Abstract

Objective

To map and describe the geographic distribution of pediatric hospice care need versus supply in California over a 4-year time period (2007-2010).

Methods

Multiple databases were used for this descriptive longitudinal study. The sample consisted of 2,036 children and adolescent decedents and 136 pediatric hospice providers. Geo-coded data were used to create the primary variables of interest for this study: need and supply of pediatric hospice care. Geographic information systems were used to create heat maps for analysis.

Results

Almost 90% of the children and adolescents had a potential need for hospice care; whereas more than 10% had a realized need. The highest density of potential need was found in the areas surrounding Los Angeles. The areas surrounding the metropolitan communities of Los Angeles and San Diego had the highest density of realized hospice care need. Sensitivity analysis revealed neighborhood level differences in potential and realized need in the Los Angeles area. Over 30 pediatric hospice providers supplied care to the Los Angeles and San Diego areas.

Conclusion

There were distinctive geographic patterns of potential and realized need with high density of potential and realized need in Los Angeles and high density of realized need in the San Diego area. The supply of pediatric hospice care generally matched the needs of children and adolescents. Future research should continue to explore the needs of children and adolescents at end of life at the neighborhood-level, especially in large metropolitan areas.

Keywords: children, adolescents, hospice care, geographic variation, Medicaid, complex chronic conditions

Introduction

According to the most recent United States annual summary of pediatric vital statistics, just over 42,000 children and adolescents die each year with states such as California leading the nation in the number of pediatric deaths.1,2 Life-limiting conditions such as neuromuscular disorders, cancer, and cardiovascular disease are leading causes of health-related mortality among children and adolescents.3 An important approach to caring for children and adolescents with these life-limiting conditions that ensures their physical and psychosocial comfort is pediatric hospice care. Similar to adult hospice care, pediatric hospice services are organized around a collaborative team method of care that focuses on alleviating pain or other symptoms,4 except that pediatric hospice care is targeted to the needs of infants, children, and adolescents and their families.5,6 Pediatric hospice care is delivered in hospitals, freestanding hospice facilities, nursing homes, or the patient’s home.7 The benefits of hospice care have been documented;8 however, fewer than 10% of children and adolescents utilize this end-of-life service.9

Although families, caregivers, and clinicians play a vital role in ensuring utilization to pediatric hospice care 10, emerging evidence suggests geographic access to hospice services for children and adolescents remains a concern. Our initial study of geographic access to pediatric hospice care in Tennessee found that over a three year time period, children with cancer had a potential need for hospice care that was not consistently met by hospice providers across the state.11 Other work has focused on geographic access to hospice care for adults. Lackan and colleagues12 and Campbell and colleagues13 found that the most rural counties are least likely to have a hospice provider. Similarly, Watanabe-Galloway and colleagues found that elderly colorectal cancer patients in rural areas were less likely to use hospice services than were their peers in metropolitan areas.14 However, a study that examined 2002 to 2005 data from cancer decedents in Alabama and found that almost 70% of counties in Alabama contain at least one hospice provider.15 More recently, researchers used 2000 Medicare data and found that 88% of US adults live in communities within a 30 minutes’ drive from a hospice.16 Thus, evidence suggests that the supply of hospice providers may be changing to meet the needs of patients with life-limiting conditions, but it is unclear whether children and adolescents at end of life are impacted by these changes in geographic access to pediatric hospice care.

Understanding geographic access to pediatric hospice care is important because families increasingly desire to bring their children home to die at end of life.17,18 Families have a need for assessible pediatric hospice care in their communities. Geographic factors such as service area, travel distance, and travel time have been shown to influence hospice use. Children and adolescents who reside too far from a pediatric hospice provider or outside the general hospice service area cannot use that hospice's care.19-21 Lengthy travel times due to traffic congestion may also contribute to hospice use, especially in urban areas such as Los Angeles with its notorious traffic jams.21 Knowing more about geographic need and supply of hospice care for children and adolescents may provide important administrative and policy insights for expanding utilization and improving the delivery of hospice care for children. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to map and describe the geographic distribution of pediatric hospice care need versus supply in California over a 4-year time period (2007-2010).

Methods

Data Sources and Sample

Multiple databases were used for this descriptive longitudinal study. The first data source was the 2007 to 2010 California Medicaid claims files (Medicaid Analytic Extract [MAX]). The MAX Person Summary files provided demographic, health status information, and health care services information. The MAX Other Services files provided International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-9) diagnosis codes and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for hospice care services. Medicaid data was used because children with a life-limiting health condition are commonly Medicaid beneficiaries.22 California was chosen because it had the largest population of children enrolled in Medicaid and provided a relatively large sample size.23 The years 2007 to 2010 were chosen because these were the only years that social security date of death was included in the Medicaid data files.

From this pooled, cross-sectional data, a sample of California children and adolescents who died with a life-limiting, complex chronic condition was drawn.24 To be eligible for this study, children and adolescent were less than 21 years of age. Inclusion criteria included children and adolescents who died between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2010 and who were enrolled in the California Medicaid program for any part of their last calendar year of life. Children and adolescents who participated in Medicaid-managed care plans, had missing entries, or were non-California residents were excluded. The final sample was 2,036 children and adolescents decedents, after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The second data source was the 2007 to 2010 California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development State Utilization Data File of Home Health Agency and Hospice Facilities. These data provided administrative and location information on hospices, including latitude and longitude of their primary office.

Hospices that provided care to any child or adolescent with an office address in California were included in the analysis. Hospices that ceased business operation, were home health only agencies, or had missing location data were excluded from the analysis. The final sample of pediatric hospices was 136 pediatric hospice providers. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Measures

We used geocoded data to create the primary variables of interest for this study: need and supply of pediatric hospice care.25 Two separate variables of need for pediatric hospice care were created. Children and adolescents decedents with a life-limiting condition, who did not utilize hospice care were defined as have a potential need for pediatric hospice care. We operationalized potential need as the residence of children and adolescents based on the centroid of the family’s residential zip code. Realized need was defined as dying with a life-limiting condition and utilizing pediatric hospice care. It was also measured as a geographic coordinate based on the centroid of the family’s zip code of residence among children and adolescents who utilized hospice care. Supply of pediatric hospice care was defined as any hospice provider that cared for a child or adolescent during the study timeframe. We operationalized it as the latitude and longitudinal coordinates of a hospice provider that provided any pediatric care services.

Demographic characteristics of the children and adolescents were used to describe the sample. Age was categorized as less than 1 year, 1 to 5 years, 6 to 14 years, or 15 to 20 years and gender was whether the child or adolescent was male or female. Race was Caucasian or non-Caucasian, while ethnicity was Hispanic or not. Individual measures were created for the diagnoses of neurological conditions, cardiovascular conditions, cancer, and congenital anomalies.

Characteristics of pediatric hospice providers were also included. Organizational size was categorized based on average daily census as small (<25 patients/day), medium (26-100 patients/day) or large (101+ patients/day). For-profit or nonprofit/government was the measure of ownership. Affiliation was freestanding or non-freestanding hospice and accreditation was whether the hospice was accredited. Whether or not the hospice had a dedicated pediatric programs was a measure of a pediatric program.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for children and adolescents and hospice providers in the study using Stata 11.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Using geographic information systems, we created heat maps of the geographic distribution of pediatric hospice need and supply. To create maps, ArcGIS Online (ESRI Inc., Redlands, CA) was used. We used a base map of California from the ARCGIS Online system and added our geo-coded data from the children and adolescents and pediatric hospice providers to create a spatial database.26, 27

Because we were interested in assessing hospice need density around a point source (i.e., pediatric hospice provider), we use a focused method of spatial analysis.26, 28 Spatial density analysis involves the detection of clusters in spatial data.29 For this study, we used heat map analysis to visualize the density of hospice need around hospice supply.20 Maps were created using the point density option in ArcGIS Online. Interpretation of the heat map is based on the color of the clusters on the map. Shades of blue represent low density, red is medium density, and yellow is high density. Separate heat maps were created showing the spatial relationships between need (i.e., potential, realized) and supply of pediatric hospice services. Points on the map were used to illustrate the location of hospices that provided any pediatric care. The geo-coded points of pediatric hospice providers were added to the heat maps to identify areas where the need for hospice care matched or did not match the supply of pediatric hospice services. As reference points on the maps the major metropolitan cities of Sacramento, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Fresno, and San Diego were included.

Results

Description of Sample

Table 1 summarizes the children and adolescents decedents from 2007 to 2010. Almost 90% of the children and adolescents in the sample (89.39%) had a potential need for hospice care; whereas 10.6% had a realized need. Among the children and adolescents who used hospice care, their average length of stay in hospice was 26 days, with a range from 1 to 332 days (data not shown). In our study, children and adolescents were most commonly between the ages of 1 and 5 years (32.2%) and male (52.8%). Less than a quarter of the sample was Caucasian (17.2%) and more than a third was Hispanic (36.8%). The frequency of diagnoses were 53.1% for neurological conditions, 40.3% for cardiac conditions, 28.9% for cancer, and 18.4% for congenital anomalies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Children and Adolescent in the Sample, 2007-2010 (N=2,036)

| Characteristics | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Hospice Need | |

| Realized Need | 10.61% |

| Potential Need | 89.39% |

| Age | |

| <1 year | 10.17% |

| 1-5 years | 32.22% |

| 6-14 years | 28.88% |

| 15-20 years | 28.73% |

| Gender | |

| Male | 52.80% |

| Female | 47.20% |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 17.24% |

| Non-Caucasian | 82.76% |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 36.84% |

| Diagnoses | |

| Neurological Conditions | 53.14% |

| Cardiac Conditions | 40.28% |

| Cancer | 28.88% |

| Congenital Abnormalities | 18.37% |

Note: SD = standard deviation

The characteristics of California pediatric hospice providers from 2007 to 2010 are presented in Table 2. Among the pediatric hospices, a majority (61.0%) were medium size providers. Most providers were non-profit/government ownership (64.7%) and freestanding (58.8%). Almost 40% of pediatric hospices (39.7%) were accredited; while only 21.3% of pediatric providers had a dedicated pediatric program. During the study timeframe, California pediatric hospices provided care to 583 children and adolescents (data not shown).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Pediatric Hospice Providers, 2007-2010, (N=136)

| Characteristics | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Organizational Size | |

| Small | 11.76% |

| Medium | 61.03% |

| Large | 27.21% |

| Ownership | |

| For-Profit | 35.29% |

| Non-Profit/Government | 64.71% |

| Affiliation | |

| Freestanding | 58.82% |

| Non-Freestanding | 41.18% |

| Accreditation | |

| Accredited | 39.71% |

| Non-Accredited | 60.29% |

| Pediatric Program | |

| Yes | 21.32% |

| No | 78.68% |

Spatial Analysis

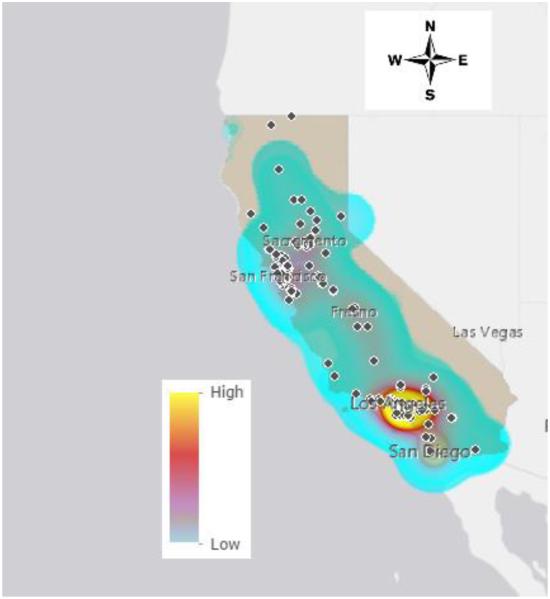

Figure 1 maps the potential need and supply of pediatric hospice care. The potential need for pediatric hospice care was present throughout most of California. There were areas in northern and eastern California were there were no children, who had a potential need for pediatric hospice care. The highest density of potential need was found in the areas surrounding Los Angeles. There was a significant concentration of children and adolescents in Los Angeles who did not utilize pediatric hospice care and yet died with a life-limiting condition. In this high density area, thirty-six hospices supplied pediatric care during the study timeframe. There were no other locations within California with a significant density of potential need for pediatric hospice care.

Figure 1.

Pediatric Hospice Potential Need and Supply in California, 2007-2010

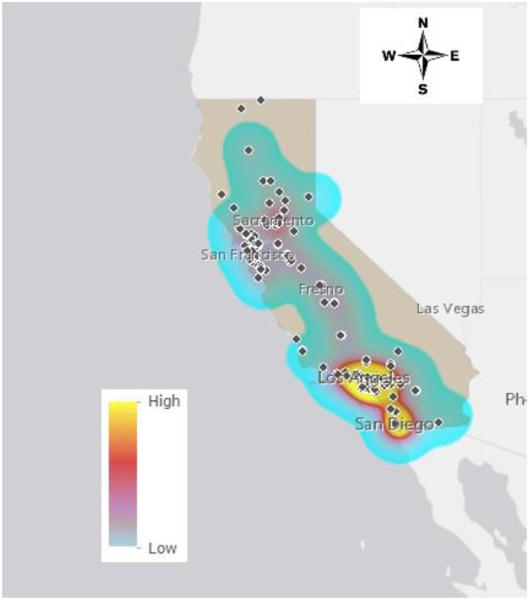

The realized need and supply of pediatric hospice care are illustrated in Figure 2. The realized need for hospice care also varied across California. Generally, children and adolescents had a realized need for pediatric hospice throughout the state. Exceptions were found in northern and eastern California where there was no identified pediatric hospice utilization. The areas surrounding the metropolitan communities of Los Angeles and San Diego had the highest density of realized hospice care need among children and adolescents. In these high density areas, the supply of pediatric hospice providers was thirty-six pediatric providers in the Los Angeles area, and three providers in the San Diego area. There were no other significant clusters of realized need in the state.

Figure 2.

Pediatric Hospice Realized Need and Supply in California, 2007-2010

Discussion

Our study mapped and described the need versus supply of pediatric hospice care over a 4-year period of time in California. We sought to identify the geographic patterns of pediatric hospice care need and supply among children and adolescents at end of life. We used measures of need for pediatric hospice care based on utilization of hospice care, along with a measure of supply of pediatric hospice care based a hospice providing any care to children and adolescents. The study identified critical areas where there were differences in potential and realized need, and yet, these areas often had a supply of pediatric hospice providers.

Our findings demonstrated that there was a consistent potential and realized need for hospice care among children and adolescents that was geographically dispersed across the state of California. This finding is consistent with prior work exploring need for hospice care in Tennessee11 and Alabama.15 Although there were a few areas in the northern and eastern portions of the state where there was no need, we found that the need for hospice care for children and adolescents was geographically distributed across the state.

Interestingly, the study identified that the Los Angeles community had high density of potential need, along with realized need. In other words, children and adolescents who used and did not use hospice care were clustered in and around Los Angeles. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to explore the phenomenon at the neighborhood-level and found there were differences in need among neighborhoods.30 There were clusters of potential need within the inner city of Los Angles, while realized need tended to be present in areas outside the inner city. The Los Angeles is such a large metropolitan area that the needs of children and adolescents in each neighborhood may be sufficiently unique. Clearly, additional research is warranted that explores the geography of need with a different geographic unit of analysis such as the neighborhood.31 This neighborhood research might also include community characteristics to gain a deeper understanding of the potential need for pediatric hospice care.

We also observed a high density of realized need in the San Diego community and a low potential need. A possible explanation of this finding might be the nature of the supply of pediatric hospice providers in the San Diego community during the study time frame. Between 2007 to 2011, the largest provider of pediatric hospice services in California was located in San Diego. The San Diego Hospice was one of the leading hospice providers for children and adolescents in the United States for more than 30 years, and cared for 75 to 100 children and adolescents annually in the San Diego community. This pediatric provider supplied hospice care to a significant number of children and adolescents in the community, which may have reduced the potential need (low clustering), while meeting the realized needs (high clustering). Although our data did not allow us to examine patient outcomes for children and adolescents at end of life, future research might examine geographic variation in end-of-life patient outcomes. In addition, the San Diego Hospice filed for bankruptcy and closed operations in 2013, which was after our study.32 In future studies, it would be interesting to explore the geographic patterns of need versus supply of pediatric hospice care in the aftermath of the closure.

Our study revealed that no areas lacked a supply of pediatric hospice providers to meet needs of children and adolescents at end of life. This finding was consistent with the work of Thompson et al.,33 who reported that there was significant growth in the hospice industry during this timeframe. In addition, Carlson et al. found that 88% of the United States population resided in a community within 30 minutes of a hospice,16 while Jenkins et al. reported similar results in Alabama.15 Among the pediatric hospice providers in our study, we also noted that almost 30% of the pediatric hospice providers did not have a special pediatric program and a majority were medium size. This finding suggests that even though a group of providers may not have dedicated pediatric resources, they were still able to supply the needs of children and adolescents.

Although this was one of the few studies examining the geography of pediatric hospice care, there are a number of limitations. First, this study was conducted with California Medicaid claims data, which limits its generalizability. However, California, has the largest population of pediatric Medicaid residents and is a leader in pediatric hospice care by implementing new and emerging pediatric end-of-life care services.10 As such, exploring geographic variation in California may provide important insight into pediatric end-of-life use and non-use for other states and the nation. Second, the data set included the last calendar year of life for the children and adolescents, and it did not include a comprehensive claims history. Finally, our analysis was descriptive and no causal relations can be drawn from the findings.

In summary, the goal of our study was to improve the understanding of need versus supply of pediatric hospice care at end of life. We found that the need for hospice care was geographically dispersed in the state of California. In addition, there were distinctive patterns of potential and realized need with high density of potential and realized need in Los Angeles and high density of realized need in the San Diego area. We also found that supply of pediatric hospice care generally matched the needs of children and adolescents. Future research should continue to explore the end-of-life care needs of children and adolescents at the neighborhood-level to determine what community, family, and child/adolescent factors might influence potential need. Our study reinforces the necessity of considering geography when targeting care for this underserved population at end of life.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This publication was made possible by Grant Number K01NR014490 from the National Institute of Nursing Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflict of Interest:

The authors declares no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Osterman MJ, Kochanek KD, MacDorman MF, et al. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2012-2013. Pediatr. 2015;135:1115–25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Bastian BA. Deaths: Final data 2013. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2016;64:1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Hospice & Palliative Care Organization 2015 NHPCO facts and figures: Pediatric palliative care and hospice in America. http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/quality/Pediatric_Facts-Figures.pdf Accessed July 29, 2016.

- 4.National Hospice & Palliative Care Organization 2012 NHPCO facts and figures: Hospice care in America. http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2012_Facts_Figures.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2016.

- 5.American Academy of Pediatrics Policy statement on Pediatric Palliative Care and Hospice Care Commitments, Guidelines, and Recommendations. Pediatr. 2013;132(5):966–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2731. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dingfield L, Bender L, Harris P, et al. Comparison of pediatric and adult hospice patients using electronic medical record data from nine hospices in the United States, 2008-2012. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(2):120–6. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindley LC, Mark BA, Lee S-Y. Providing hospice care to children and young adults: A descriptive study of end-of-life organizations. J Hospic Palliativ Nurs. 2009;11(6):315–23. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0b013e3181bcfd62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickens DS. Comparing pediatric deaths with and without hospice support. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54(5):746–50. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindley LC, Lyon ME. A profile of children with complex chronic conditions at end of life among Medicaid-beneficiaries: Implications for healthcare reform. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(11):1388–93. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dabbs D, Butterworth L, Hall E. Tender mercies: increasing access to hospice services for children with life-threatening conditions. Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2007;32(5):311–9. doi: 10.1097/01.NMC.0000288003.10500.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindley LC, Edwards SL. Geographic access to hospice care for children with cancer in Tennessee, 2009 to 2011. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;32:849–54. doi: 10.1177/1049909114543641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lackan NA, Ostir GV, Freeman JL, Mahnken JD, Goodwin JS. Decreasing variation in the use of hospice among older adults with breast, colorectal, lung and prostate cancer. Medical Care. 2004;42(2):116–22. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000108765.86294.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell CL, Merwin E, Yan G. Factors that influence the presence of a hospice in a rural community. J Nurs Scholar. 2009;41(4):420–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe-Galloway S, Wanqing Z, Watkins K, et al. Quality of end-of-life care among rural Medicare beneficiaries with colorectal cancer. J Rural Health. 2014;30:397–405. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins T, Chapman K, Harshbarger D, Townsend JS. Hospice use among cancer decedents in Alabama, 2002-2005. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(4):1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson M, Bradley E, Du Q, Morrison RS. Geographic access to hospice in the United States. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(11):1331–8. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feudtner C, Silveira M, Christakis D. Where do children with complex chronic conditions die? Patterns in Washington state, 1980-1998. Pediatr. 2002;109(4):656–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feudtner C, Feinstein J, Satchell M, Zhao H, Kang T. Shifting place of death among children with complex chronic conditions in the united states, 1989-2003. JAMA. 2007;297(24):2725–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.24.2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casey M, Moscovice I, Virnig B, Durham S. Providing hospice care in rural areas: Challenges and strategies. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2005;22(5):363–8. doi: 10.1177/104990910502200509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heckman T, Somlai A, Peters J, Walker J, Otto L, Galdabini C, Kelly J. Barriers to care among persons living with HIV/AIDS in urban and rural areas. AIDS Care. 1998;10(3):365–75. doi: 10.1080/713612410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waldrop D, Kirkendall A. Rural-urban difference in end-of-life care: Implications for practice. Soc Work Health Care. 2010;49:263–89. doi: 10.1080/00981380903364742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gold JM, Hall M, Shah SS, Thomson J, Subramony A, Mahant S, Mittal V, Wilson KM, Morse R, Mussman GM, Hametz P, Montalbano A, Parikh K, Ishman S, O'Neill M, Berry JG. Long length of hospital stay in children with medical complexity. J Hosp Med. 2016 doi: 10.1002/jhm.2633. epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaiser Family Foundation Distribution of Medicaid Enrollees by Enrollment Group, FY2009. 2010 Available at: http://www.statehealthfacts.org/comparemaptable.jsp?ind=200&cat=4. Accessed 8 August 2012.

- 24.Feudtner C, Hays R, Haynes G, Geyer J, Neff J, Koepsell T. Deaths attributed to pediatric complex chronic conditions: National trends and implications for supportive care services. Pediatr. 2001;107(6):e99–e103. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feldstein PJ. Health Care Economics. Thomson Delmar Learning; Clifton, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cromley EK, McLafferty SL. GIS and Public Health. The Guilford Press; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gomez B, Jones JP. Research Methods in Geography. Wiley-Blackwell; Malden, MA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fotheringham AS, Rogerson PA. The Sage Handbook of Spatial Analysis. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin G, Ming Q. Smart use of State Public Health Data for Health Disparity Assessment. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris R, Sleight P, Webber R. Geodemographics, GIS and Neighborhood Targeting. John Wiley & Sons; West Sussex, England: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearce J, Witten K, Bartie K. Neighborhoods and health: a GIS approach to measuring community resource accessibility. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:389–95. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.043281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faryon J. Medicare audit forces San Diego Hospice to close. KPBS Public Broadcasting. 2013 http://www.kpbs.org/news/2013/feb/13/meidcare-audit-forces-sd-hospice-close/. Accessed 21 July 2016.

- 33.Thompson JW, Carlson MD, Bradley EH. US hospice industry experienced considerable turbulence from changes in ownership, growth, and shift to for-profit status. Health Aff. 2012;31(6):1286–93. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]