Abstract

Background

With the release of the National Lung Screening Trial results, the detection of peripheral pulmonary lesions (PPLs) is likely to increase. Computed tomography (CT)-guided percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy (PTNB) and radial probe endobronchial ultrasound (r-EBUS)-guided transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) are recommended for tissue diagnosis of PPLs.

Methods

A systematic review of published literature evaluating the accuracy of r-EBUS-TBLB and CT-PTNB for the diagnosis of PPLs was performed to determine point sensitivity and specificity, and to construct a summary receiver-operating characteristic curve.

Results

This review included 31 publications dealing with EBUS-TBLB and 14 publications dealing with CT-PTNB for the diagnosis of PPLs. EBUS-TBLB had point sensitivity of 0.69 (95% CI: 0.67–0.71) for the diagnosis of peripheral lung cancer (PLC), which was lower than the sensitivity of CT-PTNB (0.94, 95% CI: 0.94–0.95). However, the complication rates observed with EBUS-TBLB were lower than those reported for CT-PTNB.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis showed that EBUS-TBLB is a safe and relatively accurate tool in the investigation of PLC. Although the yield remains lower than that of CT-PTNB, the procedural risks are lower.

Keywords: Computed tomography-guided percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy (CT-PTNB), radial probe endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial lung biopsy (r-EBUS-TBLB), peripheral pulmonary lesions, diagnosis, meta-analysis

Introduction

With the established role of low-dose helical computed tomography (CT) screening for lung cancer (1,2) and the wide application of high-resolution CT (HRCT), pulmonary lesions are increasingly detected (3). Peripheral pulmonary lesions (PPLs) are a common problem in pulmonary practice. PPLs are defined as focal radiographic opacities that may be characterized as nodules (<3 cm) or masses (>3 cm). Solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN) is defined as a single, well-circumscribed radiographic opacity ≤30 mm in diameter that is completely surrounded by aerated lung and is not associated with atelectasis, hilar enlargement, or pleural effusion (4). With HRCT, PPLs can be categorized in a more accurate and detailed way. A ground-glass opacity (GGO) is a specific morphological type of pulmonary nodule (5).

To establish a tissue diagnosis, multiple approaches including sputum cytology, bronchoscopic sampling, and CT-guided percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy (PTNB), may be undertaken. Conventional bronchoscopy has been used for several decades to diagnose PPLs (i.e., lesions that are not endobronchially visible), but its diagnostic yield is lower than 20% (6,7). The addition of imaging and guidance technology, such as radial probe endobronchial ultrasound (r-EBUS) and electromagnetic navigational bronchoscopy, has been shown by some studies to improve the diagnostic performance of transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB). Several groups have now published their experience with r-EBUS-TBLB of PPLs. While there are a number of published case series evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of this diagnostic modality, the population recruited in each study was small and, therefore, the precision of the derived estimates varied widely. The aims of our study were to perform a systematic review of r-EBUS-TBLB and to ascertain the pooled sensitivity and specificity of this modality compared with published results of CT-PTNB for the diagnosis of peripheral lung cancer (PLC).

Methods

Publication search

Electronic databases of Medline (using PubMed as the search engine), Embase, Cochrane, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure were searched to identify suitable studies. Articles were identified with the use of the related articles function in PubMed. The references of the articles identified were also searched manually. The search terms used in this meta-analysis were “endobronchial ultrasound”, “lung biopsy”, “peripheral lung cancer”, “peripheral pulmonary lesions”, “computed tomography”, “CT’’, ‘‘sensitivity and specificity’’, and ‘‘accuracy’’. An upper date limit of Aug 01, 2016 was applied; no lower date limit was used.

Inclusion criteria

We sought to identify all studies that used R-EBUS-TBLB and/or CT-PTNB for the investigation of PPLs. For inclusion, the studies must have met the following criteria: (I) evaluated the sensitivity (true-positive rate) and the specificity (false-positive rate) of r-EBUS-TBLB and/or CT-PTNB for the diagnosis of PPLs; (II) included at least 20 patients with PPLs for R-EBUS-TBLB and 200 patients with PPLs for CT-PTNB, since studies with smaller population may be vulnerable to selection bias; (III) histopathology analysis and/or close clinical follow-up for at least one year was used as the reference standard; and (IV) the search was performed without any restrictions on language and focused on studies that had been conducted in humans. Conference abstracts and letters to journal editors were excluded because of the limited data presented. Two reviewers (P Zhan and QQ Zhu) independently evaluated the study eligibility for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The studies included were assessed independently by two reviewers who were blinded to publication details; disagreements were resolved by consensus. Extracted data included the following items: participant characteristics, publication year, patient enrolment and study design, use of reference standards, methodological quality, sensitivity data, and complication rate.

We assessed the methodological quality of the studies using guidelines published by the standards for reporting diagnostic accuracy (QUADAS) tool (8), with a maximum score of 14. Appraisal of the quality of the diagnostic accuracy of the primary studies was based on empirical evidence, expert opinion, and formal consensus.

Statistical analysis

The standard methods recommended for meta-analyses of diagnostic test evaluations were used (9). Meta-analyses were performed using a statistical software program (Meta-DiSc Version 1.4; XI Cochrane Colloquium; Barcelona, Spain). We computed the following measures of test accuracy for each study: sensitivity; specificity; positive likelihood ratio (PLR); negative likelihood ratio (NLR); and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR).

The analysis was based on a summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve (9,10). The sensitivity and specificity for the single test threshold identified for each study were used to plot an SROC curve (11). A random effects model was used to calculate the average sensitivity, specificity, and other measures across studies (12,13). The term heterogeneity, when used in relation to meta-analyses, referred to the degree of variability in results across studies. We used the χ2 and Fisher exact tests to detect statistically significant heterogeneity, as appropriate. The relative DOR (RDOR) was calculated according to standard methods to analyze the change in diagnostic precision in a study per unit increase in the covariate (14,15).

Results

Study characteristics

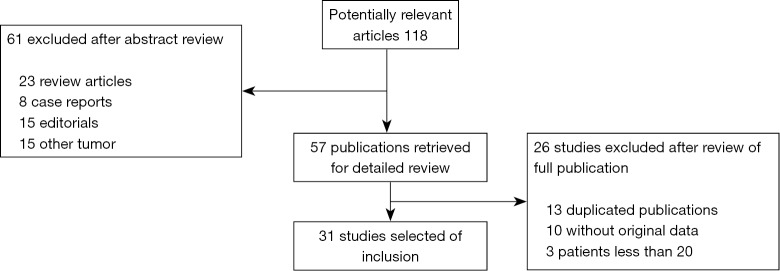

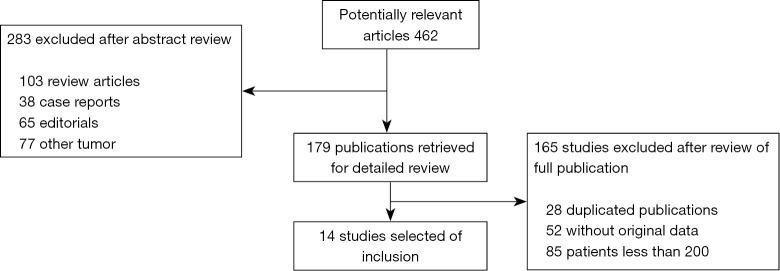

After independent review, 31 publications (16-39) and (40-46) on r-EBUS-TBLB and 15 publications (47-61) on CT-PTNB for the diagnosis of PPLs were considered to be eligible for inclusion in the analysis. The study search process is shown in Figures 1 and 2. The QUADAS scores of these studies are outlined in Table 1. Tables 2 and 3 present the principal characteristics of these studies. Among the 14 CT-PTNB publications, 12 were published in English and 2 were in Chinese. Among the 31 published studies on r-EBUS-TBLB, 29 were in English and 2 were in Chinese.

Figure 1.

Identification, inclusion, and exclusion of studies on r-EBUS-TBLB. r-EBUS, radial probe endobronchial ultrasound; TBLB, transbronchial lung biopsy.

Figure 2.

Identification, inclusion, and exclusion of studies on CT-PTNB. CT, computed tomography; PTNB, percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy.

Table 1. Main characteristics of selected studies on r-EBUS-TBLB.

| Author-year | No. of patients | Study design | Reference/comparison test | Q score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herth-2002 | 50 | Prospective randomized cross-over study: EBUS versus fluoroscopy | Surgical resection | 8 |

| Yang-2004 | 122 | Retrospective audit | Histology by alternate means or clinical surveillance | 3 |

| Shirakawa-2004 | 50 | Prospective case series versus retrospective controls | Histology by alternate means | 3 |

| Kurimoto-2004 | 150 | Prospective case series | Histology by alternate means | 3 |

| Paone-2005 | 87 | Prospective, randomized, blinded study | Histology by alternate means | 3 |

| Asahina-2005 | 30 | Unclear | Histology by alternate means | 3 |

| Herth-2006 | 54 | Prospective case series | Surgical resection | 4 |

| Eberhardt-2007 | 39 | Prospective RCT | Surgical resection | 3 |

| Yoshikawa-2007 | 121 | Prospective case series | Histology by alternate means | 3 |

| Yamada-2007 | 155 | Retrospective | NA | 2 |

| Asano-2008 | 31 | Prospective case series | Surgical resection | 3 |

| Huang-2009 | 83 | Retrospective audit | Histology by alternate means or surveillance | 4 |

| Eberhardt-2009 | 100 | Prospective case series | Histology by alternate means | 4 |

| Oki-2009 | 86 | Prospective study | Histology by alternate means or clinical surveillance | 4 |

| Chao-2009 | 88 | Prospective, randomized trial. | NA | 8 |

| Disayabutr-2010 | 152 | Prospective cross-sectional study | Histology by alternate means or clinical surveillance | 6 |

| Mizugaki-2010 | 107 | Retrospective | Histology by alternate means or clinical surveillance | 3 |

| Steinfort-2011 | 51 | Prospective randomized | Histology by alternate means or clinical surveillance | 8 |

| Fielding-2012 | 64 | Prospective, randomized trial, EBUS-GS or CT-guided | Histology by alternate means or clinical surveillance | 8 |

| Hsia-2012 | 40 | Retrospective | NA | 2 |

| Lin-2012 | 39 | Retrospective | Surgical resection | 3 |

| Ishida-2012 | 65 | Retrospective | NA | 2 |

| Oki-2012 | 203 | Prospective EBUS-TBB under 3.4-mm or 4.0-mm thin bronchoscope with GS | Histology by alternate means or clinical surveillance | 8 |

| Fuso-2013 | 662 | Retrospective | Histology by alternate means or clinical surveillance | 3 |

| Li-2014 | 75 | Retrospective | Histology by alternate means | 4 |

| Chavez-2014 | 212 | Retrospective | Histology by alternate means | 4 |

| Zhang-2015 | 117 | Retrospective | Histology by alternate means | 4 |

| Durakovic-2015 | 147 | Retrospective | Histology by alternate means or clinical surveillance | 4 |

| Tang-2016 | 105 | Retrospective | Histology by alternate means or clinical surveillance | 4 |

| Fukusumi-2016 | 27 | Retrospective | Histology by alternate means | 4 |

| Hayama-2016 | 27 | Retrospective | Histology by alternate means or clinical surveillance | 4 |

r-EBUS, radial probe endobronchial ultrasound; TBLB, transbronchial lung biopsy; Q, QUAD; NA, not applicable; CT, computed tomography.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies on r-EBUS-TBLB.

| Study-year | No. of patients with LC | TP | FN | Complication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe bleeding | Pneumothorax with tube | ||||

| Herth-2002 | 45 | 36 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| Yang-2004 | 122 | 80 | 42 | NA | NA |

| Shirakawa-2004 | 24 | 17 | 7 | NA | NA |

| Kurimoto-2004 | 101 | 82 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| Paone-2005 | 87 | 60 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| Asahina-2005 | 23 | 17 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Herth-2006 | 39 | 28 | 11 | 0 | 1 |

| Eberhardt-2007 | 32 | 23 | 9 | 0 | 2 |

| Yoshikawa-2007 | 103 | 65 | 38 | 0 | 0 |

| Yamada-2007 | 128 | 90 | 38 | NA | NA |

| Asano-2008 | 27 | 23 | 4 | NA | NA |

| Huang-2009 | 65 | 39 | 26 | 0 | 0 |

| Eberhardt-2009 | 87 | 41 | 16 | 0 | 2 |

| Oki-2009 | 44 | 35 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Chao-2009 | 72 | 57 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Disayabutr-2010 | 99 | 58 | 41 | 0 | 0 |

| Mizugaki-2010 | 91 | 66 | 25 | NA | NA |

| Steinfort-2011 | 32 | 25 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Oki-2012 | 82 | 58 | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| Fielding-2012 | 23 | 17 | 6 | 0 | 2 |

| Hsia-2012 | 17 | 12 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Lin-2012 | 39 | 30 | 9 | NA | NA |

| Ishida-2012 | 50 | 38 | 12 | 0 | 1 |

| Fuso-2013 | 359 | 255 | 104 | NA | NA |

| Li-2014 | 32 | 27 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Chavez-2014 | 212 | 143 | 69 | 0 | 0 |

| Zhang-2015 | 88 | 66 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Durakovic-2015 | 147 | 39 | 108 | 0 | 2 |

| Tang-2016 | 14 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Fukusumi-2016 | 18 | 12 | 6 | NA | NA |

| Hayama-2016 | 27 | 20 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Total complication (%) | 0.087 | 0.48 | |||

r-EBUS, radial probe endobronchial ultrasound; TBLB, transbronchial lung biopsy; LC, lung cancer; TP, true-positive; FN, false-negative; NA, not applicable.

Table 3. Characteristics of included studies on CT-PTNB.

| Study-year | No. of patients with LC | Source | TP | FN | Complication (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe bleeding | Pneumothorax with tube | |||||

| Yang-2015 | 217 | China | 215 | 2 | 11 | 3 |

| Brandén-2014 | 463 | Sweden | NA | NA | NA | 27 patients (6%) |

| Lee-2014 | 766 | South Korea | 733 | 33 | 1 patient | 13 patients |

| Wang-2013 | 623 | China | 618 | 5 | 0 | 8 patients (1.3%) |

| Wang-2014 | 342 | China | 333 | 9 | 0 | 5 patients (1.5%) |

| Choi-2013 | 290 | South Korea | 270 | 20 | NA | NA |

| Loh-2013 | 399 | Singapore | 381 | 18 | 1 patient | 12 patients (4.3%) |

| Yuan-2011 | 1014 | China | 962 | 52 | 1 patient | 15 patients (1.5%) |

| Wei-2011 | 329 | China | 305 | 24 | NA | NA |

| Laspas-2008 | 409 | Greece | 384 | 25 | 0 | 1 patient |

| D’Alessandro-2007 | 583 | Italy | 542 | 41 | 0 | 29 patients (18%) |

| Priola-2007 | 612 | Italy | 552 | 60 | NA | NA |

| Tomiyama-2006 | 6881 | Japan | NA | NA | 22 | 14 |

| Yeow-2003 | 631 | China | 587 | 44 | NA | NA |

| Casamassima-1988 | 419 | Italy | 367 | 52 | NA | NA |

| Total complication (%) | 0.32 | 1.09 | ||||

CT, computed tomography; PTNB, percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy; LC, lung cancer; TP, true-positive; FN, false-negative; NA, not applicable.

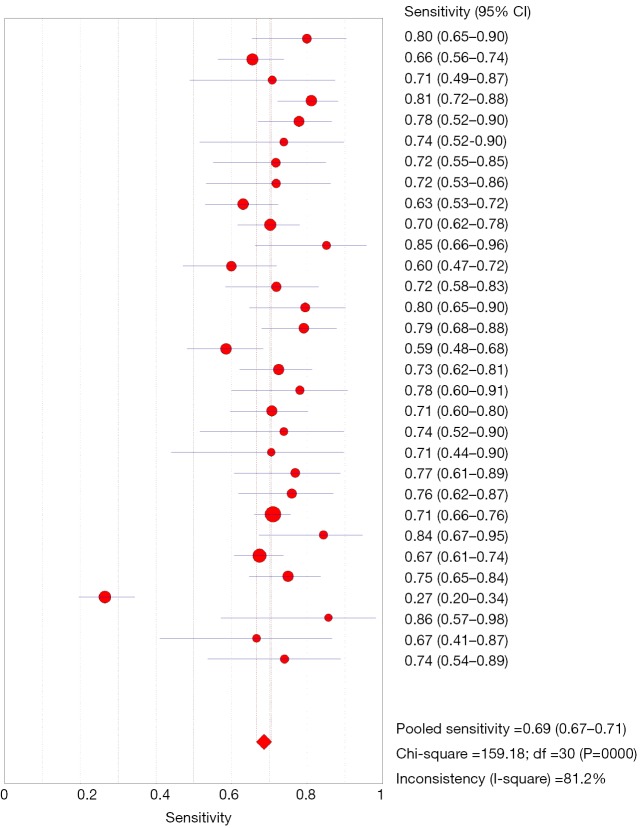

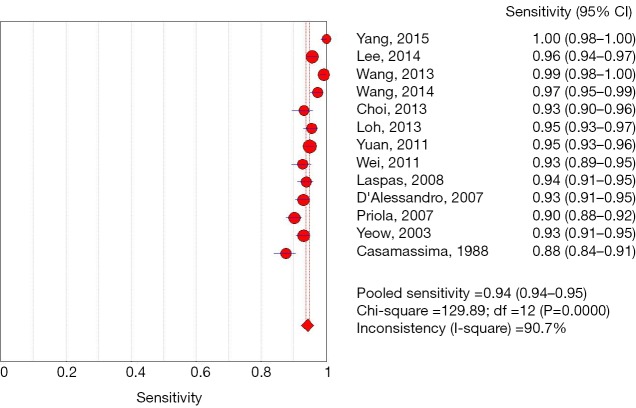

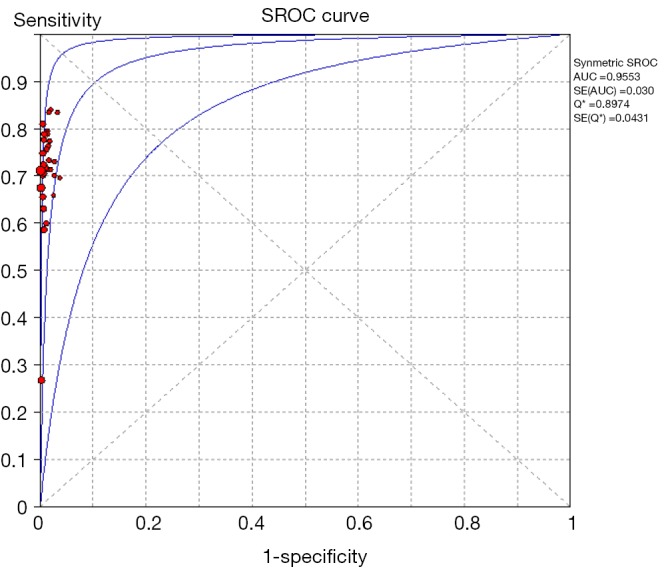

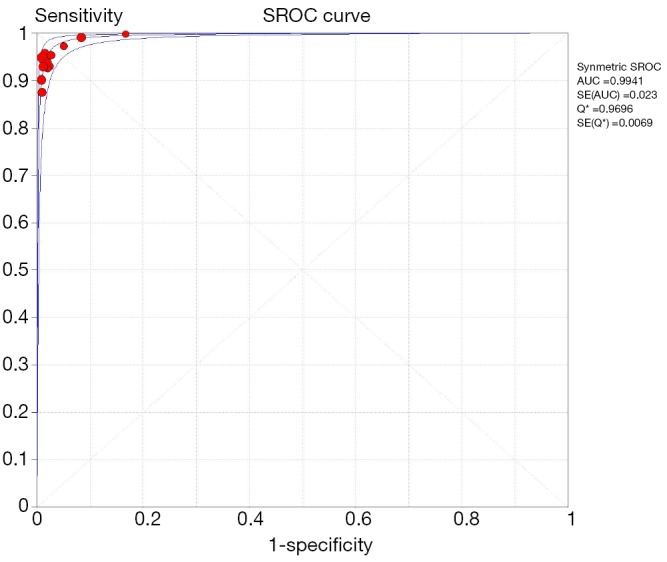

Diagnostic accuracy

Among 31 studies that evaluated the sensitivity of r-EBUS-TBLB for the diagnosis of PPLs, point sensitivity for pooled data was 0.69 (95% CI: 0.67–0.71) (Figure 3) and the area under the SROC curve was 0.955 (SE =0.03) (Figure 4). Among 13 studies that evaluated the sensitivity of CT-PTNB for the diagnosis of PPLs, the point sensitivity for pooled data was 0.94 (95% CI: 0.94–0.95) (Figure 5) and the area under the SROC curve was 0.994 (SE =0.0023) (Figure 6).

Figure 3.

Forest plot: sensitivity analysis for of r-EBUS-TBLB for the diagnosis of PPLs. r-EBUS, radial probe endobronchial ultrasound; TBLB, transbronchial lung biopsy; PPL, peripheral pulmonary lesion.

Figure 4.

Summary receiver operating characteristics plot: r-EBUS-TBLB for the diagnosis of PPLs. r-EBUS, radial probe endobronchial ultrasound; TBLB, transbronchial lung biopsy; PPL, peripheral pulmonary lesion.

Figure 5.

Forest plot: sensitivity analysis for of CT-PTNB for the diagnosis of PPLs. CT, computed tomography; PTNB, percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy; PPL, peripheral pulmonary lesion.

Figure 6.

Summary receiver operating characteristics plot: CT-PTNB for the diagnosis of PPLs. CT, computed tomography; PTNB, percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy; PPL, peripheral pulmonary lesion.

Complication rates

The main limitation of CT-PTNB for the diagnosis of PPLs was the rate of complications, including pneumothorax and bleeding. The pooled rate across all included studies was 0.32% (36 out of 11,234) for severe bleeding and 1.09% (127 out of 11,697) for pneumothorax that needed chest tube drainage. On the other hand, the complication rates observed with r-EBUS-TBLB were low. The pooled rate across all included studies was 0.087% (2 out of 2,284) for severe bleeding and 0.48% (11 out of 2,284) for pneumothorax that needed chest tube drainage.

Discussion

The present meta-analysis showed that r-EBUS-TBLB had a point sensitivity of 0.69 (95% CI: 0.67–0.71) for the diagnosis of PLC, which was lower than the sensitivity of CT-PTNB (0.94, 95% CI: 0.94–0.95). Although the diagnostic yield was not superior to that of CT-PTNB, the major advantage of r-EBUS-TBLB over CT-PTNB was its safety profile. Our meta-analysis demonstrated overall rates of only 0.087% for severe bleeding and 0.48% for pneumothorax that needed chest tube drainage. In comparison, many studies describing CT-PTNB reported 0.32% rate of severe bleeding and 1.09% overall rate for pneumothorax requiring chest tube drainage.

Since Haaga and Alfidi reported the first case of CT-PTNB in 1976 (62), the procedure had been constantly developed and is currently widely employed as a routine diagnostic technique for PPLs, owing to its simplicity and minimal invasiveness. Recently, we performed a retrospective study (47) to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of CT-PTNB for SPN. Out of the 311 patients with SPN, 2 were false-positive cases, 12 were false-negative cases, and 8 were undiagnosed, resulting in a 92.9% diagnostic accuracy of CT-PTNB. However, PTNB has been known to have major complications of pneumothorax and pulmonary hemorrhage, with reported incidence rates of 10–40% and 26–33%, respectively (63). In our previous study (47), there were 55 cases of pneumothorax (17.7%), 2 cases needed thoracentesis and 1 case needed chest tube drainage. In addition, the diagnostic yield was influenced by size of the lesion, size of the needle, number of passes, and use of rapid on-site evaluation (64,65).

On the other hand, conventional bronchoscopy for PPLs can be performed using several instruments and sampling methods, including transbronchial biopsy forceps, transbronchial brush, transbronchial needle aspiration, and bronchoalveolar lavage. However, the sensitivity of traditional bronchoscopic biopsy was only 14–34% for nodules <2 cm (66). The sensitivity increased to 63% when nodules were >2 cm in size, but decreased as the distance from the hilum increased. Recently, image guidance has been used during bronchoscopy. One of which is r-EBUS that uses a 20-MHz ultrasound probe that can be passed through the working channel of a bronchoscope into the lung periphery. The r-EBUS probe can be passed within a disposable guide sheath or by itself. Two previous meta-analyses have evaluated the performance of r-EBUS for the investigation of PPLs. The one by Steinfort et al. (67) on 16 studies of 1,420 patients that underwent r-EBUS for diagnosis of PPLs showed a pooled sensitivity of 73% (95% CI: 70–76%). Another meta-analysis (68) reported pooled diagnostic yields of 73.2% (95% CI: 64.4–81.9%) for r-EBUS with a guide sheath and 71.1% (95% CI: 66.5–75.7%) for r-EBUS without a guide sheath.

It has been reported that several guided-bronchoscopy technologies could improve the yield of transbronchial biopsy for PPLs diagnosis, such as electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy (ENB), virtual bronchoscopy (VB), r-EBUS, ultrathin bronchoscope, and guide sheath. Wang Memoli et al. study (68) performed the meta-analysis to determine the overall diagnostic yield of guided bronchoscopy using one or a combination of these technologies. They found that the pooled diagnostic yield was 70%, which is higher than the yield for traditional transbronchial biopsy. The yield increased as the lesion size increased. Only a few studies have focused on impact of the “bronchus sign”, defined as a bronchus leading directly into the lesion on transverse CT imaging, although we have recognised the importance of the “bronchus sign” for the diagnosis of PPLs within our own practice.

The major limitation of our findings was the quality of studies included in the meta-analysis. The consistency of the patient populations in the individual studies was unclear because the selection criteria were not clear in the majority of studies. Therefore, it is difficult to know whether the spectrum of study subjects was representative of patients who would undergo r-EBUS-TBLB in clinical practice. In addition, some factors influencing the performance of r-EBUS-TBLB were not described in most papers included in our meta-analysis. These factors include bronchoscopist experience, number of biopsies taken, proximity of the PPL to central airways, and radiologic appearance of PPLs.

In summary, our meta-analysis confirmed that the overall diagnostic performance of r-EBUS-TBLB for PPLs was relatively accurate, although lower than that of CT-PTNB. However, our results indicate a favorable safety profile of EBUS-TBLB, supporting EBUS-TBLB as a viable investigation in patients with PPLs. This data once more suggests that radial EBUS may be the initial test of choice for the diagnosis of PPLs in those patients deemed at higher risk of a pneumothorax from CT-PTNB such as in the context of severe emphysema. The diagnostic sensitivity of r-EBUS-TBLB may be influenced by the prevalence of malignancy in the patient cohort being examined. Further randomized-controlled trials are required to evaluate the generalizability of our results to more clearly defined patient populations.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20140736), Clinical Science and Technology Project of Jiangsu Province (No. BL2013026), The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81302032, 81401903, 81572937, 81572273), and Program of Nanjing Science and Technology of Nanjing Science and Technology Committee (No. 201605059).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Marshall HM, Bowman RV, Yang IA, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography: a review of current status. J Thorac Dis 2013;5 Suppl 5:S524-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McWilliams A, Tammemagi MC, Mayo JR, et al. Probability of cancer in pulmonary nodules detected on first screening CT. N Engl J Med 2013;369:910-9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1214726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel VK, Naik SK, Naidich DP, et al. A practical algorithmic approach to the diagnosis and management of solitary pulmonary nodules: part 1: radiologic characteristics and imaging modalities. Chest 2013;143:825-39. 10.1378/chest.12-0960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ost D, Fein AM, Feinsilver SH. Clinical practice. The solitary pulmonary nodule. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2535-42. 10.1056/NEJMcp012290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhan P, Xie H, Xu C, et al. Management strategy of solitary pulmonary nodules. J Thorac Dis 2013;5:824-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallace JM, Deutsch AL. Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy and percutaneous needle lung aspiration for evaluating the solitary pulmonary nodule. Chest 1982;81:665-71. 10.1378/chest.81.6.665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roth K, Hardie JA, Andreassen AH, et al. Predictors of diagnostic yield in bronchoscopy: a retrospective cohort study comparing different combinations of sampling techniques. BMC Pulm Med 2008;8:2. 10.1186/1471-2466-8-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, et al. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:25. 10.1186/1471-2288-3-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devillé WL, Buntinx F, Bouter LM, et al. Conducting systematic reviews of diagnostic studies: didactic guidelines. BMC Med Res Methodol 2002;2:9. 10.1186/1471-2288-2-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moses LE, Shapiro D, Littenberg B. Combining independent studies of a diagnostic test into a summary ROC curve: data-analytic approaches and some additional considerations. Stat Med 1993;12:1293-316. 10.1002/sim.4780121403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang J, Shi HZ, Liang QL, et al. Diagnostic value of interferon-gamma in tuberculous pleurisy: a metaanalysis. Chest 2007;131:1133-41. 10.1378/chest.06-2273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irwig L, Macaskill P, Glasziou P, et al. Meta-analytic methods for diagnostic test accuracy. J Clin Epidemiol 1995;48:119-30; discussion 131-2. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00099-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vamvakas EC. Meta-analyses of studies of the diagnostic accuracy of laboratory tests: a review of the concepts and methods. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1998;122:675-86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki S, Moro-oka T, Choudhry NK. The conditional relative odds ratio provided less biased results for comparing diagnostic test accuracy in meta-analyses. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:461-9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westwood ME, Whiting PF, Kleijnen J. How does study quality affect the results of a diagnostic meta-analysis? BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:20. 10.1186/1471-2288-5-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herth FJ, Ernst A, Becker HD. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial lung biopsy in solitary pulmonary nodules and peripheral lesions. Eur Respir J 2002;20:972-4. 10.1183/09031936.02.00032001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shirakawa T, Imamura F, Hamamoto J, et al. Usefulness of endobronchial ultrasonography for transbronchial lung biopsies of peripheral lung lesions. Respiration 2004;71:260-8. 10.1159/000077424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang MC, Liu WT, Wang CH, et al. Diagnostic value of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial lung biopsy in peripheral lung cancers. J Formos Med Assoc 2004;103:124-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurimoto N, Miyazawa T, Okimasa S, et al. Endobronchial ultrasonography using a guide sheath increases the ability to diagnose peripheral pulmonary lesions endoscopically. Chest 2004;126:959-65. 10.1378/chest.126.3.959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paone G, Nicastri E, Lucantoni G, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-driven biopsy in the diagnosis of peripheral lung lesions. Chest 2005;128:3551-7. 10.1378/chest.128.5.3551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asahina H, Yamazaki K, Onodera Y, et al. Transbronchial biopsy using endobronchial ultrasonography with a guide sheath and virtual bronchoscopic navigation. Chest 2005;128:1761-5. 10.1378/chest.128.3.1761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herth FJ, Eberhardt R, Becker HD, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial lung biopsy in fluoroscopically invisible solitary pulmonary nodules: a prospective trial. Chest 2006;129:147-50. 10.1378/chest.129.1.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eberhardt R, Anantham D, Ernst A, et al. Multimodality bronchoscopic diagnosis of peripheral lung lesions: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:36-41. 10.1164/rccm.200612-1866OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshikawa M, Sukoh N, Yamazaki K, et al. Diagnostic value of endobronchial ultrasonography with a guide sheath for peripheral pulmonary lesions without X-ray fluoroscopy. Chest 2007;131:1788-93. 10.1378/chest.06-2506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada N, Yamazaki K, Kurimoto N, et al. Factors related to diagnostic yield of transbronchial biopsy using endobronchial ultrasonography with a guide sheath in small peripheral pulmonary lesions. Chest 2007;132:603-8. 10.1378/chest.07-0637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asano F, Matsuno Y, Tsuzuku A, et al. Diagnosis of peripheral pulmonary lesions using a bronchoscope insertion guidance system combined with endobronchial ultrasonography with a guide sheath. Lung Cancer 2008;60:366-73. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang CT, Ho CC, Tsai YJ, et al. Factors influencing visibility and diagnostic yield of transbronchial biopsy using endobronchial ultrasound in peripheral pulmonary lesions. Respirology 2009;14:859-64. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01585.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eberhardt R, Ernst A, Herth FJ. Ultrasound-guided transbronchial biopsy of solitary pulmonary nodules less than 20 mm. Eur Respir J 2009;34:1284-7. 10.1183/09031936.00166708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oki M, Saka H, Kitagawa C, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial biopsy using novel thin bronchoscope for diagnosis of peripheral pulmonary lesions. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:1274-7. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181b623e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chao TY, Chien MT, Lie CH, et al. Endobronchial ultrasonography-guided transbronchial needle aspiration increases the diagnostic yield of peripheral pulmonary lesions: a randomized trial. Chest 2009;136:229-36. 10.1378/chest.08-0577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Disayabutr S, Tscheikuna J, Nana A. The endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial lung biopsy in peripheral pulmonary lesions. J Med Assoc Thai 2010;93 Suppl 1:S94-101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mizugaki H, Shinagawa N, Kanegae K, et al. Combining transbronchial biopsy using endobronchial ultrasonography with a guide sheath and positron emission tomography for the diagnosis of small peripheral pulmonary lesions. Lung Cancer 2010;68:211-5. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinfort DP, Vincent J, Heinze S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of radial probe endobronchial ultrasound versus CT-guided needle biopsy for evaluation of peripheral pulmonary lesions: a randomized pragmatic trial. Respir Med 2011;105:1704-11. 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oki M, Saka H, Kitagawa C, et al. Randomized study of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial biopsy: thin bronchoscopic method versus guide sheath method. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:535-41. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182417e60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fielding DI, Chia C, Nguyen P, et al. Prospective randomised trial of endobronchial ultrasound-guide sheath versus computed tomography-guided percutaneous core biopsies for peripheral lung lesions. Intern Med J 2012;42:894-900. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02707.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hsia DW, Jensen KW, Curran-Everett D, et al. Diagnosis of lung nodules with peripheral/radial endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial biopsy. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2012;19:5-11. 10.1097/LBR.0b013e31823fcf11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin CY, Lan CC, Wu YK, et al. Factors that affect the diagnostic yield of endobronchial ultrasonography-assisted transbronchial lung biopsy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2012;22:319-23. 10.1089/lap.2012.0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishida M, Suzuki M, Furumoto A, et al. Transbronchial biopsy using endobronchial ultrasonography with a guide sheath increased the diagnostic yield of peripheral pulmonary lesions. Intern Med 2012;51:455-60. 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.6358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuso L, Varone F, Magnini D, et al. Role of ultrasound-guided transbronchial biopsy in the diagnosis of peripheral pulmonary lesions. Lung Cancer 2013;81:60-4. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li M, Peng A, Zhang G, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound transbronchial lung biopsy with guide-sheath for the diagnosis of peripheral pulmonary lesions. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2014;37:36-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chavez C, Sasada S, Izumo T, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound with a guide sheath for small malignant pulmonary nodules: a retrospective comparison between central and peripheral locations. J Thorac Dis 2015;7:596-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang S, Zhou J, Zhang Q, et al. Endobronchial ultrasonography with distance by thin bronchoscopy in diagnosing peripheral pulmonary lesions. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2015;38:566-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Durakovic A, Andersen H, Christiansen A, et al. Retrospective analysis of radial EBUS outcome for the diagnosis of peripheral pulmonary lesion: sensitivity and complications. Eur Clin Respir J 2015;2:28947. 10.3402/ecrj.v2.28947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang C, Luo W, Zhong C, et al. The diagnostic utility of virtual bronchoscopic navigation combined with endobronchial ultrasound guided transbronchial lung biopsy for peripheral pulmonary lesions. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2016;39:38-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fukusumi M, Ichinose Y, Arimoto Y, et al. Bronchoscopy for Pulmonary Peripheral Lesions With Virtual Fluoroscopic Preprocedural Planning Combined With EBUS-GS: A Pilot Study. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2016;23:92-7. 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayama M, Okamoto N, Suzuki H, et al. Radial endobronchial ultrasound with a guide sheath for diagnosis of peripheral cavitary lung lesions: a retrospective study. BMC Pulm Med 2016;16:76. 10.1186/s12890-016-0244-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang W, Sun W, Li Q, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of CT-Guided Transthoracic Needle Biopsy for Solitary Pulmonary Nodules. PLoS One 2015;10:e0131373. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brandén E, Wallgren S, Högberg H, et al. Computer tomography-guided core biopsies in a county hospital in Sweden: Complication rate and diagnostic yield. Ann Thorac Med 2014;9:149-53. 10.4103/1817-1737.134069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee SM, Park CM, Lee KH, et al. C-arm cone-beam CT-guided percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy of lung nodules: clinical experience in 1108 patients. Radiology 2014;271:291-300. 10.1148/radiol.13131265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang B, Wu A, Fan Y, et al. Diagnostic value of computed tomography-guided percutaneous lung biopsy for malignant lung tumors. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2013;93:3023-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, Li W, He X, et al. Computed tomography-guided core needle biopsy of lung lesions: Diagnostic yield and correlation between factors and complications. Oncol Lett 2014;7:288-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choi SH, Chae EJ, Kim JE, et al. Percutaneous CT-guided aspiration and core biopsy of pulmonary nodules smaller than 1 cm: analysis of outcomes of 305 procedures from a tertiary referral center. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;201:964-70. 10.2214/AJR.12.10156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loh SE, Wu DD, Venkatesh SK, et al. CT-guided thoracic biopsy: evaluating diagnostic yield and complications. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2013;42:285-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuan DM, Lü YL, Yao YW, et al. Diagnostic efficiency and complication rate of CT-guided lung biopsy: a single center experience of the procedures conducted over a 10-year period. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011;124:3227-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wei YH, Liao MY, Xu LY. Diagnostic value of CT-guided extrapleural locating transthoracic automated cutting needle biopsy of lung lesions. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 2011;33:473-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laspas F, Roussakis A, Efthimiadou R, et al. Percutaneous CT-guided fine-needle aspiration of pulmonary lesions: Results and complications in 409 patients. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2008;52:458-62. 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2008.01990.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.D'Alessandro V, Parracino T, Stranieri A, et al. Computed-tomographic-guided biopsy of thoracic nodules: a revision of 583 lesions. Clin Ter 2007;158:509-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Priola AM, Priola SM, Cataldi A, et al. Accuracy of CT-guided transthoracic needle biopsy of lung lesions: factors affecting diagnostic yield. Radiol Med 2007;112:1142-59. 10.1007/s11547-007-0212-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tomiyama N, Yasuhara Y, Nakajima Y, et al. CT-guided needle biopsy of lung lesions: a survey of severe complication based on 9783 biopsies in Japan. Eur J Radiol 2006;59:60-4. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yeow KM, Tsay PK, Cheung YC, et al. Factors affecting diagnostic accuracy of CT-guided coaxial cutting needle lung biopsy: retrospective analysis of 631 procedures. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2003;14:581-8. 10.1097/01.RVI.0000071087.76348.C7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Casamassima F, Di Lollo S, Arganini L, et al. CT-guided percutaneous fine-needle biopsy in the histological characterization of mediastinal-pulmonary lesions. Radiol Med 1988;76:438-42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haaga JR, Alfidi RJ. Precise biopsy localization by computer tomography. Radiology 1976;118:603-7. 10.1148/118.3.603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yeow KM, See LC, Lui KW, et al. Risk factors for pneumothorax and bleeding after CT-guided percutaneous coaxial cutting needle biopsy of lung lesions. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2001;12:1305-12. 10.1016/S1051-0443(07)61556-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Covey AM, Gandhi R, Brody LA, et al. Factors associated with pneumothorax and pneumothorax requiring treatment after percutaneous lung biopsy in 443 consecutive patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2004;15:479-83. 10.1097/01.RVI.0000124951.24134.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heyer CM, Reichelt S, Peters SA, et al. Computed tomography-navigated transthoracic core biopsy of pulmonary lesions: which factors affect diagnostic yield and complication rates? Acad Radiol 2008;15:1017-26. 10.1016/j.acra.2008.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rivera MP, Mehta AC; American College of Chest Physicians. Initial diagnosis of lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest 2007;132:131S-148S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Steinfort DP, Khor YH, Manser RL, et al. Radial probe endobronchial ultrasound for the diagnosis of peripheral lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2011;37:902-10. 10.1183/09031936.00075310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang Memoli JS, Nietert PJ, et al. Meta-analysis of guided bronchoscopy for the evaluation of the pulmonary nodule. Chest 2012;142:385-93. 10.1378/chest.11-1764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]