ABSTRACT

Objective:

The halo sign consists of an area of ground-glass opacity surrounding pulmonary lesions on chest CT scans. We compared immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients in terms of halo sign features and sought to identify those of greatest diagnostic value.

Methods:

This was a retrospective study of CT scans performed at any of seven centers between January of 2011 and May of 2015. Patients were classified according to their immune status. Two thoracic radiologists reviewed the scans in order to determine the number of lesions, as well as their distribution, size, and contour, together with halo thickness and any other associated findings.

Results:

Of the 85 patients evaluated, 53 were immunocompetent and 32 were immunosuppressed. Of the 53 immunocompetent patients, 34 (64%) were diagnosed with primary neoplasm. Of the 32 immunosuppressed patients, 25 (78%) were diagnosed with aspergillosis. Multiple and randomly distributed lesions were more common in the immunosuppressed patients than in the immunocompetent patients (p < 0.001 for both). Halo thickness was found to be greater in the immunosuppressed patients (p < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Etiologies of the halo sign differ markedly between immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients. Although thicker halos are more likely to occur in patients with infectious diseases, the number and distribution of lesions should also be taken into account when evaluating patients presenting with the halo sign.

Keywords: Tomography, X-ray computed; Aspergillosis; Lung neoplasms

RESUMO

Objetivo:

O sinal do halo consiste em uma área de opacidade em vidro fosco ao redor de lesões pulmonares em imagens de TC de tórax. Pacientes imunocompetentes e imunodeprimidos foram comparados quanto a características do sinal do halo a fim de identificar as de maior valor diagnóstico.

Métodos:

Estudo retrospectivo de tomografias realizadas em sete centros entre janeiro de 2011 e maio de 2015. Os pacientes foram classificados de acordo com seu estado imunológico. Dois radiologistas torácicos analisaram os exames a fim de determinar o número de lesões e sua distribuição, tamanho e contorno, bem como a espessura do halo e quaisquer outros achados associados.

Resultados:

Dos 85 pacientes avaliados, 53 eram imunocompetentes e 32 eram imunodeprimidos. Dos 53 pacientes imunocompetentes, 34 (64%) receberam diagnóstico de neoplasia primária. Dos 32 pacientes imunodeprimidos, 25 (78%) receberam diagnóstico de aspergilose. Lesões múltiplas e distribuídas aleatoriamente foram mais comuns nos imunodeprimidos do que nos imunocompetentes (p < 0,001 para ambas). A espessura do halo foi maior nos imunodeprimidos (p < 0,05).

Conclusões:

As etiologias do sinal do halo em pacientes imunocompetentes são bastante diferentes das observadas em pacientes imunodeprimidos. Embora halos mais espessos ocorram mais provavelmente em pacientes com doenças infecciosas, o número e a distribuição das lesões também devem ser levados em conta na avaliação de pacientes que apresentem o sinal do halo.

INTRODUCTION

The CT halo sign consists of an area of ground-glass opacity surrounding a pulmonary nodule or mass. 1 The halo sign was first described in 1985 by Kuhlman et al., who reviewed chest CT scans of nine patients with acute leukemia who developed invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. 2 Since then-and despite its infrequency-the halo sign has been reported in association with a variety of conditions. 3 , 4 Its pathophysiology usually involves one of three mechanisms: hemorrhage, inflammation, or neoplastic growth. 5

Most of the available information about the halo sign has been derived from patients with pre-existing conditions. However, there are limited data on its potential usefulness in predicting the final diagnosis (or diagnostic group, e.g., infection or malignancy). Therefore, the objective of the present study was to determine the diagnostic value of the halo sign by exploring associations between CT measurements and immunological status in a cohort of patients presenting with the CT halo sign.

METHODS

This was a multicenter retrospective study of CT images obtained between January of 2010 and May of 2014 from patients presenting at any of seven tertiary care centers in southern Brazil, which is an endemic area for granulomatous diseases. Scans were selected by searching the picture archiving and communication systems (PACSs) of all participating institutions using the terms "halo" and "halo sign", as well as the following combinations of terms: "ground-glass" + "nodule"; "nodule" + "surround"; "nodule" + "periphery"; and "ground-glass" + "periphery". The research protocol was approved by the local research ethics committee (Protocol no. 243.155). Given the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was waived.

A general radiologist reviewed the files retrieved from the PACSs in order to confirm the presence of the halo sign. Medical records were reviewed in order to determine patient immune status. For the purpose of the present study, patients were considered immunosuppressed in the presence of AIDS; any form of congenital immunodeficiency; or a recent (≤ two-month) history of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or decreased white blood cell count (lymphopenia [absolute lymphocyte count ≤ 1.0 × 109 L] or neutropenia [absolute neutrophil count ≤ 1.5 × 109 L]). 6 , 7 All other patients were considered to be immunocompetent. If a final diagnosis had not been reached by the time of medical record review, patients were followed until a definitive diagnosis was made, with serological, histological, or microbiological confirmation. Histological sampling varied across the participating institutions, including transthoracic needle biopsy, video-assisted thoracotomy, and open thoracotomy. Although serological and microbiological tests were performed in accordance with the corresponding (updated) guidelines, their performance was dependent on patient clinical background.

All CT scans were performed with multidetector scanners with at least 16 rows of detectors, the acquisition parameters being as follows: slice thickness, ≤ 1.25 mm; rotation time, 0.5 s; voltage, 120 kV; and electric current, 150-400 mA. Automatic exposure control was enabled. No contrast medium was used.

For each examination, the number of lesions, as well as their outline (regular vs. irregular), size, and distribution, together with any other associated findings, were recorded. The criteria for CT findings were those defined in the Fleischner Society Glossary of Terms. 1 A nodule was defined as a rounded or irregular opacity that was well or poorly defined and ≤ 3 cm in diameter. Mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes range in size from sub-CT resolution to 10 mm. A cavity was defined as a gas-filled space, seen as a lucency or low-attenuation area within a pulmonary consolidation, mass, or nodule. The tree-in-bud pattern refers to centrilobular branching structures that resemble a budding tree. Ground-glass opacities were defined as hazy areas of increased opacity or attenuation with no obscuration of the underlying vessels. Consolidation was defined as homogeneous opacification of the parenchyma with obscuration of the underlying vessels. Abnormalities were classified as being located in the upper lobes, located in the lower lobes, or randomly distributed.

The CT scans were independently reviewed in random order by two chest radiologists who had more than 10 years of experience and who were blinded to patient clinical information. Subsequently, the two aforementioned radiologists and a third chest radiologist (with more than 40 years of experience) together reviewed the scans in order to make a final consensus decision. The diameters of the nodules and halos were measured at their widest points on axial CT scans with lung window settings.

Microsoft Excel was used for data storage and descriptive analysis, and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), was used for correlations. The chi-square test was used for qualitative variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used in order to determine whether quantitative data were normally distributed. For parametric variables, the Student's t-test was used. For nonparametric variables, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. All tests were two-tailed, and a significance level of 0.05 was used throughout.

RESULTS

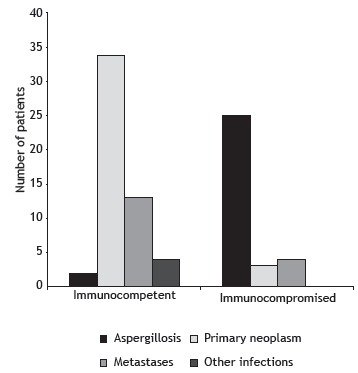

Of the 20,210 CT examinations retrieved from the PACSs of the participating centers, 85 cases (0.42%) were selected for inclusion in the present study. Of those 85 patients, 46 were male. In addition, 32 were classified as being immunosuppressed at the time of CT examination, and 53 were immunocompetent. Of those, 34 (64%) were diagnosed with a primary malignancy; of those, 24 had histopathologically confirmed adenocarcinoma. Of the 32 patients who were classified as being immunosuppressed, 25 (78%) had findings suggestive of invasive aspergillosis (positive results on direct mycological examination or histological findings). All but one of the immunosuppressed patients presenting with invasive aspergillosis were found to have neutropenia. In addition, 7 of those 25 were diagnosed with proven invasive fungal disease (on the basis of specimen culture results and radiological findings), and 18 were diagnosed with probable invasive aspergillosis (on the basis of positive microbiological studies and radiological findings). 8 Other causes of the CT halo sign included metastases, lymphoproliferative diseases, tuberculosis, plasmacytoma, staphylococcal pneumonia, actinomycosis, cryptococcosis, and histiocytosis. Table 1 and Figure 1 show the frequencies of these diagnoses in the two study groups.

Table 1. Etiology of the CT halo sign, by patient immune status.a .

| Variable | Immunocompetent patients (n = 53) | Immunocompromised patients (n = 32) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary neoplasm | 34 (64) | - |

| Invasive aspergillosis | - | 25 (78) |

| Metastases | 13 (25.0) | 2 (6.3) |

| Lymphoproliferative diseases | - | 3 (9.4) |

| Tuberculosis | 2 (3.8) | - |

| Plasmacytoma | - | 2 (6.3) |

| Staphylococcal pneumonia | 1 (1.8) | - |

| Actinomycosis | 1 (1.8) | - |

| Cryptococcosis | 1 (1.8) | - |

| Histiocytosis | 1 (1.8) | - |

Data presented as n (%).

Figure 1. Bar chart showing final diagnosis in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients presenting with the CT halo sign.

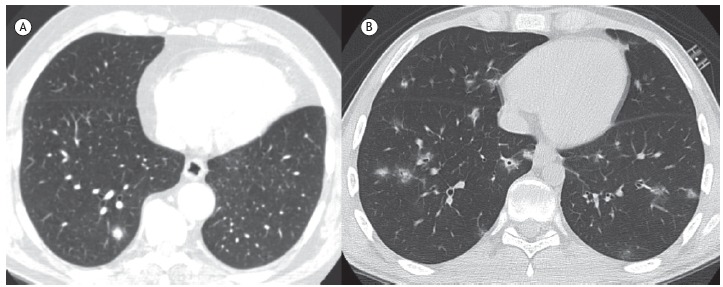

The number and distribution of lesions on CT scans were found to vary significantly according to patient immune status, with immunosuppressed patients tending to exhibit multiple and randomly distributed lesions (Table 2). In cases of multiple lesions, halo thickness tended to be greater (≥ 9 mm) in immunosuppressed patients (p < 0.05; Figure 2); the same was not true for single lesions (p = 0.299).

Table 2. Demographic data and CT findings, by patient immune status.a .

| Total | Immunocompetent patients (n = 53) | Immunocompromised patients (n = 32) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||||

| Male genderb | 46 (54) | 29 (55) | 17 (53) | 0.887 |

| Age, years | 53 ± 17 | 55 ± 14 | 48 ± 21 | 0.135 |

| CT findings | ||||

| Number of nodulesc | 3 (1-16) | 2 (1-15) | 5 (1-16) | < 0.001 |

| 1b | 41 (48) | 38 (72) | 3 (9) | < 0.001 |

| > 1b | 44 (52) | 15 (28) | 29 (91) | |

| Nodule outlineb,* | ||||

| Regular | 46 (54) | 31 (58) | 15 (47) | 0.298 |

| Irregular | 39 (46) | 22 (42) | 17 (53) | |

| Nodule size, mm† | ||||

| Solitary nodule | 25 ± 13 | 26 ± 14 | 16 ± 9 | 0.231 |

| Largest nodule | 16 ± 8 | 12 ± 8 | 19 ± 7 | 0.805 |

| Smallest nodule | 6 ± 3 | 6 ± 4 | 5 ± 2 | 0.007 |

| Halo thickness, mm† | ||||

| Solitary nodule | 7 ± 3 | 7 ± 3 | 5 ± 1 | 0.299 |

| Largest nodule | 8 ± 4 | 5 ± 2 | 9 ± 4 | 0.001 |

| Smallest nodule | 5 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 | 0.002 |

| Lesion distributionb | ||||

| Random | 47 (55) | 15 (28) | 28 (91) | < 0.001 |

| Upper lobe | 23 (27) | 23 (44) | 1 (3) | < 0.001 |

| Lower lobe | 15 (18) | 15 (28) | 2 (6) | 0.003 |

| Associated findingsb | ||||

| Consolidation | 5 (63) | - | 5 (100) | 0.016 |

| Tree-in-bud pattern | 2 (25) | 2 (67) | - | |

| Cavitated nodules | 1 (12) | 1 (33) | - | |

| Diagnostic confirmation (n = 105)b,‡ | ||||

| Serological | 30 (30) | 4 (7) | 26 (53) | < 0.001 |

| Microbiological | 22 (20) | 2 (4) | 20 (41) | < 0.001 |

| Histological | 53 (50) | 50 (89) | 3 (6) | < 0.001 |

Data presented as mean ± SD, except where otherwise indicated. bData presented as n (%). cData presented as median (range). *For nodules presenting with a peripheral halo sign. †For patients with multiple lesions, data for the largest and smallest lesions are displayed separately. ‡The number of diagnostic confirmations exceeds the number of cases because some diagnoses were confirmed by more than one method.

Figure 2. In A, axial CT scan of the chest of an asymptomatic, immunocompetent 54-year-old male patient, showing a right lower lobe pulmonary nodule surrounded by areas of ground-glass opacity (the CT halo sign); the final diagnosis was primary adenocarcinoma. In B, axial CT scan of the chest of an immunosuppressed 19-year-old male patient, showing multiple, randomly distributed pulmonary nodules surrounded by ground-glass opacities (the CT halo sign); the final diagnosis was aspergillosis.

DISCUSSION

The present retrospective study revealed ten different etiologies of the CT halo sign in 85 individuals. Pathological findings of tumor cells, inflammatory infiltrates, and, most commonly, alveolar hemorrhage have been reported to account for the ground-glass opacities surrounding pulmonary lesions on CT scans. 4 , 9 Although the halo sign has been causally associated with numerous other conditions, its presence is generally more helpful than challenging. 9 Studies involving immunocompromised patients have confirmed the diagnostic value of the halo sign, demonstrating that its specificity increases as patient immune status deteriorates. 10 , 11 However, most available evidence consists of descriptive data. To our knowledge, the present study was the first to address the correlations between the halo sign and patient immune status. In addition, our study demonstrated that thicker halos are associated with infectious diseases, whereas thinner halos are associated with neoplastic diseases. In agreement with the results of previous studies, the results of the present study showed that adenocarcinoma and pulmonary aspergillosis were the conditions that were most commonly associated with the halo sign in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients, respectively. 4 , 12 In cases of multiple pulmonary nodules, halo thickness tended to be greater in immunocompromised patients than in immunocompetent patients. This finding is consistent with those of a study investigating characteristics of the reversed halo sign, in which greater rim thickness was associated with invasive fungal infection. 13 The same cannot be concluded for solitary nodules, and this is possibly due to a statistically insufficient number of single lesions among the immunosuppressed patients (i.e., only three).

According to Gao et al., the relationships between ground-glass lung nodules and adjacent blood vessels can aid in establishing a final diagnosis based on the presence and degree of vascular distortion. 14 This is particularly relevant for immunocompetent patients presenting with the CT halo sign. In the present study, a neoplastic etiology was found to be more common in the immunocompetent patients than in the immunosuppressed patients. However, given the reduced halo thickness in the former and the variety of possible pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the halo sign, further studies are needed in order to determine whether this correlation can be extrapolated to smaller areas of ground-glass opacities.

Our study has some limitations. First, the retrospective nature of the study increases the likelihood that medical record inaccuracies affected our results. Second, the relatively small sample size did not allow us to perform an analysis of covariance in order to determine the combined contribution of halo sign features in predicting the final diagnosis. Third, dynamic changes observed in the long-term evaluation of the appearance of the halo sign, particularly in cases of infectious disease, might have affected some of our results. Finally, the definition of immunosuppression used in our study might be in disagreement with the constant improvements in the toxicity of chemotherapy and radiation therapy; however, that definition was adopted for research purposes only, and many other clinical parameters should be taken into account in a more practical scenario.

In summary, our findings are consistent with available data on the etiologies of the CT halo sign in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients. Given the differences in radiological presentation between these two groups of patients, appropriate assessment of halo sign features can be useful in clinical investigation. A diagnosis of primary neoplasm appears to be common among immunocompetent patients, as does a diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis among immunosuppressed patients. Thicker halos are associated with infectious diseases, whereas thinner halos are associated with neoplastic diseases; the number and distribution of lesions should also be taken into account, given that they can predict the final diagnosis.

Footnotes

Study carried out at the Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre (RS) Brasil.

Financial support: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246(3):697–722. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462070712. http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2462070712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhlman JE, Fishman EK, Siegelman SS. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in acute leukemia characteristic findings on CT, the CT halo sign, and the role of CT in early diagnosis. Radiology. 1985;157(3):611–614. doi: 10.1148/radiology.157.3.3864189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/radiology.157.3.3864189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee YR, Choi YW, Lee KJ, Jeon SC, Park CK, Heo JN. CT halo sign the spectrum of pulmonary diseases. Br J Radiol. 2005;78(933):862–865. doi: 10.1259/bjr/77712845. http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/bjr/77712845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim Y, Lee KS, Jung KJ, Han J, Kim JS, Suh JS. Halo sign on high resolution CT findings in spectrum of pulmonary diseases with pathologic correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23(4):622–626. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199907000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parrón M, Torres I, Pardo M, Morales C, Navarro M, Martínez-Schmizcraft M. The halo sign in computed tomography images differential diagnosis and correlation with pathology findings [Article in Spanish]. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2008;44(7):386–392. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0300-2896(08)70453-8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng WL, Chu CM, Wu AK, Cheng VC, Yuen KY. Lymphopenia at presentation is associated with increased risk of infections in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. QJM. 2006;99(1):37–47. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hci155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hci155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valent P. Low blood counts immune mediated, idiopathic, or myelodysplasia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2012;2012:485–491. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.485. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(12):1813–1821. doi: 10.1086/588660. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/588660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinto PS. The CT Halo Sign. Radiology. 2004;230(1):109–110. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2301020649. http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2301020649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Escuissato DL, Gasparetto EL, Marchiori E, Rocha Gde M, Inoue C, Pasquini R. Pulmonary infections after bone marrow transplantation high-resolution CT findings in 111 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185(3):608–615. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.3.01850608. http://dx.doi.org/10.2214/ajr.185.3.01850608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blum U, Windfuhr M, Buitrago-Tellez C, Sigmund G, Herbst EW, Langer M. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis MRI, CT, and plain radiographic findings and their contribution for early diagnosis. Chest. 1994;106(4):1156–1161. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.4.1156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.106.4.1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaeta M, Blandino A, Scribano E, Minutoli F, Volta S, Pandolfo I. Computed tomography halo sign in pulmonary nodules frequency and diagnostic value. J Thorac Imaging. 1999;14(2):109–113. doi: 10.1097/00005382-199904000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marchiori E, Marom EM, Zanetti G, Hochhegger B, Irion KL, Godoy MC. Reversed halo sign in invasive fungal infections criteria for differentiation from organizing pneumonia. Chest. 2012;142(6):1469–1473. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-0114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao F, Li M, Ge X, Zheng X, Ren Q, Chen Y. Multi-detector spiral CT study of the relationships between pulmonary ground-glass nodules and blood vessels. Eur Radiol. 2013;23(12):3271–3277. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2954-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00330-013-2954-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]