Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by memory loss, multiple cognitive abnormalities and intellectual impairments. Currently, there are no drugs or agents that can delay and/or prevent the progression of disease in elderly individuals, and there are no peripheral biomarkers that can detect AD early in its pathogenesis. Research has focused on identifying biomarkers for AD so that treatment can be begun as soon as possible in order to restrict or prevent intellectual impairments, memory loss, and other cognitive abnormalities that are associated with the disease. One such potential biomarker is microRNAs that are found in circulatory biofluids, such as blood and blood components, serum and plasma. Blood and blood components are primary sources where miRNAs are released in either cell-free form and then bind to protein components, or are in an encapsulated form with microvesicle particles. Exosomal miRNAs are known to be stable in biofluids and can be detected by high throughput techniques, like microarray and RNA sequencing. In AD brain, enriched miRNAs encapsulated with exosomes crosses the blood brain barrier and secreted in the CSF and blood circulations. This review summarizes recent studies that have identified miRNAs in the blood, serum, plasma, exosomes, cerebral spinal fluids, and extracellular fluids as potential biomarkers of AD. Recent research has revealed only six miRNAs–miR-9, miR-125b, miR-146a, miR-181c, let-7g-5p, and miR-191-5p – that were reported by multiple investigators. Some studies analyzed the diagnostic potential of these six miRNAs through receiver operating curve analysis which indicates the significant area-under-curve values in different biofluid samples. miR-191-5p was found to have the maximum area-under-curve value (0.95) only in plasma and serum samples while smaller area-under-curve values were found for miR-125, miR-181c, miR-191-5p, miR-146a, and miR-9. This article shortlisted the promising miRNA candidates and discussed their diagnostic properties and cellular functions in order to search for potential biomarker for AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, circulatory microRNA, biomarker, serum, cerebral spinal fluid, CSF, plasma

Introduction

Since the discovery of microRNA (miRNA) in C. elegance by Lee and colleagues in 1993, the role of miRNAs in various cellular processes has been established, including development, cell proliferation, replicative senescence, and aging [1–3]. According to the miRbase-21 database released in June 2014, 1881 precursor and 2588 mature miRNAs have been identified (www.mirbase.org/) in such human diseases as cancer, viral infection, diabetes, immune-related diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders [4–7]. miRNA biogenesis initiates in the nucleus with transcription of the primary miRNA transcript and with several processing steps, and it ends in the cytoplasm with the formation of mature miRNA molecules [8]. In human genome approximately 2000 genes encodes multiple miRNAs that target nearly 60% of all human genes in a sequence-specific manner and modulates gene expression either by mRNA degradation or repression [1, 9–10]. Besides their role as modulator of cellular activity, in pathological and non-pathological states, miRNAs are also released from the cells and enter into circulatory bio-fluids, such as the blood, serum, plasma, saliva, and urine [2, 11]. This peripheral circulatory form of miRNAs may be a very important bio-indicator for disease assessment. These circulatory miRNAs have also been found to be quite stable in extracellular circulation, suggesting that they can be used as biomarkers for various human diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, aging, and neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [5,11–14].

AD is a progressive degenerative disorder manifested by dementia in aged individuals [15–16]. Currently, over 46.8 million people live with dementia worldwide, and this number is estimated to increase to 131.5 million by 2050 [17]. Dementia has a huge economic impact. The total estimated worldwide medical cost of dementia in 2015 was $818 billion, and it will become a trillion-dollar disease by 2018 [17]. AD is associated with the loss of synapses, synaptic dysfunction, mitochondrial structural and functional abnormalities, inflammatory responses, and neuronal loss, in addition to extracellular neuritic plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles [17–21]. Several factors, including lifestyle, diet, environmental exposure, Type 2 diabetes, stroke, apolipoprotein allele E4, and several other genetic variants, are known to be involved in late-onset AD [22–23]. Early onset AD is associated genetic mutations in the amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1, and presenilin 2 [20].

Several decades of intense research have revealed that multiple cellular changes are involved in development and pathogenesis of disease, including mitochondrial damage, synaptic loss, amyloid beta accumulation, hyperphosphorylated tau formation, inflammatory responses, hormonal imbalance and cell cycle deregulation [17–19,21,24]. Therapeutic strategies have been developed, based on these cellular changes, and currently, preclinical research (using animal models) and clinical trials have been conducted. Although animal model preclinical studies did show positive effects against AD pathology, almost all clinical trials with AD patients showed negative results.

Currently, the manifestation of AD is determined by measuring proteins in cerebral spinal fluids (CSF), such as the Aβ peptide 42, total tau or hyper phosphorylated tau protein levels [8,25]. However, these measurements involve invasive lumbar puncture for routine assessment of disease [26]. Neuroimaging techniques, such as positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, provide more conclusive evidence of AD pathogenesis [27]. These procedures are used to identify neurodegenerative disease markers, but to do so, they need to be executed late in disease progression –too late to initiate successful preventive or effective therapeutic measures [28]. A less invasive method to diagnose AD and other neurodegenerative diseases much earlier than current methods is needed, and one promising alternative is through the use of biomarkers. One such promising biomarker for AD is circulating miRNAs. The purpose of this article is to discuss latest developments in circulating miRNAs and their possible role in early, noninvasive identification and assessment of AD.

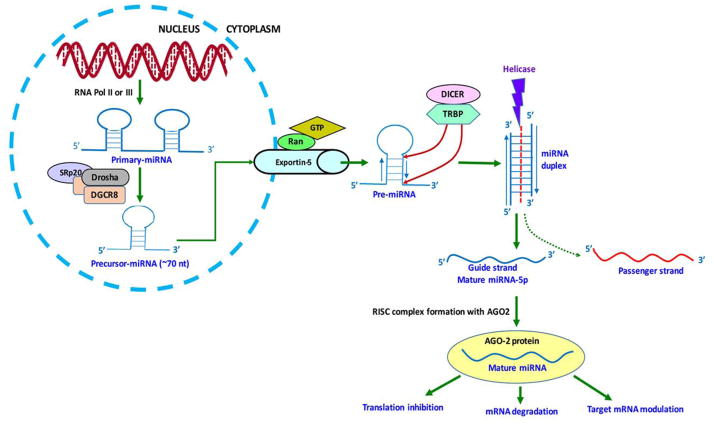

miRNA synthesis in cells

miRNA biogenesis pathways are similar in different organism species and cell types. Primary processing starts in the nucleus with the synthesis of multiple hairpin loop-like structures known as primary miRNA (Pri-miRNA) transcripts (Figure 1). Pri-miRNAs synthesized either from introns, protein coding genes that are specialized miRNA encoding genes, or from poly-cistronic transcripts by RNA polymerase II or III. Pri-miRNAs are further cleaved into shorter (~70 nt) hairpin loop-like structures that are precursor miRNA (Pre-miRNA) transcripts by the enzymatic action of microprocessor complex. These complexes contain one subunit of Drosha (a class II RNase III enzyme), two subunits of DiGeorge syndrome chromosomal region eight proteins, and one subunit of SRp20 (a splicing factor) [29]. Pre-miRNAs are transported to the cytoplasm via the exportin-5 pathway, which includes several other proteins, such as the ras-related nuclear and GTP proteins. Secondary processing of miRNAs occurs in the cytoplasm where the hairpin-loops of pre-miRNAs are further digested by Dicer, another RNase III enzyme, and by several other co-factors, such as Interferon-inducible, double-stranded RNA-dependent activator and HIV-1 TAR RNA-binding proteins, and mature miRNA duplexes of (21–25 nt) are generated [29]. miRNA duplex structures are separated by helicase and two single-stranded RNA molecules, termed guide strand and passenger strand, which were generated, based on their 5’ to 3’ complementarity. During this selection process, passenger strand is degraded, while the guide strand is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and functions as a mature miRNA [29–31]. If mature miRNA is produced from a 5’ strand, its nomenclature is miRNA-5p, and if it is generated from a 3’ strand, it is represented as miRNA-3p (http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org). Both of the 5p and 3p miRNAs function similarly and can form the RISC complex with Argonaute2 (Ago2) proteins. The miRNA-Ago2 complex targets the complementary seed sequence at the 3’UTR of mRNAs and leads to either translation inhibition or mRNA degradation [30].

Figure 1. miRNA synthesis pathway.

miRNA generation pathways include both nucleus and cytoplasmic steps. To generate miRNAs, primary-miRNAs are transcribed from miRNA encoding genes using RNA polymerase II or III. The pri-miRNAs were digested by microprocessor complexes to the hair pin-loop precursor-miRNA. Pre-miRNA is transported to the cytoplasm by the exportin five transporter and processed into a miRNA duplex structure using Dicer and TAR RNA-binding proteins (TRBP). miRNA duplex is separated by helicase into one guide strand, comprised of a mature miRNA-5p or a mature miRNA-3p miRNA and one passenger strand. A passenger strand is degraded while the guide strand forms an RISC complex with Ago2 proteins and targets the 3’UTR of mRNA. The resulting miRNAs modulates gene activity.

miRNAs synthesis occurs in the nucleus and cytoplasm and various nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins are involved in miRNA bioprocessing pathways. miRNA mediated gene modulation basically depends on the seed sequence complementarity with the target mRNA. Further research is needed to extensively understand the down-stream processing of miRNA maturation and regulation of cellular function.

Brain-enriched miRNAs and Synaptic Functions

From all of the known miRNA candidates almost 70% are expressed in the human brain, while very few miRNAs are considered brain-enriched miRNAs [32]. Some brain-enriched miRNAs are: miR-9, miR-7, miR-128, miR-125 a-b, miR-23, miR-132, miR-137, and miR-139 [33]. There is also a long list of miRNAs that are brain-specific or highly expressed in the brain, including: miR-134, miR-135, let-7g, miR-101, miR-181a-b, miR-191, miR-124, miR-let-7c, let-7a, miR-29a, and miR-107 [33–34]. MicroRNA expression in the mouse brain has been profiled through microarray and sequencing analysis of the frontal cortex and the hippocampus region. This analysis indicated that miR-let-7c is composed of 21 to 27% of all miRNA content in the mouse brain, while miR-128 is composed of eight to 20% of all miRNA content in the mouse brain. Other miRNAs – let-7b (8%), let-7a (9%), miR-29a (8%), miR-124 (8%), miR-709 (11%), and miR-26a –also comprise the majority of brain miRNAs [35].

Overall, vast majority of miRNAs expresses in brain and these brain-enriched miRNAs are the key regulators of different biological functions in neurons, such as synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and neuronal differentiation.

Secretion of miRNAs in circulatory biofluids

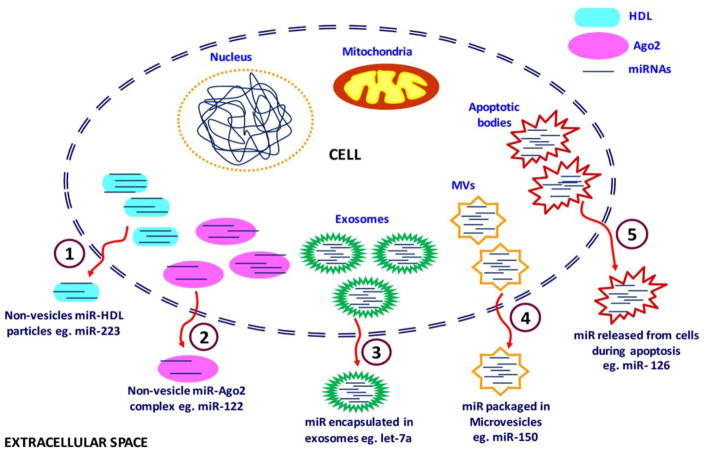

Accumulating evidence indicates that miRNAs are secreted in extracellular spaces in microvesicle-encapsulated form or are released in vesicle-free form; miRNAs are then bound with proteins or other compounds [12,14,36] miRNAs move into extracellular circulatory bio-fluids in one of five different modes (Figure 2). 1) miRNAs are bound to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles in a non-vesicle form, 2) they form an interesting complex with Ago2 proteins, 3) they are placed in exosomes, 4) they are encapsulated in micro-vesicles (MVs), and 5) miRNAs accumulate in apoptotic bodies. The main function of exosomes and MVs is to facilitate intra-cellular communication and transportation of various bioactive molecules (e.g., DNA, RNA, miRNA, and proteins). Arroyo et al. found that the majority of circulating miRNAs (90%) are found in MVs where they bind with Ago2 proteins [37]. miRNAs that associate with Ago2 proteins become resistant to the nuclease-rich environment, due to the high stability of the Ago protein in biofluids [36]. Some instances, cells have exhibited miRNA transport mechanisms for particular miRNAs, such as miR-122. miR-122 is found in liver-enriched cellular environments and has been exclusively detected in Ago2 protein complexes [37].

Figure 2. Secretion of miRNAS from a cell to extracellular spaces and circulatory biofluids.

Stem-loop pre-miRNA and mature miRNAs are secreted from the either in micro particle free form bound with proteins or in encapsulated macrovesicles. There are five main modes by which miRNAs are secreted into extracellular spaces and circulatory biofluids: (1) Non-vesicle bound with high density lipoproteins, (2) Non-vesicle bound with Ago2 proteins, (3) Encapsulated within exosomes, (4) packaged in macrovesicles and (5) Secretion within apoptotic bodies.

HDL particles of the size 8–12 nm mainly constitute phosphatidylcholine and apolipoprotein A-I, both of which form a stable ternary structure comprised of extracellular plasma miRNAs through divalent cation bridging [12]. HDL particles transport only a minor fraction of endogenous miRNAs in circulating biofluids. One such miRNA is miR-223, which, in atherosclerosis, is known to circulate in plasma comprised of HDL [38].

Exosomes are cell-derived vesicles that are found in many and possibly all biological fluids, including blood, urine, and media of the cultured cells [39]. Exosomes are particles approximately 50–100 nm in diameter. They are natural biological nano-vesicles or multivasicular bodies that originate from endosomes and are secreted from cells through their fusion with plasma membrane [12]. Studies of miRNAs have focused on exosomes as diagnostic molecules for several reasons: 1) exosomes in pathogenic states mainly contain disease-specific or deregulated miRNAs; studies have been undertaken to remove non-exosomal miRNAs in healthy cells, 2) exosomes have the potential to cross the blood barrier through transcytosis; hence, they can easily pass through endothelial cellular layers and circulate in biofluids, which is important in neurodegenerative or brain-related disorders, and 3) in circulatory systems of persons with neurodegenerative or brain-related disorders, miRNAs are present in their protective cellular RNase form [40]. miRNAs released from exosomes from persons with such disorders may be the remnants of dead cells. Cheng et al. demonstrated that exosomes in biofluids, rather than cell-free blood offer a protective and enriched source of miRNAs, which can be used for biomarker studies [40]. MVs are slightly larger vesicles (100–4000 μm) that are generated from cells via outward budding and blebbing of the plasma membrane. MVs are secreted by different cell types, such as neurons, muscle cells, inflammatory cells, and tumor cells [41]. However, platelets are the major source of MV secretion [41]. A well-studied miRNA is miR-150, which is from MVs and monocytes [42]. Among all MVs, apoptotic bodies are the largest that seep from the cell during apoptosis, and they carry miR-126 during this transportation [43–44]. miRNAs found in extracellular circulation are from macrovesicles and are resistant to cellular RNase [45]. During miRNA transport, the Ago2 protein forms part of the miRNA protein complex found in the cytoplasm of persons with neurodegenerative diseases, including AD and provides more stability to miRNAs, which helps miRNAs bind to target sites.

Although, so much research has been done to understand the mode of miRNA secretion, cell-cell transmission and circulation into biofluids, however precise mechanisms of miRNA origin and their localization are not completely understood. Further research still needed using biofluids, tissues and organs to unveil the link between miRNA origin and their secretion.

miRNAs detection in various biofluids

Besides the secretion of miRNAs in peripheral circulatory systems like blood and blood components (serum and plasma), interestingly miRNAs also been detected in common biofluids like: breast milk, saliva, bile, urine, stools, tears and colostrum [46–47]. Zhou et al, identified the four significant immune related miRNAs (miR-148a-3p, miR-30b-5p, miR-182-5p and miR-200a-3p) are abundantly expressed in the breast milk exosomes [48]. In the saliva of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) patients, miR-125a and miR-200a were found to be significantly down regulated and miR-27b is upregulated compared to control subjects [49–50]. ROC curve analyses revealed that miR-27b could be a valuable biomarker for distinguishing OSCC patients from control groups [50].

Biliary miRNAs are also could be important indicator for certain malignancies; like expression of miR-9 and miR-145 was noted to be signi cantly elevated in cholangiocellular cancer and might serve as potential biomarkers for biliary malignancies [51]. While, urinary miRNAs could be most logical candidate for detection of certain kidney disease, urinary tract infections, prostate and bladder cancers [52–53]. In recent report, urinary miRNA (miR-21) is significantly downregulated in prostate cancer (PCa) patients compared to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) patients [54]. As well, fecal miRNAs are also investigated as noninvasive potential biomarkers in colorectal cancer (CRC) and pancreatic cancer patients [55–56].

miR-21 and miR-106 level was found to be higher in the stool samples of CRC and adenoma patients compared to healthy individuals [55]. miRNAs were also detected in certain other tissues and organ specific human biofluids like: amniotic fluid, bronchial lavage, cerebrospinal fluids, peritoneal fluids, pleural fluid and seminal fluid. Detection of miRNAs in these tissue specific fluids could be used to access the body’s physiopathological status [46].

Circulatory miRNAs in common cancers

Studies to develop biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases can draw on methodologies and technologies being successfully developed to identify biomarkers– especially biofluid biomarkers – for cancer. Cancer is the leading cause of fatality, with 8.2 million people dying each year from a form of cancer (http://www.who.int/cancer/en/) [57]. The most common cancers in men are lung, prostate, colorectal, stomach, and liver cancers, while in women, the most common are breast, colorectal, lung, uterine, cervix, and stomach cancers (http://www.who.int/cancer/en/). The most commonly used biofluid biomarkers for cancer detection are specific proteins circulating in human blood, such as the alpha fetoprotein for liver cancer; chromogranin A for neuroendocrine tumors, especially carcinoid tumors; nuclear matrix protein 22 for bladder cancer; and carbohydrate antigen 125 for ovarian cancer [58]. Most of these blood proteins among others, are usually detected by various calorimetric and fluorescence immunoassays [59]. More accurate techniques for cancer detection are biopsy, endoscopy and radio-imaging tests such as PET-CT (positron emission computed tomography-computer tomography) and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) [59]. Unfortunately, above mention diagnostic methods are not sufficient for cancer detection at early stages, also some of them quite expensive [59]. Hence a more accurate, non-invasive early detection approach is needed for disease like cancer. miRNAs, are usually detected by such methods and technologies microarrays, RNA sequencing, Taqman probes and real-time qRT-PCR. However, these methods and technologies are capable of detecting miRNAs in diseased state at high levels, which usually corresponds to the detection of cancers at advanced stages of disease progression.

The molecular interaction between miRNAs and their mRNAs, which can be targeted, is well understood. However, the expression of miRNAs in all known human malignancies needs further investigation [60]. Further, methods and technologies to detect low levels of miRNAs and proteins in the biological sources, such as blood, saliva, plasma, and other bio-fluids, could led to the next-generation of biomarkers capable of detecting not only cancers but also other diseases, such as neurodegenerative diseases, at early stages of disease progression.

Studies exploring the role of circulatory miRNAs as biomarkers in various cancers are significantly increasing [5,57–58,60]. In studies of lung cancer, the disease that has been identified as being responsible for the highest rate of cancer-related mortality in men and the second leading cause of cancer related-death in women world-wide [57,61], three types of miRNAs were found to be deregulated in circulatory biofluids (e.g., serum and plasma, and in blood cells): miR-17-5p, miR-20a-5p and miR-21-5p [57]. Several other studies also found dysregulation of miR-21-5p and miR-24-3p in serum samples, and miR-21-5p, miR-210-3p, and miR-486-5p in plasma samples of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients [59,62]. Further, in plasma from these patients, the upregulation of miR-21-5p, miR-182-5p, and miR-210-3p, and the downregulation of miR-126-3p and 486-5p provided good diagnostic power at different stages of cancer progression [60,62]. In men with prostate cancer, the concentration of miR-21-5p, miR-141-3p, miR-100-5p, and miR-375 was higher in serum samples than in plasma samples, while the expression of miR-141-3p was higher in both serum and plasma samples [57]. In addition to their diagnostic value, the concentrations of plasma miRNAs – in particular, miR-20a-5b, miR-21-5b, and miR-145-5p – were useful in predicting recurrence of prostate cancer following localized treatment [63].

The concentrations of miRNA in serum samples from women with breast cancer were also vary between patients and healthy controls. In the serum samples from women with breast cancer, concentrations of the following miRNAs were downregulated: miR-133a, miR-139-5p, miR-143, miR-145 and miR-365 [64]. The concentrations of the following miRNAs from serum and plasma samples from women with breast cancer were upregulated: miR-24, miR-15a, miR-18a, miR-107, miR-425, miR-186, miR-425, miR-454, miR-140-3p, let-7b, miR-483-5p, miR-155, miR-126, miR-146b-5p, miR-320, miR-191 and miR-342-3p [64–66]. Further, the upregulation of miR-21-5p, miR-29a-3p, miR-195-5p, miR-373-3p, and let-7a-3p in serum from women with breast cancer correlated well with tumors at advanced stages of disease progression, high levels of vascular invasion, and high indices of cell proliferation [57,67–68].

In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients, liver-specific miR-122-5p showed consistent deregulation in serum and plasma samples [69–71]. Differential expression of miR-122-5p in serum distinguished HCC patients from healthy controls, with a sensitivity of 81.6% and a specificity of 83.3%. Moreover, a down-regulation of miR-122-5p in post-operative patients confirmed a positive correlation with HCC development [69,71].

In plasma from colorectal cancer patients, high levels of 221–3p can distinguished patients from controls, with a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 41% [72]. Further, the upregulation of 221-3p is correlated with expression of the tumor protein p53 in cancer tissues [72]. Several other studies confirmed that high levels of miR-15a, miR-103, miR-148a, miR-320a, miR-451, miR-596, miR-378, and miR-29a/c successfully predicted the recurrence of early-stage colorectal cancer [60,73–74].

Overall, miRNAs are well studied in cancer field, and these miRNAs are currently being considered to use as biomarkers in cancers but till now no miRNA candidate have approval for clinical use. Further research needed to confirm precise miRNA candidates as diagnostic biomarkers.

Circulatory miRNAs in neurodegenerative diseases

The most common neurodegenerative diseases include AD, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Parkinson’s disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Huntington’s disease (HD) [75]. Besides AD, very few studies have demonstrated the potential role of miRNAs as biomarkers that can be accessed relatively non-invasively through a blood draw. miRNA profiling in whole blood samples from PD patients showed a downregulation of miR-1, miR-22p, and miR-29a in the PD patients compared to controls, and differential expression of miRNAs as signatures for miR-16-2-3p, miR-26a-2-3p, and miR-30a differentiated patients who were treated for PD and patients who were not treated for PD [76]. Further, miRNA analysis of plasma samples indicated an upregulation of miR-181c, miR-331-5p, miR-193a-5p, miR-196b, miR-454, miR-125a-3p, and miR-137 in PD patients [77]. In a 2014 study, suppression of miR-19b, miR-29a, and miR-29c was found in the serum samples of PD patients [78].

A study of the SOD1-G93A mouse, an ALS mouse model, indicated the up-regulation of miR-206 in skeletal muscles and plasma through microarray analysis [79]. Serum samples from ALS patients, analyzed through microarray analysis, also showed an upregulation of miR-206 [79]. A recent study by Takahashi et al. used microarray analysis and validation by qRT-PCR to determine miRNAs in the plasma samples from two cohorts of ALS patients: (1) 16 ALS patients and 10 healthy controls; and (2) 48 ALS patients, 47 healthy controls, and 30 ALS controls [80]. The Takahashi study revealed an upregulation of miR-4649-5p and a downregulation of hsa-miR-4299 in ALS patients compared to healthy controls.

miRNAs are a promising biomarker to monitor AD pathogenesis particularly in its pre symptomatic state and initial phase. As shown in Table 1, very few studies using microarray and real-time qRT-PCR methods to assess miRNAs have been conducted on human bio-fluids samples, such as serum, plasma, CSF, and exosomes. Those studies that have used biofluids derived methods to assess circulatory miRNAs in on serum and plasma samples from patients with dementia due to MCI and AD dementia, and healthy controls.

Most of the reports we discussed here mentioned about normal/negative controls or healthy controls or non-demented controls. All controls were neurologically healthy, as confirmed by medical history, laboratory examinations, general examinations and Mini-Mental State examinations (MMSE). Subjects with some significant diseases like, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, hemorrhagic stroke, Ischemic stroke, cancer, glaucoma and infectious diseases were excluded from the study.

Overall, these studies suggest that circulatory miRNAs are potential biomarkers for ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases. Though, only limited reports are available in case of neurodegenerative disease therefore more research needs to be granted in this field. This article reviewed the details about the possibilities of circulatory miRNAs as biomarker in AD.

Circulatory miRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease

(i) Whole blood as sources of circulatory miRNAs

Whole blood is the most reliable specimen for the assessment of human disease, and blood draws are minimally invasive. A recent study evaluating whole blood samples re-analyzed a publically available small RNA-Seq data set for peripheral biomarker, derived from blood samples taken from AD patients (n = 48) and normal control subjects (n = 22) [81]. It also analyzed whole blood for miRNA expression, using single-end sequencing on Hiseq 2000 (Illumina). The main aim of the Satoh study was to establish a web-based miRNA data analysis pipelinethat combines results from studies of circulatory miRNAs in blood [81]. The Satoh study found differential expression of 27 miRNAs in AD (n=48) patients and normal control subjects (n=22). They found the expression of 13 miRNAs upregulated in the AD patients compared to the controls (Table-1): miR-26b-3p, miR-28–3p, miR-30c-5p, miR-30d-5p, miR-148b-5p, miR-151a-3p, miR-186–5p, miR-425–5p, miR-550a-5p, miR-1468, miR-4781–3p, miR-5001–3p, and miR-6513–3p. And they found the expression of 14 miRNAs downregulated: let-7a-5p, let-7e-5p, let-7f-5p, let-7g-5p, miR-15a-5p, miR-17–3p, miR-29b-3p, miR-98–5p, miR-144–5p, miR-148a-3p, miR-502–3p, miR-660–5p, miR-1294, and miR-3200–3p. ROC curve analysis revealed significant discrimination potential in all 27 miRNAs. However accuracy of best 10 miRNAs is mentioned in Table-2a. Further, the potential role of these miRNAs as a biomarker for neurodegenerative diseases needs to be determined after research analyzing miRNAs on large populations of patients with neurodegenerative diseases and control subjects.

(ii) Expression of miR-34a and miR-181b in blood mononuclear cells

An early study by Schipper et al., analyzed miRNAs in blood samples from AD patients (n = 16) and negative controls (n = 16), using expression profiling of RNA in blood mononuclear cells (BMCs) [82]. This study found an upregulation of miR-34a and miR-181b through microarray and real-time PCR analysis. This study did not establish miRNAs as a biomarker for AD because BMCs are not a good source of cell free miRNAs however, the Schipper et al. study is useful in establishing that miRNA expression is involved in BMCs from blood samples of AD and that miRNA may be a possible target for determining the presence of AD in patients.

(iii) Serum as a source of circulatory miRNAs for AD estimation

Serum is the most suitable circulatory biofluid for identifying miRNAs as potential biomarkers for AD and it is an appropriate source for cell free miRNAs. In fact, most studies of miRNAs as a biomarker for AD were conducted, using serum samples (Table 1). In one study, serum samples from seven AD patients were compared to serum samples from seven negative controls. QRT-PCR analysis revealed five miRNAs that were downregulated: miR-137, miR-181c, miR-9, miR-19a, and miR-29b [83]. This study also found miR-181b to be downregulated in the serum from AD patients but was upregulated in BMCs from the patients [82]. In another study, using miRNA PCR array analysis, Galimberti et al. investigated 84 of the most abundantly expressed miRNAs in serum samples from a cohort consisting of seven AD patients and six non-inflammatory neurological disease control subjects (NINDCs) [84]. They found four miRNAs to be significantly downregulated: miR-125b, miR-23a, and miR-26b. These results were compared to results of serum samples from a larger cohort of subjects: 15 patients with AD, 12 NINDCs, 8 inflammatory neurological disease controls (INDCs), and 10 patients with frontotemporal dementia (FTD). A significant downregulation of three miRNAs (miR-125b, miR-23a and miR-26b) was found only in the AD patients (table 1). Additional expression analysis of these three miRNAs in CSF from the AD and NINDC patients showed low levels of miR-125b and miR-26b in the AD patients, but not in the NINDC patients. Interestingly, miR-26b negatively correlated with tau and Ptau levels in the AD patients. ROC curve analysis showed a significant area under curve (AUC) value of 0.77 for miR-26b while the AUC value of miR-125b was 0.82 (Table-2b). These data suggest that miR-26b and miR-125b may be a diagnostic biomarker capable of distinguishing AD from NINDC subjects [84]. This study used small cohorts of subjects (NC: 18, AAD: 22, FTD:10 and INDCs: 8) (Table 1) for each subject group in Galimberti et al. [84]. The numbers of subjects need to increase substantially to determine whether the findings can be replicated in larger cohorts.

Table 1.

Summary of Circulatory micro RNA studies in Alzheimer’s disease

| Sources | Study groups | Sex ratio (Male vs Female) | miRNA detection methods | Up-regulated miRNAs | Down-regulated miRNAs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Blood | NC=22 | M=11, F=11 | Small RNA sequencing dataset | miR-26b-3p, miR-28–3p, miR-30c-5p, miR-30d-5p, miR-148b-5p, miR-151a-3p, miR-186–5p, miR-425–5p, miR-550a-5p, miR-1468, miR-4781–3p, miR-5001–3p, and miR-6513–3p | let-7a-5p, let-7e-5p, let-7f-5p, let-7g-5p, miR-15a-5p, miR-17–3p, miR-29b-3p, miR-98–5p, miR-144–5p, miR-148a-3p, miR-502–3p, miR-660–5p, miR-1294, and miR-3200–3p | Satoh et al., 2015 [81] |

| AD=48 | M=23, F=25 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| PBMC | NC=16 AD=16 |

NA | Microarray | miR-34a, miR-181b | - | Schipper et al., 2007 [82] |

|

| ||||||

| Serum | NC=7 | M=4, F=3 | QRT-PCR | - | miR-137, miR-181c, miR-9, miR-29a, miR-29b | Geekiyanage et al., 2012 [83] |

| MCI/EAD=7 | M=1, F=5 | |||||

| AD=7 | M=2, F=5 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Serum/CSF | NC=18 | M=13, F=5 | miRNA PCR array & TaqMan QRT PCR assay | - | miR-125b, miR-23a, miR-26b | Galimberti et al., 2014 [84] |

| AD=22 | M=8, F=14 | |||||

| FTD=10 | M=2, F=8 | |||||

| INDCs=8 | M=2, F=8 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Serum | NC=155 | M=75, F=80 | QRT-PCR | miR-9 | miR-125b, miR-181c | Tan et al., 2014 [85] |

| AD=105 | M=57, F=48 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Serum | Cohort 1 |

Discovery Sequencing |

miR-3158-3p, miR-27a-3p, miR-26b-3p, miR-151b | miR-36, miR-98-5p, miR-885-5p, miR-485-5p, miR-483-3p, miR-342-3p, miR-30e-5p, miR-191-5p, let-7g-5p, let-7d-5p | Tan et al., 2014 [86] | |

| NC= 50 | M=25, F=25 | |||||

| AD=50 | M=25, F=25 | |||||

| Cohort 2 |

Validation QRT-PCR |

|||||

| NC=155 | M=70, F=85 | |||||

| AD=158 | M=78, F=80 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Serum | Cohort 1 | NC M=65, F=58 AD M=72, F=55 |

Discovery Solexa Sequencing Validation RT-qPCR assay |

- | miR-31, miR-93, miR-143, miR-146a | Dong et al., 2015 [87] |

| NC=48 | ||||||

| AD=48 | ||||||

| Cohort 2 | ||||||

| NC=75 | ||||||

| AD=79 | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Serum exosomes | Cohort 1 |

Discovery Sequencing |

miR-361-5p, miR-30e-5p, miR-93-5p, miR-15a-5p, miR-143-3p, miR-335-5p, miR-106b-5p, miR-101-3p, miR-425-5p, miR-106a-5p, miR-18b-5p, miR-3065-5p, miR-20a-5p, miR-582-5p | miR-1306-5p, miR-342-3p, miR-15b-3p | Cheng L et al., 2014 [40] | |

| HC=23 | M=13, F=10 | |||||

| MCI=3 | M=2, F=1 | |||||

| AD=23 | M=9, F=13 | |||||

| Cohort 2 |

Validation QRT-PCR |

|||||

| HC=36 | M=14, F=21 | |||||

| MCI=8 | M=4, F=4 | |||||

| AD=16 | M=5, F=10 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Plasma | Cohort 1 |

Discovery nCounter miRNA assay (Nanostring) |

miR-323b-5p, miR-545-3p, miR-563, miR-600, miR-1274a, miR-1975 | let-7d-5p, let-7g-5p,miR-15b-5p, miR-142-3p, miR-191-5p, miR-301a-3p, miR-545-3p, | Kumar et al., 2013 [88] | |

| HC=20 | M=10, F=8 | |||||

| MCI=9 | M=3, F=6 | |||||

| AD=11 | M=6, F=5 | |||||

| Cohort 2 |

Validation TaqMan QRT-PCR |

|||||

| NC=17 | M=9, F=8 | |||||

| AD=20 | M=10, F=10 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Plasma exosomes | NC=35 | M=18, F=17 | Illumina deep Sequencing | miR-548at-5p, miR-138-5p, miR-5001-3p, miR-659-5p | miR-185-5p, miR-342-3p, miR-141-3p, miR-342-5p, miR-23b-3p, miR-338-3p, miR-3613-3p | Lugli et al., 2015 [89] |

| AD=35 | M=15, F=20 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| CSF, ECF | NC=6 AD=6 |

NA | Microarray | miR-9, miR-125b, miR-146a, miR-155 | - | Alexandrov et al., 2012 [90] |

|

| ||||||

| CSF | NC=28 | M=14, F=14 | Open Array QRT-PCR |

miR-146a, miR-100, miR-505, miR-4467, miR-766, miR-3622b-3p, miR-296 | miR-449, miR-1274a, miR-4674, miR-335, miR-375, miR-708, miR-219, miR-103 | Denk et al., 2015 [7] |

| AD=22 | M=9, F=13 | |||||

NC: Negative control; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; MCI: Mild cognitive impairment; FTD: Frontotemporal dementia; INDCs, inflammatory neurological disease controls; M: Male; F: Female; NA: not available.

In a study determining miRNAs in serum samples from AD patients and health control subjects, miR-125b was found be more downregulated in AD patients compared to serum samples from healthy controls [85]. Serum from the AD patients had more significant AUC value (0.85, p=<0.0001), indicating a higher diagnostic potential for miR-125b [85]. In this same study, qRT-PCR analysis revealed miR-181c to be down-regulated in AD patients, and miR-9, upregulated. The AUC value of miR-181c and miR-9 was found to be significant at 0.74 and 0.62, respectively, indicating the potential importance miR-181c and miR-9 as biomarkers for AD.

Using high-throughput sequencing, Tan et al. conducted a genome-wide expression profiling of miRNAs in sera from 50 patients with AD and from 50 negative controls [86]. Candidate miRNA molecules were identified and examined against miRbase database Release 19, which detected 90 different miRNAs that were significantly modulated in “probable” AD patients. miR-36 was identified as a novel miRNA, not previously identified on miRbase-19. Fourteen miRNAs were found differentially expressed (±2-fold) in the sera from the AD patients and the negative controls. Among the 14 miRNAs, 4 were upregulated in the sera from the AD patients but not in the negative controls: miR-3158-3p, miR-27a-3p, miR-26b-3p, and miR-151b; and 10 were downregulated: miR-36, miR-98-5p, miR-885-5p, miR-485-5p, miR-483-3p, miR-342-3p, miR-30e-5p, miR-191-5p, let-7g-5p, and let-7d-5p. Validation of the 14 miRNAs using qRT-PCR on serum samples from 158 AD subjects and 155 negative controls revealed a downregulation of only six miRNAs in sera from “probable” AD patients: miR-483-3p, miR-342-3p, miR-98-5p, miR-191-5p, miR-885-5p, and let-7d-5p (Table. 1). The remaining 8 miRNAs did not significantly vary in the AD patients and negative controls [86]. ROC curve analysis of these eight miRNAs indicated that miR-342-3p had the highest diagnostic accuracy with an AUC value of 0.84 and a cut-off value of 0.93 (Table 2b). Further studies aiming to characterize miRNAs in biofluids need to focus on much larger numbers of subjects than has been the case in previous research designs.

Table 2.

Diagnostic potential of circulatory miRNAs in AD vs NC

| (a) Whole blood samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNAs | Status | AUC | Sensitivity | References |

| miR-1468 | up | 0.884 | <0.0001 | Satoh et al., 2015 [81] |

| miR-4781-3p | up | 0.832 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-26b-3p | up | 0.809 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-28-3p | up | 0.789 | 0.0001 | |

| miR-151a-3p | up | 0.770 | 0.0003 | |

| miR-144-5p | Down | 0.799 | <0.0001 | |

| miR-148-3p | Down | 0.752 | 0.0007 | |

| Let-7g-5p | Down | 0.727 | 0.0024 | |

| miR-660-5p | Down | 0.720 | 0.0033 | |

| miR-15a-5p | Down | 0.715 | 0.0040 | |

| (b) Serum samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNAs | AUC | p-value | 95% Confidence Interval | References |

| miR-125 | 0.82 | 0.005 | 0.65–0.98 | Galimberti et al., 2014 [84] |

| miR-26b | 0.77 | 0.019 | 0.59–0.95 | |

| miR-9 | 0.62 | 0.004 | 0.53–0.71 | Tan et al., 2014 [85] |

| miR-125b | 0.85 | <0.0001 | 0.80–0.90 | |

| miR-181c | 0.74 | <0.0001 | 0.67–0.81 | |

| miR-985p | 0.66 | <0.0001 | 0.59–0.72 | Tan et al., 2014 [86] |

| miR-885-5p | 0.62 | 0.0003 | 0.56–0.68 | |

| miR-483-3p | 0.63 | 0.0001 | 0.57–0.69 | |

| miR-191-5p | 0.73 | <0.0001 | 0.67–0.79 | |

| Let-7d-5p | 0.67 | <0.0001 | 0.57–0.70 | |

| miR-342-3p | 0.84 | <0.0001 | 0.79–0.89 | |

| miR-31 | 0.72 | - | 0.64–0.80 | Dong et al., 2015[87] |

| miR-93 | 0.69 | - | 0.61–0.78 | |

| miR-143 | 0.70 | - | 0.62–0.79 | |

| miR-146a | 0.70 | - | 0.63–0.79 | |

| (c) Plasma samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNAs | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | References |

| miR-15b-5p | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.96 | Kumar et al., 2013 [88] |

| miR-142.3p | 0.96 | 0.65 | 1 | |

| miR-191-5p | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.76 | |

| Let-7g-5p | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.53 | |

| Let-7d-5p | 0.92 | 0.75 | 0.88 | |

| miR-545-3p | 0.74 | 0.2 | 0.88 | |

| miR-301a-3p | 0.67 | 0.25 | 1 | |

In studying the use of serum as a biofluid for the analysis of circulatory miRNAs, Dong et al., examined miRNA in the sera from AD patients, individuals with MCI and vascular dementia (VD), and non-demented controls [87]. Using Solexa sequencing and RT-qPCR analysis, Dong et al. identified four miRNAs that were down-regulated in the AD patients but not in any other subject group: miR-31, miR-93, miR-143, and miR-146a. The AUC values were significant and distinguished AD patients from controls in both sets of experimental approaches (Table 2b). However, these miRNAs levels did not distinguish MCI and VD patients from controls because only miR-93 and miR-146a were significantly elevated in MCI individuals compared to control subjects while, miR-143 was down-regulated, and miR-31 showed no change. In case of VD patients, miR-31, miR-93, and miR-146a were significantly up-regulated however miR-143 was downregulated [87]. Hence, difference in these miRNAs expression could be able to discriminate AD cases from control subjects, but not suitable to separate MCI and VD cases.

(iv) Serum exosomal miRNAs

Analysis of exosomal miRNAs from serum samples of AD patients, MCI individuals and healthy controls is thought to be a feasible approach to determining biomarkers for AD because the cargo in exosomes may offer an enriched population of miRNAs that is free from endogenous RNA contaminants e.g. ribosomal RNA [40]. Hence, exosomes may consider a house of disease-specific miRNA signature that provides the good diagnostic tools. In a study by Cheng et al., serum exosomes, miRNAs were processed for sequencing analysis in order to understand differentially expressed miRNAs in AD. Initial screening of a cohort comprised of serum exosomal miRNAs and findings from this study revealed a significant up-regulation of 14 miRNAs that may function as biomarkers: miR-361-5p, miR-30e-5p, miR-93-5p, miR-15a-5p, miR-143-3p, miR-335-5p, miR-106b-5p, miR-101-3p, miR-425-5p, miR-106a-5p, miR-18b-5p, miR-3065-5p, miR-20a-5p, and miR-582-5p; and a downregulation of three miRNAs: miR-1306-5p, miR-342-3p, and miR-15b-3p [40]. Those results were validated by qRT-PCR analysis; however, validation lacked ROC curve analysis of deregulated miRNAs for diagnostic accuracy and even MCI individual population is very less. Thus far, exosomal miRNA profiles may yield AD-specific miRNAs.

As discussed above, multiple serum/exosomes miRNAs have been identified and these miRNA may be useful in determining circulatory biomarkers for AD. Further, research is needed with large numbers of samples with different stages of disease progression.

(v) Plasma as a source of circulatory miRNAs

Another important sources of circulatory miRNAs is blood plasma, which makes up about 55 percent of the overall content of human blood. The main function of plasma is to assist in the transport of nutrients, hormones, and proteins to different parts of the body. Kumar et al. analyzed miRNAs in the plasma from AD and MCI patients and healthy control subjects [88]. Using nCounter miRNA assay (Nanostring Technology), they found six miRNAs (miR-323b-5p, miR-545-3p, miR-563, miR-600, miR-1274a, and miR-1975) upregulated in one cohort of AD patients, and seven miRNAs (let-7d-5p, let-7g-5p, miR-15b-5p, miR-142-3p, miR-191-5p, miR-301a-3p, and miR-545-3p) downregulated in AD and MCI patients compared to healthy controls (Table 1). Further, validation studies, using qRT-PCR, again confirmed the downregulation of these miRNA expressions in the AD patients compared to the healthy controls. However, studies using qRT-PCR analysis of miRNAs showed none of the miRNAs is upregulated [88]. ROC curve analysis revealed that miR-142-3p and miR-301a-3p exhibited the bestmiRNA signatures, with 100% specificity. But miR-142-3p has the higher sensitivity (0.65) than miR-301a-3p (0.25) (Table-2c). A combination of signatures from different miRNAs indicated a significant accuracy (miR-545-3p and miR-15b (AUC=0.96, sensitivity=0.9 and specificity=0.94). However, the AUC values of sensitivity and specificity that best characterized individual miRNAs was miR-191-5p, miR-15b-5p, and let-7d-5p, suggesting that these three miRNAs may have the greatest diagnostic accuracy [88]. Furthermore, to diagnose AD early in its pathogenesis an early next step would be needed to analyze the longitudinal plasma samples from a large cohort having the MCI.

(vi) Circulatory miRNAs in plasma exosomes

Like serum exosomes, plasma exosomes carry miRNAs associated with AD. A recent study by Lugli et al. used Illumina deep sequencing to determine differential expressions of miRNAs in plasma from patients with AD and healthy control subjects [89]. They found a total of 20 miRNAs downregulated; four miRNAs (miR-548at-5p, miR-138-5p, miR-5001-3p, and miR-659-5p) upregulated; and seven miRNAs (miR-185-5p, miR-342-3p, miR-141-3p, miR-342-5p, miR-23b-3p, miR-338-3p, and miR-3613-3p) significantly downregulated in AD patients compared to controls (Table-1). Among all of these miRNAs, miR-342-3p is arguably one of the most noteworthy because it is a brain-enriched miRNA, and its reduced expression was determined to be at a significant level (p=0.007), which was confirmed by a t-test [89].

(vii) Circulating miRNAs in cerebrospinal fluid and extracellular fluid

Cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) is a clear biofluid that is secreted by the choroid plexus and circulates into brain ventricles. CSF plays an important role in the inter-cerebral transportation of miRNAs (Cheng et al., 2014a) [40]. In studies that involve analysis of CSF, CSF is collected from the brain via lumber puncture [40]. In studies assessing CSF in neurological and neurodegenerative disorders, CSF has been found to be a source of circulating miRNAs. Microarray analyses in studies of CSF and extracellular fluid (ECF) samples from patients with AD and from healthy controls indicate a significant over-expression of miR-9, miR-125b, miR-146a, and miR-155 in the biofluids from AD patients (Table 1). However, these studies investigated miRNAs from only six patients with AD and six control subjects. Further, the diagnostic accuracy of this research has not been determined. Until biofluids from much larger groups of subjects are analyzed and until diagnostic accuracy is evaluated, miRNAs as possible biomarkers cannot be determined [90].

A recent study of CSF samples from a larger group of subjects (AD subjects [n=22] and healthy controls [n=28]) [7] was conducted. Four ml CSF was collected via lumbar puncture of subjects in a sitting position. The samples were processed for miRNA isolation. A total of 1178 miRNAs were profiled by Open Array qRT-PCR, according to miRbase version 14 (www.mirbase.org/). Analysis showed an upregulation of seven miRNAs in AD patients (miR-146a, miR-100, miR-505, miR-4467, miR-766, miR-3622b-3p, and miR-296) and a downregulation of eight miRNAs in AD patients (miR-449, miR-1274a, miR-4674, miR-335, miR-375, miR-708, miR-219, and miR-103) (Table 1). Diagnostic accuracy of these miRNAs was measured by ROC curve analysis. miR-146a, miR-375, miR-103, and miR-100 showed significant AUC values (0.97, 0.99, 0.87, and 0.72, respectively) [7]. In the Denk et al. study, the up- and down-regulation of particular miRNAs support miRNAs in CSF as potential biomarkers for distinguishing patients with AD from heterogeneous controls [7]. Studies of miRNA in biofluids such as CSF from much larger cohorts of subjects are needed in order to evaluate whether miRNAs might serve as biomarkers for distinguishing patients with AD from heterogeneous controls.

Critical analysis and discussion of circulatory miRNA studies

In this review, we discussed 12 studies in which 1268 participants were tested for the expression of circulating miRNAs in different biofluids from AD patients, persons with MCI, persons with VD, and healthy controls. A total of 100 miRNAs were identified and validated in different subject groups. Of the 100 miRNAs, 54 miRNA were upregulated and 46 were down-regulated in the AD patients and the persons with MCI. The researchers of most of these studies explained away the down-regulation of unique miRNA signatures even in similar type of cohort and same biological sources. Due to inconsistency in miRNA profiling data in different studies, it is as yet cannot be determined whether circulatory miRNAs in biofluids can function as biomarkers for neurological diseases, such as AD. Most of the studies used whole blood or a blood component (e.g., serum, plasma) as the primary sources of samples studied for circulatory miRNAs and non-blood source is CSF/ECF.

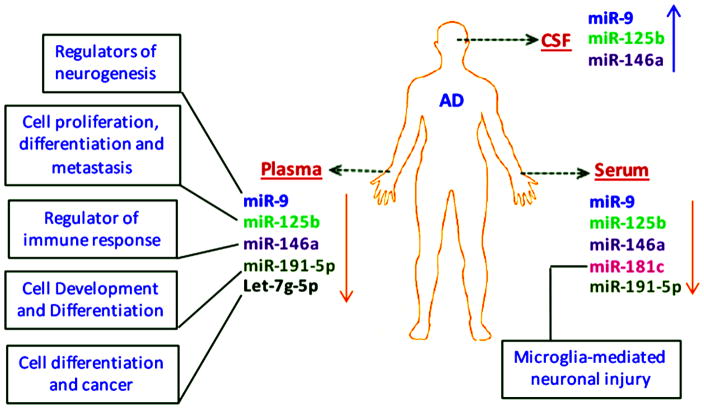

The studies discussed in this article found six miRNAs with similar signatures showed some uniformity miR-9, miR-125b, miR-146a, miR-181c, let-7g-5p, and miR-191-5p. miR-9 and miR-125b are brain-enriched miRNAs, and miR-181c, let-7g-5p, and miR-191-5p are abundantly expressed in the brain [33–34]. miR-9, miR-125b, and 146a were inversely expressed in CSF and serum/plasma samples from AD patients (Figure 3). Expression of miR-125b and 146a increased in the CSF and ECF serum samples from the AD patients while serum samples expression was downregulated [84–85,87,90]. Similarly, the up-regulation of miR-9 expression was common in CSF, ECF, and serum samples from AD patients. However, Geekiyanage et al. has reported a down regulation of miR-9 in all serum samples [83]. This inconsistent expression of miR-9 in different biofluids from different subject cohorts indicates the complexity of miRNA biogenesis, miRNA secretion, and variation in miRNA expression profiles. As yet, there is no unanimously identified miRNA that gives promise of being an effective biomarker for neurodegenerative diseases.

Figure 3.

Expression patterns of selected miRNAs in biofluids from AD patients. Serum, plasma and CSF are considered primary biofluids as sources for constant expression of circulatory miRNAs: miR-9, miR-125b, miR-146a, miR-181c, miR-191-5p and let-7 g-5p. Respective biological functions of these candidate miRNAs are also shown.

Few studies provided information about AUC values, sensitivity, and specificity. A low expression of let-7g-5p corresponded to significant AUC values in both blood and plasma samples from AD patients [81,88] (Table 2a). However, plasma samples of AD patients yielded the most accurate and specific ROC curve data for miR-15b-5p (AUC value, 0.96; sensitivity, 0.88; and specificity, 0.96) [88]. miR-191-5p, downregulated in plasma and serum samples from AD patients, showed a significant AUC value in the plasma (0.95) and serum (0.73) samples [86,88]. The AUC values of miR-125 (0.82), miR-9 (0.62), miR-146a (0.70) and miR-181c (0.74) suggest their diagnostic potential as biomarkers for AD patients. However, their down-regulation was restricted to serum samples [84–87]. In addition to their diagnostic accuracy, these miRNAs also perform important cellular functions in the brain. For example, miR-9 and miR-181c are involved in neurogenesis and microglial-mediated neuronal injuries (Figure 3) [91–92]. miR-146a is an important regulator of immunological and inflammatory responses in humans [93], and the major biological functions of miR-125b, miR-191-5p, and let-7g-5p are to regulate cell differentiation, proliferation, and metastasis [94–96].

The each report presented in Table 1 showed some unique miRNAs expression pattern in AD patients, however some studies showed overlapping in miRNA signatures. One reason for this kind of miRNA expression complexity may be due to epigenetic and environmental factors that are highly variable among different human populations [97]. Beside, genotypic and phenotypic variation form individual to individual, other extraneous effects like life style, age, gender, body mass index and status of AD related alleles (ApoE and BACE) may also influence miRNA expression [97–98]. Hence, AD patients with different genetic variants and gene expression variability may show some aberration in miRNAs expression profile.

Other reason for differential miRNAs expression form study-to-study may be different methodological approaches that was followed by the authors. Difference in miRNA extraction protocols also leads to some discrepancies in miRNAs expression level from study-to-study. Most of the reports discussed in this review are large scale miRNA profiling studies which resulting from the three principal techniques i.e. sequencing, microarray and qRT-PCR. Most of the sequencing data showed the differential expression of unique miRNAs in AD cases compared to controls while microarray and qRT-PCR considered some common miRNAs in two or more studies. Further, normalization of miRNA data is ever challenging task in different sources with different detection techniques. Till date, numerous strategies is proposed for normalization for miRNA profiling methods, however, currently none of them is generally accepted [99]. Hence, heterogeneity in miRNAs normalization strategies could introduce some degree of variation in miRNAs expression in different studies.

Besides the diagnostic potential of circulatory miRNAs in AD and other various other disease, they also characterized as important candidate molecules in forensic bioanalytical procedures due to their tiny size and much more stability and specificity [100–101]. Important body fluids in forensic settings are blood, saliva, semen, vaginal secretion and menstrual blood, where different miRNAs are expressed differently eg. miR-451 and miR-16 in blood, miR-658 and miR-205 in saliva, miR-135b and miR-10b in semen, miR-124a and miR-372 in vaginal secretion and miR-451 and miR-412 in menstrual blood [100]. Wang et al, also employed seven candidate miRNAs that could be used as forensically relevant body fluid markers like miR-486 and miR-16 for venous blood, miR-214 for menstrual blood, miR-888 and miR-891a for semen, miR-138-2 for saliva and miR-124a for vaginal secretions, however only three biofluid-specific miRNAs (miR-486, miR-888, and miR-214) showed the potential as new markers for body fluid identification [102].

Conclusions and Future Directions

In this review, most studies are restricted to particular class of miRNAs, however promising thing in commonly expressed miRNAs (miR-9, miR-125b, miR-191-5p, mir-181c and let-7g-5p) is their brain specific or brain enriched nature [33–34]. When we are looking for the biomarker for AD, it is thought that brain-specific or brain enriched miRNAs will be the best candidate for this perspective. Whenever, the deformities occur in the brain at molecular level, an abnormal expression of miRNAs is to be expected in associated body fluids such as blood, CSF/ECF, urine and saliva. Hence, a detail research is needed to focus on brain-specific miRNAs and their implications in AD pathogenesis. Furthermore, most of the current miRNA biomarker research studies focused on AD but ignoring presymptomatic AD cases. However, fewer reports are related to AD associated mixed pathologies like vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia, amnestic MCI/probable early AD and probable AD. As discussed in this review, expression of miRNAs also vary in mixed pathologies compared to control groups but it is not consistent with AD progression. Therefore, more detailed studies on miRNAs expression in AD and AD-type dementia are needed to understand miRNAs in different stages of disease progression. In the end, a more uniform methodological process is urgently needed to screen peripheral biofluids in order to identify and establish circulatory miRNAs as peripherals biomarkers.

The studies and their findings presented in this article focused on particular miRNAs thought to be potential biomarkers for AD. More comprehensive research is needed to determine whether circulatory mRNAs can function as biomarkers of AD.

Highlights.

Micro RNAs play a key role in cellular processes, including development, cell proliferation, replicative senescence and aging.

Circulatory micro RNAs are promising peripheral biomarkers for human diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s.

Circulatory micro RNAs can be found in bodily fluids, including blood products serum/ plasma, cerebrospinal fluids, extracellular fluids, saliva and urine.

Micro RNAs are strong indicators of disease progression and pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease.

Acknowledgments

Work presented in this article is supported by NIH grants AG042178, AG047812 and the Garrison Family Foundation.

Abbreviations

- miR or miRNA

microRNA

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- CSF

cerebral spinal fluid

- ECF

extracellular fluid

- AUC

area under curve

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- MV

microvesicle

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- BMC

blood mononuclear cell

- NINDCs

non-inflammatory neurological disease control

- INDC

inflammatory neurological disease control

- FTD

frontotemporal dementia

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- VD

vascular dementia

- OSCC

Oral squamous cell carcinoma

- PCa

Prostate cancer

- BPH

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- MMSE

Mini-mental state examination

- BMI

Body mass index

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Genomics, Biogenesis, Mechanism and Function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooten NN, Fitzpatrick M, Wood WH, De S, Ejiogu N, Zhang Y, Mattison JA, Becker KG, Zonderman AB, Evans MK. Age-related changes in microRNA levels in serum. Aging. 2013;5:725–740. doi: 10.18632/aging.100603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang H, Yang H, Zhang C, Jing Y, Wang C, Liu C, Zhang R, Wang J, Zhang J, Zen K, Zhang C, Li D. Investigation of microRNA expression in human serum during the aging process. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70:102–109. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Kowdley KV. MicroRNAs in common human diseases. Geno Proteo Bioinfo. 2012;10:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwarzenbach H, Nishida N, Calin GA, Pantel K. Clinical relevance of circulating cell-free microRNAs in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:145–156. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar S, Chawla YK, Ghosh S, Chakraborti A. Severity of hepatitis C virus (genotype-3) infection positively correlates with circulating microRNA-122 in patients sera. Dis Markers. 2014;2014:435476. doi: 10.1155/2014/435476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denk J, Boelmans K, Siegismund C, Lassner D, Arlt S, Jahn H. MicroRNA profiling of CSF reveals potential biomarkers to detect Alzheimer’s disease. PloS One. 2015;10:e0126423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Femminella GD, Ferrara N, Rengo G. The emerging role of microRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Physiol. 2015;6:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harries LW. MicroRNAs as mediator of the aging process. Gene. 2014;5:656–670. doi: 10.3390/genes5030656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawahara Y. Human diseases caused by germline and somatic abnormalities in microRNA and microRNA-related genes. Cong Anomal. 2014;54:12–21. doi: 10.1111/cga.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machida T, Tomofuji T, Ekuni D, Maruyama T, Yoneda T, Kawabata Y, Mizuno H, Miyai H, Kunitomo M, Morita M. MicroRNAs in salivary exosomes as potential biomarkers of aging. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:21294–21309. doi: 10.3390/ijms160921294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creemers EE, Tijsen AJ, Pinto YM. Circulating microRNAs novel biomarkers and extracellular communicators in cardiovascular disease? Circ Res. 2012;110:483–495. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grasso M, Piscopo P, Confaloni A, Denti MA. Circulating miRNAs as biomarkers for neurodegenerative disorders. Molecules. 2014;19:6891–6910. doi: 10.3390/molecules19056891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung HJ, Suh Y. Circulating miRNAs in aging and age related disease. J Genet Genom. 2014;41:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mao P, Manczak M, Calkins MJ, Truong Q, Reddy TP, Reddy AP, Shirendeb U, Lo H-H, Rabinovitch PS, Reddy PH. Mitochondria-targeted catalase reduces abnormal APP processing, amyloid b production and BACE1 in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: implications for neuroprotection and lifespan extension. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:2973–2990. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy PH. Is the mitochondrial outer membrane protein VDAC1 therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Alzheimer’s Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia

- 18.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s Disease: Genes, Proteins, and Therapy. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaFerla FM, Green KN, Oddo S. Intracellular amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neuro. 2007;8:449–509. doi: 10.1038/nrn2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swerdlow RH. Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Interven Aging. 2007;2:347–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy PH, Manczaka M, Maoa P, Calkinsa MJ, Reddy AP, Shirendeba U. Amyloid-β and mitochondria in aging and Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for synaptic damage and cognitive decline. J Alz Dis. 2010;20:S499–S512. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reddy PH. Abnormal tau, mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired axonal transport of mitochondria, and synaptic deprivation in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2011;1415:136–148. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandimalla R, Reddy PH. Multiple faces of dynamin-related protein 1 and its role in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Biochim Biophy Acta. 2016;1862:814–828. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kandimalla R, Vallamkondu J, Corgiat EB, Gill KD. Understanding aspects of aluminum exposure in Alzheimer’s disease development. Brain Pathol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/bpa.12333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kandimalla RJL, Prabhakar S, Wani WY, Kaushal A, Gupta N, Sharma DR, Grover VK, Bhardwaj N, Jain K, Gill KD. CSF p-Tau levels in the prediction of Alzheimer’s disease. Biology Open. 2013;2:1119–1124. doi: 10.1242/bio.20135447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu HZY, Ong KL, Seeher K, Armstrong NJ, Thalamuthu A, Brodaty H, Sachdev P, Mather K. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: A systemic review. J Alz Dis. 2016;49:755–766. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zafari S, Backes C, Meese E, Keller A. Circulating biomarkers panels in Alzheimer’s disease. Gerontology. 2015;61:497–503. doi: 10.1159/000375236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pana Y, Liue R, Terpstrab E, Wangb Y, Qiaob F, Wang J, Tong Y, Pana B. Dysregulation and diagnostic potential of microRNA in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alz Dis. 2016;49:1–12. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Connerty P, Ahadi A, Hutvagner G. RNA binding proteins in the miRNA pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:31. doi: 10.3390/ijms17010031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meijer HA, Smith EM, Bushell M. Regulation of miRNA strand selection: follow the leader? Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42:1135–1140. doi: 10.1042/BST20140142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu MY, Zhang W, Yang T. Diverse microRNAs with convergent functions regulate tumorigenesis. Oncol Letters. 2016;11:915–920. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.4020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nowak JS, Michlewski G. miRNAs in development and pathogenesis of the nervous system. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:815–820. doi: 10.1042/BST20130044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adlakha YK, Saini N. Brain microRNAs and insights into biological functions and therapeutic potential of brain enriched miRNA-128. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:33. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shao NY, Hu HY, Yan Z, Xu Y, Hu H, Menzel C, Li N, Chen W, Khaitovich P. Comprehensive survey of human brain microRNA by deep sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Juhila J, Sipila T, Icay K, Nicorici D, Ellonen P, Kallio A, Korpelainen E, Greco D, Hovatta I. MicroRNA expression profiling reveals miRNA families regulating specific biological pathways in mouse frontal cortex and hippocampus. PloS One. 2011;6:e21495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turchinovich A, Samatov TR, Tonevitsky AG, Burwinkel B. Circulating miRNAs: cell-cell- communication function? Front Genet. 2013;4:119. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arroyoa JD, Chevilleta JR, Kroha EM, Rufa IK, Pritchardb CC, Gibsonb DF, Mitchella PS, Bennetta CF, Pogosova-Agadjanyand EL, Stirewaltd DL, Taitb JF, Tewaria M. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:365–373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019055108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vickers KC, Palmisano BT, Shoucri BM, Shamburek RD, Remaley AT. MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:423–433. doi: 10.1038/ncb2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keller S, Sanderson MP, Stoeck A, Altevogt P. Exosomes: From biogenesis and secretion to biological function. Immunol Letters. 2006;107:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng L, Doecke JD, Sharples RA, Villemagne VL, Fowler CJ, Rembach A, Martins RN, Rowe CC, Macaulay SL, Masters CL, Hill AF. Prognostic serum miRNA biomarker associated with Alzheimer’s disease shows concordance with neuropsychological and neuroimaging assessment. Mol Psy. 2014:1–9. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boon RA, Vickers KC. Intercellular Transport of MicroRNAs. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:186–192. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Liu D, Chen X, Li J, Li L, Bian Z, Sun F, Lu J, Yin Y, Cai X, Sun Q, Wang K, Ba Y, Wang Q, Wang D, Yang J, Liu P, Xu T, Yan Q, Zhang J, Zen K, Zhang CY. Secreted monocytic miR-150 enhances targeted endothelial cell migration. Mol Cell. 2010;39:133–44. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zernecke A, Bidzhekov K, Noels H, Shagdarsuren E, Gan L, Denecke B, Hristov M, Köppel T, Jahantigh MN, Lutgens E, Wang S, Olson EN, Schober A, Weber C. Delivery of microRNA-126 by apoptotic bodies induces CXCL12-dependent vascular protection. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra81. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Yoshioka Y, Takeshita F, Matsuki Y, Ochiya T. Secretory mechanisms and intercellular transfer of microRNAs in living cells. J Bio Chem. 2010;285:17442–17452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.107821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith-Vikos T, Slack FJ. MicroRNAs circulate around Alzheimer disease. Genome Biology. 2013;14:125. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-7-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weber JA, Baxter DH, Zhang S, Huang DY, Huang KH, Lee MJ, Galas DJ, Wang K. The MicroRNA Spectrum in 12 Body Fluids. Clinical Chemistry. 2010;56:1733–1741. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.147405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Igaz I, Igaz P. Diagnostic relevance of microRNAs in other body fluids including urine, feces, and saliva. EXS. 2015;106:245–52. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-0955-9_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou Q, Li M, Wang X, Li Q, Wang T, Zhu Q, Zhou X, Wang X, Gao X, Li X. Immune- related microRNAs are abundant in breast milk exosomes. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:118–123. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.8.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park NJ, Zhou H, Elashoff D, Henson BS, Kastratovic DA, Abemayor E, Wong DT. Salivary microRNA: Discovery, characterization, and clinical utility for oral cancer detection. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5473–5477. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Momen-Heravi F, Trachtenberg AJ, Kuo WP, Cheng YS. Genome wide study of salivary microRNAs for detection of oral cancer. JDR Clinical Research Supplement. 2014;93 doi: 10.1177/0022034514531018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shigehara K, Yokomuro S, Ishibashi O, Mizuguchi Y, Arima Y, Kawahigashi Y, Kanda T, Akagi I, Tajiri T, Yoshida H, Takizawa T, Uchida E. Real-time PCR-based analysis of the human bile microRNAome identi es miR-9 as a potential diagnostic biomarker for biliary tract cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Srivastava A, Goldberger H, Dimtchev A, Ramalinga M, Chijioke J, Marian C, Oermann EK, Uhm S, Kim JS, Chen LN, Li X, Berry DL, Kallakury BVS, Chauhan SC, Collins SP, Suy S, Kumar D. MicroRNA pro ling in prostate cancer-the diagnostic potential of urinary miR-205 and miR-214. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Papadopoulos T, Belliere J, Bascands JL, Neau E, Klein J, Schanstra JP. miRNAs in urine: a mirror image of kidney disease? Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15:361–374. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2015.1009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stuopelyt K, Daniūnaitė K, Jankevičius F, Jarmalaitė S. Detection of miRNAs in urine of prostate cancer patients. Medicina. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.medici.2016.02.007. Article in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Link A, Balaguer F, Shen Y, Nagasaka T, Lozano JJ, Boland CR, Goel A. Fecal MicroRNAs as novel biomarkers for colon cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1766–1774. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Link A, Becker V, Goel A, Wex T, Malfertheiner P. Feasibility of fecal microRNAs as novel biomarkers for pancreatic cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He Y, Lin J, Kong D, Huang M, Xu C, Kim TK, Etheridge A, Luo Y, Ding Y, Wang K. Current state of circulating microRNAs as cancer biomarkers. Clin Chem. 2015;61:1138–1155. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.241190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ma R, Jiang T, Kang X. Circulating microRNAs in cancer: origin, function and application. J Exp Clin Can Res. 2012;31:38. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-31-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yin Y, Cao Y, Xu Y, Li G. Colorimetric Immunoassay for Detection of Tumor Markers. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:5077–5094. doi: 10.3390/ijms11125077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khoury S, Tran N. Circulating microRNAs: potential biomarkers for common malignancies. Biomarker in Medicine. 2015;9:131–151. doi: 10.2217/bmm.14.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.American Cancer Society. Global Cancer Facts & Figures. 3. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shen J, Liu J, Liu Z, Todd NW, Zhang H, Liao J, Yu L, Guarnera MA, Li R, Cai L, Zhan M, Jiang F. Diagnosis of lung cancer in individuals with solitary pulmonary nodules by plasma microRNA biomarkers. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:374. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shen J, Hruby GW, McKiernan JM, Gurvich I, Lipsky MJ, Benson MC, Santella RM. Dysregulation of circulating microRNAs and prediction of aggressive prostate cancer. Prostate. 2012;72:1469–1477. doi: 10.1002/pros.22499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kodahla AR, Lyngc MB, Binderd H, Colda S, Gravgaardc K, Knoope AS, Ditze HJ. Novel circulating microRNA signature as a potential non-invasive multi-marker test in ER-positive early-stage breast cancer: A case control study. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:874–883. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sochor M, Basova P, Pesta M, Dusilkova N, Bartos J, Burda P, Pospisil V, Stopka T. Oncogenic MicroRNAs: miR-155, miR-19a, miR-181b, and miR-24 enable monitoring of early breast cancer in serum. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:448. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zearo S, Kim E, Zhu Y, Zhao JT, Sidhu SB, Robinson BG, Soon PSH. MicroRNA-484 is more highly expressed in serum of early breast cancer patients compared to healthy volunteers. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heneghan HM, Miller N, Kelly R, Newell J, Kerin MJ. Systemic miRNA-195 differentiates breast cancer from other malignancies and is a potential biomarker for detecting noninvasive and early stage disease. Oncologist. 2010;15:673–682. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jung EJ, Santarpia L, Kim J, Esteva FJ, Moretti E, Buzdar AU, Leo AD, Le XF, Bast RC, Park S-T, Pusztai L, Calin GA. Plasma microRNA 210 levels correlate with sensitivity to trastuzumab and tumor presence in breast cancer patients. Cancer. 2012;118:2603–2614. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li W, Xie L, He X, Li J, Tu K, Wei L, Wu J, Guo Y, Ma X, Zhang P, Pan Z, Hu X, Zhao Y, Xie H, Jiang G, Chen T, Wang J, Zheng S, Cheng J, Wan D, Yang S, Li Y, Gu J. Diagnostic and prognostic implications of microRNAs in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1616–1622. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Qi P, Cheng SQ, Wang H, Li N, Chen YF, Gao CF. Serum microRNAs as biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. PloS One. 2011;6:e28486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Giray BG, Emekdas G, Tezcan S, Ulger M, Serin MS, Sezgin O, Altintas E, Tiftik EN. Profiles of serum microRNAs; miR-125b-5p and miR-223-3p serve as novel biomarkers for HBV-positive hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41:4513–4519. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3322-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pu X-X, Huang G-L, Guo H-Q, Guo C-C, Li H, Ye S, Ling S, Jiang L, Tian Y, Lin T-Y. Circulating miR-221 directly amplified from plasma is a potential diagnostic and prognostic marker of colorectal cancer and is correlated with p53 expression. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1674–1680. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shivapurkar N, Weiner LM, Marshall JL, Madhavan S, Mays AD, Juhl H, Wellstein A. Recurrence of early stage colon cancer predicted by expression pattern of circulating microRNAs. PloS One. 2014;9:e84686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zanutto S, Pizzamiglio S, Ghilotti M, Bertan C, Ravagnani F, Perrone F, Leo E, Pilotti S, Verderio P, Gariboldi M, Pierotti MA. Circulating miR-378 in plasma: a reliable, haemolysis-independent biomarker for colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1001–1007. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reddy PH. Mitochondrial medicine for aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Neuromolecular Med. 2008;10:291–315. doi: 10.1007/s12017-008-8044-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Margis R, Rieder CR. Identification of blood miRNAs associated to Parkinson’s disease. J Biotechnol. 2011;152:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cardo LF, Coto E, de Mena L, Ribacoba R, Moris G, Menéndez M, Alvarez V. Profile of microRNAs in the plasma of Parkinson’s disease patients and healthy controls. J Neurol. 2013;260:1420–1422. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6900-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Botta-Orfila T, Morató X, Compta Y, Lozano JJ, Falgàs N, Valldeoriola F, Pont-Sunyer C, Vilas D, Mengual L, Fernández M, Molinuevo JL, Antonell A, Martí MJ, Fernández-Santiago R, Ezquerra M. Identification of blood serum micro-RNAs associated with idiopathic and LRRK2 Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci Res. 2014;92:1071–1077. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Toivonen JM, Manzano R, Oliván S, Zaragoza P, García-Redondo A, Osta R. MicroRNA-206: A potential circulating biomarker candidate for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Plos One. 2014;92:e89065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Takahashi I, Hama Y, Matsushima M, Hirotani M, Kano T, Hohzen H, Yabe I, Utsumi J, Sasaki H. Identification of plasma microRNAs as a biomarker of sporadic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Mol Brain. 2015;8:67. doi: 10.1186/s13041-015-0161-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Satoh J, Kino Y, Niida S. MicroRNA-Seq data analysis pipeline to identify blood biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease from public data. Biomarker Insights. 2015;10:21–31. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S25132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]