Abstract

Background

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) have many comorbidities and excess risks of hospitalization and death. Whether the impact of comorbidities on outcomes is greater in AF than the general population is unknown.

Methods

1430 AF patients and community controls matched 1:1 on age and sex were obtained from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Andersen-Gill and Cox regression estimated associations of 19 comorbidities with hospitalization and death, respectively.

Results

AF cases had a higher prevalence of most comorbidities. Hypertension (25.4%), coronary artery disease (17.7%), and heart failure (13.3%) had the largest attributable risk of AF; these along with obesity and smoking explained 51.4% of AF. Over a mean follow-up of 6.3 years, AF patients experienced higher rates of hospitalization and death than population controls. However, the impact of comorbidities on hospitalization and death was generally not greater in AF patients compared to controls, with the exception of smoking. Ever smokers with AF experienced higher than expected risks of hospitalization and death, with observed vs. expected (assuming additivity of effects) hazard ratios compared to never smokers without AF of 1.78 (1.56–2.02) vs. 1.52 for hospitalization and 2.41 (2.02–2.87) vs. 1.84 for death.

Conclusions

Patients with AF have a higher prevalence of most comorbidities; however, the impact of comorbidities on hospitalization and death is generally similar in AF and controls. Smoking is a notable exception; ever smokers with AF experienced higher than expected risks of hospitalization and death. Thus, interventions targeting modifiable behaviors may benefit AF patients by reducing their risk of adverse outcomes.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, risk factors, hospitalization, death

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia affecting between 2.7–6.1 million Americans,1–3 and with the aging population, the prevalence of AF is projected to increase to 8–12 million by the year 2050.2–4 The risk factors for AF have been studied and several risk prediction tools have been developed to ascertain an individual’s risk of developing AF.5–9 Patients with AF have an excess risk of hospitalization and death than patients without AF.10–16 While risk factors for AF, including older age, heart failure, coronary artery disease, and diabetes, are predictors of hospitalization and death in AF patients,17, 18 it is not known if the combination of certain comorbidities with the presence of AF imparts a larger than expected risk of hospitalization and death. This information on what (if any) comorbidities are associated with a larger risk of hospitalization and death in AF compared to the general population is needed to guide the comprehensive management of patients with AF. Thus, we systematically characterized comorbidities in AF patients and the general population in a community in Southeast Minnesota. First, we compared the prevalence and duration of 19 comorbid conditions in patients with AF and in population controls. Second, we determined the associations of comorbidities with hospitalization and death, testing whether the impact of specific comorbidities on these outcomes is stronger in AF than in the general population.

Methods

Study Population

This study utilized the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP), a records-linkage system allowing virtually complete capture of health care in residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota.19–22 Olmsted County is relatively isolated from other urban centers and only a few providers, mainly Mayo Clinic and its 2 affiliated hospitals and Olmsted Medical Center and its branch offices and affiliated hospital, deliver most health care to local residents. Thus, the retrieval of nearly all health care related events through the linkage of information from these health care providers captures virtually the entire health care experience of the Olmsted County population. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center Institutional Review Boards.

Study Design

This study was carried out utilizing 2 designs. First, we conducted a matched case-control study, with patients with incident AF serving as the cases and patients free of AF selected from the general population serving as controls. Second, we conducted a cohort study by following AF patients and their matched controls to compare their outcomes.

Incident Atrial Fibrillation Cases and Controls

Incident AF or atrial flutter from 2000 to 2010 among adults aged ≥18 was identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes 427.31 and 427.32 from all providers in the REP and electrocardiograms (ECGs) from Mayo Clinic. As previously described, both inpatient and outpatient encounters were captured and all records were manually reviewed to validate the events.11 AF occurring within 30 days of cardiac surgery were excluded; however, when observed, a future episode of AF unrelated to cardiac surgery was considered incident AF. For this study, a random sample of 1430 of the 3344 patients with incident AF from 2000 to 2010 was selected. Community controls were matched 1:1 to cases on sex, age (within 5 years), and calendar year of diagnosis.

Ascertainment of Comorbidities

For each case and control pair, the case’s date of incident AF was used as the index date for the matched pair. Comorbidities were ascertained by electronically retrieving diagnostic codes from inpatient and outpatient encounters at all providers indexed in the REP. We selected comorbidities that were identified by the US Department of Health and Human Services (US-DHHS) for studying multimorbidity.23, 24 This list contains 20 comorbidities; however, we excluded autism (n=0), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV; n=1), and hepatitis (n=41) due to low prevalence and cardiac arrhythmias because all cases have AF. In addition, we added anxiety as a potentially important chronic condition that was excluded from the US-DHHS list, resulting in 17 chronic conditions. More details about the definition of the chronic conditions are provided in Supplemental Table I. Diagnostic codes were available from 1975; thus, to ensure a consistent look back period, we pulled all diagnostic codes within the 25 years prior to index. In an attempt to decrease the risk of false-positive diagnoses, we required 2 occurrences of a code (either the same or two different codes within the code set for a given disease) separated by more than 30 days to confirm the diagnosis. The first code date was used as the index date of the comorbidity and the duration was calculated using a maximum of 25 years of history.

In addition, body mass index (calculated as weight (in kg) divided by height (in meters) squared) and smoking status were manually abstracted from the medical records at index, resulting in a total of 19 comorbid conditions.

Ascertainment of All-Cause Mortality and Hospitalizations

Hospitalizations for any cause occurring in an Olmsted County hospital were obtained from the REP. All hospitalizations from index date through December 31, 2014 were obtained for the AF cases and controls. The principal discharge diagnosis from the hospitalization was used to categorize the reason for hospitalization as due to cardiovascular causes (ICD-9 codes 390–459) or non-cardiovascular causes. Deaths from any cause were obtained through December 31, 2014 from inpatient and outpatient medical records, death certificates from the state of Minnesota, and obituaries and notices of death in the local newspapers.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). For the case-control study, the prevalence of comorbidities in AF cases vs. controls was compared using chi-square tests. Median duration of the comorbidities prior to index was compared between AF cases and controls using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Conditional logistic regression was used to estimate associations of each comorbidity with AF, unadjusted and after adjustment for all other conditions. Using the multivariable-adjusted model, attributable risks for each comorbidity were calculated using the following formula: Attributable risk (AR) = pe [(OR−1) / OR], where pe = proportion of cases with the exposure and OR = multivariable-adjusted odds ratio. Attributable risks were not calculated for protective factors. Attributable risks were also calculated for reductions in prevalence of combinations of comorbidities assuming a 25% and 50% reduction as well as complete elimination of the comorbidities.

For the cohort study, the mean cumulative function for hospitalizations over follow-up for AF cases and population controls were plotted using a nonparametric estimator.25 The basis for this function is that each person can be represented by a stepwise curve of cumulative number of hospitalizations over follow-up time until death or last follow-up. The mean cumulative function is the pointwise average of all the individual cumulative hospitalization curves. The Kaplan-Meier (KM) method was used to visualize the cumulative incidence of death over follow-up for AF cases and controls by plotting the 1-KM curves. Andersen-Gill modeling, which allows for modeling of multiple outcome events, was used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) of hospitalizations for AF cases and population controls in unadjusted models and models adjusting for all other comorbid conditions modeled as time-dependent variables. Cox regression models were used to estimate the associations of each comorbid condition with death. If a control received an ICD-9 code for AF over follow-up (n=46), they were censored at that time. Interactions between each comorbidity and AF case/control status were tested to determine whether the observed joint effects of a comorbidity and AF were greater than expected. Additive interactions were assessed using the method described by Li and Chambless.26 Multiplicative interactions were assessed by including a comorbidity*AF case/control status interaction term in the model. Then, for each comorbidity, a 4-level variable was created representing the presence/absence of the comorbidity and the AF case/control status; HRs were calculated using controls without the comorbidity as the referent group. The expected HRs were calculated as HR10 + HR01 − 1 for the additive interaction and HR10 × HR01 for the multiplicative interaction, where HR10 represents the HR for those with the comorbidity and no AF compared to those with no comorbidity/no AF and HR01 represents the HR for those without the comorbidity and AF compared to those with no comorbidity/no AF. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals and found to be violated during the first year of follow-up. Therefore, the Andersen-Gill and Cox regression analyses were repeated among 1-year survivors.

Results

Risk Factors for AF: A Case-Control Study

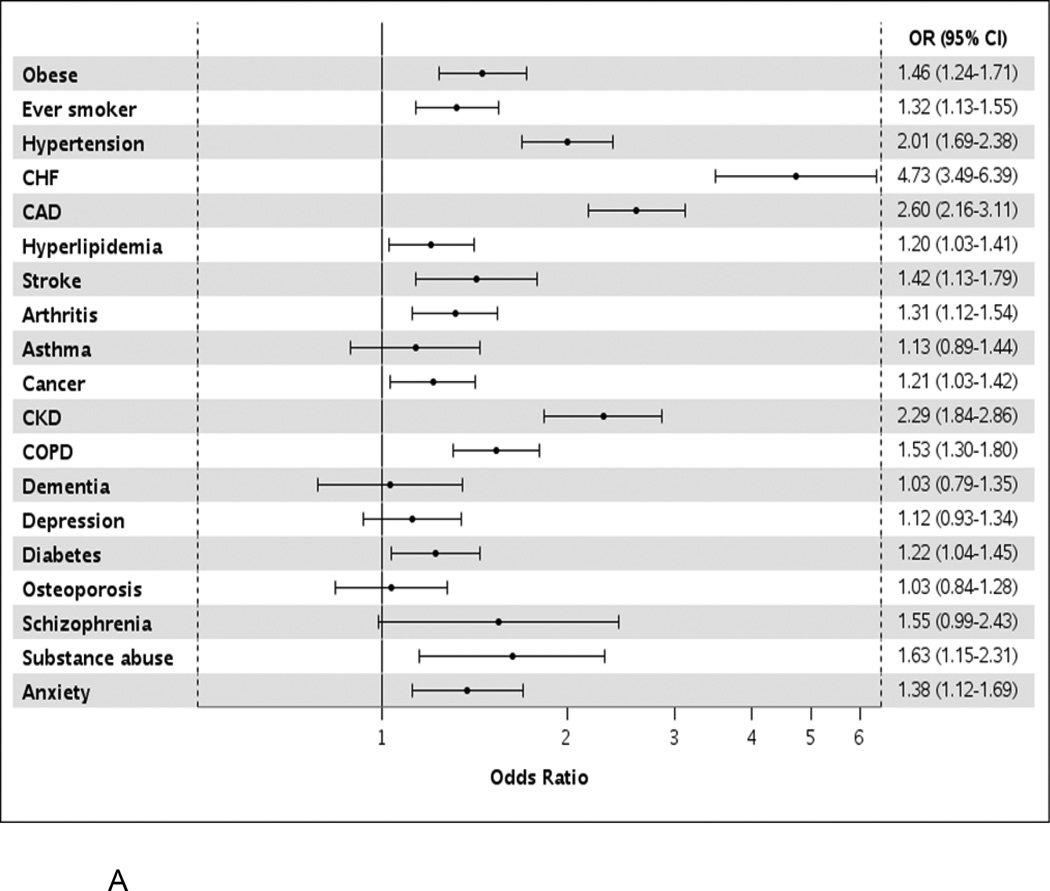

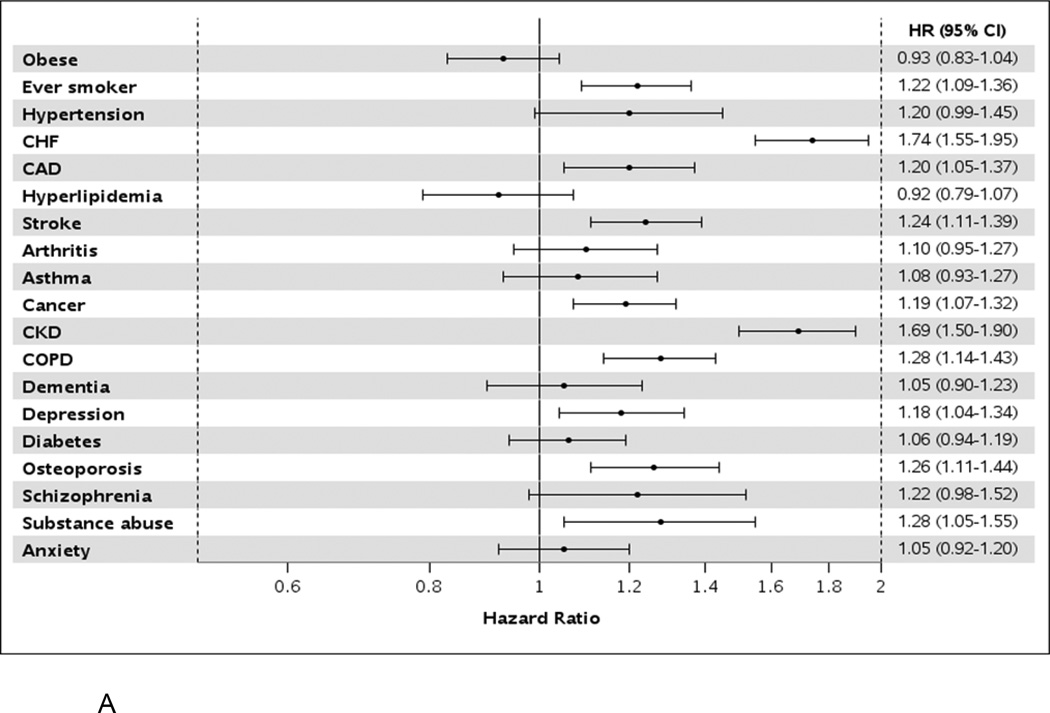

Among the 1430 matched pairs (48.6% men), the mean (SD) age was similar in AF cases and controls (73.6 (13.8) years and 72.7 (13.5) years, respectively). Hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and arthritis were the most common comorbidities in both cases and controls (Table I). Of the 17 chronic conditions (excluding obesity and smoking status), AF cases had an average of 5.6 comorbid conditions, whereas controls had 1 fewer condition with an average of 4.5 (p<0.001). The prevalence was higher in AF cases compared to controls for most of the comorbidities, with the exception of asthma, dementia, depression, osteoporosis, and schizophrenia, which were similar in cases and controls (Table I, Figure 1a). However, the median duration of conditions was similar in AF cases compared to controls for all conditions except hypertension, which was longer in AF cases (12.3 vs. 9.9 years for AF cases and controls, respectively; p=0.001; Supplemental Table II).

Table I.

Prevalence of Comorbidities in Atrial Fibrillation Cases Compared to Controls

| Cases (N=1430) |

Controls (N=1430) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity* | 525 (36.7) | 413 (28.9) | <0.001 |

| Ever smoking status | 748 (52.3) | 657 (45.9) | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1016 (71.1) | 818 (57.2) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 260 (18.2) | 70 (4.9) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 557 (39.0) | 300 (21.0) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 837 (58.5) | 780 (54.6) | 0.032 |

| Stroke | 208 (14.6) | 155 (10.8) | 0.003 |

| Arthritis | 770 (53.9) | 686 (48.0) | 0.002 |

| Asthma | 147 (10.3) | 131 (9.2) | 0.313 |

| Cancer | 557 (39.0) | 499 (34.9) | 0.025 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 289 (20.2) | 143 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 492 (34.4) | 364 (25.5) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 122 (8.5) | 119 (8.3) | 0.840 |

| Depression | 324 (22.7) | 298 (20.8) | 0.239 |

| Diabetes | 438 (30.6) | 382 (26.7) | 0.021 |

| Osteoporosis | 273 (19.1) | 267 (18.7) | 0.774 |

| Schizophrenia | 48 (3.4) | 31 (2.2) | 0.052 |

| Substance abuse disorder | 91 (6.4) | 59 (4.1) | 0.007 |

| Anxiety | 259 (18.1) | 201 (14.1) | 0.003 |

| Number of comorbidities, mean (SD) | 5.6 (2.9) | 4.5 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Number of comorbidities, median (IQR) | 5 (4–7) | 4 (2–6) | <0.001 |

| Number of comorbidities, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 35 (2.4) | 76 (5.3) | |

| 1 | 71 (5.0) | 131 (9.2) | |

| 2 | 111 (7.8) | 161 (11.3) | |

| 3 | 136 (9.5) | 173 (12.1) | |

| 4 | 178 (12.4) | 206 (14.4) | |

| 5 | 219 (15.3) | 199 (13.9) | |

| 6 | 163 (11.4) | 172 (12.0) | |

| 7 | 162 (11.3) | 126 (8.8) | |

| 8 | 120 (8.4) | 78 (5.5) | |

| 9 | 104 (7.3) | 65 (4.5) | |

| 10 | 56 (3.9) | 25 (1.7) | |

| 11 | 37 (2.6) | 10 (0.7) | |

| ≥12 | 38 (2.7) | 8 (0.6) |

Values are presented as n (%).

Obesity is defined as a body mass index ≥30 at index (using the case’s date of incident AF as the index date for the matched pair).

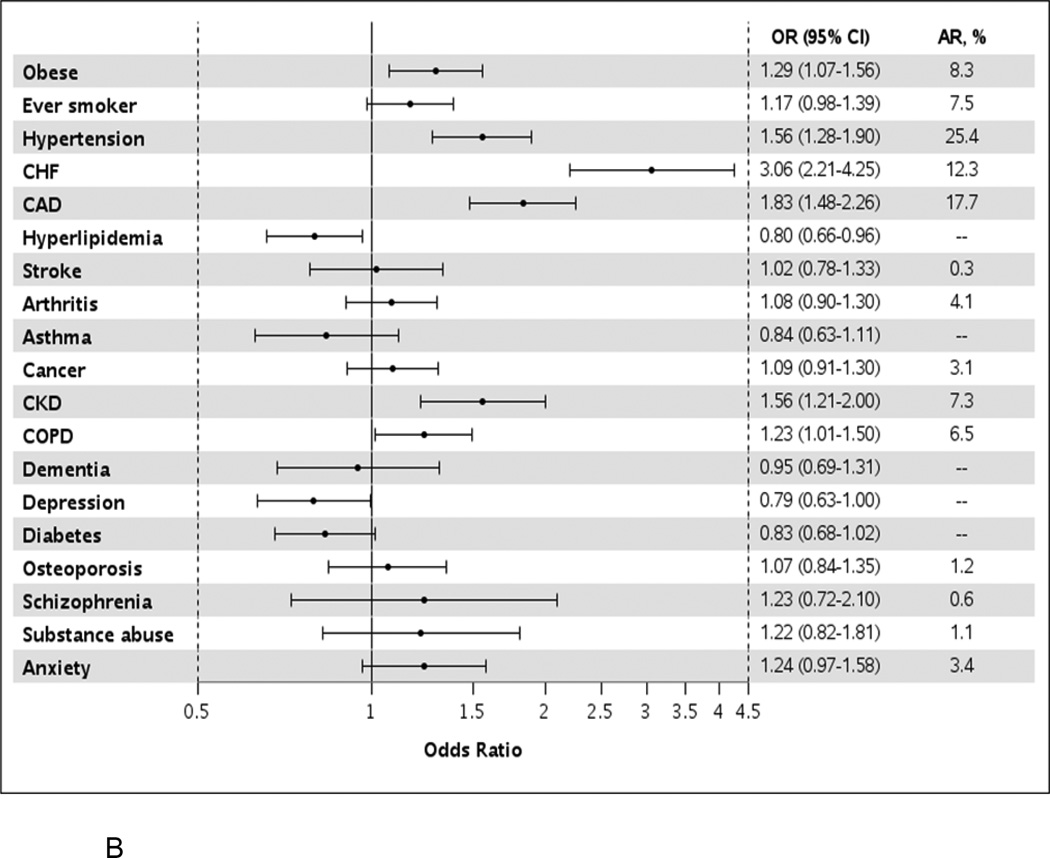

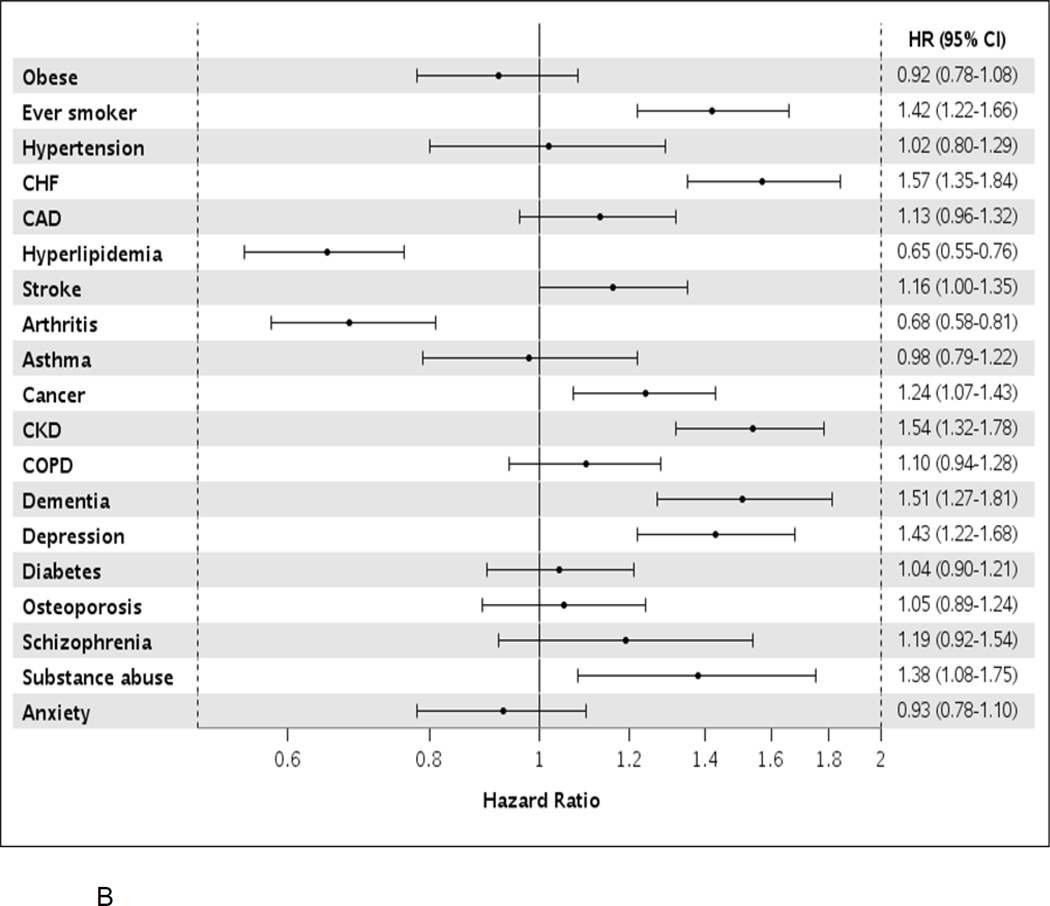

Figure 1.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for atrial fibrillation by presence of individual comorbidities in unadjusted models (Panel A) and after adjustment for all other comorbidities (Panel B).

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; AR, attributable risk; CHF, congestive heart failure; CAD, coronary heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

After adjusting for all other comorbidities, obesity, hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease remained significantly more common in AF (Figure 1b). More than a 3-fold increased odds of developing AF was observed for heart failure (OR, 3.1, 95% CI 2.2–4.3) and a nearly 2-fold increase odds of developing AF was observed for coronary artery disease (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.5–2.3). The comorbidities with the largest attributable risk of AF were hypertension (25.4%), coronary artery disease (17.7%), and heart failure (13.3%; Table II). For example, assuming a causal relationship, if hypertension was eliminated, 25% of AF would be avoided. If hypertension along with the modifiable health behaviors, obesity and smoking, were all eliminated, 37% of AF would be avoided. Eliminating the 5 risk factors for AF with the largest attributable risks (hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, obesity and smoking) would eliminate 51% of AF. However, complete elimination of all risk factors is an aspirational goal. More realistic estimates were thus generated (Table II). If a 25% reduction in the prevalence of hypertension, obesity, and smoking were obtained, a 10% reduction in AF would be expected. A 25% reduction in the top 5 risk factors would yield a 17% reduction in AF.

Table II.

Attributable Risks of Atrial Fibrillation for Varying Percentage Reductions in Comorbidities

| Percent Reduction in Comorbidity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity | 100% | 50% | 25% |

| Individual Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 25.4 | 12.3 | 6.7 |

| Coronary artery disease | 17.7 | 9.1 | 4.4 |

| Heart failure | 12.3 | 5.7 | 3.1 |

| Obesity | 8.3 | 4.1 | 2.1 |

| Smoking | 7.5 | 3.8 | 1.9 |

| Combinations of Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension, obesity, smoking | 36.6 | 19.1 | 10.4 |

| Coronary artery disease, heart failure | 25.8 | 13.7 | 7.2 |

| Hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, obesity, smoking |

51.4 | 29.9 | 16.8 |

Outcomes in AF: A Cohort Study

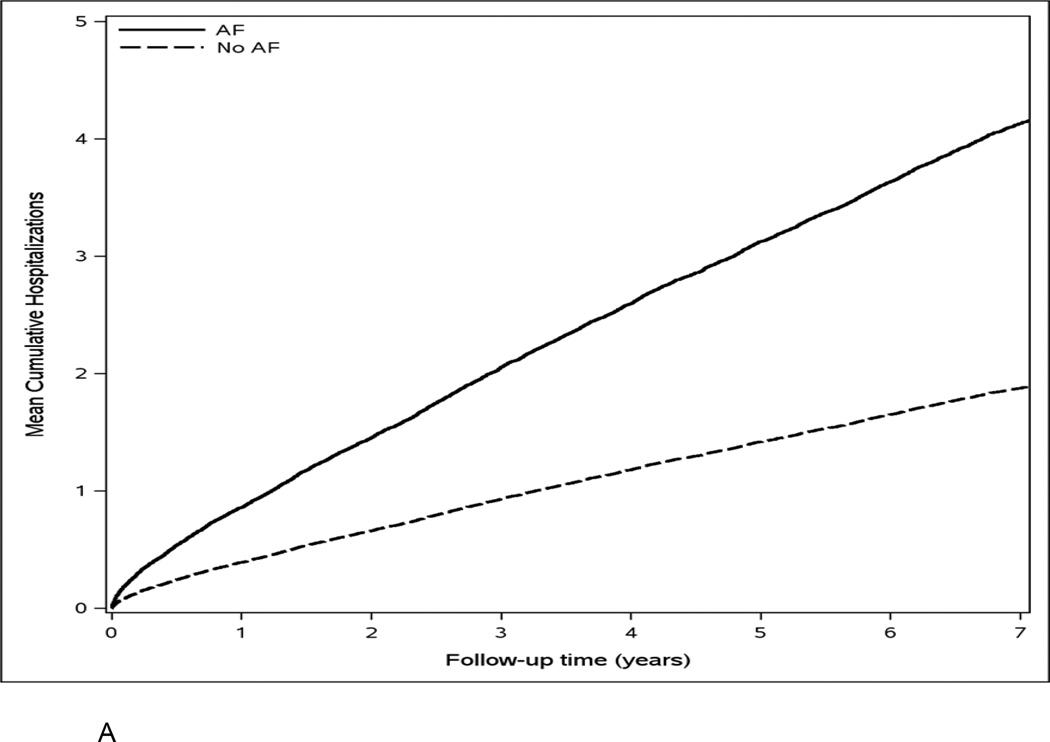

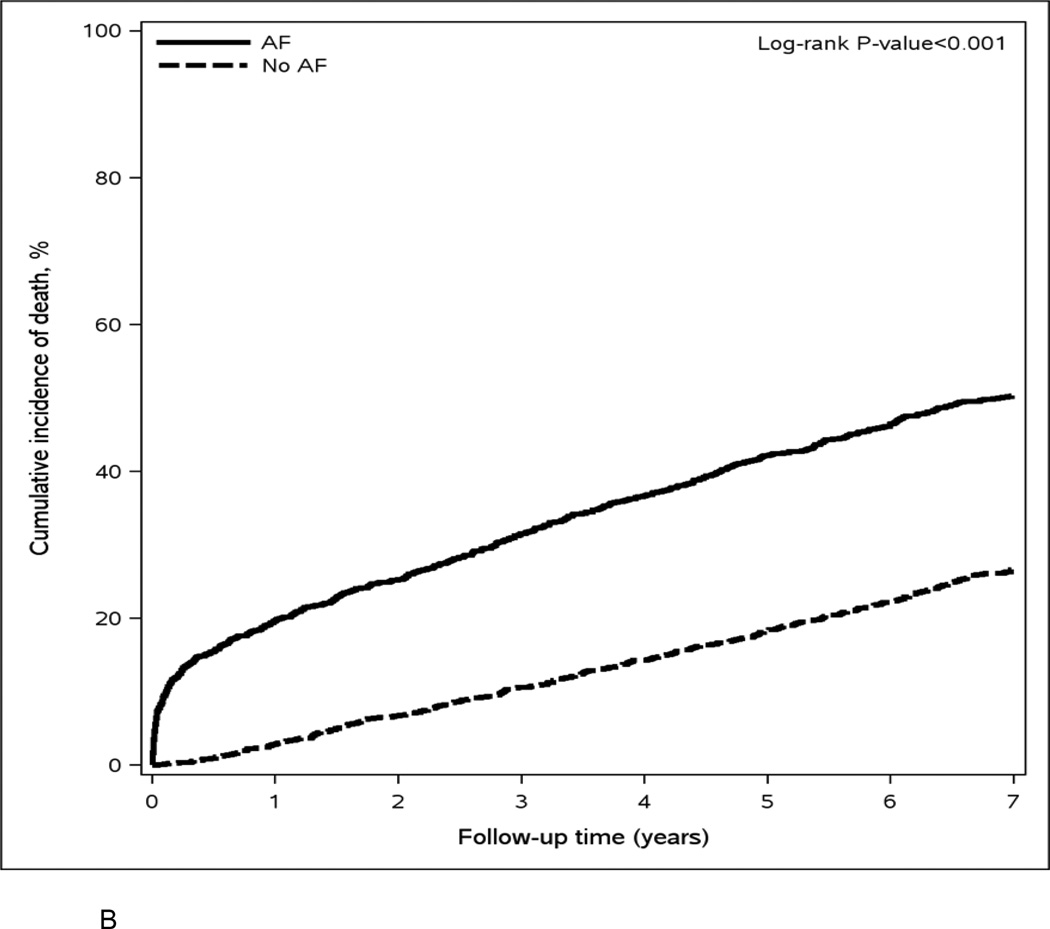

Over a mean (SD) follow-up of 6.3 (3.9) years, 7174 hospitalizations and 1292 deaths occurred; of these, 1557 hospitalizations and 322 deaths occurred within the first year. The rates of hospitalization were 58.8 and 26.4 per 100 person-years in AF cases and controls, respectively. The rates of all-cause death were 10.5 and 4.7 per 100 person-years in AF cases and controls. The cumulative number of hospitalizations and the cumulative incidence of death were higher in AF cases compared to population controls (Figure 2a and 2b). Patients with AF had a higher proportion of hospitalizations due to cardiovascular causes (36% vs. 20%) and cardiovascular deaths (42% vs. 31%) than those without AF.

Figure 2.

Mean cumulative number of hospitalizations (Panel A) and cumulative incidence of death (Panel B) for atrial fibrillation cases and population controls.

Among AF cases, after adjustment for age, sex, and all other comorbidities, patients with heart failure and chronic kidney disease experienced the highest risk of hospitalization (approximately 70% increased risk); ever smokers, those with diagnosed substance abuse, and those with coronary artery disease, stroke, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, and osteoporosis also had an increased risk of hospitalization (Figure 3a). Among 1-year survivors, all conditions listed above, as well as hypertension, were associated with an increased risk of hospitalization. When analyzing death as the outcome, ever smokers, those with substance abuse, and those with heart failure, cancer, chronic kidney disease, dementia, and depression were at an increased risk of death (Figure 3b). Among 1-year survivors, ever smokers and those with heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease, dementia, and depression were at an increased risk of death.

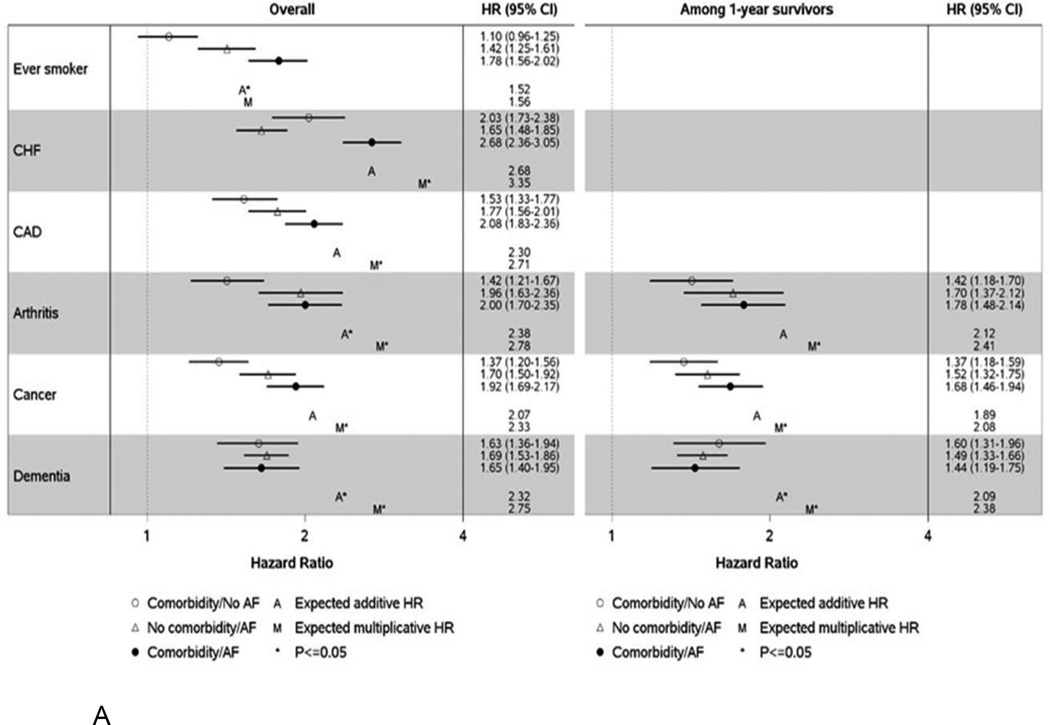

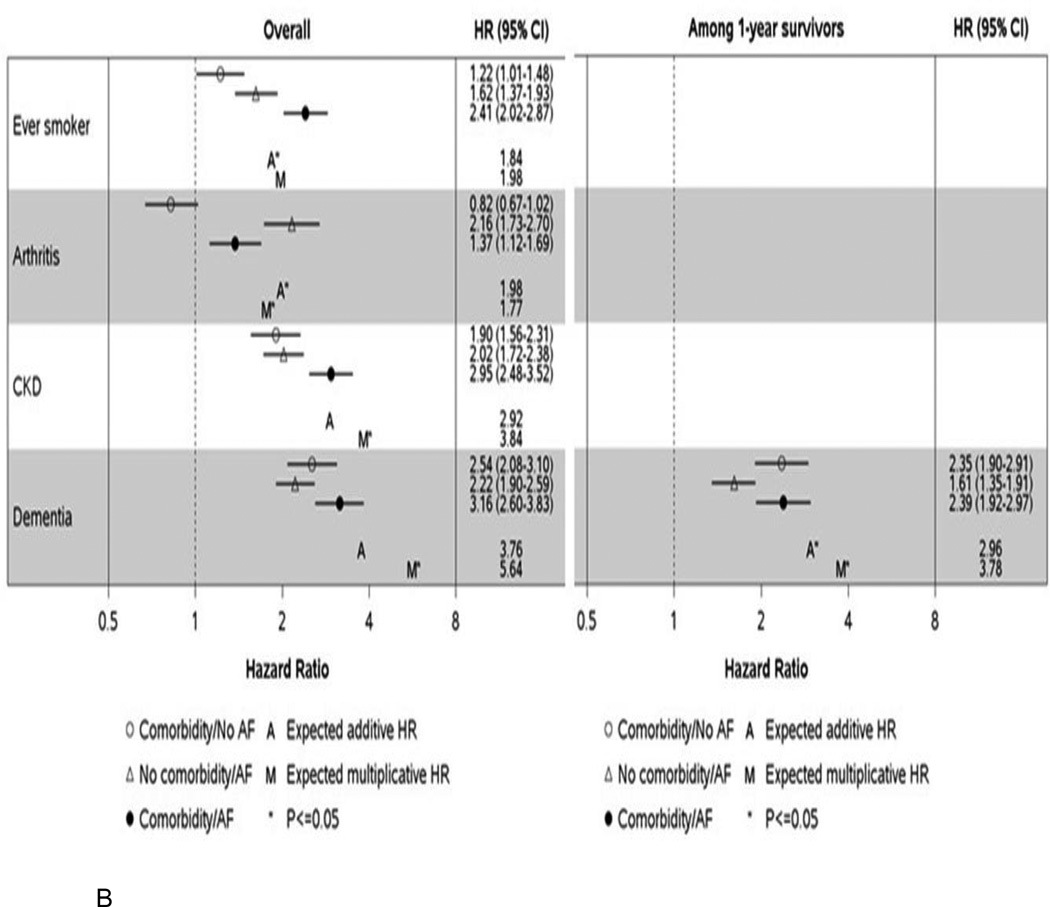

Figure 3.

Hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for hospitalization (Panel A) and death (Panel B) by presence of individual comorbidities in atrial fibrillation patients, after adjustment for age, sex, and all other comorbidities modeled as time-dependent variables. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CHF, congestive heart failure; CAD, coronary heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Additive and multiplicative interactions between AF case/control status and each comorbidity were tested to determine whether the presence of both a comorbidity and AF conferred a higher than expected risk of hospitalization or death. Where significant interactions (additive and/or multiplicative) were identified, the HRs for hospitalization (Figure 4a) and death (Figure 4b) are provided for combinations of comorbidity and AF case/control status with controls without the comorbidity serving as the referent group. For all comorbidities, HRs are presented regardless of whether a significant interaction was observed in Supplemental Tables III–VI.

Figure 4.

Hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for hospitalization (Panel A) and death (Panel B) by atrial fibrillation and comorbidity classification for significant additive and/or multiplicative interactions. Hazard ratios are adjusted for age, sex, and all other comorbidities modeled as time-dependent variables and are presented overall and among 1 year survivors. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CHF, congestive heart failure; CAD, coronary heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; AF, atrial fibrillation.

The expected hazard ratios were calculated as follows: Expected additive HR = HR10 + HR01 − 1. Expected multiplicative HR = HR10 × HR01. HR10 represents the HR for those with the comorbidity and no AF compared to those with no comorbidity/no AF; HR01 represents the HR for those without the comorbidity and AF compared to those with no comorbidity/no AF. If the observed HR is above the expected, then a synergistic effect on the risk of the outcome is observed for those with both AF and the comorbidity. Alternatively, an antagonistic effect may be observed where patients with both AF and the comorbidity experience a lower than expected risk of the outcome.

For hospitalizations, significant additive and/or multiplicative interactions were observed for 6 comorbidities: ever smoking, heart failure, coronary artery disease, arthritis, cancer, and dementia (Figure 4a). For 5 of the 6 conditions, the highest risk of hospitalization was observed among those with the comorbidity who also had AF. However, this pattern was not observed for dementia. For controls without AF, a higher risk of hospitalization was observed for those with dementia, whereas among AF cases, the risk of hospitalization was similar among those with and without dementia. Of note, the only synergistic effect (where the observed HR was above the expected) was for ever smoking. The observed HR for patients who were both ever smokers and who had AF (vs. never smokers without AF) was above the expected additive HR (HR 1.78 (1.56–2.02) observed vs. 1.52 expected). After restricting to 1-year survivors, significant interactions remained for 3 of the 6 conditions (arthritis, cancer, and dementia).

For death, significant interactions were observed between AF and ever smoking, arthritis, chronic kidney disease, and dementia (Figure 4b). Unexpectedly, arthritis appeared to have an inverse association with death in both AF cases and population controls. An increased risk of death was observed for both AF cases and controls who had dementia, but the relative difference in magnitude between those with and without dementia was greater in controls. Similar to the results for hospitalizations, a synergistic effect was observed where patients who were both ever smokers and who had AF experienced a greater risk of death than expected (HR 2.41 (2.02–2.87) observed vs. 1.84 expected additive HR). Among 1-year survivors, the only significant interaction was for dementia.

Discussion

AF patients have a higher prevalence of many chronic conditions compared to population controls. However, besides hypertension, comorbidities do not develop earlier in AF. Approximately half of AF is attributed to hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, obesity, and smoking. In addition, AF patients experience higher rates of hospitalization and death than those without AF. In AF, most comorbidities are associated with an increased risk of hospitalization, with heart failure and chronic kidney disease the strongest predictors of hospitalization. Fewer comorbidities are predictors of death, and include heart failure, chronic kidney disease, dementia, depression, ever smoking status, substance abuse, and cancer. Finally, AF patients who were ever smokers experienced higher than expected risks of hospitalization and death.

Risk Factors for Atrial Fibrillation: The Importance of Cardiovascular Health

We observed that patients with AF have a higher comorbidity burden, with 1 additional comorbid condition on average compared to community controls. Most conditions were more prevalent in AF cases than controls, except for some non-cardiovascular conditions including asthma, depression, dementia, osteoporosis, and schizophrenia. Despite the higher prevalence of most conditions in patients with AF, hypertension is the only condition that develops earlier in AF patients compared to controls.

Consistent with previous studies,27–29 hypertension was the risk factor with the highest attributable risk of AF. Our study found that coronary artery disease and congestive heart failure also had high attributable risks for AF, whereas others reported low attributable risks for these factors with body mass index27, 29 and smoking27 contributing more to AF risk. Huxley et al assessed optimal, borderline, and elevated levels of 5 selected AF risk factors – blood pressure, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, and prior cardiac disease (which included heart failure or coronary heart disease).27 They reported that having 1 or more elevated risk factor(s) explained 50% of AF (in other words, if all of the 5 risk factors were optimal/borderline, 50% of AF cases would be avoided).27 Although we used slightly different definitions of risk factors, our study similarly reported that 51% of AF would be avoided if our top 5 risk factors – hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, obesity, and smoking – were eliminated in the population.

Attributable risks reflect the amount of a disease that would be avoided if the risk factor were entirely eliminated from the population. However, eliminating all hypertension, all heart failure, or all of the top 5 AF risk factors in the population, for example, is not feasible. Thus, for our study, we also calculated the attributable risks in relation to a 25% or 50% reduction in risk factors, which is a more realistic goal. If a 25% reduction in the prevalence of 3 modifiable risk factors – hypertension, obesity, and smoking – were obtained, our estimates indicated that we could expect a 10% reduction in AF; if a 25% reduction in prevalence was obtained for these 3 risk factors, plus coronary artery disease and heart failure, a 17% reduction in AF would be expected. Although these estimates are less impressive than those reported for complete elimination of risk factors, it is important to underscore the low prevalence (<1%) of ideal cardiovascular health in the population30 and the putative impact of improving cardiovascular health on reducing cardiovascular disease. Indeed, with nearly 6 million Americans currently affected by AF and upwards of 12 million Americans expected to have AF by the year 2050,2–4 small reductions in risk factors would have a large absolute benefit in reducing new-onset AF in the population. Hence, reaching the 2020 American Heart Association Impact Goals, ‘to improve the cardiovascular health of all Americans by 20% while reducing deaths from cardiovascular diseases and stroke by 20%’31 would clearly favorably impact the occurrence of AF.

Multimorbidity and Outcomes in Atrial Fibrillation

AF patients experienced higher rates of hospitalization and death than community controls, which corroborates prior results.10–16 Patients with AF had a higher proportion of hospitalizations and deaths due to cardiovascular causes than those without AF, although a minority of hospitalizations and deaths in AF patients were due to cardiovascular causes, which is consistent with previous findings from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study10 and among AF patients aged 65 years and older in the MarketScan database.32 Interestingly, our rates of death due to cardiovascular diseases are higher than previously reported in the MarketScan database32 (42% vs. 32%), although these differences may be due to the capture of only inpatient deaths in the MarketScan database, whereas our study also captured out of hospital deaths.

In AF, the majority of comorbidities predict hospitalization, with an approximately 70% increased risk for those with heart failure and chronic kidney disease. Heart failure is a common comorbid condition among patients with AF and increases the risk of all-cause17, 18 and cardiovascular-related15, 17, 33 hospitalization in AF patients. In addition to heart failure, myocardial infarction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were the strongest predictors of cardiovascular-related hospitalization in the MarketScan and Geisinger Health Systems databases.15 While these comorbidities were associated with an increased risk of all-cause hospitalization in our study, the associations were weaker than those observed for heart failure. We found that patients with chronic kidney disease experienced a similar increased risk of hospitalization as patients with heart failure. However, previous studies have not assessed the impact of chronic kidney disease on hospitalizations in AF. For death, we observed an approximately 50% increased risk for those with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, dementia, depression, and ever smoking status. Heart failure, myocardial infarction, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were the strongest predictors of death in the Geisinger Health systems database,15 but coronary artery disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were not associated with death in our analyses after adjustment for all other comorbidities. Notably, obesity was not a risk factor for either hospitalization or death in AF patients, a finding somewhat at odds with the LEGACY study which showed that long-term sustained weight loss is associated with a reduction in AF burden and maintenance of sinus rhythm.34

Finally, our report delineates, to our knowledge for the first time, the combined joint effects of comorbidities with AF on outcomes. Ever smoking was the only comorbidity where combined with AF resulted in a greater than expected risk of hospitalization and death assuming additivity of effects. However, we did not adjust our interaction results for multiple comparisons; thus, our findings should be interpreted cautiously and additional studies should be conducted to determine whether similar associations are found in other populations. Nevertheless, given that smoking is a modifiable risk factor, invigorated efforts for smoking prevention and cessation are needed.

Limitations and Strengths

We acknowledge some limitations. First, because AF can be asymptomatic, it is possible that some controls may have had misdiagnosed AF. Second, there may have been some misclassification of the comorbidities due to perpetuation of codes after an error; however, it is unlikely differences in the misclassification would have been observed between AF cases and controls. Third, we did not have information on severity of comorbidities. Fourth, we did not adjust our results for multiple comparisons; thus, future studies may be warranted to confirm our results. Fifth, we may have missed some hospitalizations and deaths that occurred outside of Minnesota. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to all populations; however, the Olmsted County population is representative of the state of Minnesota and the Midwest region of the US.20 Despite these limitations, our data represent the experience of a community; the incorporation of data from multiple providers in Olmsted County, through the REP records-linkage system, allows nearly complete capture of patients’ medical history. In addition, we captured all hospitalizations occurring over a long follow-up and did not restrict to the first hospitalization or to hospitalizations only for AF or cardiovascular causes, which is particularly important given that we and others10, 32 have observed that the majority of hospitalizations in AF are due to non-cardiovascular causes.

Conclusion

Patients with AF have a higher prevalence of many comorbidities compared to those without AF. Hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, obesity, and smoking are the conditions with the largest attributable risk of AF, explaining approximately half of AF. Patients with AF also experience higher rates of hospitalization and death. However, despite the greater comorbidity burden in AF, the impact of comorbidities on hospitalization and death is generally not greater in AF patients compared to population controls, with the exception of smoking. AF patients who were ever smokers experienced higher than expected risks of hospitalization and death. The management of comorbidities in patients with AF, particularly modifiable risk factors, may improve outcomes in these patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Stotz, RN, and Dawn D. Schubert, RN for assistance with data collection, and Deborah S. Strain for secretarial assistance.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by grants from the American Heart Association (11SDG7260039) and the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG034676). Dr. Roger is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association. Additional support was provided by grant 16EIA26410001 from the American Heart Association (Alonso). The funding sources played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Alanna M. Chamberlain is a co-investigator on the Rochester Epidemiology Project (R01 AG034676).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and approved the submitted manuscript; the manuscript has not been submitted elsewhere nor published elsewhere in whole or in part. Conception or design: AMC, AA, SAW, VLR; Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: AMC, SAW, JMK, SMM, MB. Drafting of the manuscript: AMC, AA, SAW, VLR; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors; Statistical analysis: SAW, JMK; Obtaining funding: AMC

References

- 1.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285(18):2370–2375. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Cha SS, Bailey KR, Abhayaratna WP, et al. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation. 2006;114(2):119–125. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colilla S, Crow A, Petkun W, Singer DE, Simon T, Liu X. Estimates of current and future incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the U.S. adult population. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112(8):1142–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naccarelli GV, Varker H, Lin J, Schulman KL. Increasing prevalence of atrial fibrillation and flutter in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(11):1534–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alonso A, Krijthe BP, Aspelund T, Stepas KA, Pencina MJ, Moser CB, et al. Simple risk model predicts incidence of atrial fibrillation in a racially and geographically diverse population: the CHARGE-AF consortium. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(2):e000102. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamberlain AM, Agarwal SK, Folsom AR, Soliman EZ, Chambless LE, Crow R, et al. A clinical risk score for atrial fibrillation in a biracial prospective cohort (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities [ARIC] study) Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(1):85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schnabel RB, Sullivan LM, Levy D, Pencina MJ, Massaro JM, D'Agostino RB, Sr, et al. Development of a risk score for atrial fibrillation (Framingham Heart Study): a community-based cohort study. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):739–745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60443-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinner MF, Stepas KA, Moser CB, Krijthe BP, Aspelund T, Sotoodehnia N, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide and C-reactive protein in the prediction of atrial fibrillation risk: the CHARGE-AF Consortium of community-based cohort studies. Europace. 2014;16(10):1426–1433. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith JG, Newton-Cheh C, Almgren P, Struck J, Morgenthaler NG, Bergmann A, et al. Assessment of conventional cardiovascular risk factors and multiple biomarkers for the prediction of incident heart failure and atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(21):1712–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bengtson LG, Lutsey PL, Loehr LR, Kucharska-Newton A, Chen LY, Chamberlain AM, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on healthcare utilization in the community: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(6):e001006. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamberlain AM, Gersh BJ, Alonso A, Chen LY, Berardi C, Manemann SM, et al. Decade-long trends in atrial fibrillation incidence and survival: a community study. Am J Med. 2015;128(3):260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desai NR, Giugliano RP. Can we predict outcomes in atrial fibrillation? Clin Cardiol. 2012;35(Suppl 1):10–14. doi: 10.1002/clc.20989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim MH, Johnston SS, Chu B-C, Dalal MR, Schulman KL. Estimation of total incremental health care costs in patients with atrial fibrillation in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(3):313–320. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.958165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Bailey KR, Cha SS, Gersh BJ, Seward JB, et al. Mortality trends in patients diagnosed with first atrial fibrillation: a 21-year community-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(9):986–992. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panaccio MP, Cummins G, Wentworth C, Lanes S, Reynolds SL, Reynolds MW, et al. A common data model to assess cardiovascular hospitalization and mortality in atrial fibrillation patients using administrative claims and medical records. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:77–90. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S64936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piccini JP, Hammill BG, Sinner MF, Jensen PN, Hernandez AF, Heckbert SR, et al. Incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation and associated mortality among Medicare beneficiaries, 1993–2007. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(1):85–93. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.962688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinberg BA, Kim S, Fonarow GC, Thomas L, Ansell J, Kowey PR, et al. Drivers of hospitalization for patients with atrial fibrillation: results from the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF) Am Heart J. 2014;167(5):735–742. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapa DW, Akintade B, Schron E, Friedmann E, Thomas SA. Is health-related quality of life a predictor of hospitalization or mortality among women or men with atrial fibrillation? J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;29(6):555–564. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.St. Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(2):151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.St. Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(9):1059–1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.St. Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Pankratz JJ, Brue SM, et al. Data resource profile: the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(6):1614–1624. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodman RA, Posner SF, Huang ES, Parekh AK, Koh HK. Defining and measuring chronic conditions: imperatives for research, policy, program, and practice. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E66. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC: 2010. Dec, Multiple chronic conditions - a strategic framework: optimum health and quality of life for individuals with multiple chronic conditions. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson WB. ASA-SIAM Series on Statistics and Applied Probability. Philadelphia, PA: 2003. Recurrent events data analysis for product repairs, disease recurrence, and other applications. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li R, Chambless L. Test for additive interaction in proportional hazards models. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(3):227–236. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huxley RR, Lopez FL, Folsom AR, Agarwal SK, Loehr LR, Soliman EZ, et al. Absolute and attributable risks of atrial fibrillation in relation to optimal and borderline risk factors: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 2011;123(14):1501–1508. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez CJ, Soliman EZ, Alonso A, Swett K, Okin PM, Goff DC, Jr, et al. Atrial fibrillation incidence and risk factors in relation to race-ethnicity and the population attributable fraction of atrial fibrillation risk factors: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(2):71–76. 76 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schnabel RB, Yin X, Gona P, Larson MG, Beiser AS, McManus DD, et al. 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study. The Lancet. 2015;386(9989):154–162. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61774-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(7):e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naccarelli GV, Johnston SS, Dalal M, Lin J, Patel PP. Rates and implications for hospitalization of patients >/=65 years of age with atrial fibrillation/flutter. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(4):543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva-Cardoso J, Zharinov OJ, Ponikowski P, Naditch-Brule L, Lewalter T, Brette S, et al. Heart failure in patients with atrial fibrillation is associated with a high symptom and hospitalization burden: the RealiseAF survey. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36(12):766–774. doi: 10.1002/clc.22209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Meredith M, Mehta AB, Mahajan R, Wong CX, et al. Long-term effect of goal-directed weight management in an atrial fibrillation cohort: a long-term follow-up study (LEGACY) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(20):2159–2169. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.