Abstract

Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV (PrEP) is recommended for people who inject drugs (PWID). Despite their central role in disease prevention, willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID among primary care physicians (PCPs) is largely understudied. We conducted an online survey (April – May 2015) of members of a society for academic general internists regarding PrEP. Among 250 respondents, 74% (n=185) of PCPs reported high willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID. PCPs were more likely to report high willingness to prescribe PrEP to all other HIV risk groups (p’s<0.03 for all pair comparisons). Compared with PCPs delivering care to more HIV-infected clinic patients, PCPs delivering care to fewer HIV-infected patients were more likely to report low willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID (Odds Ratio [95% CI]= 6.38 [1.48–27.47]). PCP and practice characteristics were not otherwise associated with low willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID. Interventions to improve PCPs’ willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID are needed.

Keywords: HIV prevention, pre-exposure prophylaxis, attitude of health personnel, substance abuse

INTRODUCTION

Globally, approximately 15.9 million people inject drugs, 3.0 million of whom are HIV-infected(1). Notably, injection drug use accounts for 10% of new HIV infections globally(2) and 8% in the United States(3). Evidence-based HIV prevention strategies for people who inject drugs (PWID) include syringe exchange programs; addiction treatment with opioid agonist therapy; HIV testing; antiretroviral treatment of individuals with HIV infection (i.e., “treatment as prevention”); and partner services(4–7). Most recently, pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV (PrEP), the once daily oral use of the antiretroviral medications emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (coformulated as Truvada®), has been found to be efficacious in reducing HIV acquisition among PWID(8). Specifically, the Bangkok Tenofovir study demonstrated that among PWID in the past year (n=2413), daily use of PrEP was associated with a 49% relative risk reduction in HIV incidence, which may be as high as 84% depending on adherence(9, 10). Approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2012, PrEP is now recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for use by PWID as part of an HIV prevention package(11). Specifically, CDC guidelines indicate that PrEP is indicated for any person who has injected non-prescribed drugs in the past 6 months and who reports 1) any sharing of injection or drug equipment in the past 6 months; 2) engagement in medication-assisted therapy for opioid addiction (e.g. methadone, buprenorphine); or 3) risk of sexual acquisition(11). Given the recent outbreak of HIV among PWID in rural Indiana(12) as well as CDC estimates that 115,000 (95% CI 45,000–185,000) PWID across the United States may benefit from PrEP(13), there is urgent need to promote the prescription of PrEP to PWID.

To inform effective strategies for optimizing prescribing of PrEP for PWID, a comprehensive understanding of the perspectives of stakeholders involved in PrEP implementation, including PWID and their health care providers, is important(14). Prior studies conducted among PWID indicate that 35–47% would be willing to take PrEP(15, 16), yet there are limited studies examining provider perspectives regarding willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID and, to date, these have focused on individuals who primarily provide HIV treatment(17–19). Understanding the perspectives of primary care physicians (PCPs), however, is highly relevant as they are ideally suited to deliver PrEP given: 1) the large number of primary care providers in practice(20); 2) their central role in disease prevention; 3) their access to populations of potentially PrEP-eligible patients, including PWID(21); and 4) their ability to expand the workforce of PrEP prescribers to increase access to PrEP(22).

Thus, among a purposeful sample of PCPs practicing in the United States, we evaluated provider willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID compared to other HIV risk groups and to examine provider and practice characteristics associated with low vs. high willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID. These data are important for informing future interventions to improve implementation of PrEP to PWID through primary care.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

From April through May, 2015, we conducted a survey of academic general internists(23). A convenience sample of practicing physicians who were members of the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM), a national medical society of approximately 3,093 physicians based at academic institutions across the United States, were invited to participate. Participants were recruited with informational materials disseminated during a national annual meeting; by emails sent through the online community forum for SGIM members, including an initial invitation and five weekly reminders; and by direct e-mailings. The survey was conducted over a six-week period using Qualtrics® software, a secure web-based survey platform. Individuals were considered eligible to participate if they 1) were SGIM members and 2) provided direct or indirect (i.e. through supervision of trainees) clinical care in an outpatient setting. Participants who completed the survey were offered entry into a raffle to win one of two iPads and given the option to provide contact information. Contact information was kept separate from the de-identified survey responses. The study was reviewed and considered exempt by both Yale University and Albert Einstein College of Medicine’s Humans Investigation Committees.

For this analysis, we included surveys from participants who were 1) SGIM members and 2) provided direct or indirect clinical care. We excluded those surveys from participants where 1) there was missing data on our outcome of interest; and/or 2) duplicate surveys (retaining the more complete record; see below section on Data Quality).

Survey Development and Domains

Initially informed by a prior provider survey(24) and literature review, our 57-item PCP PrEP Survey was developed and refined in an iterative fashion based on piloting and feedback from physicians and researchers with expertise in HIV prevention and treatment as well as community members delivering HIV-related services. The final measures, which were administered as part of a larger survey, included items focused on: 1) PCP sociodemographic, clinical, and practice characteristics; and 2) comfort and willingness to prescribe PrEP to different HIV risk groups (Text Box).

Survey Measures

Outcome of Interest

Willingness to prescribe PrEP to potentially eligible patients was measured through 8 brief patient scenarios (Text Box). These scenarios were developed to be consistent with CDC guidance regarding patients considered to be high risk for HIV and thus eligible for PrEP(11). Participants were asked: “For each of the following risk behavior categories, how willing are you to prescribe PrEP to an eligible individual, assuming a recent negative HIV test and equal access to medication?” Our outcome of interest, willingness to prescribe to PWID who shares injection equipment (referred to as “PWID”), was determined based on participants’ responses to how willing they were to prescribe PrEP to “a person who has injected drugs in the past 6 months and shared injection equipment.” Responses were measured on a 4-point Likert scale (1=not at all; 4=extremely). Responses were analyzed as a continuous variable and, to promote ease of interpretation and because they were negatively skewed, were then dichotomized as low (1 or 2) vs. high (3 or 4) willingness to prescribe. Other risk behavior categories included men and women in an HIV serodiscordant relationship; heterosexual relationship with partners at HIV risk; men who have sex with men. In addition, we also assessed willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID recently engaged in methadone treatment.

Independent Variables

We measured PCP characteristics, including age; race/ethnicity; gender; sexual orientation; current medical role; years in practice; and percent of time allocated to different professional activities. Measured clinical and practice characteristics included practice location based on region of the country and urbanicity (i.e. urban, suburban or rural practice setting) as well as type of clinical setting (i.e. clinic at an academic medical center; clinic at public hospital; community health center; clinic at VA hospital; or other). Lastly, we asked about number of HIV-infected patients in the provider’s patient panel. Response options (i.e. 0, 1–10, 11–20, 21–50, 51–100, 101–200, and >200) were dichotomized into ≤20 vs. >20 based on thresholds required for demonstrating clinical expertise in HIV care(25). In sensitivity analyses, we also dichotomized this variable as 0 vs. >0 and ≤10 vs. >10.

Data Quality

To minimize inclusion of duplicate survey responses, we reviewed responses patterns for records generated from the same Internet Protocol (IP) address. Surveys that were associated with the same IP address and had at least 80% duplication of responses were considered to be redundant. We also evaluated the survey completion duration (time of last response minus survey initiation) to ensure a reasonable amount of time was used to complete the survey.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the analytic sample. We then evaluated physician willingness to prescribe PrEP across risk groups using Multiple Analysis of Variance (MANOVA), with post-hoc pair comparisons. In addition, low vs. high willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID vs. other risk groups were evaluated using Generalized Estimating Equations with follow-up pair comparisons. Next, to compare PCP and practice characteristics associated with low vs. high willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID, we used chi-square tests and t-tests. We considered p<0.05 to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS/PASW 21.0 software (IBM Corporation, Somers, NY).

RESULTS

Provider and Practice Characteristics

Among the 363 providers who initiated the survey, we excluded those who were not SGIM members (n=64), did not provide clinical care (n=12), or had a duplicate survey (n=3); reflecting an estimated response rate of 9% among potential participants (Figure 1). For this analysis, we additionally excluded surveys missing responses to the outcome of interest (n=34). Median duration for completing the survey was 7 minutes (IQR 5–10). Among the 250 providers, the mean age was 41 years and the majority were white (72%), non-Hispanic (92%), women (62%) and heterosexual (92%) (Table 1). Most were attending physicians (79%), where half of participants had been in practice for less than 10 years and the greatest percent of their time allocated to direct patient care.

Figure 1.

Analytic Sample

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics, Overall and By Willingness to Prescribe PrEP to People who Inject Drugs

| Characteristics | Overall (n=250) | Low Willingness to Prescribe PrEP to People Who Inject Drugs (n=65) | High Willingness to Prescribe PrEP to People who inject drugs (n=185) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 41.0 (9.6) | 40.9 (8.7) | 41.1 (9.9) | 0.89 |

|

| ||||

| Race, n (%) | 0.28 | |||

| White | 172 (72%) | 39 (63%) | 133 (76%) | |

| Black | 13 (6%) | 5 (8%) | 8 (5%) | |

| Asian/Asian American | 43 (18%) | 15 (24%) | 28 (16%) | |

| Other | 10 (4%) | 3 (5%) | 7 (4%) | |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity, % Hispanic | 18 (8%) | 5 (8%) | 13 (7%) | 0.88 |

|

| ||||

| Gender, n (%) | 0.31 | |||

| Female | 155 (62%) | 38 (58%) | 117 (64%) | |

|

| ||||

| Sexual Orientation, n (%) | 0.45 | |||

| Heterosexual | 227 (92%) | 61 (94%) | 166 (91%) | |

| Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual/ | 20 (8%) | 4 (6%) | 16 (9%) | |

| Other | ||||

|

| ||||

| Role, n (%) | 0.50 | |||

| Attending Physician | 195 (79%) | 53 (82%) | 142 (78%) | |

| Fellow/resident | 53 (21%) | 12 (18%) | 41 (22%) | |

|

| ||||

| Years in Practice, n (%)* | 0.60 | |||

| <10 | 94 (50%) | 27 (53%) | 67 (48%) | |

| >10–15 | 37 (20%) | 11 (22%) | 26 (19%) | |

| >15 | 59 (31%) | 13 (25%) | 46 (33%) | |

|

| ||||

| Percent of time allocation, Mean (SD) | 0.24 | |||

| Direct patient care | 42.3 (29.4) | 35.6 (26.9) | 44.7 (30.0) | |

| Research | 21.1 (29.2) | 23.0 (29.3) | 20.4 (29.3) | |

| Medical education | 21.5 (20.3) | 23.0 (21.9) | 21.0 (19.7) | |

| Administration | 13.4 (17.8) | 16.1 (19.4) | 12.4 (17.2) | |

| Other | 1.7 (8.1) | 2.4 (12.2) | 1.5 (6.1) | |

Note: Based on 190 responses as responses were otherwise missing.

Nearly half of providers practiced in the northeast (49%). Most providers were based in urban (85%) clinics at an academic medical center (68%) and provided care for 20 or fewer HIV-infected patients (86%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Practice Characteristics, Overall and by Willingness to Prescribe to People who Inject Drugs

| Characteristics | Overall | Low Willingness to Prescribe PrEP to People who Inject Drugs | High Willingness to Prescribe PrEP to People who Inject Drugs | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Region of Country, n (%) | 0.69 | |||

| West | 42 (17%) | 12 (18%) | 30 (16%) | |

| Midwest | 35 (14%) | 10 (15%) | 25 (14%) | |

| South | 49 (20%) | 15 (23%) | 34 (18%) | |

| Northeast | 123 (49%) | 28 (43%) | 95 (52%) | |

|

| ||||

| Rurality/Urbanicity of practice, n (%) | 0.92 | |||

| Urban | 213 (85%) | 55 (85%) | 158 (85%) | |

| Suburban | 31 (12%) | 8 (12%) | 23 (12%) | |

| Rural | 6 (2%) | 2 (3%) | 4 (2%) | |

|

| ||||

| Type of clinical setting, n (%) | 0.57 | |||

| Clinic at an academic medical center | 171 (68%) | 44 (68%) | 127 (69%) | |

| Clinic at public hospital | 24 (10%) | 8 (12%) | 16 (9%) | |

| Community health center | 22 (9%) | 3 (5%) | 19 (10%) | |

| Clinic at VA hospital | 15 (6%) | 4 (6%) | 11 (6%) | |

| Other | 18 (7%) | 6 (9%) | 12 (6%) | |

|

| ||||

| # of clinic patients with HIV, n (%) | 0.01 | |||

| ≤20 | 216 (86%) | 63 (97%) | 153 (83%) | |

| >20 | 33 (14%) | 2 (3%) | 31 (16%) | |

Willingness to Prescribe PrEP to PWID vs. Other HIV Risk Groups

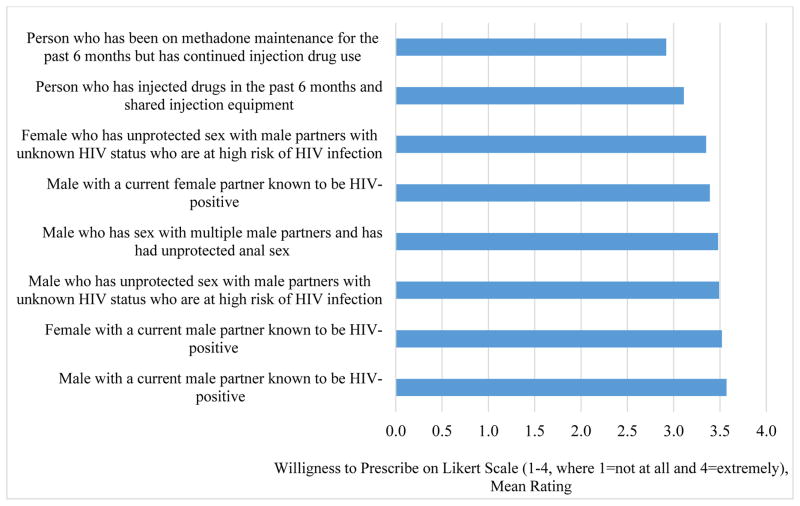

Mean ratings (1–4 scale) of willingness to prescribe PrEP ranged from 2.92 to 3.57 (p<0.001) (Figure 2). Mean ratings were highest for those scenarios describing a male (3.57) or female (3.52) in a HIV serodiscordant relationship with a male partner. Compared to all risk groups, the mean ratings were lowest for the scenario describing PWID (3.11, p’s <0.001 for all pair comparisons). The only exception to these findings was that, compared to willingness to prescribed PrEP to a PWID, the mean rating of willingness to prescribe PrEP to a PWID with recent engagement in methadone treatment was even lower (2.92, p<0.001).

Figure 2.

PCP’s Rating of their Willingness to Prescribe PrEP by HIV Risk Group

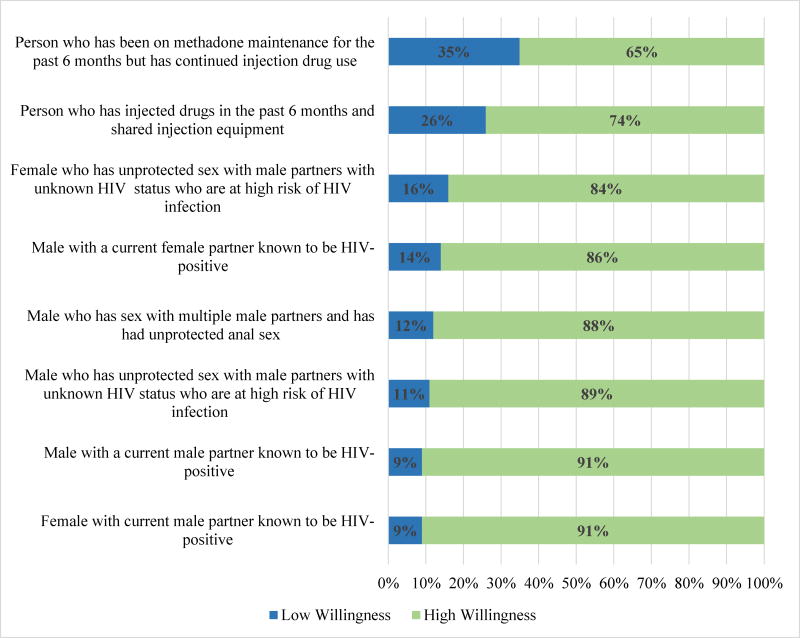

These findings were consistent when we evaluated low vs. high provider willingness to prescribe PrEP across HIV risk groups with GEE, where reported high willingness to prescribe PrEP ranged from 65% to 91% (overall GEE Wald X2 = 86.68, p<0.001) (Figure 3). The proportion of providers reporting high willingness to prescribe PrEP was greatest for those scenarios describing a female or male in a HIV serodiscordant relationship with a male partner (91% for both). In contrast, the proportion of providers reporting high willingness to prescribe PrEP was lowest for the scenario describing PWID (74%). The proportion of providers reporting high willingness to prescribe PrEP to a PWID was significantly lower compared to all other risk groups (p’s <0.03 for all pair comparisons). Again, the only exception to these findings was that, compared to willingness to prescribe PrEP to a PWID, the proportion of providers reporting high willingness to prescribe PrEP to a PWID with recent engagement in methadone treatment was even lower (65%, p=0.02).

Figure 3.

PCP’s Low vs. High Willingness to Prescribe PrEP by HIV Risk Group

Characteristics by Willingness to Prescribe PrEP to PWID

Compared to providers with high willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID, providers with low willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID were similar in terms of almost all provider and practice characteristics (Tables 1 and 2). Only number of HIV-infected patients under the providers’ care was significantly associated with willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID; compared with providers with more than 20 HIV-infected clinic patients (6%, 2/33), providers delivering care to 20 or fewer HIV-infected patients were more likely to report low willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID (29%, 63/219; Odds Ratio [95% CI]= 6.38 [1.48–27.47]). In sensitivity analyses, compared to providers delivering care to zero HIV-infected patients, providers delivering care to at least one were not significantly likely to report low willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID (OR [95% CI]= 1.61 [0.86–3.01]). However, compared to providers delivering care to more than 10 HIV-infected patients, providers delivering care to 10 or fewer HIV-infected patients were more likely to report low willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID (OR [95% CI]= 2.38 [1.05–5.35]).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID relative to other HIV risk groups among a sample of PCPs. First, over a quarter of these PCPs reported low willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID despite CDC clinical guidance which recommends PrEP for PWID at substantial risk for HIV infection. Second, a significantly greater proportion of these PCPs reported a low willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID compared to all other risk groups, including high risk heterosexual men and women and men who have sex with men. Third, among all examined PCP and practice characteristics, only the number of HIV-infected clinic patients for whom the PCP provided care was found to be significantly associated with provider willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID. Lastly, we found that provider willingness to prescribe PrEP to a PWID with recent engagement in methadone treatment was lowest compared to all risk groups.

Our findings drawn from a sample of PCPs compare and contrast with previous findings reported based on surveys focused on HIV providers(17–19). For example, Krakower and colleagues found that among a national sample of Infectious Disease physicians (n=573), only 42% of physicians endorsed beliefs that PrEP should be offered routinely to PWID(17). In their survey of Washington, D.C. and Miami, Florida-based HIV providers (n=142), Castel and colleagues similarly demonstrated that low proportions of providers were likely to prescribe PrEP to PWID, and these proportions were smaller than the proportions likely to prescribe PrEP to men who have sex with men (but similar to the proportions likely to prescribe to individuals with multiple partners)(18). In their survey of American Academy of HIV Medicine Providers (n=363), Adams and Balderson found that 45% of providers were very likely to prescribe PrEP to those who inject drugs(19). This was similar to the proportion of providers reporting that they were very likely to prescribe PrEP to a high-risk heterosexual (47%), but also lower compared to each scenario describing a man who has sex with men at high HIV risk.

Given their potential central role in delivering PrEP to PWID, it is concerning that considerable proportions of HIV specialists and PCPs alike do not appear ready or willing to provide PrEP to PWID, including those engaged in addiction treatment, and that they are less willing to provide PrEP for PWID compared to other HIV risk groups. These findings parallel negative provider attitudes seen with regards to prescribing of antiretroviral therapy to HIV-infected PWID(12, 26–28), attitudes which may contribute to decreased antiretroviral therapy access and worse outcomes among HIV-infected PWID. Reasons for these findings are likely multi-factorial, and may include concerns regarding patient medication adherence and ability to remain engaged in care(10). However, lack of provider comfort in treating addiction-related issues(17); stigma; and structural barriers may also contribute(29). Though the results from prior studies are not directly comparable given differences in measures, populations and timing of surveys, the current findings suggest that some PCPs may be as or more willing to prescribe PrEP to PWID than HIV providers (22 – 45%)(17–19).

Not surprisingly, providers with 20 or fewer HIV-infected patients were more likely to report low willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID. This may reflect a lower comfort level with antiretrovirals and inappropriately heightened concerns regarding adherence by PWID among providers with less experience treating HIV-infected patients compared to providers with greater experience treating HIV-infected individuals(28, 30). We did not find that other factors which may relate to experience treating PWID (e.g. urbanicity of practice) were significantly associated with willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID. This may relate to a lack of power due to our relatively small sample size or lack of true effect in this sample of academically-based PCPs.

This study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional analysis limiting our ability to make casual inferences. Second, results are based on a convenience sample of PCPs drawn from membership of a society for academic PCPs and had a low response rate. As such, these findings may not be generalizable to all academic internists and those based in non-academic settings and are more likely to reflect perspectives of physicians with an interest in HIV prevention and/or treatment. However, our recruitment materials and strategy were specifically designed to appeal to the general audience and our response rate was comparable to other provider surveys(31–33), including those focused on PrEP(19, 34). Third, given that knowledge regarding PrEP is quickly expanding, these findings may not reflect the most recent PCP prescribing trends. However, that less than 80,000 individuals across the United States have initiated PrEP across risk groups demonstrates a continued need to promote PrEP(35). Fourth, our measures rely on self-report, rather than actual prescribing practices, and may be subject to social desirability bias. Fifth, given the relatively low response rate and sample size, we may have been underpowered to detect significant differences in factors associated with willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID.

These limitations notwithstanding, results from this study have important implications for practice and future study. First, future studies should examine whether our findings extend to non-academically based primary care providers to inform expansion of PrEP to PWID. Second, our findings suggest that in-depth exploration regarding the reasons underlying PCPs’ unwillingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID are needed. Such information could directly inform the development and evaluation of future provider-based interventions. Third, comprehensive strategies for reaching PWID to deliver HIV prevention strategies in addiction-focused settings, such as opioid treatment programs or needle-exchange programs, where providers have more experience treating PWID may be needed(36, 37).

In conclusion, in an informative sample of PCPs practicing in academic settings in the United States, we found that over a quarter of individuals reported low willingness to prescribe PrEP to PWID. This was especially true among providers caring for less than 20 HIV-infected patients. PCPs are key stakeholders in the process of PrEP provision and their engagement will be necessary to reach the estimated 115,000 PWID across the United States who may benefit from PrEP. Thus, future efforts to optimize utilization of PrEP among PWID ought to target PCPs to promote HIV disease prevention and include PrEP in prevention education with PWID.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms. Katz for her assistance with programming the survey. A version of this work was presented as a poster presentation at the College on Problems of Drug Dependence Annual Meeting, June 16th, 2016 in Palm Springs, California.

FUNDING

This work was generously supported by Yale Center for Clinical Investigation (UL1 TR000142). EJ Edelman was supported as a Yale Drug Abuse, Addiction and HIV Research Scholars (DAHRS) Program during the writing of this manuscript (K12DA033312-03). BA Moore is supported by R01 DA034678. SK Calabrese is supported by K01-MH103080. O Blackstock is supported by K23MH102129-03.

Text Box. Patient Scenarios: Individuals with high risk for HIV and PrEP Indication.

| Men who have sex with men | Heterosexual Women and Men | People with injection drug use |

|---|---|---|

| A male who has unprotected sex with male partners with unknown HIV status who are at high risk of HIV infection (e.g., partner(s) who has sex with other males or uses injection drugs) | A female with a current male partner known to be HIV-positive | A person who has injected drugs in the past 6 months and shared injection equipment |

| A male with a current male partner known to be HIV-positive | A female who has unprotected sex with male partners with unknown HIV status who are at high risk of HIV infection (e.g., partner(s) who has sex with other males or uses injection drugs) | A person who has been on methadone maintenance for the past 6 months but has continued injection drug use |

| A male who has sex with multiple male partners and has had unprotected anal sex | A male with a current female partner known to be HIV-positive |

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Fiellin has received honoraria from Pinney Associates for serving on an external advisory board monitoring the diversion and abuse of buprenorphine. The authors have no other conflicts of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was reviewed and considered exempt by both Yale University and Albert Einstein College of Medicine’s Humans Investigation Committees.

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

References

- 1.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee SA, et al. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet. 2008;372(9651):1733–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strathdee SA, Stockman JK. Epidemiology of HIV among injecting and non-injecting drug users: current trends and implications for interventions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(2):99–106. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0043-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. 2012 Dec; Report No. [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacArthur GJ, van Velzen E, Palmateer N, Kimber J, Pharris A, Hope V, et al. Interventions to prevent HIV and Hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: a review of reviews to assess evidence of effectiveness. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(1):34–52. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gowing L, Farrell MF, Bornemann R, Sullivan LE, Ali R. Oral substitution treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD004145. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004145.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Des Jarlais DC, Kerr T, Carrieri P, Feelemyer J, Arasteh K. HIV infection among persons who inject drugs: Ending old epidemics and addressing new outbreaks. AIDS. 2016 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO, UNODC, UNAIDS TECHNICAL GUIDE FOR COUNTRIES TO SET TARGETS FOR UNIVERSAL ACCESS TO HIV PREVENTION, TREATMENT AND CARE FOR INJECTING DRUG USERS. 2012 revision.

- 8.Escudero DJ, Lurie MN, Kerr T, Howe CJ, Marshall BD. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for people who inject drugs: a review of current results and an agenda for future research. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:18899. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. The impact of adherence to preexposure prophylaxis on the risk of HIV infection among people who inject drugs. AIDS. 2015;29(7):819–24. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Public Health Service. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States - 2014: A Clinical Practice Guideline. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loughlin A, Metsch L, Gardner L, Anderson-Mahoney P, Barrigan M, Strathdee S. Provider barriers to prescribing HAART to medically-eligible HIV-infected drug users. AIDS Care. 2004;16(4):485–500. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001683411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith DK, Van Handel M, Wolitski RJ, Stryker JE, Hall HI, Prejean J, et al. Vital Signs: Estimated Percentages and Numbers of Adults with Indications for Preexposure Prophylaxis to Prevent HIV Acquisition - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(46):1291–5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6446a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Underhill K, Operario D, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer MR, Mayer KH. Implementation science of pre-exposure prophylaxis: preparing for public use. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(4):210–9. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0062-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stein M, Thurmond P, Bailey G. Willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among opiate users. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1694–700. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0778-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escudero DJ, Kerr T, Wood E, Nguyen P, Lurie MN, Sued O, et al. Acceptability of HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PREP) Among People Who Inject Drugs (PWID) in a Canadian Setting. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(5):752–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0867-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krakower DS, Beekmann SE, Polgreen PM, Mayer KH. Diffusion of Newer HIV Prevention Innovations: Variable Practices of Frontline Infectious Diseases Physicians. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(1):99–105. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castel AD, Feaster DJ, Tang W, Willis S, Jordan H, Villamizar K, et al. Understanding HIV Care Provider Attitudes Regarding Intentions to Prescribe PrEP. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70(5):520–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams LM, Balderson BH. HIV providers’ likelihood to prescribe pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention differs by patient type: a short report. AIDS Care. 2016:1–5. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1153595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Primary Care Physicians by Field [5.14.2016] 2016 Apr; [Available from: http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/primary-care-physicians-by-field/

- 21.Artenie AA, Jutras-Aswad D, Roy E, Zang G, Bamvita JM, Levesque A, et al. Visits to primary care physicians among persons who inject drugs at high risk of hepatitis C virus infection: room for improvement. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22(10):792–9. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krakower D, Ware N, Mitty JA, Maloney K, Mayer KH. HIV providers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis in care settings: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1712–21. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0839-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blackstock OJ, Moore BA, Berkenblit GV, Calabrese SK, Cunningham CO, Fiellin DA, et al. HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Adoption among Primary Care Physicians: Implications for Implementation. under review. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3903-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lum PJ, Little S, Botsko M, Hersh D, Thawley RE, Egan JE, et al. Opioid-prescribing practices and provider confidence recognizing opioid analgesic abuse in HIV primary care settings. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(Suppl 1):S91–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820a9a82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Academy of HIV Medicine. Practicing HIV Specialist (AAHIVS) [cited 2016 9.17.2016]. Available from: http://www.aahivm.org/aahivs.

- 26.Westergaard RP, Ambrose BK, Mehta SH, Kirk GD. Provider and clinic-level correlates of deferring antiretroviral therapy for people who inject drugs: a survey of North American HIV providers. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-15-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bogart LM, Kelly JA, Catz SL, Sosman JM. Impact of medical and nonmedical factors on physician decision making for HIV/AIDS antiretroviral treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;23(5):396–404. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200004150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding L, Landon BE, Wilson IB, Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Cleary PD. Predictors and consequences of negative physician attitudes toward HIV-infected injection drug users. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(6):618–23. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.6.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baral SD, Stromdahl S, Beyrer C. The potential uses of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among people who inject drugs. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(6):563–8. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328358e49e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malta M, Magnanini MM, Strathdee SA, Bastos FI. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected drug users: a meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(4):731–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9489-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.VanGeest JB, Johnson TP, Welch VL. Methodologies for improving response rates in surveys of physicians: a systematic review. Eval Health Prof. 2007;30(4):303–21. doi: 10.1177/0163278707307899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dykema J, Stevenson J, Day B, Sellers SL, Bonham VL. Effects of incentives and prenotification on response rates and costs in a national web survey of physicians. Eval Health Prof. 2011;34(4):434–47. doi: 10.1177/0163278711406113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klabunde CN, Willis GB, McLeod CC, Dillman DA, Johnson TP, Greene SM, et al. Improving the quality of surveys of physicians and medical groups: a research agenda. Eval Health Prof. 2012;35(4):477–506. doi: 10.1177/0163278712458283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krakower DS, Oldenburg CE, Mitty JA, Wilson IB, Kurth AE, Maloney KM, et al. Knowledge, Beliefs and Practices Regarding Antiretroviral Medications for HIV Prevention: Results from a Survey of Healthcare Providers in New England. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mera RMS, Palmer B, Mayer G, Magnuson D, Rawlings K. AIDS. Durban; South Africa: 2016. Truvada (TVD) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization in the United States (2013–2015) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edelman EJ, Dinh AT, Moore BA, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA, Sullivan LE. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Testing Practices Among Buprenorphine-prescribing Physicians. J Addict Med. 2012;6(2):159–65. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31824339fc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Underhill K, Morrow KM, Colleran CM, Holcomb R, Operario D, Calabrese SK, et al. Access to healthcare, HIV/STI testing, and preferred pre-exposure prophylaxis providers among men who have sex with men and men who engage in street-based sex work in the US. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]