Abstract

Cdc25B is a phosphatase that catalyzes the dephosphorylation and activation of the cyclin-dependent kinases, thus driving cell cycle progression. We have identified two residues, R488 and Y497, located >20 Å from the active site, that mediate protein substrate recognition without affecting activity toward small-molecule substrates. Injection of Cdc25B wild-type but not the R488L or Y497A variants induces germinal vesicle breakdown and cyclin-dependent kinase activation in Xenopus oocytes. The conditional knockout of the cdc25 homolog (mih1) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae can be complemented by the wild type but not by the hot spot variants, indicating that protein substrate recognition by the Cdc25 phosphatases is an essential and evolutionarily conserved feature.

Keywords: protein–protein interactions

The hot spot theory of protein–protein interactions suggests that the binding energy between two proteins is governed in large part by just a few critical residues at the binding interface. In typical interfaces of 1,200–2,000 Å2, only ≈5% of the residues from each protein contribute >2 kcal/mol to the binding interaction (1). Although the establishment of the hot spot theory in pioneering studies by the Wells and Fersht laboratories using the high-affinity systems of human growth hormone binding protein (2) and barnase–barstar (3) has been subsequently validated in other similar systems, it is less clear to what extent hot spot theory applies to the transient protein–protein interactions involved in enzyme catalysis. Given that many such transient interactions govern crucial intracellular signaling processes (for example, protein kinases and phosphatases), it is of great interest to identify and characterize such potential hot spots. Identification of these hot spots would allow for experiments that probe the details of specific transient protein–protein interactions in vivo. Additionally, such sites could serve as targets for the development of small-molecule compounds that interfere specifically with these protein–protein interactions and serve as leads for drug development.

Cdc25 phosphatases are regulators of the eukaryotic cell cycle that dephosphorylate and thus activate the main gatekeepers of this process, the cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks/cyclins) (4). Confirming their importance in cell cycle regulation, Cdc25A and Cdc25B contribute to oncogenic transformation and are overexpressed in many diverse types of cancer (5). Crystal structures of the catalytic domains of Cdc25A and Cdc25B have revealed a shallow active site with no obvious features for mediating substrate recognition, suggesting a broad protein interface rather than a lock-and-key interaction (6, 7). This finding is confirmed by the activity of the Cdc25 phosphatases toward Cdk/cyclin protein substrates, which is six orders of magnitude greater than that of peptidic substrates that contain the same primary sequence (8). The shallow active site also correlates with the lack of potent and specific inhibitors of the Cdc25 phosphatases, despite extensive efforts to identify such inhibitors (9). The specificity of Cdc25 for its protein substrate appears to reside primarily in the catalytic domain, because full-length and catalytic domains are equally efficient at removing the first phosphate from the bis-phosphorylated substrate Cdk2-pTpY/CycA (8). The only part of the catalytic domain of Cdc25B known to be specifically involved in the interaction with the natural protein substrate is the C-terminal tail, which is not seen in the crystal structures of the catalytic domains and mediates only a factor of 10 in activity (10). Herein we identify and validate hot spot residues in the catalytic domain of Cdc25B that are located 20–30 Å away from the active site and are more significantly involved in the recognition of the Cdk/cyclin substrate. Because these residues are conserved across eukaryotes, we are able to demonstrate the in vivo relevance of these hot spots in Xenopus laevis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Materials and Methods

Mutagenesis and Protein Expression. Site-directed mutagenesis of Cdc25B was performed by using the QuikChange protocol from Stratagene and the primers listed in Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. The catalytic domain of Cdc25B was expressed as an untagged protein after isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside induction in Escherichia coli BL-21(DE-3) as previously described (11). Mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization, and electrospray mass spectrometry analysis of the purified proteins. Protein yields appeared to vary depending on the stability of the mutant, ranging from 2 mg/liter for wild type to 0.5 mg/liter for Y497A to 0.01 mg/liter for the R488L.

Enzymatic Assays. All phosphatase reactions were performed in a three-component buffer system (50 mM Tris/50 mM Bis-Tris/100 mM Na acetate, pH 6.5) containing 2 mM DTT at 25°C. Reactions using p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP), 3-O-methyl fluorescein phosphate (mFP), and α-naphthyl-phosphate (200–640 μM) were followed by continuous UV-Vis spectroscopy at 410 nm (ε = 5,142 M–1·cm–1 at pH 6.5), 477 nm (ε = 27,200 m–1·cm–1), and 324 nm (ε = 1,480 M–1·cm–1), respectively. All assays using pNPP and mFP consisted of complete Km determinations using seven concentrations of substrate between 0.2 and 5× Km and were fitted to Cleland's equations (12). Reactions with 200–640 μM α-naphthyl-phosphate were performed with 1–2 μM enzyme. The assays with natural substrate Cdk2-pTpY/CycA were performed as follows (see also ref. 8). Cdk2/CycA (200 μg) was phosphorylated by GST-tagged Myt1 (50 μg) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP (200–500 Ci/mol; 1 Ci = 37 GBq). After removal of the Myt1 by GSH-Sepharose and the unincorporated ATP by G-50 chromatography, the Cdk2-pTpY/CycA substrate could be assayed with Cdc25 by monitoring release of inorganic phosphate. Reactions initiated by enzyme in the presence of 1 mg/ml BSA and 0.05% Tween 20 were quenched by the addition of trichloroacetic acid to a 10% final concentration. After centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove the unreacted substrate, the supernatant was subjected to scintillation counting. Assays using Cdk2-pTpY/CycA for kcat/Km determinations were performed at 50–150 nM substrate. Time dependence (five points minimum), substrate concentration dependence (two to three differing concentrations), and enzyme concentration dependence (four to five differing concentrations) were tested to ensure kcat/Km conditions. Km determinations using Cdk2-pTpY/CycA were performed by using 3–300 nM enzyme and 20–1,000 nM substrate, limited by the amounts we were able to prepare. Although the enzyme amounts approach substrate concentrations for the mutants, Michaelis–Menten conditions were confirmed by varying the enzyme concentration.

Xenopus Oocytes. Stage-VI oocytes from X. laevis were prepared as described (13). Cdc25 (4 × 10 nl to a 1 μM final concentration) was injected, and after 2.5 h germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) was monitored by visual inspection under the microscope. For analysis of Cdc2/CycB activity by assay with histone substrate, two oocytes from each injection were harvested, lysed, and assayed as described previously (14). For analysis of Cdc25B protein by Western blotting, six oocytes were harvested and lysed, and Cdc25B protein was detected by using the Santa Cruz Biotechnology antibody to the C terminus.

Yeast Transformations. In S. cerevisiae, cdc25 is known as mih1, and although deletion of mih1 alone is not lethal, simultaneous deletion along with hsl7 yields a lethal phenotype. Thus, the yeast strain JMY1290 (hsl7Δ GAL-MIH1 leu2) (15) was transformed with an integrating plasmid containing myc-tagged wild-type mih1 or the R488L and Y497A equivalents (R334L and Y446A) under the control of its genomic promoter. Transformants were selected on galactose plates lacking leucine. The phenotype of multiple transformants containing the newly introduced mih1 was visualized by microscopy after transfer of the cells into dextrose-containing media for 24 h. The expression of MIH1 was confirmed by Western blotting by using the Myc antibody as described (16).

Results and Discussion

In choosing a tractable number of mutations from the many possible surface residues on Cdc25B, we initially chose to mutate 13 residues in three different categories (Fig. 1). The first group of mutated residues was clustered (7–12 Å) around the active site of Cdc25B, and these residues are likely to contribute to substrate binding based on proximity. We chose residues Ser-477, Glu-478, Tyr-528, and Asn-532, of which Tyr-528 is conserved in all known Cdc25s. Precedence for residues close to the active site contributing to protein substrate binding exists in the serine proteases, particularly in the S1 pocket that governs substrate selectivity (17). Also, in the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B, Tyr-46 (8.3 Å from the active-site cysteine) has been shown to govern recognition of a peptidic substrate by 780-fold in the kinetic parameter Km (18). The second group of Cdc25B mutations was made in a collection of arginine residues that potentially interact with a cluster of negatively charged residues on Cdk2 (Asp-38, Glu-40, and Glu-42). The residues of the “arginine highway” (Arg-482, Arg-485, Arg-488, Arg-490, and Arg-544) range from 11 to 22 Å from the active-site cysteine, and only Arg-488 is completely conserved. Such ionic patch interactions between arginines and aspartates have precedence in mediating the substrate specificity in the mitogen-activated protein kinase field (19–21). The third set of mutations was chosen based on the potential that these prominent surface residues could serve as “knobs” that fit into “holes” on the Cdk2/CycA substrate. Amino acids Gln-396, Glu-404, Tyr-497, and Glu-534 are all >20 Å from the active-site cysteine, with only Tyr-497 being completely conserved. Although such remote binding interactions (16–21 Å) have been observed crystallographically in the case of the kinase-associated phosphatase binding to its Cdk2 substrate, the functional significance of these interactions have not been probed further (22).

Fig. 1.

Surface of Cdc25B showing the mutations. The image was generated with visual molecular dynamics (28).

Because our goal was to identify mutations that affected only protein substrate binding without altering the actual chemistry at the active site, we first characterized each of the mutant Cdc25s using small-molecule substrates. Although a poor substrate, pNPP is a useful probe of the first half reaction, formation of the phosphoenzyme intermediate. To probe the second step of the reaction, the hydrolysis of the phosphoenzyme intermediate, we used the substrate mFP. Most of the mutations did not significantly affect activity (less than a factor of four), as measured by kcat or kcat/Km, with either of these small-molecule substrates (Fig. 2). Two mutants located relatively close to the active site did exhibit markedly reduced activity for all substrates (R482L and Y528A; factors of ≈10 and ≈80, respectively). Tyr-528 makes a hydrogen bond with Glu-474, a residue within the active-site loop, and we have shown that Arg-482 is important for binding of inhibitors that are competitive with small-molecule substrates (23). Thus Arg-482 and Tyr-528 are not specifically involved with protein substrate recognition and were not further characterized.

Fig. 2.

Activity of Cdc25B mutants with pNPP, mFP, and protein substrate. Kinetic data for mutants of Cdc25B are shown as kcat, kcat/Km, and Cdk2-pTpY/CycA substrate (kcat/Km) as normalized by activity with pNPP (kcat/Km).

Measurement of the activity of the remaining Cdc25B mutants using the bis-phosphorylated protein substrate Cdk2-pTpY/CycA revealed only two mutants with greatly reduced activity toward protein substrate that retained wild-type activity toward the small-molecule substrates (Fig. 2). These two residues, Arg-488 and Tyr-497, qualify as hot spot residues by reducing the kcat/Km for Cdk2-pTpY/CycA by factors of 600 and 250, respectively. As expected for substrate-binding mutants, the effect is at least partially expressed in a significantly higher Km for protein substrate (Fig. 3). The observation that activity with the small-molecule substrates pNPP and mFP remains unchanged argues against the notion that long-distance allosteric changes in the active site caused by these mutations are responsible for the altered Km. We also confirmed that there was no change in mechanism by using phospho-amino acid analysis to show that phospho-threonine was still removed before phospho-tyrosine (data not shown). Also, we confirmed that the activity with the small-molecule substrate α-naphthyl-phosphate was unaffected. The essentially identical kcat/Km measurements of 1.8 ± 0.1, 1.1 ± 0.2, and 1.5 ± 0.1 M–1·s–1 for wild type, R488L, and Y497A, respectively, again emphasize the restriction of the observed effect to native protein substrate.

Fig. 3.

Km determination of Cdk2-pTpY/CycA for Cdc25B. The wild-type protein (open squares) yielded a Km of 440 ± 80 nM, whereas both hot spot mutants, Y497A (open triangles) and R488L (filled circles), were linear up to the highest achievable concentration, as seen in Inset. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

We probed the role of residues near to Tyr-497, namely Tyr-382 and Asp-496. The Y382A and D496A mutants, unchanged for small-molecule substrates, showed only modest changes (less than a factor of five) in the protein substrate assays (Fig. 2). Also, as noted earlier, mutants of Arg-485 and Arg-490, residues near Arg-488, caused only modest effects (less than a factor of 20) on activity with protein substrate. Thus, Arg-488 and Tyr-497 are true hot spot residues that mediate substrate recognition, whereas other nearby residues do not contribute significantly to this process. Our results suggest that the hot spot theory of protein–protein interactions may also apply to the transient enzymatic recognition of the Cdk2-pTpY/CycA protein substrate by Cdc25B. Interestingly, our two hot spot residues follow the observed trend that shows an enrichment for tryptophan, arginine, and tyrosine residues among hot spots (1).

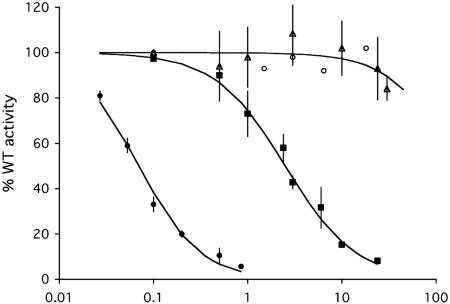

Cdc25B, like other members of the protein tyrosine family, can be converted to catalytically inactive substrate-trapping mutants by replacing the active-site Cys-473 with a serine (24). The C473S mutant binds tightly to Cdk2-pTpY/CycA and protects the substrate from dephosphorylation by wild-type enzyme at stoichiometric concentrations, indicating stable binding at less than submicromolar concentrations (Fig. 4). Mutating the active-site cysteine to aspartate (C473D) still allows the mutant enzyme to bind to protein substrate with reasonably high affinity (IC50 = ≈2 μM; see Fig. 4). The binding of C473D is presumably mediated not through binding at the active site but rather through remote sites, such as the hot spot residues. The extra atom of the aspartate residue compared with the wild-type cysteine or mutant serine protrudes sufficiently into the active-site pocket to prevent phosphate binding (G. Buhrman, C. Mattos, and J.R., unpublished observation). To probe the importance of the Tyr-497 hot spot residue in protein binding further, we generated the double mutants C473S/Y497A and C473D/Y497A. Neither of the double mutants protected Cdk2-pTpY/CycA from dephosphorylation by wild-type Cdc25B, indicating that binding was abrogated (Fig. 4). An estimate of the magnitude of the binding defect caused by the Y497A mutation can be obtained from the Y497A/C473D double mutation, where the apparent binding affinity is decreased by at least a factor of 60. The larger effect caused by the Y497A/C473S mutant (>1,500-fold) suggests an interesting and perhaps complex interplay between binding involving the hot spot residues and binding of phosphate in the active site. To ensure that this effect was not a result of misfolded protein, we examined them by CD spectroscopy. The wild-type, C473S, and C473D/Y497A proteins all showed essentially identical spectra with secondary structure predictions that matched data from the crystal structure (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The C473S/Y497A mutant had an altered but not unfolded profile. Similar experiments using double mutants of the active-site Cys-473 and the Arg-488 hot spot were not possible because these proteins were too unstable to be isolated. These data, along with our Km measurements, confirm that the hot spot mutations are critical for protein substrate binding.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition kinetics of catalytically inactive Cdc25B mutants. Activity of wild-type Cdc25B (3 nM) against Cdk2-pTpY/CycA (70 nM) was measured in the presence of varying concentrations (0.01–30 μM) of the catalytically inactive Cdc25B constructs [C473S (filled circles), C473D (filled squares), C473D-Y497A (open triangles), and C473S-Y497A (open circles)]. The percent activity observed at each given competitor concentration was fitted to percent activity = 100/(1 + [I]/IC50) where [I] is the concentration of inhibitor and IC50 values were calculated [C473S, 70 nM (apparent); C473D, 2.5 ± 0.5 μM; C473D/Y497A and C473S/Y497A, >150 μM). The data shown are mean values of at least three separate experiments.

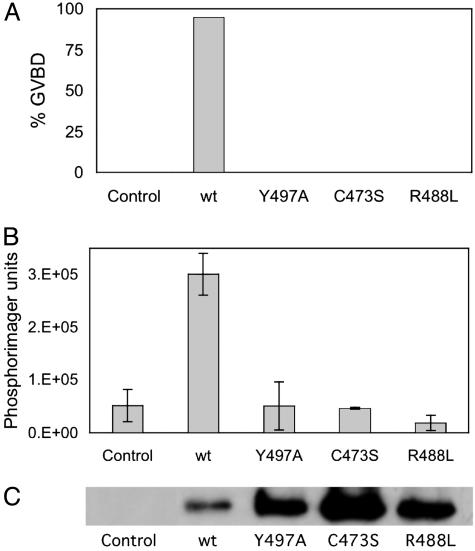

The conservation of Arg-488 and Tyr-497 in all known Cdc25s, from yeast to human, enabled us to address the physiological importance of these hot spot residues. The oocytes of X. laevis have long served as a model system for studying cell cycle events (25). Immature oocytes can be converted to fertilizable eggs by treatment with hormones such as progesterone. This oocyte maturation process, through the activation of various signal transduction pathways, converges to activate Cdc2/CycB, also known as the maturation-promoting factor. This incompletely understood signaling pathway can be circumvented by injection of exogenous Cdc25 from a variety of different species, leading directly to Cdc2/CycB activation and GVBD (26, 27) (Fig. 5). Injection of the Y497A or R488L mutants, like the active-site mutant C473S, did not cause GVBD or activation of histone kinase activity, even when the injected amount of the mutants exceeded wild type by a factor of 10. This finding suggests that the recognition site or sites for these hot spot residues on Cdc25 are conserved on the Cdc2/CycB complex in Xenopus.

Fig. 5.

Induction of GVBD and activation of Cdc2-histone kinase activity in Xenopus oocytes. (A) Cdc25 (1 μM final) was injected in stage-VI oocytes (14–18 replicates per enzyme form), and GVBD was monitored by visual inspection. (B) Histone kinase activity was tested from one to two pooled oocytes. (C) The presence of Cdc25B was demonstrated by Western blotting from six pooled oocytes.

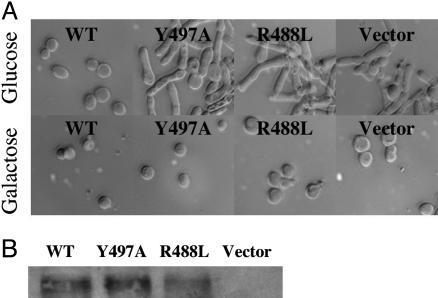

Mih1p (the Cdc25 homolog in S. cerevisiae) is not essential in budding yeast, but a conditional lethal phenotype occurs with a deletion of Hsl1p or Hsl7p (16). These two protein kinases are negative regulators of Swe1p (Wee1 in human), the kinase responsible for the inhibitory tyrosine phosphorylation of Cdk/cyclin that is the target of Mih1p (Cdc25). Deletion of these kinases leads to stabilized Swe1p and excessive kinase activity that results in a block in cell division in the absence of the phosphatase Mih1p (Cdc25). We took advantage of this phenotype to probe the importance of our hot spot residues at this extremum of the evolutionary scale. Incorporation of wild-type mih1 on an integrating plasmid rescues the hsl7Δ conditional mih1Δ phenotype, whereas neither of the hot spot mutants is able to complement the mutation (Fig. 6). It is important to note that these hot spot mutants in the yeast system work in the context of full-length protein and thus are not an artifact of working with the catalytic domain. Thus, protein substrate recognition by the Cdc25 phosphatases is an essential and evolutionarily conserved feature.

Fig. 6.

Hot spot mutants do not rescue conditional mih1 yeast deletion strain. Yeast strain JMY1290 (hsl7Δ GAL-MIH1 leu2) transformed with a vector containing myc-tagged mih1 wild type, R488L, Y497A, or empty vector control as grown in media containing glucose (Upper) or galactose (Lower). Note the elongated, nondividing phenotype in the strains that do not express functional Mih1 (Cdc25). (B) Western blot demonstrating expression of Mih1 by means of the C-terminal Myc tag in all but the control strain.

Physiologically, the hot spots Arg-488 and Tyr-497 that govern protein substrate recognition are as important to the reaction as the active-site cysteine that performs the nucleophilic attack. The sites of interaction on the Cdk/cyclin substrate remain to be determined, but based on these results it is expected that these residues will also be conserved. Also, more detailed kinetic investigations of possible kcat effects that accompany the pronounced change in Km need to be investigated to understand the detailed interplay between substrate recognition and catalytic activity. The elucidation of these details should provide further general insights into protein substrate recognition by protein phosphatases. Identification of these remote hot spot residues at the largest surface pocket on Cdc25 also opens the door for the design of novel inhibitors aimed at blocking this protein–protein interaction. Such inhibitors would be useful to probe the cell biology of Cdc25 and would serve as lead molecules for combating the many cancers that show overexpression of Cdc25.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sally Kornbluth and Daniel Lew and their laboratories (in the molecular pharmacology and cancer biology department of Duke University Medical Center) for generously providing Xenopus oocytes and the described yeast strains and vectors. We also thank George Dubay for help with electrospray mass spectrometry analysis. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM61822.

Author contributions: J.S., K.K., S.A., B.P., and B.K. performed research; J.S., K.K., and S.A. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; J.S. analyzed data; J.R. designed research; and J.R. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: pNPP, p-nitrophenyl phosphate; mFP, 3-O-methyl fluorescein phosphate; Cdk, cyclin-dependent kinase; GVBD, germinal vesicle breakdown.

References

- 1.Bogan, A. A. & Thorn, K. S. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 280, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clackson, T. & Wells, J. A. (1995) Science 267, 383–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schreiber, S. & Fersht, A. R. (1995) J. Mol. Biol. 248, 478–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nilsson, I. & Hoffmann, I. (2000) Prog. Cell Cycle Res. 4, 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kristjánsdóttir, K. & Rudolph, J. (2004) Chem. Biol. 11, 1043–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fauman, E. B., Cogswell, J. P., Lovejoy, B., Rocque, W. J., Holmes, W., Montana, V. G., Piwnica-Worms, H., Rink, M. J. & Saper, M. A. (1998) Cell 93, 617–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds, R. A., Yem, A. W., Wolfe, C. L., Deibel, M. R. J., Chidester, C. G. & Watenpaugh, K. D. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 293, 559–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudolph, J., Epstein, D. M., Parker, L. & Eckstein, J. (2001) Anal. Biochem. 289, 43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyon, M. A., Ducruet, A. P., Wipf, P. & Lazo, J. S. (2002) Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 1, 961–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilborn, M., Free, S., Ban, A. & Rudolph, J. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 14200–14206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, W., Wilborn, M. & Rudolph, J. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 10781–10789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleland, W. W. (1979) Methods Enzymol. 63, 103–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh, S., Margolis, S. S. & Kornbluth, S. (2003) Mol. Cancer Res. 1, 280–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang, J., Winkler, K., Yoshida, M. & Kornbluth, S. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 2174–2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theesfeld, C. L., Zyla, T. R., Bardes, E. S. G. & Lew, D. J. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 3280–3291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMillan, J. N., Longtine, M. S., Sia, R. A. L., Theesfeld, C. L., Bardes, E. S. G., Pringle, J. R. & Lew, D. J. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 6929–6939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedstrom, L. (2002) Chem. Rev. 102, 4501–4524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarmiento, M., Zhao, Y., Gordon, S. J. & Zhang, Z. Y. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 26368–26374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanoue, T., Adachi, M., Moriguchi, T. & Nishida, E. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanoue, T., Maeda, R., Adachi, M. & Nishida, E. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 466–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou, B., Wu, L., Shen, K., Zhang, J., Lawrence, D. S. & Zhang, Z. Y. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 6506–6515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song, H., Hanlon, N., Brown, N. R., Noble, M. E. M., Johnson, L. N. & Barford, D. (2001) Mol. Cell 7, 615–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sohn, J. & Rudolph, J. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 10060–10070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu, X. & Burke, S. P. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 5118–5124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrell, J. E. J. (1999) BioEssays 21, 833–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gautier, J., Solomon, M. J., Booher, R. N., Bazan, J. F. & Kirschner, M. W. (1991) Cell 67, 197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, M. S., Ogg, S., Xu, M., Parker, L. L., Donoghue, D. J., Maller, J. L. & Piwnica-Worms, H. (1992) Mol. Biol. Cell 3, 73–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. (1996) J. Mol. Graphics 14, 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.