CCP antibody test predicts the disease course during 3 years in early rheumatoid arthritis (the Swedish TIRA project). Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63:1085–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ronnelid J, Wick MC, Lampa J et al Longitudinal analysis of citrullinated protein/peptide antibodies (anti‐CP) during 5 year follow up in early rheumatoid arthritis: anti‐CP status predicts worse disease activity and greater radiological progression. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64:1744–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van der Helm‐van Mil AH, Verpoort KN, Breedveld FC, Toes RE, Huizinga TW. Antibodies to citrullinated proteins and differences in clinical progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2005; 7:R9499–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Woude D, Syversen SW, van der Voort EI et al The ACPA isotype profile reflects long‐term radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010; 69:1110–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Venrooij WJ, van Beers JJ, Pruijn GJ. Anti‐CCP antibodies: the past, the present and the future. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2011; 7:391–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karlson EW, Lee IM, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE, Hennekens CH. A retrospective cohort study of cigarette smoking and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in female health professionals. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42:910–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Olsson AR, Skogh T, Axelson O, Wingren G. Occupations and exposures in the work environment as determinants for rheumatoid arthritis. Occup Environ Med 2004; 61:233–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Papadopoulos NG, Alamanos Y, Voulgari PV, Epagelis EK, Tsifetaki N, Drosos AA. Does cigarette smoking influence disease expression, activity and severity in early rheumatoid arthritis patients? Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005; 23:861–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stolt P, Bengtsson C, Nordmark B et al Quantification of the influence of cigarette smoking on rheumatoid arthritis: results from a population based case–control study, using incident cases. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62:835–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Uhlig T, Hagen KB, Kvien TK. Current tobacco smoking, formal education, and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1999; 26:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vessey MP, Villard‐Mackintosh L, Yeates D. Oral contraceptives, cigarette smoking and other factors in relation to arthritis. Contraception 1987; 35:457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gregersen PK, Silver J, Winchester RJ. The shared epitope hypothesis. An approach to understanding the molecular genetics of susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1987; 30:1205–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jawaheer D, Gregersen PK. Rheumatoid arthritis. The genetic components. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2002; 28:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kallberg H, Ding B, Padyukov L et al Smoking is a major preventable risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis: estimations of risks after various exposures to cigarette smoke. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70:508–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Klareskog L, Stolt P, Lundberg K et al A new model for an etiology of rheumatoid arthritis: smoking may trigger HLA‐DR (shared epitope)‐restricted immune reactions to autoantigens modified by citrullination. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54:38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Linn‐Rasker SP, van der Helm‐van Mil AH, van Gaalen FA et al Smoking is a risk factor for anti‐CCP antibodies only in rheumatoid arthritis patients who carry HLA‐DRB1 shared epitope alleles. Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65:366–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Padyukov L, Silva C, Stolt P, Alfredsson L, Klareskog L. A gene–environment interaction between smoking and shared epitope genes in HLA‐DR provides a high risk of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50:3085–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laki J, Lundström E, Snir O et al Very high levels of anti‐citrullinated protein antibodies are associated with HLA‐DRB1*15 non‐shared epitope allele in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64:2078–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reynisdottir G, Olsen H, Joshua V et al Signs of immune activation and local inflammation are present in the bronchial tissue of patients with untreated early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016; 75:1722–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Svard A, Skogh T, Alfredsson L et al Associations with smoking and shared epitope differ between IgA‐ and IgG‐class antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015; 67:2032–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Divergent immunoglobulin G subclass activity through selective Fc receptor binding. Science 2005; 310:1510–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Olas K, Butterweck H, Teschner W, Schwarz HP, Reipert B. Immunomodulatory properties of human serum immunoglobulin A: anti‐inflammatory and proinflammatory activities in human monocytes and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Clin Exp Immunol 2005; 140:478–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mestecky J, Russell MW, Elson CO. Perspectives on mucosal vaccines: is mucosal tolerance a barrier? J Immunol 2007; 179:5633–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Davies AM, Sutton BJ. Human IgG4: a structural perspective. Immunol Rev 2015; 268:139–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Svard A, Kastbom A, Reckner‐Olsson A, Skogh T. Presence and utility of IgA‐class antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides in early rheumatoid arthritis: the Swedish TIRA project. Arthritis Res Ther 2008; 10:R75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Verpoort KN, Jol‐van der Zijde CM, Papendrecht‐van der Voort EA et al Isotype distribution of anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies in undifferentiated arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis reflects an ongoing immune response. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54:3799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Svard A, Kastbom A, Soderlin MK, Reckner‐Olsson A, Skogh T. A comparison between IgG‐ and IgA‐class antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides and to modified citrullinated vimentin in early rheumatoid arthritis and very early arthritis. J Rheumatol 2011; 38:1265–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chapuy‐Regaud S, Nogueira L, Clavel C, Sebbag M, Vincent C, Serre G. IgG subclass distribution of the rheumatoid arthritis‐specific autoantibodies to citrullinated fibrin. Clin Exp Immunol 2005; 139:542–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Panza F, Pratesi F, Valoriani D, Migliorini P. Immunoglobulin G subclass profile of anticitrullinated peptide antibodies specific for Epstein Barr virus‐derived and histone‐derived citrullinated peptides. J Rheumatol 2014; 41:407–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kimata H, Yoshida A, Ishioka C, Jiang Y, Kusunoki T, Mikawa H. Monomeric IgG2 enhances Ig production and proliferation in human B cells. Biotechnol Ther 1993; 4:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen K, Cerutti A. New insights into the enigma of immunoglobulin D. Immunol Rev 2010; 237:160–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ichikawa D, Asano M, Shinton SA et al Natural anti‐intestinal goblet cell autoantibody production from marginal zone B cells. J Immunol 2015; 194:606–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Magri G, Miyajima M, Bascones S et al Innate lymphoid cells integrate stromal and immunological signals to enhance antibody production by splenic marginal zone B cells. Nat Immunol 2014; 15:354–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhu LY, Shao T, Nie L, Zhu LY, Xiang LX, Shao JZ. Evolutionary implication of B‐1 lineage cells from innate to adaptive immunity. Mol Immunol 2016; 69:123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hajishengallis G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2015; 15:30–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gonzalez D, Tzianabos AO, Genco CA, Gibson FC 3rd. Immunization with Porphyromonas gingivalis capsular polysaccharide prevents P. gingivalis‐elicited oral bone loss in a murine model. Infect Immun 2003; 71:2283–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vidarsson G, Dekkers G, Rispens T. IgG subclasses and allotypes: from structure to effector functions. Front Immunol 2014; 5:520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bagaitkar J, Daep CA, Patel CK, Renaud DE, Demuth DR, Scott DA. Tobacco smoke augments Porphyromonas gingivalis–Streptococcus gordonii biofilm formation. PLOS ONE 2011; 6:e27386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mikuls TR, Payne JB, Reinhardt RA et al Antibody responses to Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis. Int Immunopharmacol 2009; 9:38–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aalberse RC, van der Gaag R, van Leeuwen J. Serologic aspects of IgG4 antibodies. I. Prolonged immunization results in an IgG4‐restricted response. J Immunol 1983; 130:722–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rantapaa‐Dahlqvist S, de Jong BA, Berglin E et al Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2003; 48:2741–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang W, Li J. Identification of natural bispecific antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and immunoglobulin G in rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One 2011; 6:e16527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chen LF, Mo YQ, Ma JD, Luo L, Zheng DH, Dai L. Elevated serum IgG4 defines specific clinical phenotype of rheumatoid arthritis. Mediators Inflamm 2014; 2014:635293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mihai S, Chiriac MT, Herrero‐González JE et al IgG4 autoantibodies induce dermal‐epidermal separation. J Cell Mol Med 2007; 11:1117–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tokunaga NK, Noda R, Kaneoka H et al Association between HLA‐DRB1*15 and Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis complicated by renal involvement. Nephron 1999; 81:165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mattey DL, González‐Gay MA, Hajeer AH et al Association between HLA‐DRB1*15 and secondary Sjogren's syndrome in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2000; 27:2611–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Feitsma AL, van der Helm‐van Mil AH, Huizinga TW, de Vries RR, Toes RE. Protection against rheumatoid arthritis by HLA: nature and nurture. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67(Suppl.3):iii61–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]