Abstract

We assessed the roles of perceived satisfaction and perceived danger and vaping-product-type as correlates of more frequent use of vaping products. In a baseline assessment of a longitudinal study of US Army Reserve/National Guard Soldiers and their partners (New York State, USA, 2014–2016), participants were asked about current use of vaping products (e-cigarettes) and perceived satisfaction and danger in comparison to cigarettes as well as type of product used. Fisher-exact tests and multiple ordinal logistic regressions were used. In multivariable and univariate models, more perceived satisfaction, less perceived danger, and use of non-cig-alike products were associated with more frequent use of vaping products (ps < 0.05, two-tailed). For self-selected, more frequent adult users, e-cigs can be at least as satisfying as cigarettes and often more satisfying and are perceived as less dangerous than cigarettes. Non-cig-alike products were more likely in daily users. Some concern that e-cigs are a gateway to cigarettes arises from assuming that e-cigs may not be as reinforcing and pleasurable as cigarettes. These results indicate that accurate perception of comparative risk and use of more effective-nicotine delivery product can produce for some users a highly-satisfying alternative to cigarettes.

Keywords: Electronic cigarettes, Vaping, Cigarettes, Perceived risk, Satisfaction, Harm reduction

Highlights

-

•

Daily users of e-cigarettes found them at least as satisfying as cigarettes.

-

•

Satisfaction from e-cigarettes was more likely in more frequent users.

-

•

All daily users reported them as less dangerous than cigarettes.

-

•

Perceived danger from e-cigarettes was higher in less frequent users.

-

•

Daily users of e-cigarettes were more likely to be using non-cig-alikes.

1. Introduction

The rising use of vaping products (i.e., e-cigarettes, electronic cigarettes and other vaping products) has been of great interest to public health authorities (Royal College of Physicians, 2016). Use of these products has increased dramatically (Miech et al., 2016). Among high school students in the United States, past 30 day use of e-cigarettes rose from 1.5% in 2011 to 16.0% in 2015 (Singh et al., 2016). One concern has been that vaping products could be serving as a gateway to the uptake of cigarette use (Bell and Keane, 2014, Kozlowski and Warner, 2017). This concern is supported by the belief that these products are not as satisfying to smokers as cigarettes and that cigarettes would provide a much more satisfying experience. One report of use of e-cigarettes by college students in New York State found that “enjoyment” was a strong correlate of daily use (Saddleson et al., 2016). We wanted to further explore the role of enjoyment or satisfaction from the product as a predictor of more frequent use. To do so, we employed direct comparative questions (Kozlowski et al., 2000, Kozlowski et al., 1989b) as an efficient technique for assessing how users compared the satisfaction they received from smoking cigarettes with the satisfaction from vaping products.

Though not without risk, e-cigarettes had been judged to be at least 90% less harmful than cigarettes (McNeill et al., 2015, Nutt et al., 2014). In contrast, a national survey showed that about 50% of adults report that e-cigarettes are at least as harmful as cigarettes (Kiviniemi and Kozlowski, 2015). Another national survey has found that from 2012 to 2015, the percentage of adults who reported e-cigarettes as less harmful than cigarettes has decreased, indicating a trend toward inaccurate beliefs being more common (Majeed et al., 2016). Given the widespread confusion about the dangers of vaping compared to cigarettes (Tan et al., 2016, Zulkifli et al., 2016), we also wanted to explore the relation of perceived danger to likelihood of use.

In addition to the differences in perception that might reasonably influence use of vaping products, we wanted to assess the role of product differences in influencing frequency of use. The nature of vaping products has been changing greatly, with evidence that the early, so called first generation devices that resembled cigarettes (also known as cig-alike products) generally deliver lower levels of nicotine to the user than new open systems with high-capacity batteries and electronic circuits linked to refillable atomizers (Farsalinos et al., 2014). To the extent nicotine delivery is a determinant of use, we expected that the second generation products would be more likely to be used by the more frequent users.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample

The Operation: SAFETY Study (Soldiers And Families Excelling Through the Years) is a longitudinal research study examining the health and well-being of U.S. Army Reserve/National Guard Soldiers and their partners (N = 411 couples). More details on the Operation: SAFETY project are available in Heavey et al. (2017). Participants used a self-guided, computer-assisted self-interview, conducted between August 2014 and January 2016, to respond to all questionnaires. Assessments take approximately 2–3 h and can occur at the University at Buffalo Center for Health Research or online via a secure assessment portal. This study is approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained. For this report, we used a subsample of the overall sample based upon current use of e-cigarettes. There were 105 adults (53 males, 52 females) 18.5 to 44.9 years old (mean = 30.2; SD = 6.56). Race/ethnicity was predominately Non-Hispanic White (83%) with 8% Non-Hispanic Black, 6% Hispanic and 8% other. Participants were well educated with the majority having had some college experience (64%) or completion of a college degree (15%) while the remaining held high school diplomas (18%) or less education (3%).

2.2. Measures

Cigarette smoking was assessed using two questions: “In your entire life, have you ever smoked 100 cigarettes?” (Answers: Yes or No.) Those who said Yes were asked: “Do you currently smoke cigarettes? (Answers: No, I quit smoking or Yes, I currently smoke cigarettes.)

All participants were asked: “In your entire life, have you ever used an electronic cigarette, an e-cigarette, or vaping device (these battery-powered devices produce vapor, often with nicotine, instead of smoke)? There are many types of e-cigarettes. Some common brands include Smoking Everywhere, NJOY, Blu, Vapor King, Pax, and Firefly.” (Answers: Yes or No.) Those who answered Yes were asked: “Do you currently use e-cigarettes or a vaping device?” (Answers: every day (Daily users = scored 3), some days (Not Daily users = 2), not at all (Triers = 1)).

Initially, only Daily users and Not Daily users of e-cigarettes were asked the following questions, but then the procedure was changed to ask these questions also of the Triers who were not using currently. This means that the true percentage of those who were not current users of e-cigarettes is under-estimated: 147 participants who were Triers were not asked the perceived satisfaction or perceived danger questions. These were the key questions:

Is your favorite e-cigarette or vaping device more or less satisfying than your favorite cigarette? Answers scored from 1 to 5, with 1) “My favorite e-cig or vaping device is much less satisfying than my favorite cigarette,” [the sentences were written out in full, but the only wording change is indicated in the following], 2) “… a little less …”, 3) “… about as… “, 4) “…a little more…”, 5) …much more…”.

Is your favorite e-cigarette or vaping device more or less dangerous for your health than your favorite cigarette? Answers scored 1 to 5, with 1) “My favorite e-cig or vaping device is much less dangerous than my favorite cigarette,” [all sentences were written out in full, but the only wording change is indicated in the following], 2) “… a little less…”, 3) “... about as… “, 4) “… a little more…”, 5) …much more…”.

The next question was open ended: “Name your favorite e-cig or vaping device (be as specific as you can).”

2.3. Scoring of type of vaping product used

The open-ended responses to type of product used were scored. For non-current users, most left it blank or said ‘don't know’, sometimes referring to the fact that they had just tried one once from a friend. Common products like Blu®, NJoy® were judged likeliest to be cig-a-likes. Scoring was done by looking at this question only with no reference to responses to other questions: 67 responses could be scored as to type. The score employed a two-level distinction: cig-alike (scored 1) or other than a cig-alike (including mods, tanks, vape pens) (scored 2). No questions were asked on nicotine use in the products or flavors.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics and Fisher-exact tests (two-tailed) were used. For the Fisher-exact tests, satisfaction scores were recoded: 1 = about as satisfying/a little more satisfying/much more satisfying and 2 = less satisfying/a little less satisfying; danger scores were recoded: 1 = a little less dangerous/much less dangerous and 2 = about as dangerous/a little more dangerous/much more dangerous. Multivariable ordinal logistic regression analyses (Stata 13.1, StataCorp, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, Texas 77845) were conducted to assess the association between regularity of vaping product usage (Triers = 1, Not Daily users = 2, and Daily users = 3) and a) perceived satisfaction from vaping in comparison to cigarettes (scored as indicated in the question above), b) perceived danger from vaping in comparison to cigarettes (scored as indicated in the question above), and 3) the type of vaping product used.

3. Results

3.1. Evidence of lack of bias in the samples of Triers who were or were not asked about perceptions

Since initially e-cigarette Triers were not asked about perceived satisfaction or perceived danger, we assessed if these individuals (N = 147) were different from those in this group who were asked the perception questions (N = 61). No statistically-significant differences were found in age, sex, or education (all ps > 0.05, two-tailed).

3.2. Perceptions of satisfaction

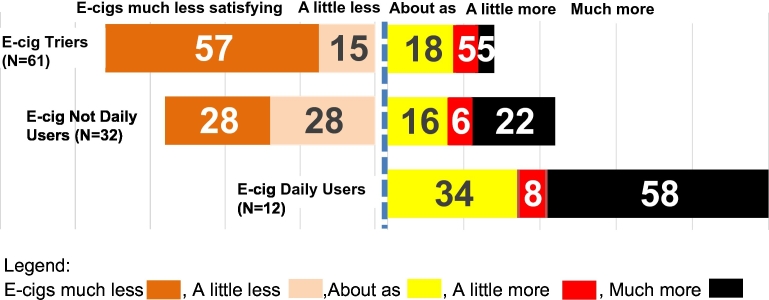

Fig. 1 shows the results in detail and shows that all daily users reported e-cigarettes as at least as satisfying as cigarettes, with 58% reporting vape as much more satisfying. Fisher exact tests (two-tailed) were done on recoded data. Satisfaction scores (recoded to e-cigarettes being about as satisfying as or more satisfying than cigarettes versus less satisfying than cigarettes) showed greater satisfaction in Daily users versus Not Daily users (p = 0.001) and Daily users versus Triers (p < 0.001); no difference between Not Daily users versus Triers = 0.17 (ns.); and greater satisfaction from e-cigarettes when comparing Any current use (Daily users + Not Daily users) versus Triers p = 0.002.

Fig. 1.

Is your favorite e-cigarette or vaping device more or less satisfying than your favorite cigarette? Answers are in percentages and abbreviated options are presented. Details are available in Methods section (New York State, USA, 2014–2016).

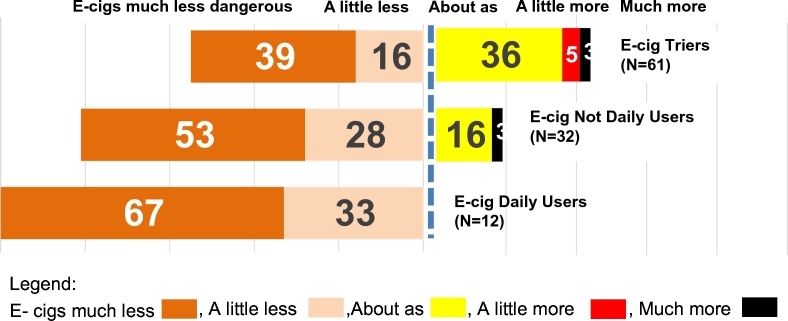

3.3. Perceptions of danger

Fig. 2 shows that perception of danger from e-cigarettes decreases as frequency of use increases. Fisher-exact tests were done on recoded data. Perceived danger was recoded to e-cigarettes being less dangerous than cigarettes versus as dangerous as or more dangerous than cigarettes. Daily users versus Not Daily users were not different (p = 0.167, (ns.)); Not Daily users were less likely to perceive danger than were Triers (p = 0.02); any current use (Daily users + Not Daily users) were less likely than Triers to perceive danger from e-cigarettes in comparison to cigarette (p = 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Is your favorite e-cigarette or vaping device more or less dangerous for your health than your favorite cigarette? Answers are in percentages and abbreviated options are presented. Details are available in Methods section (New York State, USA, 2014–2016).

3.4. Type of product used

Triers were most likely to report using Cig-alike products (84%, 26 of 31). Daily users were less likely (33%, 8 of 24) than Triers to use a Cig-alike (Fisher exact, p < 0.001); Daily users were less likely (8%, 1 of 12) than Triers to use Cig-alikes (p < 0.01). There was not a reliable difference (p > 0.05) in use of Cig-alikes between the Daily users and Not Daily users. Note that many of the Triers (49%) could not be scored as to type of product tried; 75% of the Not Daily users could be scored; 100% of Daily users could be scored.

3.5. Multivariable models

See Table 1. Increased perceived satisfaction from e-cigarettes (Odds ratio = 2.14, 95% CL: 1.57–2.91) was associated with greater frequency of use. Decreased perceived danger from e-cigarettes (Odds ratio = 0.51, 95% CL: 0.32–0.80) was associated with greater frequency of use. The associations held when the type of product used was added to the model (although the sample size, especially for Triers decreased considerably), but use of non-cig-alike products were associated with increased frequency of use. When product-type was added to the model, older participants were found to be somewhat likelier to use e-cigarettes more frequently, but other associations were comparable to those found in the model with product-type.

Table 1.

Two ordinal logistic regression models predicting use of e-cigarettes (1 = Triers, 2 = Not Daily users, 3 = Daily users); Product-type was determinable for only 67 participants (New York State, USA, 2014–2016).

| Variables | Odds ratio | 95% CL (N = 105) | p = | Odds ratio | 95% CL (N = 67) | p = |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.03 | 0.96–1.09 | 0.401 | 1.09 | 1.01–1.19 | 0.038 |

| Sex | 1.06 | 0.46–2.43 | 0.899 | 1.65 | 0.52–5.20 | 0.395 |

| Satisfaction | 2.14 | 1.57–2.91 | 0.000 | 2.00 | 1.31–3.07 | 0.001 |

| Danger | 0.51 | 0.32–0.80 | 0.004 | 0.33 | 0.14–0.73 | 0.007 |

| Product-type | – | – | – | 24.23 | 5.66–103.65 | 0.000 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Considerable satisfaction possible

This cross-sectional study does demonstrate that many self-selected daily users of vaping products (here 100% of them) can find these products at least about as satisfying as cigarettes and the majority (58%) found them to be “much more satisfying than cigarettes.” Some policies have been influenced by the belief that e-cigarettes are fundamentally lacking in satisfaction in comparison to cigarettes (Benowitz et al., 2017) and that there needs to be a push to get smokers to switch to these products. The belief that vaping does not represent a satisfying product (in comparison to cigarettes) would also support concerns that e-cigarette use could constitute a causal ‘gateway’ to cigarettes. A recent study in individuals with serious mental illness asked about satisfaction from e-cigarettes in comparison to cigarettes on a 5-point Likert-type scale and found very high satisfaction (averaging “4”) during the last 2 weeks of the study (Pratt et al., 2016). The related concept of “enjoyment” has been found to be an important correlate of regular use of e-cigarettes (Saddleson et al., 2016). Although there is some indication of causal gateway effects (e.g., (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2016)), the effects have been small with limited controls for confounding variables (Kozlowski and Warner, 2017) and overall evidence for a causal gateway effect that could have a major effect on public health is unconvincing (Kozlowski and Abrams, 2016, Kozlowski and Warner, 2017, Saddleson et al., 2015). Evidence arising from secular trends in cigarette and e-cigarette use does not support that there is a gateway effect (Kozlowski and Warner, 2017). The multivariable models support that levels of satisfaction relative to cigarettes are a predictor of frequency of use of e-cigarettes.

4.2. Perceived danger from e-cigarettes

About half of the public considers that vaping is as dangerous as smoking cigarettes (Kiviniemi and Kozlowski, 2015, Kozlowski and Abrams, 2016, Kozlowski and Sweanor, 2016) and this misperception appears to be increasing (Majeed et al., 2016). Although it is clear that vaping products are not without risk, it is also clear that they are overall much less dangerous than cigarettes (Royal College of Physicians, 2016). The current findings suggest that mistaken perceptions of risk may be influencing the use of vape as a substitute for smoking, and that greater awareness of the reduced risk might promote switching to e-cigarettes.

4.3. Satisfaction is important for any recreational drug product and should be assessed

It is notable that the major Food and Drug Administration sponsored multi-million dollar PATH survey when assessing reason for use of e-cigarettes did not include any measures of satisfaction or enjoyment (Hyland et al., 2016). Enjoyment or satisfaction for a recreational drug product is likely to influence the use of the product (Kozlowski et al., 1989a, Saddleson et al., 2016). Satisfaction is considered associated with the abuse potential of drug products, and some authorities have proposed that less harmful nicotine/tobacco products should strive for only moderate levels of satisfaction (Niaura, 2016). A temporary smoking-cessation aid might be used if it offered low to moderate satisfaction. But, to compete with or replace cigarettes as a recreational drug product high levels of satisfaction are likely very important. The actual degree to which health harms are still caused by satisfying, less harmful products (in comparison to cigarettes) should be important in determining the disadvantages of the development highly satisfying alternatives to cigarettes.

5. Limitations

This is a study of predictors (correlates) of usage in self-selected users of e-cigarettes. The small sample size, especially of daily users, of e-cigarettes is a limitation. The sample is not necessarily representative of adults in the United States. No measures of nicotine usage or flavorings were included. Detailed smoking histories were not available, so adjustments for heaviness of smoking (when still smoking and if currently smoking) were not available.

6. Conclusion

This study found that frequency of use of e-cigarettes (vape) was directly associated with perceived satisfaction and indirectly associated with perceived danger, both measured in comparison to cigarettes. In addition, non-Cig-alike vaping products were more likely to be used by more frequent users. The majority of Daily users of e-cigarettes found them to be “much more satisfying” than cigarettes and less dangerous than cigarettes. Future studies need to employ measures of satisfaction and perceived harmfulness, and type of product used in order to assess the use of vaping.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Mary Bennett and Jennifer Garcia-Cano for assistance in scoring the type of product used. This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health [R01DA034072] to GGH. Please direct all correspondence to L. Kozlowski, lk22@buffalo.edu. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Lynn T. Kozlowski, Email: lk22@buffalo.edu.

D. Lynn Homish, Email: dlhomish@buffalo.edu.

Gregory G. Homish, Email: ghomish@buffalo.edu.

References

- Barrington-Trimis J.L., Urman R., Berhane K. E-cigarettes and future cigarette use. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):1–10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell K., Keane H. All gates lead to smoking: the ‘gateway theory’, e-cigarettes and the remaking of nicotine. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014;119:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz N.L., Donny E.C., Hatsukami D.K. Reduced nicotine content cigarettes, e-cigarettes and the cigarette end game. Addiction. 2017;112(1):6–7. doi: 10.1111/add.13534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farsalinos K.E., Spyrou A., Tsimopoulou K., Stefopoulos C., Romagna G., Voudris V. Nicotine absorption from electronic cigarette use: comparison between first and new-generation devices. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4133. doi: 10.1038/srep04133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heavey S.C., Homish D.L., Goodell E.A., Homish G.G. U.S. reserve soldiers' combat exposure and intimate partner violence: Not more common but it is more violent. Stress. Health. 2017 doi: 10.1002/smi.2748. 10.1002/smi.2748 (Epub: 2017/02/15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A., Ambrose B.K., Conway K.P. Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study. Tob. Control. 2016 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiviniemi M.T., Kozlowski L.T. Deficiencies in public understanding about tobacco harm reduction: results from a United States national survey. Harm Reduct. J. 2015;12:21. doi: 10.1186/s12954-015-0055-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski L.T., Abrams D.B. Obsolete tobacco control themes can be hazardous to public health: the need for updating views on absolute product risks and harm reduction. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:432. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3079-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski L.T., Sweanor D. Withholding differential risk information on legal consumer nicotine/tobacco products: the public health ethics of health information quarantines. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2016;32:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski L.T., Warner K.E. 2017. Adolescents and E-cigarettes: Objects of Concern May Appear Larger Than They Are Drug Alcohol Depend. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski L.T., Heatherton T.F., Frecker R.C., Nolte H.E. Self-selected blocking of vents on low-yield cigarettes. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1989;33(4):815–819. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski L.T., Wilkinson D.A., Skinner W., Kent C., Franklin T., Pope M. Comparing tobacco cigarette dependence with other drug dependencies: greater or equal ‘difficulty quitting’ and ‘urges to use, ‘but less’ pleasure’ from cigarettes. JAMA. 1989;261:898–901. doi: 10.1001/jama.261.6.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski L.T., Goldberg M.E., Yost B.A. Measuring smokers' perceptions of the health risks from smoking light cigarettes. Am. J. Public Health. 2000;90:1318–1319. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1318. (PMCID: PMC1446327) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeed B.A., Weaver S.R., Gregory K.R. Changing perceptions of harm of e-cigarettes among U.S. adults, 2012–2015. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill A., Brose L.S., Calder R., Hitchman S.C., Hajek P., McRobbie H. Public Health England; 2015. E-cigarettes: An Evidence Update.https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/457102/Ecigarettes_an_evidence_update_A_report_commissioned_by_Public_Health_England_FINAL.pdf (Accessed February 20, 2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech R.A., O'Malley P.M., Johnston L.D., Patrick M.E. E-cigarettes and the drug use patterns of adolescents. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016;18:654–659. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaura R.S. Truth Initiative; Washington, DC: 2016. Re-thinking Nicotine and Its Effects.http://truthinitiative.org/sites/default/files/ReThinking-Nicotine.pdf (Accessed February 20, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- Nutt D.J., Phillips L.D., Balfour D. Estimating the harms of nicotine-containing products using the MCDA approach. Eur. Addict. Res. 2014;20:218–225. doi: 10.1159/000360220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt S.I., Sargent J., Daniels L., Santos M.M., Brunette M. Appeal of electronic cigarettes in smokers with serious mental illness. Addict. Behav. 2016;59:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Physicians . RCP; London: 2016. Nicotine Without Smoke: Tobacco Harm Reduction.https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/nicotine-without-smoke-tobacco-harm-reduction-0 (Accessed February 20, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- Saddleson M.L., Kozlowski L.T., Giovino G.A. Risky behaviors, e-cigarette use and susceptibility of use among college students. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;149:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saddleson M.L., Kozlowski L.T., Giovino G.A. Enjoyment and other reasons for electronic cigarette use: results from college students in New York. Addict. Behav. 2016;54:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh T., Arrazola R.A., Corey C.G. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2016;65:361–367. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6514a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan A.S., Lee C.J., Bigman C.A. Comparison of beliefs about e-cigarettes' harms and benefits among never users and ever users of e-cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;158:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulkifli A., Abidin E.Z., Abidin N.Z. Electronic cigarettes: a systematic review of available studies on health risk assessment. Rev. Environ. Health. 2016 doi: 10.1515/reveh-2015-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]