Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) identified diverse clinically relevant genomic alterations in pediatric, adolescent, and young adult patients with thyroid carcinoma, including 83% (34/41) of papillary thyroid carcinoma cases harboring activating kinase mutations or activating kinase rearrangements. These genomic observations and index cases exhibiting clinical benefit from targeted therapy suggest that young patients with advanced thyroid carcinoma can benefit from CGP and rationally matched targeted therapy.

Keywords: Comprehensive genomic profiling, Genomics, Oncogene proteins, Fusion, Molecular targeted therapy, Thyroid carcinoma, Vandetanib

Abstract

Background.

Thyroid carcinoma, which is rare in pediatric patients (age 0–18 years) but more common in adolescent and young adult (AYA) patients (age 15–39 years), carries the potential for morbidity and mortality.

Methods.

Hybrid‐capture‐based comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) was performed prospectively on 512 consecutively submitted thyroid carcinomas, including 58 from pediatric and AYA (PAYA) patients, to identify genomic alterations (GAs), including base substitutions, insertions/deletions, copy number alterations, and rearrangements. This PAYA data series includes 41 patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), 3 with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC), and 14 with medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC).

Results.

GAs were detected in 93% (54/58) of PAYA cases, with a mean of 1.4 GAs per case. In addition to BRAF V600E mutations, detected in 46% (19/41) of PAYA PTC cases and in 1 of 3 AYA ATC cases, oncogenic fusions involving RET, NTRK1, NTRK3, and ALK were detected in 37% (15/41) of PAYA PTC and 33% (1/3) of AYA ATC cases. Ninety‐three percent (13/14) of MTC patients harbored RET alterations, including 3 novel insertions/deletions in exons 6 and 11. Two of these MTC patients with novel alterations in RET experienced clinical benefit from vandetanib treatment.

Conclusion.

CGP identified diverse clinically relevant GAs in PAYA patients with thyroid carcinoma, including 83% (34/41) of PTC cases harboring activating kinase mutations or activating kinase rearrangements. These genomic observations and index cases exhibiting clinical benefit from targeted therapy suggest that young patients with advanced thyroid carcinoma can benefit from CGP and rationally matched targeted therapy.

Implications for Practice.

The detection of diverse clinically relevant genomic alterations in the majority of pediatric, adolescent, and young adult patients with thyroid carcinoma in this study suggests that comprehensive genomic profiling may be beneficial for young patients with papillary, anaplastic, or medullary thyroid carcinoma, particularly for advanced or refractory cases for which clinical trials involving molecularly targeted therapies may be appropriate.

Introduction

While rare in patients 0 to 14 years of age (0.1–0.8 cases per 100,000 individuals), thyroid carcinoma is more common in adolescents and young adults (AYA; 15–39 years of age); in the United States, the incidence rate of differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC) is increasing in this combined pediatric and AYA (PAYA) population [1]. The clinicopathologic characteristics of young patients with DTC seem to differ from those of adults with DTC, as pediatric patients often present with more advanced and aggressive features than adults [2], [3], [4]. Among pediatric patients with thyroid carcinoma, multivariate analysis has identified nonpapillary histology, male gender, metastasis, and lack of surgery as independent negative prognostic factors [4]. In spite of this, outcomes for PAYA patients with thyroid carcinoma are generally excellent [2], [5]. However, the risk for second primary malignancies is significantly higher in patients who have received radiation therapy for DTC, and these second primary malignancies contribute to increased overall mortality in these patients [6], [7].

In addition to the American Thyroid Association guidelines for the management of differentiated thyroid nodules, which are primarily focused on adult patients and include recommendations for extensive surgery and radioactive iodine (RAI) treatment, a distinct set of guidelines for the management of pediatric patients has been published in an effort to mitigate the long‐term negative effects of aggressive surgery and RAI treatment in young patients [3], [8]. In certain cases of advanced disease in young patients for whom standard of care is not possible, a strategy that matches molecularly targeted therapy to tumors harboring clinically relevant genomic alterations (CRGAs)—defined here as genomic alterations (GAs) that, on the basis of clinical and preclinical evidence, may confer sensitivity to approved targeted therapies or investigational therapies being evaluated in clinical trials—may be appropriate.

Given the evolving medical practices for effectively managing pediatric and young adult patients with advanced, relapsed/refractory thyroid carcinoma, we assessed 58 cases of PAYA papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC), and medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) with comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) in the course of clinical care to identify CRGAs that could suggest benefit from targeted therapy.

Materials and Methods

CGP was performed in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments‐certified, College of American Pathologists‐accredited, New York State‐regulated reference laboratory (Foundation Medicine Inc., Cambridge, MA). At least 50 ng of DNA per specimen was extracted from 512 clinical formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded, consecutively submitted thyroid carcinoma specimens from the primary tumor or a metastatic lesion; next‐generation sequencing was performed on hybridization‐captured, adaptor ligation‐based libraries to high, uniform coverage (>500 times) for all coding exons of at least 236 cancer‐related genes plus 14 or 19 genes frequently rearranged in cancer.

Base substitutions, short insertions/deletions (indels), focal gene amplifications, homozygous deletions, and select rearrangements were determined and reported for each patient sample. Approval for this study, including a waiver of informed consent and a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act waiver of authorization, was obtained from the Western Institutional Review Board (protocol no. 20152817).

Results

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling of Tumors from Patients with Papillary, Anaplastic, and Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma

Tumors from 512 patients with thyroid carcinoma, including 303 cases of PTC, 132 cases of ATC, and 77 cases of MTC, were assayed with CGP in the course of clinical care. CGP identified at least one GA in 99% (505/512) of cases. A mean of 2.9 GAs was detected per patient (median of 2; range, 0–12), and the mean number of GAs was low across PTC, ATC, and MTC (2.5, 4.5, and 1.8, respectively). This series of patients was 51% (262/512) female and included individuals ranging from 7 to 96 years of age, at the time of molecular testing, with a median age of 60 years. Eighty‐one percent of the GAs detected were short nucleotide variants (SNVs); 14% were copy number alterations (CNAs), either focal amplifications or deletions; and 5% were genomic rearrangements, including gene fusions (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Alteration classes detected by comprehensive genomic profiling of patients with thyroid carcinoma. (A): A total of 1,478 GAs were detected in 512 patients with thyroid carcinoma. (B): Percentage of alteration classes detected among 753 GAs in patients with PTC, 583 GAs in patients with ATC, and 142 GAs in patients with MTC. (C): Percentage of alteration classes detected among 54 GAs in patients younger than 40 years of age at the time of biopsy with PTC, 8 GAs in patients younger than 40 years of age at the time of biopsy with ATC, and 19 GAs in patients younger than 40 years of age at the time of biopsy with MTC. SNVs (blue) are more common in younger patients. Abbreviations: ATC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; AYA, adolescent and young adult; GA, genomic alterations; MTC, medullary thyroid carcinoma; PAYA, pediatric, adolescent, and young adult; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; SNV, single nucleotide variants.

SNVs were the most common type of alteration in PTC (85%), ATC (77%), and MTC (80%) (Fig. 1). Whereas CNAs represented 19%–20% of the alterations detected in ATC and MTC, they represented only 8% of alterations detected in PTC (Fig. 1). Genomic rearrangements, including oncogenic fusions, represented 7% of the detected GAs in PTC, whereas they represented only 4% of GAs in ATC and were not detected in any of the MTC cases (Fig. 1).

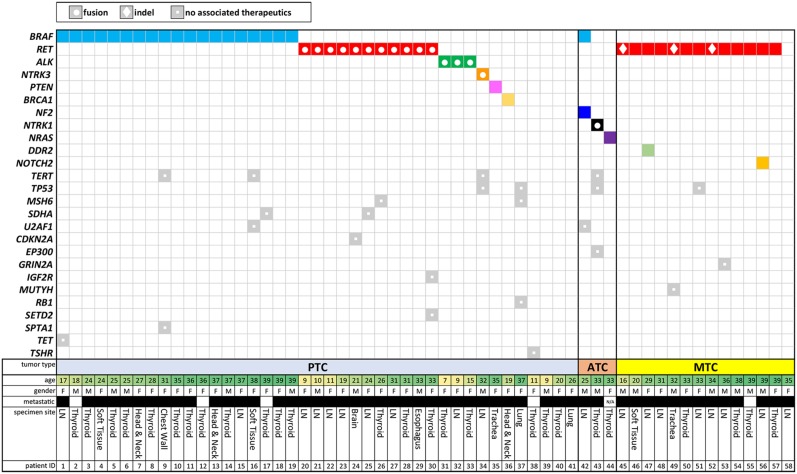

Among these 512 patients, 58 were under 40 years of age at the time of biopsy for molecular testing (41 PTC, 3 ATC, and 15 MTC cases) (Fig. 2). Furthermore, this cohort included 11 pediatric patients (18 years or younger), most of whom of whom had PTC (10/11 [91%]) (Fig. 2). One adolescent patient (16 years of age) had MTC, and none of the pediatric cases had ATC (Fig. 2). The PAYA cases were predominantly advanced, with 91% of cases featuring local or distant metastasis (Fig. 2). Collectively, these 58 PAYA cases featured SNVs and rearrangements but lacked the CNAs (both amplifications and homozygous deletions) observed in patients 40 years of age and older (Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

Tile plot of genomic alterations identified in patients under the age of 40 years at the time of comprehensive genomic profiling. A total of 58 pediatric, adolescent, and young adult patients, including 41 with PTC, 3 with ATC, and 15 with MTC. Additional details shown include age at time of sample collection, gender, metastatic disease (black box), and specimen site. Abbreviations: ATC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; F, female; LN, lymph node; M, male; MTC, medullary thyroid carcinoma; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Genomic Alterations Detected in Papillary Thyroid Carcinomas From PAYA Patients

While 70% (213/303) of all PTC cases harbored alterations of BRAF, predominantly V600E (92%), BRAF mutation was detected in only 46% (19/41) of PAYA PTC cases and was largely constrained to the older portion of this subgroup—no BRAF mutations were detected in patients younger than 17 years of age (0%; 0/8) (supplemental online Fig. 1; Fig. 2). Despite the reduced frequency of BRAF mutations in PAYA PTC cases, an activating kinase mutation or a kinase fusion was identified in 83% (34/41) of these cases. Of the 7 cases lacking kinase alterations, 3 harbored mutations in tumor suppressor genes (PTEN, BRCA1, and MSH6). In contrast to the full cohort of patients with PTC, in which rearrangements of oncogenes, including RET, BRAF, ALK, NTRK1, NTRK3, and FGFR2, were detected in 15% (45/303) of cases, these oncogenic fusions were detected in 37% (15/41) of PAYA PTC cases (Figs. 2, 3). The frequency of oncogenic fusions was further enriched in pediatric PTC patients; 60% (6/10) of pediatric PTCs harbored an RET or ALK fusion (Fig. 2). Local or distant metastasis was observed in each of the 15 PAYA PTC cases harboring an oncogenic fusion, whereas the tumor was reported to be localized in several (3/19 [16%]) of the PAYA patients harboring BRAF V600E (Fig. 2). When detected in PAYA patients with PTC, oncogenic fusions were the sole CRGA. Similarly, in the 19 PAYA PTC cases harboring BRAF V600E, no other CRGAs were detected and only 4 cases exhibited co‐occurring GAs (21%) (TET2, TERT, SDHA, U2AF1, and SPTA1).

Figure 3.

Distribution of oncogenic fusions detected by CGP in papillary and anaplastic thyroid carcinomas. Distribution of (A) 303 patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma ranging from 7 to 96 years of age and (B) 132 patients with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma ranging from 25 to 86 years of age at the time of sample collection. Patients harboring oncogenic fusions are highlighted. Abbreviation: CGP, comprehensive genomic profiling.

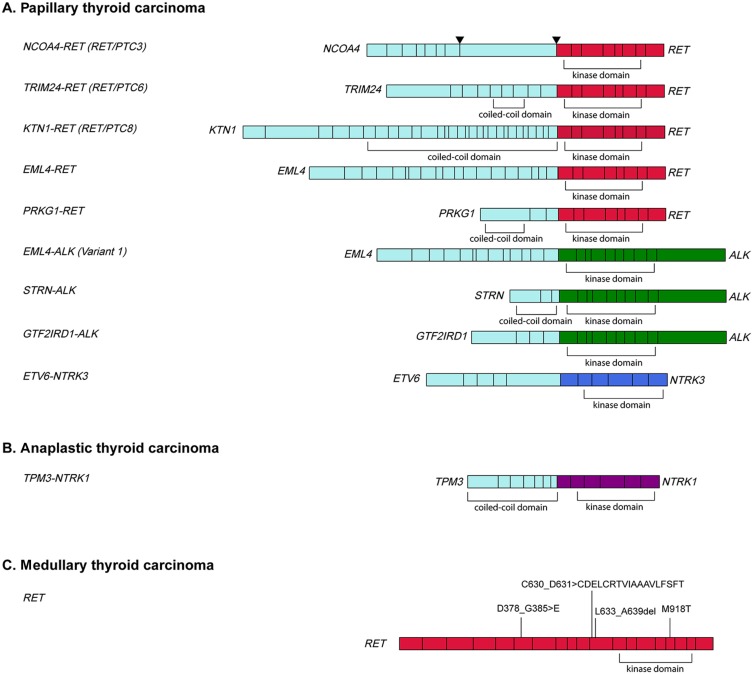

The frequency of both RET and ALK fusions in young patients exceeded that in patients older than 39 years of age. RET fusions were detected in 27% (11/41) of PAYA PTC cases compared with 7% (19/262) of patients older than age 39 years. Seven of the 11 RET fusions were NCOA4‐RET (RET/PTC3), and the other 4 consisted of TRIM24‐RET (RET/PTC6), KTN1‐RET (RET/PTC8), PRKG1‐RET, and EML4‐RET (Fig. 4, supplemental Online Fig. 1). Similarly, fusions involving ALK, specifically EML4‐ALK, STRN‐ALK, and GTF2IRD1‐ALK, were detected in 7% (3/41) of PAYA PTC cases compared with less than 1% (2/262) of patients older than 39 years of age (Figs. 3, 4). An ETV6‐NTRK3 fusion was detected in 1 PAYA patient with PTC (2%) but not in any PTC patients older than age 39 years (Figs. 3, 4). Whereas rearrangements involving BRAF were detected in 4% (11/262) of patients older than 39 years of age, they were not detected in PAYA patients (Figs. 2, 3).

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of fusions detected in pediatric, adolescent, and young adult (PAYA) patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) or anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) and RET mutations in PAYA patients with medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC). (A): Oncogenic RET (11/41), ALK (3/41) and NTRK3 (1/41) kinase fusions identified by comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) in PAYA patients with PTC. NCOA4‐RET fusions were detected in 7 cases, whereas the other fusions were detected in single cases. Breakpoints were detected in both intron 7 and exon 8 of NCOA4. (B): A TPM3‐NTRK1 fusion was identified by CGP in 1 of 3 AYA patients with ATC. (C): RET missense mutations and indels were identified by CGP in 13 of 14 PAYA patients with MTC. Ten cases harbored RET M918T, whereas indels were detected in exons 6 or 11 in 3 cases.

Genomic Alterations Detected in Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinomas From PAYA Patients

In the 3 PAYA ATC cases, we identified a TPM3‐NTRK1 fusion, an NRAS mutation, and BRAF V600E co‐occurring with an NF2 mutation (Fig. 2). The NTRK1 fusion was detected in a 33‐year‐old patient with ATC and co‐occurred with TP53 and TERT mutations. Whereas TP53 and TERT mutations were common among ATC cases of any age, detected in 80% (105/132) and 53% (52/98) of the cases analyzed for mutations in these genes, kinase fusions (NTRK1, RET, BRAF) were rare among the full cohort of ATC patients, detected in only 4% (5/132) of cases (Fig. 3, supplemental online Fig. 1).

Genomic Alterations Detected in Medullary Thyroid Carcinomas From PAYA Patients

RET mutations were detected in 93% (13/14) of PAYA MTC cases, predominantly M918T, which was found in 71% (10/14) of cases (Fig. 2). The remaining 3 RET mutations were novel indels in exon 11 (RET C630_D631>CDELCRTVIAAAVLFSFT and RET L633_A639del) and exon 6 (RET D378_G385>E) (Figs. 2, 3).

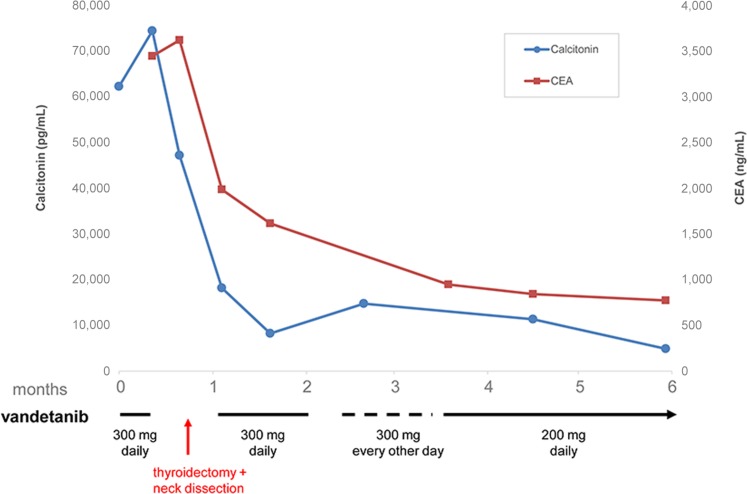

Clinical Benefit From Vandetanib in PAYA Patients With Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma Harboring Noncanonical RET Mutations

Clinical outcomes were available for two PAYA MTC patients with novel RET indels, both of whom received clinical benefit from vandetanib treatment. A 16‐year‐old adolescent with Hirschsprung disease and MTC (patient 45 in Fig. 2) harboring an in‐frame aberration in the cadherin‐like domain of the RET extracellular domain (ECD) (RET D378_G385>E) was treated with vandetanib alone. This patient presented with a primary tumor in the right thyroid and extensive nodal disease and multiple lung, liver, and bone metastases. The patient received vandetanib for 1 week and then had removal of the primary tumor and neck dissection. He resumed vandetanib within 4 days after surgery. This patient continues to have an ongoing biochemical response lasting more than 6 months, as manifested by continuing decline in both calcitonin (from 74,412 pg/mL to 4,874 pg/mL) and carcinoembryonic antigen (from 3,619 ng/mL to 771 ng/mL) (Fig. 5) with corrected QT interval (QTc) of 434 milliseconds. Vandetanib side effects in this patient have included drug‐related acne that requires topical treatment, diarrhea that was not dose‐limiting, and alterations to QTc that required a dose modification (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Clinical response to vandetanib in a 16‐year‐old with both long‐standing Hirschsprung disease and metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma (mediastinum, lungs, liver, bone) whose tumor harbors an indel within RET exon 6 (D378_G385>E). Abbreviation: CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

Additionally, a 34‐year‐old man whose tumor harbors RET L633_A639del (patient 52 in Fig. 2) began treatment with vandetanib for progressive lymph node and pulmonary metastasis and experienced disease stabilization, as determined by reduced calcitonin rise and stable tumor volume, for over 6 months; however, vandetanib treatment was stopped after 7 months when disease progression was noted by both increased calcitonin levels and tumor volume. While the patient was receiving treatment with vandetanib, dose reduction was required because of moderate toxicity resulting from vandetanib treatment.

Discussion

Using CGP conducted during the course of clinical care, this study focused on PAYA cases of papillary, anaplastic, and medullary thyroid carcinoma originating from a variety of practice settings and identified GAs in 93% of these patients. Moreover, most (90%) of the PAYA patients analyzed harbored CRGAs, alterations for which substantial clinical evidence supports an association with response to targeted therapies in various solid tumors, including thyroid carcinomas [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16].

Consistent with previous retrospective studies [17], [18], we recognized a relative paucity of BRAF V600E mutations in our series of PAYA PTC cases compared with the full cohort of patients of any age (46% vs. 70%) and identified a higher percentage of oncogenic fusions in the younger subpopulation (37% vs. 15%). Among PAYA patients with PTC, oncogenic BRAF mutations and kinase fusions were detected in 86% of cases. BRAF mutation was not detected in young pediatric patients in our series, suggesting that PTC may be driven by alternative mechanisms in these patients.

Beyond mutations in MAPK pathway genes (BRAF and NRAS), oncogenic kinase fusions were identified in 37% of PAYA PTCs and in 1 of 3 AYA ATCs, whereas RET mutations were detected in 93% of PAYA MTCs. Thyroid carcinoma is notable among cancers due to the high frequency of recurrent fusions involving kinases [19]. Among thyroid carcinomas, oncogenic fusions are most frequently found in PTCs [20], whereas they are rare in ATC [21], and, with a notable exception of a RET fusion identified in a patient with MTC, largely absent in MTC [22], [23].

Several studies have genomically characterized pediatric thyroid carcinomas, most frequently in the context of radiation exposure [17], [18], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30]. Genomic rearrangements have been reported to be more prevalent in pediatric patients with radiation‐induced PTC than in pediatric patients with sporadic PTC [28], [30]. However, high frequencies of fusions have also been appreciated in sporadic cases [17].

In this study, we identified PAYA patients harboring RET, NTRK1, NTRK3, and ALK fusions. Chimeric proteins that pair the RET, NTRK1, NTRK3, and ALK kinase domains with dimerization domains have been characterized as oncogenic drivers, identified in a variety of tumor types and shown to confer sensitivity to molecularly targeted therapies [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [31], [32], [33], [34]. RET and NTRK fusions, though initially identified in PTC as the first kinase fusions in solid tumors, have been more frequently targeted in other tumor types [35], [36], [37], [38]. ALK rearrangements, initially identified in lymphoma (NPM‐ALK) and associated with a subset of non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, have since been detected in a number of solid tumor types including PTC, poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma (PDTC), and ATC [12], [19], [21], [39], [40], [41], [42]. Oncogenic fusions provide a potential avenue for targeting tumors that harbor them, particularly in the setting they are observed in the PAYA patients in this study, in which they are the sole oncogenic driver and largely lack co‐mutations.

In total, RET rearrangements involving fusion partners with dimerization domains were detected in 11 (27%) of the 41 PAYA PTC patients. In addition to 7 cases harboring the canonical NCOA4‐RET (RET/PTC3) fusion, TRIM24‐RET (RET/PTC6), KTN1‐RET (RET/PTC8), EML4‐RET, and PRKG1‐RET fusions were also detected. Each of these fusions involves a dimerization domain that is predicted to result in constitutive activation of RET kinase. Several multikinase inhibitors with activity against RET, namely cabozantinib, vandetanib, lenvatinib, sorafenib, regorafenib, ponatinib, and sunitinib, have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in various indications, including MTC (cabozantinib and vandetanib) and RAI‐refractory DTC (lenvatinib and sorafenib).

A patient with metastatic PTC experienced durable stable disease following surgical excision of a cutaneous manifestation harboring a CCDC6‐RET fusion and vandetanib treatment [43]. Additionally, partial responses have been reported in patients with RET‐rearranged NSCLC treated with cabozantinib [13], [44], [45], [46]. Preclinical studies demonstrated that cells transformed by KIF5B‐RET are sensitive to treatment with vandetanib, sorafenib, and sunitinib [47], [48], [49].

ALK fusions were observed in 3 pediatric patients in this study. ALK rearrangements have been reported in 1.5% of PTCs and have additionally been detected in PDTC and ATC [12], [21], [41], [42]. ALK rearrangements have been largely detected in adult patients, and more frequently in those exposed to radiation; however, a STRN‐ALK fusion has been previously reported in a 13‐year‐old patient with PTC and no history of radiation exposure [41], [50].

EML4‐ALK, detected here in a 7‐year‐old patient with PTC, has been identified most frequently in NSCLC and previously reported in a 62‐year‐old patient with PTC [51]. An oncogenic STRN‐ALK fusion was detected in this study in a 15‐year‐old patient with PTC. STRN‐ALK fusions have been reported in 1.6% of well‐differentiated PTC, but also in a higher prevalence of poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma (9%) and ATC (4%), indicating that STRN–ALK fusions are significantly enriched in aggressive thyroid cancers prone to dedifferentiation [12], [52]. In this study, a GTF2IRD1‐ALK fusion was detected in a 9‐year‐old with PTC. While the GTF2IRD1‐ALK has not been functionally characterized, it has been previously reported in a 41‐year‐old patient with PTC [19].

Importantly, ALK fusions may confer sensitivity to molecularly targeted therapies, including crizotinib, ceritinib, or alectinib, which are approved by the FDA to treat ALK‐rearranged NSCLC and are in clinical trials for the treatment of other tumor types. A patient with ALK‐rearranged ATC achieved a major response to crizotinib [42] while another patient with ATC that included a PTC component and harbored a STRN‐ALK fusion responded well to crizotinib treatment [12].

The ETV6‐NTRK3 and TPM3‐NTRK1 fusions were detected in PTC and ATC cases, respectively. Clinical and preclinical data suggest that NTRK fusions may predict sensitivity to TRK inhibitors [14], [15], [16], [32], [53], [54]. While agents that more specifically inhibit TRK proteins are in clinical trials [15], [55], pediatric patients harboring NTRK1 fusions have experienced clinical benefit from treatment with crizotinib, including a durable near‐complete response [14], [32], [53].

While we did not identify fusions of ROS1 [56] or BRAF rearrangements [57] in our PAYA cases, oncogenic drivers were detected in 83% (34/41) of the PAYA PTC cases and in 100% of the 3 AYA ATC cases. Oncogenic drivers, whether they are mutations in the mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway or fusions are almost always mutually exclusive in thyroid carcinomas [59], [60]. Of the 7 PAYA PTC cases that did not harbor a BRAF mutation or fusion, mutations of tumor suppressors (PTEN, BRCA1, TP53, RB1, and MSH6) were detected in 3 cases. Although activating BRAF rearrangements have been reported in cases of pediatric thyroid carcinoma, others have noted that these rearrangements have not been detected in cohorts of sporadic thyroid carcinoma, only in data sets including cases possibly induced by ionizing radiation [2], [28].

Although less prevalent than PTC, MTC carries a worse prognosis. MTC has been reported in <5% of young patients and may be sporadic or, more commonly, associated with a germline RET mutation in the context of multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) 2A or MEN 2B [61]. Although 10‐year survival in patients with local MTC is 96%, it is 76% for regional stage disease and only 40% for patients with distant metastases at diagnosis [62]. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that age is a predictor of survival; patients diagnosed with MTC at 40 years of age or younger exhibit better prognosis than older patients [62]. In pediatric patients with MTC, 15‐year survival is 86%, and although this is improved relative to older patients with MTC, it is reduced relative to pediatric patients with PTC (97%) who also exhibit significantly increased mean survival time [4].

Genomically, most patients with classical MEN2A harbor germline mutations in RET exons 10 (C609, C611, C618, or C620) or 11 (C634), whereas sporadic MTC is predominantly driven by activating somatic RET mutations, typically RET M918T [22], [63]. In addition to RET M918T, detected in 71% of the PAYA MTC cases analyzed here, we identified 3 novel indels within the RET ECD: RET C630_D631>CDELCRTVIAAAVLFSFT, RET L633_A639del, and RET D378_G385>E.

Although functionally uncharacterized, RET C630_D631>CDELCRTVIAAAVLFSFT is an in‐frame duplication within exon 11 that is similar to a duplication reported in a family with MEN2A [64]. The patients harboring the other two RET indels detected were each treated with the RET kinase inhibitor vandetanib and exhibited stable disease. The 34‐year‐old man harboring RET L633_A639del in this study was treated with vandetanib and exhibited stable disease for 6 months before progressing with increased tumor marker levels and increased tumor volume. RET L633_A639del has not been previously reported but resembles deletions detected in this region that have been shown to promote ligand‐independent receptor dimerization and RET activation [65], [66]. Patients with MTC harboring similar indels within RET exon 11 (RET L629_D631>H or RET E632_T636del) have been treated with cabozantinib and exhibited clinical benefit [67].

RET D378_G385>E was detected in a 16‐year‐old patient with both Hirschsprung disease and MTC, suggesting that this alteration is likely germline. The co‐occurrence of Hirschsprung disease and MEN2 is rare but has been associated with a subset of RET mutations known as Janus mutations [63], [68]. The known Janus mutations are restricted to exon 10 and affect cysteine residues at C609, C611, C618, and C620 in the RET protein; these mutations were not detected in this patient. RET D378_G385>E, in exon 6, is distinct from the known Janus mutations, which occur at specific ECD cysteines, and rather resemble a functionally uncharacterized mutation (RET 379_381>F) previously reported in a patient with Hirschsprung disease [69]. While RET mutations associated with nonsyndromic Hirschsprung disease are typically appreciated to be inactivating, their mechanisms are diverse and cell‐specific [70]. This patient, who presented with extensive right thyroid and nodal disease and has multiple lung, liver, and bone metastases, is being treated with vandetanib, which was begun prior to thyroidectomy and neck dissection and continues to exhibit an ongoing biochemical response lasting >6 months.

As is the case for other targeted inhibitors of RET, vandetanib inhibits additional proteins involved in cellular proliferation and angiogenesis, including vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 and epidermal growth factor receptor; therefore, the inhibition of these other targets may not be ruled out as having an effect in the disease stabilization observed in the two patients reported here. Only 1% of patients in the phase III clinical trial that led to the approval of vandetanib for the treatment of patients with advanced MTC were identified as RET‐negative; however, subgroup analysis showed an improved objective response rate in patients positive for RET M918T relative to patients harboring other RET mutations (54.5% vs. 30.9%) [9].

Conclusion

CGP identified CRGAs in 90% of the PAYA thyroid carcinomas analyzed in this study. Moreover, 37% of PTC cases in this series harbored diverse and potentially targetable oncogenic rearrangements of RET, ALK, and NTRK3, while TPM3‐NTRK1 was detected in one of the three AYA ATC cases. Additionally, two PAYA MTC cases featuring novel RET mutations benefitted from vandetanib treatment. Although a full range of treatment options must be considered to effectively manage thyroid carcinoma in PAYA patients, these findings suggest that molecularly targeted therapies may be appropriate in the setting of progressive disease that is insensitive to RAI [3], [71]. These findings in aggregate suggest that CGP conducted during the course of clinical care may inform treatment decisions for young patients with advanced thyroid carcinoma.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mark Rosenzweig of Foundation Medicine for helpful discussions and Dan Spritz, also of Foundation Medicine, for editorial support.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Pierre Vanden Borre, Alexa B. Schrock, Kai Wang, Siraj M. Ali

Provision of study material or patients: Peter M. Anderson, John C. Morris III,

Collection and/or assembly of data: Pierre Vanden Borre, Alexa B. Schrock, Kai Wang,

Data analysis and interpretation: Pierre Vanden Borre, Andreas M. Heilmann, Oliver Holmes, Adrienne Johnson, Steven G. Waguespack, Kar‐Ming Fung, Siraj M. Ali

Manuscript writing: Pierre Vanden Borre, Alexa B. Schrock, Peter M. Anderson

Final approval of manuscript: Pierre Vanden Borre, Alexa B. Schrock, Peter M. Anderson, John C. Morris III, Andreas M. Heilmann, Oliver Holmes, Kai Wang, Adrienne Johnson, Steven G. Waguespack, Sai‐Hong Ignatius Ou, Saad Khan, Kar‐Ming Fung, Philip J. Stephens, Rachel L. Erlich, Vincent A. Miller, Jeffrey S. Ross, Siraj M. Ali.

Disclosures

Pierre Vanden Borre: Foundation Medicine Inc. (E, OI); Alexa B. Schrock: Foundation Medicine Inc. (E, OI); Andreas M. Heilmann: Foundation Medicine Inc. (E, OI); Oliver Holmes: Foundation Medicine Inc. (E, OI); Kai Wang: Foundation Medicine (E, OI); Adrienne Johnson: Foundation Medicine Inc. (E, OI); Sai‐Hong Ignatius Ou: Pfizer, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, ARIAD, Astra Zeneca (C/A); Roche/Genentech, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis (H); Roche, Pfizer, ARIAD, AstraZeneca, Daiivhi Sankyo, Hanmi, Clovis (RF); Saad Khan: Ariad, Genentech, EMG Sevono (C/A); Genzyme (H); Merck, Novartis, Agilent, Threshold, Bayer (RF); Philip J. Stephens: Foundation Medicine (E, OI); Rachel L. Erlich: Foundation Medicine Inc. (E, OI); Vincent A. Miller: Foundation Medicine Inc. (E, OI); Jeffrey S. Ross: Foundation Medicine Inc. (E, RF, OI); Siraj M. Ali: Foundation Medicine Inc. (E, OI, IP). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Supplementary Information

References

- 1. Vergamini LB, Frazier AL, Abrantes FL et al. Increase in the incidence of differentiated thyroid carcinoma in children, adolescents, and young adults: A population‐based study. J Pediatr 2014;164:1481–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cordioli MI, Moraes L, Cury AN et al. Are we really at the dawn of understanding sporadic pediatric thyroid carcinoma? Endocr Relat Cancer 2015;22:R311–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Francis GL, Waguespack SG, Bauer AJ et al. Management guidelines for children with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2015;25:716–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hogan AR, Zhuge Y, Perez EA et al. Pediatric thyroid carcinoma: Incidence and outcomes in 1753 patients. J Surg Res 2009;156:167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Keegan TH, Ries LA, Barr RD et al. Comparison of cancer survival trends in the United States of adolescents and young adults with those in children and older adults. Cancer 2016;122:1009–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown AP, Chen J, Hitchcock YJ et al. The risk of second primary malignancies up to three decades after the treatment of differentiated thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:504–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rubino C, de Vathaire F, Dottorini ME et al. Second primary malignancies in thyroid cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2003;89:1638–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2016;26:1–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wells SA, Robinson BG, Gagel RF et al. Vandetanib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic medullary thyroid cancer: A randomized, double‐blind phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:134–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brose MS, Cabanillas ME, Cohen EE et al. Vemurafenib in patients with BRAF(V600E)‐positive metastatic or unresectable papillary thyroid cancer refractory to radioactive iodine: A non‐randomised, multicentre, open‐label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1272–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shaw AT, Kim D‐W, Nakagawa K et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK‐positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2385–2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pérot G, Soubeyran I, Ribeiro A et al. Identification of a recurrent STRN/ALK fusion in thyroid carcinomas. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e87170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Drilon A, Wang L, Hasanovic A et al. Response to cabozantinib in patients with RET fusion‐positive lung adenocarcinomas. Cancer Discov 2013;3:630–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wong V, Pavlick D, Brennan T et al. Evaluation of a congenital infantile fibrosarcoma by comprehensive genomic profiling reveals an LMNA‐NTRK1 gene fusion responsive to crizotinib. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;108:djv307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Doebele RC, Davis LE, Vaishnavi A et al. An oncogenic NTRK fusion in a patient with soft‐tissue sarcoma with response to the tropomyosin‐related kinase inhibitor LOXO‐101. Cancer Discov 2015;5:1049–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sartore‐Bianchi A, Ardini E, Bosotti R et al. Sensitivity to entrectinib associated with a novel LMNA‐NTRK1 gene fusion in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;108:djv306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prasad ML, Vyas M, Horne MJ et al. NTRK fusion oncogenes in pediatric papillary thyroid carcinoma in northeast United States. Cancer 2016;122:1097–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gertz RJ, Nikiforov Y, Rehrauer W et al. Mutation in BRAF and other members of the MAPK pathway in papillary thyroid carcinoma in the pediatric population. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2016;140:134–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stransky N, Cerami E, Schalm S et al. The landscape of kinase fusions in cancer. Nat Commun 2014;5:4846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell 2014;159:676–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Landa I, Ibrahimpasic T, Boucai L et al. Genomic and transcriptomic hallmarks of poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancers. J Clin Invest 2016;126:1052–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heilmann AM, Subbiah V, Wang K et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of clinically advanced medullary thyroid carcinoma. Oncology 2016;90:339–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grubbs EG, Ng PK‐S, Bui J et al. RET fusion as a novel driver of medullary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:788–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kumagai A, Namba H, Saenko VA et al. Low frequency of BRAFT1796A mutations in childhood thyroid carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:4280–4284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Penko K, Livezey J, Fenton C et al. BRAF mutations are uncommon in papillary thyroid cancer of young patients. Thyroid 2005;15:320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rosenbaum E, Hosler G, Zahurak M et al. Mutational activation of BRAF is not a major event in sporadic childhood papillary thyroid carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2005;18:898–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sassolas G, Hafdi‐Nejjari Z, Ferraro A et al. Oncogenic alterations in papillary thyroid cancers of young patients. Thyroid 2012;22:17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ricarte‐Filho JC, Li S, Garcia‐Rendueles MER et al. Identification of kinase fusion oncogenes in post‐Chernobyl radiation‐induced thyroid cancers. J Clin Invest 2013;123:4935–4944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Givens DJ, Buchmann LO, Agarwal AM et al. BRAF V600E does not predict aggressive features of pediatric papillary thyroid carcinoma. Laryngoscope 2014;124:E389–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leeman‐Neill RJ, Kelly LM, Liu P et al. ETV6‐NTRK3 is a common chromosomal rearrangement in radiation‐associated thyroid cancer. Cancer 2014;120:799–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shaw AT, Kim D‐W, Mehra R et al. Ceritinib in ALK‐rearranged non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1189–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mody RJ, Wu Y‐M, Lonigro RJ et al. Integrative clinical sequencing in the management of refractory or relapsed cancer in youth. JAMA 2015;314:913–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Drilon A, Li G, Dogan S et al. What hides behind the MASC: Clinical response and acquired resistance to entrectinib after ETV6‐NTRK3 identification in a mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC). Ann Oncol 2016;27:920–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang K, Russell JS, McDermott JD et al. Profiling of 149 salivary duct carcinomas, carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenomas, and adenocarcinomas, not otherwise specified reveals actionable genomic alterations. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:6061–6068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fusco A, Grieco M, Santoro M et al. A new oncogene in human thyroid papillary carcinomas and their lymph‐nodal metastases. Nature 1987;328:170–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grieco M, Santoro M, Berlingieri MT et al. PTC is a novel rearranged form of the ret proto‐oncogene and is frequently detected in vivo in human thyroid papillary carcinomas. Cell 1990;60:557–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Greco A, Miranda C, Pagliardini S et al. Chromosome 1 rearrangements involving the genes TPR and NTRK1 produce structurally different thyroid‐specific TRK oncogenes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1997;19:112–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kumar‐Sinha C, Kalyana‐Sundaram S, Chinnaiyan AM. Landscape of gene fusions in epithelial cancers: Seq and ye shall find. Genome Med 2015;7:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Duyster J, Bai RY, Morris SW. Translocations involving anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). Oncogene 2001;20:5623–5637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pearson JD, Lee JKH, Bacani JTC et al. NPM‐ALK: The prototypic member of a family of oncogenic fusion tyrosine kinases. J Signal Transduct 2012;2012:123253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Park G, Kim TH, Lee H‐O et al. Standard immunohistochemistry efficiently screens for anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangements in differentiated thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2015;22:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Godbert Y, Henriques de Figueiredo B, Bonichon F et al. Remarkable response to crizotinib in woman with anaplastic lymphoma kinase‐rearranged anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:e84–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cohen PR. Metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma to the nose: Report and review of cutaneous metastases of papillary thyroid cancer. Dermatol Pract Concept 2015;5:7–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Drilon A, Wang L, Arcila ME et al. Broad, hybrid capture‐based next‐generation sequencing identifies actionable genomic alterations in lung adenocarcinomas otherwise negative for such alterations by other genomic testing approaches. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:3631–3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mukhopadhyay S, Pennell NA, Ali SM et al. RET‐rearranged lung adenocarcinomas with lymphangitic spread, psammoma bodies, and clinical responses to cabozantinib. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:1714–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Michels S, Scheel AH, Scheffler M et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of RET rearranged lung cancer in European patients. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:122–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lipson D, Capelletti M, Yelensky R et al. Identification of new ALK and RET gene fusions from colorectal and lung cancer biopsies. Nat Med 2012;18:382–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Takeuchi K, Soda M, Togashi Y et al. RET, ROS1 and ALK fusions in lung cancer. Nat Med 2012;18:378–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kohno T, Ichikawa H, Totoki Y et al. KIF5B‐RET fusions in lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Med 2012;18:375–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hamatani K, Mukai M, Takahashi K et al. Rearranged anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene in adult‐onset papillary thyroid cancer amongst atomic bomb survivors. Thyroid 2012;22:1153–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Demeure MJ, Aziz M, Rosenberg R et al. Whole‐genome sequencing of an aggressive BRAF wild‐type papillary thyroid cancer identified EML4‐ALK translocation as a therapeutic target. World J Surg 2014;38:1296–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kelly LM, Barila G, Liu P et al. Identification of the transforming STRN‐ALK fusion as a potential therapeutic target in the aggressive forms of thyroid cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:4233–4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vaishnavi A, Capelletti M, Le AT et al. Oncogenic and drug‐sensitive NTRK1 rearrangements in lung cancer. Nat Med 2013;19:1469–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tatematsu T, Sasaki H, Shimizu S et al. Investigation of neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptor 1 fusions and neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptor family expression in non‐small‐cell lung cancer and sensitivity to AZD7451 in vitro. Mol Clin Oncol 2014;2:725–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Menichincheri M, Ardini E, Magnaghi P et al. Discovery of entrectinib: A new 3‐aminoindazole as a potent anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), c‐ros ONCOGENE 1 KINASE (ROS1), and pan‐tropomyosin receptor kinases (Pan‐TRKs) inhibitor. J Med Chem 2016;59:3392–3408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ritterhouse LL, Wirth LJ, Randolph G et al. ROS1‐rearrangement in thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2016;26:794–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cordioli MICV, Moraes L, Carvalheira G et al. AGK‐BRAF gene fusion is a recurrent event in sporadic pediatric thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Med 2016;5:1535–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stransky N, Cerami E, Schalm S et al. The landscape of kinase fusions in cancer. Nat Commun 2014;5:4846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell 2014;159:676–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Landa I, Ibrahimpasic T, Boucai L et al. Genomic and transcriptomic hallmarks of poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancers. J Clin Invest 2016;126:1052–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Waguespack SG, Rich TA, Perrier ND et al. Management of medullary thyroid carcinoma and MEN2 syndromes in childhood. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011;7:596–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Roman S, Lin R, Sosa JA. Prognosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma: Demographic, clinical, and pathologic predictors of survival in 1252 cases. Cancer 2006;107:2134–2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wells SA, Asa SL, Dralle H et al. Revised American Thyroid Association guidelines for the management of medullary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid 2015;25:567–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Höppner W, Ritter MM. A duplication of 12 bp in the critical cysteine rich domain of the RET proto‐oncogene results in a distinct phenotype of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A. Hum Mol Genet 1997;6:587–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bongarzone I, Vigano E, Alberti L et al. The Glu632‐Leu633 deletion in cysteine rich domain of Ret induces constitutive dimerization and alters the processing of the receptor protein. Oncogene 1999;18:4833–4838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Romei C, Elisei R, Pinchera A et al. Somatic mutations of the ret protooncogene in sporadic medullary thyroid carcinoma are not restricted to exon 16 and are associated with tumor recurrence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996;81:1619–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kurzrock R, Sherman SI, Ball DW et al. Activity of XL184 (cabozantinib), an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2660–2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Coyle D, Friedmacher F, Puri P. The association between Hirschsprung's disease and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2a: A systematic review. Pediatr Surg Int 2014;30:751–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kjaer S, Ibáñez CF. Intrinsic susceptibility to misfolding of a hot‐spot for Hirschsprung disease mutations in the ectodomain of RET. Hum Mol Genet 2003;12:2133–2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hyndman BD, Gujral TS, Krieger JR, Cockburn JG, Mulligan LM. Multiple functional effects of RET kinase domain sequence variants in Hirschsprung disease. Hum Mutat 2013;34:132–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Viola D, Valerio L, Molinaro E et al. Treatment of advanced thyroid cancer with targeted therapies: Ten years of experience. Endocr Relat Cancer 2016;23:R185–R205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.