Abstract

Background:

Dementia results in changes in cognition, function, and behavior. We examine the effect of sociodemographic and clinical risk factors on cognitive, functional, and behavioral declines in incident dementia patients.

Methods:

We used longitudinal data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center to evaluate cognitive (Mini-Mental State Exam [MMSE]), functional (Functional Activities Questionnaire [FAQ]), and behavioral (Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire [NPI-Q] severity score) trajectories for incident dementia patients over an 8-year period. We evaluated trajectories of 457 patients with mixed effects linear regression models.

Results:

In the first year, cognition worsened by −1.518 (95% confidence interval [CI] −1.745, −1.291) MMSE points (0–30 scale). Education, race, and region of residence predicted cognition at diagnosis. Age of onset, geographic region of residence, and history of hypertension and congestive heart failure predicted cognitive changes. Function worsened by 3.464 (95% CI 3.131, 3.798) FAQ points in the first year (0–30 scale). Cognition, gender, race, region of residence and place of residence, and a history of stroke and hypercholesterolemia predicted function at diagnosis. Place of residence and a history of diabetes predicted functional changes. Behavioral symptoms worsened by 0.354 (95% CI 0.123, 0.585) NPI-Q points in the first year (0–36 scale). Age of onset, region of residence, and history of hypertension and psychiatric problems predicted behaviors at diagnosis. Cognition explained changes in behavior.

Conclusions:

Sociodemographic characteristics and clinical comorbidities predict cognitive and functional changes. Only cognitive status explains behavioral decline. Results provide an understanding of the characteristics that impact cognitive, functional, and behavioral decline.

Keywords: Dementia, Alzheimer’s, Health services, Public health

Dementia is a complex neurodegenerative disease that affects over 5 million Americans (1). The defining clinical features of dementia include progressive declines in cognitive and functional ability and a wide range of challenging behavioral symptoms that occur throughout the disease process (2). Although all persons with dementia experience cognitive, functional, and behavioral changes, transitions over time are not uniform (3). Understanding which predictors accelerate or decelerate decline can help providers and families better prepare for caring of individuals with dementia. Unfortunately the factors that affect changes in newly diagnosed dementia patients are poorly understood.

Previous studies evaluating cognitive, functional, and behavioral trajectories have significant limitations including limited patient follow-up, combined incident and prevalent cases, failure to account for attrition, and evaluating functional decline and behavioral symptoms independent of cognitive status despite evidence of their interrelatedness (3–7). Furthermore, these prior studies focused primarily on biomedical predictors of decline (eg, vascular risk factors) and largely ignored sociodemographic characteristics including race, marital status, geographical region, and place of residence. Although these elements are risk factors for developing dementia, there is limited research concerning their impact on decline following a dementia diagnosis (1,8,9).

Our study seeks to identify predictors of cognitive, functional, and behavioral declines in a diverse sample of newly diagnosed dementia patients. This study fills an important void in the literature by evaluating the role of dementia risk factors on decline after disease onset. We conducted an exploratory data analysis to evaluate the impact of sociodemographic and clinical risk factors on trajectories for cognition, function, and behavioral symptoms. Results may assist in care planning and help to focus future interventions on those factors that have the greatest effect on decline on these three areas.

Methods

Study Setting and Participants

We used data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) that serves as a data hub for 34 past and present Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs) (10). Patients are enrolled in ADCs by clinical referral, self-referral, and active ADC recruitment. Depending on the ADC, a single clinician or consensus panel makes a dementia diagnosis. ADCs attempt to follow all patients annually using a standardized protocol that includes cognitive, functional, and behavioral assessments. During annual assessments, trained ADC clinicians and staff administer the data collection protocol in person or over the phone to obtain data from patients and informants (eg, spouse). The NACC combines patient data across ADCs in a publicly available longitudinal file called the Uniform Data Set (UDS) (10).

For this study, we used the UDS (March 2015 data freeze) and limited our analysis to newly diagnosed individuals >70 years old (ie, incident dementia cases; Appendix Figure 1) (11). To be identified as an incident case, NACC had to observe a patient progressing from not having a dementia diagnosis to having a dementia diagnosis. Although the UDS provides diagnostic categories (eg, Alzheimer’s dementia), we did not limit our analysis to a specific type of dementia because diagnosis is subject to a high degree of misclassification (12–14). To evaluate disease progression over time within an individual and to account for nonlinear change, we further limited our analysis to individuals with at least two observations post dementia diagnoses. Finally, we required individuals to have complete observations on variables of interest for their first observation.

Measures of Dementia

The progression of dementia was assessed in terms of cognition, function, and behavior as these are the defining clinical features of the disease (2). During annual ADC assessments, cognitive status was measured using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (15). The MMSE was completed by clinicians and scored from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating greater cognitive impairment. Functional ability was assessed using the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ). The FAQ was administered by clinicians to informants and was scored from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater functional impairment (16). Behavioral symptoms were assessed using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q). The NPI-Q was administered by clinicians to informants and was scored from 0 to 36, with higher scores indicating greater severity of behavioral symptoms (17).

Explanatory Variables

Sociodemographic risk factors available in the UDS include age at the time of diagnosis, gender, educational attainment, race, marital status, geographic region, and place of residence (community facility). Clinical risk factors include self-reported history of hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure, stroke, hypercholesterolemia, or psychiatric problems. All covariates except place of residence in the previous observation and marital status were coded as time invariant.

Statistical Analysis

We used separate linear-mixed effects models to evaluate cognitive, functional, and behavioral trajectories of incident dementia patients. We initially constructed simple models where time, measured as years since a diagnosis of dementia, was the only predictor of change. To evaluate nonlinear trajectories and individual deviation from the population mean trajectory, we tested the inclusion of a squared term for time and random effects terms for both intercepts and slopes. Akaike information criterion was used as a measure of fit to determine the best fitting simple models. Based on our analysis of the simple models, all models included a term for time-squared and a random intercept and random slopes for both the linear and quadratic terms (Appendix Equation 1).

We extended this preliminary model to estimate the association between dementia risk factors and cognitive, functional, and behavioral change. Because previous models did not evaluate the effect of both sociodemographic and clinical factors on change and due to our a priori interest in their associations, we included main effects (ie, not interacted with time) for these predictors regardless of statistical significance. In models evaluating functional and behavioral trajectories, cognitive status was also included as a time-varying main effect. The functional and behavioral models also controlled for informant type (eg, spouse), as these measures are based on informant input. We then used a model-building approach (described below) to determine the inclusion of interactions between sociodemographic and clinical predictors with time (ie, slope effects). We did not evaluate interactions with time-squared because preliminary analyses examining these interactions resulted in poor fit (eg, wild fluxuations in the tails of predicted functional trajectories that are not representative of measurement error or normal variation). Poor model fit appeared to reflect sparse data over time for certain combinations of covariates. The model-building process began with a model that included all predictors and the interaction of all predictors with time. Interactions with an α > 0.10 were identified as potentially poor fitting and candidates for exclusion. Using the likelihood ratio test, we tested the reduced model (ie, the model without the interaction) against the full model (ie, the model with the interaction term). We retained the full model if the p value of the likelihood ratio test was <0.05. This strategy allowed for nonsignificant interactions to remain in the model if their inclusion resulted in a better fitting model. To aid in the comparison of trajectories, we also used the final models to estimate the effect of covariates on standardized cognitive, functional, and behavioral decline (ie, where only the outcome variable is standardized by subtracting the mean value at baseline from an individual’s observed value and dividing by the baseline standard deviation). All analyses excluded individuals who requested not to participate in follow-up assessments (ie, dropouts; n = 96) as they had higher cognitive scores at the time of diagnosis (Appendix Table 1). In a sensitivity analysis, we included these individuals in our final models.

Using the final models, we predicted the annual rate of change by year and trajectories over 8 years. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 12.1 (College Station, Texas).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the 457 individuals who met the study inclusion criteria, the mean age of individuals in the analytic sample at the time of diagnosis was 79 years, 55% were male, and 8% were African American (Table 1). Due to few observations, American Indians, Alaskan Natives, Native Hawaiians, Asians, and individuals who identified as multiracial were grouped in the “other” racial category. At the time of diagnosis, the mean MMSE score was 24.22 (SD 3.24) and 97% of individuals had a global Clinical Dementia Rating score of very mild or mild dementia.

Table 1.

Baseline Sample Characteristics

| N = 457 | |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, y; M (SD) | 79.91 (6.26) |

| Male, N (%) | 251 (55) |

| Years of education, M (SD) | 15.37 (2.91) |

| Race | |

| White, N (%) | 396 (87) |

| African American, N (%) | 39 (8) |

| Other, N (%)* | 22 (5) |

| Martial status at diagnosis | |

| Married, N (%) | 327 (71) |

| Widowed, N (%) | 100 (22) |

| Other, N (%) | 30 (7) |

| Region of residence | |

| Northeast, N (%) | 85 (19) |

| South, N (%) | 28 (6) |

| West, N (%) | 120 (26) |

| Midwest, N (%) | 51 (11) |

| Not specified, N (%) | 173 (38) |

| Place of residence at diagnosis | |

| Community dwelling, N (%) | 440 (96) |

| Facility, N (%) | 17 (4) |

| Informant relationship | |

| Spouse, N (%) | 291 (64) |

| Other family member, N (%) | 129 (28) |

| Other, N (%) | 37 (8) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Ever hypertension, N (%) | 311 (68) |

| Ever diabetes, N (%) | 64 (14) |

| Ever congestive heart failure, N (%) | 29 (6) |

| Ever hypercholesterolemia, N (%) | 316 (69) |

| Ever stroke, N (%) | 47 (10) |

| Ever psychiatric problems, N (%) | 50 (11) |

| MMSE at diagnosis, M (SD) | 24.22 (3.24) |

| FAQ at diagnosis, M (SD) | 10.89 (7.12) |

| NPI-Q at diagnosis, M (SD) | 3.90 (3.99) |

| Clinical Dementia Rating score | |

| None, N (%) | 0 (0.00) |

| Very mild, N (%) | 275 (60.18) |

| Mild, N (%) | 171 (37.42) |

| Moderate, N (%) | 11 (2.41) |

| Severe, N (%) | 0 (0.00) |

| Number of follow up visits, M (SD)† | 4.13 (1.20) |

Note. MMSE = Mini-Mental State Exam; FAQ = Functional Activities Questionnaire; NPI-Q = Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire.

*Other racial category is comprised of American Indians, Alaskan Natives, Native Hawaiians, Asians, and individuals who identify as multiracial.

†Thirty-nine percent of the sample had 3 observations; 27% of the sample had 4 observations; 19% of the sample had 5 observations; and 15% of the sample had >5 observations.

Cognitive Trajectories

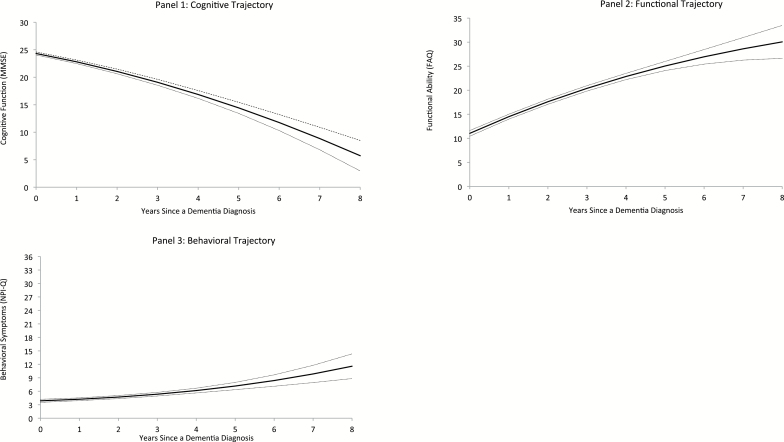

As noted above, all models contained main effects for sociodemographic and medical predictors. The best fitting cognitive model included additional terms for the interaction of age of onset, region of residence, hypertension, and congestive heart failure with time (Appendix Equation 2). Holding all variables in the fully adjusted model at their sample mean, the average rate of cognitive decline in the first year was −1.518 (95% CI: −1.745, −1.291) MMSE points (Table 2). As depicted in Figure 1A, the rate of cognitive decline accelerated over time.

Table 2.

Average Rate of Change by Year

| Year | Cognition—MMSE (95% CI) | Function—FAQ (95% CI) | Behavior—NPI-Q (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis–Year 1 | −1.518 (−1.745, −1.291) | 3.464 (3.131, 3.798) | 0.354 (0.123, 0.585) |

| Year 1–Year 2 | −1.748 (−1.914, −1.583) | 3.111 (2.898, 3.322) | 0.485 (0.338, 0.632) |

| Year 2–Year 3 | −1.979 (−2.173, −1.785) | 2.778 (2.584, 2.972) | 0.637 (0.483, 0.792) |

| Year 3–Year 4 | −2.209 (−2.495, −1.923) | 2.467 (2.156, 2.778) | 0.811 (0.558, 1.064) |

| Year 4–Year 5 | −2.440 (−2.840, −2.040) | 2.178 (1.700, 2.660) | 1.007 (0.624, 1.391) |

| Year 5–Year 6 | −2.671 (−3.193, −2.148) | 1.911 (1.234, 2.588) | 1.225 (0.695, 1.754) |

| Year 6–Year 7 | −2.901 (−3.549, −2.253) | 1.666 (0.775, 2.557) | 1.464 (0.776, 2.152) |

| Year 7–Year 8 | −3.132 (−3.907, −2.356) | 1.441(0.319, 2.564) | 1.724 (0.867, 2.582) |

Notes. MMSE = Mini-Mental State Exam; FAQ = Functional Activities Questionnaire; NPI-Q = Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire. Estimates are based on the fully adjusted trajectory model holding covariates at their sample mean. Negative MMSE slopes represent a decline in cognitive ability. Positive FAQ slopes represent a decline in functional ability. Positive NPI-Q slopes represent an increase in behavioral symptoms.

Figure 1.

Fully adjusted model trajectories based on sample mean values for covariates (dashed lines represent 95% CI) of cognition (1), function (2), and behavior (3). Higher MMSE scores indicate greater cognitive abilities. Higher FAQ scores indicate more functional limitations. Higher NPI-Q scores indicate greater severity of behavioral symptoms. CI = confidence interval; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Exam; FAQ = Functional Activities Questionnaire; NPI-Q = Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire.

Results of the mixed effects model evaluating cognitive trajectories are reported in Table 3 (Appendix Table 2 reports standardized cognitive trajectories and the results of the sensitivity analysis that included individuals who dropped out). In the table, negative coefficients indicate a predictor is associated with greater cognitive impairment. At the time of diagnosis, those with less education, African Americans compared with whites and individuals living in the West compared with the Northeast had lower cognitive scores. Older age of onset, residing in the Northeast compared with the West, and a history of hypertension and congestive heart failure were associated with slower decline.

Table 3.

Parameter Estimates of Cognitive Trajectories

| Effects | Unadjusted cognition (MMSE) | Adjusted cognition (MMSE) |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 24.295*** (24.006, 24.585) | 20.328*** (15.849, 24.807) |

| Time | −1.374*** (−1.652, −1.096) | −3.847*** (−6.049, −1.644) |

| Time2 | −0.127*** (−0.193, −0.060) | −0.115*** (−0.181, −0.050) |

| Age of onset (y) | 0.001 (−0.046, 0.048) | |

| Age of onset (y) × Time | 0.031* (0.004, 0.058) | |

| Male | 0.231 (−0.366, 0.827) | |

| Years of education | 0.236*** (0.141, 0.331) | |

| Race (ref = White) | ||

| African American | −1.629** (−2.640, −0.618) | |

| Other | −0.274 (−1.558, 1.010) | |

| Marital status (ref = Widowed) | ||

| Married | −0.582 (−1.241, 0.077) | |

| Other | −0.039 (−1.070, 0.991) | |

| Region of residence (ref = Northeast) | ||

| South | 0.025 (−1.245, 1.294) | |

| West | −1.192** (−2.015, −0.368) | |

| Midwest | 1.197* (0.166, 2.228) | |

| Not specified | −0.192 (−0.971, 0.587) | |

| Region of residence (ref = Northeast) × Time | ||

| South | −0.352 (−1.109, 0.405) | |

| West | −0.743** (−1.239, −0.247) | |

| Midwest | 0.082 (−0.521, 0.686) | |

| Not specified | −0.281 (−0.743, 0.180) | |

| Community dwelling in previous time period (ref = Facility) | 0.474 (−0.393, 1.341) | |

| Ever hypertension | 0.418 (−0.193, 1.029) | |

| Ever hypertension × Time | 0.371* (0.021, 0.721) | |

| Ever diabetes | −0.216 (−1.030, 0.597) | |

| Ever congestive heart failure | 0.207 (−0.923, 1.337) | |

| Ever congestive heart failure × Time | 0.698* (0.031, 1.366) | |

| Ever stroke | −0.315 (−1.145, 0.515) | |

| Ever hypercholesterolemia | 0.249 (−0.362, 0.861) | |

| Ever psychiatric problems | 0.794 (−0.086, 1.674) | |

Notes. N = 457. MMSE = Mini-Mental State Exam (scored 0–30). Higher scores indicate greater cognitive abilities.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Functional Trajectories

The best fitting functional model included additional terms for the interaction of cognition, education, place of residence, and diabetes with time (Appendix Equation 3). Holding all variables in the fully adjusted model at their sample mean, the average rate of functional decline in the first year was 3.464 (95% CI: 3.131, 3.798) FAQ points (Table 2). As depicted in Figure 1B, the rate of functional decline slowed over time.

Results of the mixed effects model evaluating functional decline are presented in Table 4 (Appendix Table 3 reports standardized functional trajectories and the results of the sensitivity analysis that included individuals who dropped out). In the table, positive coefficients indicate a predictor is associated with greater functional limitations. At the time of diagnosis, higher cognitive status, males, African Americans compared with whites, residing in the Midwest compared with the Northeast, living in the community, and having a history of hypercholesterolemia were associated with fewer functional limitations. Place of residence and a history of diabetes had a significant effect on functional decline over time.

Table 4.

Parameter Estimates of Functional Trajectories

| Effects | Unadjusted Function (FAQ) | Adjusted Function (FAQ) |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 10.852*** (10.207, 11.497) | 31.529*** (22.807, 40.251) |

| Time | 3.907*** (3.491, 4.324) | 2.028** (0.574, 3.481) |

| Time2 | −0.235*** (−0.320, −0.149) | −0.279*** (−0.371, −0.187) |

| Cognitive status (MMSE) | −0.404*** (−0.520, −0.288) | |

| Cognitive status (MMSE) × Time | −0.031 (−0.067, 0.004) | |

| Age of onset (y) | −0.016 (−0.101, 0.069) | |

| Male | −2.273*** (−3.375, −1.172) | |

| Years of education | −0.123 (−0.324, 0.077) | |

| Years of education × Time | 0.056 (−0.004, 0.116) | |

| Race (ref = White) | ||

| African American | −3.520*** (−5.329, −1.711) | |

| Other | −0.106 (−2.399, 2.188) | |

| Marital status (ref = Widowed) | ||

| Married | −1.174 (−2.554, 0.207) | |

| Other | −0.326 (−2.153, 1.502) | |

| Region of residence (ref = Northeast) | ||

| South | −0.011 (−2.273, 2.250) | |

| West | 1.779* (0.304, 3.253) | |

| Midwest | −2.221* (−4.046, −0.396) | |

| Not specified | 0.048 (−1.331, 1.427) | |

| Community dwelling in previous time period (ref = Facility) | −4.519*** (−6.890, −2.147) | |

| Community dwelling in previous time period (ref = Facility) × Time | 1.096** (0.359, 1.833) | |

| Informant relationship (ref = Spouse) | ||

| Other family member | −0.944 (−2.210, 0.321) | |

| Other | −1.677 (−3.442, 0.088) | |

| Ever hypertension | 0.018 (−1.074, 1.111) | |

| Ever diabetes | 1.057 (−0.632, 2.746) | |

| Ever diabetes × Time | −0.535* (−1.062, −0.008) | |

| Ever congestive heart failure | 0.307 (−1.704, 2.318) | |

| Ever stroke | 2.214** (0.798, 3.630) | |

| Ever hypercholesterolemia | −1.281* (−2.381, −0.181) | |

| Ever psychiatric problems | −0.710 (−2.288, 0.869) | |

Notes. N = 457. FAQ = Functional Activities Questionnaire (scored 0–30). Higher scores indicate more functional limitations.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Behavioral Trajectories

The best fitting behavioral model included additional terms for the interaction of cognition and stroke with time (Appendix Equation 4). Holding all variables in the fully adjusted model at their sample mean, the severity of behavioral problems worsened by 0.354 (95% CI: 0.123, 0.585) NPI-Q points in the first year (Table 2). As depicted in Figure 1C, the rate of behavioral decline accelerated over time.

Results of the mixed effects model evaluating behavioral trajectories are presented in Table 5 (Appendix Table 4 reports standardized functional trajectories and the results of the sensitivity analysis the included individuals who dropped out). In the table, positive coefficients indicate a predictor is associated with more severe behavioral problems. Age of dementia onset, residing in the South compared with the Northeast, and a history of hypertension and psychiatric problems were significant predictors of an individual’s behavioral score at the time of diagnosis. Only cognitive function had an effect on behavioral trajectories over time.

Table 5.

Parameter Estimates of Behavioral Trajectories

| Effect | Unadjusted Behavior (NPI) | Adjusted Behavior (NPI) |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.839*** (3.481, 4.198) | 10.593*** (5.364, 15.822) |

| Time | 0.461** (0.165, 0.757) | 1.256** (0.488, 2.024) |

| Time2 | −0.001 (−0.068, 0.066) | 0.002 (−0.069, 0.073) |

| Cognitive status (MMSE) | −0.073 (−0.149, 0.003) | |

| Cognitive status (MMSE) × Time | −0.031* (−0.057, −0.006) | |

| Age of onset (y) | −0.081** (−0.134, −0.029) | |

| Male | 0.168 (−0.576, 0.911) | |

| Male × Time | −0.258 (−0.562, 0.046) | |

| Years of education | −0.045 (−0.151, 0.060) | |

| Race (ref = White) | ||

| African American | −0.485 (−1.601, 0.630) | |

| Other | −0.123 (−1.540, 1.295) | |

| Marital status (ref = Widowed) | ||

| Married | 0.100 (−0.814, 1.014) | |

| Other | 0.945 (−0.236, 2.127) | |

| Region of residence (ref = Northeast) | ||

| South | 1.776* (0.383, 3.170) | |

| West | 0.776 (−0.132, 1.685) | |

| Midwest | 0.778 (−0.357, 1.914) | |

| Not specified | 1.269** (0.413, 2.124) | |

| Community dwelling in previous time period (ref = Facility) | 0.846 (−0.111, 1.803) | |

| Informant relationship (ref = Spouse) | ||

| Other family member | 0.112 (−0.810, 1.034) | |

| Other | −0.352 (−1.729, 1.025) | |

| Informant relationship (ref = Spouse) × Time | ||

| Other family member | −0.304 (−0.627, 0.019) | |

| Other | −0.420 (−0.894, 0.054) | |

| Ever hypertension | 0.738* (0.064, 1.413) | |

| Ever diabetes | 0.520 (−0.375, 1.415) | |

| Ever congestive heart failure | 0.624 (−0.616, 1.864) | |

| Ever stroke | 1.121 (−0.156, 2.398) | |

| Ever stroke × Time | −0.516 (−1.064, 0.032) | |

| Ever hypercholesterolemia | −0.617 (−1.291, 0.056) | |

| Ever psychiatric problems | 1.319** (0.346, 2.291) | |

Notes. N = 457. NPI-Q = Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire severity score (scored 0–36). Higher scores indicate more severe behavioral symptoms.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Discussion

Our objective was to examine the rates of decline over 8 years for three defining clinical features of dementia (cognition, function, and behavior) in newly diagnosed dementia patients. Previous studies have shown the effect of sociodemographic characteristics and medical history on the risk of developing dementia (8,9). However few studies have explored whether these same risk factors influence decline once individuals have a dementia diagnosis. Our study is a step toward filling that void and expends on previous efforts to identify predictors of decline.

Consistent with other studies, our results indicate that African Americans compared with whites have greater cognitive impairment at the time of diagnosis. In our study, African Americans and whites have similar ages at the time of diagnosis, indicating African Americans may develop dementia at earlier ages. Others have noted that African Americans are more likely to be diagnosed later in the course of the disease and have a higher prevalence of dementia at all ages compared with whites (8,18). Our results contribute to the literature identifying disparities in dementia care and highlight the need for additional research on the mechanisms through which race affects dementia outcomes.

Racial differences persisted for the measure of functional ability but in the opposite direction. At the time of diagnosis, African Americans had less functional dependence than whites. It is not entirely clear why this is the case. One explanation may be that as family caregivers assess functional ability, there may be different interpretations among African Americans and whites (8). Although we controlled for informant type, due to sparse data, we were unable to determine the effect of an interaction between informant and race.

Region of residence was a significant predictor of change in the cognitive, functional, and behavioral models. Our measure of region is broad but likely captures differences in the recruiting and referral practices of providers within an ADC region.

In our study, the annual rate of change in cognition in the first year was −1.518 MMSE points. This is comparable to recently published findings from Tschanz and colleagues who used population-based data from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging to evaluate trajectories of dementia patients and reported a mean annual rate of change of −1.500 MMSE points (3). However, unlike our study, they did not account for racial differences or control for clinical factors.

MMSE changes >2 are considered clinically meaningful (19). In our study, change in cognitive function in the first year is borderline clinically significant, but over time, the cumulative effect is clearly clinically meaningful. By the third year post-diagnosis patients begin experiencing annual clinically meaningful cognitive declines.

Studies have reported conflicting results for the effect of vascular risk factors on cognitive decline (5,20,21). Our results indicate that the presence of vascular risk factors (history of hypertension and congestive heart failure) result in a slower decline. This may be indicative of differences between individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia (21,22).

Functional ability worsened by 3.464 FAQ points in the first year. Without established clinical thresholds, it is difficult to conceptualize what this change represents. One interpretation is that within the first year an average individual developed three additional functional limitations. In the immediate years post-diagnosis, individuals experienced steep functional declines, but over time, the rate of decline decreased. This finding is in contrast to the pattern observed for cognitive and behavioral trajectories. The pattern of functional decline may be explained by the fact that the FAQ predominately measures instrumental activities of daily living that are complex and result in losses of independence earlier in the disease course compared with losses in activities of daily living.

Behavior worsened by 0.354 NPI points in the first year. This represents a small change and is not likely to be clinically meaningful. The most troubling behaviors are more common in the moderate to advanced stages of the disease that is illustrated by the sharp increase in the NPI-Q score as a patient’s disease progresses (23). Cognitive status was the only clinical characteristic to predict change in behavioral symptoms over time, but a history of psychiatric problems or hypertension was associated with more behavioral symptoms at diagnosis. To our knowledge, the NPI-Q has not been used to evaluate behavioral trajectories in dementia, but conceptually our analysis differs from others by incorporating cognitive status and race as explanatory variables (3,23).

Our study has some limitations. Although it uses national data from ADCs, it is not nationally representative. Compared with a nationally representative sample, our sample is more educated and white, but the average age at the time of diagnosis is similar (11,24). Additionally, our cognitive trajectories are consistent with a study using a population-based sample lending support to the validity of our findings (3). Other limitations were that we did not account for the effect of apolipoprotein E ε4 allele. Finally, to evaluate nonlinear change, we limited our analysis to individuals with at least three observations and complete data at baseline. This may limit the generalizability of results, as patients with fewer observations may be sicker.

In conclusion, our study finds that sociodemographic characteristics and clinical comorbidities predict cognitive and functional changes over time in newly diagnosed dementia patients. Cognition status is the only factor to predict behavioral changes over time. Our results provide a means of identifying individuals at risk of faster decline and facilitate care planning by providers and caregivers for different dementia profiles.

Funding

This work was supported by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1R36HS024165-01).

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI Marie-Francoise Chesselet, MD, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), and P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

References

- 1. Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11: 332–384. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grand JH, Caspar S, MacDonald SW. Clinical features and multidisciplinary approaches to dementia care. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;4:125. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S17773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tschanz JT, Corcoran CD, et al. Progression of cognitive, functional and neuropsychiatric symptom domains in a population cohort with alzheimer’s dementia: the Cache County Dementia Progression study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:532. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181faec23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cortes F, Nourhashémi F, Guérin O, et al. Prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease today: a two-year prospective study in 686 patients from the REAL-FR Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4:22–29. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2007.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Helzner EP, Luchsinger JA, Scarmeas N, et al. Contribution of vascular risk factors to the progression in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:343–348. doi:10.1001/archneur.66.3.343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Han L, Cole M, Bellavance F, McCusker J, Primeau F. Tracking cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease using the mini-mental state examination: a meta-analysis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12:231–247. doi:10.1017/S1041610200006359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Delva F, Auriacombe S, Letenneur L, et al. Natural history of functional decline in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40:57–67. doi:10.3233/JAD-131862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chin AL, Negash S, Hamilton R. Diversity and disparity in dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25:187–195. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e318211c6c9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mayeux R, Stern Y. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006239. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:210–216. doi:10.1097/01.wad.0000213865.09806.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Plassman BL, Langa KM, McCammon RJ, et al. Incidence of dementia and cognitive impairment, not dementia in the United States. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:418–426. doi:10.1002/ana.22362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, Williams SP, Singh H. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:306–314. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181a6bebc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beach TG, Monsell SE, Phillips LE. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers, 2005–2010. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012: 71:266–273.doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e31824b211b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Slavin MJ, Brodaty H, Sachdev PS. Challenges of diagnosing dementia in the oldest old population. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:1103–1111. doi:10.1093/gerona/glt051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psych Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Chance JM, Filos S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37:323–329. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi:10.1212/WNL.44.12.2308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lines L, Sherif N, Wiener J. Racial and Ethnic Disparities Among Individuals With Alzheimer’s Disease in the United States: A Literature Review. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI Press; 2014. Publication No. RR-0024-1412. doi:10.3768/rtipress.2014.RR.0024.1412 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hensel A, Angermeyer MC, Riedel-Heller SG. Measuring cognitive change in older adults: reliable change indices for the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 2007;78:1298–1303. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2006.109074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bellew KM, Pigeon JG, Stang PE, Fleischman W, Gardner RM, Baker WW. Hypertension and the rate of cognitive decline in patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18: 208–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Groves WC, Brandt J, Steinberg M. Vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: is there a difference? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12:305–315. doi:10.1176/jnp.12.3.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gure TR, Kabeto MU, Plassman BL, Piette JD, Langa KM. Differences in functional impairment across subtypes of dementia. J Gerontol A Bio Sci Med Sci. 2010;65A:434–441. doi:10.1093/gerona/glp197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lopez OL, Becker JT, Sweet RA, et al. Psychiatric symptoms vary with the severity of dementia in probable Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15:346–353. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.15.3. 346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kokmen E, Özsarfati Y, Beard CM, O’Brien PC, Rocca WA. Impact of referral bias on clinical and epidemiological studies of Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;49:79–83. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(95) 00031-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.