Abstract

Neurodevelopmental biology, coupled with the application of advanced histological, imaging, molecular, cellular, biochemical, and genetic approaches, has provided new insights into these intricate genetic, cellular, and molecular events. During telencephalic development, specific neural progenitor cells (NPCs) proliferate, differentiate into numerous cell types, migrate to their apposite positions, and form an integrated circuitry. Critical disturbance to this dynamic process via genetic and environmental risk can cause neurological disorders and disability. The phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase (PI3K)-Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling cascade contributes to mediate various cellular processes, including cell proliferation and growth, and nutrient uptake. In light of its critical function, dysregulation of this node has been regarded as a root cause of several neurodevelopmental diseases, such as megalencephaly (“big brain”), microcephaly (“small brain”), autism spectrum disorders, intellectual disability, schizophrenia, and epilepsy. In this review, particular emphasis will be given to the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway and their paramount importance in neurodevelopment of the cerebral neocortex, because of its critical roles in complex cognition, emotional regulation, language, and behaviors.

Keywords: Brain development, PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway, Neurodevelopmental diseases, Megalencephaly, Microcephaly

Introduction

The mammalian neocortex is a complicated, tightly orchestrated, and six-layered construction that contains various neuronal subtypes and glias. The diverse neurons and glias of the central nervous system (CNS) are produced by a small, heterogeneous population of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) that undergo transcriptional changes to sequentially specific distinct cell fates, guided by temporal cell extrinsic and intrinsic cues. Astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (OLs), the major glial sub-lineages in the CNS, play key roles in telencephalic development and homeostatic maintenance with increasing brain complexity, controlling various aspects of neurodevelopment and diseases (Gallo & Deneen 2014; Zuchero & Barres 2015).

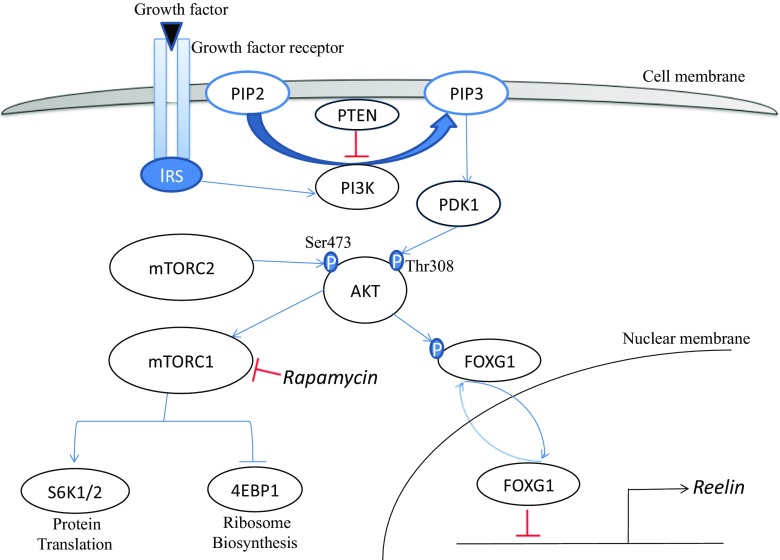

PI3K-Akt-mTOR cues regulate various cellular functions, including nutrient uptake, cell proliferation, growth, autophagy, apoptosis, and migration (Hennessy et al. 2005; Yu & Cui 2016). In the absence of extracellular stimulators, Akt is cytoplasmic and inactive (Alessi et al. 1996). Upon phosphor-activated by PI3K, Akt is recruited to the plasma membrane through binding of its pleckstrin homology (PH) domain to phosphatidylinositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3), which is produced by PI3K (Alessi et al. 1997). Translocation of Akt enables phosphorylation of Thr308 on its activation loop by membrane-localized phosphoinositide dependent kinase 1 (Pdk1) (Alessi et al. 1997; Stokoe et al. 1997). Full activation of Akt requires phosphorylation of Ser473, which lies in a C-terminal hydrophobic motif (HM) of Akt, by the rapamycin-insensitive mTORC2 (Sarbassov et al. 2005). Akt further stimulates mTORC1 through directly or indirectly suppression of TSC1/2 to abolish its inhibition of Rheb1, thereby stimulating mTORC1 (Laplante & Sabatini 2012). Another important negative regulator of the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway is Pten (phosphatase and tensin homolog). Through its lipid phosphatase activity, Pten dephosphorylates PIP3 to PIP2 and precisely counteracts the kinase function of PI3K and subsequent activation of downstream Akt-mTORC1 signaling (Song et al. 2012). The best-defined downstream targets of Akt-mTORC1 are the p70 ribosomal S6 protein kinases 1 and 2 (S6K1/2) (Fenton & Gout 2011) and the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding proteins (4E-BPs), which are in direct response to mTORC1 activation to initiate translation (Ma & Blenis 2009).

Dysfunction of PI3K-Akt-mTOR cascade has been recognized as the root cause of both neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric diseases with distinct clinical phenotypes, such as autism spectrum disorder, epilepsy, brain injury, and a spectrum of developing brain malformations (Crino 2016; Wang et al. 2015; Yang & Mo 2016; Yu et al. 2015). In this review, we discuss the functions of this pathway during embryonic forebrain development, with a particular focus on the putative molecular mechanisms underlying these functions (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Molecular mechanisms of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling cascade related neurodevelopmental diseases

Dysregulation of Akt3 Is Associated with Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Akt (also called protein kinase B or Pkb) is a member of the serine/threonine protein kinase AGC family and has three isoforms Akt1/Pkbα, Akt2/Pkbβ, and Akt3/Pkbγ. Akt, as a central node, is a positive regulator of several signaling pathways including cell proliferation, growth, survival, and metabolism across many species (Engelman et al. 2006; Hennessy et al. 2005; Hou & Klann 2004; Manning & Cantley 2007). Although the three Akt isoforms show high homology and share similar structures, mouse genetics have demonstrated that they play not only over-lapping but also specialized roles in development and physiology (Bae et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2010; Cho, Mu et al. 2001a; Cho, Thorvaldsen et al. 2001b; Yun et al. 2008).

Akt3 expression in the human fetal and mouse adult brain is higher than its expression in any other tissue sampled, whereas Akt1 and Akt2 show comparable to or lower levels of fetal brain expression than those seen in other tissues (Easton et al. 2005; Wu et al. 2009). Moreover, Akt3 is expressed at higher levels than Akt1 and Akt2 in the human fetal and mouse adult brain (Easton et al. 2005; Wu et al. 2009). Therefore, Akt3 was the predominant isoform and present in all areas of the adult mouse brain, representing about one half of the total Akt protein in adult brains (Easton et al. 2005; Wu et al. 2009).

Although specialized substrate and function of protein kinases might be attributed to their tissue-specific expression, the virtually ubiquitous localization of many critical kinases, including Akt, makes this an unlikely general mechanism. An appealing area of Akt studies is also to define their isoform-specific roles. Immunostaining using an antiserum that recognizes all three phospho-activated forms of Akt (p-Akt) exhibits widespread p-Akt localization in the developing cortex, with remarkable enrichment in neural progenitor cells in the ventricular zone, suggesting Akt’s primary role in brain development (Poduri et al. 2012). Further support for the distinct role of Akt3 in controlling brain size firstly comes from animal studies. Two independent mouse Akt3 knockout models show selective reduction in brain size (Easton et al. 2005; Tschopp et al. 2005), whereas mice with an activating mutation of Akt3 show enlarged brain size and increased corpus callosum thickness (Tokuda et al. 2011). Unlike the Akt3 isoform, mice lacking single Akt1 and Akt2 show smaller size of multiple organs and a diabetes-like syndrome, respectively (Cho et al. 2001a; Cho et al. 2001b). Deletions of chromosome 1q42-q44 (encompassing the AKT3 gene) in human genome have been reported in a variety of developmental aberrations of the brain, including agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC) and microcephaly. Several clinical studies demonstrate that haploinsufficiency of AKT3 in this region causes microcephaly and ACC (Boland et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2013). However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms of the disease and the strategy for therapies remain poorly defined.

Disturbances of cortical development at various critical stages—such as neural proliferation, migration, and orchestration—lead to representative malformations of cortical development (MCD) (D’Gama et al. 2015; Jansen et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2012; Riviere et al. 2012; Striano & Zara 2012). MCD are progressively recognized as a critical cause of neurodevelopmental delay, intellectual disability, ASD, and especially clinically intractable “catastrophic” epilepsy (Striano & Zara 2012). The most severe type of the spectrum is hemi-megalencephaly (HME), characterized by enlargement of most or all of one entire cerebral hemisphere, typically causing a medically severe pediatric epilepsy that requires surgical resection (Flores-Sarnat et al. 2003). Post-zygotic somatic activation of AKT3 is found in a wide range of brain diseases, including megalencephaly (“big brains”) and HME. De novo germline 1q43q44 (encompassing the AKT3 gene) trisomy has been reported in megalencephaly (Jansen et al. 2015). Somatic chromosome 1q43q44 (encompassing the AKT3 gene) tetrasomy and a gain of function mutation in AKT3 (c.49G/ A, creating p.E17K), have been reported in HME (Poduri et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2013). In contrast, most strikingly though, the somatic AKT3 mutation identified is highly paralogous to the common E17K mutations in AKT1 and AKT2, associated with Proteus syndrome, another multisystem overgrowth disorder, and hypoglycemia and left-sided overgrowth, respectively (Hussain et al. 2011; Lindhurst et al. 2011). Introducing the focal MCD-causing AKT3 E17K mutation into the mouse brain causes impaired hemispheric architecture and electrographic seizures (Baek et al. 2015). Mutant AKT3 E17K-expressing NPCs showed dysregulation of Reelin, which leads to a non-cell autonomous migration defect in neighboring cells, due at least in part to transcriptional de-repression of Reelin (Baek et al. 2015). The forkhead box (FOX) transcription factors has been established to function as transcriptional repressors, but after phosphorylation by AKT, FOXG1 translocates to the cytoplasm, thereby attenuating its transcriptional repression of Reelin (Brunet et al. 1999; Manning & Cantley 2007). Therapies aimed at either suppressing downstream AKT pathway by rapamycin or Reelin inactivation restored disrupted neuronal migration (Baek et al. 2015). These findings demonstrate a central AKT3-FOXG1-Reelin pathway in focal MCD, which also benefit to define how a mutation in just a few fraction of cells could perturb the gross organization of the entire hemisphere and elicit such devastating defects in brain development (Baek et al. 2015).

PI3K-AKT-mTOR Signaling in Neurodevelopment

A growing number of developmental brain malformations, characterized by altered cerebral architecture, abnormal neuronal morphology, and, often, intractable epilepsy, has recently been associated with novel mutations in genes encoding components of the Akt node (Striano & Zara 2012). Megalencephaly syndromes are probably genetically mosaic diseases caused by gain of function mutations in the PI3K–Akt3–mTOR pathway (D’Gama et al. 2015; Flores-Sarnat et al. 2003; Jansen et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2012; Riviere et al. 2012; Striano & Zara 2012). Recently, germline and somatic point mutations in AKT3, PIK3R2, and PIK3CA have been detected in the megalencephaly-related syndrome, and somatic gain of function point mutations in AKT3, PIK3CA, and MTOR has also been detected in HME, the most severe type of megalencephaly (Baek et al. 2015; Jansen et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2012; Nakamura et al. 2014; Poduri et al. 2012; Riviere et al. 2012). Sequencing at the single cell level identified a mutation burden in both neuronal and non-neuronal cells, denoting that mutations occur mainly in NPCs (Evrony et al. 2012; Poduri et al. 2013).

Conventional and conditional ablation of key components of the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway in mouse, such as Pten, Pdk1, Tsc1/2, mTOR, and Raptor (Costa-Mattioli & Monteggia 2013; Huber et al. 2015; Lipton & Sahin 2014; Zhou & Parada 2012), contributes to mechanistic researches and development of therapies for these devastating disorders. The brains deficient for Pdk1, Akt, mTOR, and Raptor all exhibit microcephaly (Costa-Mattioli & Monteggia 2013; Huber et al. 2015; Lipton & Sahin 2014; Zhou & Parada 2012). The disruption of mTOR resulted in aberrant cell cycle progression of NPCs in the developing forebrain and thereby disruption of progenitor self-renewal (Ka et al. 2014). Accordingly, genesis of intermediate progenitors and post-mitotic neurons were markedly prohibited (Ka et al. 2014). The brains deficient for raptor, essential for mTORC1 activity, exhibit a small brain starting at E17.5, which is the outcome of a decline in cell number and size (Cloetta et al. 2013).

Loss of Pten, leading to amplification of the AKT-mTOR signaling pathway, is a risk factor for macrocephaly, ASD, and glioma (Fraser et al. 2004; Li et al. 2002). Conditional elimination of Pten, causing hyperactivation of downstream Akt-mTOR pathway in the mouse CNS, has elucidated multiple roles in brain development and maintenance (Fraser et al. 2004; Groszer et al. 2001; Li et al. 2002; Marino et al. 2002; Yue et al. 2005). Pten deletion in NPCs resulted in its elevated proliferation and self-renewal in vitro and in vivo (Groszer et al. 2001), whereas Pten disruption in premature neurons caused hypertrophy without alteration on NPC proliferation (Fraser et al. 2004). Pten haploinsufficiency (Pten +/−) leads to a dynamic trajectory of brain overgrowth and altered scaling of neural cells, with an elevation of beta-catenin signaling (Chen et al. 2015). A heterozygous mutation in beta-catenin, itself a risk gene for microcephaly and ASD, inhibits cerebral overgrowth in Pten +/− mice, which provide a new perspective that Pten and beta-catenin signaling act in conjunction to control neural cell number and normal brain growth trajectory (Chen et al. 2015).

Together, the emerging consensus is that elevation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway leads to enhanced proliferation of progenitors, neuronal hypertrophy, and excessive dendritic branching, whereas suppression exhibits the opposite consequences (Costa-Mattioli & Monteggia 2013; Huber et al. 2015; Lipton & Sahin 2014; Zhou & Parada 2012).

Conclusions

Germline or widespread somatic mutations of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling networks may elicit overt brain architecture defects, whereas subtle, somatic, or cell type-specific mutations may lead to localized and restricted abnormalities. The severity and medical characteristics of neurodevelopmental diseases may be determined partially by the stage at which the mosaicism occurs relative to the distinct period of neurogenesis and gliogenesis, and which types of neural cells are affected. Therefore, more detailed researches are needed to decipher the cell type-specific effects of mosaic mutation and to determine which type of pathologies is attributed to specialized neural malfunction (Cai et al. 2014; Evrony et al. 2012; Poduri et al. 2013). Mouse models that manipulate the individual component of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway by genetic deletion in distinct neural cell types recapitulate the characteristic pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental diseases and contribute to define the underlying mechanisms and develop therapies for these catastrophic disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81370279 and 81370277). We appreciate it very much that Professor Guiquan Chen of Nanjing University has provided useful information and suggestion for this paper.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Alessi DR, Andjelkovic M, Caudwell B, Cron P, Morrice N, Cohen P, Hemmings BA. Mechanism of activation of protein kinase B by insulin and IGF-1. EMBO J. 1996;15:6541–6551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi DR, James SR, Downes CP, Holmes AB, Gaffney PR, Reese CB, Cohen P. Characterization of a 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase which phosphorylates and activates protein kinase Balpha. Current biology : CB. 1997;7:261–269. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(06)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae SS, Cho H, Mu J, Birnbaum MJ. Isoform-specific regulation of insulin-dependent glucose uptake by Akt/protein kinase B. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49530–49536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306782200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek ST, Copeland B, Yun EJ, Kwon SK, Guemez-Gamboa A, Schaffer AE, Kim S, Kang HC, Song S, Mathern GW, Gleeson JG (2015) An AKT3-FOXG1-reelin network underlies defective migration in human focal malformations of cortical development. Nature medicine [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Boland E, Clayton-Smith J, Woo VG, McKee S, Manson FD, Medne L, Zackai E, Swanson EA, Fitzpatrick D, Millen KJ, Sherr EH, Dobyns WB, Black GC. Mapping of deletion and translocation breakpoints in 1q44 implicates the serine/threonine kinase AKT3 in postnatal microcephaly and agenesis of the corpus callosum. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:292–303. doi: 10.1086/519999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, Anderson MJ, Arden KC, Blenis J, Greenberg ME. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a forkhead transcription factor. Cell. 1999;96:857–868. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Evrony GD, Lehmann HS, Elhosary PC, Mehta BK, Poduri A, Walsh CA. Single-cell, genome-wide sequencing identifies clonal somatic copy-number variation in the human brain. Cell Rep. 2014;8:1280–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Huang WC, Sejourne J, Clipperton-Allen AE, Page DT. Pten mutations alter brain growth trajectory and allocation of cell types through elevated beta-catenin signaling. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2015;35:10252–10267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5272-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Tang H, Hay N, Xu J, Ye RD. Akt isoforms differentially regulate neutrophil functions. Blood. 2010;115:4237–4246. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-255323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Mu J, Kim JK, Thorvaldsen JL, Chu Q, Crenshaw EB, 3rd, Kaestner KH, Bartolomei MS, Shulman GI, Birnbaum MJ. Insulin resistance and a diabetes mellitus-like syndrome in mice lacking the protein kinase Akt2 (PKB beta) Science. 2001;292:1728–1731. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5522.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Thorvaldsen JL, Chu Q, Feng F, Birnbaum MJ. Akt1/PKBalpha is required for normal growth but dispensable for maintenance of glucose homeostasis in mice. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38349–38352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100462200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloetta D, Thomanetz V, Baranek C, Lustenberger RM, Lin S, Oliveri F, Atanasoski S, Ruegg MA. Inactivation of mTORC1 in the developing brain causes microcephaly and affects gliogenesis. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:7799–7810. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3294-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Monteggia LM. mTOR complexes in neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1537–1543. doi: 10.1038/nn.3546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crino PB. The mTOR signalling cascade: paving new roads to cure neurological disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:379–392. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Gama AM, Geng Y, Couto JA, Martin B, Boyle EA, LaCoursiere CM, Hossain A, Hatem NE, Barry BJ, Kwiatkowski DJ, Vinters HV, Barkovich AJ, Shendure J, Mathern GW, Walsh CA, Poduri A. Mammalian target of rapamycin pathway mutations cause hemimegalencephaly and focal cortical dysplasia. Ann Neurol. 2015;77:720–725. doi: 10.1002/ana.24357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton RM, Cho H, Roovers K, Shineman DW, Mizrahi M, Forman MS, Lee VM, Szabolcs M, de Jong R, Oltersdorf T, Ludwig T, Efstratiadis A, Birnbaum MJ. Role for Akt3/protein kinase Bgamma in attainment of normal brain size. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1869–1878. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.5.1869-1878.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:606–619. doi: 10.1038/nrg1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evrony GD, Cai X, Lee E, Hills LB, Elhosary PC, Lehmann HS, Parker JJ, Atabay KD, Gilmore EC, Poduri A, Park PJ, Walsh CA. Single-neuron sequencing analysis of L1 retrotransposition and somatic mutation in the human brain. Cell. 2012;151:483–496. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton TR, Gout IT. Functions and regulation of the 70kDa ribosomal S6 kinases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Sarnat L, Sarnat HB, Davila-Gutierrez G, Alvarez A. Hemimegalencephaly: part 2. Neuropathology suggests a disorder of cellular lineage Journal of child neurology. 2003;18:776–785. doi: 10.1177/08830738030180111101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser MM, Zhu X, Kwon CH, Uhlmann EJ, Gutmann DH, Baker SJ. Pten loss causes hypertrophy and increased proliferation of astrocytes in vivo. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7773–7779. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo V, Deneen B. Glial development: the crossroads of regeneration and repair in the CNS. Neuron. 2014;83:283–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groszer M, Erickson R, Scripture-Adams DD, Lesche R, Trumpp A, Zack JA, Kornblum HI, Liu X, Wu H. Negative regulation of neural stem/progenitor cell proliferation by the Pten tumor suppressor gene in vivo. Science. 2001;294:2186–2189. doi: 10.1126/science.1065518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy BT, Smith DL, Ram PT, Lu Y, Mills GB. Exploiting the PI3K/AKT pathway for cancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:988–1004. doi: 10.1038/nrd1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou L, Klann E. Activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway is required for metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long-term depression. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24:6352–6361. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0995-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber KM, Klann E, Costa-Mattioli M, Zukin RS. Dysregulation of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in mouse models of autism. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2015;35:13836–13842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2656-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain K, Challis B, Rocha N, Payne F, Minic M, Thompson A, Daly A, Scott C, Harris J, Smillie BJ, Savage DB, Ramaswami U, De Lonlay P, O’Rahilly S, Barroso I, Semple RK. An activating mutation of AKT2 and human hypoglycemia. Science. 2011;334:474. doi: 10.1126/science.1210878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen LA, Mirzaa GM, Ishak GE, O’Roak BJ, Hiatt JB, Roden WH, Gunter SA, Christian SL, Collins S, Adams C, Riviere JB, St-Onge J, Ojemann JG, Shendure J, Hevner RF, Dobyns WB. PI3K/AKT pathway mutations cause a spectrum of brain malformations from megalencephaly to focal cortical dysplasia. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2015;138:1613–1628. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ka M, Condorelli G, Woodgett JR, Kim WY. mTOR regulates brain morphogenesis by mediating GSK3 signaling. Development. 2014;141:4076–4086. doi: 10.1242/dev.108282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Huynh M, Silhavy JL, Kim S, Dixon-Salazar T, Heiberg A, Scott E, Bafna V, Hill KJ, Collazo A, Funari V, Russ C, Gabriel SB, Mathern GW, Gleeson JG. De novo somatic mutations in components of the PI3K-AKT3-mTOR pathway cause hemimegalencephaly. Nat Genet. 2012;44:941–945. doi: 10.1038/ng.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Liu F, Salmonsen RA, Turner TK, Litofsky NS, Di Cristofano A, Pandolfi PP, Jones SN, Recht LD, Ross AH. PTEN in neural precursor cells: regulation of migration, apoptosis, and proliferation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20:21–29. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhurst MJ, Sapp JC, Teer JK, Johnston JJ, Finn EM, Peters K, Turner J, Cannons JL, Bick D, Blakemore L, Blumhorst C, Brockmann K, Calder P, Cherman N, Deardorff MA, Everman DB, Golas G, Greenstein RM, Kato BM, Keppler-Noreuil KM, et al. A mosaic activating mutation in AKT1 associated with the Proteus syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:611–619. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton JO, Sahin M. The neurology of mTOR. Neuron. 2014;84:275–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM, Blenis J. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:307–318. doi: 10.1038/nrm2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129:1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino S, Krimpenfort P, Leung C, van der Korput HA, Trapman J, Camenisch I, Berns A, Brandner S. PTEN is essential for cell migration but not for fate determination and tumourigenesis in the cerebellum. Development. 2002;129:3513–3522. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.14.3513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Kato M, Tohyama J, Shiohama T, Hayasaka K, Nishiyama K, Kodera H, Nakashima M, Tsurusaki Y, Miyake N, Matsumoto N, Saitsu H. AKT3 and PIK3R2 mutations in two patients with megalencephaly-related syndromes: MCAP and MPPH. Clin Genet. 2014;85:396–398. doi: 10.1111/cge.12188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poduri A, Evrony GD, Cai X, Elhosary PC, Beroukhim R, Lehtinen MK, Hills LB, Heinzen EL, Hill A, Hill RS, Barry BJ, Bourgeois BF, Riviello JJ, Barkovich AJ, Black PM, Ligon KL, Walsh CA. Somatic activation of AKT3 causes hemispheric developmental brain malformations. Neuron. 2012;74:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poduri A, Evrony GD, Cai X, Walsh CA. Somatic mutation, genomic variation, and neurological disease. Science. 2013;341:1237758. doi: 10.1126/science.1237758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riviere JB, Mirzaa GM, O’Roak BJ, Beddaoui M, Alcantara D, Conway RL, St-Onge J, Schwartzentruber JA, Gripp KW, Nikkel SM, Worthylake T, Sullivan CT, Ward TR, Butler HE, Kramer NA, Albrecht B, Armour CM, Armstrong L, Caluseriu O, Cytrynbaum C, et al. De novo germline and postzygotic mutations in AKT3, PIK3R2 and PIK3CA cause a spectrum of related megalencephaly syndromes. Nat Genet. 2012;44:934–940. doi: 10.1038/ng.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MS, Salmena L, Pandolfi PP. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrm3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokoe D, Stephens LR, Copeland T, Gaffney PR, Reese CB, Painter GF, Holmes AB, McCormick F, Hawkins PT. Dual role of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate in the activation of protein kinase B. Science. 1997;277:567–570. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5325.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striano P, Zara F. Genetics: mutations in mTOR pathway linked to megalencephaly syndromes. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:542–544. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuda S, Mahaffey CL, Monks B, Faulkner CR, Birnbaum MJ, Danzer SC, Frankel WN. A novel Akt3 mutation associated with enhanced kinase activity and seizure susceptibility in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:988–999. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschopp O, Yang ZZ, Brodbeck D, Dummler BA, Hemmings-Mieszczak M, Watanabe T, Michaelis T, Frahm J, Hemmings BA. Essential role of protein kinase B gamma (PKB gamma/Akt3) in postnatal brain development but not in glucose homeostasis. Development. 2005;132:2943–2954. doi: 10.1242/dev.01864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Cheng S, Yin Z, Xu C, Lu S, Hou J, Yu T, Zhu X, Zou X, Peng Y, Xu Y, Yang Z, Chen G. Conditional inactivation of Akt three isoforms causes tau hyperphosphorylation in the brain. Mol Neurodegener. 2015;10:33. doi: 10.1186/s13024-015-0030-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Zeesman S, Tarnopolsky MA, Nowaczyk MJ. Duplication of AKT3 as a cause of macrocephaly in duplication 1q43q44. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:2016–2019. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Orozco C, Boyer J, Leglise M, Goodale J, Batalov S, Hodge CL, Haase J, Janes J, Huss JW, 3rd, Su AI. BioGPS: an extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R130. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-11-r130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Mo X. An analysis of the effects and the molecular mechanism of deep hypothermic low flow on brain tissue in mice. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;22:76–83. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.15-00333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JS, Cui W. Proliferation, survival and metabolism: the role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling in pluripotency and cell fate determination. Development. 2016;143:3050–3060. doi: 10.1242/dev.137075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D, Fan C, Zhang W, Wen Z, Hu L, Yang L, Feng Y, Yin KJ, Mo X. Neuroprotective effect of nicorandil through inhibition of apoptosis by the PI3K/Akt1 pathway in a mouse model of deep hypothermic low flow. J Neurol Sci. 2015;357:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Q, Groszer M, Gil JS, Berk AJ, Messing A, Wu H, Liu X. PTEN deletion in Bergmann glia leads to premature differentiation and affects laminar organization. Development. 2005;132:3281–3291. doi: 10.1242/dev.01891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun SJ, Kim EK, Tucker DF, Kim CD, Birnbaum MJ, Bae SS. Isoform-specific regulation of adipocyte differentiation by Akt/protein kinase Balpha. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371:138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Parada LF. PTEN signaling in autism spectrum disorders. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22:873–879. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuchero JB, Barres BA. Glia in mammalian development and disease. Development. 2015;142:3805–3809. doi: 10.1242/dev.129304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]