Abstract

Background:

Cleft lip and palate (CLP) are the most common craniofacial birth impairment and one of the most common congenital impairments in humans. Anecdotal evidence suggests that stigmatization, discrimination, and sociocultural inequalities are common “phenomenon” experienced by families of children with CLP in Nigeria. This study aimed to explore the stigmatization, discrimination, and sociocultural inequalities experiences of families with children born with CLP.

Materials and Methods:

The study was carried out at the surgical outpatient cleft clinic of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria. This was a cross-sectional descriptive study among mothers of children born with CLP, using both interviewer-administered questionnaire and a semi-structured interview.

Results:

A total of 51 mothers of children with cleft lip and/or palate participated in the study. 35.3% of respondents believed cleft was an “act of God,” whereas others believed it was either due to “evil spirit” (5.9%), “wicked people” (9.8%). Seventy-three percent of the mothers were ashamed of having a child with orofacial cleft. Two of the respondents wanted to abandon the baby in the hospital. About a quarter of the respondent wished the child was never born and 59% of the fathers were ashamed of the facial cleft. Fifty-one percent admitted that their relatives were ashamed of the orofacial cleft, and 65% admitted that their friends were ashamed of the cleft. In addition, 22% of the respondents admitted that they have been treated like an outcast by neighbors, relatives, and friends because of the cleft of their children. When asked about refusal to carry the affected children by friends, relatives, and neighbors, 20% of respondents said “Yes.”

Conclusions:

Myths surrounding the etiology of orofacial cleft are prevalent in Nigeria. Parents and individuals with CLP experience stigma as well as social and structural inequalities due to societal perceptions and misconception about CLP. Public and health-care professionals must be equipped with necessary knowledge to combat stigma, discrimination, social and structural inequalities, and misconceptions associated with orofacial cleft. CLP should be considered a facial difference rather than a disability.

Keywords: Discrimination, inequalities, orofacial cleft, stigma

INTRODUCTION

The concept of stigma, denoting relations of shame, has a long ancestry and has from the earliest times been associated with deviations from the “normal,” including, in various times and places, deviations from normative prescriptions of acceptable state of being from self and others.[1] Stigma is typically a social process, experienced or anticipated, characterized by exclusion, rejection, blame or devaluation that result from experience, perception or reasonable anticipation of an adverse social judgment about a person or group.[2] This judgment is based on an enduring feature of identity conferred by a health problem or health-related condition, and the judgment is in some essential way medically unwarranted.[2] In addition to its application to persons or a group, the discriminatory social judgment may also be applied to the disease or designated health problem itself with repercussions in social and health policy. Other forms of stigma, which result from adverse social judgments about enduring features of identity apart from health-related conditions (e.g., race, ethnicity, sexual preferences), may also affect health; these are also matters of interest that concern questions of health-related stigma.[3] Some examples of stigmatized health conditions are epilepsy, leprosy, stuttering, and HIV infection, mental illness, alcoholism, podoconiosis, psoriasis.[3,4,5,6,7]

The human face is a corridor of emotions, a gateway to verbal and nonverbal communication, and a criterion for social acceptance and mate selection.[8] The esthetics of facial structure are used by humans to measure not only one's beauty but also his or her personality, intelligence, social class, trustworthiness, social skill, popularity, and overall “goodness.”[9] Orofacial cleft, due to its particular location in the orofacial region, can be particularly distressing; and parents of the affected children are usually ashamed/uncomfortable with bringing out their children in public. Congenital facial impairments remain a source of social and mental distress to the affected families.[10] In fact, cases of infanticide associated with cleft have been reported in the literature.[10,11]

In many cultures, the explanation for why a specific disability occurs is shared by all members of the community.[12] In diverse multicultural societies, the different cultures may sometimes reflect considerable variation in beliefs about disability and family life.[13,14] In a previous study on knowledge and cultural beliefs about the etiology of orofacial clefts in Nigeria, Oginni et al.[15] found that some respondents believed that traditional religion beliefs must have been violated for a defect like a cleft to have occurred. In fact, some respondents see orofacial clefts as an aftermath of eating certain food items that are forbidden, failure to fulfill some obligations such as eating and drinking relevant concoctions during pregnancy or stealing by either the father or mother.[15] Oftentimes, wrongdoings were traced to the mother who, according to the respondents, would be confronted with implicating and derogatory expressions such as “You are the only one that can explain where you got a child like this from;” “Your sin has found you out;” “We have never seen this in this family;” and “You must have bad eggs in your body,” among others.[15] In Hyderabad community, India, a commonly held belief is that cleft lip and palate (CLP) is caused by eclipse.[16]

Anecdotal evidence suggests that stigmatization/discrimination is a common “phenomenon” experienced by families of children with CLP impairment.[13,15] This stigma/discrimination can arise from family members, friends, community members, health-care workers, and even the affected parents (internalized stigma). Stigma is an obstacle to good health and barrier to health care for those shamed or blamed in developing as well as developed societies.[7] Stigma may be a significant contributor that erects real and perceived barriers to recovery.[6]

Individuals might be stigmatized due to real or perceived disability or impairment. Sociologists have also differentiated “disability” from “impairment.” Accordingly, impairment is considered as difficulty in physical, mental, and sensory functioning, whereas disability is how an impairment affects someone's life; this is determined by the extent to which society is willing to accommodate people with different needs.[17] There are two popular models of disability (social model and medical model). The social model asserts that “disability” is not caused by impairment but by the social barriers (structural and attitudinal) that people with impairments (physical, intellectual, and sensory) come up against in every arena.[18] The social model views disabled people as socially oppressed, and it follows that improvements in their lives necessitate the sweeping away of disablist social barriers and the development of social policies and practices that facilitate full social inclusion and citizenship.[18] In contrast, the medical model is based on the assertion that disability is caused by impairment.[18] In many cultures, including Nigeria, cleft impairment is considered a disability.[10,15,16]

The people who are disabled are frequently stigmatized.[19] According to Reidpath et al.,[19] the level of stigma experienced by those stigmatized is not consistent across cultures, and this inconsistency provides further evidence of the plausibility of the assertion that stigma is related to social value. What is the societal attitude toward cleft in Nigeria? Is CLP stigmatized in Nigeria?

Therefore, the aim of the study was to explore the stigmatization, discrimination, and social exclusion experienced by children born with CLP from family members, friends, and the community, as well as health-care givers in Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study among mothers of children born with CLP, using both interviewer-administered questionnaire and a semi-structured interview. The study was carried out at the surgical outpatient cleft clinic of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria.

Primary sources of data collection included questionnaire and semi-structured interview. A questionnaire [Appendix I] was administered by the interviewer (the researcher) on the selected respondents. The questionnaire consisted of three parts as follows:

First part: Consisted of demographic data (age, ethnicity, occupation, etc.) and type of cleft deformities, as well as knowledge, attitude, and beliefs about cleft deformities

Second part: Consisted of questions about stigma associated with the deformities and its typology

Third part: Consisted of opinions of mothers about ways and methods to reduce stigma associated with cleft deformities.

The questionnaire was administered in English. However, the questionnaire was translated into local languages for families who do not understand English. Immediately after the questionnaire was administered, each respondent was also interviewed using a “semi-structured interview” method. The interview guide is shown in Appendix II. The interview provided an opportunity to respondents to fully express themselves on the concept of stigma and trigger responses that were not covered in the questionnaire. Respondents were asked to narrate their experiences about acceptance/refusal of your family members, friends, and relatives to carry the affected child (Item 1). In addition, they were asked to narrate their experiences about the attitude of their caregivers (doctors, nurses, medical record staff, etc.) toward them and the affected child (Item 2). Respondents were also asked to narrate any other bad experiences they have had due to the facial deformity of the affected child (Item 3). Responses to Items 1, 2, and 3 of the interview guide were recorded verbatim.

Ethical approval for the study was sought from the Health Research and Ethics Committee of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital before the commencement of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from each respondent before inclusion into the study.

Data analysis

Data collected with questionnaire was analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively. Data analysis is presented in descriptive and tabular formats. Verbatim record of the interview was analyzed for thematic analysis. The analysis started with coding for developing themes within the raw data by recognizing important moments in the data and encoding it before interpretation.

RESULTS

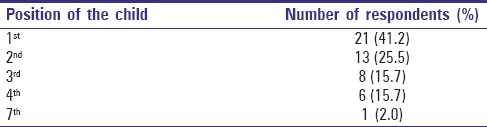

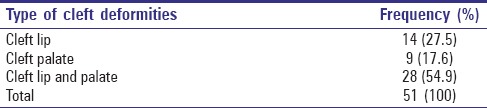

A total of 51 mothers of children with cleft lip and/or palate impairment participated in the study. The ages of the mother ranged between 20 and 43 years (mean ± standard deviation = 29.3 ± 5.4 years). In 41.2% of the respondents, the child was the first born of the family [Table 1]. The most common type of orofacial cleft deformity in children of respondents was CLP which was seen in 28 (54.9%) of the 51 children [Table 2].

Table 1.

Position of the child with cleft in the family

Table 2.

Type of orofacial cleft

Views, beliefs, and opinions on orofacial cleft

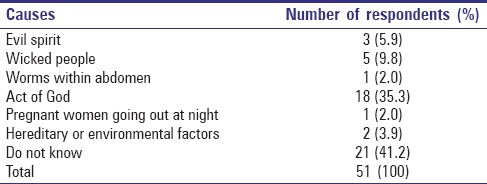

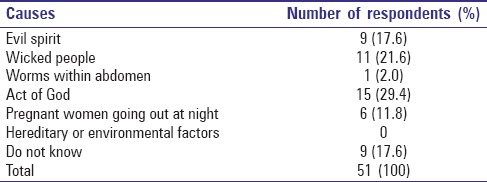

When respondents were asked about the cause(s) of the cleft of their children, majority (41.2%) of them did not know the cause, but a large number (35.3%) believed it was an “act of God” [Table 3]. Other reasons given were “evil spirit,” “wicked people” etc. Table 4 shows the beliefs of respondents’ family members on the causes of cleft deformities. Although majority of the family members believe in “act of God” as the cause of the deformities, a large percentage (39.2%) of them believed that “evil spirit” and “wicked people” are the main causes of the deformities [Table 4]. None of the family members believe in the hereditary/environmental factor as the factor responsible for the defect.

Table 3.

Beliefs about the causes of cleft according to respondents

Table 4.

Beliefs about the causes of cleft according to respondents’ family

Societal barriers and stigma toward cleft

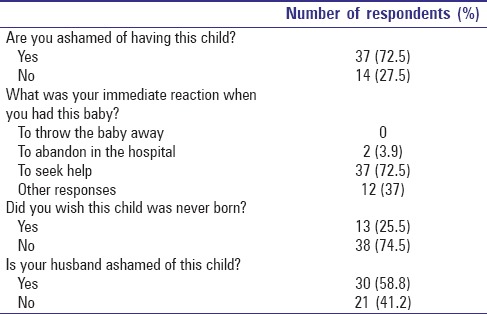

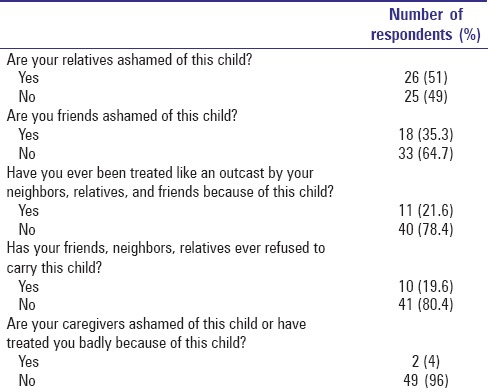

About 72% of the mothers were ashamed of having a child with cleft deformities [Table 5]. Although the question was negative, many mothers (72.5%) responded positively by seeking help, and a higher number of mothers (74.5%) were more positive about having their child [Table 5]. However, two of the respondents wanted to abandon the baby in the hospital. None of the respondents wished to throw the baby away. About a quarter of the respondent wished the child was never born [Table 5]. Thirty (58.8%) of the respondents claimed that their spouses were ashamed of having a child with cleft deformity [Table 5]. One of the respondents did everything possible to prevent friends, family members, and neighbors from seeing the affected child weeks after birth. Twenty-six (51%) of the respondents admitted that their relatives were ashamed of their affected children, and 33.3% admitted that their friends were ashamed of their children [Table 6]. In addition, 21.6% of the respondents admitted that they have been treated like an outcast by neighbors, relatives, and friends because of their affected children. When asked about refusal to carry the affected children by friends, relatives, and neighbors, 19.6% of respondents said “Yes” [Table 6]. Only two [Table 6] respondent said “Yes” when asked about the stigmatization of the affected child by the caregivers (doctors, nurses).

Table 5.

Response of the mothers to felt stigma-related questions

Table 6.

Response of the mothers to enacted stigma-related questions

When respondents were asked in an interview to narrate their experience on the stigma associated with their children defects, the responses are captured below:

Attitudes of family, friends, and relatives

When respondents were asked about the attitude of family and friends, twelve of them claimed to have experienced cruelty at the hands of their friends and relatives. One of the respondents said: “neighbors refuse to carry my child and making jest of her.” A mother were also blamed (“My in-laws refused to carry my baby the last time we went home for Christmas, claiming I was the cause of the defect because of my way of life”), mothers were also shunned and isolated (“My in-laws have refused to visit me since they heard about the birth of my child”) because they had a child who was viewed as less than “perfect.”

Attitudes of caregivers

There was no negative remark from respondents about the attitude of their caregivers toward the child and the mother. Phrases such as “caring and supportive,” “nice and friendly”, and “very supportive” were used by the respondents.

Mother's experiences of responses to their child

Sixteen parents described additional bad experiences of societal responses to their child. Five of them described issues with their partners and his families: “My husband has refused to care for my baby and my other children after the birth of this baby.” “My husband's family warned him not to marry me because of where I come from. “Since the birth of this child, they have made life miserable for me.” “My mother-in-law was very angry with me for having this child. She once said that I was the first to give birth to “a child like this” in their family.” “Sometimes my husband is sad and become moody about this baby. This makes me sad also.” “The father of my baby abandoned me and my baby the moment he saw the child with the cleft.” The above experiences can be interpreted as societal attitudes creating a blaming position toward parents.

Other parents also described what may be interpreted as social isolation and exclusion due to societal attitudes: “I had to hide the baby inside the house. The naming ceremony has been postponed indefinitely because of the defect.” “I have never been comfortable taken my baby out.” “I had to stay away from home the day the baby was being named because of shame.”

DISCUSSION

This study identified that most respondents claimed they do not know the cause of orofacial cleft, an appreciable number of them attributed cleft to an “act of God”, few others believed clefts were due to “evil spirit”, “wicked people”, and “pregnant women going out at night”. In a study on the cultural perception of the etiology of cleft, Oginni et al.[15] reported that most respondents (46.1%) claimed they did not know the cause of the clefts, 19.4% and 13.1% believed the clefts were due to evil spirit and an “act of God”, respectively. Olasoji et al.[13] compared the cultural difference in the perceived causes of cleft between Yoruba and Hausa ethic groups. While most Hausa respondents believed in “an act of God,” most Yoruba respondents perceived cleft to be due to “evil spirit” and “Ancestors punishment related to wrong doing by family.”[13]

Some Nigerians have also been reported to believe that there must be a curse at work and that the problem could have ancestral origin.[15] This idea of ancestral origin (something spiritual wished on us by our ancestors) has also been reported in Filipinos and Chinese.[20]

Family members, friends, and neighbors have been reported to play a significant role with regard to well-being of children with CLP.[16] In the present study, more family members were reported to have inferred that cleft is due to “evil spirit” and “wicked people” than mothers (respondents) of the children themselves. Penn et al.[21] explored the role of grandmothers, specifically in South African communities and found that grandmothers have a pivotal role in how various childhood disabilities are viewed and how children with these disabilities are treated. Of note, grandmothers in the studied community are recognized to have the authority to recommend infanticide.[21] It is noteworthy that one of the respondents in the present study claimed that her mother-in-law once said that she was the first to give birth to “a child like this” in their family. In Nigeria, family system rather than individualism is the prevailing culture, therefore the importance of family, friends, and neighbors in combating discrimination/stigma against orofacial cannot be overemphasized.

Typology and sources of stigma

Stigma, denoting relations of shame is typically a social process, experienced or anticipated, characterized by exclusion, rejection, blame or devaluation that result from experience, and perception or reasonable anticipation of an adverse social judgment about a person or group.[2] Stigma is also considered a social process through which individuals are devalued on the basis of particular negatively perceived characteristics or status.[22] Despite the fact that birth defects especially within and around the orofacial region are frequently stigmatized in our environment, little is known about the typology and sources of stigma associated with CLP deformities. Stigma may be a significant contributor that erects real and perceived barriers to recovery.[6] The presence of cultural stigma toward children with orofacial clefts may serve as a barrier to treatment and may directly threaten the safety of the child. Combating stigma is thus widely recognized as a key ingredient in the struggle against chronic stigmatizing illnesses and for improvements in public health in general.[23]

In the present study, various type of stigma, discrimination, and social isolation toward children with CLP was identified. Regarding the stigma, these were felt stigma, enacted stigma, felt normative stigma, and internalized stigma. About 73% of mothers and 59% of fathers were ashamed to have children with cleft deformities. This is considered either a felt stigma and/or internalized stigma. Felt stigma denotes both a sense of shame and a companion fear of encountering enacted stigma.[3] According to Scambler,[3] when confronted with a medical diagnosis of stigmatizing condition, state-sanctioned, culturally authoritative and carrying legal weight, individuals develop a “special view of the world” – characterized by a strong sense of felt stigma and predisposing them to secrecy and concealment. This is exemplified by the fact that about 4% of the mothers wanted to abandon the baby in the hospital/place of birth, and 26% of them also wished the child was never born. Felt stigma is typically more disruptive of the lives of the sufferer than enacted stigma.[24] Internalized stigma results in prejudice and may lead to enacted stigma; when it is internalized by putative possessors of stigma the consequence is “self-stigma.” In internalized stigma, people's self-concept is congruent with the stigmatizing responses of others; they accept the discredited status as valid.[25] A father, according to one of the respondents, was so internalized stigmatized to the point that he abandoned his wife and all the children after the birth of the affected child. One of the respondents exhibited a felt normative stigma by doing everything possible to prevent friends, family members, and neighbors to see the child weeks after birth. Felt normative stigma refers to a subjective awareness of stigma which it is expected will motivate individuals to take action to avoid enacted stigma.[25]

Enacted stigma refers to overt discrimination against those with stigmatizing conditions on the sole grounds of their social unacceptability.[3,26] Enacted stigma toward children born with CLP was very common in this study. Relatives, friends, and neighbors were reported to have behaved in a way suggestive of enacted stigma. Respondents reported that 51% and 35% of their relatives and friends, respectively, were ashamed of their baby born with orofacial cleft. In fact, about 20% of them reported that they have been treated like outcast due to the defects of their children. Refusal to carry babies born with orofacial cleft, a feature suggestive of enacted stigma was also very common.

During an interview session, one of the respondents reported that her mother-in-law accused her of being the cause of the deformity; a comment suggestive of symbolic stigma. Symbolic stigma connotes passing a negative moral judgment on individuals with a chronic stigmatizing condition. Maughan-Brown[22] identified symbolic stigma as one of the three distinct dimensions of HIV-AIDS-related stigma.

The previous researches into stigma associated with HIV-AIDS and epilepsy have also identified enacted stigma, felt stigma, felt normative stigma, and internalized stigma as common phenomenon among people living with these chronic conditions.[3,24,25]

Studies on the concept of health-related stigmatization have shown that there are several sources of health-related stigma (Slade et al., 2009; Thompson et al., 2010). Stigma has been reported to arise from external sources such as health-care professionals, the workplace, family and friends, the community, government agencies and insurance companies, and from other sufferers. Stigma can also arise from within, with sufferers experiencing guilt and blaming themselves for their experience.[6,27] In the present study, sources of stigma included friends, relatives, neighbors, and even respondents themselves. These identified sources have also been documented in other chronic stigmatizing conditions/illnesses such as epilepsy, mental illness, HIV-AIDS, podoconiosis, leprosy, and stuttering.[23,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]

It is instructive to note that there was no negative remark from respondents about the attitude of their caregivers toward the child or the mother. The importance of health-care workers as societal role models in terms of influencing societal attitudes and beliefs is very important. It has been documented that when patients are satisfied with the health-care encounter and trust them, they adhere to advise and this may assist treatment effectiveness.[35] Trust is always an important factor in patient–caregiver relationship. Trust has traditionally been considered a cornerstone of effective doctor–patient relationships.[36] The need for interpersonal trust relates to the vulnerability associated with being ill, the information asymmetries arising from the specialist nature of medical knowledge, and the uncertainty and element of risk regarding the competence and intentions of the practitioner on whom the patient is dependent.[36] According to Rowe and Calnan[36] without trust patients may well not access services at all, let alone disclose all medically relevant information.

It must also be stated here that the concept of stigma is still very controversial and not as simplistic as presented by authors such as Goffman[1] and Scambler.[3,26] Reidpath et al.[19] highlights why using stigma instead of discrimination may not be helpful and why a shift is necessary. Sayce[37] also gives a good account as to why stigma is not useful in all contexts. According to Sayce,[37] the concept of stigma unnecessarily limits the scope of discussion of what is possible. It creates a focus on individual attitude, rather than structural change. It advocates, first, changing stigmatized conceptions of themselves, and only second, addressing the conceptions of the public through education. According to Sayce,[37] terms such as “discrimination” and “exclusion” are more likely to help us conceptualize and plan this work than “stigma.” In addition, Oliver[38] in his discussion on politics of disablement argues that disabled people have not found stigma a useful concept because it has been unable “to throw off the shackles of the individualistic approach to disability with its focus on the discredited and the discreditable.” The legacy of Goffmann's work on stigma,[1] he argues, has been a focus on individual self-perception, and microlevel interpersonal interactions, rather than widespread and patterned exclusion from economic and social life.[38] “Stigma” has not provided a rallying point for collective strategies to improve access or challenge prejudice. Instead, the disability movement has turned to structural notions of discrimination and oppression.[38] On the one hand, whether one uses stigma, discrimination, or exclusion to describe the experience of parents of children born with CLP, it should be understood that the concept described in this paper is partly about CLP and the social barriers (structural and attitudinal) that individual with CLP come up against in the society as described by Thomas.[18] An alternatively idea to the above was proposed by Shakespeare[39] that disability occurs when there is an interaction of “individual” and “social” factors. According to Shakespeare (2006),[39] the experience of a disabled person results from the relationship between factors intrinsic to the individual, and extrinsic factors arising from the wider context, in which he/she finds herself. Among the intrinsic factors are issues such as the nature and severity of her impairment, his/her own attitudes to it, his/her personal qualities and abilities, and his/her personality. Among the contextual factors are the attitudes and reactions of others, the extent to which the environment is enabling or disabling, and wider cultural, social and economic issues relevant to disability in that society.[39] Individual perception of himself/herself is to a large extent a product of his/her make-up as well as the make-belief of his/her environment. Based on the result of the present study, and in line with the opinion expressed by Shakespeare (2006),[39] CLP disability results from the interplay of individual and contextual factors. In order words, people are disabled by society and by their bodies.

Strategies for combating discrimination, social isolation, and stigma associated with cleft lip and palate

Despite widespread awareness of the negative impact of social discrimination and stigma, advances in public health programs to address them have been comparatively slow and unsystematic.[40] The negative effect of discrimination and stigma is all encompassing involving the individuals affected, their relatives, friends, immediate community, and also has impact on the assessment of health facilities by the affected. In the present study, when respondents were asked about strategies to combat the menace, most of them (71%) believed that public awareness about the causes and prevention of cleft deformities is imperative. Awareness campaign by health-care professionals among mothers during prenatal period was also identified as a veritable tool to reduce stigma associated with the deformity.

To eradicate discrimination and stigma, the structural forces that drove them in the first instance must be taken into account.[41] Kurzban and Leary[42] made a distinctly sociobiological formulation of stigma, regarding stigmatization as a mechanism that has evolved for the purpose of excluding those people who reduced the fitness of the community. One common type of stigma reduction intervention is the information, education, and communication (IEC) campaign.[43] Such IEC campaigns have been developed as a means of reducing the level of stigma in diverse areas of health-related stigma such as epilepsy (Baker and Jacoby 2001), communicative disorders,[44] and congenital abnormalities.[45] According to Reidpath et al.,[19] these are conservative interventions, however, underpinned by a view that those who stigmatize have the agentive capacity to behave differently, and that knowledge is all that stands in the way of the behavior change. Hyland (2000)[46] has shown that effect of IEC campaign is unsatisfactory, particularly at a population level because the sociocultural forces that gave rise to the stigma are slow to subside even in the presence of knowledge (Hyland 2000).[46] Government and its activities are pervasive; therefore, the Government of Nigeria has a role to play in reducing discrimination, social isolation, and stigma associated with the birth of a child with CLP.

In a study on stigma experienced by people with nonspecific chronic low back pain, participants suggested the followings as practical ways to reduce stigma: public and health professional education, encouragement from people who have had recovery and success as well as participation in support groups.[6] Other authors[6,47] have also reported that formation of support groups and participation of those affected help in resisting negative feelings associated with stigmatization, and victim blaming advocacy group by parents of children with CLP may also go a long way in reducing the discrimination and social isolation.

CONCLUSIONS

Myths surrounding the etiology of orofacial cleft are prevalent in Nigeria. The findings of this study suggest that there is a need for community intervention aimed at dispelling myths and raising awareness about the etiology and available treatment opportunities for children born with CLP. Various types of stigma, discrimination, and social isolation toward children with CLP were also identified. Strategies to combat discrimination, exclusion, social isolation, and stigmatization must be put in place in Nigeria. To eradicate stigma, discrimination and exclusion associated with CLP efforts must not only be focused on the society (extrinsic factor) but also on the affected individuals whose perception about CLP has been defined by the society at large. Individuals with CLP should be considered as people with facial difference rather than people with disability.

Financial support and sponsorship

This paper was present as a poster at the 71st Annual Meeting and Symposia of the American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association (ACPA), March 24–29, 2014, Indianapolis, USA.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the families who voluntarily participated in this study and resident doctors who recruited children for this study. This project was partly supported by grants from the NIDCR K99/R00 DE022378 [AB].

APPENDICES: Questionnaire (Appendix I)

Stigmatization of children born with cleft lip and palate deformities: Challenges and prospects

Dear participant,

The purpose of this survey is to explore the stigmatization experienced by families with children born with cleft lip and palate deformities from family members, friends, and the community, as well as health-care givers.

Demographic data

Your age:....................................

Place of residence:.........................................................

-

Ethnicity:

- Yoruba

- Hausa

- Igbo

- Others (state)........................................................

Number of children:.....................................................

Occupation:...................................................................

Position of the child with cleft in the family:.............................

Type of cleft

Cleft lip only

Cleft lip and palate

Cleft palate only

Please answer the following questions:

-

What do you think caused your child's cleft (deformity)?

- Evil spirit

- Causes from wicked people

- Worms within the abdomen when denied food during pregnancy

- Act of God

- Pregnant women laughing at a patient with cleft lip and palate

- Pregnant women going out at night

- Hereditary or environmental factors

- Any other reasons:..........................................................

-

What do other members of your family/relations/friends say caused it?

- Evil spirit

- Causes from wicked people

- Worms within the abdomen when denied food during pregnancy

- Act of God

- Pregnant women laughing at a patient with cleft lip and palate

- Pregnant women going out at night

- Hereditary or environmental factors

- Any other reasons:..........................................................

Are you ashamed of having this child? .Yes .No

-

What was your immediate reaction when you had this baby?

- To throw the baby away

- To abandon in the hospital/other place(s) of birth

- To seek help

- Others (please state):...............................................

-

After the birth of this child and you noticed the defect, did you wish this child was never born?

- .Yes .No

-

Is your husband ashamed of this child?

- .Yes .No

-

Are your relatives ashamed of this child?

- .Yes .No

-

Are you friends ashamed of this child?

- .Yes .No

-

Have you ever been treated like an outcast by your neighbors, relatives, and friends because of this child?

- .Yes .No

-

Has your friends, neighbors, relatives ever refused to carry this child?

- .Yes .No

-

Do you have any reason to believe that your caregivers (doctors, nurses, medical record staff, etc.) are ashamed of this child or have treated you badly because of this child

- .Yes .No

-

What in your opinion needs to be done by health workers, public, government, and media houses to reduce the stigma (shame) associated with this kind of deformities?

- Public awareness about the causes and prevention of the deformity

- Awareness campaign among mothers during prenatal period

- Government has a role in reducing stigma associated with this condition

- Any other suggestions.....................................................................

Interview Guide (Appendix II)

Stigmatization of children born with cleft lip and palate deformities: Challenges and prospects

-

Kindly narrate your experience on the acceptance/refusal of your family members, friends and relatives to carry this child (refer question 10 above)

..........................................................................................................................................................................................

..........................................................................................................................................................................................

..........................................................................................................................................................................................

..........................................................................................

-

Kindly narrate your experience about the attitude of your caregivers (doctors, nurses, medical record staff, etc.) toward you and your child (refer question 11 above)

..........................................................................................................................................................................................

..........................................................................................................................................................................................

..........................................................................................................................................................................................

.................................................................................

-

Kindly narrate any other bad experiences you have had due to the facial deformity of this child:

..........................................................................................................................................................................................

..........................................................................................................................................................................................

..........................................................................................................................................................................................

..........................................................................................

REFERENCES

- 1.Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheyett A. The mark of madness: Stigma, serious mental illness and social work. Soc Work Ment Health. 2005;3:79–97. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scambler G. Epilepsy. London: Tavistock; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fortney J, Mukherjee S, Curran G, Fortney S, Han X, Booth BM. Factors associated with perceived stigma for alcohol use and treatment among at-risk drinkers. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2004;31:418–29. doi: 10.1007/BF02287693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corrigan PW, Lurie BD, Goldman HH, Slopen N, Medasani K, Phelan S. How adolescents perceive the stigma of mental illness and alcohol abuse. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:544–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.5.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slade SC, Molloy E, Keating JL. Stigma experienced by people with nonspecific chronic low back pain: A qualitative study. Pain Med. 2009;10:143–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scambler G. Health-related stigma. Sociol Health Illn. 2009;31:441–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fink B, Neave N. The biology of facial beauty. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2005;27:317–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.2005.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langlois JH, Kalakanis L, Rubenstein AJ, Larson A, Hallam M, Smoot M. Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:390–423. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akinmoladun VI, Owotade FJ, Afolabi AO. Bilateral transverse facial cleft as an isolated deformity: Case report. Ann Afr Med. 2007;6:39–40. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.55730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iregbulem LM. The incidence of cleft lip and palate in Nigeria. Cleft Palate J. 1982;19:201–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harwood A. Ethnicity and Medical Care. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olasoji HO, Ugboko VI, Arotiba GT. Cultural and religious components in Nigerian parents’ perceptions of the aetiology of cleft lip and palate: Implications for treatment and rehabilitation. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45:302–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauss RP. Culture, rehabilitation, and facial birth defects: International case studies. Cleft Palate J. 1985;22:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oginni FO, Asuku ME, Oladele AO, Obuekwe ON, Nnabuko RE. Knowledge and cultural beliefs about the etiology and management of orofacial clefts in Nigeria's major ethnic groups. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2010;47:327–34. doi: 10.1597/07-085.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naram A, Makhijani SN, Naram D, Reddy SG, Reddy RR, Lalikos JF, et al. Perceptions of family members of children with cleft lip and palate in Hyderabad, India, and its rural outskirts regarding craniofacial anomalies: A pilot study. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2013;50:e41–6. doi: 10.1597/10-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shakespeare T. Facing up to disability. Community Eye Health. 2013;26:1–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas C. Disability: Getting it “right”. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:15–7. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.019943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reidpath DD, Chan KY, Gifford SM, Allotey P. ‘He hath the French pox’: Stigma, social value and social exclusion. Sociol Health Illn. 2005;27:468–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2005.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng LR. Asian-American cultural perspectives on birth defects: Focus on cleft palate. Cleft Palate J. 1990;27:294–300. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569(1990)027<0294:aacpob>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penn C, Watermeyer J, MacDonald C, Moabelo C. Grandmothers as gems of genetic wisdom: Exploring South African traditional beliefs about the causes of childhood genetic disorders. J Genet Couns. 2010;19:9–21. doi: 10.1007/s10897-009-9252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maughan-Brown B. Stigma rises despite antiretroviral roll-out: A longitudinal analysis in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:368–74. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aggleton P, Parker R. A conceptual framework and basis for action: HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination. Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2003. World AIDS campaign 2002–2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider J, Conrad P. In the closet with illness: Epilepsy, stigma potential and information control. Soc Probl. 1980;28:32–44. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steward WT, Herek GM, Ramakrishna J, Bharat S, Chandy S, Wrubel J, et al. HIV-related stigma: Adapting a theoretical framework for use in India. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:1225–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scambler G, Hopkins A. ‘Being epileptic’: Coming to terms with stigma. Sociol Health Illn. 1986;8:26–43. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson AR, Clarke SA, Newell RJ, Gawkrodger DJ Appearance Research Collaboration (ARC) Vitiligo linked to stigmatization in British South Asian women: A qualitative study of the experiences of living with vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:481–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Awaritefe A, Ebie JC. Complementary attitudes to mental illness in Nigeria. Afr J Psychiatry. 1975;1:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neves DP. Alcoholism: Indictment or diagnosis? Rep Public Health. 2004;20:7–14. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2004000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Room R. Stigma, social inequality and alcohol and drug use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24:143–55. doi: 10.1080/09595230500102434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dodor EA. Health professionals expose TB patients to stigmatization in society: Insights from communities in an urban district in Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2008;42:144–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tekola F, Bull S, Farsides B, Newport MJ, Adeyemo A, Rotimi CN, et al. Impact of social stigma on the process of obtaining informed consent for genetic research on podoconiosis: A qualitative study. BMC Med Ethics. 2009;10:13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ronzani TM, Higgins-Biddle J, Furtado EF. Stigmatization of alcohol and other drug users by primary care providers in Southeast Brazil. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:1080–4. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Audu IA, Idris SH, Olisah VO, Sheikh TL. Stigmatization of people with mental illness among inhabitants of a rural community in Northern Nigeria. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2013;59:55–60. doi: 10.1177/0020764011423180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liddle SD, Baxter GD, Gracey JH. Chronic low back pain: Patients’ experiences, opinions and expectations for clinical management. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1899–909. doi: 10.1080/09638280701189895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowe R, Calnan M. Trust relations in health care – The new agenda. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16:4–6. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sayce L. Stigma, discrimination and social exclusion: What's in a word? J Ment Health. 1998;7:331–41. doi: 10.1080/09638239817932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oliver M. The Politics of Disablement. Basingstoke: MacMillan; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shakespeare T. Debating disability. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:11–4. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.019992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Brakel WH. Measuring health-related stigma – A literature review. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11:307–34. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kleinman A. Experience and its moral modes: Culture, human conditions, and disorder. In: Peterson GB, editor. The Tanner Lectures on Human Values. Utah: University of Utah Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kurzban R, Leary MR. Evolutionary origins of stigmatization: The functions of social exclusion. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:187–208. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benjamin C. Aspects of stigma associated with genetic conditions. In: Mason T, Carlisle C, Watkins C, Whitehead E, editors. Stigma and Social Exclusion in Health Care. London: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McArdle E. Communication impariment and stigma. In: Mason T, Carlisle C, Watkins C, Whitehead E, editors. Stigma and Social Exclusion in Health Care. London: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farrell M, Corrin K. The stigma of congenital abnormalities. In: Mason T, Carlisle C, Watkins C, Whitehead E, editors. Stigma and Social Exclusion in Health Care. London: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hyland J. Leprosy and social exclusion in Nepal: The continuing conflict between medical and socio. cultural beliefs and practices. In: Hubert J, editor. Madness, Disability and Social Exclusion: The Archaeology and Anthropology of Difference. London: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chapple A, Ziebland S, McPherson A. Stigma, shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: Qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328:1470. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38111.639734.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]