Abstract

Previous research on associative learning has uncovered detailed aspects of the process, including what types of things are learned, how they are learned, and where in the brain such learning occurs. However, perceptual processes, such as stimulus recognition and identification, take time to unfold. Previous studies of learning have not addressed when, during the course of these dynamic recognition processes, learned representations are formed and updated. If learned representations are formed and updated while recognition is ongoing, the result of learning may incorporate spurious, partial information. For example, during word recognition, words take time to be identified, and competing words are often active in parallel. If learning proceeds before this competition resolves, representations may be influenced by the preliminary activations present at the time of learning. In three experiments using word learning as a model domain, we provide evidence that learning reflects the ongoing dynamics of auditory and visual processing during a learning event. These results show that learning can occur before stimulus recognition processes are complete; learning does not wait for ongoing perceptual processing to complete.

Keywords: Word learning, associative learning, processing dynamics, temporal processes, lexical access

A century of research on learning offers detailed mechanistic understanding of how learners come to link various representations (what we broadly refer to as associative learning). This work has elucidated what sorts of things can be learned. Major branches of cognitive science study what types of associations form most easily and what constraints control the things that are learnable (e.g., Goldstone & Landy, 2010; Munakata & O’Reilly, 2003; Thiessen, 2011). Research has also uncovered much about where in the brain associative linkages occur. We have complex understanding of how different neural circuits accommodate different types of information, and how this information is stored within neural circuits (J. H. Freeman, 2010; O’Reilly & Norman, 2002). Further, we know how associations are built; that is we have clear theories and models of how information is combined to strengthen and weaken associations (Hebb, 1949; Rescorla & Wagner, 1972; Rumelhart, Hinton, & Williams, 1986) and of the complex emergent products that arise when many such associations are built simultaneously (O’Reilly & Munakata, 2000; Seidenberg & McClelland, 1989; Wasserman, Brooks, & McMurray, 2015).

However, we do not yet know when learning occurs. It is clear that learning does not link raw perceptual inputs (if there is such a thing) to each other; rather stimuli are processed, encoded, represented, and/or categorized either during learning or prior to it. Such processes unfold dynamically over time (Spivey, 2007). What is not clear then is when—during these dynamically unfolding processes—associative linkages are formed. Are learning systems intelligent enough to wait until this processing is complete before forming associations? Or is learning much simpler and “always on,” forming associations while dynamic processing is ongoing?

Much prior work on associative learning has employed unambiguous stimuli such as lights and tones or basic visual stimuli like Gabor patches. For these stimuli, processing is extremely rapid, and processing dynamics are relatively simple. As a result, theories of learning based on these results did not need to address the dynamics of stimulus processing – such theories can assume immediate stimulus identification without compromising their fit to the data, or they can assume that any processing dynamics simply add noise to the system.

However, more complex stimuli require more protracted, complex processing, especially when these stimuli are themselves temporally extended. When perceiving sequential stimuli like musical sequences or words, learners take in information across time, with multiple representations competing for recognition as the input is received (Bharucha, 1987; McClelland & Elman, 1986). Even for simple perceptual decisions, single-unit recording studies with non-human primates show ongoing competition between multiple representations at the neuronal level (Shadlen & Kiani, 2013), and human studies using techniques like mouse-tracking and ERPs show similar unfolding dynamic competition (Huette & McMurray, 2010; McKinstry, Dale, & Spivey, 2008; Miller & Hackley, 1992). From the earliest moments of stimulus processing, the decision making system considers multiple candidate interpretations of the input in parallel.

This temporally extended processing creates a challenge for theories of associative learning: a unitary or discrete interpretation of a stimulus (e.g., a single choice out of multiple competing choices) may only be possible late in processing (if at all). How does the learning system know when processing is done so that representations can be linked? If learning occurs before these recognition processes are complete, the learner might form multiple partial associations with partially activated representations. Whether learning occurs before processing is complete or whether it waits could ultimately have a large impact on what learners end up linking, because different representations may be active at different times.

Spoken words offer a clear example of this problem. At early moments of lexical processing, multiple words can match the input. For example, after hearing the acoustic sequence “ba-”, the input is consistent with bag, battle, ballast, and so on. Listeners do not wait until ambiguity resolves to begin activating words. Instead, multiple words are activated in parallel, and identification proceeds through competition between these multiple candidate words as more input is received (Allopenna, Magnuson, & Tanenhaus, 1998; Gaskell & Marslen-Wilson, 2002; Marslen-Wilson & Zwitserlood, 1989; Marslen-Wilson, 1987; McMurray, Clayards, Tanenhaus, & Aslin, 2008; McQueen, Norris, & Cutler, 1994). This competition can be altered by fine-grained detail in the bottom-up acoustic signal (Andruski, Blumstein, & Burton, 1994; Dahan, Magnuson, Tanenhaus, & Hogan, 2001; Marslen-Wilson & Warren, 1994; Salverda et al., 2006), expectations set up by preceding knowledge (Salverda, Kleinschmidt, & Tanenhaus, 2014), knowledge of the phonotactics of the language (Magnuson, Dixon, Tanenhaus, & Aslin, 2007), top-down information about likely words in a given context (Connine, Blasko, & Hall, 1991; Dahan & Tanenhaus, 2004), and active inhibition among competing words (Dahan et al., 2001; Luce & Pisoni, 1998). Word recognition thus exhibits complex dynamics as multiple information sources affect the dynamics of the competition process.

This miasma of active lexical candidates raises problems for learning how to map new words onto their referents. If we assume similar dynamics of processing for new word-forms that are being learned, at what point in this processing can these word-forms be linked to referents? Does the learner only form/update the linkages between word-forms and referents after all competition is resolved, even if the learning event encourages earlier learning? How does associative learning cope with multiple activated representations whose activations fluctuate across time? Learners appear to have a moving target of association, as the correct word-form is rarely active in isolation. If learning occurs while competing word forms are co-active, this could result in spurious mappings as the phonological competitors are linked to the incorrect meaning. Delayed learning occurring after competition resolves would avoid such spurious mappings. Because the items that are active change over time, when learning occurs might shape what is actually learned.

For example, while a learner is acquiring words like gonu and goba (as in the studies below), at the onset of the word, when only “go-” has been heard, she will briefly activate both of these word-forms before the disambiguating information late in the word arrives, conforming to the normal principles of spoken word recognition elucidated for familiar words. However, if a referent is available at this time (e.g. a gonu is displayed), and if learning occurs before this competition resolves2, she may link this referent to both of the activated word-forms. Practically, only after the whole word has been heard can she determine that the object should be correctly mapped to the word form gonu and not goba but if learning does not wait for this, it may be problematic. Learning before competition resolves would lead to a correct association between the gonu and the lexical item “gonu,” but also a spurious association between the gonu and the competitor (“goba”).

Certain word learning paradigms or situations may allow learning to unfold during competition, which might encourage such spurious associations. For example, word learning is often thought to invoke unsupervised or observational learning (Akhtar, Jipson, & Callanan, 2001; McMurray, Horst, & Samuelson, 2012; Medina, Snedeker, Trueswell, & Gleitman, 2011; Ramscar, Dye, & Klein, 2013; Siskind, 1996; Yu & Smith, 2007). In such unsupervised learning schemes, learning could occur at any time after the stimuli are presented. In the simplest forms of unsupervised learning (e.g., McMurray et al., 2012; Yu & Smith, 2012), associations form between any co-active representations, without regard for the state of competition within the system. Such systems predict that word-object links would form during periods of competition, when multiple word-forms are partially active, leading to multiple erroneous linkages between competing lexical items and a referent. For example, when acquiring phonologically similar novel words like gonu and goba (as in the experiments reported below), the learner will partially activate both word-forms after hearing go-. If learning occurs before this parallel activation resolves, each word-form will become associated with whatever referents are present.

More intelligent forms of unsupervised learning may incorporate mechanisms to attenuate or eliminate this effect. For example, learners might rely on hypothesis generation and testing. This type of learning suggests that learners form only a single hypothesized referent for a given word-form; however, after encountering evidence that this mapping is wrong (e.g., the hypothesized referent is not present when a word is heard), the learner completely overwrites the previous association. Under these schemes, the emphasis on a single hypothesis would suggest that it is likely that the lexical competition would need to resolve prior to the generation and/or evaluation of hypotheses. Consequently, learning would likely only occur when a single word-form and a single referent are selected (Medina et al., 2011; Trueswell, Medina, Hafri, & Gleitman, 2013). The strong form of this hypothesis-generation form of word learning thus predicts that parallel activation of multiple word-forms during word recognition is tangential to the word-referent learning that occurs, and that learning would likely wait for lexical competition to complete before learning can begin.

Some models using more associative forms of unsupervised learning also incorporate mechanisms that could halt learning until competition resolves, eliminating the threat of spurious associations during ongoing competition resolution. For example, activation thresholds (Samuelson, Smith, Perry, & Spencer, 2011; Schutte, Spencer, & Schöner, 2003) or competition monitors (Griffiths, Steyvers, & Tenenbaum, 2007) could be used to track the state of real-time processing to determine whether activation is stable enough for learning to proceed. These mechanisms would delay learning while multiple items compete for activation, thereby avoiding spurious linkages; learning in these architectures is only on the basis of post-competition stimulus representations. A learner utilizing such competition monitors would only learn on the basis of the items that win the competition, as learning is blocked earlier. However, there is as yet no empirical basis that would support or refute these forms of competition monitoring.

It is unknown whether word learning (or other forms of learning) contains such gating mechanisms to block learning during parallel activation, or if instead learning can occur earlier during stimulus recognition processes. The learning process might be a smart or gated system that prevents parallel associations from forming while processing dynamics are under way. Alternatively, it might operate in real-time, with associations beginning to form as soon as potential targets of association are available. Under this view, which we term “dynamic learning” in reference to the real-time dynamics of processing, learning can occur as soon as associative targets are available even if multiple targets are coactive, and it may link many briefly considered stimuli.

The current studies assess these possibilities by investigating how associative learning between words and objects interacts with unfolding activation dynamics of word recognition. Word learning offers an ideal domain to investigate the interactions between stimulus processing and learning, as the dynamics of lexical activation are complex, but also well studied. The answer to how learning operates in the lexical domain has important implications for learning more generally; if processing dynamics and learning interact directly in word learning, it suggests a general tendency for the associative learning system to rely on very simple learning that occurs throughout processing even for complex stimuli.

We ask when during processing the links between words and referents are formed: can learning occur while multiple stimuli are active, or is it confined to operate only after competition resolves when one-to-one mappings are more readily available? We addressed this with an adaptation of a common unsupervised word-learning paradigm (cross-situational learning) that allows control over when learners have the opportunity to form associations during a trial. Participants learned partially overlapping words (goba/gonu) to provide a learning situation in which learners can co-activate competing word-forms during word recognition. We then manipulated the onset of the visual referents to either occur simultaneously with the word-form (providing the opportunity for both active word-forms to be linked to the referents during stimulus recognition) or after competition has completed (so that only the representation that emerged after competition resolved can be linked to the referents). After learning, we used a common variant of the visual world paradigm (Tanenhaus, Spivey-Knowlton, Eberhard, & Sedivy, 1995) to determine whether lexical competition was increased by simultaneous presentation, which would indicate spurious learned associations with competing word-forms. Specifically, if spurious associations were formed during learning, participants should show greater consideration of competitor items (as indicated by more fixations to competitors), even when correctly recognizing a target word. If a learner has formed a spurious association between the referent of goba and the word-form “gonu,” then they should show increased looks to the goba object when hearing “gonu.”

Prior work using a similar paradigm (Roembke & McMurray, 2016) has established that this combination of eye-tracking and cross-situational learning can detect partial spurious associations between words and objects (although this study did not investigate the dynamics of lexical competition). In this study, even as participants were clicking on the correct referent of a newly learned word, they simultaneously showed increased fixations to other plausible associates. This suggests that learners maintain multiple potential referents for a given word (see also, Dautriche & Chemla, 2014), and that both can influence behavior within a single trial as they are simultaneously clicking on one referent and showing increased fixations to another. Here we employ a similar logic to show that spurious associations between phonological competitors are indeed partially formed additional associations. If a learner is selecting the correct referent but simultaneously showing increased fixations to a phonological competitor, it would suggest that the learner has laid down two associations. That is, this logic establishes the parallelism of the learning: two word-forms that are momentarily active in parallel during learning lead to two associations that simultaneously shape behavior in parallel at test.

Across experiments, we show evidence that learners form associations when multiple word-forms are active and competing if referents are available. Further, we show that this learning interacts with a number of different aspects of ongoing processing dynamics.

Experiment 1: Manipulating the timing of associative learning

Experiment 1 tested our primary hypothesis that learning could occur for multiple competing word-forms before lexical competition resolves. We manipulated when the visual referents were presented in a word learning task to alter when the learning system could begin forming associations. In the simultaneous condition, visual referents were presented simultaneously with the auditory words. If learning is always on, this should allow associative links to be potentially laid down immediately while competition is ongoing and multiple word forms are partially active. This learning in the simultaneous condition was compared with a delayed condition in which visual referents were presented several hundred milliseconds after the auditory words, after competition has presumably resolved on a single word-form interpretation. In this condition no associations could be formed during periods of competition, as no referents were present. This should block the spurious associations formed in the synchronous condition. Both conditions present the same information, and the duration of both auditory and visual presentation is the same for both; only the relative onset of the auditory and visual information differs between conditions.

After learning we assessed whether spurious associations with competing word-forms had developed using a variant of the visual world paradigm (VWP) to assess how strongly different items were considered (fixated) in the presence of a newly learned word. A learning system that delays learning until after competition resolves predicts no difference in the types of associations that are formed as a function of when referents are presented relative to auditory stimuli; whether competition has resolved on its own before the referent appears or the learning system waits, no associations are formed until a one-to-one mapping is available. Consequently at test, learners in both conditions should occasionally fixate the competitor (since a target like gonu is temporarily ambiguous with its competitor, goba). However these fixations should not differ between conditions as they are completely driven by the bottom up input, not by associations formed during learning.

In contrast, a dynamic learning system predicts that in the simultaneous condition learners may form parallel associations between multiple partially active word-forms and the visual referent. However, in the delayed condition, they should only form one-to-one mappings. Thus, this predicts that simultaneous presentation during training should lead to increased fixations to the competitor at test – driven by both the bottom up input and the spurious associations. We tested whether these associations had formed by comparing competitor effects after learning; spurious associations with competitors should increase the amount that competitors are considered during word recognition. Testing in this version of the VWP allows measurement of partial associations with multiple items (see also Roembke & McMurray, 2016): if learners simultaneously click the correct referent, and while showing increased fixations to the competing referent, it would suggest that the result of simultaneous training is to establish (at least) two associations.

Methods

Participants

Participants were volunteers from the University of Iowa community who received course credit or monetary compensation for their participation. All participants were monolingual native speakers of English, and they reported no vision, hearing or neurological disorders. Data from 60 participants were included in the analysis: 30 from the synchronous group and 30 from the delay group. Data from an additional 21 participants were not included in analysis because these participants failed to learn the correct word-referent mappings during training (these participants performed worse than 75% correct during the VWP trials for either onset or offset competitor trials). The accuracy data were quite bimodal; included participants averaged over 98% accuracy, whereas excluded participants averaged 50.0%. Eight of the excluded participants were in the delay group, while the remaining 13 were in the synchronous group (χ2(1)=0.85, p=.34). Due to a computer error, two participants in the delay group received fewer than the full 320 VWP trials.

This fairly conservative exclusion criterion was necessary to interpret the eye-tracking data. Because our analysis of competitor effects is predicated on consideration of competitors when a word is recognized, we need to be certain that the correct word is being activated. For participants with low accuracy, even correct trials may be unreliable; if a participant is performing near chance, correct responses may arise because of guessing, so looking dynamics would be unrelated to accurate lexical recognition. Critically, by conditioning the analysis of fixations on an accurate mouse click decision, we can establish whether learners are actively considering two potential referents at test (the one that they clicked on, and the one they are showing enhanced fixations to).

Materials

Auditory stimuli were two-syllable consonant-vowel-consonant-vowel non-words that adhered to the phonotactic rules of English, but did not have meanings. These words included two pairs of onset competitors sharing the first CV (busa/bure; goba/gonu), as well as two pairs of offset competitors sharing the second CV (jafa/mefa; pacho/lucho). Auditory stimuli were recorded from a male native speaker of English in a sound-treated room. Stimuli were adjusted to have consistent peak amplitudes, and 100 ms of silence was added to the beginning and end of each. Twenty-six exemplars of each word were used. For each participant, a random set of 16 exemplars of each stimulus was selected for the training trials; the remaining 10 exemplars were used in testing. This meant that participants only heard each exemplar a few times over the course of the experiment, preventing them from anticipating which word they were hearing on the basis of surface variability between productions.

Visual stimuli were color photographs of eight hard-to-identify objects (Figure 1), excised from background context. The word-object pairings were randomized for each participant.

Figure 1.

Examples of visual stimuli used in the experiments (images in the experiment were in color).

Procedure

Participants learned associations between the eight novel words and visual referents. The experiment included three phases: a word-form learning phase, a cross-situational word-referent mapping phase and a VWP testing phase. Before beginning the experiment, a head-mounted Eyelink II eye-tracking was placed on the participants head, and a standard nine-point calibration procedure was conducted.

Experiments began with a phoneme monitoring task to familiarize participants with the word-forms used in the study before the word-referent learning (Gaskell & Dumay, 2003; Kapnoula, Gupta, Packard, & McMurray, 2015). This was done to make it more likely that even by the beginning of the word-referent associative learning trials, competitor word-forms would be learned well enough to be coactive; from the first trials, when hearing go-, learners knew that both gonu and goba were potential completions of the item. Participants received exposure to the auditory form of the words without any accompanying meaning, and they were told that the words from this pre-exposure would be used in subsequent learning tasks. Participants heard one of the words from the study, and they were instructed to press the space bar if the word contained an “O” sound, and to do nothing if it did not. Half of the novel words used in the study had “O” sounds, and half did not. Participants completed 64 trials, hearing each word eight times in a random order. Participants had 2000 ms to register a response before the next trial began.

Next participants completed the word-referent associative learning trials. Words were trained using a passive, cross-situational learning paradigm (Yu & Smith, 2007), which allowed us to manipulate when (during lexical processing) the referents were available for association. This paradigm typically requires multiple exposures to each word in order for words to be fully learned. This provides increased opportunity for spurious associations with competitors to strengthen. On each trial, participants saw two candidate referents and heard a word. One visual stimulus was the referent of this word; the other was drawn randomly from the other stimuli, except that it was never the referent of the target’s phonological competitor; that is, if the auditory stimulus for a trial was “gonu,” a gonu was on the display, but the foil item was never a goba. This ensured that no bottom-up co-occurrence statistics supported mappings between a referent and the phonological competitor (they never co-occurred).

Participants initiated each trial by clicking a central point. After this, the specific events on a given trial were controlled by the timing condition, as described below. We used a variant of the classic cross-situational learning in which participants made no overt response on any of the learning trials (unlike, for example, recent studies by Trueswell et al., 2013; and Roembke & McMurray, 2016). Participants were told that each trial, one of the displayed images matched the spoken word, and that they should try to learn the correct pairings. Training included 32 blocks of eight trials (each word with its correct referent once). The location of the correct referent and the identity of the foil were randomly assigned for each trial. The timing of visual and auditory presentation varied between conditions, providing different times when participants could form associations.

For participants in the synchronous group, visual and auditory stimuli were presented simultaneously 100 ms after the start of the trial. The visual stimuli then remained on the screen for 800 ms. In the delay condition, the auditory stimulus began 100 ms after the dot was clicked, but the screen remained blank for another 1000 ms, at which point the visual stimuli were displayed. Because the longest auditory stimulus was 740 ms (including 100 ms of silence at the onset of the file), the visual stimuli always appeared well after word offset in the delay condition. As in the synchronous group, the visual stimuli then remained on the screen for 800 ms. In both groups there was an inter-trial interval of 550 ms.

After every fourth block of training trials, participants in all conditions completed four interim testing trials in which a single visual stimulus was presented along with an auditory word. Participants were told to indicate whether this word was the correct label for the visual stimulus. These trials were included to ensure that participants maintained attention throughout the experiment and to provide a coarse measure of learning during training. Each word was played four times for interim testing throughout the experiment: twice with the correct referent, and twice with a randomly-selected mismatching referent (never the referent of the phonological competitor). Participants were alerted before these trials to ensure that they were prepared to make responses. For these trials, the visual and auditory stimuli were presented simultaneously for all participants. Note that these trials provided participants in the delay group with a small number of synchronous trials; this could weaken differences between groups, meaning that any effects found might underestimate effect sizes that would occur with fully differentiated training. Participants clicked on “match” and “mismatch” buttons on the display to indicate whether they believed an accurate pairing was given.

After learning, participants performed a four-alternative VWP task (Tanenhaus et al., 1995) to gauge which associations (both correct and spurious) were learned. Participants were presented with four visual stimuli and a central fixation dot. Each trial contained two pairs of phonological competitors: one onset competitor pair and one offset competitor pair; pairings were randomly chosen for each participant and were consistent throughout the test trials. They clicked a dot to initiate the trial, at which point the dot disappeared. A word was played 100 ms later, and the participants clicked the referent of the word to signal what object they believed the word referred to.

The timing of the VWP test trials was identical for participants in both synchronous and delay conditions. Fixations were tracked throughout these trials to determine the degree that the target, its competitor and the two unrelated foils were considered during the trial. The dynamics of familiar word recognition predict that participants should fixate both targets and competitors (Allopenna et al., 1998). However, if word/object learning occurred before competition resolved, spurious associations with competing word-forms formed during periods of competition should elicit even greater competitor fixations, as these fixations would reflect both phonological overlap and associative linkages between the referent and the competitor word. On the other hand, if word/object learning waits for competition to resolve, then fixations should be driven by phonological overlap alone, and we should observe similar performance for participants in the synchronous and delay timing conditions of the word-referent associative learning trials; for both conditions, learning only occurs after competition settles on a single interpretation. Item location was randomized for each trial. Participants completed 40 blocks of trials, with each word presented once per block (320 total trials).

Analysis

Data were analyzed with mixed effects models (Baayen, Davidson, & Bates, 2008; Jaeger, 2008) using the lme4 package (version 1.1–6) in R (Bates & Sarkar, 2011). We used the lmerTest function (version 2.0–6) to compute p-values. Analysis of accuracy data used a binomial linking function, and data were entered as binary values signaling accuracy on each trial.

Eye-movement data were analyzed with linear models. For analyses of target looks, the DV was the proportion of looks to the target from 500 to 1500 ms after auditory stimulus onset, transformed with the empirical logit function ( ). This onset time was selected because it coincided with the beginning of consistent competitor fixations; the stimuli contained 100 ms of silence at onset, and it takes 200 ms to program an eye-movement so this onset signals looks generated after approximately 200 ms of stimulus had been heard. The offset of the window (1500 ms) coincided with where looks to competitors and unrelated objects significantly declined. Use of other time windows showed very similar results.

For analysis of competitor fixations (our primary measure) we used a different transformation (see also Roembke & McMurray, 2016). The empirical logit (as we used for target fixations) only takes into account fixations to one object (in this case, the target). However, for looks to the competitor, it was important to evaluate the degree to which competitor looks exceeded fixations to unrelated objects to account for possible overall changes in looking behaviors. These unrelated looks are not independent of competitor looks (because if the participant is looking at the competitor she can’t look at the unrelated object). Thus, we derived a closely related scaling, by computing log-odds ratios of competitor to unrelated looks ( ). This shows the degree to which the competitor looks exceed the looks to the unrelated. Because there were two unrelated items in the display and only one competitor, we used the average looks to both unrelated items. Note that this analysis does not consider the number of looks to the target items in the display, as we were interested in how competitor fixations compared to fixations to items completely unrelated to the auditory stimulus.

This log-odds ratio was used as the DV for analyses of competitor effects. Log-odds ratios greater than 0 signify greater consideration of the competitor than the unrelated objects. Because this measure treats competitor looks relative to unrelated looks, it estimates competition with respect to the overall tendency to fixate any item on the display. This ensures that effects from learning are not artifacts of more general changes in the willingness to fixate any visual stimuli. Because non-zero values are needed in both the numerator and denominator of the odds ratio to calculate a meaningful log-odds ratio, we computed these log-odds ratios using the mean of competitor and unrelated looks across all repetitions of each stimulus for each participant for this analysis (individual trials have a much higher likelihood of a participant not looking at one of the item types).

DVs for the eye-movement data were computed for each stimulus for each subject and used in a linear mixed effects model. P-values for individual coefficients were estimated either with the Wald Z statistic (for binomial models) or using the T-statistic using the Satterwaithe approximation for the d.f. (SAS Institute Inc., 1978), which was implemented in the lmerTest package of R. In every model, the fixed factors were timing condition during training (synchronous: −.5; delay: +.5) and word type (onset competitor: −.5; offset competitor: +.5). Participant and auditory word were included as random intercepts. This model structure was chosen based on a comparison of models of varying complexity for the primary analysis (the analysis of log-odds ratios of the competitor effect). These models started with random intercepts of both participant and item, and added slopes for participant on word-type (timing condition was between subject and so could not be a random slope), and for item on timing-condition (items varied between word types, so could not be a random slope). More complex models did not offer a better fit to the data by χ2 test (all p>.6) – this pattern held throughout all experiments.

Results

Learning

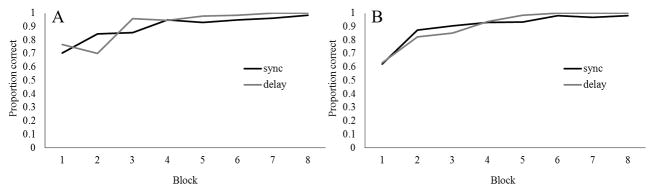

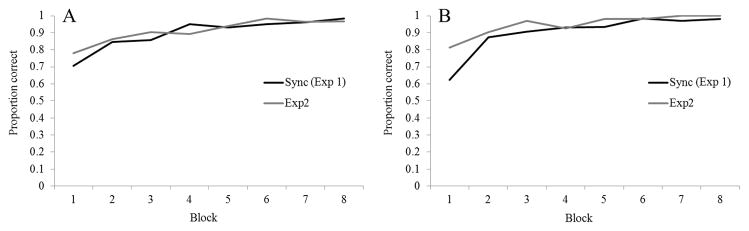

The primary analysis of interest was whether competition during the VWP trials increased in synchronous participants relative to delay participants. However, to ensure that such effects result from spurious associations rather than from overall poorer learning, we needed to establish that the two groups learned effectively. We first considered the accuracy in the interim trials throughout training to determine whether there were differences in the speed or effectiveness with which participants learned the words (Figure 2) which shows that participants reached a high level of accuracy early in training and maintained it.

Figure 2.

Proportion of correct responses during interim testing trials for Experiment 1. A) Onset competitor trials. B) Offset competitor trials.

Statistical analyses are presented in Table 1. For our analysis of the interim trials, fixed effects in the model included block (coded as raw block number), condition (synchronous/delay), and word-type (onset-/offset-competitor) as fixed factors in the model. These analyses showed a significant main effect of block (p<.00001), as performance improved throughout the training blocks. There was also a significant interaction of block and timing condition (p=.013); this interaction reflected an earlier advantage for synchronous participants in the first few blocks and a slight advantage for delay participants at later blocks. No other main effects or interactions approached significance (all p>.16). During the final block of test, both groups reached high levels of performance (Msynchronous=.98; Mdelay=1.0), suggesting that both groups learned the words to ceiling before testing began. Because of the consistently high accuracy and low variance across participants, attempts to model performance on this block produced erratic results.

Table 1.

Results from analyses of accuracy during interim and VWP trials. Significant effects are in bold.

| Model | Comparison | B | SE | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy during interim trials for Experiment 1 | Block | .72 | .062 | 11.63 | <.0001 |

| Timing condition | −.64 | .46 | −1.40 | .16 | |

| Word type | −.37 | .35 | −1.05 | >.2 | |

| Block × timing | .30 | .12 | 2.48 | .013 | |

| Block × type | .094 | .12 | .78 | >.2 | |

| Timing × type | −.054 | .70 | −.076 | >.2 | |

| Block × timing × type | −.022 | .24 | −.091 | >.2 | |

| Accuracy during VWP trials for Experiment 1 | Timing condition | −.27 | .32 | −.85 | >.2 |

| Word type | .38 | .15 | 2.46 | .014 | |

| Timing × type | −.41 | .23 | −1.75 | .080 |

To further examine whether learning differed between groups, we analyzed the accuracy of identifying the correct target during the VWP trials (Table 1). Participants were overall quite accurate (recall that inaccurate participants – those with less than 75% correct on either word type – were excluded from analysis); the remaining participants in both groups were quite close to ceiling (Msynchronous=.99; Mdelay=.98). The groups did not differ (p=.39). However, there was a significant effect of word-type (p=.014), as the onset competitors (M=.98) were slightly less accurately identified than the offset competitors (M=.99). This accuracy difference may arise because of overall greater competition between words that overlap at onset than those that overlap at offset (Allopenna et al., 1998; Marslen-Wilson & Zwitserlood, 1989). There was no interaction of timing condition with word type (p=.080). This confirmed that the two groups did not differ in how well they learned the words.

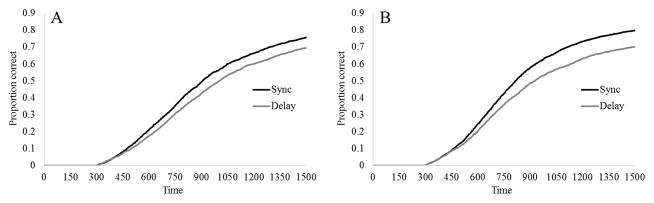

Finally, we analyzed looks to the target items on the VWP task to determine whether participants showed slower or faster latencies to locate the target across the two timing conditions (an indicator of efficiency gains that may result from learning). Difficulty identifying the target could be indicative of poorer learning despite accurate responding. Figure 3 displays the average looks to the target across time during the trial. For analysis, the empirical logit of these looks was taken for the average number of looks between 500 and 1500 ms transformed with the empirical logit function. There was a marginally-significant effect of timing condition (B=−.14, SE=.076, t(58.0)=−1.88, p=.066), as the synchronous group showed greater fixations to the target, counter to predictions of poorer learning by the synchronous group. There was also a main effect of word type (B=.093, SE=.018, t(6.0)=5.02, p=.0024), with greater target looks for words with offset competitors than for words with onset competitors. There was no interaction (B=−.048, SE=.029, t(411.7)=−1.62, p=.11). Across analyses of accuracy and looking time, there was no evidence that participants with synchronous timing struggled to effectively learn the words. This ensures that analysis of competitor effects can proceed without concerns that enhanced competition would arise from poor acquisition of target-referent pairings. This analysis does raise the possibility, however, that the synchronous group may have ultimately learned somewhat better than the delay group (although this conflicts with the slightly higher accuracy in the delay group). We address this concern in greater detail after the results of Experiment 3 and in the Online Supplement, showing that these small differences in learning are unrelated to the magnitude of competitor effects.

Figure 3.

Raw proportion of looks to the target items in Experiment 1. A) Onset competitor trials. B) Offset competitor trials.

Competition

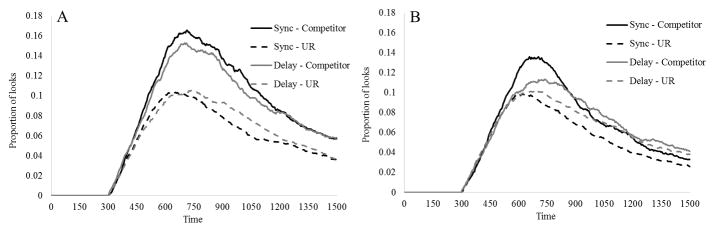

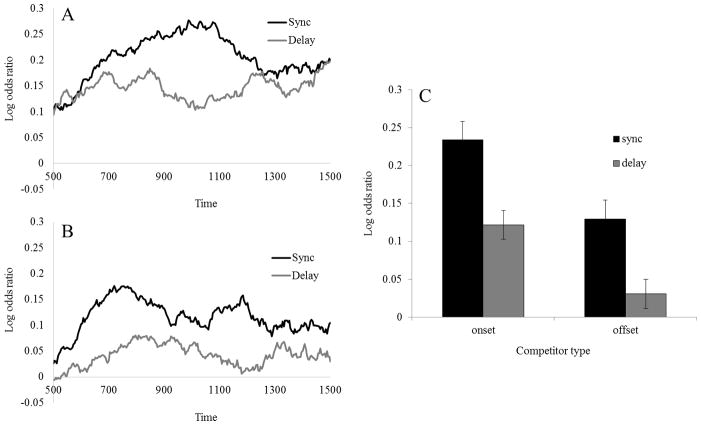

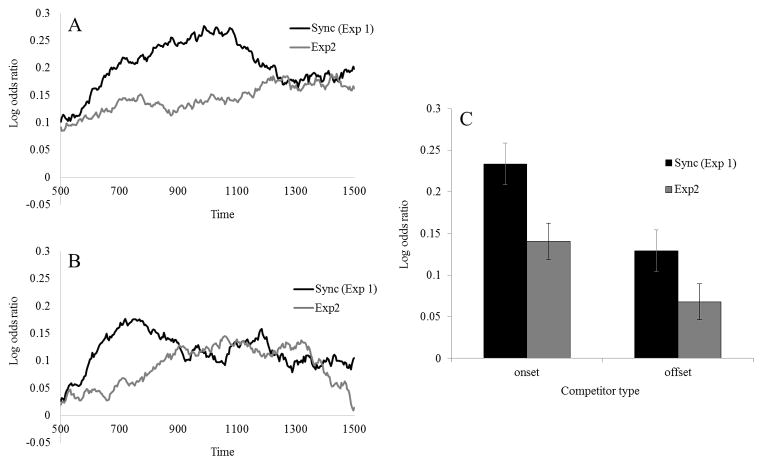

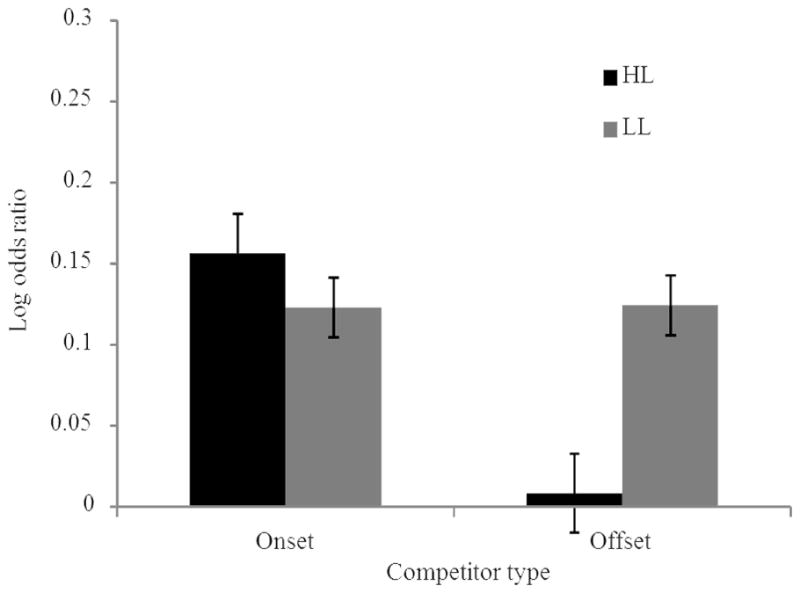

Our primary analysis concerned the effect of timing condition during learning on competition during the VWP testing phase. Figure 4 shows the looks to the competitor and unrelated items as a function of training condition over time. It suggests that changes occurred in both competitor and unrelated looking and justifying our relative measure, the log-odds ratio of competitor looks relative to looks to unrelated objects. In a very few cases (5 out of 480; 4 from delay participants, 1 from synchronous participants), no looks occurred to either the competitor (3 cases) or to the unrelated objects (2 cases) during the time window; these cases resulted in log-odds ratios of negative or positive infinity. These cases were excluded from the analysis3. Recall that in this analysis, log-odds ratios greater than 0 signify greater consideration of the competitor than the unrelated objects. Figure 5A and B present these log-odds ratios over time; Figure 5C shows the average log-odds ratio across the time window for each condition.

Figure 4.

Raw proportion of looks to competitor and unrelated (UR) items in Experiment 1. Unrelated items reflect the mean of looks to the two unrelated items in the display. A) Onset-competitor trials. B) Offset-competitor trials.

Fig. 5.

Competitor effects in Experiment 1. Looks to the competitor are compared to the mean of looks to the two unrelated items. A) Log odds ratio of looks for onset competitors across time. B) Log odds ratio of looks to the offset competitors divided by looks to the unrelated objects across time. C) Mean log odds ratio during analysis window (500–1500 ms) by competitor type and timing condition. Error bars are the standard error of the mean.

This analysis (Table 2) revealed that participants were more likely to fixate the competitor than the unrelated items (as indicated by the intercept; p=.00016). Critically, this effect was magnified for participants in the synchronous condition relative to the delay group (p=.0075); participants who learned the words with visual referents presented during auditory processing of the words looked to the competitor more than those who saw the visual referents after auditory word offset.

Table 2.

Results from analyses of competitor effect during VWP trials. Significant effects are in bold.

| Comparison | B | SE | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | .13 | .024 | 12.1 | 5.40 | .00016 |

| Timing condition | −.10 | .038 | 57.0 | −2.77 | .0075 |

| Word type | −.096 | .039 | 6.0 | −2.43 | .051 |

| Timing × type | .016 | .052 | 406.1 | .30 | >.2 |

The effect of word type approached significance (p=.051); as would be expected given previous research, there were greater competitor effects for onset competitors than for offset competitors. The interaction was not significant (p=.76), signaling that the increased competitor effect for the synchronous group was consistent for the two types of competitors.

Discussion

The increased competitor fixations in the synchronous group suggest that learning can occur before competition resolves, resulting in spurious associations with co-active word forms. This occurred despite the referent of a target word never co-occurring with that of its competitor; there is no basis in physical co-occurrence for these spurious associations. Instead, it appears that these associations arise because competitor words are activated during real-time lexical processing during training. When stimulus timing allows learning to occur before this competition resolves, the competing word-forms are both linked to the presented referents. Experiment 1 thus supports the dynamic-learning hypothesis that associative learning can proceed before competition is complete. Rather than waiting until competition resolves, associative links are formed while multiple representations are active, leading to multiple parallel associations.

The lack of interaction between timing condition and word type is somewhat surprising. Although the expected decrease in competition from offset competitors (Allopenna et al., 1998) was seen (across both timing conditions), the increase in competitor effects for the synchronous group was equivalent for onset and offset competitors. One might predict that offset competitors should elicit fewer spurious competitors; during recognition, the decreased activation of these competitors should limit the strength of spurious associations that can form. Evidence from previous studies of novel word learning, however, suggests that offset competitors may show greater activation early in learning (Magnuson, Tanenhaus, Aslin, & Dahan, 2003), when we predict spurious associations are most likely to form. Magnuson and colleagues found that when learning novel words, rhyme competitors showed quite large competition early in learning, with very early effects showing nearly equivalent competition to cohort competitors. Because spurious associations are predicted to form through coactivation early in learning, such large offset competitor effects may arise because of these early strong rhyme activations.

As a whole these results appear to support a dynamic learning hypothesis. However, an alternative explanation is that these effects were simply driven by differences in how well the items were learned which could affect the degree of competition. It is unclear if this is a viable explanation. On the interim testing trials, participants in the delay condition were slightly more accurate by the end of testing, though this difference did not appear on the accuracy in the VWP trials. However, target fixations (a measure of efficiency) rose marginally faster in the synchronous condition, providing evidence that the delay group may have learned more poorly. Thus, evidence is mixed concerning a different in overall learning. We address whether differences in how well the words were learned could elicit the competitor effects seen here shortly after Experiment 3, as well as with extensive analyses reported in the Online Supplement. In short, these supplementary analyses provided no evidence that differences in the strength of learning impacted the degree of competitor effects.

Experiment 2: Updated learning during ongoing processing

Learners in Experiment 1 showed evidence that if referents were available during the presentation of the word, learning occurred during periods of lexical processing (competition). However, processing does not end at stimulus offset; instead, it continues until competition resolves. Indeed, in the delay condition of Experiment 1, all learning is based on the outcome of this continued processing, as no referents were available prior to offset. In the synchronous condition, little learning could occur during these late processing periods, as the next trial initiated shortly after the auditory stimulus ended. However, the potential for additional competition resolution could alter what associations are formed. First, if a dynamic learning system continues to update learned representations as the activation profile of the stimuli being processed continues, the spurious associations formed during early lexical coactivation could be ameliorated after competition resolves. Similarly, if learning always occurs at the end of the learning trial, additional post-trial time to continue processing can allow learned representations to reflect the post-competition activation.

Learning during this post-stimulus period would require that learners form and update associative links on the basis of working memory representations (or simply sustained activation states) of both the visual and auditory stimuli; after the stimuli complete, some memory of their forms must be retained as the learner will receive no more sensory information to support them. Note that in invoking working memory here we are not making the claim that listeners are offloading representations from a lexical processing system to a separate working memory system; rather working memory is more likely embedded within lexical processing by just sustaining activation for the word (e.g., McClelland & Elman, 1986).

More importantly, however, to the extent that the activation of the stimulus endures, this would provide an opportunity to continue learning on the basis of this activation. This working-memory-based learning is the central form of learning in the delay condition of Experiment 1 as well. Experiment 2 extends this to ask whether such learning based on post-competition working-memory representations of the visual stimuli overcomes the formation of spurious associations that arise during synchronous presentation from multiple co-active candidates. This is accomplished by adding a delay to the end of synchronous trials, after auditory and visual stimulus offsets. During this delay, if the visual stimuli are being maintained in memory, they will provide the opportunity to update associations as competition resolves. As competition resolves, learning can operate on the post-competition word-form activations that were the basis of learning in the delay condition. This was not possible in Experiment 1 because the onset of the next trial would have disrupted any updated learning.

Methods

Participants

Thirty participants from the same participant pool as Experiment 1 contributed data to the analysis for Experiment 2. Data from an additional eight participants were not included in the Experiment 2 data because these participants fell below the 75% accuracy threshold for either onset or offset competitor trials during the VWP portion of the study.

Procedure

Experiment 2 was identical to Experiment 1 in all facets except for the timing during the word-referent training trials. As in the synchronous condition of Experiment 1, auditory and visual stimuli were presented simultaneously, starting 100 ms after the participant initiated the trial; the visual stimuli remained on the screen for 800 ms, after which the screen was blank. However, unlike the synchronous condition of Experiment 1, in Experiment 2 the blank screen period lasted 1,550 ms (which was 1,000 ms longer than in Experiment 1). This afforded participants a long period to update their learned associations after competition resolves – nearly twice as much time elapsed after visual stimulus offset as during visual presentation. All other aspects of all tasks remained the same between the experiments, and the same stimuli were used in both.

Analysis

Results from Experiment 2 were compared to the synchronous participants in Experiment 1. This comparison is ideal as these two groups had identical stimulus presentation until the post-trial interval, and because the synchronous group showed enhanced competitor effects, making them the logical comparison to see whether continued processing decreased these spurious associations. All analyses followed the same format as those in Experiment 1, and the same model structure was used (the fixed factors were timing condition during training (synchronous: −.5; Experiment 2: +.5) and word type (onset competitor: −.5; offset competitor: +.5), and participant and auditory word were included as random intercepts – more complex models including random slopes did not provide a better fit to the data by χ2 test; p>.1).

Results

Overall learning

As in Experiment 1, we began by examining the overall efficacy of learning to ensure that potential changes in competitor effects could not arise because of poorer overall learning in one group or the other. Figure 6 suggests on interim test trials, participants learned the word/object mappings very well, and perhaps slightly better than the synchronous group of Experiment 1. A logistic mixed effects model (Table 3) showed a main effect of block (p<.0001), as participant performance improved throughout training. The interaction of word type and block was marginally significant (p=.064), as offset competitors reached ceiling slightly more quickly. No other effects approached significance (all p>.15). Performance at the last block was very close to ceiling in all conditions (M=.98); attempts to model accuracy for this final block resulted in erratic behavior, as there was very little variability in performance.

Figure 6.

Proportion of correct responses during the interim testing trials across blocks of training. A) Onset competitor items. B) Offset competitor items.

Table 3.

Results from analyses of accuracy during interim and VWP trials, comparing Experiment 2 to the synchronous group from Experiment 1. Significant effects are in bold.

| Model | Comparison | B | SE | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy during interim trials for Experiment 2 | Block | .55 | .057 | 9.77 | <.0001 |

| Timing condition | .71 | .50 | 1.42 | .16 | |

| Word type | −.29 | .37 | −.78 | >.2 | |

| Block × timing | −.045 | .11 | −.40 | >.2 | |

| Block × type | .21 | .11 | 1.85 | .064 | |

| Timing × type | .10 | .72 | .14 | >.2 | |

| Block × timing × type | .20 | .22 | .92 | >.2 | |

| Accuracy during VWP trials for Experiment 2 | Timing condition | −.15 | .25 | −.60 | >.2 |

| Word type | .48 | .17 | 2.87 | .0041 | |

| Timing × type | −.22 | .25 | −.90 | >.2 |

Analysis of accuracy during the VWP trials (Table 3) showed that both groups were quite close to ceiling (Msynchronous=.99; MExperiment2=.99); the groups did not reliably differ (p=.55); and there was no interaction of timing condition with word type (p=.37). As in Experiment 1, there was a significant effect of word type (p=.0041), as participants were less accurate for onset competitors (M=.98) than for offset competitors (M=.99).

Analysis of target looks (Figure 7) showed greater and more robust looking to the target in the synchronous condition than in this experiment. Again we used the empirical logit transform of average looks to the target across the analysis window (500–1500 ms). This analysis revealed a main effect of timing condition (B=−.16, SE=.069, t(58.0)=−2.26, p=.028), with fewer target looks by participants in Experiment 2 than by the synchronous group in Experiment 1. There was also a main effect of word type (B=.11, SE=.019, t(6.0)=5.80, p=.0012), with the expected increase in target looks for offset competitor items. There was no interaction (B=−.011, SE=.029, t(411.7)=−.38, p=.70). As in Experiment 1, the synchronous group showed greater looks to the target, suggesting that any increase in competitor fixations for this group cannot be explained by poorer learning of the correct word-referent associations.

Figure 7.

Raw proportion of looks to the target object across time, comparing participants from the synchronous condition of Experiment 1 to participants in Experiment 2. A) Onset competitor trials. B) Offset competitor trials.

Competition

As in Experiment 1, the critical analysis focused on the degree to which participants considered the referent of the phonological competitor of the target word during the VWP trials. We computed log-odds ratios of looks to the competitor item compared to the average of looks to the two unrelated items from 500 to 1500 ms after stimulus onset, exactly as in Experiment 1.

In this analysis (Figure 8, Table 4), the synchronous group exhibited greater competitor effects than participants in Experiment 2 (p=.030); the extra processing time mitigated spurious associations that could have formed from incremental learning during lexical processing. There was also the expected main effect of word type (p=.038), with greater competitor effects for onset competitors than for offset competitors. However, as in Experiment 1, the interaction with competitor type was not significant (p=.53).

Figure 8.

Log odds ratios of competitor effects in Experiment 2. A) Log odds ratio for onset competitor trials across time. B) Log odds ratio for offset competitor trials across time. C) Mean log odds ratio during analysis window by competitor type and timing condition. Error bars are the standard error of the mean.

Table 4.

Results from analyses of competitor effect during VWP trials comparing Experiment 2 to synchronous participants from Experiment 1. Significant effects are in bold.

| Comparison | B | SE | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | .14 | .020 | 11.7 | 7.11 | <.0001 |

| Timing condition | −.077 | .035 | 57.5 | −2.22 | .030 |

| Word type | −.088 | .033 | 6.0 | −2.65 | .038 |

| Timing × type | .033 | .052 | 406.6 | 0.63 | >.2 |

Discussion

Experiment 2 demonstrated reduced competitor effects when training included additional time over which learners could continue to suppress competitors, compared to training in which the following trial began fairly quickly after stimulus offset, before competitors could be fully suppressed (the synchronous condition from Experiment 1). This pattern suggests that although learning can occur during periods of competition, additional time to update learned associations as competition resolves can reduce spurious associations between phonological competitors and the visible referent. After the offset of the stimulus, the learner can continue suppressing competitors and altering learned associations to reflect the later state of processing. Paired with the results of Experiment 1, this suggests that while learning can occur during competition (when multiple associative targets are coactive), it can also continue as processing proceeds, on the basis of working memory representations of the stimuli. Unsupervised associative learning may not occur a single time per learning event, but instead may happen across the events unfolding both in the world and in working memory. Increased processing time allows competition to resolve and reduces spurious learning.

Experiment 3: Interactions of visual and auditory processing

Experiments 1 and 2 emphasized the way that auditory words are processed across time. Meanwhile, visual information may also influence the way auditory stimuli are processed. As a person scans a visual scene, they can use the information to constrain possible interpretations of upcoming auditory information (Chen & Mirman, 2012; Ramscar, Yarlett, Dye, Denny, & Thorpe, 2010). For example, early word learners use mutual exclusivity to identify potential referents of new words (Markman & Wachtel, 1988); if a child sees a stuffed dog (and knows the word dog already) and an unknown toy and is told to choose the “dax,” the child is likely to pick the unknown toy – her knowledge that the dog is not called a “dax” lets her interpret the novel word as the name of the unknown toy. Ramscar and colleagues (2010) showed that this type of prediction of the upcoming name of an item can help learners acquire word-referent mappings more quickly (although this paper did not address real-time competition processes).

Such expectations could play a similar role in constraining the activation of competitor words in a novel word learning situation. If the learner sees two objects (e.g. a goba and a pacho) and has some idea of their labels, she can boost activation of goba and pacho before any auditory information is received. If the auditory stimulus then starts with go-, activation for goba has a boost relative to gonu, allowing more rapid resolution of the ambiguity. The context of the task thus provide clues to the upcoming auditory stimulus, as long as the learner has some knowledge of the correct word-referent mappings (Yurovsky, Fricker, Yu, & Smith, 2014). This speeded competition resolution will thus improve as learning proceeds – the better the learner knows the correct word-referent mappings, the better she can pre-activate the possible upcoming stimuli, and the quicker she can suppress activation of the competing word-form.

In the previous experiments, pre-activation of the upcoming words was not possible: the visual stimuli never preceded the auditory, so participants did not have the requisite time to start forming expectations. In Experiment 3, during the learning phase, we presented the visual stimuli first, to allow time for the learners to take in this information to form expectations about the upcoming auditory stimulus. That is, the timing of presentation in this experiment allowed time for the dynamics of visual processing more time to unfold, to maximally affect lexical processing dynamics.

Methods

Participants

Data from 30 participants selected from the same participant pool as the previous experiments were included in analysis of Experiment 3. Data from an additional seven participants were excluded because they did not reach the 75% accuracy threshold for either onset or offset competitors during the VWP trials. Due to computer error, three included participants did not receive the full 320 VWP trials.

Procedure

The stimuli and design were identical to the previous experiments in all aspects except the timing of the word-referent training trials. On these trials, visual stimulus presentation began 100 ms after the participant clicked the dot to initiate the trial. After 1000 ms of visual display, the auditory stimulus began. The visual stimuli remained on the screen for an additional 800 ms after auditory stimulus onset, and then the screen was blank for a 550 ms inter-trial interval.

Analysis

Data from Experiment 3 were compared against data from the synchronous condition from Experiment 1; other than the visual pre-scan, these two groups had identical stimulus timing, including visual presentation present during auditory stimuli, and a rapid transition to the succeeding trial after auditory offset. Additionally, this comparison affords the clearest means of investigating whether visual processing dynamics mitigate the formation of spurious associations during lexical activation. The same model structure was used as in previous studies; more complex models did not improve model fit (all p>.13).

Results

Overall learning

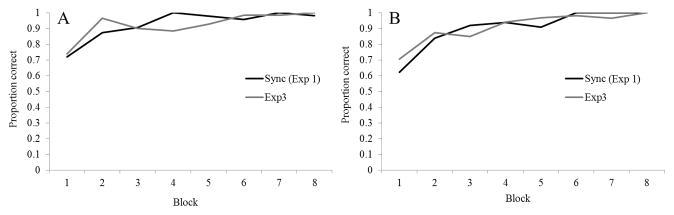

As in the prior experiments, we began by analyzing learning during the interim test trials. As Figure 9 shows learners were highly accurate and did not differ substantively from the synchronous group of Experiment 1. This was confirmed with a logistic mixed model. This showed a main effect of block (p<.0001), with performance improving throughout training. No other main effects or interactions approached significance (all p>.15), signaling a quite similar timecourse of learning between the groups and the word types. On the final block of interim trials, accuracy was extremely high (M=.995); participants in Experiment 3 were all at ceiling in this block, as were all synchronous participants for offset competitor items. These highly accurate levels of performance precluded statistical analysis of the final block.

Figure 9.

Proportion of correct responses during the interim testing trials, comparing participants in the synchronous condition of Experiment 1 to participants in Experiment 3. A) Onset competitor trials. B) Offset competitor trials.

Accuracy during the VWP trials was also high for both groups (Msynchronous=.99; MExperiment3=.97). This difference approached significance (p=.064); however, the Experiment 3 participants performed more poorly than the synchronous participants from Experiment 1, so any increased competition by the synchronous group can’t be attributed to poorer overall learning. There was also a main effect of word type (p=.022), with higher accuracy for offset competitors. The interaction was not significant (p=.37).

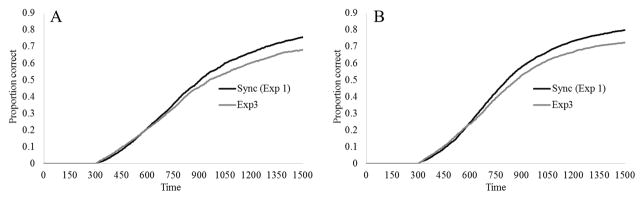

Analysis of target looks (Figure 10) used the empirical logit transform of average looks to the target during the analysis window (500–1500 ms), as in the previous experiments. The two groups did not differ in target fixations (B=−.13, SE=.086, t(58.0)=−1.55, p=.13), counter to predictions that the synchronous group might have learned the correct target-referent associations more poorly. There was a main effect of word type (B=.11, SE=.017, t(6.0)=6.65, p=.00056), with more target looks for offset competitor trials than for onset competitor trials. There was no interaction (B=−.0078, SE=.030, t(410.8)=−.26, p=.79).

Figure 10.

Raw proportion of looks to the target object across time, comparing participants in the synchronous condition of Experiment 1 to participants in Experiment 3. A) Onset competitor trials. B) Offset competitor trials.

As in the previous experiments, there was no evidence that the synchronous group learned the words more poorly than participants in Experiment 3. Thus increased competitor effects for this group could not emerge as a result of poorer learning.

Competition

Figure 11 shows the critical analysis of competitor effects, again showing increased fixations in the synchronous group. Our statistical analysis (Table 6) again used the log-odds ratio of looks to the competitor item versus looks to the average of the two unrelated items during the analysis window (500–1500 ms). Two cases from Experiment 3 produced log-odds ratios of positive or negative infinity, and so were excluded from analysis.

Figure 11.

Log odds ratios of competitor effects for Experiment 3. A) Log odds ratio for onset competitor trials across time. B) Log odd ratio for offset competitor trials across time. C) Mean log odd ratios during analysis window by competitor type and timing condition. Error bars signify the standard error of the mean.

Table 6.

Results from analyses of competitor effect during VWP trials comparing Experiment 3 against the synchronous group of Experiment 1. Significant effects are in bold.

| Comparison | B | SE | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | .15 | .023 | 10.8 | 6.36 | <.0001 |

| Timing condition | −.072 | .035 | 58.2 | −2.05 | .045 |

| Word type | −.086 | .039 | 6.0 | −2.22 | .069 |

| Timing × type | .035 | .050 | 406.6 | .70 | >.2 |

This analysis revealed a significant effect of timing condition (p=.045), with greater competitor effects for the synchronous participants from Experiment 1 than for the Experiment 3 participants. That is, the visual pre-scan period decreased the magnitude of competitor effects. The expected significant effect of word-type approached significance (p=.069), with marginally greater competitor effects for onset competitors. As in the prior experiments, the interaction was not significant (p=.48).

Discussion

When learners were given an opportunity to preview and process the visual stimuli before auditory stimulus presentation, the magnitude of competitor effects was decreased relative to participants with no such pre-scan. This decrease emerged despite the simultaneous availability of words and visual referents in the preview group (which should have promoted lexical competition was unfolding). Additionally, both groups received the same amount of time post-stimulus before the next trial began, so the Experiment 3 participants had no opportunity to continue resolving competition. Instead, it appears that the presence of the visual stimuli before auditory onset impacted auditory processing, such that competitor words were more readily suppressed.

This finding argues for an interaction between visual processing and auditory processing (Ramscar et al., 2010). Specifically, as a learner processes a visual display, visual information constrains auditory processing to emphasize the relevant word forms (see also, Chen & Mirman, 2012). The learner can form expectations that the upcoming auditory stimulus will be the name of one of the two displayed items, allowing rapid suppression of a competitor word that does not match the display. However, these expectations require that the learner has some idea what the word-referent mappings are; without this knowledge, she has no way to predict that “gonu” is a more likely auditory stimulus than “goba” on a trial where the gonu is present. This requires a nuanced interplay between timescales of learning and processing: the state of knowledge of the correct word-referent mappings affects the way that expectations can be formed about upcoming auditory stimuli; these expectations affect the way that competition dynamics play out during auditory processing; and the nature of these auditory processing dynamics impact the updated learned associations between words and referents (see Yurovsky, Fricker, Yu, & Smith, 2014 for a similar account of partial knowledge constraining word learning though without the critical real-time interactions we demonstrate here). Early in learning, learners would be predicted to have little ability to form useful expectations of the upcoming auditory stimulus, and so should be more susceptible to spurious associations with competitors. The present design does not allow direct investigation of this effect, as analysis is predicated on having primarily correct trials by test. Instead, further research with other testing regimes is needed in the future.

Combined Statistical Analysis

The analyses of Experiments 2 and 3 compared the participants in those experiments against the data from the synchronous condition of Experiment 1. However, these may be better considered as separate conditions of a single experiment, as all comparisons are conducted against the same reference group. The experiments were presented separately as they address different theoretical questions. However, an omnibus analysis including all conditions together may be more statistically appropriate. We conducted this analysis to confirm that the effects presented held when using this more standard approach. For this analysis, we combined the log-odds ratios for competitor effects across conditions. We included condition (synchronous, delay, Experiment 2 and Experiment 3; dummy coded with synchronous as the reference group) and word-type (onset competitor: −.5; offset competitor: +.5) as factors, and random intercepts of participants and auditory word. As in the independent models used for each experiment, more complex models did not improve model fit by χ2 test (p>.85).

This analysis confirmed the findings from the independent models (Table 7). Specifically, every condition showed a significantly larger competitor effect compared to the synchronous group (all p<.033), and there was a significant effect of word-type, with greater competitor effects for onset competitors. The interaction of condition and word-type was not significant for any comparison. This analysis thus confirms the findings detailed above, and ensures that effects were not a result of the statistical approach used.

Table 7.

Results from analyses of competitor effect during VWP trials comparing all experiments in a single omnibus model. The synchronous group from Experiment 1 served as the reference group. Significant effects are in bold.

| Comparison | B | SE | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | .18 | .026 | 48.8 | 7.0 | <.0001 |

| Sync vs. delay | −.10 | .033 | 114.0 | −3.2 | .0020 |

| Sync vs. Exp 2 | −.077 | .033 | 113 | −2.3 | .022 |

| Sync vs. Exp 3 | −.072 | .033 | 113.8 | −2.2 | .033 |

| Word-type | −.11 | .040 | 66.2 | −2.8 | .0064 |

| Delay × word type | .015 | .049 | 818.4 | .31 | .75 |

| Exp 2 × word type | .033 | .049 | 816.5 | .67 | .50 |

| Exp 3 × word type | .054 | .052 | 551.7 | 1.05 | .30 |

Alternatively, effects from Experiments 2 and 3 could be compared against the delay condition of Experiment 1; this would allow investigation of whether the different timing manipulations showed the same impact on competitor effects, and if they led to different patterns of effects for the two timing conditions. We conducted the same model as above, but using the delay condition as the reference group. Neither Experiment 2 nor Experiment 3 differed significantly from the delay group, and no interactions with word-type were attested (all t < 1). Further, comparisons between Experiment 2 and Experiment 3 showed no difference in the size of competitor effects and no interaction with word-type. Thus the delay conditon and Experiments 2 and 3 led to a similar reduction in the competitor effects, and similar effects for both word types (perhaps each of these manipulations reduced spurious associations to floor, leading to the extremely similar levels of effects). Future research is needed to determine whether these manipulations differentially impact the formation of spurious associations. Specifically, we predict that the visual preview manipulation of Experiment 3 may lead to a different timecourse of the elimination of competitor effects, as it relies on partial knowledge of the mappings to block coactivation.

Differences in the Quality of Learned Representations

An important concern across studies is whether these differences in competition simply reflect differences in how well words were learned in the two conditions. Our initial hypothesis was that more poorly learned words would exhibit more competition. Thus, in each of the previous experiments, care was taken to ensure that the synchronous group’s increased competitor effects did not arise because they had learned the words more poorly than the delay group. However, it is also possible that better learning by the synchronous group could elicit larger competitor effects4. If learners in this group established stronger word-referent mappings, then the facility with which they fixated referents matching the acoustic stimulus during the VWP trials should be improved. This would lead to more ready target fixations (as was attested in Experiments 1 and 2); however it may also lead to increased consideration of partially matching referents early in the activation process. That is, participants in the synchronous group might have shown larger competitor effects because their stronger word-referent mappings sped the activation dynamics.

Looking across experiments at our three measures of learning quality (accuracy on the interim testing trials, accuracy on the VWP trials, and fixations to the target on the VWP trials) there is mixed evidence for differences in the overall quality of learning (Table 8). The two accuracy measures either show a numerically small disadvantage for synchronous training (Exp. 1, interim testing), or a marginal advantage for it (Exp. 2, VWP accuracy). The target fixation measure, however, is slightly more consistent, showing significantly or marginally more fixations for synchronous learners in two experiments. Thus, it is important to address the possibility that synchronous words were learned better, which in turn gives rise to greater competitor fixations.

Table 8.

Summary of results on quality of learning across three experiments. Significant effects are marked with *, marginal effects with +.

| Accuracy | Efficiency Target Fixations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Interim Testing | VWP | ||

| Exp 1 | Sync poorer * | ø | Sync faster + |

| Exp 2 | ø | ø | Sync faster * |

| Exp 3 | ø | Sync better + | ø |

To investigate this possibility, we examined the basic assumption that better learning leads to more competition. Thus, we examined the relationship between the level of learning and the degree of competitor effects across the three studies. If effects arise because of degree of learning rather than because of timing condition, then timing condition should be irrelevant to competitor effect size, but better learning should yield stronger competitor effects. We conducted several additional analyses to determine whether those who learned better also showed greater competitor effects. These analyses used accuracy on the interim trials and/or the VWP trials as our measure of learning. This was done (rather than the target fixations measure) for several reasons. First, it is the most direct measure of learning – fixations to the target also reflect oculomotor and visual-cognitive factors (Farris-Trimble & McMurray, 2013). Second, target fixations are not independent of competitor fixations; if learners are looking at the target, they cannot be simultaneously looking at competitors.

We present a representative analysis below. Several additional analyses are available in the Online Supplement. These analyses uniformly showed no such relationship; even when comparing the poorest to the best learners, the degree of learning was substantially less predictive of competitor effect sizes than was timing condition, and in many cases better learners showed smaller competitor effects.

Representative Analysis

Determining how well a learner has acquired a word-referent mapping is difficult; despite two learners reaching ceiling performance, they may have sub-threshold differences in how well they have learned the mappings. Although we can’t state unequivocally that all participants who are at 100% accuracy learned equally well, we can be fairly sure that those at ceiling learned better than those off ceiling – those making multiple errors clearly haven’t learned the mappings as well as those making none. The primary analyses presented above (as well as those presented here) excluded participants who make a large number of errors for practical reasons: we need a large number of accurate trials for reliable eye-movement data. However, even among those who passed our accuracy threshold, there was variability in performance, allowing us to examine whether participants who learned the mappings better showed greater competitor effects than participants who learned the mappings more poorly.