Abstract

Conformational studies on the synthetic 11-aa peptide t-butoxycarbonyl (Boc)-Val-Ala-Phe-α-aminoisobutyric acid (Aib)-(R)-β3-homovaline (βVal)-(S)-β3-homophenylalanine (βPhe)-Aib-Val-Ala-Phe-Aib-methyl ester (OMe) (peptide 1; βVal and βPhe are β amino acids generated by homologation of the corresponding l-residues) establish that insertion of two consecutive β residues into a polypeptide helix can be accomplished without significant structural distortion. Crystal-structure analysis reveals a continuous helical conformation encompassing the segment of residues 2–10 of peptide 1. At the site of insertion of the ββ segment, helical hydrogen-bonded rings are expanded. A C15 hydrogen bond for the αββ segment and two C14 hydrogen bonds for the ααβ or βαα segments have been characterized. The following conformational angles were determined from the crystal structure for the β residues: βVal-5 (φ = –126°, θ = 76°, and ψ = –124) and βPhe-6 (φ =–88°, θ = 80°, and ψ =–118). The N terminus of the peptide is partially unfolded in crystals. The 500-MHz 1H-NMR studies establish a continuous helix over the entire length of the peptide in CDCl3 solution, as evidenced by diagnostic nuclear Overhauser effects. The presence of seven intramolecular hydrogen bonds is also established by using solvent dependence of NH chemical shifts.

Keywords: α/β-helix, C14 hydrogen bond, C15 hydrogen bond, αββ segment, ββα segment

The rapid advances made in elucidating the conformational properties of β amino acid residues (1–4) permit attempts to rationally design hybrid α/β peptides, in which guest residues can be incorporated into regular host secondary structures (5). The β residues have been incorporated into both the turn and strand positions of designed β-hairpin peptides. There are few examples of the insertion of β residues into well defined α-peptide helices. The only crystallographically characterized examples are the structures of 8- and 11-aa peptides, in which a βγ segment has been inserted into a peptide helix, with concomitant expansion of the hydrogen bonded rings at the site of insertion (6). Regular helical structures with mixed hydrogen bonds have been proposed from the NMR studies of alternating α/β sequences, containing the stereochemically restricted β residue trans-2-aminocyclopentanecarboxylic acid (ACPC) (7). As part of a program to insert segments containing multiple β residues into α-peptide helices, we obtained the 11-aa peptide t-butoxycarbonyl (Boc)-Val-Ala-Phe-aminoisobutyric acid (Aib)-(R)-β3-homovaline (βVal)-βPhe-Aib-Val-Ala-Phe-Aib-OMe 1. This sequence was based on the parent α peptide Boc-Val-Ala-Phe-Aib-Val-Ala-Phe-Aib-Val-Ala-Phe-Aib-OMe 2, which adopted a complete helical conformation in crystals (8). Peptide 1 differs from the parent all-α sequence in having the central Val-Ala-Phe-Aib segment replaced by a βVal-βPhe-Aib segment, which formally corresponds to replacing a segment of 12 backbone atoms by a unit containing 11 backbone atoms. In this article, we establish the continuous helical conformation of peptide 1 by incorporating the ββ segment into ring-expanded hydrogen-bonded turns in crystals and in solution.

Experimental Methods

Peptide 1 is a deletion product in the synthesis of the target sequence, the 12-aa peptide Boc-Val-Ala-Phe-Aib-βVal-βAla-βPhe-Aib-Val-Ala-Phe-Aib-methyl ester (OMe). This synthesis was approached by a conventional fragment-condensation strategy, with Boc and OMe groups for N- and C-terminal protection, respectively. The final coupling involved a [4 + 8] condensation. At the final step, the tetrapeptide acid (Boc-Val-Ala-Phe-Aib-OH) was coupled to the N-terminal deprotected octapeptide (H-βVal-βAla-βPhe-Aib-Val-Ala-Phe-Aib-OMe). The 8-aa peptide (Boc-βVal-βAla-βPhe-Aib-Val-Ala-Phe-Aib-OMe) was prepared by [2 + 6] condensation involving an N-terminal dipeptide Boc-βVal-βAla-OH. In the large-scale preparation of the dipeptide, the product (Boc-βVal-βAla-OH) was contaminated with Boc-βVal-OH, resulting in an intermediate, which contained the C-terminal 7-aa (Boc-βVal-βPhe-Aib-Val-Ala-Phe-Aib-OMe) and the 8-aa (Boc-βVal-βAla-βPhe-Aib-Val-Ala-Phe-Aib-OMe) peptides. Subsequent synthetic steps yielded the final product, which contained both the targeted 12-aa sequence and the deletion peptide 1, which were purified by medium-pressure liquid chromatography on a reverse-phase C18 (40- to 63-μm) column, followed by HPLC on a C18 (5- to 10-μm) column with methanol–water gradients. Boc-(R)-βVal-OH, the Boc-(S)-βAla-OH, and the Boc-(S)-βPhe-OH were synthesized by Arndt–Eistert homologation of Boc-(S)-Val-OH (note the formal change of configuration assignment upon homologation), Boc-(S)-Ala-OH, and Boc-(S)-Phe-OH, respectively. Peptide couplings were mediated by N,N′dicyclohexylcarbodiimide and 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (9). Peptide 1 was characterized by electrospray ionization MS, M + Na+ = 1,318.6, and complete analysis of the 500-MHz 1H-NMR spectrum. Single crystals that were suitable for x-ray diffraction were obtained by slow evaporation from acetonitrile.

X-Ray Diffraction. The 3D x-ray diffraction data were collected on a crystal of 0.78 × 0.45 × 0.30 mm with CuKα radiation on an automated four-circle diffractometer at –60°C. The θ–2θ scan technique was used to measure data up to 2θmax = 119°. Of 6,321 measured reflections, 5,307 were considered to be observed with |Fo| > 4σ (Fo). A resolution of 0.88 Å was obtained. The structure was solved by direct phase determination and refined by full-matrix least-squares refinement on F2 data (10). The hydrogen atoms were placed in idealized positions and allowed to ride on the C or N atom to which they were bonded. A cocrystallized CH3CN molecule, which occurs in a void between peptide molecules merely as a space filler, has large thermal parameters that indicate disorder. The final reliability factor was R1 = 6.9% for 5,307 observed data and 842 parameters. Crystal data were as follows: C68H101N11O14.C2H3N, formula weight 1,295.6 + 39, orthorhombic space group P212121, a = 14.565 (1) Å, b = 16.148 (1) Å, c = 32.252 (2) Å, V = 7,585.5 Å3, Z = 4, and Dcalc = 1.169 Mg/m3.

NMR Spectroscopy. All NMR studies were carried out on a DRX-500-MHz spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA) at a peptide concentration of ≈4.6 mM, and a probe temperature of 300 K. Resonance assignments were done by using total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) and rotating-frame Overhauser effect spectroscopy (ROESY) experiments. All 2D data were collected in phase-sensitive mode by using the time-proportional phase incrementation (TPPI) method. Sets of 1,024 and 450 data points were used in the t2 and t1 dimensions, respectively. For TOCSY and ROESY, 24 and 64 transients were collected, respectively. A spin lock time of 300 ms was used in obtaining ROESY spectra. Zero filling was done to yield finally a data set of 2 × 1 K. A shifted square sine-bell window was used before processing. The solvent exposure of NH groups in CDCl3 was determined by titration up to a DMSO concentration of 25% (vol/vol).

Results and Discussion

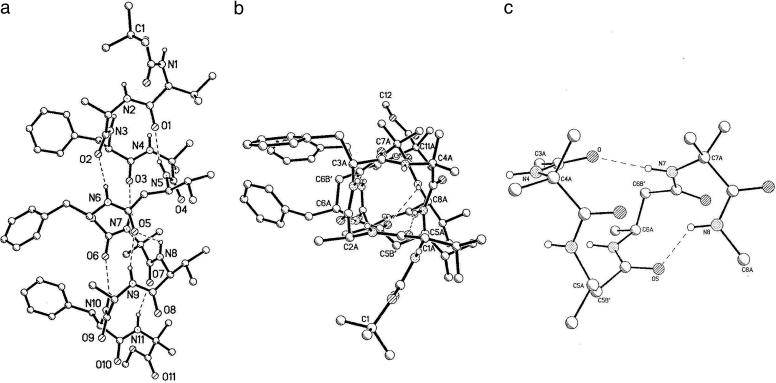

Fig. 1 shows the molecular conformation of peptide 1 in crystals. The backbone torsion angles for all of the α amino acid residues (Table 1) are in the range that is expected normally for right-handed α-helices. The terminal residues Val-1 and Aib-11 adopt left-handed (αL) conformations. The observation of the N terminus LVal residue in the αL region of conformational space is surprising, presumably a consequence of packing effects, which distorts the N terminus. Examples of partial unfolding of Aib residues at the N terminus in helical peptides have been reported (11). Chiral reversal of Aib residues at the C terminus of helical peptides is not unusual (12, 13).

Fig. 1.

X-ray structures. (a) Molecular conformation in crystals of the helical 11-aa peptide Boc-Val-Ala-Phe-Aib-βVal-βPhe-Aib-Val-Ala-Phe-Aib-OMe. (b) View into the helix showing the extended backbone at the N terminus. (c) An expanded view of Aib-βVal-βPhe-Aib segment, showing C11 and C15 hydrogen-bonded rings corresponding to an αββα segment.

Table 1. Torsion angles in peptide 1.

| Residue | φ, ° | θ, ° | ψ, ° | ω, ° | χ1, ° | χ2, ° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boc0 | 173 | -177 | ||||

| Val1 | 43 | — | 42 | -165 | -66, 60 | |

| Ala2 | -73 | — | -35 | 178 | ||

| Phe3 | -90 | — | -28 | 173 | -72 | 96, -80 |

| Aib4 | -60 | — | -47 | 172 | ||

| βVal5 | -126 | 76 | -124 | -169 | -49, -173 | |

| βPhe6 | -88 | 80 | -118 | -165 | -172 | -105, 74 |

| Aib7 | -55 | — | -49 | -178 | ||

| Val8 | -63 | — | -42 | -179 | -65, 169 | |

| Ala9 | -60 | — | -37 | 177 | ||

| Phe10 | -79 | — | -58 | -171 | -78 | 75, 103 |

| Aib11 | 42 | — | 49* | 178† |

Torsion around N11-C11A-C11′-O12.

Torsion around C11A-C11′-O12-C12.

The ββ segment is incorporated in the overall helical fold of the peptide with gauche conformations (θ ≈ 60°), being adopted at the residues βVal-5 and βPhe-6. Both β residues adopt φ,ψ values in the range of –88 to –126. These folds are close to the local conformations that are adopted by β residues in a right-handed 12-helix, (2.51-P-helix; nomenclature used by Seebach and Matthews, ref. 1).

The observed intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bond parameters are summarized in Table 2. Fig. 1c shows an expanded view of the peptide backbone in the vicinity of ββ segment to highlight the intramolecular hydrogen bond formation. Table 2 shows that the overall helical conformation is stabilized by seven potential intramolecular hydrogen-bond interactions. Of these possibilities, the following three correspond to conventional 5→1 C13 hydrogen bonds expected in an α-helical turn: Val-1 (CO) to βVal-5 (NH), βPhe-6 (CO) to Phe-10 (NH), and Aib-7 (CO) to Aib-11 (NH). These three C13 hydrogen bonds encompass ααα segments. Of the remaining four listed hydrogen bond interactions, two correspond to the C14 type, which is the expansion of a conventional C13 turn into a C14 turn by insertion of a β residue. The C14 hydrogen bonds encompass ααβ or βαα segments. The C15 hydrogen bond between Phe-3 (CO) and Aib-7 (NH) encompasses the central αββ segment. This helical turn is expanded by insertion of two additional backbone atoms into a conventional turn of α-helix. In addition, a bifurcated interaction involving βVal-5 (CO) with Val-8 (NH), corresponding to the C11 hydrogen bond encompassing the βα segment (βPhe-6–Aib-7), may be inferred. This hydrogen-bonding interaction corresponds formally to expansion of a 310 helical turn formed by an αα segment by replacement of an α amino acid by the corresponding β residue.

Table 2. Hydrogen bonds in peptide 1.

| Type (Cx) | Donor (NH) | Acceptor (CO) | N... O, A° | H... O, A° | C=O... N, ° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head-to-tail | N (1) | O (8) | 2.799 | 1.99 | 143 |

| Head-to-tail | N (2) | O (9) | 2.864 | 2.00 | 142 |

| Head-to-tail | N (3) | O (10) | 2.960 | 2.10 | 152 |

| Head-to-tail | N (4) | O (11) | 3.376* | 3.00* | |

| 5→1, (C13) | N (5) | O (1) | 3.005 | 2.17 | 158 |

| 5→1, (C14) | N (6) | O (2) | 2.801 | 1.91 | 144 |

| 5→1, (C15) | N (7) | O (3) | 2.887 | 2.01 | 158 |

| 4→1, (C11) | N (8) | O (5) | 3.044 | 2.57 | 137 |

| 5→1, (C14) | N (9) | O (5) | 2.985 | 2.14 | 161 |

| 5→1, (C13) | N (10) | O (6) | 3.137 | 2.29 | 169 |

| 5→1, (C13) | N (11) | O (7) | 2.932 | 2.06 | 162 |

Unfavorable values (see text).

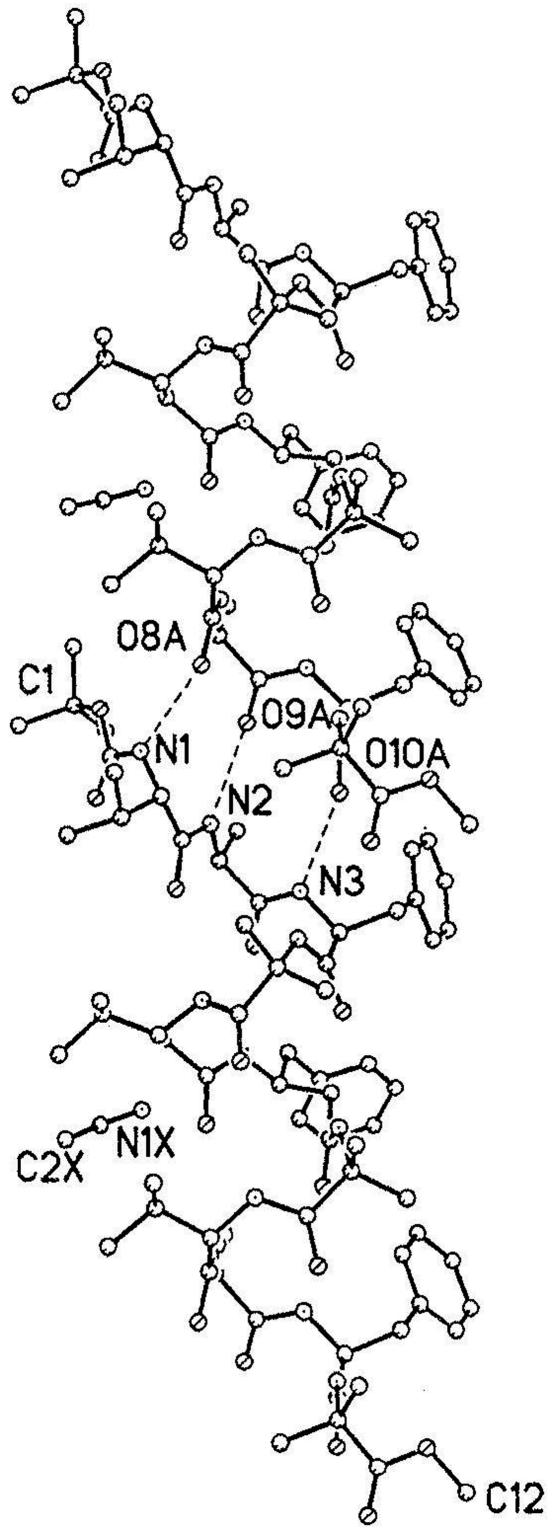

Packing in Crystals. Helices are packed by efficient intermolecular hydrogen bonds in a head-to-tail fashion (Fig. 2). The three NH groups at the N terminus (N1–N3) interact with three C-terminal CO groups (O8–O10) (Table 2). The unfolding of the helix at the N terminus by the adoption of an αL conformation at Val-1 results in the exposure of Aib-4 (NH) group. The N4... O11 distance of 3.376A° suggests a favorable interaction, but the orientation of the NH group (O.. .H-N = 3A°) does not favor a hydrogen bond. The CH3CN molecule fills vacant spaces between peptide molecules, with a closest approach of 3.58 Å to any C, N, or O atom.

Fig. 2.

The three O.. .HN bonds in the head-to-tail region that link the helices into infinite columns.

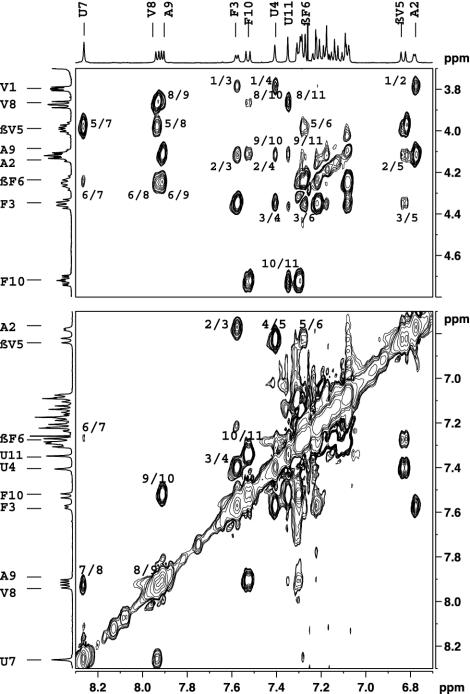

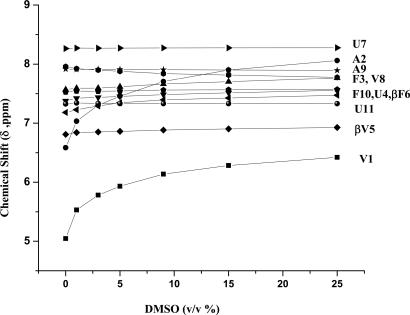

Solution Conformations. We carried out 500M-Hz 1H-NMR studies in CDCl3 and in a solvent mixture of CDCl3/DMSO (13%, vol/vol). Good chemical-shift dispersion permitted complete assignment of all backbone proton resonances. Fig. 3 shows partial ROESY spectra in which key nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs) are marked. Fig. 3 Lower shows sequential NH↔NH (dNN) connectivities, and Upper shows CαH↔NH (α residues) and CβH↔NH NOEs (β residues). The observed NOEs are completely consistent with the helical conformation determined in crystals. Fig. 4 summarizes the short intraproton distances in the ββ segment expected in the helical conformation established in crystals. For comparison, the corresponding distances in the extended sheet conformation of the ββ segments are shown. The number of intramolecular hydrogen bonds in peptide 1 in CDCl3 solution was determined in a solvent-perturbation experiment by monitoring the changes in amide proton chemical shifts upon the addition of the hydrogen-bonding solvent DMSO (Fig. 5). Only the two N-terminal amide protons of Val-1 and Ala-2 show more pronounced downfield shifts, with increasing concentrations of DMSO. The chemical shifts of all other NH groups are insensitive, confirming their shielding from the solvent and implicating them in intramolecular hydrogen bonding. These results support a continuous helical conformation encompassing the entire length of the peptide. This result in solution contrasts the crystal structure, in which the N terminus is partially unfolded, with Val-1 adopting positive φ,ψ values in the αL region, resulting in disruption of two potential intramolecular hydrogen bonds at the helix N terminus.

Fig. 3.

Partial 500-MHz ROESY spectrum of peptide 1 in CDCl3 at 300 K. (Upper) CαH↔NH NOEs (α residues) and CβH↔NH NOEs (β residues). (Lower) NH↔NH NOEs. Key NOEs are indicated.

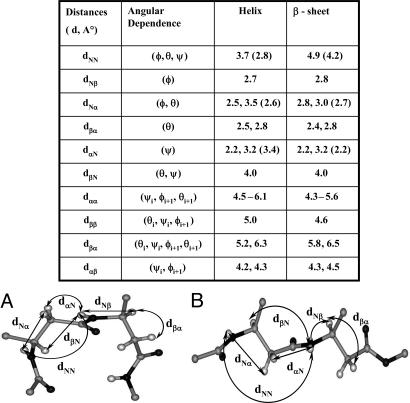

Fig. 4.

Interproton distances for a ββ segment present as a guest in a host α-peptide helix (A) and β-sheet conformation (B). Calculated distances are from the segments in crystal structures. The βVal-βPhe from peptide 1 (this study) (A) and βPhe-βPhe from peptide Boc-βPhe-βPhe dPro-Gly-βPhe-βPheOMe (B) (14). The subscripts indicate the atom type. Distances were crystallographically determined for β residues. The corresponding distances for α peptides are given in parenthesis. dαα distances are shown as ranges that represent the upper and lower limits.

Fig. 5.

Plot of solvent dependence of NH chemical shifts of peptide 1 at a varying concentration of (CD3)2SO in CDCl3.

The structure of peptide 1 provides an example in which two consecutive β amino acid residues have been incorporated into the overall helical fold of a host α-peptide sequence. The growing body of crystal structures of peptides containing β residues permits definition of the backbone conformational parameters characteristics of specific polypeptide folds involving these residues. In the early phase of research on β peptides, the observation of helices that were unprecedented in the extensive literature of α peptides seemed to be surprising. Seebach and Mathews (1) noted that “the expectation of many a colleague and protein specialist was that insertion of a CH2 group into each residue in a peptide backbone would lead to conformational chaos.” Clearly, this expectation has not been borne out by the subsequent body of work. In β residues, insertion of an additional saturated C atom into the polypeptide backbone adds an additional torsional variable. However, the values of the dihedral angle θ, corresponding to the torsional freedom about the Cα—Cβ bond, are limited to gauche (g+, g–) and trans (t) conformations. The accretion of substituents at the Cα and Cβ atoms limits the range of conformational choices further. The available structural evidence suggests that β residues can be accommodated comfortably in α-peptide helices if gauche conformations are adopted about Cα—Cβ bonds. In the case of β-sheets, the large number of available examples suggest that the trans conformation (θ = 180°) is favored strongly (14), although gauche conformations can be accommodated with some distortion of neighboring torsion angles, as exemplified by the structure of octapeptide Boc-Leu-Val-βVal-DPro–Gly-βLeu–Val-Val-OMe (9).

Acknowledgments

We thank Anindita Sengupta for help in generating some of the figures. This work was supported in Bangalore by a program support grant in the area of drug and molecular design by the Government of India Department of Biotechnology. R.S.R. is a recipient of a senior research fellowship from the Government of India Council of Scientific and Industrial Research. The work at the Naval Research Laboratory was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM30902 and the Office of Naval Research.

Abbreviations: Aib, aminoisobutyric acid; Boc, t-butoxycarbonyl; βVal, (R)-β3-homovaline; βPhe, (S)-β3-homophenylalanine; OMe, methyl ester; ROESY, rotating-frame Overhauser effect spectroscopy; NOE, nuclear Overhauser effect.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates, bond lengths, and angles have been deposited in the Cambridge Structural Database, Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, United Kingdom (CSD reference no. 247754).

References

- 1.Seebach, D. & Matthews, J. L. (1997) Chem. Commun., 2015–2022.

- 2.Cheng, R. P., Gellman, S. H. & DeGrado, W. F. (2001) Chem. Rev. (Washington, D.C.) 101, 3219–3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lelais, G. & Seebach, D. (2004) Biopolymers 76, 206–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruckner, A. M., Chakraborty, P., Gellman, S. H. & Diederichsen, U. (2003) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 4395–4399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roy, R. S. & Balaram, P. (2004) J. Peptide Res. 63, 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karle, I. L., Pramanik, A., Banerjee, A., Bhattacharjya, S. & Balaram, P. (1997) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 9087–9095. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayan, A., Schmitt, M. A., Ngassa, F. N., Thomasson, K. A. & Gellman, S. H. (2004) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 505–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aravinda, S., Shamala, N., Das, C., Sriranjini, A., Karle, I. L. & Balaram, P. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 5308–5315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gopi, H. N., Roy, R. S., Raghothama, S., Karle, I. L. & Balaram, P. (2002) Helv. Chim. Acta 85, 3313–3330. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheldrick, G. M. (1994) shelxtl(Bruker AXS, Madison, WI), Version 5.1.

- 11.Karle, I. L., Flippen-Anderson, J. L., Uma, K., Balaram, H & Balaram, P. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 765–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prasad, B. V. V. & Balaram, P. (1984) CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 16, 307–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karle, I. L. & Balaram, P. (1990) Biochemistry 29, 6747–6756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karle, I. L., Gopi, H. N. & Balaram, P. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 5160–5164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]