Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) commonly require intensive care unit (ICU) support, but risk factors for ICU admission and adverse outcomes remain poorly defined.

OBJECTIVE

We utilized the University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) database to examine risk factors, mortality, length of stay (LOS), and cost associated with ICU admission for AML patients.

DESIGN

The UHC is a hospitalization database that contains demographic, clinical, and cost variables prospectively abstracted by certified coders from discharge summaries and cost charges generated by UHC institutions from 2004–2012. We extracted information from AML patients based on ICD-9 codes. Outcomes were analyzed using univariate and multivariate statistical techniques.

SETTING

229 member hospitals of the UHC, composed of academic centers and their affiliated hospitals from 43 U.S. states.

PARTICIPANTS

We identified 43,249 patients with AML ≥18 years of age with active AML hospitalized for any cause at UHC hospitals during the timeframe. We excluded patients who had previously undergone hematopoietic cell transplantation.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Primary outcomes were ICU admission and inpatient mortality among ICU patients. Secondary outcomes included ICU and total hospitalization LOS and cost.

RESULTS

26.1% of identified AML patients required ICU admission. Independent risk factors for ICU admission included age <80 years (odds ratio [OR] =1.56), hospitalization in the South (OR=1.81), hospitalization at a small/medium hospital (OR=1.25), ≥1 comorbidity (OR=10.64 for 5 comorbidities), sepsis (OR=4.61), fungal infection (OR=1.24) and pneumonia (OR=1.73). In-hospital mortality was higher for patients requiring ICU care (43.1% vs. 9.3%), with independent risk factors for death in those patients including age ≥60 (OR=1.16), non-white ethnicity (OR=1.18), hospitalization on the West Coast (OR=1.19), comorbidity burden (OR 18.76 for 5 comorbidities), sepsis (OR=2.94), fungal infection (OR=1.20), and pneumonia (OR=1.13). Mean hospitalization costs were higher for patients requiring ICU care ($83,354 vs. $41,973) and increased with each comorbidity from $50,543 to $124,820 for those with 0 vs. ≥5 comorbidities.

CONCLUSION

ICU admission is associated with high mortality and cost that increase proportionally with the comorbidity burden in adult AML. Several demographic factors and medical characteristics identify patients at risk for ICU admission and mortality and provide an opportunity for testing primary prevention strategies.

INTRODUCTION

The survival of adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has gradually improved over the last four decades, largely due to improvements in supportive care and hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), with some headway made in therapeutic strategies.1–3 While contributing to improved survival, contemporary high-intensity AML therapies bear the risk of complications that require intensive care unit (ICU)-level care. Despite advances in ICU management strategies for hematologic malignancies,4–6 ICU care remains associated with substantial mortality and long-term sequelae.7–10

Few studies have examined risk factors for ICU admission in AML patients, with limited data pointing to a role of age, comorbidities, infection, and therapeutic regimens.10,11 Conversely, retrospective studies have identified a larger number of possible risk factors for mortality after ICU admission in patients with a wider range of hematologic malignancies including performance status, APACHE score, organ failure, ventilator need, and vasopressors use.4,9,10,12–15 However, most of these studies were small, single-institution investigations, limiting generalizability given variability across ICUs.16 Furthermore, few studies have focused specifically on AML, although some evidence indicates that outcomes in AML are particularly poor.13,14 Finally, while of great interest from a medical and economic perspective, effects of ICU stays on healthcare resource utilization, length of stay (LOS), and costs have not been evaluated.

Understanding relevant risk factors for ICU admission and short-term mortality, the primary goal of this study, is an essential step in identifying patients at high risk for adverse events. This would allow for the development of pre-emptive strategies aimed at optimizing treatment outcomes and reducing the economic impact of AML therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source

The University Health System Consortium (UHC) constitutes a collaboration between academic and affiliated health institutions for the purposes of research and clinical practice analysis.17 Currently, the UHC includes 117 academic centers with 338 affiliated hospitals throughout the U.S., representing 43 states. The consortium established a longitudinal hospitalization database comprising a set of pre-specified clinical variables (not including laboratory, radiologic, or pathologic data, or cause of death) prospectively abstracted by certified coders from discharge summaries, and cost charges generated by consortium institutions. Data collection is closely monitored and strictly quality controlled to ensure data completeness. For this analysis, no direct patient or institutional identifiers were provided to the investigators.

Patient Population

The study population consisted of all adults ≥18 years of age with newly diagnosed or relapsed/refractory AML hospitalized for any cause between 2004 and 2012 at UHC member hospitals. To identify patients of interest, inclusion criteria were developed based on the ninth revision of the International Classification of Diseases-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. All claims had to contain at least one diagnosis for active AML based on ICD-9 criteria (codes 205.00, 205.02, 205.30, 205.32, 206.00, 206.02, 207.00, and 207.02), which included patients admitted for therapy for AML or complications from AML or its treatment. Patients with a concurrent code for myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) were included. Admissions of patients with AML in remission, those who had undergone HCT on the current or prior admission, and patients with other cancers were not included. For patients with more than one admission during the observation period, one random hospitalization was selected for analysis, as was done in prior similar studies using this database.18

Study Outcomes and Independent Variables

Primary outcomes for analysis were ICU admission and inpatient mortality among those requiring ICU care. Secondary outcomes included total hospitalization LOS, ICU LOS, and cost. Independent variables included age, gender, race (white, black, Hispanic, Asian, other/unknown), hospitalization year, geographic location, hospital volume, comorbidities, infections, and procedures. Hospital size was extrapolated from the number of cancer patients admitted per year, with volumes defined as small (<3,000 cancer admission/year), medium (3,000–6,000 cancer admissions/year), and large (>6,000 cancer admissions/year). Comorbidities, infections, and procedures were examined based on 99 available diagnostic codes. Comorbidities included congestive heart failure, other heart diseases, lung disease, liver disease, renal disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. Infections included both type and site of infection encompassing bacterial infections, fungal infections, invasive candida, invasive aspergillosis, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, indwelling catheter infection, and sepsis. Procedures of interest were red blood cell or platelet transfusions and in-hospital chemotherapy. Total costs per admission were provided by the consortium, adjusted for inflation, and converted to 2014 U.S. dollars using the U.S. Department of Labor’s Consumer Price Index Inflation calculator.19

Statistical Methods

For univariate analysis of binary outcomes, risk categories were compared using unadjusted odds ratios (OR). The age variable was split into separate categories increasing by 10, starting at 40. The final cut-point was chosen based on the proportion with ICU admissions by age category. For continuous variables (LOS, cost), linear regression was used to compare differences between categories after natural logarithm transformation of both outcomes. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to evaluate associations of covariates with risk of ICU admission and mortality among patients requiring ICU care. For each model separately, the covariates were first screened by stepwise regression (p=0.05 required for model entry and elimination). The final model included the demographic and clinical variables that were associated with increased risk during the selection process. The standard error (SE) and associated confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using Wald’s method. In addition, to adjust for correlation between observations from the same hospital, robust SEs and CIs were calculated using generalized estimating equation methods. Wald CIs are presented within the text. Statistical analysis was performed using a software program (SAS version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 126,076 hospitalizations were reported for 49,530 patients with AML at 229 hospitals from 2004–2012, with 52.7% of patients admitted more than once. We excluded 6,281 patients with a history of HCT (5,996 allogeneic and 285 autologous), leaving 43,249 for final analysis. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics, major comorbidities, and infections separately for the 11,277 (26.1%) patients who did and the 31,972 (73.9%) patients who did not require ICU admission during the analyzed hospitalization.

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics (n=43,249)

| Patients without ICU Stay |

Patients requiring ICU stay |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| All AML patients | 31,972 (100.0) | 11,277 (100.0) | |

| Age, mean (range) | 59.5 (18–90+) | 59.5 (18–90+) | |

| 18–65 | 18,231 (57.0) | 6,589 (58.4) | |

| 65+ years | 13,741 (43.0) | 4,688 (41.6) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 17,476 (54.7) | 6,463 (57.3) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 23,375 (73.1) | 8,069 (71.6) | |

| Black | 2,998 (9.4) | 1,277 (11.3) | |

| Hispanic | 1,606 (5.0) | 486 (4.3) | |

| Asian | 833 (2.6) | 262 (2.3) | |

| Geographic region | |||

| NorthEast | 9,701 (30.3) | 3,088 (27.4) | |

| Central | 10,013 (31.3) | 3,238 (28.7) | |

| West Coast | 5,597 (17.5) | 1,661 (14.7) | |

| Southern | 6,422 (20.1) | 3,205 (28.4) | |

| Hospital Size | |||

| Small | 5,345 (16.7) | 1,894 (16.8) | |

| Medium | 14,483 (45.3) | 5,514 (48.9) | |

| Large | 12,144 (38.0) | 3,869 (34.3) | |

| Number of comorbidities | |||

| 0 | 8,677 (27.1) | 1,063 (9.4) | |

| 1 | 10,157 (31.8) | 1,993 (17.7) | |

| 2 | 7,712 (24.1) | 2,770 (24.6) | |

| 3 | 3,879 (12.1) | 3,024 (26.8) | |

| 4 | 1,286 (4.0) | 1,778 (15.8) | |

| 5+ | 261 (0.8) | 649 (5.8) | |

| Infection | |||

| Infection (any) | 17,617 (55.1) | 8,659 (76.8) | |

| Sepsis | 2,851 (8.9) | 4,603 (40.8) | |

| Invasive fungal infection | 1,020 (3.2) | 799 (7.1) | |

| Pneumonia | 5,952 (18.6) | 4,479 (39.7) | |

| Urinary tract | 2,132 (6.7) | 1,082 (9.6) | |

| IV-line infection | 1,011 (3.2) | 487 (4.3) | |

| Inpatient Chemotherapy | 16,942 (53.0) | 6,205 (55.0) | |

Risk Factors for ICU Admission

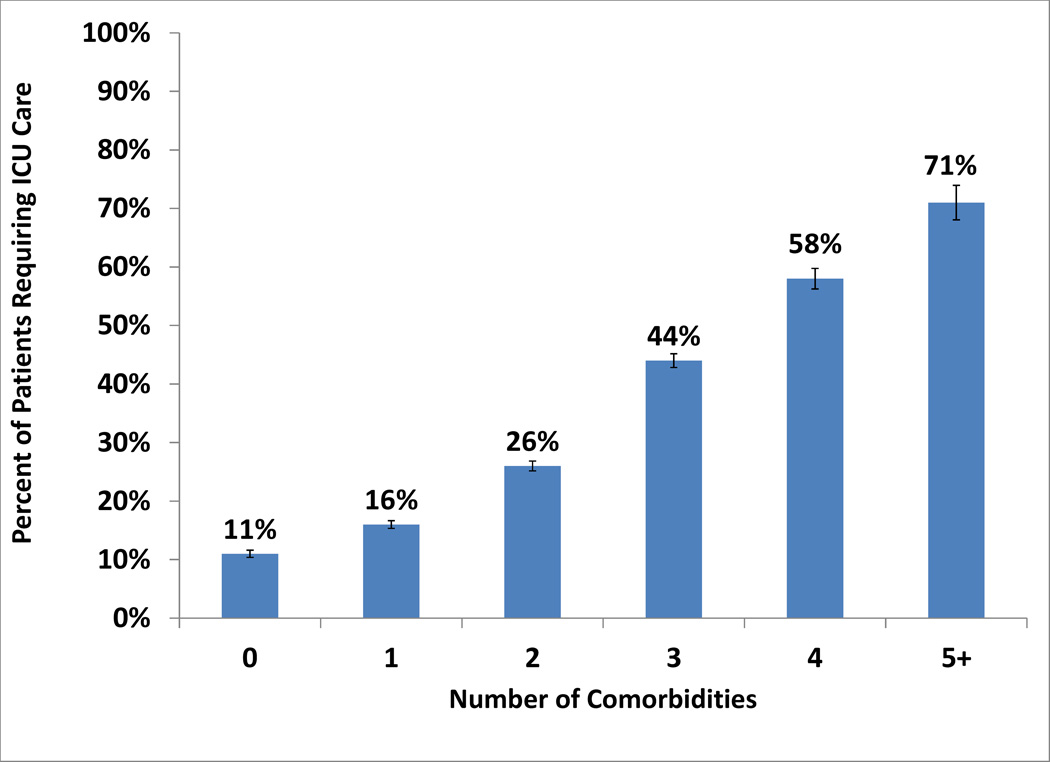

Risk factors for ICU admission in univariate analysis included age <80 years (OR=1.41, [95%CI: 1.3–1.53]), black race (OR=1.23 [1.15–1.32]), hospitalization in the South (OR=1.58 [1.50–1.66]), hospitalization at a small/medium-sized hospital (OR=1.17 [1.12–1.23]), ≥1 comorbidity (OR=3.58 [3.34–3.83]), sepsis (OR=7.13 [6.76–7.53]), pneumonia (OR=2.88 [2.75–3.02]), and invasive fungal infection (OR=2.32 [2.11–2.55]; all p<0.0001). Figure 1A depicts the relationship between comorbidity burden and ICU admission risk. Comorbidities that most affected risk of ICU admission included cerebrovascular, hepatic, and lung diseases (54.8%, 46.9%, and 46.5% of patients with each comorbidity admitted to the ICU). Receipt of inpatient chemotherapy had minimal effect on the risk of ICU admission: 26.8% of patients who received chemotherapy required ICU admission vs. 25.2% of those who did not. In multivariable analysis (Table 2), independent risk factors for ICU admission included age <80 years (OR= 1.56 [1.42–1.70]), hospitalization in the South (OR=1.81 [1.71–1.92]) or at a small/medium hospital (OR=1.25 [1.19–1.31]), ≥1 comorbidity (OR=10.64 [8.89–12.62] for 5 vs. 0 comorbidities), sepsis (OR=4.61 [4.34–4.89]), invasive fungal infection (OR=1.24 [1.11–1.39]) and pneumonia (OR= 1.73 [1.63–1.82]).

Figure 1.

A: Risk of ICU Admission by Number of Comorbidities

Bars represent 95% CIs

B: Mean Cost of Hospitalization by Number of Comorbidities

Bars represent 95% CIs

TABLE 2.

Multivariable Analysis for Risk of ICU Admission (n=43,249)

| Wald Confidence Interval | Robust Confidence Interval* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Age < 80 years | 1.56 | 1.42–1.70 | <.0001 | 1.36–1.78 | <.0001 | |

| Southern regions | 1.81 | 1.71–1.92 | <.0001 | 0.95–3.46 | 0.0704 | |

| Small or medium hospital | 1.25 | 1.19–1.31 | <.0001 | 0.76–2.04 | 0.3777 | |

|

Number of comorbidities (ref=none) |

||||||

| 1 vs. none | 1.47 | 1.35–1.59 | <.0001 | 1.24–1.74 | <.0001 | |

| 2 vs. none | 2.38 | 2.20–2.58 | <.0001 | 1.80–3.15 | <.0001 | |

| 3 vs. none | 4.35 | 3.99–4.73 | <.0001 | 3.05–6.19 | <.0001 | |

| 4 vs. none | 6.75 | 6.09–7.49 | <.0001 | 4.43–10.29 | <.0001 | |

| 5 vs. none | 10.64 | 8.98–12.62 | <.0001 | 6.96–16.27 | <.0001 | |

| Sepsis | 4.61 | 4.34–4.89 | <.0001 | 3.71–5.72 | <.0001 | |

| Invasive fungal infection | 1.24 | 1.11–1.39 | 0.0002 | 1.08–1.41 | 0.0018 | |

| Pneumonia | 1.73 | 1.63–1.82 | <.0001 | 1.55–1.92 | <.0001 | |

Adjusted for clustering of the observations from the same hospital

Risk Factors for Inpatient Mortality among Patients Requiring ICU Care

In-hospital mortality overall was 18.1%, but was significantly higher for ICU patients (43.1% vs. 9.3%, p<0.0001). Risk factors for in-hospital mortality in univariate analysis for patients admitted to the ICU included age ≥60 years (OR=1.41 [1.31–1.52]), non-white race (OR=1.23 [1.13–1.33]), hospitalization at a large hospital (OR=1.15 [1.06–1.24], p=0.0006), hospitalization on the West Coast (OR=1.30 [1.17–1.44]), sepsis (OR=4.19 [3.87–4.54]), pneumonia (OR=1.85 [1.72–2.00]), and invasive fungal infection (OR=1.74 [1.50–2.01]; all p<0.0001 unless stated). The number of major comorbid conditions for ICU patients was also highly associated with mortality risk. Specifically, for patients requiring ICU care, 5.7% of patients without any comorbidities died while inpatient, whereas this proportion increased to 21.2% for patients with one comorbidity and 66.6% if ≥5 comorbidities were present (p<0.0001 for trend). Not all comorbid conditions were equally associated with mortality, with the highest risk noted for cerebrovascular and hepatic disease (64.0% and 63.5% mortality, respectively). Infection was an important contributor to risk, and high mortality rates were found in ICU patients with sepsis (63.3%), invasive fungal infections (55.8%), and pneumonia (52.2%). Independent risk factors for mortality in ICU patients in multivariable analysis were: age ≥60 years (OR=1.16 [1.06–1.26]), non-white ethnicity (OR=1.18 [1.07–1.30]), hospitalization on the West Coast (OR=1.19 [1.06–1.34]), number of comorbidities (OR=18.76 [13.7–25.67] for 5 vs. 0 comorbidities), sepsis (OR=2.94 [2.70–3.21]), invasive fungal infection (OR=1.20 [1.02–1.42]), and pneumonia (OR= 1.13 [1.04–1.24]; Table 3, including p-values).

TABLE 3.

Multivariable Analysis for In-Hospital Mortality for ICU Patients (n=11,277)

| Wald Confidence Interval | Robust Confidence Interval* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Age ≥ 60 years | 1.16 | 1.06–1.26 | 0.0010 | 1.05–1.27 | 0.0024 | |

| Non-white ethnicity | 1.18 | 1.07–1.30 | 0.0006 | 1.05–1.32 | 0.0040 | |

| West Coast | 1.19 | 1.06–1.34 | 0.0039 | 0.99–1.43 | 0.0668 | |

|

Number of comorbidities (ref=none) |

||||||

| 1 vs. none | 3.95 | 2.98–5.25 | <.0001 | 3.00–5.20 | <.0001 | |

| 2 vs. none | 7.87 | 5.98–10.35 | <.0001 | 5.75–10.77 | <.0001 | |

| 3 vs. none | 15.02 | 11.43–19.74 | <.0001 | 10.43–21.67 | <.0001 | |

| 4 vs. none | 20.68 | 15.59–27.44 | <.0001 | 14.35–29.86 | <.0001 | |

| 5 vs. none | 18.76 | 13.7–25.67 | <.0001 | 12.54–28.11 | <.0001 | |

| Sepsis | 2.94 | 2.70–3.21 | <.0001 | 2.49–3.47 | <.0001 | |

| Invasive fungal infection | 1.20 | 1.02–1.42 | 0.0276 | 1.04–1.39 | 0.0103 | |

| Pneumonia | 1.13 | 1.04–1.24 | 0.0059 | 1.02–1.25 | 0.0183 | |

Adjusted for clustering of the observations from the same hospital

LOS and Cost

The mean (median) LOS for non-ICU patients was 15.3 (8) days compared with 22.4 (18) days for ICU patients. Other factors associated with prolonged hospitalization in univariate analysis (Table 4) included age, geographic region, hospital size, infection, and comorbid conditions. For example, the LOS for those requiring ICU admission was longest at larger volume hospitals (23.8 [20] vs. 19.4 [13] days for smaller hospitals; p<0.0001). LOS was longest on the West Coast at 25.3 (21) days compared with 22.0 (17) days for other regions (p<0.0001).

TABLE 4.

Cost and Length of Stay for Patients Requiring ICU Care (n=11,277)

| Total cost, 2014 dollars |

Length of Stay, days |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (median) | Mean (median) | ||

| ALL ICU Patients | 83,354 (61,172) | 22.4 (18) | |

| Geographic region | |||

| NorthEast | 79,045 (62,054) | 22.4 (18) | |

| Central | 85,763 (65,555) | 22.1 (18) | |

| West Coast | 108,918 (80,586) | 25.3 (21) | |

| Southern | 72,588 (49,214) | 21.3 (16) | |

| Hospital Size | |||

| Small | 67,195 (42,021) | 19.4 (13) | |

| Medium | 78,976 (60,050) | 22.4 (18) | |

| Large | 96,979 (72,468) | 23.8 (20) | |

| Year | |||

| 2004–2006 | 79,875 (56,206)) | 22.5 (18) | |

| 2007–2009 | 82,793 (61,960) | 22.0 (18) | |

| 2010–2012 | 86,030 (63,677) | 22.6 (18) | |

| Number of comorbidities | |||

| 0 | 50,543 (33,408) | 17.9 (12) | |

| 1 | 66,067 (46,486) | 20.2 (16) | |

| 2 | 78,172 (56,560) | 21.9 (17) | |

| 3 | 90,530 (69,029) | 23.2 (19) | |

| 4 | 103,289 (80,609) | 24.6 (20) | |

| 5+ | 124,820 (99,292) | 28.3 (22) | |

| Infection | |||

| Infection (any) | 96,380 (76,522) | 25.4 (22) | |

| Sepsis | 106,750 (84,080) | 26.4 (22) | |

| Invasive fungal infection | 150,413 (126,415) | 36.3 (33) | |

| Pneumonia | 107,399 (86,190) | 27.0 (23) | |

| Urinary tract | 114,869 (87,170) | 31.0 (26) | |

| IV-line infection | 127,691 (104,302) | 34.6 (31) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Lung disease | 97,976 (76,129) | 24.3 (20) | |

| Hepatic disease | 112,658 (87,530) | 26.5 (22) | |

| Renal disease | 97,284 (75,539) | 24.1 (20) | |

| Pulmonary embolism | 103,927 (84,287) | 26.8 (21) | |

| Venous thrombosis | 127,940 (104,979) | 33.0 (30) | |

The mean (median) total hospitalization cost for the entire patient cohort was $52,833 ($29,487). These cost estimates were significantly higher for ICU patients than non-ICU patients ($83,354 [$61,172] vs. $41,973 [$21,751], p<0.0001). For patients admitted to the ICU, costs varied considerably by demographic and clinical variables (Table 4) with highest costs for high-volume hospitals vs. low-volume hospitals ($96,979 [$72,468] vs. $67,195 [$42,021], p=0.0001 for trend). Comorbidities also had a significant impact on cost (Figure 1B). ICU patients without comorbidities had hospitalization costs of $50,543 ($33,408), increasing to $124,820 ($99,292) for those with ≥5 comorbidities (p<0.0001 for trend). Among ICU patients with infections, those with invasive fungal ($150,413 [$126, 415]) and catheter-associated infections ($127,691 [$104, 302]) incurred the highest costs. Geography also significantly affected cost for ICU patients, with total hospitalization costs highest on the West Coast ($108,918 [$80, 586]) and lowest in the South ($72,588 [$49,214], p<0.0001). Finally, 765 patients requiring ICU admission were eventually discharged to hospice. Hospitalization cost for patients transferred to hospice was slightly lower than for the other patients: ($78,070 [$48,994] vs. $83,740 [$61,942]; p=0.01).

Trends over Time

Admission rates to the ICU decreased slightly from 26.2% in 2004 to 23.3% in 2012 (p<0.0001 for trend). While in-hospital mortality decreased over time for the whole patient cohort (19.5% in 2004 to 14.5% in 2012, p<0.0001), this decrease was driven by those not requiring ICU care (12.4% in 2004 to 6.8% in 2012, p<0.0001). In contrast, in-hospital mortality for ICU patients remained relatively constant over the observation period (39.4% in 2004 vs. 39.8% in 2012, p=0.44 for trend). Mean total LOS remained unchanged for those not admitted (16.0 days in 2004 to 15.9 days in 2012, trend p=0.80) and those admitted to the ICU (23.2 days in 2004 vs. 23.2 days in 2012, trend p=0.27). Mean ICU days, however, decreased from 11.0 to 7.8 days between 2004 and 2012 (p<0.0001). Despite slightly decreased rates of ICU admission, decreased ICU LOS, and no change in overall LOS, costs after adjustment for inflation rose for both non-ICU and ICU patients, although more notably for ICU patients ($83,771 in 2004 to $89,673 in 2012, p<0.0001 for trend).

DISCUSSION

Treatment-related mortality (TRM) in AML has decreased over the last two decades.2,20 Consistent with this, we found a decrease in mortality over the study period in our patient cohort. However, this decrease was almost entirely driven by reduced early mortality in patients not requiring ICU care, whereas ICU admission rates have only slightly decreased and ICU stays remained associated with persistently high mortality and rising costs over the last decade.

While models are available to estimate the risk of TRM after initial intensive chemotherapy for newly-diagnosed AML21 or for patients undergoing HCT,22 no tools exist to reliably recognize those at risk for ICU admission and subsequent short-term mortality. Here, we identify demographic variables, systemic factors, and potentially modifiable medical characteristics (e.g. comorbidities and infections) associated with ICU admission, in-hospital mortality, and resource use in AML patients. These findings could spawn the development of prediction models for ICU use and outcome, which might provide a tool for risk-stratification, facilitate patient counseling, and could ultimately lead to new primary prevention and intervention strategies aimed at decreasing morbidity and mortality. Through targeting of modifiable risk factors, such strategies may be useful for improving patient outcomes.

ICU use and cost have risen in the U.S. since the 1990s, and critical care services now represent a higher-than-ever proportion of the gross domestic product.23 Consistent with this trend, cost estimates in our analysis were more than double for AML patients requiring ICU admission compared to those who did not, and increased over time despite stable mortality rates, stable total hospital LOS, and decreased ICU LOS. The specific reasons for this disproportionate rise in cost remain unknown as detailed epidemiologic data encompassing the hospital care and resource utilization of AML patients are lacking,24 but are likely interrelated with the increase in healthcare costs in general and in cancer care and ICU costs in particular.25 These costs are fueled by increasingly expensive therapies as well as expansion in the extent of care offered and the use and availability of technology in the oncology and critical care settings.26 An important step in addressing this rise in cancer costs includes the identification of contributing, modifiable factors as revealed in our study. This knowledge provides the basis for future investigations on how these risk factors could be mitigated to reduce ICU use in AML patients.

Another factor contributing to high costs are readmissions27, which are common in AML for both disease and treatment-related complications. Notably, 47.3% of the patients in our database had only a single admission. In analyzing this subgroup, we found a variety of potential contributing factors including death on this first admission (13.4%) as well as a higher rate of single admissions in the final year of the study period. Further, these patients were more likely to be admitted to smaller hospitals, and thus possibly transferred to tertiary care center not in the consortium for further care, and were older, and therefore potentially less likely to be treated and readmitted for complications. An upcoming study will examine risk factors for readmissions in AML.

Recent evidence has demonstrated that hospital size can affect mortality of patients undergoing surgical or medical cancer treatments.28 For AML, previous studies indicated that mortality rates while undergoing chemotherapy are lower in high-volume vs. low-volume centers despite similar mean LOS and cost.29 In this study, we found that hospital size was not independently associated with mortality in AML patients requiring ICU care, but that mean LOS and costs were significantly higher at high-volume hospitals. Referral bias of sicker patients to larger hospitals, and increased availability, and therefore use of, resources in larger hospitals may partly explain this observation - a notion supported by data indicating that ICU bed supply increases ICU bed utilization and healthcare spending, even after controlling for severity of illness.30 This difference may account for greater spending on critical care services in the U.S. compared to other countries30 and offers a rational target for intervention.

The use of a pre-existing database offers several advantages, including the economy of data on a large scale and a large sample size, aspects uncommon to AML studies. Additionally, as many recommendations for AML management are based on findings from selected study patients that may not be applicable to the general AML population,31,32 the use of “real-world” patient data may provide more generalizable insight. Additionally, by inclusion of diverse hospitals across the U.S., our approach removes the population bias of single-center studies. Still, a retrospective database analysis has several inherent limitations. First and foremost, the UHC database relies on administrative coding and only captures hospital-based care. However, these limitations are unlikely to significantly affect our findings, as coding for AML and comorbidities has been validated in prior reports and found to be accurate,33,34 and the vast majority of resource-intense care management of AML remains hospital-based. Additionally, depending on the coder, some patients in “remission” but receiving consolidation therapy for their disease likely were included as having active AML, and inclusion of these “less sick” patients may have lowered our estimates of poor outcomes and resource use. Further, the variables available for analysis were predetermined and did not include data on disease characteristics (e.g. cytogenetic profile), treatment phase (induction vs. consolidation), response to therapy, reason for hospital and ICU admission, use of prophylactic antimicrobials, and cause of death. To address some of these limitations, we performed exploratory analyses investigating the impact of some of these factors by identifying patients with relapsed disease and those with a concurrent diagnosis of MDS, potentially a surrogate for AML with an antecedent hematologic disorder. While patients with relapsed AML had a slightly lower risk of ICU admission than other patients, which remained significant in multivariate analysis (23.4% vs. 26.3%; OR=0.73[0.67–0.80] p<0.0001), relapsed disease was not an independent predictor of mortality in multivariable analysis. Further, co-diagnosis of MDS did not independently impact risk of ICU admission or mortality in multivariable analysis. As another limitation, the random selection of one hospitalization for patients admitted more than once during the study period may lead to an underestimate of true resource use, as AML patients are often readmitted in short time spans for treatment-related complications such as neutropenic fever/infection or organ toxicities. Finally, the criteria for ICU admission vary between institutions, introducing heterogeneity into our study cohort. For example, admission of less sick patients to certain ICUs may affect mortality and resource utilization estimates, but would be expected to yield smaller, rather than larger, differences between patients requiring and not requiring ICU care.

In summary, our findings demonstrate that ICU care remains common in AML patients and is associated with substantial mortality and an increasing demand on healthcare resources over time. The identification of several factors that are significantly associated with ICU admission, mortality, and cost provide the basis for the development of tools for personalized, informed decisions in the management of AML that can assist in optimizing resource use for AML patients and improving treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: A.B.H. is supported by a fellowship training grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Institutes of Health (NHLBI/NIH: T32-HL007093). R.B.W. is a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Scholar in Clinical Research.

Role of Funder/Sponsor: There was no funder of this project. None of the below mentioned companies had any role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Authorship: A.B.H and R.B.W. were responsible for the conception and design of this article and contributed to the literature search, data analysis and interpretation, and wrote and critically revised the manuscript. G.H.L was responsible for conception and design, acquisition of data, data interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript. E.C contributed to the conception and design, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation, statistical analysis, drafting of the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors had final approval of the manuscript. A.B.H. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures: E.C. and G.H.L receive salary support from a research grant from Amgen for their institution. R.B.W. has a consulting/advisory role for Amphivena Therapeutics, Covagen AG, AstraZeneca, Seattle Genetics and Pfizer and receives research funding from Seattle Genetics, Amgen, Celator, CSL Behring, Seattle Genetics, Amphivena Therapeutics, and Abbvie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2012. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2015. [based on November 2014]. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/, SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Othus M, Kantarjian H, Petersdorf S, et al. Declining rates of treatment-related mortality in patients with newly diagnosed AML given 'intense' induction regimens: a report from SWOG and MD Anderson. Leukemia. 2014;28:289–292. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gooley TA, Chien JW, Pergam SA, et al. Reduced mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2091–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azoulay E, Alberti C, Bornstain C, et al. Improved survival in cancer patients requiring mechanical ventilatory support: impact of noninvasive mechanical ventilatory support. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:519–525. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200103000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilbert G, Gruson D, Vargas F, et al. Noninvasive ventilation in immunosuppressed patients with pulmonary infiltrates, fever, and acute respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:481–487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson K, Mollee P, Morris K, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors for patients with acute myeloid leukemia admitted to the intensive care unit. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:97–104. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.796045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roze des Ordons AL, Chan K, Mirza I, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with acute myelogenous leukemia admitted to intensive care: a case-control study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:516. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thakkar SG, Fu AZ, Sweetenham JW, et al. Survival and predictors of outcome in patients with acute leukemia admitted to the intensive care unit. Cancer. 2008;112:2233–2240. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schellongowski P, Staudinger T, Kundi M, et al. Prognostic factors for intensive care unit admission, intensive care outcome, and post-intensive care survival in patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: a single center experience. Haematologica. 2011;96:231–237. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.031583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keenan TLT, Traeger L, Vandusen H, Abel GA, Steensma DP, Fathi AT, DeAngelo DJ, Wadleigh M, Hobbs G, Amrein PC, Stone RM, Ballen KM, Chen Y, Temel JS, El-Jawahri A. Blood. Orlando, FL: 2015. Dec 5, Outcomes for Older Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bird GT, Farquhar-Smith P, Wigmore T, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors in patients with haematological malignancy admitted to a specialist cancer intensive care unit: a 5 yr study. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108:452–459. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeo CD, Kim JW, Kim SC, et al. Prognostic factors in critically ill patients with hematologic malignancies admitted to the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2012;27:739.e1–739.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabbat A, Chaoui D, Montani D, et al. Prognosis of patients with acute myeloid leukaemia admitted to intensive care. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:350–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Townsend WM, Holroyd A, Pearce R, et al. Improved intensive care unit survival for critically ill allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients following reduced intensity conditioning. Br J Haematol. 2013;161:578–586. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothen HU, Stricker K, Einfalt J, et al. Variability in outcome and resource use in intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1329–1336. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0690-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.UDAahwueAJ. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuderer NM, Dale DC, Crawford J, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and cost associated with febrile neutropenia in adult cancer patients. Cancer. 2006;106:2258–2266. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.BoLSAahwbgdichAJ. U.S. Department of Labor; [Google Scholar]

- 20.Percival ME, Tao L, Medeiros BC, et al. Improvements in the early death rate among 9380 patients with acute myeloid leukemia after initial therapy: A SEER database analysis. Cancer. 2015;121:2004–2012. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walter RB, Othus M, Borthakur G, et al. Prediction of early death after induction therapy for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia with pretreatment risk scores: a novel paradigm for treatment assignment. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4417–4423. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106:2912–2919. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical care medicine in the United States 2000–2005: an analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:65–71. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b090d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merz TM, Schar P, Buhlmann M, et al. Resource use and outcome in critically ill patients with hematological malignancy: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2008;12:R75. doi: 10.1186/cc6921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith TJ, Hillner BE. Bending the cost curve in cancer care. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2060–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1013826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramsey SD, Ganz PA, Shankaran V, et al. Addressing the American health-care cost crisis: role of the oncology community. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1777–1781. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hillner BE, Smith TJ, Desch CE. Hospital and physician volume or specialization and outcomes in cancer treatment: importance in quality of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2327–2340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.11.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giri S, Pathak R, Aryal MR, et al. Impact of hospital volume on outcomes of patients undergoing chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia: a matched cohort study. Blood. 2015;125:3359–3360. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-625764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gooch RA, Kahn JM. ICU bed supply, utilization, and health care spending: an example of demand elasticity. Jama. 2014;311:567–568. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.283800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostgard LSG, Nørgaard M, Sengeløv H, et al. Do Results From Clinical Trials in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Reflect Clinical Reality? A Danish National Cohort Study of 813 Patients. Blood. 2012;120:1477–1477. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hills RK, Burnett AK. Applicability of a "Pick a Winner" trial design to acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:2389–2394. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-337261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quan H, Parsons GA, Ghali WA. Validity of information on comorbidity derived rom ICD-9-CCM administrative data. Med Care. 2002;40:675–685. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sutton JM, Hayes AJ, Wilson GC, et al. Validation of the University HealthSystem Consortium administrative dataset: concordance and discordance with patient-level institutional data. J Surg Res. 2014;190:484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]