Abstract

The synthetic cyclic hexapeptide cWFW (cyclo(RRRWFW)) has a rapid bactericidal activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Its detailed mode of action has, however, remained elusive. In contrast to most antimicrobial peptides, cWFW neither permeabilizes the membrane nor translocates to the cytoplasm. Using a combination of proteome analysis, fluorescence microscopy, and membrane analysis we show that cWFW instead triggers a rapid reduction of membrane fluidity both in live Bacillus subtilis cells and in model membranes. This immediate activity is accompanied by formation of distinct membrane domains which differ in local membrane fluidity, and which severely disrupts membrane protein organisation by segregating peripheral and integral proteins into domains of different rigidity. These major membrane disturbances cause specific inhibition of cell wall synthesis, and trigger autolysis. This novel antibacterial mode of action holds a low risk to induce bacterial resistance, and provides valuable information for the design of new synthetic antimicrobial peptides.

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have been in the focus of research attention as a promising alternative for conventional antibiotics1. The subclass of arginine- and tryptophan-rich peptides, with cationic charge and hydrophobic residues, provides the ideal structural prerequisite for interaction with the negatively charged bacterial membranes2. To elucidate optimal structure-activity properties we screened a library of small synthetic peptides derived from the active motif of human antimicrobial peptide lactoferricin3. This analysis identified the cyclic hexapeptide cWFW (cyclo-RRRWFW) as the most potent candidate. It turned out that this peptide is active against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria at low micromolar concentrations, and displays strong selectivity, i.e. it is not toxic towards human cells4. The antibacterial activity of cWFW is further characterised by a rapid killing kinetic and a bactericidal effect at the minimal inhibitory concentration5. To develop cWFW as a novel, highly efficient antibiotic lead compound, we now need a precise knowledge of its mechanism of action.

Earlier studies have suggested that the cytoplasmic membrane is the primary peptide target but it is unknown how this interaction kills bacteria5,6. In contrast to most AMPs, however, cWFW does not permeabilize the cell membrane to large molecules5,6. As first postulated by Epand and Epand7, short cationic AMPs might, as an alternative mechanism, induce clustering of anionic lipids within the bacterial membrane due to electrostatic interactions8. This effect, which is highly dependent on the phospholipid composition and requires the presence of both negatively charged and zwitterionic lipid species, could later be confirmed for small cyclic hexapeptides including cWFW in vitro9,10. Whether this clustering indeed takes place in vivo, and whether it contributes to the antibacterial activity of cWFW has so far remained unanswered.

In this manuscript, we now present a comprehensive mode of action analysis demonstrating that cWFW, uniquely for a cationic antimicrobial peptide, neither depolarises the membrane nor otherwise adversely affects the energy state of the cell. Instead, cWFW strongly reduces membrane fluidity both in vivo and in vitro, and triggers a large scale phase-separation of the cytoplasmic membrane. In contrast to the previously suggested models, the cWFW-triggered lipid phase separation is independent of both the negatively charged phospholipid cardiolipin and the zwitterionic phospholipid phosphatidyl ethanolamine, and thus represents a novel activity for a membrane-targeting peptide. Moreover, the in vivo domain formation causes a striking segregation of peripheral and integral membrane proteins into separate membrane areas. This strong disturbance of membrane organisation inhibits cell wall synthesis and triggers autolysis. We consider these effects as a novel mechanism of action for antimicrobial peptides, and discuss the implication on antimicrobial resistance.

Results

Analysis of the cWFW-triggered cellular stress response

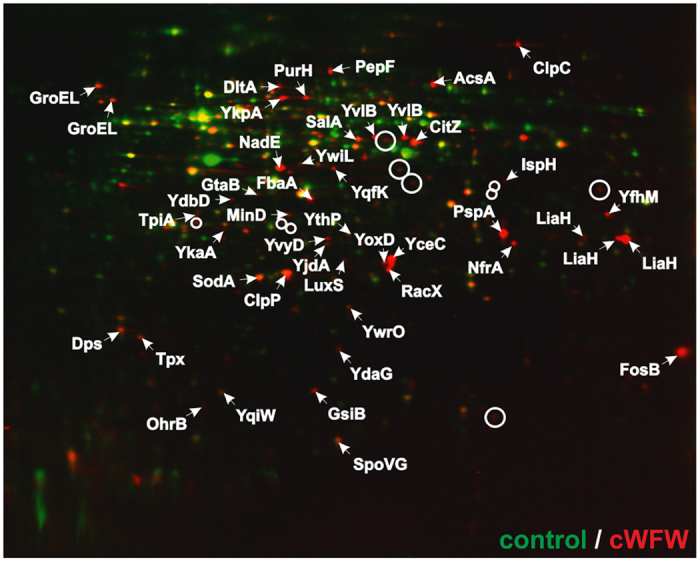

To identify which cellular processes are disturbed by cWFW, we performed proteomic profiling of the Gram-positive model organism B. subtilis (Fig. 1). This technique combines radioactive pulse-labeling of newly synthesised proteins with two-dimensional SDS PAGE, thus providing insight into the acute antibiotic stress response11. The proteomic stress response profile, consisting of marker proteins upregulated after antibiotic addition, is highly specific for the imposed stress and thus indicative of the antibiotic’s mechanism of action11.

Figure 1. Cytosolic proteome response profile of B. subtilis to cWFW.

Autoradiographs of antibiotic-treated cells (red) were overlaid with those of untreated controls (green). Upregulated proteins in response to cWFW treatment (8 μM) appear red, down-regulated proteins green. Proteins synthesised at equal rates appear yellow. Proteins upregulated more than 2-fold in three biological replicates were defined as marker proteins and identified by mass spectrometry. Unidentified marker proteins are indicated by circles. See supplementary Figure 1a for the growth inhibition of B. subtilis observed in BMM with different cWFW concentrations. Strain used: B. subtilis 168/DSM 402.

In agreement with the cytoplasmic membrane as the likely cellular target6, cWFW elicited a typical cell envelope stress response characterised by upregulation of proteins controlled by the extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors SigM, SigW and SigX (Table 1). In addition, marker proteins indicative of membrane damage (phage shock protein PspA and NAD synthase NadE) and impairment of membrane-bound steps of cell wall synthesis (PspA homologue LiaH and the Sigma M-controlled protein YpuA) were upregulated. Further upregulated proteins point towards remodeling of the cell wall (RacX, DltA) and membrane (YjdA, YoxD, IspH), accompanied by changes in central carbon metabolism (TpiA, FbaA, CitZ) and activation of the SigB-dependent general stress response.

Table 1. Marker proteins upregulated upon cWFW treatment.

| protein | induction factor | known or predicted function | regulon | functional category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YceC* | 9.9 | similar to tellurium resistance protein | SigW, SigM, SigB, SigX | cell envelope general stress |

| FosB | 8.3 | bacillithiol-S-transferase, fosfomycin resistance | SigW | cell envelope |

| YfhM | 5.8 | similar to epoxide hydrolase, general stress protein | SigW, SigB | cell envelope general stress |

| YthP | 5.9 | similar to ABC transporter (ATP-binding protein) | SigW | cell envelope |

| YvlB | 9.0 | unknown | SigW | cell envelope |

| GtaB | 3.2 | UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase, general stress protein | SigB | cell envelope general stress |

| LiaH# | 16.6 | similar to phage shock protein | LiaRS | cell wall |

| RacX | 12.0 | amino acid racemase | SigW | cell wall |

| YpuA# | 4.0 | unknown | SigM | cell wall |

| DltA | 4.2 | D-alanyl-D-alanine carrier protein ligase, antimicrobial peptide resistance | SigD, SigM, SigX, Spo0A | cell wall |

| PspA° | 9.5 | phage shock protein A homologue | SigW, AbrV | membrane |

| AcsA | 3.7 | acetyl-CoA synthetase | CcpA, CodY | membrane |

| YjdA | 3.4 | similar to 3-oxoacyl-acyl-carrier protein reductase | unknown | membrane |

| YoxD | 7.1 | similar to 3-oxoacyl-acyl-carrier protein reductase | unknown | membrane |

| IspH | 19.0 | 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase, isoprene biosynthesis | unknown | membrane |

| NadE° | 11.0 | NAD synthase | SigB | energy |

| NfrA | 5.7 | FMN-containing NADPH-linked nitro/flavin reductase | SigD, Spo0A, Spx | energy |

| YwrO | 4.3 | similar to NAD(P)H oxidoreductase | unknown | energy |

| CitZ | 3.5 | citrate synthase | CcpA, CcpC | energy |

| YqkF | 7.7 | similar to oxidoreductase | unknown | energy |

| TpiA | 5.8 | triose phosphate isomerase, glycolytic/gluconeogenic enzyme | CggR | energy |

| YwjI | 6.4 | class II fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, gluconeogenesis | unknown | energy |

| FbaA | 2.9 | fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase, glycolytic/gluconeogenic enzyme | unknown | energy |

| PepF | 3.6 | oligoendopeptidase | unknown | phosphorelay |

| PurH | 3.4 | phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxamide formyltransferase | PurR, G-box | nucleotide biosynthesis |

| GsiB | 8.4 | general stress protein | SigB | general stress |

| YvyD | 6.2 | general stress protein, required for ribosome dimerization in stationary phase | SigB, SigH | general stress |

| YdaG | 5.6 | general stress protein | SigB | general stress |

| OhrB | 4.4 | general stress protein | SigB | general stress |

| Dps | 5.2 | general stress protein, iron storage protein | SigB | general stress iron metabolism |

| ClpP | 4.8 | ATP-dependent Clp protease proteolytic subunit (class III heat-shock protein) | SigB, CtsR | general stress heat shock |

| ClpC | 5.4 | ATPase subunit of the ATP-dependent ClpC-ClpP protease | SigB, SigF, CtsR | general stress heat shock |

| GroEL | 3.9 | chaperonin | HrcA | chaperone heat shock |

| SodA | 3.0 | superoxide dismutase | SigB | oxidative stress |

| Tpx | 4.1 | thiol peroxidase | Spx | oxidative stress |

| YqiW | 2.4 | unknown, disulfide isomerase family | unknown | oxidative stress |

| YdbD | 19.4 | similar to manganese-containing catalase | SigB | oxidative stress |

| LuxS | 3.4 | S-ribosylhomocysteine lyase, swarming, biofilm formation, methionine salvage | unknown | motility, biofilm |

| MinD | 3.1 | cell division site placement | SigH, SigM | cell division envelope stress |

| SpoVG | 2.4 | negative effector of asymmetric septation | SigH. SinR, AbrB | cell division sporulation |

| YkaA | 4.6 | unknown | Spo0A | sporulation |

| SalA | 3.5 | negative regulator of scoC expression, derepression of subtilisin | ScoC, SalA | gene regulation proteolysis |

*Specific marker for cell envelope stress, °specific marker for membrane stress, #specific marker for inhibition of membrane-bound cell wall biosynthesis steps43.

When comparing the cWFW-triggered stress response to a proteome response library12 we found the highest overlap with the antimicrobial peptide MP196, but also a striking similarity with gramicidin S and valinomycin (Supplementary Table 1). The linear hexapeptide MP196 de-energises the cell by inhibition of respiration13 whereas the cyclodecapeptide gramicidin S dissipates membrane potential via transient ion conductance events14. Membrane depolarisation caused by the ion carrier valinomycin is a direct result of specific potassium transport15. Similarities in the proteomic response elicited by compounds which directly interfere with cell wall synthesis such as vancomycin and mersacidin, or other specific ionophores such as gramicidin A or ionomycin were comparably low (Supplementary Table 1).

Together, these results argue against a specific proteinaceous target for cWFW. Instead, cWFW is more likely to target the cytoplasmic membrane and to cause extensive interference with membrane-associated processes including energy metabolism, cell wall synthesis, and membrane homeostasis. The following paragraphs focus on how cWFW affects these different aspects of B. subtilis physiology.

Membrane permeability and cell energy state

Earlier investigations have suggested that cWFW does not permeabilize the cytoplasmic membrane of E. coli, or form pores in model membranes5,6. However, the induction of the general SigB-dependent stress response and the similarity of the proteomic response triggered by MP196 and gramicidin S suggests that cWFW might nevertheless cause energy starvation linked to membrane depolarisation in B. subtilis.

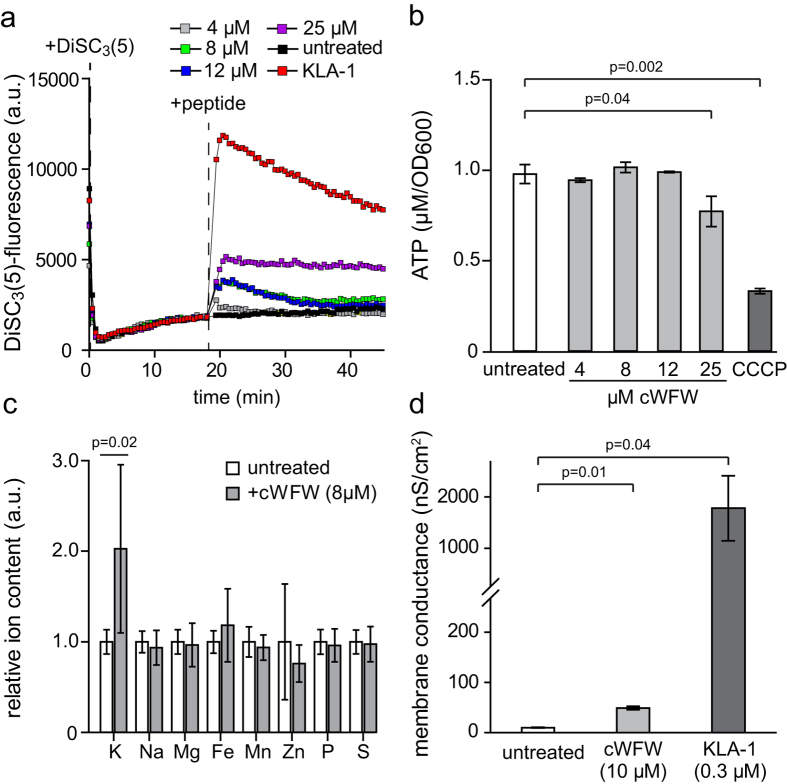

To test this possibility, we first analysed the cellular membrane potential with the voltage-sensitive dye DiSC3(5)16. As shown in Fig. 2a, the fluorescence intensity of DiSC3(5)-stained cell suspension was slightly increased at growth-inhibitory concentrations (8 μM) and above (Supplementary Figure 1). This indicates a detectable degree of membrane depolarisation caused by cWFW but the observed effect was very low compared to that of the positive control KLA-1, which is a pore-forming peptide fully dissipating the membrane potential17. In addition, cWFW-induced depolarisation was only transient at growth-inhibitory concentrations (8–12 μM) and the membrane potential was restored almost to control levels within 10 min (Fig. 2a). In agreement with these measurements, a minor reduction of cellular ATP levels was observed only at elevated concentrations of cWFW (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. Impact of cWFW on cell energy state and membrane permeability.

(a) Membrane potential levels of B. subtilis upon addition of different cWFW concentrations were measured using fluorescent voltage-sensitive dye DiSC3(5). For positive control, cells were depolarised by addition of the helical pore-forming antimicrobial peptide KLA-1 (40 μM). The time points of DiSC3(5) and peptide additions are highlighted with dashed lines. See supplementary Figure 1b for growth inhibition at identical cWFW-concentrations and cell densities. The graph depicts a representative measurement of three independent replicates. (b) ATP levels in B. subtilis after 20 min incubation with different cWFW concentrations were measured using a Luciferase-based luminescence assay. For positive control, cells were incubated with the proton ionophore CCCP (100 μM). Cell densities are comparable to the data shown in panel A and supplementary Figure 1b. The diagram depicts the average and standard deviation values of three independent replicates. No significant changes (p ≥ 0.05) were observed for samples treated with 4, 8, and 12 μM cWFW. (c) Changes in relative ion content of B. subtilis upon 15 min incubation with 8 μM cWFW were determined using inductively-coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). Phosphorus, mainly prevalent in DNA-bound form, served as internal control for cell mass. The diagram depicts the average and standard deviation values of three independent measurements. No significant changes (p ≥ 0.05) were observed ions other than K+. See supplementary Figure S1a for the growth inhibition of B. subtilis observed in BMM with different cWFW concentrations. (d) Conductivity measurements on planar lipid membranes formed of E. coli lipid extract upon addition of 10 μM cWFW. The pore-forming helical peptide KLA-1 (0.3 μM) served as positive control. The diagram depicts the average and standard error of two independent measurements. The statistical significances were calculated using unpaired (panels b/d) and paired (panel c) two-tailed Student t test. Strains used: (a/b) B. subtilis 168, (c) B. subtilis 168/DSM 402.

To verify these findings with independent assays, we next analysed cWFW-triggered changes in cellular ion content, and performed conductivity measurements on bacterial model membranes. Consistent with the lack of significant membrane depolarisation, no leakage of cellular ions was observed in vivo (Fig. 2c). In contrast, an accumulation of K+ upon addition of cWFW was observed. At last, only a minor ion flux was induced in model bilayers compared to the pore-forming peptide KLA-1 (Fig. 2d).

Together, these analyses demonstrate that cWFW neither permeabilizes the cytoplasmic membrane nor acts as a carrier for the analysed ion species. cWFW thus exhibits a mode of action which clearly sets it apart from typical membrane targeting antimicrobial peptides which either form ion-conducting pores, or otherwise interfere with the membrane diffusion barrier function and cell energy state.

cWFW interferes with membrane homeostasis by reducing membrane fluidity

Although the membrane barrier function is not significantly impaired, there is convincing evidence that cWFW can directly influence lipid bilayers upon binding10,18. Therefore, we focussed on analysing two plausible effects through which cWFW could interfere with the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane: (i) disturbance of membrane homeostasis and (ii) lipid domain formation.

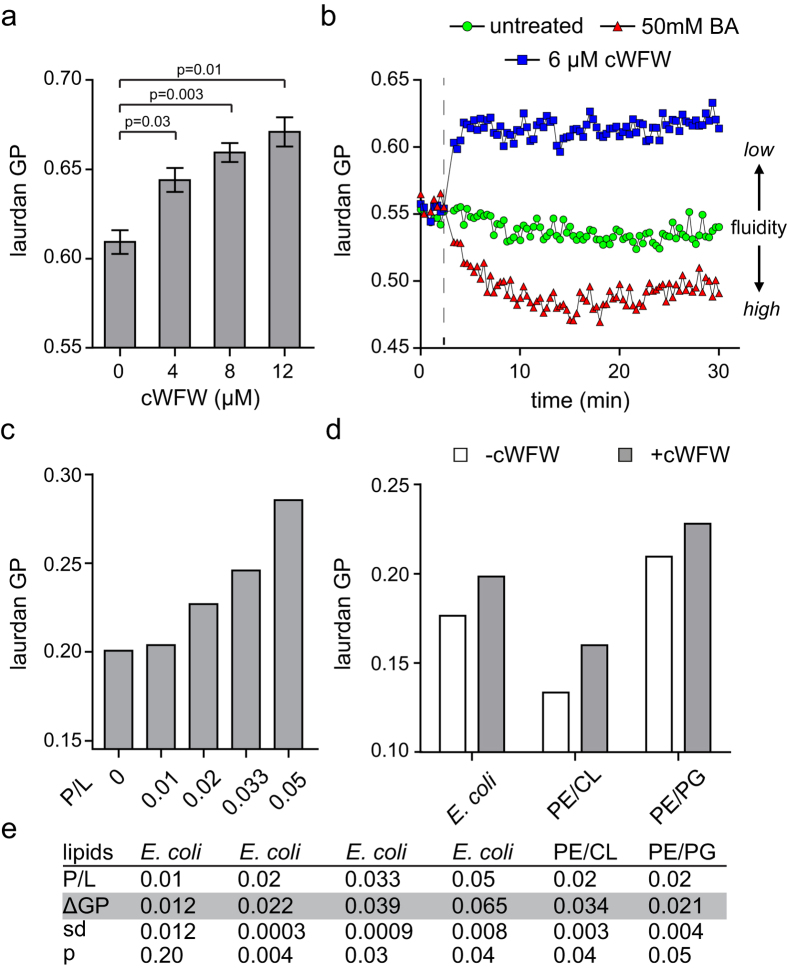

Biological membranes are maintained in an appropriate state of fluidity which optimally promotes the activity and diffusion of membrane proteins while maintaining sufficiently low passive permeability19. Antimicrobial peptide-triggered changes in fluidity have been observed in model membranes systems in vitro20,21, and very recently for the lipopeptide daptomycin in vivo22. To test whether cWFW can disturb the fluidity of the cytoplasmic membrane, we used the fluidity-sensitive fluorescent dye laurdan. Indeed, a clear concentration-dependent increase in laurdan generalised polarisation (GP) was observed upon incubation of B. subtilis with cWFW (Fig. 3a). This indicates a substantial reduction of membrane fluidity. Crucially, minor changes were already observed at concentrations which are growth-limiting but not sufficient to fully abolish growth (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 3. cWFW reduces membrane fluidity in vivo and in vitro.

(a) The fluidity of the cytoplasmic membrane was measured for B. subtilis cells upon 10 min incubation with increasing concentrations of cWFW using the fluidity-sensitive fluorescent dye laurdan. Please note that high laurdan generalised polarisation (GP) correlates with low membrane fluidity. The diagram depicts the average and standard deviation of three replicate measurements. (b) Time-resolved laurdan generalised polarisation (GP) was measured upon addition of 6 μM cWFW. As a positive control, 50 mM of the membrane fluidiser benzyl alcohol (BA) was added to a replicate sample. The time point of addition is indicated with a dashed line. The graph depicts a representative measurement of three independent replicates. (c) Laurdan GP was measured for large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) formed of E. coli polar lipid extract in the presence of increasing concentrations of cWFW. The peptide-to-lipid molar ratios (P/L) are indicated below the graph. See supplementary Figure S3b for examples of the recorded spectra. (d) Laurdan GP in the presence and absence of cWFW (P/L = 0.02) was measured for LUVs with varying lipid compositions (lipid molar ratios: PE/CL 87.5/12.5, PE/PG 75/25). See supplementary Figure 3c–f for recorded spectra. PE: palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine, PG: palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidylglycerol, CL: cardiolipin and E. coli: E. coli polar lipid extract. (e) Average and standard deviation of cWFW-induced changes in laurdan GP (ΔGP) are shown for the different lipid compositions and peptide-to-lipid molar ratios (P/L) from two independent experiments. The statistical significances were calculated using unpaired (panels a) and paired (panel e) two-tailed Student t test.

B. subtilis can adjust the membrane fatty acid composition and thus membrane fluidity upon stress23. Unsurprisingly, the cWFW-dependent membrane disturbances also trigger an adaptive response on the level of membrane fatty acid composition. (Supplementary Figure 2). To distinguish between a direct activity of cWFW and a potential cellular adaptation process, we measured time-resolved laurdan GP upon addition of cWFW (Fig. 3b). It turned out that the reduction of membrane fluidity occurs very rapidly upon addition and reaches a steady state within only 2 min, thus suggesting that observed membrane rigidification is a direct consequence of cWFW-membrane interaction.

To verify that the reduction of membrane fluidity is indeed direct activity of cWFW and to gain insight into a possible lipid-specificity of this phenomenon, we analysed the ability of cWFW to reduce membrane fluidity in an in vitro model system using large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) composed of bacterial membrane lipids. A distinct concentration-dependent reduction of membrane fluidity was observed with liposomes formed from E. coli polar lipid extracts (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Figure 3b). This confirms that membrane rigidification is indeed a direct consequence of cWFW intercalation into the lipid bilayer. We next analysed whether the ability of cWFW to reduce membrane fluidity requires a complex fatty acid composition found in biological membranes, or relies on the presence of specific phospholipid head group species. For this aim, we repeated the experiments with liposomes composed of binary mixtures of POPE/POPG and POPE/CL, respectively. A clear reduction of membrane fluidity was observed in both cases, indicating that the peptide activity is independent of the investigated composition of POPE-based lipid mixtures which mimic bacterial membranes (Fig. 3d and e). However, we did observe a slightly stronger reduction of fluidity in liposomes containing cardiolipin, a result consistent with the preferred partitioning of cWFW into cardiolipin-containing POPE membranes6.

In summary, the intercalation of cWFW into lipid bilayers results in a rapid reduction of membrane fluidity both on the cellular level and in model lipid bilayers. For the investigated bilayer systems, the ability to reduce membrane fluidity is independent of specific fatty acids or lipid head groups.

cWFW triggers a novel type of lipid domain formation in vivo

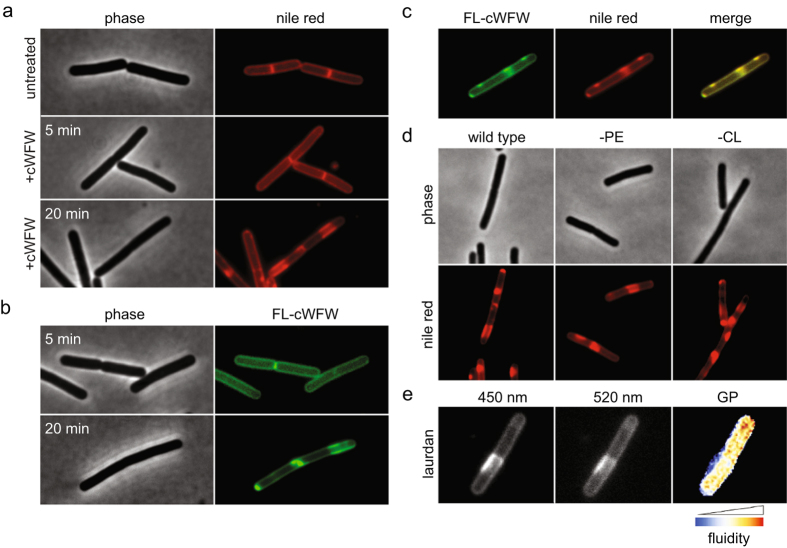

The reduction of membrane fluidity upon addition of cWFW can either be caused by a uniform effect on the cytoplasmic membrane or by formation of specific domains which differ in fluidity. To address this question, we analysed cells stained with the fluidity-sensitive uncharged membrane dye nile red24,25. Upon addition of cWFW, the fluorescent membrane stain initially remained homogeneous indicating that the reduction of membrane fluidity extends to the entire cytoplasmic membrane (Fig. 4a). However, after a prolonged incubation, a striking separation of the membrane into two distinct areas was observed (Fig. 4a). This lipid domain formation was also reflected in the distribution of fluorescently labelled cWFW (Fig. 4b and c).

Figure 4. cWFW triggers large-scale lipid domain formation in vivo.

(a) Phase contrast and fluorescence images of B. subtilis cells stained with fluorescent membrane dye nile red before addition (upper panels) and after 5 min (middle panels) and 20 min (lower panels) incubation with cWFW (12 μM). (b) Phase contrast and fluorescence images of B. subtilis cells stained with a 1:5 mix of NBD-labelled (FL-cWFW) and unlabelled cWFW (combined concentration of 12 μM) after 5 min (upper panels) and 20 min (lower panels) incubation. (c) Fluorescence images of B. subtilis cells stained with NBD-labelled peptide (FL-cWFW; left panel) and nile red (middle panel) upon 20 min incubation. The right panel depicts a colour overlay of the images shown in left and middle panels. (d) Phase contrast and fluorescence images of B. subtilis cells stained with fluorescent membrane dye nile red after 20 min incubation with cWFW (12 μM). Depicted are wild type cells (left panels), cells deficient for phosphatidylethanolamine (-PE, middle panels), and cells deficient for cardiolipin (-CL, right panels). (e) Fluorescence images of B. subtilis cell stained with laurdan upon 20 min incubation with cWFW (12 μM). Depicted is the laurdan emission at 450 nm (left panel), 520 nm (middle panel) and a colour-coded laurdan GP map calculated from the images shown in left and middle panels, respectively. Strains used: (a–e) B. subtilis 168 (wild type), (d) B. subtilis HB5343 (Δpsd, PE-deficient) and B. subtilis SDB206 (ΔclsA, ΔclsB, ΔywiE, CL-deficient).

We have previously shown that cWFW treatment results in lipid demixing of PE/PG bilayers in vitro9,10. Moreover, PE and cardiolipin have been reported to form lipid domains in B. subtilis membranes26. The observed domains could therefore indicate aberrant clustering of these specific lipid species. To test this hypothesis, we repeated nile red staining with cells incapable of producing the zwitterionic PE or the negatively charged cardiolipin, respectively. To our surprise, the absence of neither of these major phospholipid species had an influence on the domain formation (Fig. 4d) or on the MIC of cWFW (Supplementary Table 4). Hence, the observed in vivo phase separation is not determined by clustering of PE or CL, or by the demixing of PE and negatively charged phospholipids. Instead, a microscopic analysis of laurdan GP revealed a clear difference in the local fluidity of the observed domains (Fig. 5e). The cWFW-triggered lipid domain formation thus exhibits characteristics reminiscent of membrane phase separation driven by changes in the physical state of the membrane, rather than by enrichment of specific lipid species.

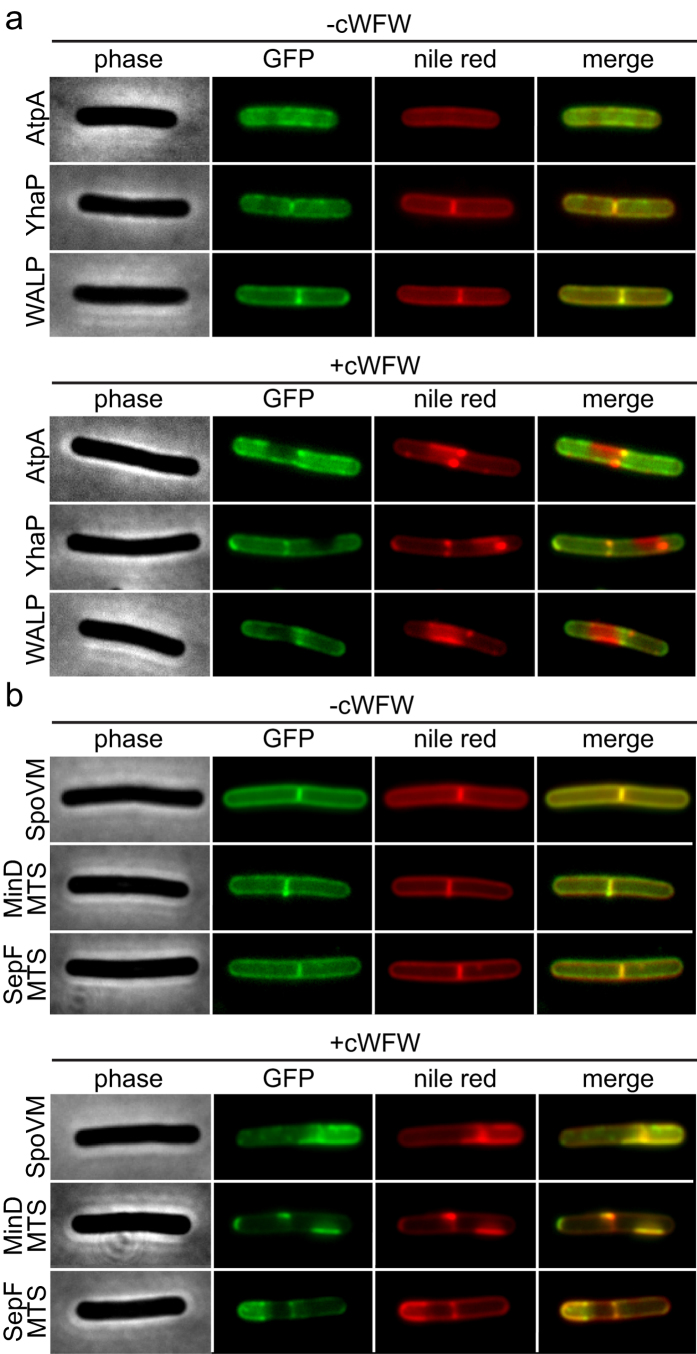

Figure 5. cWFW-triggered lipid domain formation segregates membrane proteins.

(a) Phase contrast, GFP-fluorescence, nile red-fluorescence and fluorescent colour overlays are depicted for cells expressing different integral membrane proteins in the absence (upper panels) and presence (lower panels) of cWFW (20 min incubation with 12 μM). (b) Comparable images are depicted for cells expressing different peripheral membrane proteins. Strains used: (a) B. subtilis BS23 (AtpA-GFP), B. subtilis HS41 (YhaP-GFP), B. subtilis HS64 (WALP23-GFP), (b) B. subtilis KR318 (SpoVM-GFP), B. subtilis HS65 (GFP-MinDMTS) and B. subtilis HS208 (SepFMTS-GFP).

Impact of cWFW-induced lipid domain formation on protein localisation

The massive cWFW-triggered phase separation of the cytoplasmic membrane is prone to influence the distribution of membrane proteins. To analyse the general impact of cWFW on membrane protein localisation, we followed three dispersedly localised integral membrane proteins24. The chosen native proteins were YhaP, a Na+ efflux pump, and AtpA, a subunit of the F1Fo ATP synthase. The selection was supplemented with WALP23, an artificial model transmembrane helix27. For comparison, we investigated three dispersedly localised peripheral membrane proteins which bind the membrane via an amphipathic helix. These proteins were the native sporulation protein SpoVM28 and two semi-synthetic proteins composed of GFP fused with the amphipathic helices of the cell division protein SepF and the cell division placement protein MinD, respectively29. As shown in Fig. 5, all six tested membrane proteins were clearly delocalised upon cWFW treatment, thus demonstrating that the lipid domain formation indeed strongly affects membrane protein localisation (Fig. 5a). Surprisingly, whereas the integral membrane proteins were excluded from peptide-enriched domains, the analysed peripheral membrane proteins were accumulated in exactly these regions (Fig. 5b).

Taken together, the cWFW-triggered membrane phase-separation not only severely disrupts the overall membrane protein organisation, but also segregates membrane proteins into separate areas based on the type of membrane anchor utilised. This effect will inevitably cause major disturbances in membrane-associated cellular processes, and provides an explanation for the multitude of inhibitory effects observed in the proteome analysis.

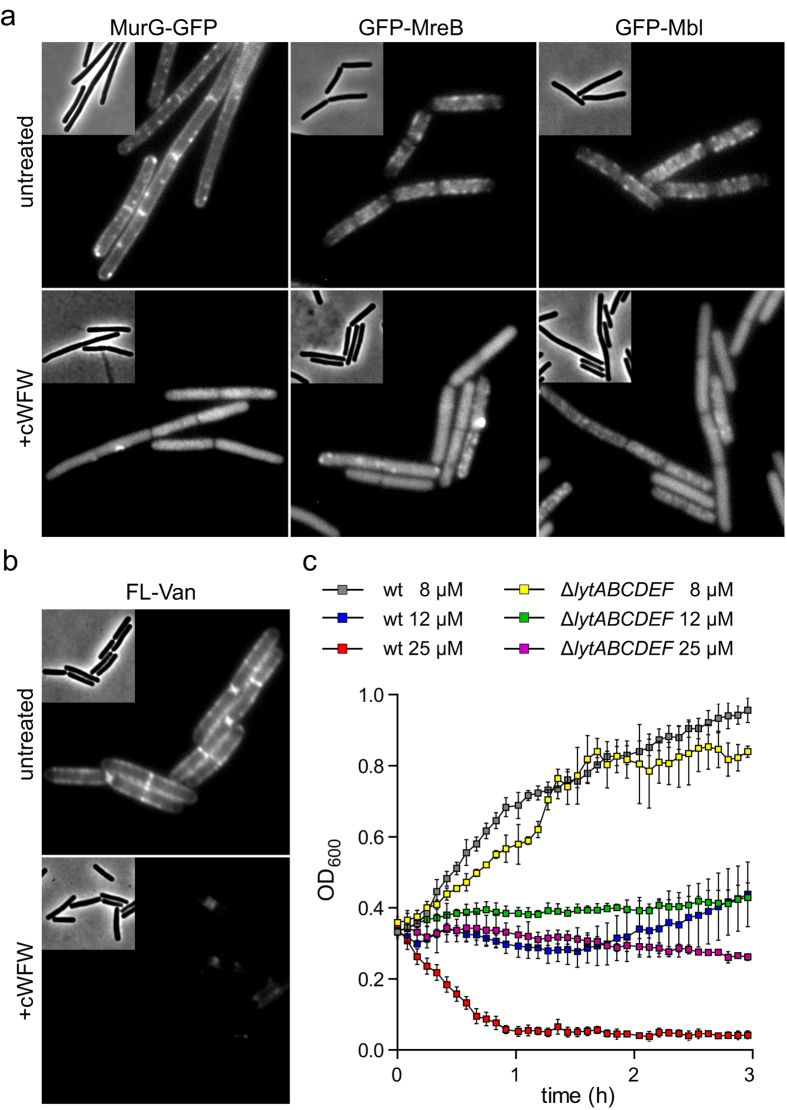

Impact of protein delocalisation on inhibition of cell wall synthesis

Having identified the reduction of membrane fluidity and membrane phase separation as the mechanistic basis of the antimicrobial activity of cWFW, we further investigated how this leads to the observed rapid growth-inhibition of fully energised cells. B. subtilis grows by integrating two main processes: localised cell wall synthesis expanding the cell envelope and cell division separating the daughter cells. The proteome profile indicated that cWFW triggers a stress-response associated with inhibition of cell wall precursor lipid II biosynthesis, an essential process for both cell elongation and division. The observed inhibition of cell growth could therefore be caused by interference with cell wall synthesis. Two central membrane associated players in this process are the glycosyltransferase MurG, which catalyses the last step of lipid II synthesis30, and bacterial actin homologs of the MreB-type, which govern the correct cellular positioning of the lateral cell wall synthetic machinery31. In agreement with the stress response indicating disturbance in lipid II synthesis, cWFW triggered a release of both MurG and MreB-homologs from the membrane (Fig. 6a). To support this finding, we analysed whether the bacteria are able to synthesise lipid II in the presence of cWFW by staining the cells with a fluorescent derivative of the lipid II-binding antibiotic vancomycin (FL-Van). In B. subtilis, a high carboxypeptidase activity of PBP5 removes the vancomycin target D-Ala-D-Ala from matured cell wall. As a consequence, FL-Van binding is directly associated with lipid II and newly synthetised cell wall32. Indeed, a strong decrease of FL-Van staining was observed in cWFW-treated cells indicating significantly reduced amounts of lipid II (Fig. 6b). Together these findings provide strong evidence that cell wall synthesis is efficiently inhibited by cWFW.

Figure 6. cWFW inhibits cell wall synthesis and triggers autolysis.

(a) Phase contrast and fluorescence images of B. subtilis cells expressing MurG-GFP, GFP MreB and GFP-Mbl are depicted in the absence (upper panels) and presence (lower panels) of cWFW (20 min incubation with 12 μM). (b) Phase contrast and fluorescence images of B. subtilis wild type cells stained with fluorescent vancomycin (FL-Van) in the absence (upper panel) and presence (lower panel) of cWFW (20 min incubation with 12 μM). (c) Changes in optical density of B. subtilis wild type cells (wt), and cells deficient for the autolytic enzymes LytCDEF upon incubation with different concentrations of cWFW. The diagram depicts the average and standard deviation of three replicate cultures. Please note that the lytABC operon encodes the amidase LytC and accessory proteins LytAB which are involved in regulation and secretion of LytC, respectively. Strains used: (a) B. subtilis 168, B. subtilis KS69 (GFP-MreB), B. subtilis KS70 (GFP-Mbl), and B. subtilis TNVS175 (MurG-GFP), (b) B. subtilis 168, and (c) B. subtilis 168 (wt) and B. subtilis KS19 (ΔlytABCDEF).

Lipid domain formation triggers cell wall autolysis

Addition of elevated concentrations of cWFW not only inhibits growth but also induces cell lysis (Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Movie 1). This seemingly contradicts our results showing that the membrane integrity is not significantly compromised. There is, however, another possibility to explain the observed lysis. In growing cells the cell wall sacculus needs to expand by incorporation of new cell wall material. This process requires a finely tuned balance between cell wall synthesis and degradation of the existing cell wall by autolytic enzymes while continuously maintaining the crucial function as a support for turgor pressure33. Upon disturbance of the cell wall synthesis, the cytoplasmic membrane can become insufficiently supported against the large pressure difference between the interior and the exterior of the cell. The resulting cell lysis is classically observed with antibiotics which, unlike cWFW, directly target the cell wall synthetic machinery34. However, the MreB-cytoskeleton is also involved in the regulation of autolytic enzyme activities35. The release of MreB and Mbl from the membrane could thus disturb the essential tight control of these potentially destructive cell wall degrading enzymes. To test this hypothesis, we analysed the bacteriolytic activity of cWFW in the absence of major autolysins LytCDEF. Indeed, the lysis triggered by cWFW was fully abolished in this strain background although the cells were still efficiently growth-inhibited (Fig. 6c). These results confirm that the lytic activity of cWFW is not due to disintegration of the cell membrane. Rather, cWFW causes weakening of the cell wall sacculus mediated by the cells’ own autolytic enzymes. The bacteriolytic property of cWFW is thus a consequence of triggered autolysis.

Discussion

In this study, we have analysed the mode of action of the small cyclic antimicrobial membrane-targeting peptide cWFW. We provide evidence that cWFW exhibits a complex mode of action which encompasses both the cytoplasmic membrane and the cell wall of B. subtilis. Upon integration into the membrane cWFW triggers a rapid reduction of membrane fluidity followed by lipid phase separation process. This domain formation not only disturbs the lipid matrix, but also causes a striking segregation of integral and peripheral membrane proteins into different membrane areas. Changes in the physical state and the composition of the immediate surrounding lipid bilayer can have a profound effect on membrane protein structure and function36,37,38. As a consequence, the cWFW-induced domain formation can both physically separate proteins which require close proximity for interaction or which catalyse successive steps in a biosynthetic pathway, and impair protein functionality due to conformational changes. The combined disturbances in membrane fluidity and protein localisation explain the broad cellular response to cWFW observed in the proteome analysis. In addition to causing general disarray of membrane-associated processes, cWFW inhibits cell wall synthesis by dissociating the actin homologs MreB and Mbl, and the lipid II synthesis protein MurG from the cytoplasmic membrane. In agreement with cell wall disturbance, the cell lysis triggered by cWFW is a consequence of misregulation of cell wall autolytic enzymes rather than membrane disruption. Therefore, the antibacterial mode of action of this small cyclic cationic peptide is a combination of strong interference with general membrane organisation accompanied by an inhibition of cell wall synthesis and triggered autolysis.

Cationic antimicrobial peptides are generally assumed to kill bacteria by interfering with the integrity of the cytoplasmic membrane thereby causing leakage of the cytoplasmic content and cell de-energisation39. Based on investigations on model membrane systems, diverse modes of peptide-triggered membrane permeabilization have been suggested ranging from the formation of discrete pores and detergent-like activity to more subtle mechanisms such as perturbation of lipid packing39,40,41. The ability to trigger membrane rigidification combined with lipid domain formation, rather than membrane permeabilization or depolarisation, clearly distinguishes cWFW from other cationic AMPs. Hence, the case of cWFW demonstrates that cell permeabilization and de-energisation are not the only mechanisms by which membrane targeting AMPs can elicit strong bactericidal activities. The observed cross-interference with the cell wall synthetic machinery is, however, not unique for cWFW. In fact, most membrane-targeting AMPs induce cellular stress responses linked to inhibition of cell wall synthesis42,43. Based on work carried out with human β-defensin 3, Sahl and co-workers postulated a central role for lipid II and its biosynthesis pathway in the inhibition of cell wall synthesis by antimicrobial peptides42,44. Later, the linear cationic peptide MP169 was shown to trigger membrane dissociation of lipid II synthesis protein MurG as part of its complex mode of action13. Very recently, daptomycin was shown to target the cell wall synthesis by a more specific mechanism which includes intercalation into lipid microdomains associated with the cell wall synthetic machinery22. The ability of the fluidity-reducing cWFW to efficiently inhibit cell wall synthesis adds to the mounting evidence that membrane-associated steps of cell wall precursor biosynthesis are extraordinarily sensitive to membrane disturbances. The dual impairment of both the cytoplasmic membrane and cell wall synthesis therefore represents a cellular weak point which is frequently exploited by membrane targeting AMPs. It is tempting to speculate that this phenomenon contributes to the low incidence of resistant mutations emerging against cWFW (unpublished data), and in general against membrane targeting AMPs45.

In the context of lipid domains caused by AMPs, the discussion has focussed on the separation of anionic and zwitterionic lipids caused by preferential binding of cationic peptides to the negatively charged lipids40,46. The resulting phase boundary effects are considered the basis for the enhanced permeability of the lipid matrix47,48. In this manuscript, we provide direct microscopic in vivo evidence for peptide-induced formation of large lateral lipid domains in B. subtilis. Instead of demixing of anionic and zwitterionic lipids, however, the observed lipid domains display a difference in membrane fluidity. The cWFW-triggered domain formation is thus conceptually comparable to a phase-behaviour of lipid bilayers, and bears an intriguing similarity to cholesterol-induced membrane rigidification and lipid-raft formation49. The co-occurring segregation of membrane proteins adds a significant level of complexity to the phenomenon. Rather than being driven by a bona fide phase separation between fluid and less fluid lipid regions, the observed domain formation could also be caused by cWFW-induced changes in bilayer thickness, an effect frequently observed for antimicrobial peptides50. The segregation of integral membrane proteins away from the cWFW-enriched domains could be triggered by a hydrophobic mismatch between the transmembrane domains and the peptide-enriched membrane areas. The membrane areas with low density of integral membrane proteins could, in turn, attract peripheral membrane proteins and lipid dyes due to the increased surface area available for binding. Substantial amount of future work, both in vivo and in vitro, is required to understand the detailed molecular characteristics of the cWFW-triggered lipid domains. Nevertheless, our findings confirm that lipid phase separation and related protein segregation into the separate membrane domains are the key events in the mode of action of the cyclic R-, W-rich hexapeptide cWFW.

In summary, the antimicrobial mechanism of this membrane-active, non-depolarising peptide is based on substantial disruption of the lipid and protein organisation of the cytoplasmic membrane which has severe consequences for essential cellular processes as exemplified by the inhibition of cell wall synthesis. We consider the phenomenon a novel antimicrobial mode of action which provides valuable insight into the diverse mechanisms by which membrane-active peptides unfold their antimicrobial potential.

Methods

Peptide synthesis

As reported previously, the parent peptide cWFW was prepared by multiple solid-phase synthesis using an Fmoc/tBu strategy according to SHEPPARD51,52,53. Peptide purification and analysis were accomplished with high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a Jasco LC-2000Plus (Japan) and Dionex UltiMate 3000 with ProntoSil 300–5-C18-H columns (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) (Bischoff Chromatography, USA). Peptide mass was determined by UPLC-MS (ultra-performance liquid chromatography mass spectrometry) on an ACQUITY UPLC® System (Waters) using an Ascentis® Express Peptide ES-C18 column (3 × 2.1 mm, 2.7 μm) (Sigma-Aldrich). Final peptide purity was determined to be >95%. The labelled peptide derivative (FL-cWFW) containing 3-N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole-4-yl)-2,3-diamino-propionic acid (Dap-NBD) was purchased from Biosyntan GmbH, Berlin.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Cells were inoculated from an overnight culture 1:100 and grown to mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.2–0.4). Unless stated otherwise, all experiments were carried out in LB medium at 37 °C. Cell numbers were determined using a Petroff-Hausser counting chamber: OD600 = 1 corresponds to 8.8 × 107 CFU/ml B. subtilis. Further information on strains, conditions of gene induction, and minimal inhibitory concentration are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Construction of strains

For the construction of a B. subtilis strain expressing WALP23-GFP, the synthetic sequence encoding WALP2354 was constructed by annealing oligonucleotides WALP23-for and WALP23-rev, followed by PCR-filling the single-stranded regions. The resulting DNA-fragment was amplified using oligonucleotides WALP23-IFfor and WALP23-IFrev, and fused with plasmid pSG115455 PCR-linearised with oligonucleotides pSG1154-for and pSG154-rev using In-Fusion Cloning (Clontech). The final plasmid was integrated into amyE-locus of B. subtilis resulting in strain HS64. For the construction of a B. subtilis strain expressing GFP fused with JunLZ-dimerisation domain56 and a membrane-targeting sequence (MTS) of B. subtilis MinD57, junLZ-MinDMTS was PCR-amplified from a previously constructed E. coli plasmid pHJS10057 using oligonucleotides JunLZ-for and MTS-rev, followed by ligation into BamHI/HindIII-linearised E. coli-B. subtilis shuttle vector pSG172955. At last, the plasmid was integrated into amyE-locus of B. subtilis resulting in strain HS65. Transformation of B. subtilis 168 with either plasmid DNA or chromosomal DNA from donor strains was carried out as described in Hamoen et al.58. See Supplementary Table 5 for oligonucleotide sequences.

Antimicrobial activity

The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC), which is defined as the lowest concentration able to inhibit growth of a microorganism in vitro59, was analysed as described before60. Briefly, bacteria were grown to mid-log phase and diluted in growth medium to give a final cell number of 5 × 105 cells/well in 96 well microtiter plates. A microdilution technique was applied where small volumes of peptide solutions were added in a serial dilution ranging from 100 to 0.05 μM. Cells were cultivated for 18 hours, 37 °C, 180 rpm, followed by photometrical detection of the optical density using a microplate reader (Tecan). Peptide concentrations were tested in triplicates in three independent experiments.

Proteome analysis

B. subtilis 168/DSM402 was grown in chemically defined Belitzky minimal medium (BMM)61. Cultures were incubated at 37 °C under steady agitation. Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were determined as described previously62. In growth experiments, exponentially growing cultures were exposed to a concentration range of peptide (Supplementary Figure 1)62. For physiological stress experiments, concentrations were chosen that led to 50% reduction of the growth rate. For proteomic profiling, as well as for all follow up experiments performed under the same growth conditions, 8 μM cWFW were used.

Radioactive labelling of newly synthesised proteins and subsequent separation of the cytosolic proteome by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) was performed as previously described62. Analytical gel images were analysed as described by Raatschen & Bandow63 using Decodon Delta 2D 4.1 image analysis software. Proteins more than two-fold upregulated in three independent biological replicates were defined as marker proteins. Protein spots were identified by MALDI-ToF/ToF or nanoUPLC-ESI-MS/MS using a Synapt G2-S HDMS mass spectrometer equipped with a lock spray source for electrospray ionisation and a ToF detector (Waters) as previously reported (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3)62.

Membrane potential measurement

Peptide-induced changes in membrane potential were measured using the voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye DiSC3(5). In aqueous solution DiSC3(5) emits strong fluorescence which is quenched upon accumulation in polarised cells. Upon depolarisation, DiSC3(5) is released from the cell resulting in an increased fluorescence due to de-quenching. B. subtilis 168 was grown at 37 °C to mid-log phase and diluted in LB medium to OD600 0.2. After centrifugation for 1 min at 16,500 rpm, the supernatant was removed and cells carefully resuspended in 1 ml fresh pre-warmed LB containing 0.1 mg/ml BSA. Subsequently, 140 μl aliquots of the cell suspension were transferred into a 96 well microtiter plate and allowed to settle. 10 μl of 15 μM DiSC3(5) in LB/15% DMSO were added to the wells to give a final DiSC3(5) concentration of 1 μM. Cellular accumulation (quenching) of DiSC3(5) was monitored until the signal had reached stable fluorescence levels. The peptides were added at desired concentrations at 5 μl/well, and the resulting changes in DiSC3(5) fluorescence were analysed for at least 20 min using a Fluostar Optima, BMG Labtech. Solutions, plates and instruments were warmed to 37 °C prior to use.

ATP measurement

For the determination of cellular ATP levels samples were incubated with increasing concentration of cWFW for 20 min, followed by flash-freeze in liquid N2 in order to stop metabolism. Cell lysis and measurement of cell ATP levels were carried out using ATP bioluminescence Assay Kit HSII (Roche Applied Science) following manufacturer’s instructions using a BMG Fluostar Optima luminometer. The measured luminescence was calibrated with a serial dilution of ATP and triplicate samples were equalised against the optical density of the corresponding cell suspensions.

Ion analysis

Only metal-free plastic ware and ultrapure water (Bernd Kraft) were used. All centrifugation steps were reduced to 2 min to reduce sample handling time. Cultures were adjusted to OD500 = 0.4 prior to antibiotic exposure to ensure equal cell count in each sample. Samples were prepared as described by Wenzel et al.13. Briefly, B. subtilis 168/DSM402 was grown in BMM until early exponential growth phase. For determination of ion concentrations, subcultures were incubated with 8 μM cWFW for 15 min, followed by cell harvest by centrifugation, washed twice in TE buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) and once in the same buffer without EDTA. The obtained cell pellets were digested in 65% nitric acid (Bernd Kraft) at 80 °C for 16 h. Prior to element analysis, samples were diluted with ultrapure water to a final nitric acid concentration of 10%. Element concentrations were determined by inductively-coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy using an iCAP* 6300 Duo View ICP Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as described before13. Liquid calibration standards ranging from 10 μg/l to 10 mg/l of each element of interest (Fe, K, Mg, Mn, Na, S, P and Zn) (Bernd Kraft) were run before each series of measurements and selected standards were additionally run every 20 samples as quality control. Sulfur and phosphorus served as additional internal controls for cell mass. Element concentrations were converted into intracellular ion concentrations based on the B. subtilis cellular volume, which was taken as 3 × 10–9 μl based on average rod size determined by cryo-electron microscopy images by Matias and Beveridge64,65.

Membrane conductivity measurements

Free-standing planar lipid membranes were formed according to an established protocol66 from a 20 mg/mL solution of E. coli lipid (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, USA) in n-decane and spread across a circular aperture (Ø 150 μm) in a polysulfone bilayer cup between two aqueous phases in a bilayer chamber (both Warner Instruments, LLC, Hamden, USA). Transmembrane current was measured with Ag/AgCl electrodes and an Axon GeneClamp 500 amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, USA) under voltage-clamp conditions. A 4-pole Bessel with a 3-dB corner frequency of 500 Hz was used as recording filter. The amplified signal was digitised by a PCI 6025E computer board (National Instruments, Munich, Germany) and analysed with WinEDR (Strathclyde Electrophysiology Software, Strathclyde, UK). Membrane conductivity was calculated for zero-voltage from voltage-current dependencies of the steady-state current (recorded by application of ramp voltage from −100 to 100 mV). Peptides were added at both sides of the membrane (cWFW: 10 μM, KLA-1: 0.3 μM; buffer: 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM KCl, pH 7.4, 21–23 °C). Gaussian filters of 3–11 Hz were applied to reduce noise while data processing.

Membrane fluidity measurements

Membrane fluidity was investigated with the small hydrophobic fluorescent dye laurdan, which integrates into cellular membranes and detects changes related to the lipid packing of the surrounding bilayer67,68. The resulting changes in the fluorescence emission spectrum can be detected either spectroscopically or with fluorescence microscopy. A mathematical quantification of the emission shift is achieved by calculation of the laurdan GP (generalised polarisation) with GP = (I435 − I490)⁄(I435 + I490).

B. subtilis 168 cells were grown to OD600 ~ 0.5 in LB/0.1% glucose and incubated with 10 μM laurdan for 5 min, shaking in the dark. Subsequently, cells were washed 4 times in PBS/0.1% glucose, and 150 μl aliquots were transferred to a 96 well microtiter plate. The peptide was added at the desired final concentration at a maximum volume of 3 μl/well. The supernatant removed from the cells after the last washing step served as background for laurdan fluorescence not associated with cells. The solvent benzyl alcohol (BA) has a fluidising effect on lipid bilayers and was used as positive control (50 mM). All samples were shaken briefly before fluorescence detection at 435 ± 5 nm and 490 ± 5 nm (upon excitation at 350 ± 10 nm) on a plate reader (Fluostar Optima, BMG Labtech). Laurdan fluorescence was monitored for at least 20 min. Peptide influence on membrane fluidity was investigated in three independent experiments. Laurdan fluorescence in liposomes was recorded using an LS 50B spectrofluorometer (Perkin-Elmer Corp., Germany). Samples of 0.25 mM LUV suspension were continuously stirred during the experiment and temperature control was achieved by a built-in Peltier element. Laurdan fluorescence was detected separately at 435 and 500 nm, respectively. The average of three measurements for each preparation was calculated to determine corresponding laurdan GP values. See Scheinpflug et al.69 for detailed protocols and discussion of the laurdan-based fluidity measurements.

Liposome preparation

For in vitro analysis of membrane fluidity 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE), cardiolipin (CL, bovine brain), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3[phosphor-rac-(1-glycerol)] (POPG) and natural E. coli polar lipid extract were purchased from Avanti® Polar Lipids (Alabama, USA). Lipid powders were dissolved in chloroform/methanol (3/1) and individual components of binary mixtures were mixed in desired combinations: POPE/CL 87.5/12.5, POPE/PG 75/25. E. coli lipid extract was used as obtained. 0.2 mg/ml laurdan solution in chloroform was added to each lipid mixture giving a laurdan-to-lipid molar ratio of 1.5:1000. Large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) were prepared using a standard protocol5 by extrusion of lipid solution in phosphate buffer through two stacked polycarbonate filters (100 nm pore size) using a MiniExtruder (Avestin Europe, Germany). Vesicle size was ~110 nm, as determined by dynamic light scattering performed on a Zetasizer Nano ZS ZEN 3600 device (Malvern Instruments, UK). Aliquots were stored at −20 °C under argon atmosphere for replicate experiments. 1 mM lipid stock solutions were used for plain vesicles, while peptide-containing LUVs were prepared from 2 mM lipid stocks mixed with an equal volume of cWFW in phosphate buffer. Peptide concentration varied from 10 to 50 μM, corresponding to molar peptide-lipid ratios of P/L = 0.01 to 0.05. To obtain homogeneous peptide distribution the suspensions were vigorously vortexed and subjected to 1–2 cycles (5 min/cycle) in an ultrasonic bath. Vesicles were further extruded as described above. LUV size was 110–130 nm, depending on peptide-lipid molar ratio.

Fluorescence microscopy

Peptide-induced formation of lipid domains was visualized with the membrane dye nile red. The fluorescence of the dye is very low in polar solvents but strongly increases in hydrophobic environments. Nile red intensity is considered to be independent of the interaction with certain lipid head groups but is affected by the degree of membrane fluidity25. Cells were grown to mid-log phase, adjusted to OD 0.2 in growth medium and incubated with 12 μM peptide for 20 min, shaking. Microscope slides were covered with a thin layer of H2O/1.2% agarose and transferred to 8 °C for polymerisation (adjusted to room temperature prior to use). Nile red (final concentration of 1 μg/ml) was added to the cells immediately before imaging. Fluorescence microscopy was performed using Nikon Eclipse Ti (Nikon Plan Fluor 100x/1.30 oil ph3 DLL objective).

Peptide-induced protein delocalisation was investigated with B. subtilis strains expressing fluorescent fusion-proteins (see supplementary Table 4). For this aim, the cells were cultivated at 37 °C to early/mid-log phase, adjusted to OD600 of 0.2 in growth medium, and incubated with 12 μM cWFW for 20 min at 37 °C under shaking. Defects in cell wall synthesis were analysed after 15 min pre-incubation of B. subtilis wild type cells with 12 μM cWFW followed by addition of 0.5 μg/ml BODIPY-labelled vancomycin (FL-Van, Thermo Fisher Scientific) mixed with an equal concentration of unlabelled vancomycin for 5 min. Fluorescence imaging was performed as described above. All microscopy experiments were carried in biological triplicates.

Fatty acid analysis

The fatty acid composition of B. subtilis membranes was determined for cells grown at 37 °C in LB medium and for cells challenged with cWFW. Cell samples were withdrawn at comparable optical densities and upon re-initiation of growth of the cWFW-stressed cells in order to provide sufficient time for adaptation. The analysis was performed by conversion of lipids into fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) followed by gas chromatography. The analysis was carried out by the Identification Service of the DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Scheinpflug, K. et al. Antimicrobial peptide cWFW kills by combining lipid phase separation with autolysis. Sci. Rep. 7, 44332; doi: 10.1038/srep44332 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Janina Stautz and Kenneth H. Seistrup (Newcastle University) for strains, Ute Krämer (Ruhr University Bochum) for support with AES, Pascal Prochnow for assistance with mass spectrometry, colleagues at Rubion (Ruhr University Bochum) for technical support, and Seamus Holden and Heath Murray (Newcastle University) for critical reading of the manuscript. HS was supported by Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Funds (ISSF) grant 105617/Z/14/Z. JEB gratefully acknowledges funding from the German Federal State of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the European Union, European Regional Development Fund, “Investing in your future” (number 005-1007-0015) and for the mass spectrometer (Forschungsgroßgeräte der Länder).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions K.S., M.D. and H.S. designed the project, K.S., M.W., O.K. and H.S. carried out the experiments, K.S., O.K., M.D., M.W. and H.S. analysed the data and wrote the paper, J.E.B. provided input to the paper.

References

- Baltzer S. A. & Brown M. H. Antimicrobial peptides: Promising alternatives to conventional antibiotics. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20, 228–235 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelt C., Wessolowski A., Dathe M. & Schmieder P. Structures of cyclic, antimicrobial peptides in a membrane-mimicking environment define requirements for activity. J. Pept. Sci. 14, 524–527 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondelle S. E., Perez-Paya E. & Houghten R. A. Synthetic combinatorial libraries: Novel discovery strategy for identification of antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40, 1067–1071 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinpflug K., Nikolenko H., Komarov I., Rautenbach M. & Dathe M. What goes around comes around-a comparative study of the influence of chemical modifications on the antimicrobial properties of small cyclic peptides. Pharmaceuticals 6, 1130–1144 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junkes C. et al. Cyclic antimicrobial R-, W-rich peptides: The role of peptide structure and E. coli outer and inner membranes in activity and the mode of action. Eur. Biophys. J. 40, 515–528 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinpflug K., Krylova O., Nikolenko H., Thurm C. & Dathe M. Evidence for a novel mechanism of antimicrobial action of a cyclic R-,W-rich hexapeptide. PLoS One 10, e0125056 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand R. M. & Epand R. F. Lipid domains in bacterial membranes and the action of antimicrobial agents. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788, 289–294 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwani P. et al. Membrane-active peptides and the clustering of anionic lipids. Biophys. J. 103, 265–274 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arouri A., Dathe M. & Blume A. Peptide induced demixing in PG/PE lipid mixtures: A mechanism for the specificity of antimicrobial peptides towards bacterial membranes? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788, 650–659 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger S., Kerth A., Dathe M. & Blume A. The efficacy of trivalent cyclic hexapeptides to induce lipid clustering in PG/PE membranes correlates with their antimicrobial activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1848, 2998–3006 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M. & Bandow J. E. Proteomic signatures in antibiotic research. Proteomics 11, 3256–3268 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandow J. E., Brotz H., Leichert L. I., Labischinski H. & Hecker M. Proteomic approach to understanding antibiotic action. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 948–955 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M. et al. Small cationic antimicrobial peptides delocalize peripheral membrane proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, E1409–1418 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafuzzaman M., Andersen O. S. & McElhaney R. N. The antimicrobial peptide gramicidin s permeabilizes phospholipid bilayer membranes without forming discrete ion channels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778, 2814–2822 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezin S. K. Valinomycin as a classical anionophore: Mechanism and ion selectivity. J. Membrane Biol. 248, 713–726 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Te Winkel J. D., Gray D. A., Seistrup K. H., Hamoen L. W. & Strahl H. Analysis of antimicrobial-triggered membrane depolarization using voltage sensitive dyes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 4, 29 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dathe M. et al. General aspects of peptide selectivity towards lipid bilayers and cell membranes studied by variation of the structural parameters of amphipathic helical model peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1558, 171–186 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arouri A., Kiessling V., Tamm L., Dathe M. & Blume A. Morphological changes induced by the action of antimicrobial peptides on supported lipid bilayers. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 158–167 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. M. & Rock C. O. Membrane lipid homeostasis in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 222–233 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joanne P. et al. Lipid reorganization induced by membrane-active peptides probed using differential scanning calorimetry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788, 1772–1781 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salnikov E. S., Mason A. J. & Bechinger B. Membrane order perturbation in the presence of antimicrobial peptides by (2)h solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Biochimie 91, 734–743 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller A. et al. Daptomycin inhibits cell envelope synthesis by interfering with fluid membrane microdomains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA In Press (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber M. H., Klein W., Muller L., Niess U. M. & Marahiel M. A. Role of the Bacillus subtilis fatty acid desaturase in membrane adaptation during cold shock. Mol. Microbiol. 39, 1321–1329 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl H., Burmann F. & Hamoen L. W. The actin homologue MreB organizes the bacterial cell membrane. Nat. Commun. 5, 3442 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucherak O. A. et al. Switchable nile red-based probe for cholesterol and lipid order at the outer leaflet of biomembranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 4907–4916 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K., Kusaka J., Nishibori A. & Hara H. Lipid domains in bacterial membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 1110–1117 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer L. V. et al. Lipid packing drives the segregation of transmembrane helices into disordered lipid domains in model membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 1343–1348 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamurthi K. S., Lecuyer S., Stone H. A. & Losick R. Geometric cue for protein localization in a bacterium. Science 323, 1354–1357 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman R. et al. Structural and genetic analyses reveal the protein SepF as a new membrane anchor for the Z ring. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E4601–4610 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heijenoort J. Lipid intermediates in the biosynthesis of bacterial peptidoglycan. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71, 620–635 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errington J. Bacterial morphogenesis and the enigmatic MreB helix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel R. A. & Errington J. Control of cell morphogenesis in bacteria: Two distinct ways to make a rod-shaped cell. Cell 113, 767–776 (2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Typas A., Banzhaf M., Gross C. A. & Vollmer W. From the regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis to bacterial growth and morphology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 123–136 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohanski M. A., Dwyer D. J. & Collins J. J. How antibiotics kill bacteria: From targets to networks. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 423–435 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Cuevas P., Porcelli I., Daniel R. A. & Errington J. Differentiated roles for MreB-actin isologues and autolytic enzymes in Bacillus subtilis morphogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 89, 1084–1098 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kruijff B. Lipid polymorphism and biomembrane function. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1, 564–569 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevcsik E. et al. Interaction of LL-37 with model membrane systems of different complexity: Influence of the lipid matrix. Biophys. J. 94, 4688–4699 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov M., Dowhan W. & Vitrac H. Lipids and topological rules governing membrane protein assembly. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 1475–1488 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohner K. New strategies for novel antibiotics: Peptides targeting bacterial cell membranes. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 28, 105–116 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid R., Veleba M. & Kline K. A. Focal targeting of the bacterial envelope by antimicrobial peptides. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 4, 55 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand R. M., Walker C., Epand R. F. & Magarvey N. A. Molecular mechanisms of membrane targeting antibiotics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1858, 980–987 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T. & Sahl H. G. An oldie but a goodie - cell wall biosynthesis as antibiotic target pathway. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 300, 161–169 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M. et al. Proteomic response of Bacillus subtilis to lantibiotics reflects differences in interaction with the cytoplasmic membrane. Antimicrob. Agents Chemothe.r 56, 5749–5757 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sass V. et al. Human beta-defensin 3 inhibits cell wall biosynthesis in Staphylococci. Infect. Immun. 78, 2793–2800 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr A. K., Gooderham W. J. & Hancock R. E. W. Antibacterial peptides for therapeutic use: Obstacles and realistic outlook. Curr. Opin. Pharmac. 6, 468–472 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand R. M. & Epand R. F. Bacterial membrane lipids in the action of antimicrobial agents. J. Pept. Sci. 17, 298–305 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand R. F., Mor A. & Epand R. M. Lipid complexes with cationic peptides and oaks; their role in antimicrobial action and in the delivery of antimicrobial agents. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 68, 2177–2188 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweytick D. et al. N-acylated peptides derived from human lactoferricin perturb organization of cardiolipin and phosphatidylethanolamine in cell membranes and induce defects in Escherichia coli cell division. PLoS One 9, e90228 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingwood D., Kaiser H. J., Levental I. & Simons K. Lipid rafts as functional heterogeneity in cell membranes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 955–960 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grage S. L., Afonin S., Kara S., Buth G. & Ulrich A. S. Membrane thinning and thickening induced by membrane-active amphipathic peptides. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 4 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dathe M., Nikolenko H., Klose J. & Bienert M. Cyclization increases the antimicrobial activity and selectivity of arginine- and tryptophan-containing hexapeptides. Biochemistry 43, 9140–9150 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessolowski A., Bienert M. & Dathe M. Antimicrobial activity of arginine- and tryptophan-rich hexapeptides: The effects of aromatic clusters, d-amino acid substitution and cyclization. J. Pept. Res. 64, 159–169 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan W. & White P. In Practical approach 370 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- de Planque M. R. & Killian J. A. Protein-lipid interactions studied with designed transmembrane peptides: Role of hydrophobic matching and interfacial anchoring. Mol. Membr. Biol. 20, 271–284 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis P. J. & Marston A. L. GFP vectors for controlled expression and dual labelling of protein fusions in Bacillus subtilis. Gene 227, 101–110 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szeto T. H., Rowland S. L., Habrukowich C. L. & King G. F. The mind membrane targeting sequence is a transplantable lipid-binding helix. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 40050–40056 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl H. & Hamoen L. W. Membrane potential is important for bacterial cell division. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 12281–12286 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamoen L. W., Smits W. K., de Jong A., Holsappel S. & Kuipers O. P. Improving the predictive value of the competence transcription factor (comk) binding site in Bacillus subtilis using a genomic approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 5517–5528 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan K. J. & Sherris J. C. Sherris medical microbiology. 6. edn (Mc Graw-Hill, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand I., Hilpert K. & Hancock R. E. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (mic) of antimicrobial substances. Nat. Protoc. 3, 163–175 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stulke J., Hanschke R. & Hecker M. Temporal activation of beta-glucanase synthesis in Bacillus subtilis is mediated by the GTP pool. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139, 2041–2045 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M. et al. Proteomic signature of fatty acid biosynthesis inhibition available for in vivo mechanism-of-action studies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 2590–2596 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raatschen N. & Bandow J. E. 2-D gel-based proteomic approaches to antibiotic drug discovery. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. Chapter 1, Unit1F.2 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matias V. R. & Beveridge T. J. Cryo-electron microscopy reveals native polymeric cell wall structure in Bacillus subtilis 168 and the existence of a periplasmic space. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 240–251 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matias V. R. & Beveridge T. J. Lipoteichoic acid is a major component of the Bacillus subtilis periplasm. J. Bacteriol. 190, 7414–7418 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller P., Rudin D. O., Tien H. T. & Wescott W. C. Reconstitution of cell membrane structure in vitro and its transformation into an excitable system. Nature 194, 979–980 (1962). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris F. M., Best K. B. & Bell J. D. Use of laurdan fluorescence intensity and polarization to distinguish between changes in membrane fluidity and phospholipid order. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1565, 123–128 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez S. A., Tricerri M. A. & Gratton E. Laurdan generalized polarization fluctuations measures membrane packing micro-heterogeneity in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 7314–7319 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinpflug K., Krylova O. & Strahl H. In Antibiotics: Methods and protocols (ed Sass Peter) 159–174 (Springer New York, 2017). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.