Abstract

Plants require several essential mineral nutrients for their growth and development. These nutrients are required to maintain physiological processes and structural integrity in plants. The root architecture has evolved to absorb nutrients from soil and transport them to other parts of the plant. Nutrient deficiency affects several physiological and biological processes in plants and leads to reduction in crop productivity and yield. To compensate this adversity, plants have developed adaptive mechanisms to enhance the acquisition, conservation, and mobilization of these nutrients under deficient or adverse conditions. In addition, plants have evolved an intricate nexus of complex signaling cascades, which help in nutrient sensing and uptake as well as to maintain nutrient homeostasis. In recent years, small non-coding RNAs such as micro RNAs (miRNAs) and endogenous small interfering RNAs have emerged as important component in regulating plant stress responses. A set of these small RNAs (sRNAs) have been implicated in regulating various processes involved in nutrient uptake, assimilation, and deficiency. In response to phosphorus (P) and sulphur (S) deficiencies, role of sRNAs, miR395 and miR399, have been identified to be instrumental; however, many more miRNAs might be involved in regulating the plant response to these nutrient stresses. These sRNAs modulate expression of target genes in response to P and S deficiencies and regulate their uptake and utilization for proper growth and development of the plant. This review summarizes the current understanding of uptake, sensing, and signaling of P and S and highlights the regulatory role of sRNAs in adaptive responses to these nutrient stresses in plants.

Keywords: abiotic stress, gene regulation, miRNA, nutrient deficiency, nutrient homeostasis

Introduction

Plants acquire mineral nutrients from the soil through extensive root system for their growth and development (Lynch, 2011; Gruber et al., 2013). Conventionally, there are 16 essential mineral nutrients, which are crucial for plant development. These are required in different amounts and thus are categorized as primary, secondary, and micronutrients. Primary or the macronutrients include nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K); essentially required in various processes including photosynthesis, cell division, protein synthesis, and disease resistance. Secondary nutrients comprising calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and sulfur (S) are required in lesser amount than the primary nutrients by the plants. Similarly, micronutrients required in trace amounts comprise boron (Bo), chlorine (Cl), iron (Fe), manganese (Mg), molybdenum (Mo), and zinc (Zn; Schachtman and Shin, 2007). The requirement of micronutrients is as essential as the primary and secondary nutrients for plant growth and development. These nutrients are taken up by the root system from the soil and associated microorganisms such as rhizobium and mycorrhizal associations. Most of the absorption of nutrients from soil is performed by the root hairs that form the extreme most component of the root system. Roots being the first site to sense nutrient availability maximizes nutrient uptake using high surface area and volume ratio (Gruber et al., 2013). Thus, the plants restructure the root architecture according to the nutrient availability, e.g., the succulents have deep penetrating with developed primary root whereas the aquatic plants have sparsely distributed and less developed primary roots. Plants possess counteracting mechanisms against nutrient deficiency that includes sensing, signaling, and acquisition of nutrients and restructuring the root architecture depending upon nutrient availability in the soil. The restructuring happens in the nutrient pockets of the soils where the root hairs and secondary roots develop well to enhance nutrient absorption whereas the number and length of root hairs and other root system components decreases in the nutrient deficient regions of the soil. From the rhizosphere and root epidermal cells, nutrients are transported to the vascular cells and are further allocated to different tissues (Nath and Tuteja, 2016). Different transporters including ion channels, electrochemical potential-driven transporters, group translocators, electron carriers, and voltage gated channels present on the plasma membrane take part in the nutrient uptake and allocation in various cellular organelles and tissues (Ludewig and Frommer, 2002; Saier et al., 2016; Sasaki et al., 2016). Under nutrient deficiency, a complex signaling cascade from aerial plant tissue activates various biochemical components required for uptake and transport of nutrients to meet optimum requirement for growth and development.

In recent past, role of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have been implicated in stress response including nutrient deficiency (Sunkar et al., 2007; Mao et al., 2009; Kuo and Chiou, 2011; Sharma et al., 2015). MicroRNAs (miRNAs) and endogenous small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) of 21–24 nucleotides length are two major classes of small regulatory RNAs in plants. Though these small RNAs (sRNAs) differ in their mode of biogenesis, regulate several processes through transcriptional (TGS) and post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS; Napoli et al., 1990; Vaucheret and Fagard, 2001; Valencia-Sanchez et al., 2006; Khraiwesh et al., 2012; Tiwari et al., 2014). A number of studies suggest that these sRNAs regulate gene expression and thus modulate plant growth and development in normal or stress conditions including nutrient deficiency (He and Hannon, 2004; Sunkar et al., 2007; Paul et al., 2015; Melnikova et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016). Plants adapt to nutrient deficient conditions by modulating the expression of genes encoding specific group of transporters and metabolic enzymes. This differential regulation of these genes is controlled by a set of miRNA families. Major research endeavors have identified several miRNAs responsive to nutrient deficiencies in different plant species including Arabidopsis, maize, rice, and Medicago truncatula (Sunkar et al., 2007). In Arabidopsis, miR156 family has been identified to be most responsive toward nitrogen deficiency (Liang et al., 2012). In addition, involvement of miR160 and miR170 has been shown in altering root structure architecture of plants in response to nitrogen deficiency (Liang et al., 2012). Nodule development under nitrogen deficiency has been shown to be regulated by miR169 and miR172 reported in (Combier et al., 2006; Yan et al., 2013). These miRNAs up regulate nitrate transporters under nitrogen deficiency conditions. Recent studies using genome-wide expression analysis and functional genomics approaches have identified differentially expressed miRNAs and their regulatory roles in different nutrient as well as other metal stresses including Copper (Cu), Iron (Fe), Manganese (Mn), and, Zinc (Zn). miRNAs including miR397, miR408, and miR857, have been observed to be up-regulated during Cu starvation and functions in the regulation of Cu levels in plants (Abdel-Ghany and Pilon, 2008). Under Fe-deficiency in plants, eight conserved miRNA genes of five families including miR854, were observed to be up-regulated. Analysis of cis-regulatory elements upstream of these miRNA genes revealed presence of IDE1/IDE2 (Iron-deficiency responsive cis-Elements 1 and 2) motifs in their promoter regions (Kong and Yang, 2010). Notably, the induction of miRNAs modulate expression of array of genes and thus facilitate nutrient homeostasis in plants. In this review, recent progress and updates related to sRNAs-mediated mineral nutrient uptake, sensing and signaling have been reviewed. The focus of the review is on the nutrients P and S, which are essential for the growth and stress response in plants.

Phosphorus (P)

Uptake and Transport System

Phosphorus, is an important constituent of many organic molecules such as nucleic acid, sugars, ATP, and phospholipids, which provides energy and help in the growth and development of living organisms. Plants acquire phosphorus in the inorganic form (Pi) by high affinity transporters (PHTs) and Pi/H+ symporters (Mlodzinska and Zboinska, 2016). In Arabidopsis, PHT gene family is divided into four groups (PHT1, PHT2, PHT3, and PHT4) are involved in different functions. PHT1;1 and PHT1;4 are high affinity transporters which acquire P from the soil, PHT1;5 is responsible for the source to sink translocation, PHT1;8 and PHT1;9 carry out root-shoot Pi mobilization (Nussaume et al., 2011; Ye et al., 2015). PHT2;1 is the low affinity transporter and is involved in the Pi translocation between root and shoot. Other Pi transporter, PHO1 (Phosphate 1), contains SPX domain and EXS [Early Responsive to Dehydration1 (ERD1)], is involved in Pi loading into the xylem as pho1 mutant exhibits lower Pi levels in shoots (Liu et al., 2014; Wege et al., 2016). PHO2 (PHOSPHATE2; ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2) acts as a negative regulator of Pi uptake and degrades phosphate transporters (PHT1;1, PHT1;2, PHT1;3, PHT1;4, PHO1) and phosphate transporter facilitator1 (PHF1; Huang et al., 2013). The identification and detailed investigation of other transporters involved in Pi homeostasis is required to understand the transport, cellular metabolism, and nutrient fluctuations in plants.

The Phosphate Starvation Response 1 (PHR1) is a central regulator of Pi homeostasis and up-regulates the expression of PHT and Pi-starvation induced genes through binding to the PHR1-binding sequences in the promoter region of many Pi-related genes (Chiou and Lin, 2011; Sobkowiak et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013). Under phosphate deficient conditions, systemic and local signaling pathways are activated for the regulation of Pi uptake, assimilation, and redistribution inside the plant (Scheible and Rojas-Triana, 2015). A series of signaling events regulated by different factors take place leading to modulation in root structure architecture/morphology by increasing root hair length as well as lateral root formation to enhance Pi uptake from the external environment (Table 1) (Linkohr et al., 2002; Svistoonoff et al., 2007; Fang et al., 2009; Shukla et al., 2015). In addition to above signaling events, secondary messengers such as Ca2+, inositol polyphosphates (IPs), and reactive oxygen species (ROS) play an important role in regulating Pi homeostasis in plants (Chiou and Lin, 2011). As root development and architecture is a complex trait, detailed studies related to hormonal cross-talk and secondary messengers will help in better understanding of the mechanism and overall plant’s efficiency to adapt and combat nutrient deficiency.

Table 1.

Various signaling pathway components involved in Pi-related response.

| Factor | Signal | Experiment | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR399 overexpression | Long distance | Vascular grafting | Suppression of PHO2; increased Pi transporter; increased Pi acquisition | Lin et al., 2008; Pant et al., 2008, 2009 |

| Pi-deficiency in one of the root partner | Systemic/Local | Split-root | Entire sets of PSI transcripts regulated systemically; other groups of PSI gene transcripts are regulated locally | Thibaud et al., 2010 |

| Shoot Pi concentration | Systemic | Split-root | Cluster root growth; citrate exudation (White Lupin); repression of the plant genes involved in AM symbiosis | Shane et al., 2003; Shane and Lambers, 2006; Breuillin et al., 2010; Balzergue et al., 2011 |

| Auxin | Systemic | Exogenous application in P-sufficient roots | Mimics Pi-deficiency, i.e., reduced primary root length, higher lateral root density, root hair elongation | Gilbert et al., 2000; Williamson et al., 2001; López-Bucio et al., 2002 |

| Ethylene | Systemic | Transcriptome analysis of Pi-deficient plants | Upregulation of ethylene responsive genes; antagonistic to auxin signaling | López-Bucio et al., 2002; Ma et al., 2003; Uhde-Stone et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2003; He et al., 2005; Morcuende et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008; Thibaud et al., 2010 |

| Cytokinin | Systemic | Phosphate deficient | Repress induction of PSI genes; increase in intracellular Pi concentration | Martín et al., 2000; Franco-Zorrilla et al., 2005 |

Regulation of Pi Homeostasis by Small RNA

Various studies identified an array of genes involved in the Pi signaling network mechanisms (Liang et al., 2014). In addition, involvement of sRNAs in regulating the expression of genes involved in phosphate uptake and assimilation in different plant species including Arabidopsis, maize, soybean, rice, and tomato has been demonstrated (Lundmark et al., 2010; Pei et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2013; Gu et al., 2014). Identification of these phosphate starvation responsive miRNA families (Table 2) has been identified via various approaches including high throughput sRNA sequencing. These miRNAs mediate regulation of phosphate uptake, transport, and assimilation in plants through targeting a set of genes. Studies suggest that miRNA families such as miR156, miR159, miR166, miR319, miR395, miR398, miR399, miR447, and miR827 are commonly responsive to Pi-deficiency among different species and are presumably involved in conserved Pi-deficiency signaling networks (Sun et al., 2012; Sunkar et al., 2012). In most of these studies, enhanced levels of miR156, miR399, miR778, miR827, miR2111 and repressed levels of miR169, miR395, and miR398 were observed under Pi-deficiency (Hsieh et al., 2009). However, abundance of miR778 and miR2111 is reduced by approximately twofold after the addition of Pi (Pant et al., 2009). Apart from Pi-deficiency, role of miR2111 has been demonstrated in N-starvation (Liang et al., 2012). Similarly, miR827 and miR399 are responsive to N-starvation and target Nitrogen Limitation Adaptation (NLA) gene and enhances the expression of PHO2 transporter. Analysis of proximal promoters of Pi-responsive MIRNA genes suggest presence of conserved motifs which might be involved in regulated expression under Pi-deficiency (Zeng et al., 2010). Detailed characterization of these cis-elements and interacting proteins will help in the better understanding of the molecular regulation mechanism of genes involved in Pi acquisition and transport.

Table 2.

Plant micro RNA (miRNA) families responsive to Pi-deficiency.

| miRNA families |

Plant species | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated | Down-regulated | ||

| miR156, miR157, miR159, miR163, miR164, miR165, miR166, miR167, miR171, miR172, miR319, miR391, miR393, miR399, miR408, miR447, miR778, miR780, miR822, miR824, miR827, miR828, miR843, miR865, miR866 | miR169, miR395, miR398, miR402, miR779, miR823, miR860, miR2111 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Hsieh et al., 2009; Pant et al., 2009; Lundmark et al., 2010 |

| miR399, miR827 | Oryza sativa | Zhou et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2010 | |

| miR156, miR160, miR166, miR168, miR171, miR395, miR396, miR399, miR437, miR447, miR472, miR477, miR809, miR818, miR830, miR845, miR854, miR857, miR863, miR866, miR896, mir903, miR904, miR1222 | miR159, miR164, miR166, miR167, miR319, miR390, miR395, miR396, miR397, miR447, miR530, miR810, miR818, miR857, miR893, miR895, miR1211 | Lupinus albus | Zhu et al., 2010 |

| miR156, miR157, miR159, miR167, miR168, miR319, miR396, miR474, miR482, miR894, miR1509 | miR160, miR165, miR166, miR168, miR396, miR398, miR834, miR854, miR1118, miR1311, miR1427, miR1436, miR1450, miR1507, miR1508, miR1511, miR1846, miR1858, miR1879, miR1881 | Glycine max | Zeng et al., 2010 |

| miR156, miR157, miR170, miR319, miR393, miR399 | miR160, miR167, miR169, miR317, miR397, miR398, miR408, miR1511, miR1513, miR1515, miR1516, miR2118 | Phaseolus vulgaris | Valdés-López et al., 2010 |

| miR171, miR172, miR394, miR395, miR398, miR399, miR779, miR837, miR839, miR840, miR847, miR860, miR861, miR862, miR867 | miR158, miR169, miR172, miR319, miR398, miR771, miR775, miR158, miR169, miR319, miR172, miR771, miR775 | Solanum lycopersicum | Gu et al., 2010 |

Unique miRNAs are indicated in Bold.

Genes encoding SPX subfamily proteins, SPX-MFS (Major Facility Superfamily) are reported to be involved in the Pi-sensing/transport and are targeted by miR827 (Pacak et al., 2016). In addition, miR398a has been shown to regulate the expression of a set of genes under P, N, and C deficiency and helps in the maintenance of mineral balance in plants (Dugas and Bartel, 2008). Studies also suggest that phloem enriched sRNAs respond to P-deficiency. Grafting studies carried out on Arabidopsis wild type and the miRNA processing hen1-1 mutant plants identified miR399 and miR395 as phloem sap sRNAs that are transported from shoot to root and target genes in the roots of the seedlings exposed to nutrient deficiency (Buhtz et al., 2010). miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional and ubiquitin-mediated post-translational regulatory pathways have been shown to modulate Pi transport activity in response to external Pi status (Lin et al., 2014). Interestingly, responsiveness of many miRNAs is species- and tissues/organs-specific under Pi-deficiency. In response to phosphate starvation, miR395 is down-regulated in the Arabidopsis shoots but up-regulated in the shoots of white lupin (Lupinus albus; Zhu et al., 2010).

Among all Pi-responsive miRNAs, miR399 is the most studied phosphate starvation responsive sRNA which is up-regulated under Pi-stressed conditions (Bari et al., 2006; Chiou et al., 2006; Phillips et al., 2007). In Arabidopsis, all the six members of MIR399 genes (MIR399A–F) are induced under Pi-deficiency (Kuo and Chiou, 2011). Overexpression of miR399 in transgenic Arabidopsis led to the enhanced Pi uptake and allocation to the shoots (Aung et al., 2006; Chiou et al., 2006). Interestingly, overexpression of Arabidopsis miR399 in tomato exhibited increased Pi accumulation and secretion of acid phosphatase in the roots causing hydrolysis of soil organic P and dissolution of Pi (Gao et al., 2010). Studies suggest that miR399 targets three genes; Pi transporter (PHT1;7), a DEAD box helicase and PHO2 which encodes putative ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (UBC) under Pi deficient condition (Fujii et al., 2005). miR399 acts as a positive regulator and enhances Pi uptake and translocation under Pi deficient condition, while PHO2 functions as a negative regulator and suppress these activities to prevent excess Pi uptake under Pi sufficient condition (Lin et al., 2008; Yuan and Liu, 2008). In addition, miR399 also serves as a long-distance signal from shoot to suppress PHO2 expression and maintain Pi homeostasis in plants. Furthermore, miR399 has been shown to function in multiple nutrient deficiency responses in rice. GeneChip analysis of the OsmiR399 overexpressing plants revealed up regulation of number of genes involved in multiple nutrient stress conditions such as iron, potassium, sodium, and calcium (Hu et al., 2015).

In Arabidopsis, the non-protein coding gene IPS1 (Induced by phosphate starvation1) was identified to contain a motif with sequence complementarity to miR399. IPS1 was found to sequester miR399 due to the interrupted pairing of IPS1-miR399. Consequently, overexpression of IPS1 resulted in the reduction of Pi levels in shoots due to the enhanced accumulation of miR399 target PHO2 (Franco-Zorrilla et al., 2007). It is noteworthy to mention that identification and analysis of regulated expression of additional endogenous target mimics will help in developing strategies and approaches to withstand environmental constraints by the plants.

Expression and functional genomics approaches have demonstrated the complex network of regulatory genes involved in Pi-deficiency (Hammond et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2003; Hammond and White, 2008). Under Pi-deficiency, the major transcriptional regulatory system involving PHR1, SIZ1, miR399, and PHO2 has been suggested in Arabidopsis thaliana (Fujii et al., 2005; Schachtman and Shin, 2007). In addition, PHR1-miR399-PHO2 signaling pathway has also been shown to operate in rice in response to Pi-deficiency. OsPHR2, the homolog of AtPHR1, is a key regulator involved in Pi-starvation signaling in rice (Zhou et al., 2008). A recent study suggests that under Pi-deficiency, AtMYB2 regulates miR399f expression by directly binding to MYB-binding site in the promoter region of the miR399f precursor. The over expression of AtMYB2 also affects root system architecture causing reduction in the primary root growth and enhancement in root hair development (Baek et al., 2013).

Interestingly, Pi-responsive miR399 was observed to be induced by Candidatus liberibacter infection which causes Huanglongbing (HLB) disease of citrus. sRNA profiling of infected and healthy sweet orange plants identified number of miRNAs and siRNAs induced in response to the infection. The induction of miR399 is in correspondence to Pi-deficiency in the infected plants as compared to the healthy plants (Zhao et al., 2013). This suggests existence of interplay of sRNAs under nutrient deficiency and biotic stresses in plants.

Various studies demonstrated that miR827 and miR2111 are induced in response to phosphate starvation but not under other nutrient deficiency conditions (Hsieh et al., 2009). miR827 target gene encoding proteins containing SPX domain, which is involved in Pi-sensing, and transport in yeast and xylem loading in plants (Hackenberg et al., 2013). miR2111 target gene encodes F-box protein, which is a component of SCF ubiquitin ligase complexes. Notably, all the three inducible miRNAs (miR399, miR827, and miR2111) target genes involved in the ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation pathway, which suggest that the post-translational regulation of genes is a key component in the adaptive response of Pi-deficiency. Intriguingly, phosphate starvation responsive miRNAs such as miR828 regulates ta-siRNAs (TAS4) transcript which produces clusters of phased transacting, siRNAs (Hsieh et al., 2009). It has been reported that TAS4-siR81(-), which is one of the dominant TAS4 siRNAs, targets the transcripts of a group of MYB transcription factors involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis (Rajagopalan et al., 2006). Anthocyanin accumulation is a common stress response and induction of TAS4-siR81(-) under N deficiency indicates autoregulation mechanism in plants.

Sulfur (S)

Uptake and Transport System

Plants take up sulfur in the form of sulfate (SO42–) from the soil via sulfate transporters located on the epidermal and cortical plasma membrane of the roots (Liu et al., 2009). Sulfate transporter gene family has been characterized in different plant species (Takahashi, 2010; Kumar et al., 2011, 2015). Arabidopsis genome encodes 14 sulfate transporters, which are divided into five groups on the basis of their sequence similarity, substrate affinity, and tissue specific localization (Grossman and Takahashi, 2001; Kumar et al., 2011). Group 1 transporters are high affinity sulfate transporters involved in the uptake of sulfate from the soil (Howarth et al., 2003; Yoshimoto et al., 2007). Group 2 transporters are low affinity sulfate transporters responsible for the long-distance transport of sulfate (Takahashi, 2010). Group 3 comprises transporters that work in cooperation with low affinity transporters and mainly translocate sulfate from root to shoot (Kataoka et al., 2004). Vacuoles are considered to be the ‘store house’ of sulfate, and during sulfate limiting condition, sulfate is mobilized from vacuoles to the cytoplasm. The sulfate efflux transporters are located on the tonoplast and are classified in Group 4 (Zuber et al., 2010). The transporters belonging to group 5 are also termed as molybdenum transporters due to their involvement in transport of molybdenum inside the plant (Shinmachi et al., 2010). Under sulfur deficiency, predominantly, the expression of high affinity transporters (Group 1) increases which helps in uptake of sulfate from the soil to maintain sulfate homeostasis inside the plant (Kumar et al., 2011).

After sulfate acquisition, S is assimilated into the plastid by the sulfur assimilation pathway (Jez et al., 2016). Sulfate is converted to adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (APS) by ATP sulphurylase, the first step of this pathway. Further, sulfate is reduced to sulfite by enzyme APS reductase and subsequently to sulfide by sulfite reductase enzyme. This sulfide is incorporated into cysteine, which is a precursor for various sulfur containing compounds such as phytochelatins, metallothioneins, and glutathiones playing important role in stress tolerance (Leustek and Saito, 1999; Dixit et al., 2015a,b,c).

Regulation of S Homeostasis by Small RNA

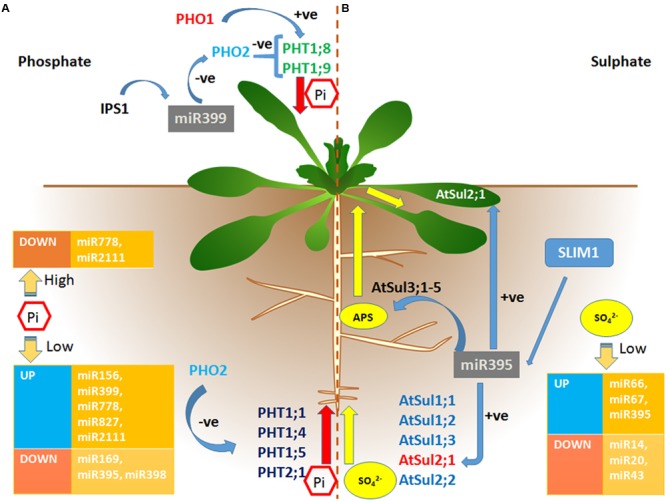

A number of studies have been carried out to identify and validate function of S-responsive miRNAs. These S-responsive miRNAs generally target different transcription factors involved in auxin signaling pathway and stress response (Li et al., 2016) and regulate sulfate uptake, transport and assimilation in plants (Figure 1). Deep sequencing identified 27 conserved miRNAs and five novel miRNAs, which express under SO2 stress in Arabidopsis (Li et al., 2016). The novel miRNAs; miR66 and miR67 were up-regulated more than sixfold whilst miR14, miR20 and miR43 were down-regulated sevenfold in the SO2-treated samples in comparison to control (Table 3). Comparative deep sequencing of Arabidopsis sRNAs treated with different nutrient deficiency including C, N, and S revealed that the targets of differentially expressed miRNAs were related to cellular and metabolic processes, signal transduction, and nutrient homeostasis. miR169b/c, miR826, and miR395 were specifically induced under C, N, and S deficiency, respectively. On the contrary, different miRNAs; miR167, miR172, miR397, miR398, miR399, miR408, miR775, miR827, miR841, miR857, and miR2111 were repressed under the C, N, and S deficient conditions (Liang et al., 2015). Sequencing of sRNA population in Brassica napus identified conserved and novel miRNAs responsive to S deficiency and Cd stress (Huang et al., 2010). This indicated that miRNA genes and their corresponding targets coordinately participate in both the stresses. Deep sequencing analysis of miRNAs in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii identified differential expression of miRNAs under S deficient and sulfur starved conditions (Shu and Hu, 2012). In addition, studies suggest binding of sulfur-responsive transcription factors particularly, Prohibitin (PHB), Squamosa-Promoter Binding (SPB), and Sulfur Limitation 1 (SLIM1) to the promoter of nutrient responsive miRNAs (Panda and Sunkar, 2015).

FIGURE 1.

miRNA mediated regulation of Phosphate and Sulfate uptake, transport and assimilation in plants. (A) Phosphate (Pi) uptake is regulated by phosphate high affinity transporters. PHO1 and PHO2 are responsible for the xylem loading of Pi. PHO2 act as a negative regulator of Pi loading whereas PHO1 helps in Pi loading into xylem. Various miRNAs regulation under Pi starved and sufficient conditions are shown in orange boxes. The miR399 and isoforms act as primary regulator of Pi uptake, transport and assimilation by negatively regulating PHO2 under Pi starved conditions. Induced by phosphate starvation1 (IPS1) pairs with miR399 and causes its sequestration. (B) Sulfate uptake, transport and assimilation involves different transporters. Groups 1 and 2 sulfate transporters are involved in the sulfate uptake from soil to roots. Group 3 is associated with root to shoot transport of sulfate. The expression of various miRNAs under sulfate starved condition has been shown in orange boxes. miR395 has been reported to be sulfate-specific miRNA and acts as a primary regulator of sulfate deficient responsive pathway. Under sulfate deficient condition, miR395 positively regulates expression of a low affinity transporter AtSul2;1 to help in the sulfate uptake and transport to shoot and leaves.

Table 3.

Plant miRNA families responsive to S deficiency.

| miRNA families |

Plant species | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated | Down-regulated | ||

| miR160, miR164, miR169, miR173, miR319, miR395, miR400, miR403, miR771, miR826, mir829, mir833, miR837, miR846, miR864, mir842, miR5638, miR8172 | miR167, miR 171, miR172, miR390, miR391, miR397, miR398, miR399, miR408, miR775, miR825, miR827, miR841, miR845, miR850, miR857, miR863, mR1888, miR2111 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Barciszewska-Pacak et al., 2015; Liang et al., 2015 |

| miR156, miR159, miR164, miR393, miR394, miR395 | miR160, miR167, miR168 | Brassica napus | Huang et al., 2010 |

| miR156, miR159, miR160, miR162, miR164, miR166, miR167, miR168, miR169, miR171, miR172, miR319, miR390, miR393, miR394, miR395, miR396, miR397, miR398, miR399, miR403, miR408, miR530, miR535, miR3627, miR-c4, miRc-10 | Carica papaya | Liang et al., 2013 | |

| miR51, miR62, miR84, miR182, miR196, miR906, miR909, miR910, miR912, miR914, miR1144, miR1147, miR1148, miR1149, miR1150, miR1153, miR1155, miR1156, miR1158, miR1159, miR1160, miR1164, miR1166, miR1172 | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Shu and Hu, 2012 | |

Unique miRNAs are represented in Bold.

Intriguingly, miR395 plays an important role in sulfate homeostasis by regulating the expression of genes involved in the sulfate uptake, transport and assimilation (Chiou, 2007; Zeng et al., 2014). It has been observed that miR395 is specifically responsive to S deficiency (Hsieh et al., 2009). The MIR395 loci present in many monocots and dicots express in the vascular system of roots, root tips, and leaves (Kawashima et al., 2009). Arabidopsis genome encodes six miR395 genes which are located in two clusters (miR395a,b,c and miR395d,e,f) whereas in rice 24 genes encoding miR395 are clustered into four clusters (Jones-Rhoades and Bartel, 2004; Guddeti et al., 2005).

In Arabidopsis, out of four ATP sulphurylases (APSs), APS1,3, and 4 are located in the plastid and APS2 is found in the cytosol (Hatzfeld et al., 2000). miR395 target the mRNAs of three APSs (APS1, APS3, and APS4; Figure 1) which catalyze the initial activation step of sulfate assimilation into cysteine (Jones-Rhoades and Bartel, 2004; Sunkar et al., 2012). This clearly suggests that miR395 regulates the plastidial sulfate assimilation as sulfate is reduced and assimilated into cysteine in the plastid (Rotte and Leustek, 2000). Sulphation reaction occurs in the cytosol in which 5′-adenylsulfate is used for the synthesis of glucosinolates (Chiou, 2007). Under S deficiency, the regulation of miR395 remains elusive as induction of miR395 represses the expression of APS1 (Jones-Rhoades and Bartel, 2004) whereas in Arabidopsis and Brassica roots expression of APS1 and APS3 and total APS activity increases. Moreover, transcript level of APS1 decreases twofold in the shoots of sulfate deficient conditions. Apart from regulating S assimilation, miR395 also regulates S uptake by targeting the gene encoding low affinity sulfate transporter Sul2;1 which is localized in the vascular tissues of roots and leaves (Takahashi et al., 2000; Allen et al., 2005; Kruszka et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2014).

The miR395 overexpression in Arabidopsis suppressed the expression of target genes APS1, APS3, APS4, and Sul2;1 (Liang and Yu, 2010). At the same time, overexpression of OsmiRNA395h in tobacco impaired S homeostasis and affected S distribution among leaves of different ages (Yuan et al., 2016). miR395 overexpressing Brassica napus transgenic plants accumulate higher biomass and sulfur content in Cd treated plants as compared to wild type. In addition, transgenic plants accumulated high level of Cd, with less translocation from root to shoot suggesting miR395 is involved in detoxification of Cd in Brassica napus (Zhang et al., 2013).

Furthermore, the transcription factor of the ethylene-insensitive like (EIL) family, SLIM1, has been observed to directly or indirectly regulate the expression of miR395 (Figure 1) to maintain S homeostasis under deficiency (Kawashima et al., 2011; Matthewman et al., 2012). Under S deficiency, GSH level decreases, which further modulates the expression of genes involved in S metabolism and enhances the expression of miR395. As GSH is an important component of cellular redox signaling, involvement of redox signaling was suggested in the induction of miR395 under S deficiency (Jagadeeswaran et al., 2014). In addition, analysis of miRNA395 over expressing Arabidopsis plants, slim1-1 mutants, and plants with reduced miR395 activity by target mimicry depicted the interplay of SLIM1 and miR395 in the sulfate assimilation in Arabidopsis (Todesco et al., 2010; Kawashima et al., 2011). Thus, the S-deficiency induced expression of miR395 represents a link between redox signaling and SLIM1 transcription factor.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

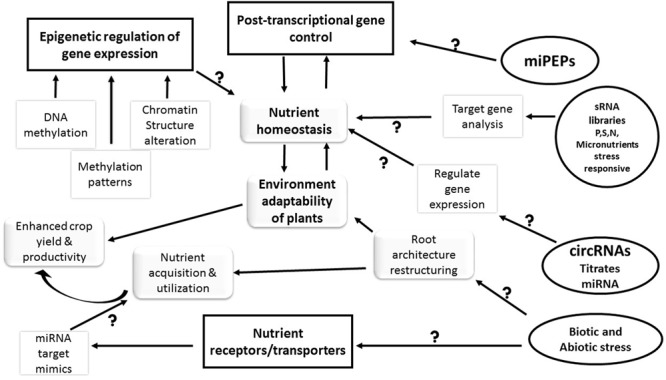

Plants as sessile organisms have evolved several mechanisms to fulfill any type of nutrient deficiency. The roots and other aerial parts of the plant act as an extension for various signaling cascades to form a nexus to adapt to nutrient stress. miRNAs being an important component of this nexus, have been found to be riboregulatory in regulation of nutrient sensing, transport and assimilation, such as miR395 and miR399 for S and P, respectively. In plants, though lesser number of miRNA gene clusters exist, existence of miR399 and miR395 clusters reflect the occurrence of gene duplication events during evolution. This may be the reason for the coordinated regulation of these miRNAs under nutrient deficiency in plants. Though, a large number of nutrient deficiency responsive miRNAs have been identified, role of these miRNAs in regulating the nutrient stress needs to be studied. To elucidate various components and networks involved in nutrient homeostasis in plants, there is need to study different regulatory aspects (Figure 2) in detail. Future studies required in these areas are summarized below.

FIGURE 2.

Future perspectives in regulation of nutrient uptake/transport and assimilation in plants. The figure illustrates the role of various factors in maintenance of nutrient uptake, assimilation and transport. The post-transcriptional and epigenetic modifications have driven the nutrient sensing, uptake and transport in the plants. However, new perspectives in the nutrient regulation such as miRNA-PEPs (miPEPs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), and micro RNA (miRNA) target mimicry are required to generate more information about the pathways and regulators of nutrient homeostasis in plants. The information acquired in these areas will eventually lead to better nutrient acquisition and utilization by the crop plants. The square boxes are the known factors whereas the factors in circular/oval boxes represent the knowledge voids (questions marks) that need further investigation in near future. The arrows represent the relationship between the interconnected events.

Apart from genetic regulation of gene expression, the epigenetic regulation also occurs in plants to counter nutrient deficiency as well as sufficiency. Studies have identified that alteration in chromatin structure and methylation pattern govern environmental adaptability in plants under nutrient deficiency (Sirohi et al., 2016). It has been reported that miRNAs also regulate gene expression via DNA methylation. For example, miR165/166 regulate the expression of target genes by DNA methylation (Bao et al., 2004). Thus, investigation of epigenetic control during nutrient deficiency can offer clear and insightful information about the plant adaptability toward environmental constraints.

The recent study in the field of plant interactome suggested an insight into the global organization of various biological processes that constitute a community network of different hypothetical functional links between proteins and pathways (Arabidopsis Interactome Mapping Consortium, 2011; Reichel et al., 2016). Such studies are required to establish sRNA-protein and protein-protein interaction networks to understand sRNA-mediated regulation and dynamic rewiring of processes such as nutrient sensing, uptake, transport, assimilation, and interactions occurring in plants.

In-depth sequencing of sRNA libraries and target gene analysis under single or multiple nutrient stress might help in the better understanding the cohort of sRNA-mediated stress responses in plant. Identification and characterization of endogenous target mimics for nutrient responsive miRNAs may provide deeper understanding about nutrient acquisition and utilization in plants. Recently, miRNA-PEPs (miPEP) have been shown to regulate a number of miRNAs (Lauressergues et al., 2015; Couzigou et al., 2016). It will be interesting to study whether such miPEPs are encoded by MIR genes responsive to nutrient deficiency and play role in nutrient homeostasis. The circular RNAs (circRNAs), a product of back-splicing of precursor mRNA; interfering eukaryotic processes by interference of splicing and transcription and also titrates miRNAs has been reported to regulate and reshape the gene expression (Lu et al., 2015; Wang and Wang, 2015; Chen, 2016). Thus, a combination of various different approaches using high throughput technologies could help us uncover the master regulators and deregulators of plant nutrient stress.

An insight into the complexity of nutrient-plant interaction, the root system restructuring and the nutrient stress is essential for the improvement of crop yield and productivity as these depend upon ability of plant to utilize surrounding nutrients. The in situ imaging studies employing non-destructive X-ray based techniques (Perret et al., 2007) will be useful in elucidation of the root system growth dynamics and their restructuring upon various nutrient stresses. This will provide a que for plant breeders in future to develop hybrids with well-developed root architecture that might withstand adversity against many nutrient stresses and drought conditions. Thus, the exploration of precise mechanisms involved in sensing, signaling, and cross-talk of nutrients and miRNAs will help in developing strategies for improving the nutrient use efficiency and increasing crop productivity required for the global sustainability and food security.

Author Contributions

SK and PT conceived the idea and planned the manuscript. SK, SV, and PT wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, as Network Project (BSC-0107). SK thankfully acknowledges the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India, New Delhi for the DST-INSPIRE Faculty Award.

References

- Abdel-Ghany S. E., Pilon M. (2008). MicroRNA-mediated systemic down-regulation of copper protein expression in response to low copper availability in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 283 15932–15945. 10.1074/jbc.M801406200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen E., Xie Z., Gustafson A. M., Carrington J. C. (2005). MicroRNA-directed phasing during trans-acting siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell 121 207–221. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabidopsis Interactome Mapping Consortium (2011). Evidence for network evolution in an Arabidopsis interactome map. Science 333 601–607. 10.1126/science.1203877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aung K., Lin S. I., Wu C. C., Huang Y. T., Su C. L., Chiou T. J. (2006). pho2, a phosphate overaccumulator, is caused by a nonsense mutation in a microRNA399 target gene. Plant Physiol. 141 1000–1011. 10.1104/pp.106.078063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek D., Kim M. C., Chun H. J., Kang S., Park H. C., Shin G., et al. (2013). Regulation of miR399f transcription by AtMYB2 affects phosphate starvation responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 161 362–373. 10.1104/pp.112.205922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzergue C., Puech-Pagès V., Bécard G., Rochange S. F. (2011). The regulation of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis by phosphate in pea involves early and systemic signaling events. J. Exp. Bot. 62 1049–1060. 10.1093/jxb/erq335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao N., Lye K., Barton M. K. (2004). MicroRNA binding sites in Arabidopsis class III HD-ZIP m-RNAs are required for methylation of the template chromosomes. Dev. Cell 7 653–662. 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barciszewska-Pacak M., Milanowska K., Knop K., Bielewicz D., Nuc P., Plewka P., et al. (2015). Arabidopsis microRNA expression regulation in a wide range of abiotic stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 6:e410 10.3389/fpls.2015.00410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari R., Pant B. D., Stitt M., Scheible W. R. (2006). PHO2, microRNA399, and PHR1 define a phosphate-signaling pathway in plants. Plant Physiol. 141 988–999. 10.1104/pp.106.079707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuillin F., Schramm J., Hajirezaei M., Ahkami A., Favre P., Druege U., et al. (2010). Phosphate systemically inhibits development of arbuscular mycorrhiza in Petunia hybrida and represses genes involved in mycorrhizal functioning. Plant J. 64 1002–1017. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04385.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhtz A., Pieritz J., Springer F., Kehr J. (2010). Phloem small RNAs, nutrient stress responses, and systemic mobility. BMC Plant Biol. 10:e64 10.1186/1471-2229-10-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. L. (2016). The biogenesis and emerging roles of circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17 205–211. 10.1038/nrm.2015.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou T. J. (2007). The role of microRNAs in sensing nutrient stress. Plant Cell Environ. 30 323–332. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01643.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou T. J., Aung K., Lin S. I., Wu C. C., Chiang S. F., Su C. L. (2006). Regulation of phosphate homeostasis by microRNA in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18 412–421. 10.1105/tpc.105.038943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou T. J., Lin S. I. (2011). Signaling network in sensing phosphate availability in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 62 185–206. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combier J. P., Frugier F., Billy F., Boualem A., El-Yahyaoui F., Moreau S., et al. (2006). MtHAP2-1 is a key transcriptional regulator of symbiotic nodule development regulated by microRNA169 in Medicago truncatula. Genes Dev. 20 3084–3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couzigou J. M., Andre O., Guillotin B., Alexandre M., Combier J. P. (2016). Use of microRNA-encoded peptide miPEP172c to stimulate nodulation in soybean. New Phytol. 211 379–381. 10.1111/nph.13991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit G., Singh A. P., Kumar A., Dwivedi S., Deeba F., Kumar S., et al. (2015a). Sulfur alleviates arsenic toxicity by reducing its accumulation and modulating proteome, amino acids and thiol metabolism in rice leaves. Sci. Rep. 5:e16205 10.1038/srep16205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit G., Singh A. P., Kumar A., Mishra S., Dwivedi S., Kumar S., et al. (2015b). Reduced arsenic accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.) shoot involves sulfur mediated improved thiol metabolism, antioxidant system and altered arsenic transporters. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 99 86–96. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit G., Singh A. P., Kumar A., Singh P. K., Kumar S., Dwivedi S., et al. (2015c). Sulfur mediated reduction of arsenic toxicity involves efficient thiol metabolism and the antioxidant defense system in rice. J. Hazard. Mater. 298 241–251. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas D. V., Bartel B. (2008). Sucrose induction of Arabidopsis miR398 represses two Cu/Zn superoxide dismutases. Plant Mol. Biol. 67 403–417. 10.1007/s11103-008-9329-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z., Shao C., Meng Y., Wu P., Chen M. (2009). Phosphate signaling in Arabidopsis and Oryza sativa. Plant Sci. 176 170–180. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.09.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Zorrilla J. M., Martín A. C., Leyva A., Paz-Ares J. (2005). Interaction between phosphate-starvation, sugar, and cytokinin signaling in Arabidopsis and the roles of cytokinin receptors CRE1/AHK4 and AHK3. Plant Physiol. 138 847–857. 10.1104/pp.105.060517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Zorrilla J. M., Valli A., Todesco M., Mateos I., Puga M. I., Rubio-Somoza I., et al. (2007). Target mimicry provides a new mechanism for regulation of microRNA activity. Nat. Genet. 39 1033–1037. 10.1038/ng2079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H., Chiou T. J., Lin S. I, Aung K., Zhu J. K. (2005). A miRNA involved in phosphate-starvation response in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 15 2038–2042. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao N., Su Y., Min J., Shen W., Shi W. (2010). Transgenic tomato overexpressing ath-miR399d has enhanced phosphorus accumulation through increased acid phosphatase and proton secretion as well as phosphate transporters. Plant Soil 334 123–136. 10.1007/s11104-009-0219-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert G. A., Knight J. D., Vance C. P., Allan D. L. (2000). Proteoid root development of phosphorus deficient lupin is mimicked by auxin and phosphonate. Ann. Bot. 85 921–928. 10.1006/anbo.2000.1133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman A., Takahashi H. (2001). Macronutrient utilization by photosynthetic eukaryotes and the fabric of interactions. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 52 163–210. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber B. D., Giehl R. F. H., Friedel S., von Wirén N. (2013). Plasticity of the Arabidopsis root system under nutrient deficiencies. Plant Physiol. 163 161–179. 10.1104/pp.113.218453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu M., Liu W., Meng Q., Zhang W. Q., Chen A. Q., Sun S. B., et al. (2014). Identification of microRNAs in six solanaceous plants and their potential link with phosphate and mycorrhizal signalings. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 56 1164–1178. 10.1111/jipb.12233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu M., Xu K., Chen A., Zhu Y., Tang G., Xu G. (2010). Expression analysis suggests potential roles of microRNAs for phosphate and arbuscular mycorrhizal signaling in Solanum lycopersicum. Physiol. Plant. 138 226–237. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01320.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guddeti S., Zhang D. C., Li A. L., Leseberg C. H., Hui K., Xiao G. L., et al. (2005). Molecular evolution of the rice miR395 gene family. Cell Res. 15 631–638. 10.1038/sj.cr.7290333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackenberg M., Huang P. J., Huang C. Y., Shi B. J., Gustafson P., Langridge P. A. (2013). Comprehensive expression profile of microRNAs and other classes of non-coding small RNAs in barley under phosphorous-deficient and -sufficient conditions. DNA Res. 20 109–125. 10.1093/dnares/dss037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond J. P., Bennett M. J., Bowen H. C., Broadley M. R., Eastwood D. C., May S. T., et al. (2003). Changes in gene expression in Arabidopsis shoots during phosphate starvation and the potential for developing smart plants. Plant Physiol. 132 578–596. 10.1104/pp.103.020941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond J. P., White P. J. (2008). Sucrose transport in the phloem: integrating root responses to phosphorus starvation. J. Exp. Bot. 59 93–109. 10.1093/jxb/erm221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzfeld Y., Lee S., Lee M., Leustek T., Saito K. (2000). Functional characterization of a gene encoding a fourth ATP sulfurylase isoform from Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene 248 51–58. 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00132-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L., Hannon G. J. (2004). MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5 522–531. 10.1038/nrg1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z., Ma Z., Brown K. M., Lynch J. P. (2005). Assessment of inequality of root hair density in Arabidopsis thaliana using the Gini coefficient: a close look at the effect of phosphorus and its interaction with ethylene. Ann. Bot. 95 287–293. 10.1093/aob/mci024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth J. R., Fourcroy P., Davidian J. C., Smith F. W., Hawkesford M. J. (2003). Cloning of two contrasting high-affinity sulfate transporters from tomato induced by low sulfate and infection by the vascular pathogen Verticillium dahliae. Planta 218 58–64. 10.1007/s00425-003-1085-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh L. C., Lin S. I., Shih A. C. C., Chen J. W., Lin W. Y., Tseng C. Y., et al. (2009). Uncovering small RNA-mediated responses to phosphate deficiency in Arabidopsis by deep sequencing. Plant Physiol. 151 2120–2132. 10.1104/pp.109.147280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., Wang W., Deng K., Li H., Zhang Z., Chu C. (2015). MicroRNA399 is involved in multiple nutrient starvation responses in rice.Front. Plant Sci. 6:e188 10.3389/fpls.2015.00188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. Q., Xiang A. L., Che L. L., Chen S., Li H., Song J. B., et al. (2010). A set of miRNAs from Brassica napus in response to sulphate deficiency and cadmium stress. Plant Biotechnol. J. 8 887–899. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00517.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T. K., Han C. L., Lin S. I., Chen Y. J., Tsai Y. C., Chen Y. R., et al. (2013). Identification of downstream components of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme PHOSPHATE2 by quantitative membrane proteomic in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 25 4044–4060. 10.1105/tpc.113.115998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagadeeswaran G., Li Y. F., Sunkar R. (2014). Redox signaling mediates the expression of a sulfate-deprivation-inducible microRNA395 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 77 85–96. 10.1111/tpj.12364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jez J. M., Ravilious G. E., Herrmann J. (2016). Structural biology and regulation of the plant sulfation pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 259 31–38. 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Rhoades M. W., Bartel D. P. (2004). Computational identification of plant microRNAs and their targets, including a stress-induced miRNA. Mol. Cell 14 787–799. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka T., Watanabe-Takahashi A., Hayashi N., Ohnishi M., Mimura T., Buchner P., et al. (2004). Vacuolar sulfate transporters are essential determinants controlling internal distribution of sulfate in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16 2693–2704. 10.1105/tpc.104.023960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima C. G., Matthewman C. A., Huang S., Lee B. R., Yoshimoto N., Koprivova A., et al. (2011). Interplay of SLIM1 and miR395 in the regulation of sulfate assimilation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 66 863–876. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04547.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima C. G., Yoshimoto N., Maruyama-Nakashita A., Tsuchiya Y. N., Saito K., Takahashi H., et al. (2009). Sulphur starvation induces the expression of microRNA-395 and one of its target genes but in different cell types. Plant J. 57 313–321. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03690.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khraiwesh B., Zhu J.-K., Zhu J. (2012). Role of miRNAs and siRNAs in biotic and abiotic stress responses of plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1819 137–148. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.05.00 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-J., Lynch J. P., Brown K. M. (2008). Ethylene insensitivity impedes a subset of responses to phosphorus deficiency in tomato and petunia. Plant Cell Environ. 31 1744–1755. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01886.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W. W., Yang Z. M. (2010). Identification of iron-deficiency responsive microRNA genes and cis-elements in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48 153–159. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruszka K., Pieczynskia M., Windels D., Bielewicz D., Jarmolowski A., Szweykowska-Kulinska Z. (2012). Role of microRNAs and other sRNAs of plants in their changing environments. J. Plant Physiol. 169 1664–1672. 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Asif M. H., Chakrabarty D., Tripathi R. D., Dubey R. S., Trivedi P. K. (2015). Comprehensive analysis of regulatory elements of the promoters of rice sulfate transporter gene family and functional characterization of OsSul1;1 promoter under different metal stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 10:e990843 10.4161/15592324.2014.990843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Asif M. H., Chakrabarty D., Tripathi R. D., Trivedi P. K. (2011). Differential expression and alternative splicing of rice sulphate transporter family members regulate sulphur status during plant growth, development and stress conditions. Funct. Integr. Genomics 11 259–273. 10.1007/s10142-010-0207-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo H. F., Chiou T. J. (2011). The role of microRNAs in phosphorus deficiency signaling. Plant Physiol. 156 1016–1024. 10.1104/pp.111.175265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauressergues D., Couzigou J. M., Clemente H. S., Martinez Y., Dunand C., Becard G., et al. (2015). Primary transcripts of microRNAs encode regulatory peptides. Nature 520 90–93. 10.1038/nature14346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leustek T., Saito K. (1999). Sulfate transport and assimilation in plants. Plant Physiol. 120 637–644. 10.1104/pp.120.3.637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Xue M., Yi H. (2016). Uncovering microRNA-mediated response to SO2 stress in Arabidopsis thaliana by deep sequencing. J. Hazard. Mater. 316 178–185. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C., Wang J., Zhao J., Tian J., Liao H. (2014). Control of phosphate homeostasis through gene regulation in crops. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 21 59–66. 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G., Ai Q., Yu D. (2015). Uncovering miRNAs involved in crosstalk between nutrient deficiencies in Arabidopsis. Sci. Rep. 5:e11813 10.1038/srep11813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G., He H., Yu D. (2012). Identification of nitrogen starvation responsive miRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 7:e48951 10.1371/journal.pone.0048951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G., Li Y., He H., Wang F., Yu D. (2013). Identification of miRNAs and miRNA-mediated regulatory pathways in Carica papaya. Planta 238 739–752. 10.1007/s00425-013-1929-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G., Yu D. (2010). Reciprocal regulation among miR395, APS, and SULTR2;1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal. Behav. 5 1257–1259. 10.4161/psb.5.10.12608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S. I., Chiang S. F., Lin W. Y., Chen J. W., Tseng C. Y., Wu P. C., et al. (2008). Regulatory network of microRNA399 and PHO2 by systemic signaling. Plant Physiol. 147 732–746. 10.1104/pp.108.116269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S. I., Santi C., Jobet E., Lacut E., El Kholti N., Karlowski W. M., et al. (2010). Complex regulation of two target genes encoding SPX-MFS proteins by rice miR827 in response to phosphate starvation. Plant Cell Physiol. 51 2119–2131. 10.1093/pcp/pcq170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W. Y., Huang T. K., Leong S. J., Chiou T. J. (2014). Long-distance call from phosphate: systemic regulation of phosphate starvation responses. J. Exp. Bot. 65 1817–1827. 10.1093/jxb/ert431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkohr B. I., Williamson L. C., Fitter A. H., Leyser H. M. O. (2002). Nitrate and phosphate availability and distribution have different effects on root system architecture of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 29 751–760. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01251.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T. Y., Chang C. Y., Chiou T. J. (2009). The long-distance signaling of mineral macronutrients. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12 312–319. 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T. Y., Lin W. Y., Huang T. K., Chiou T. J. (2014). MicroRNA-mediated surveillance of phosphate transporters on the move. Trends Plant Sci. 19 647–655. 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Bucio J., Hernández-Abreu E., Sánchez-Calderón L., Nieto-Jacobo M. F., Simpson J., Herrera-Estrella L. (2002). Phosphate availability alters architecture and causes changes in hormone sensitivity in the Arabidopsis root system. Plant Physiol. 129 244–256. 10.1104/pp.010934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T., Cui L., Zhou Y., Zhu C., Fan D., Gong H., et al. (2015). Transcriptome-wide investigation of circular RNAs in rice. RNA 21 2076–2087. 10.1261/rna.052282.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig U., Frommer W. B. (2002). Genes and proteins for solute transport and sensing. Arabidopsis Book 1:e0092 10.1199/tab.0092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundmark M., Korner C. J., Nielsen T. H. (2010). Global analysis of microRNA in Arabidopsis in response to phosphate starvation as studied by locked nucleic acid-based microarrays. Physiol. Plant 140 57–68. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2010.01384.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J. P. (2011). Root phenes for enhanced soil exploration and phosphorus acquisition: tools for future crops. Plant Physiol. 156 1041–1049. 10.1104/pp.111.175414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z., Baskin T. I., Brown K. M., Lynch J. P. (2003). Regulation of root elongation under phosphorus stress involves changes in ethylene responsiveness. Plant Physiol. 131 1381–1390. 10.1104/pp.012161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y., Xue X. Y., Chen X. Y. (2009). Are small RNAs a big help to plants? Sci. China C Life Sci. 52 212–223. 10.1007/s11427-009-0034-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín A. C., del Pozo J. C., Iglesias J., Rubio V., Solano R., de La Peña A., et al. (2000). Influence of cytokinins on the expression of phosphate starvation responsive genes in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 24 559–567. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00893.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthewman C. A., Kawashima C. G., Huska D., Csorba T., Dalmay T., Kopriva S. (2012). miR395 is a general component of the sulfate assimilation regulatory network in Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett. 586 3242–3248. 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.06.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnikova N. V., Dmitriev A. A., Belenikin M. S., Koroban N. V., Speranskaya A. S., Krinitsina A. A., et al. (2016). Identification, expression analysis, and target prediction of flax genotroph microRNAs under normal and nutrient stress conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 7:399 10.3389/fpls.2016.00399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlodzinska E., Zboinska M. (2016). Phosphate uptake and allocation–a closer look at Arabidopsis thaliana L. and Oryza sativa L. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1198 10.3389/fpls.2016.01198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcuende R., Bari R., Gibon Y., Zheng W., Pant B. D., Bläsing O., et al. (2007). Genome-wide reprogramming of metabolism and regulatory networks of Arabidopsis in response to phosphorus. Plant Cell Environ. 30 85–112. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01608.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli C., Lemieux C., Jorgensen R. (1990). Introduction of a chimeric chalcone synthase gene into petunia results in reversible co-suppression of homologous genes in trans. Plant Cell 2 279–289. 10.1105/tpc.2.4.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath M., Tuteja N. (2016). NPKS uptake, sensing, and signaling and miRNAs in plant nutrient stress. Protoplasma 253 767–786. 10.1007/s00709-015-0845-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussaume L., Kanno S., Javot H., Marin E., Pochon N., Ayadi A., et al. (2011). Phosphate import in plants: focus on the PHT1 transporters. Front. Plant Sci. 2:83 10.3389/fpls.2011.00083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacak A., Barciszewska-Pacak M., Swida-Barteczka A., Kruszka K., Sega P., Milanowska K., et al. (2016). Heat stress affects Pi-related genes expression and inorganic phosphate deposition/accumulation in Barley. Front. Plant Sci. 7:e926 10.3389/fpls.2016.00926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda S. K., Sunkar R. (2015). Nutrient- and other stress-responsive microRNAs in plants: role for thiol-based redox signalling. Plant Signal. Behav. 10:e1010916 10.1080/15592324.2015.1010916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant B. D., Buhtz A., Kehr J., Scheible W. R. (2008). MicroRNA399 is a long-distance signal for the regulation of plant phosphate homeostasis. Plant J. 53 731–738. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03363.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant B. D., Musialak-lange M., Nuc P., May P., Buhtz A., Kehr J., et al. (2009). Identification of nutrient-responsive Arabidopsis and rapeseed microRNAs by comprehensive real-time polymerase chain reaction profiling and small RNA sequencing. Plant Physiol. 150 1541–1555. 10.1104/pp.109.139139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S., Datta S. K., Datta K. (2015). miRNA regulation of nutrient homeostasis in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 6:232 10.3389/fpls.2015.00232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei L., Jin Z., Li K., Yin H., Wang J., Yang A. (2013). Identification and comparative analysis of low phosphate tolerance associated microRNAs in two maize genotypes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 70 221–234. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.05.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perret J., Al-Belushi M., Deadman M. (2007). Non-destructive visualisation and quantification of roots using computed tomography. Soil Biol. Biochem. 39 391–399. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.07.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J. R., Dalmay T., Bartels D. (2007). The role of small RNAs in abiotic stress. FEBS Lett. 581 3592–3597. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan R., Vaucheret H., Trejo J., Bartel D. P. (2006). A diverse and evolutionarily fluid set of microRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 20 3407–3425. 10.1101/gad.1476406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel M., Liao Y., Rettel M., Ragan C., Evers M., Alleaume A.-M., et al. (2016). In planta determination of the mRNA-binding proteome of Arabidopsis etiolated seedlings. Plant Cell 28 2435–2452. 10.1105/tpc.16.00562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotte C., Leustek T. (2000). Differential subcellular localization and expression of ATP sulfurylase and 5’-adenylylsulfate reductase during ontogenesis of Arabidopsis leaves indicates that cytosolic and plastid forms of ATP sulfurylase may have specialized functions. Plant Physiol. 124 715–724. 10.1104/pp.124.2.715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saier M. H., Jr., Reddy V. S., Tsu B. V., Ahmed M. S., Li C., Gabriel M. H. (2016). The Transporter Classification Database (TCDB): recent advances. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 D372–D379. 10.1093/nar/gkv1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A., Yamaji N., Ma J. F. (2016). Transporters involved in mineral nutrient uptake in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 67 3645–3653. 10.1093/jxb/erw060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachtman D. P., Shin R. (2007). Nutrient sensing and signaling: NPKS. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 58 47–69. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheible W. R., Rojas-Triana M. (2015). “Sensing, signaling and control of phosphate starvation in plants: molecular players and application,” in Annual Plant Reviews: Phosphorus Metabolism in Plants in the Post-Genomic Era: From Gene to Ecosystem Vol. 48 eds Plaxton W. C., Lambers H. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; ). [Google Scholar]

- Shane M. W., DeVos M., De Roock S., Lambers H. (2003). Shoot P status regulates cluster-root growth and citrate exudation in Lupinus albus grown with a divided root system. Plant Cell Environ. 26 265–273. 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.00957.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shane M. W., Lambers H. (2006). Systemic suppression of cluster-root formation and net P-uptake rates in Grevillea crithmifolia at elevated P supply: a proteacean with resistance for developing symptoms of ‘P toxicity’. J. Exp. Bot. 57 413–423. 10.1093/jxb/erj004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D., Tiwari M., Lakhwani D., Tripathi R. D., Trivedi P. K. (2015). Differential expression of microRNAs by arsenate and arsenite stress in natural accessions of rice. Metallomics 7 174–187. 10.1039/C4MT00264D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D., Tiwari M., Pandey A., Bhatia C., Sharma A., Trivedi P. K. (2016). MicroRNA858 is a potential regulator of phenylpropanoid pathway and plant development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 171 944–959. 10.1104/pp.15.01831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinmachi F., Buchner P., Stroud J. L., Parmar S., Zhao F. J., McGrath S. P., et al. (2010). Influence of sulfur deficiency on the expression of specific sulfate transporters and the distribution of sulfur, selenium and molybdenum in wheat. Plant Physiol. 153 327–336. 10.1104/pp.110.153759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu L., Hu Z. (2012). Characterization and differential expression of microRNAs elicited by sulfur deprivation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. BMC Genomics 13:108 10.1186/1471-2164-13-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla T., Kumar S., Khare R., Tripathi R. D., Trivedi P. K. (2015). Natural variations in expression of regulatory and detoxification related genes under limiting phosphate and arsenate stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 6:e898 10.3389/fpls.2015.00898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirohi G., Pandey B. K., Deveshwar P., Giri J. (2016). Emerging trends in epigenetic regulation of nutrient deficiency response in plants. Mol. Biotechnol. 58 159–171. 10.1007/s12033-016-9919-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobkowiak L., Bielewicz D., Malecka E. M., Jacobsen I., Albrechtsen M., Szweykowska-Kulinska Z., et al. (2012). The role of the P1BS element containing promoter-driven genes in Pi transport and homeostasis in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 3:e58 10.3389/fpls.2012.00058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S. B., Gu M., Cao Y., Huang X. P., Zhang X., Ai P. H., et al. (2012). A constitutive expressed phosphate transporter, OsPht1;1, modulates phosphate uptake and translocation in phosphate-replete rice. Plant Physiol. 159 1571–1581. 10.1104/pp.112.196345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunkar R., Chinnusamy V., Zhu J., Zhu J. K. (2007). Small RNAs as big players in plant abiotic stress responses and nutrient deprivation. Trends Plant Sci. 12 301–309. 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunkar R., Li Y. F., Jagadeeswaran G. (2012). Functions of microRNAs in plant stress responses. Trends Plant Sci. 17 196–203. 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svistoonoff S., Creff A., Reymond M., Sigoillot-Claude C., Ricaud L., Blanchet A., et al. (2007). Root tip contact with low-phosphate media reprograms plant root architecture. Nat. Genet. 39 792–796. 10.1038/ng2041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H. (2010). Regulation of sulfate transport and assimilation in plants. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 281 129–159. 10.1016/S1937-6448(10)81004-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H., Watanabe-Takahashi A., Smith F. W., Blake-Kalff M., Hawkesford M. J., Saito K. (2000). The roles of three functional sulphate transporters involved in uptake and translocation of sulphate in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 23 171–182. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00768.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibaud M. C., Arrighi J. F., Bayle V., Chiarenza S., Creff A., Bustos R., et al. (2010). Dissection of local and systemic transcriptional responses to phosphate starvation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 64 775–789. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04375.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari M., Sharma D., Trivedi P. K. (2014). Artificial microRNA mediated gene silencing in plants: progress and perspectives. Plant Mol. Biol. 86 1–18. 10.1007/s11103-014-0224-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todesco M., Rubio-Somoza I., Paz-Ares J., Weigel D. (2010). A collection of target mimics for comprehensive analysis of microRNA function in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 6:e1001031 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhde-Stone C., Zinn K. E., Ramirez-Yáñez M., Li A., Vance C. P., Allan D. L. (2003). Nylon filter arrays reveal differential gene expression in proteoid roots of white lupin in response to phosphorus deficiency. Plant Physiol. 131 1064–1079. 10.1104/pp.102.016881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdés-López O., Yang S. S., Aparicio-Fabre R., Graham P. H., Reyes J. L., Vance C. P., et al. (2010). MicroRNA expression profile in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) under nutrient deficiency stresses and manganese toxicity. New Phytol. 187 805–818. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03320.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Sanchez M. A., Liu J., Hannon G. J., Parker R. (2006). Control of translation and mRNA degradation by miRNAs and siRNAs. Genes Dev. 20 515–524. 10.1101/gad.139980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaucheret H., Fagard M. (2001). Transcriptional gene silencing in plants: targets, inducers and regulators. Trends Genet. 17 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Sun J., Miao J., Guo J., Shi Z., He M., et al. (2013). A wheat phosphate starvation response regulator Ta-PHR1 is involved in phosphate signalling and increases grain yield in wheat. Ann. Bot. 111 1139–1153. 10.1093/aob/mct080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Li X., Zhang S., Korpelainen H., Li C. (2016). Physiological and transcriptional responses of two contrasting Populus clones to nitrogen stress. Tree Physiol. 36 628–642. 10.1093/treephys/tpw019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wang Z. (2015). Efficient backsplicing produces translatable circular mRNAs. RNA 21 172–179. 10.1261/rna.048272.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wege S., Khan G. A., Jung J. Y., Vogiatzaki E., Pradervand S., Aller I., et al. (2016). The EXS domain of PHO1 participates in the response of shoots to phosphate deficiency via a root-to-shoot signal. Plant Physiol. 170 385–400. 10.1104/pp.15.00975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson L. C., Ribrioux S. P., Fitter A. H., Leyser H. M. (2001). Phosphate availability regulates root system architecture in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 126 875–882. 10.1104/pp.126.2.875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P., Ma L., Hou X., Wang M., Wu Y., Liu F., et al. (2003). Phosphate starvation triggers distinct alterations of genome expression in Arabidopsis roots and leaves. Plant Physiol. 132 1260–1271. 10.1104/pp.103.021022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F., Liu Q., Chen L., Kuang J., Walk T., Wang J., et al. (2013). Genome-wide identification of soybean microRNAs and their targets reveals their organ specificity and responses to phosphate starvation. BMC Genomics 14:e66 10.1186/1471-2164-14-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z., Hossain M. S., Wang J., Valdés-López O., Liang Y., Libault M., et al. (2013). miR172 regulates soybean nodulation. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 26 1371–1377. 10.1094/MPMI-04-13-0111-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y., Yuan J., Chang X., Yang M., Zhang L., Lu K., et al. (2015). The phosphate transporter gene OsPht1;4 is involved in phosphate homeostasis in rice. PLoS ONE 10:e0126186 10.1371/journal.pone.0126186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto N., Inoue E., Watanabe-Takahashi A., Saito K., Takahashi H. (2007). Posttranscriptional regulation of high-affinity sulfate transporters in Arabidopsis by sulfur nutrition. Plant Physiol. 145 378–388. 10.1104/pp.107.105742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H., Liu D. (2008). Signaling components involved in plant responses to phosphate starvation. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 50 849–859. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00709.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan N., Yuan S., Li Z., Li D., Hu Q., Luo H. (2016). Heterologous expression of a rice miR395 gene in Nicotiana tabacum impairs sulfate homeostasis. Sci. Rep. 6:e28791 10.1038/srep28791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H., Wang G., Hu X., Wang H., Du L., Zhu Y. (2014). Role of microRNAs in plant responses to nutrient stress. Plant Soil 374 1005–1021. 10.1007/s11104-013-1907-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H. Q., Zhu Y. Y., Huang S. Q., Yang Z. M. (2010). Analysis of phosphorus-deficient responsive miRNAs and cis elements from soybean (Glycine max L.). J. Plant Physiol. 167 1289–1297. 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. W., Song J. B., Shu X. X., Zhang Y., Yang Z. M. (2013). miR395 is involved in detoxification of cadmium in Brassica napus. J. Hazard. Mater. 25 204–211. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.01.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. J., Lynch J. P., Brown K. M. (2003). Ethylene and phosphorus availability have interacting yet distinct effects on root hair development. J. Exp. Bot. 54 2351–2361. 10.1093/jxb/erg250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Liu X., Guo C., Gu J., Xiao K. (2013). Identification and characterization of micro RNAs from wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under phosphorus deprivation. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 22 113–123. 10.1007/s13562012-0117-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Jiao F. C., Wu Z. C., Li Y. Y., Wang X. M., He X. W., et al. (2008). OsPHR2 is involved in phosphate-starvation signaling and excessive phosphate accumulation in shoots of plants. Plant Physiol. 146 1673–1686. 10.1104/pp.107.111443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y. Y., Zeng H. Q., Dong C. X., Yin X. M., Shen Q. R., Yang Z. M. (2010). MicroRNA expression profiles associated with phosphorus deficiency in white lupin (Lupinus albus L.). Plant Sci. 178 23–29. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.09.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuber H., Davidian J. C., Wirtz M., Hell R., Belghazi M., Thompson R., et al. (2010). Sultr4;1 mutant seeds of Arabidopsis have an enhanced sulphate content and modified proteome suggesting metabolic adaptations to altered sulphate compartmentalization. BMC Plant Biol. 10:e78 10.1186/1471-2229-10-78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]