Short abstract

WHO's “3 by 5” initiative to increase access to antiretroviral drugs to people with AIDS in developing countries is highly ambitious. Some of the biggest obstacles relate to delivering care

Access to good quality antiretroviral treatment has transformed the prognosis for people with AIDS in the developed world. Although it is feasible and desirable to deliver antiretroviral drugs in resource poor settings,1 w1 w2 few of the 95% of people with HIV and AIDS who live in developing countries receive them. The World Health Organization has launched a programme to deliver antiretroviral drugs to three million people with AIDS in the developing world by 2005, the “3 by 5” initiative.2 w3 We identify some of the challenges faced by the initiative, focusing on delivery of care.

Continuum of care

Ideally, care for people with AIDS should start with voluntary counselling and HIV testing. However, only 10% of people who need testing in low and middle income countries have access to services, and therefore most are unaware of their serological status.w5 Care should include psychological, social, and economic support as well as broad based medical care incorporating nutritional advice, prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections, and palliative care.3 w6 In many countries, this continuum remains to be set up.

The 3 by 5 initiative considers access to antiretroviral drugs as an opportunity to improve care and enhance prevention efforts.4 However, the focus on antiretroviral drugs risks distracting resources and attention from a broader model of health care. A recent survey of palliative care for people with AIDS in developing countries showed that services were often inadequate.5 Pain management was especially poor. India's decision to rapidly provide free antiretroviral drugs to 100 000 people with AIDS in the six states with the highest HIV prevalence created considerable debate, partly for this reason.6,7

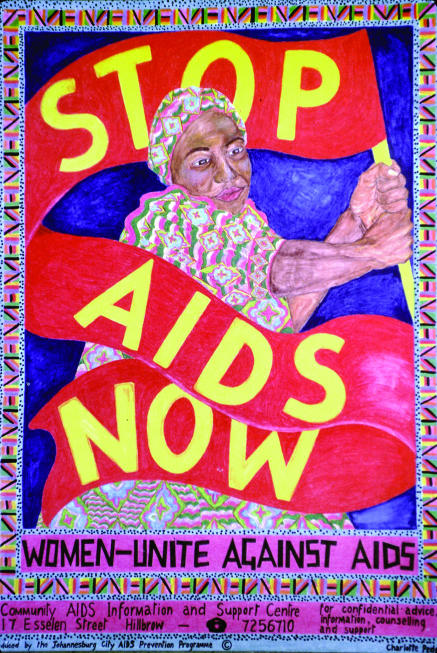

Figure 1.

Credit: FRIEDRICH STARK/STILL PICTURES

Countries need to take the opportunities presented by the WHO initiative to improve their public health infrastructure. Care for patients who do not require antiretroviral drugs is based on regular clinical follow up. But this kind of care, related to a chronic disease model, is far from the acute disease model presently dominant in the healthcare services of developing countries.8 Setting up this new model requires equipment, human resources, data management, and the use of communication tools that are both efficient and protect confidentiality.

Stigma and discrimination

The issue of confidentiality is crucially important in view of widespread AIDS related stigma and discrimination. According to UNAIDS, AIDS related stigma is “the process of devaluation of people living with or associated with HIV/AIDS.”w7 Despite more than 20 years of awareness of AIDS, the stigmatisation of people living with HIV remains strong, albeit manifested in more sophisticated ways.9

WHO asserts that access to antiretroviral drugs will rapidly reduce stigma,2 and this is true at a global level and, to an extent, at individual level. The disappearance of “body marks” such as slimness or Kaposi's sarcoma is felt as a real relief.w8 Once HIV is perceived as a chronic but treatable condition, one of the factors that amplify stigma—fear of contagion and inevitable death—is lessened. However, stigma is much more than fear of contagion. It is also a tool used by cultures to exclude those felt to have broken extant rules. The dominant stereotype of people living with HIV is a stigmatising one that casts them as immoral,10 leading to what Goffman suggests is a spoilt identity.11 In our view, the downgrading of HIV to a manageable disease is unlikely to change this perception of HIV as effectively as WHO suggests.

Antiretroviral drugs may also be stigmatising. Patients taking antiretroviral drugs in Senegal often hide their medicines. Although most of their families are supportive, some relatives still reject them. Neighbourhood or professional relationships still convey a danger of rejection, especially in contexts of conflict or competition.w9

Recent research suggests that use of testing services and disclosure of status is constrained because of “anticipated and actual stigma experienced by people living with HIV.”w10 In tandem with the development of AIDS care and support for health workers, the 3 by 5 initiative should promote training programmes for healthcare workers on medical ethics and human rights. Since antenatal clinics, sexual health services, and tuberculosis treatment centres have been suggested as entry points for AIDS care, it is important that the stigmatising effect of AIDS does not deter users of these services.12

Systems of delivery

Although the 3 by 5 initiative has already brought some important technical advances, such as the development of simplified treatment regimens and monitoring protocols,13 some issues related to the delivery of antiretroviral drugs remain. Some experts have argued that the best way to deliver highly active antiretroviral drugs treatment (HAART) is likely to be through directly observed therapy (DOT), so called DOTHAART,w11 in order to support adherence.

Lessons need to be learnt from the use of DOTs in tuberculosis.14 Although most developing countries have adopted DOTs for tuberculosis, and some have seen apparent successes,15 not all randomised controlled trials show that DOTs confer benefit.w12 w13 Experience in Africa has been highly variable.16 Treatment completion rates vary from 37% (low) in the Central African Republic to 78% (moderate) in Kenya and Tanzania. Clearly multiple approaches to delivering antiretroviral drugs will be required to close such gaps.

Senegal, Malawi, and South Africa have achieved high and sustainable adherence rates for antiretroviral drugs without directly observed treatment.17 w4 The important factors seem to be the regular supply of medicines, efficient health service management, and support through “antiretroviral drugs literacy promotion” and self support groups.

As the quality of life for patients on antiretroviral drugs improves, frequent contact with healthcare providers may be difficult. In Dakar, missing monthly appointments to obtain antiretroviral drugs was the first reason for non-compliance among patients in their second year of treatment.w14 Most patients had returned to their jobs, often requiring stays far from home, especially for sailors and retailers. A visit to the hospital to obtain antiretroviral drugs often takes several hours, which is inconvenient for all patients.

Community involvement

Delivering antiretroviral drugs to three million people in developing countries by 2005 will require huge increases in trained staff; an estimated 100 000 trained health providers and treatment supporters will be required by the end of 2005.w15 The initiative plans to involve community based organisations and include people with AIDS at all levels. Administering such a workforce risks diverting scarce healthcare managers from already overloaded essential programmes.

Community based organisations are very heterogeneous. In countries such as Burundi they have set up whole AIDS care programmes, whereas in other countries their role is more limited, perhaps relating only to communication of prevention messages. Healthcare workers may find it difficult to accept such organisations as partners, especially if they have promoted traditional medicines for AIDS or faith healing.w16 w17 An evaluation in Burkina Faso has shown that although community based organisations are thought to be more accessible, more supportive, and more able to guarantee follow up than healthcare services, they have poor results because of losing patients.w18 Internal power distribution within the organisations may mean that people in greatest need of treatment are not the ones who get first access to antiretroviral drugs, and this can result in disaffection among potential users. Training may be insufficient to change the social strategies and issues of established community organisations, healers, or groups. Defining criteria to select possible partners will be a hard task.

Access to treatment

Concern has been voiced that existing criteria for access are inequitable.18 Presently most programmes providing treatment do so at different tariffs based on different ways of considering equity. A patient who gets free treatment in one programme might be asked for a payment in excess of average monthly wages in a neighbouring programme. Providing free or subsidised treatment on a first come, first served basis tends to favour richer, urban, and more educated people. Perversely, these are the people in whom treatment might be least effective as many of them will have previously purchased antiretroviral drugs through private facilities. Leaving decisions about charges to front line staff leads to inconsistencies and may lead to corruption.

Criteria for access to subsidised antiretroviral drugs in national programmes differ substantially between countries. In West Africa, these criteria are based on social characteristics, level of income, profession, social status, and number of dependants.w19 Perceptions of equity differ at local levels, often related to a community's social dynamics. Such variation is difficult to manage from both a public health and a clinical perspective and doesn't fulfil requirements for equity at national or international levels.

Introducing user charges is likely to be inequitable as well as adversely affecting adherence.18,19 Many families will already be living in poverty as a result of a reduction in income or paying for AIDS care. Providing free access to antiretroviral drugs based on rights and not ability to pay,19 as occurs in the Senegal national programme, will be most equitable, will resolve dilemmas over the treatment of migrants, and will also reduce migration to obtain antiretroviral drugs.

Conclusions

The 3 by 5 initiative faces important challenges in meeting the desperate need for antiretroviral drugs in many developing countries,. Constructive dialogue between stakeholders with different agendas, including healthcare workers, public health managers, community and faith based organisations, and people with AIDS, will be crucial if the initiative is to succeed. The prevailing social strategies must be considered carefully when setting up programmes and working relationships, in order to capitalise on and not undermine the existing social order. In an interview in Bangkok, the executive director of UNAIDS noted that “antiretroviral therapy is still a rare commodity, and it will be for some time. The result of that is always higher price, and also higher price in terms of power. Who has access to it, and who comes first: it's a terrible issue.”w20 Without addressing this and the other issues we have raised, the 3 by 5 initiative may fall short of its goals.

Summary points

The 3 by 5 initiative aims to deliver antiretroviral drugs to three million people with HIV infection in developing countries by 2005

To succeed, the initiative must develop a chronic disease model of care through a strengthened public health infrastructure

Cooperation is needed with existing essential programmes to manage scarce health staff

The influence of stigma requires monitoring

Access to treatment must be based on rights and not ability to pay

Supplementary Material

References w1-w20 are on bmj.com

References w1-w20 are on bmj.com

ASF, IJH, and DSM have received support from Health and Development Networks (www.hdnet.org) to report on international AIDS events which have helped inform this article. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of organisations for which the authors work. We thank the external reviewers for their helpful comments.

Contributors and sources: This article was written after discussion between the authors at recent international AIDS conferences in the light of keynote presentations by WHO/UNAIDS. The authors have experience of working in AIDS programmes in Asia and Africa both in government and non-government sectors. ASF wrote the first draft and is the guarantor. IJH, AD, and DSM all revised and added to parts of the paper.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Mukherjee JS, Farmer PE, Niyizonkiza D, McCorkle L, Vanderwarker C, Teixeira P, et al. Tackling HIV in resource poor countries. BMJ 2003;327: 1104-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Word Health Organization. Treating 3 million by 2005: making it happen. Geneva: WHO, 2003. www.who.int/3by5/en/ (accessed 15 Dec 03).

- 3.Osborne CM, van Praag E, Jackson H. Models of care for patients with HIV/AIDS. AIDS 1997;11B: 135-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gayle H, Lange JM. Seizing the opportunity to capitalise on growing access to HIV treatment to expand HIV prevention. Lancet 2004;364: 6-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harding R, Stewart K, Marconi K, O'Neill JF, Higginson IJ. Current HIV/AIDS end-of-life care in sub-Saharan Africa: a survey of models, services, challenges and priorities. BMC Public Health 2003;3: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar S. India's treatment programme for AIDS is premature. BMJ 2004;328: 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma DC. India unprepared for antiretroviral treatment plan. Lancet 2003;362: 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitahata MM, Tegger MK, Wagner EH, Holmes KK. Comprehensive health care for people infected with HIV in developing countries. BMJ 2002;325: 954-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med 2003;57: 13-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanley LD. Transforming AIDS: the moral management of stigmatized identity. Anthropol Med 1999;6: 103-20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1963.

- 12.Holmes W. 3 by 5, but at what cost? Lancet 2004;363: 1072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Scaling up antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited setting: treatment guidelines for a public health approach. Geneva: WHO, 2003.

- 14.Gupta R, Irwin A, Raviglione MC, Kim JY. Scaling-up treatment for HIV/AIDS: lessons learned from multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Lancet 2004;363: 320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.China Tuberculosis Control Collaboration. The effect of tuberculosis control in China. Lancet 2004;364: 417-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens W, Kaye S, Corrah T. Antiretroviral therapy in Africa. BMJ 2004;328: 280-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanièce I, Ciss M, Desclaux A, Diop K, Mbodj F, Ndiaye B, et al. Adherence to HAART and its principal determinants in a cohort of Senegalese adults. AIDS 2003;7(suppl 3): S103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loewenson R, McCoy D. Access to antiretroviral treatment in Africa. BMJ 2004;328: 241-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukherjee J. Basing treatment on rights rather than ability to pay: 3 by 5. Lancet 2004;363: 1071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.