Abstract

Objective

To identify a core set of domains (outcomes) to be measured in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) clinical trials that represent both patients' and physicians' priorities.

Methods

We conducted (1) a systematic literature review (SLR) of domains assessed in PsA; (2) international focus groups to identify domains important to people with PsA; (3) two international surveys with patients and physicians to prioritise domains; (4) an international face-to-face meeting with patients and physicians using the nominal group technique method to agree on the most important domains; and (5) presentation and votes at the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) conference in May 2016. All phases were performed in collaboration with patient research partners.

Results

We identified 39 unique domains through the SLR (24 domains) and international focus groups (34 domains). 50 patients and 75 physicians rated domain importance. During the March 2016 consensus meeting, 12 patients and 12 physicians agreed on 10 candidate domains. Then, 49 patients and 71 physicians rated these domains' importance. Five were important to >70% of both groups: musculoskeletal disease activity, skin disease activity, structural damage, pain and physical function. Fatigue and participation were important to >70% of patients. Patient global and systemic inflammation were important to >70% of physicians. The updated PsA core domain set endorsed by 90% of OMERACT 2016 participants includes musculoskeletal disease activity, skin disease activity, pain, patient global, physical function, health-related quality of life, fatigue and systemic inflammation.

Conclusions

The updated PsA core domain set incorporates patients' and physicians' priorities and evolving PsA research. Next steps include identifying outcome measures that adequately assess these domains.

Keywords: Psoriatic Arthritis, Outcomes research, Qualitative research, Spondyloarthritis

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory disease with heterogeneous manifestations affecting the skin, nails, peripheral joints, spine and entheses. PsA can have a broad and profound impact on quality of life.1 2 However, PsA life impact is not fully assessed by the outcome measurement tools used in current randomised controlled trials (RCTs).3 Furthermore, most of these tools have been adapted from studies in rheumatoid arthritis and may not accurately reflect the whole experience of patients with PsA.4

A PsA core set of domains to be measured in PsA RCTs and longitudinal observational studies (LOS) was originally developed by the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) and endorsed by the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) in 2006.5 Since then, the science of outcomes research and our knowledge of PsA have both significantly evolved. First, the inclusion of patient research partners (PRPs) and other relevant stakeholders is now highly recommended in all stages of the research process by both OMERACT6 and the European League Against Rheumatism 7 as well as regulatory agencies in the USA and Europe. Additionally, OMERACT has updated its recommendations for developing disease core sets and published a core set development process map, the OMERACT Filter 2.0,6 which was endorsed in 2014. Concurrently, along with methodological developments, there has been much progress in PsA treatment with three new classes of targeted therapeutics approved in the past three years.8 9 Recent PsA RCTs assessed therapeutic efficacy not only by traditional outcomes centred on peripheral arthritis, but also additional measures of PsA manifestations (eg, systemic inflammation, enthesitis, dactylitis, structural damage, nail disease and the spine) and life impact (eg, fatigue, productivity).10 These were considered important in the 2006 PsA core domain set but not essential to measure in all RCTs either due to insufficient data to support measurement or due to the absence of validated outcome measures.5 11

The objective of the GRAPPA-OMERACT PsA working group was to develop consensus, at an international level, among patients and physicians on a core set of domains to be measured in PsA RCTs and LOS. Based on the methodological framework of OMERACT Filter 2.0,6 we designed research work streams to generate patient-relevant and physician-relevant domains and then arrive at consensus on PsA domains reflective of stakeholder perspectives.

Methods

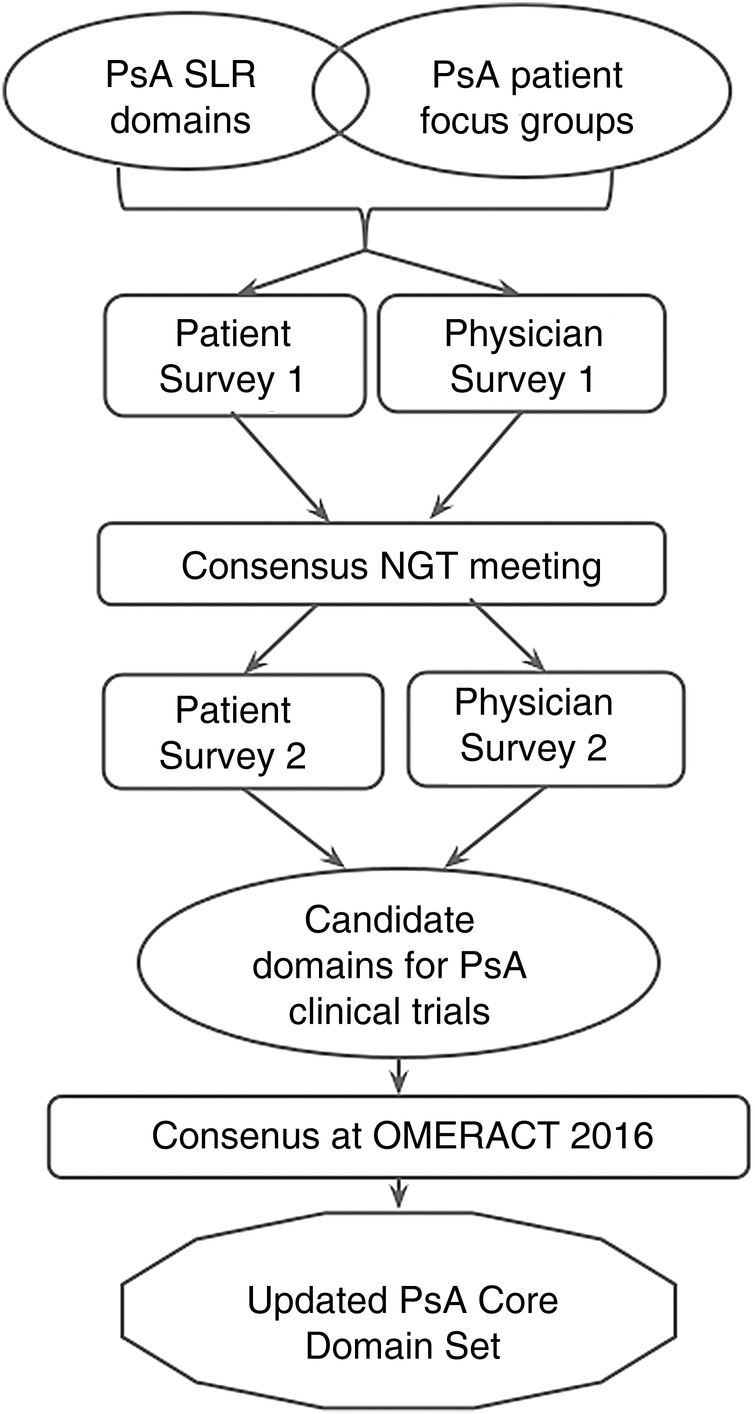

We conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) of domains assessed in PsA RCTs, LOS and registries, international qualitative focus groups, two international web-based surveys with patients and physicians, and an international face-to-face consensus meeting with patients and physicians using the nominal group technique (NGT) to agree on domains most important to all participants. PRPs were included in all phases of the process.12 Results were presented at the OMERACT conference in May 2016 in British Columbia, Canada and discussed in a plenary workshop and small groups. A diagram of the research process is represented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study diagram: research work streams that led to the updated psoriatic arthritis (PsA) core domain set are represented: the process started with a systematic literature review (SLR) and international focus groups with patients with PsA to generate a large pool of candidate domains. These were then reduced through an iterative consensus process consisting of surveys with patients and physicians, a consensus nominal group technique (NGT) meeting with patients and physicians, and breakout group discussions and voting at the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) 2016.

Systematic literature review

An SLR was performed to identify all domains (or outcomes) measured in PsA RCTs, LOS and registries from 2010 to 2015.10 A previous SLR reviewed the PsA outcomes used in the previous 5-year interval.13

International focus groups

Focus groups were conducted to identify domains important to patients with PsA.14 Two qualitative research studies were conducted independently and in parallel with patients with PsA to identify outcomes important to them: a focus group study across six countries (Australia, Brazil, France, Netherlands, Singapore, the USA); and a multicentre UK focus group study. Participants met Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis15 and were sampled across the spectrum of PsA manifestations, activity and demographic characteristics. After informed consent was obtained, qualified facilitators (two per group) led a semistructured discussion following a focus group guide agreed upon by the investigators in advance. Each focus group was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were immediately translated into English and proofread with a native speaker to assist in translation as needed.16 Investigators on both teams included PRPs in study conception, conduct and data analysis. Qualitative data analysis was completed independently by each team using inductive thematic analysis17 to identify domains and domain definitions based on focus group participants' descriptions.

International surveys among patients and physicians

Domains from the focus group studies and the SLR were combined into a single list of domains. Definitions were assembled using focus group participants' descriptions and reviewed by the working group including PRPs to ensure that patient participants would easily understand domains. Web-based surveys were then administered to patients and physicians (separate surveys running in parallel) to rate domains for importance. Patient participants were recruited from clinics at five sites and PsA patient organisations. Patients were purposefully selected to represent all phenotypes of PsA including varied levels of skin disease, joint disease, disease manifestations, age and gender. Physician participants were purposefully selected from GRAPPA members to include both rheumatologists and dermatologists, representative of different parts of the world, age and gender groups. Patient surveys were administered in English, except to French patient participants who received the survey translated in French. REDCap (V.6.13.3) software18 was used for survey administration, data collection and management. Participants received an introduction about the project objectives and were asked to rate each domain on an 11-point numerical rating scale from 0, ‘not important at all’, to 10, ‘very important’. Survey results for the patient and physician groups were separately summarised as mean, median and percentage of respondents who rated each domain in one of three categories of importance (≤3, 4–7 and ≥8). Each domain was then assigned to one of three categories reflecting levels of agreement: (A) important for both groups (>50% in each group voted the domain as ≥8); (B) important for one group but not for the other group (>50% voted the domain as ≥8 in one group and >50% voted the domain as <8 in the other); and (C) less important for both groups (>50% in both groups voted the domain as <8).

Face-to-face consensus meeting

In total, 12 patients, 12 physicians and 2 non-voting fellows were invited to participate in a face-to-face consensus meeting held on 12 March 2016 in Jersey City, New Jersey, USA. An independent expert in consensus methods (JAS) moderated the meeting using the NGT. The NGT is a rigorously structured meeting conducted to allow a group of key stakeholders to identify and rate a list of priorities while ensuring the inclusion of all participants' opinions.19 The objective of the meeting was to agree on a preliminary core set of the 7–10 most important domains for both patients and physicians to be measured in PsA RCTs and LOS. The goal number of domains was established a priori after considering feasibility and other examples of disease core sets.20

For patients, a separate introduction was held the evening before the meeting to familiarise them with the objectives, and the consensus process as well as domains and definitions. The consensus meeting began with an introduction to OMERACT Filter 2.0 and presentation of results from the research work streams. Participants were informed that according to the methodological framework used (OMERACT Filter 2.0) the availability and applicability of outcome measurement instruments were not relevant to the domain discussion and this was reinforced throughout the meeting. The NGT process started with discussion of domains that were in category C (described above) with the purpose to discard them or move them into category B. Next items were moved from category B into category A or discarded. Then, the remaining items were discussed and maintained or merged into larger categories if agreed on by most participants to help reduce the number of domains. Anonymised votes on agreement with domain placement were conducted as needed on coloured index cards to distinguish patients and physicians and allow reporting of results by group and not by majority alone. At the end of the meeting, a preliminary core set of domains for PsA was drafted and presented to the group.

Second international surveys with patients and physicians

Following the consensus meeting, a second round of web-based surveys was conducted among the same patients and physicians who were invited to participate in the first survey. Participants were asked to rate the importance of each domain in the preliminary PsA core domain set using the same 11-point numerical rating. Results of the survey reported for patients and physicians separately as mean, median and percentage of respondents rating items as important (defined as score ≥8).

OMERACT endorsement

The PsA Workshop was held at the 2016 OMERACT Conference in Whistler, British Columbia, Canada.21 The work above was presented, breakout groups discussed the domains proposed, and finally, OMERACT participants voted for individual domains as well as the final core domain set (Orbai AM, de Wit M, Mease PJ, et al. Updating the psoriatic arthritic core domain set: a report from the PsA workshop at OMERACT 2016. The J Rheumatol 2016 (submitted)).

Results

Candidate domains

Twenty-four domains were obtained from the SLR of outcomes measured in PsA RCTs, LOS and registries. Measurement of the complete 2006 PsA core domain set increased in RCTs conducted 2010–2015 compared with 2006–2010. Recent RCTs frequently measured domains in addition to the core set; and among RCTs, there was great heterogeneity in outcome measure selection per domain.

The focus group study consisted of 16 focus groups with 89 participants with PsA on five continents represented by six countries (number of focus groups in each country): the USA (5), Brazil (3), Australia (2), France (2), the Netherlands (2) and Singapore (2). The UK focus group study consisted of eight focus groups with 41 participants. Thirty-five domains and corresponding definitions were obtained from qualitative data analysis of international PsA focus group transcripts.

Combining domains from the SLR and focus group studies resulted in a list of 39 unique domains (table 1). The domains and definitions were reviewed for clarity by the working group (seven physicians, five PRPs, two fellows and one methodologist).

Table 1.

Candidate psoriatic arthritis domains and definitions

| Domain | Definition* | |

| 1 | Anxiety | Being concerned, worried, fearful or anxious |

| 2 | Cognitive function | Being able to concentrate and remember things (concentration and memory issues) |

| 3 | Coping | Being able to deal with the social and emotional impact of the disease on oneself (includes managing stress, embarrassment) |

| 4 | Daily activities including housework | Being able to fulfil housework tasks, shopping, other necessary daily activities |

| 5 | Dactylitis | Sausage finger or toe, full thickness inflammation of a digit or toe |

| 6 | Depressive mood | Feeling sad, feeling down or sorry for oneself or feeling depressed |

| 7 | Discomfort | Experiencing noticeable physical issues/discomfort, which are not pleasant but not causing pain |

| 8 | Disease activity | Presence of disease symptoms |

| 9 | Embarrassment | Experiencing awkward self-consciousness or embarrassment in public or social situations |

| 10 | Emotional support | Availability of emotional support from family members and friends |

| 11 | Emotional well-being | Feeling good about oneself |

| 12 | Employment/work | Being able to perform activities related to work/employment |

| 13 | Enthesitis | Pain and inflammation at the site of a tendon bone interface (tendon insertions on bone) |

| 14 | Family roles | Relationships with family and close friendships (includes parenthood, marriage) |

| 15 | Fatigue | Experiencing fatigue, tiredness, lack of energy, feeling worn out or exhausted |

| 16 | Financial impact | Experiencing financial loss due to treatment cost, work loss, early retirement, cost of assistive devices, etc |

| 17 | Frustration | Being annoyed or upset about not being able to achieve what one wishes |

| 18 | Global health | The overall health status of the patient |

| 19 | Independence | Being able to maintain one's independence, not being dependent on others for help |

| 20 | Intimacy and sexual relations | Satisfaction with intimate relationships |

| 21 | Leisure activities | Being able to engage in leisure activities |

| 22 | Medication side effects | Experiencing undesired secondary effects from taking psoriatic arthritis medications |

| 23 | Nail psoriasis | Having discoloured, lifting, pitted nails affected with psoriasis |

| 24 | Pain | Experiencing an unpleasant physical sensation that aches, hurts in one or more joints or the spine |

| 25 | Participation in social activities | Ability to participate in social activities |

| 26 | Structural joint damage | Join deformity, damage, instability to one or more joints or the spine |

| 27 | Physical function | Being able to perform physical activities (includes upper/lower extremity functioning, balance) |

| 28 | Psoriasis symptoms | Experiencing itching, dryness, pain, plaques, thickness, cracks, bleeding, scaling of affected skin including genital areas and the scalp |

| 29 | Self-management | Being able to effectively decrease or minimise the physical impact of disease on oneself (eg, choice of non-pharmacological interventions, prevention of disease worsening, use of aids, diet, lifestyle, pacing, relaxation etc) |

| 30 | Self-worth | Shame, self-esteem, feeling accepted or rejected by others (can range from feeling valued to feeling helpless, useless, ashamed, guilty or rejected) |

| 31 | Sleep quality | Being able to have a restful sleep |

| 32 | Social support | Availability of family members and friends for help |

| 33 | Spine symptoms | Back/spine symptoms of pain, stiffness |

| 34 | Stiffness | Experiencing resistance or rigidity in one or more joints, tendons or the spine, which prevents smooth and full range of motion |

| 35 | Stress | Feeling under pressure and under tension |

| 36 | Swelling | Enlargement of one or more joints |

| 37 | Systemic inflammation | Blood test such as the acute-phase reactants ESR and/or C reactive protein |

| 38 | Treatment burden | Impact of treatment and monitoring of disease or treatment (eg, financial or time commitment) |

| 39 | Unpredictability of disease activity | Uncertainty in the short term of being symptom free or able to engage in activities |

Domains appear in alphabetical order.

*Domain definitions represent focus group participants’ descriptions of the corresponding domain and were reviewed by the working group. ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

International patient and physician survey results

The survey was administered to 100 patients and 124 physicians. In total, 50 patients (50%) and 75 physicians (60%) completed the survey. Patient respondents were 64% female and age groups (years) 2% (18–25), 36% (26–45), 52% (46–65) and 10% above 65. Physician respondents were 92% rheumatologists and 8% dermatologists, 61% male, and age groups (years) 33% (26–45), 60% (46–65) and 7% (above 65). Results are summarised in table 2 for each of the 39 domains. Based on percentage votes into each category of importance, domains were organised into agreement categories A, B or C ((A) important for both groups (>50% in each group voted the domain as ≥8); (B) important for one group but not for the other group (>50% voted the domain as ≥8 in one group and >50% voted the domain as <8 in the other); and (C) less important for both groups (>50% in both groups voted the domain as <8)).

Table 2.

Domain ratings by patients and physicians and corresponding agreement categories in the first survey

| Ratings | Patients, N=50 |

Physicians, N=75 |

Category* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤3 | 4–7 | ≥8 | ≤3 | 4–7 | ≥8 | ||

| Domains and corresponding group % for each category of ratings | |||||||

| Anxiety | 30 | 40 | 30 | 41 | 41 | 17 | C |

| Cognitive function | 30 | 28 | 42 | 41 | 47 | 12 | C |

| Coping | 16 | 42 | 44 | 28 | 36 | 36 | C |

| Daily activities including housework | 10 | 18 | 72 | 1 | 35 | 64 | A |

| Dactylitis | 18 | 22 | 60 | 3 | 13 | 84 | A |

| Depressive mood | 16 | 38 | 44 | 17 | 51 | 32 | C |

| Discomfort | 12 | 40 | 48 | 16 | 52 | 32 | C |

| Disease activity | 4 | 32 | 64 | 1 | 16 | 83 | A |

| Embarrassment | 30 | 42 | 28 | 24 | 45 | 31 | C |

| Emotional support | 22 | 30 | 48 | 33 | 52 | 15 | B |

| Emotional well-being | 10 | 30 | 60 | 24 | 48 | 28 | B |

| Employment/work | 4 | 20 | 76 | 3 | 21 | 76 | A |

| Enthesitis | 8 | 26 | 66 | 0 | 16 | 84 | A |

| Family roles | 12 | 32 | 56 | 25 | 53 | 21 | B |

| Fatigue | 0 | 22 | 78 | 4 | 33 | 63 | A |

| Financial impact | 20 | 32 | 48 | 23 | 43 | 35 | C |

| Frustration | 18 | 36 | 46 | 33 | 45 | 21 | C |

| Global health | 8 | 24 | 68 | 5 | 24 | 71 | A |

| Independence | 8 | 10 | 82 | 20 | 42 | 37 | B |

| Intimacy and sexual relations | 24 | 34 | 42 | 24 | 47 | 29 | C |

| Leisure activities | 2 | 38 | 60 | 11 | 61 | 28 | B |

| Medication side effects | 4 | 26 | 70 | 11 | 24 | 65 | A |

| Nail psoriasis | 22 | 34 | 44 | 8 | 25 | 67 | B |

| Pain | 4 | 20 | 76 | 1 | 11 | 88 | A |

| Participation in social activities | 6 | 38 | 56 | 12 | 52 | 36 | B |

| Physical function | 4 | 24 | 72 | 0 | 17 | 83 | A |

| Psoriasis symptoms | 10 | 32 | 58 | 1 | 17 | 81 | A |

| Self-management | 4 | 38 | 58 | 17 | 52 | 31 | B |

| Self-worth | 22 | 40 | 38 | 32 | 40 | 28 | C |

| Sleep quality | 8 | 26 | 66 | 12 | 49 | 39 | B |

| Social support | 16 | 48 | 36 | 31 | 57 | 12 | C |

| Spine symptoms | 14 | 22 | 64 | 1 | 21 | 77 | A |

| Stiffness | 2 | 32 | 66 | 1 | 36 | 63 | A |

| Stress | 14 | 36 | 50 | 32 | 52 | 16 | B |

| Structural joint damage | 8 | 24 | 68 | 1 | 21 | 77 | A |

| Swelling | 14 | 22 | 64 | 4 | 13 | 83 | A |

| Systemic inflammation | 22 | 34 | 44 | 8 | 23 | 69 | B |

| Treatment burden | 6 | 48 | 46 | 19 | 55 | 27 | C |

| Unpredictability of disease activity | 10 | 36 | 54 | 31 | 44 | 25 | B |

Light grey cells were rated by >50% of participants. Darker grey cells with bolded font were rated as important by ≥70% of participants.

*Categories were defined as (A) important for both groups (>50% in each group voted the domain as ≥8); (B) important for one group but not for the other group (>50% voted the domain as ≥8 in one group and >50% voted the domain as <8 in the other); (C) less important for both groups (>50% in both groups voted the domain as <8).

Consensus meeting summary

During the NGT process, participants regrouped or redefined some items from the list of 39 domains. For example, emotional well-being captures depressive mood, anxiety, embarrassment, self-worth, frustration and stress. Participation includes family roles, social activities, leisure activities and employment. As part of the discussion related to combining these elements, participants referred to the International Classification of Functioning (ICF) distinction between activity and participation. In the ICF, ‘activities’ encapsulates the ability to perform a task or action by an individual; ‘participation’ is the ability to be involved in life, to perform societal tasks and responsibilities, to work, to take part in social events, leisure and family life.22 The musculoskeletal (MSK) manifestations of PsA (peripheral joint activity, dactylitis, enthesitis and spondylitis) were grouped under the larger concept of MSK disease activity. Similarly, skin activity was defined as including both skin and nail disease.

The concept of health-related quality of life (HRQoL), present in the 2006 PsA core domain set and potentially overlapping with some of these domains, was brought up for discussion. Participants agreed that aspects of physical, emotional and social life are included in HRQoL. However, patients unanimously favoured the inclusion of specific domains in the core set (emotional well-being, fatigue, pain, participation, physical function) over the broad concept of HRQoL. The patient global assessment of disease was also discussed. While there was general agreement to not discuss instruments, little is understood about what the ‘patient global assessment’ measures are. The concept was felt to reflect disease activity but also an overarching global health status of the patient, specific to that patient. As a result of this discussion, global health was renamed patient global defined as patient global assessment of disease-related health status and maintained as a core domain.

Structural joint damage was voted important by both groups. However, in the meeting, there was a debate whether or not it should be required in all RCTs and LOS or designated as important but not required for each clinical trial. Discussions were focused on three main points: (1) one of the main objectives of disease-modifying therapy in PsA is to ultimately prevent structural damage and not only symptoms; (2) the use of current imaging procedures, especially more sensitive ones like MRI, is costly; and (3) it is difficult to demonstrate a significant difference in structural damage in RCTs of short duration. The final decision was to include structural damage with the specification that evidence for inhibition of structural damage should be required at least once during the development programme of a new medication but not required in all RCTs and LOS.

At the end of the consensus meeting, 10 domains were agreed on as important and proposed for inclusion in the PsA core domain set for clinical trials: MSK disease activity, skin disease activity, pain, patient global, physical function, participation, emotional well-being, fatigue, systemic inflammation and structural damage (with the specification that this is recommended for inclusion at least once during a PsA drug development programme). Economic cost was recommended as important but not essential to be measured in all clinical trials. Items placed on the PsA group research agenda due to their importance to patients but unclear contribution to measuring response in RCTs and LOS were independence, sleep, stiffness and treatment burden. Specific details on each domain discussion and their movement among categories during the consensus meeting are provided in online supplementary table S1. The preliminary PsA domain structure at the conclusion of the consensus meeting is represented in online supplementary figure S1.

Domain discussion and assignment to core, outer circle, research agenda, contextual factors or adverse events during the nominal group technique consensus meeting with patients and physicians

annrheumdis-2016-210242supp001.pdf (116.1KB, pdf)

Proposed updated psoriatic arthritis core domain set at the conclusion of the nominal group technique meeting with patients and physicians: MSK (musculoskeletal) disease activity includes peripheral joints, enthesitis, dactylitis and spondylitis; skin activity includes skin and nails; patient global is defined as patient reported disease related health status; participation (e.g. family roles, social, leisure, work/employment); emotional well-being (e.g. depressive mood, anxiety, embarrassment, selfworth, frustration, stress); structural damage* should be measured at least once during a drug development program for PsA;

annrheumdis-2016-210242supp002.pdf (129.9KB, pdf)

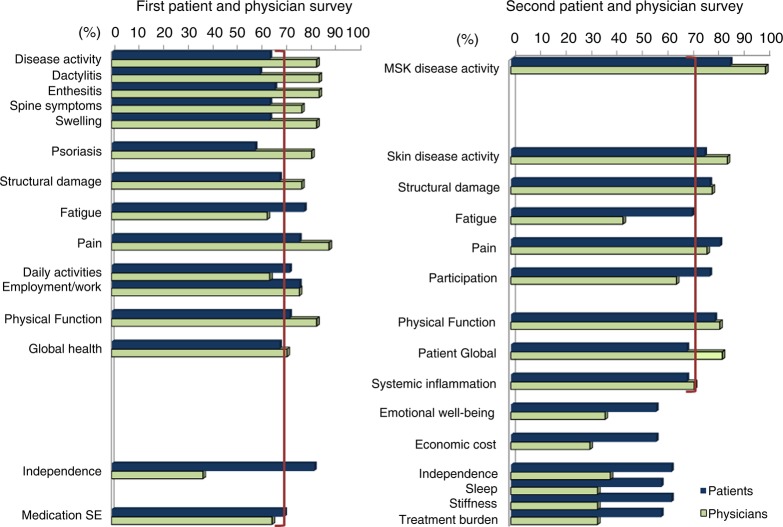

Second international patient and physician survey

A second survey was administered to 100 patients and 124 physicians to rate the importance of each domain agreed on in the consensus meeting. In total, 49 patients (49%) and 71 physicians (57%) completed the survey. Results are summarised in online supplementary table S2. Survey respondents agreed with the proposed core domain set drafted at the consensus meeting, with the exception of emotional well-being, which was rated important by <70% of both patients and physicians in the second survey. Figure 2 summarises results from both survey rounds.

Figure 2.

Domains important to patients and physicians for inclusion in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) clinical trials: The first panel shows domains selected important* by >70% of either patients or physicians in the first international survey and patient and physician percentages. The second panel shows patient and physician percentages rating each domain as important* in the second international survey (*important was designated as receiving a rating of ≥8 on a numerical rating scale from 0, not important at all, to 10, very important). The brackets identify the 70% level of consensus within a group. MSK, musculoskeletal.

Endorsement of the PsA core domain set

Based on discussions and voting at the biannual OMERACT meeting (2016), participation and structural damage in the preliminary core set were moved to the middle circle (strongly recommended but not mandatory for all RCTs and LOS). The updated 2016 PsA domain set achieved consensus with a 90% vote from 130 OMERACT participants. The 2016 PsA core domain set includes the following outcomes recommended for assessment in all RCTs and LOS (inner core): MSK disease activity, skin disease activity, pain, patient global, physical function, HRQoL, fatigue and systemic inflammation. In addition, the following outcomes (middle circle) are strongly recommended but these may not be feasible in all RCTs and LOS: economic cost, emotional well-being, participation and structural damage. Outcomes that need to be studied further due to their importance for people with PsA include independence, sleep, stiffness and treatment burden. The updated 2016 PsA core domain set is represented in figure 3. All areas of the OMERACT Filter 2.0 framework (pathophysiology, life impact and resource utilisation) have been addressed by this core domain set.

Figure 3.

Updated 2016 psoriatic arthritis (PsA) core domain set. Musculoskeletal (MSK) disease activity includes peripheral joints, enthesitis, dactylitis and spine symptoms; skin activity includes skin and nails; patient global is defined as patient-reported disease-related health status. The inner circle (core) includes domains that should be measured in all PsA randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and longitudinal observational studies (LOS). The middle circle includes domains that are important but may not be feasible to assess in all RCTs and LOS. The outer circle or research agenda includes domains that may be important but need further study.

The 2016 core domain set builds on the first PsA core domain set crafted in 2006.5 Major changes include the movement of fatigue to the inner core and inclusion of participation and emotional well-being as strongly recommended but not mandatory domains for measurement. Additionally, enthesitis and dactylitis are now part of the inner core and are combined with peripheral arthritis as MSK disease activity.

Discussion

In this article, we report the development of the 2016 OMERACT-endorsed PsA core domain set and the steps taken to reach consensus among patients and physicians. The patient perspective was integrated throughout each phase of the research. The qualitative research components and PRP involvement at each step give validity to the resulting proposed domains for PsA clinical trials.14 The sampling process was inclusive of patients from five continents, with a broad spectrum of PsA manifestations, varied levels of disease activity and socio-demographic characteristics, which increases generalisability of our findings.

Our findings confirm the previously demonstrated broad life impact of PsA. Critical elements of life impact for patients with PsA are fatigue, participation and emotional well-being.23 Fatigue was previously recommended for measurement in all PsA RCTs.24 While fatigue has been measured in only approximately one-third of RCTs,12 it has been demonstrated to improve with effective therapy.25–27 Aspects of participation and emotional well-being also have been demonstrated to improve to approximate matched norms with biological therapy for PsA.2 Measurement of participation and emotional well-being needs to be explored for use in PsA RCTs and might in the future, together with fatigue, replace the generic construct of HRQoL. In addition to life impact, the core domain set we propose also emphasises the importance of measuring all facets of the pathophysiology of PsA, including enthesitis, dactylitis, spine and nail disease. These are all disabling elements of the disease but often considered secondary to the peripheral arthritis classically associated with PsA.9 Systemic inflammation is similarly highlighted as it may lead to increased morbidity and mortality through comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes.28 29

Strengths of this study include an international representation of PsA patient participants in focus groups and international representation of patient and physician stakeholders who participated in the surveys and consensus meeting. We followed rigorous research methods, had equal representation of patients and physicians at the consensus meeting and involved PRPs in each step of the process. However, our study also had limitations. Surveys were only in English and French, and therefore, limited selection of patients to those speaking one of these languages in the international web-based surveys. Similarly, the consensus meeting was conducted in English and limited to English-speaking international patients and physicians. On the contrary, the international focus groups were conducted in the native language and translated by linguistically and culturally competent translators with review by native coinvestigators. International focus group participants were sampled across PsA manifestations, disease activity and duration and socioeconomic status. This ensured that we captured broad content early on in the process of data collection and obtained domains that are generalisable to people with PsA worldwide.

This study confirms that patients' and physicians' priorities are different. A core domain set with face validity should capture the diversity of stakeholder perspectives.6 30 We demonstrated that the inclusion of patient and physician perspectives is possible using a data-driven process and ensuring awareness of both perspectives throughout the development of a core outcome set. Next steps are examining outcome measures' psychometric properties for measuring each core set domain and selecting a core set of outcome measures that are adequate and not redundant.

In conclusion, patients and physicians include both disease manifestations and aspects of life impact when identifying the domains of importance in PsA. RCTs and observational studies measuring and reporting these outcomes will better represent the heterogeneity of PsA and the impact of therapy on its varied manifestations. Such data will be the starting point to frame treatment discussions and shared decision-making between patients and physicians and address desired therapy selection on an individual basis.

Acknowledgments

The authors kindly acknowledge Heidi Bertheussen, Jeffrey Chau, Rodrigo Firmino, Jana James and Roland MacDonald for their participation in the face-to-face meeting; all patients and physicians who participated in the surveys and Yihui Jiang for programming the international patient and physician surveys. We thank all collaborators who made possible the international focus group study: Jessica Walsh, Suzanne Grieb, Katherine Clegg Smith, Lilian HD van Tuyl, Karen Schipper, Penelope Palominos, Ricardo Xavier, Tania Gudu, Xiao Hui Xin, SoumyaReddy, Rani Sinnathurai, Lyn March, and Clifton Bingham.

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it published Online First. The acknowledgements section has been updated.

Contributors: All authors participated in the conception, design and analyses of the study. A-MO and AO drafted the manuscript and are guarantors. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: A-MO was supported in part by a Scientist Development Award from the Rheumatology Research Foundation and the Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center Discovery Fund. AO was supported by research grant K23 AR063764 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. This work was supported in part by research grant P30-AR053503 (RDRCC Human Subjects Research Core) from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the Camille J. Morgan Arthritis Research and Education Fund. The international focus group study was supported by research grants from Celgene and Janssen. The nominal group technique meeting was supported by research grants from Abbvie, Celgene and Pfizer. The UK focus group study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (Programme Grants for Applied Research, early detection to improve outcome in patients with undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis, RP-PG-1212-20007). Attendance of working group fellows and patient research partners to the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) conference was supported with workshop funds from Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) and OMERACT.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: A-MO reports grants from Celgene and Janssen (to Johns Hopkins University), during the conduct of the study; consulting fees from Janssen, outside the submitted work. MdW reports grants from Celgene and Janssen (to Johns Hopkins University), during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from BMS, outside the submitted work. PM reports grants and other from AbbVie, grants and other from Amgen, grants and other from Bristol Myers Squibb, grants and other from Celgene, other from Crescendo, other from Corrona, other from Demira, other from Genentech, grants and other from Janssen, grants and other from Lilly, other from Merck, grants and other from Novartis, grants and other from Pfizer, grants and other from Sun, grants and other from UCB, other from Zynerba, during the conduct of the study. WT reports grants, consulting and speaker fees from Abbvie, Pfizer, UCB, Novartis and Celgene. OFG reports grants and/or consulting fees from Abbvie, Pfizer, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Novartis, UCB, Lilly. NG reports she is a full-time employee of Quintiles, Inc. PH reports personal fees from Celgene, outside the submitted work. NMcH reports grants from UK Government to Host Institution, during the conduct of the study. MdW and VS are members of the executive of OMERACT, an organisation that develops outcome measures in rheumatology and receives arms-length funding from 36 companies.

Ethics approval: The focus group studies were approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board (IRB), Baltimore, Maryland, USA (NA_00066663), National Research Ethics Service Committee North West—Haydock, UK (REC reference: 15/NW/0609) and by local ethics committees at each site. The Delphi procedure was approved or considered exempt by the IRBs or ethics boards at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA), Johns Hopkins (Baltimore, Maryland, USA) (IRB00093948), St. Vincent's University Hospital Research and Ethics committee (Dublin, Ireland), SingHealth Centralized IRB (Singapore), and Comité pour la Protection des Personnes Ile de France VI, Hopital Pitié-Salpétriere (Paris, France).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data from this study will be shared upon request. Contact the corresponding author for such inquiries.

References

- 1.Husted JA, Gladman DD, Farewell VT, et al. Health-related quality of life of patients with psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2001;45:151–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strand V, Sharp V, Koenig AS, et al. Comparison of health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis and effects of etanercept treatment. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1143–50. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stamm TA, Nell V, Mathis M, et al. Concepts important to patients with psoriatic arthritis are not adequately covered by standard measures of functioning. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:487–94. 10.1002/art.22605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Wit M, Campbell W, FitzGerald O, et al. Patient participation in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis outcome research: a report from the GRAPPA 2013 Annual Meeting. J Rheumatol 2014;41:1206–11. 10.3899/jrheum.140171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Strand V, et al. Consensus on a core set of domains for psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2007;34:1167–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boers M, Kirwan JR, Wells G, et al. Developing core outcome measurement sets for clinical trials: OMERACT filter 2.0. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:745–53. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Wit MP, Berlo SE, Aanerud GJ, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for the inclusion of patient representatives in scientific projects. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:722–6. 10.1136/ard.2010.135129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gossec L, Smolen JS, Ramiro S, et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2015 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:499–510. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for research and assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2016;68:1060–71. 10.1002/art.39573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalyoncu U, Ogdie A, Campbell W, et al. Systematic literature review of domains assessed in psoriatic arthritis to inform the update of the psoriatic arthritis core domain set. RMD Open 2016;2:e000217 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ritchlin CT, Kavanaugh A, Gladman DD, et al. Treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1387–94. 10.1136/ard.2008.094946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orbai AM, Mease PJ, de Wit M, et al. Report of the GRAPPA-OMERACT Psoriatic Arthritis Working Group from the GRAPPA 2015 Annual Meeting. J Rheumatol 2016;43:965–9. 10.3899/jrheum.160116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palominos PE, Gaujoux-Viala C, Fautrel B, et al. Clinical outcomes in psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:397–406. 10.1002/acr.21552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keeley T, Williamson P, Callery P, et al. The use of qualitative methods to inform Delphi surveys in core outcome set development. Trials 2016;17:230 10.1186/s13063-016-1356-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2665–73. 10.1002/art.21972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santos HP Jr, Black AM, Sandelowski M. Timing of translation in cross-language qualitative research. Qual Health Res 2015;25:134–44. 10.1177/1049732314549603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000;320:114–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van de Ven AH, Delbecq AL. The nominal group as a research instrument for exploratory health studies. Am J Public Health 1972;62:337–42. 10.2105/AJPH.62.3.337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bykerk VP, Lie E, Bartlett SJ, et al. Establishing a core domain set to measure rheumatoid arthritis flares: report of the OMERACT 11 RA flare Workshop. J Rheumatol 2014;41:799–809. 10.3899/jrheum.131252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.OMERACT. Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (cited 15 July 2016). http://www.omeract.org

- 22.WHO. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002:9–10 (cited July 2016). http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/training/icfbeginnersguide.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gossec L, de Wit M, Kiltz U, et al. A patient-derived and patient-reported outcome measure for assessing psoriatic arthritis: elaboration and preliminary validation of the Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease (PsAID) questionnaire, a 13-country EULAR initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1012–19. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tillett W, Eder L, Goel N, et al. Enhanced patient involvement and the need to revise the core set—report from the psoriatic arthritis working group at OMERACT 2014. J Rheumatol 2015;42:2198–203. 10.3899/jrheum.141156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gladman D, Fleischmann R, Coteur G, et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol on multiple facets of psoriatic arthritis as reported by patients: 24-week patient-reported outcome results of a phase III, multicenter study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1085–92. 10.1002/acr.22256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strand V, Mease P, Gossec L, et al. Secukinumab improves patient-reported outcomes in subjects with active psoriatic arthritis: results from a randomised phase III trial (FUTURE 1). Ann Rheum Dis 2016; Published Online First 11 May 2016. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-209055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strand V, Schett G, Hu C, et al. Patient-reported Health-related Quality of Life with apremilast for psoriatic arthritis: a phase II, randomized, controlled study. J Rheumatol 2013;40:1158–65. 10.3899/jrheum.121200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogdie A, Yu Y, Haynes K, et al. Risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:326–32. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dubreuil M, Rho YH, Man A, et al. Diabetes incidence in psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a UK population-based cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:346–52. 10.1093/rheumatology/ket343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirkham JJ, Gorst S, Altman DG, et al. COS-STAR: a reporting guideline for studies developing core outcome sets (protocol). Trials 2015;16:373 10.1186/s13063-015-0913-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Domain discussion and assignment to core, outer circle, research agenda, contextual factors or adverse events during the nominal group technique consensus meeting with patients and physicians

annrheumdis-2016-210242supp001.pdf (116.1KB, pdf)

Proposed updated psoriatic arthritis core domain set at the conclusion of the nominal group technique meeting with patients and physicians: MSK (musculoskeletal) disease activity includes peripheral joints, enthesitis, dactylitis and spondylitis; skin activity includes skin and nails; patient global is defined as patient reported disease related health status; participation (e.g. family roles, social, leisure, work/employment); emotional well-being (e.g. depressive mood, anxiety, embarrassment, selfworth, frustration, stress); structural damage* should be measured at least once during a drug development program for PsA;

annrheumdis-2016-210242supp002.pdf (129.9KB, pdf)