In an active nerve terminal, exocytosis and endocytosis proceed at a frenzied pace. Each action potential releases ≈0.5% of the total supply of synaptic vesicles in the terminal (1), and, with some neurons firing at a rate of 50 Hz or greater, synapses would lose the ability to secrete neurotransmitter within seconds if they could not reform and refill synaptic vesicles. Endocytosis is the principal means, and perhaps the only means, by which the used vesicles are recovered and recycled into the releasable vesicle pool (2). Moreover, the rate of endocytosis is tightly coupled to the rate of exocytosis. In a resting terminal, endocytosis rates are low, but activity can increase this rate enormously to preserve the balance of exocytosis and endocytosis and thereby preserve the sizes of the nerve terminal and vesicle pool. How the rate of endocytosis is regulated, however, remains obscure. In this issue of PNAS, Nicholson-Tomishima and Ryan (3) report that synaptotagmin I, one of the principal proteins of the synaptic vesicle, has an important role to play in promoting the efficient endocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Synaptotagmin I has already been established as a significant contributor to exocytosis of synaptic vesicles (4). This protein is thus of consequence to both sides of the vesicle cycle at nerve endings. (Fig. 1).

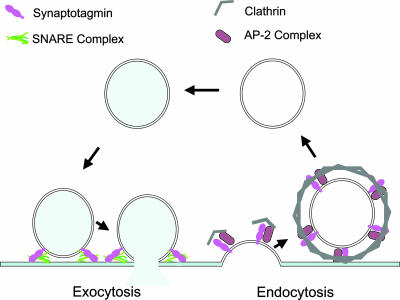

Fig. 1.

Synaptotagmin coming and going. Vesicles in the nerve terminal are recycled for repeated use. In promoting exocytosis, synaptotagmin interacts with membranes and the SNARE complex, the complex of syntaxin, SNAP-25, and synaptobrevin that likely mediate vesicle fusion. In promoting endocytosis, synaptotagmin interacts with the clathrin adaptor complex AP-2.

Measuring Endocytosis with Synapto-pHluorin

Precisely because of its involvement in exocytosis, synaptotagmin's involvement in endocytosis has long been suspected but difficult to establish. If endocytosis is decreased in a nerve terminal lacking synaptotagmin, is this due to a direct role of synaptotagmin in endocytosis or is it a consequence of a decrease in exocytosis, which indirectly reduces the rate of endocytosis? Nicholson-Tomishima and Ryan (3) have untangled the measurements of exocytotic and endocytic rates by using synapto-pHluorin (5), a pH-dependent fluorescent tag that was targeted to the inside of synaptic vesicles by being placed on the luminal domain of a synaptic vesicle protein (Fig. 2). Because synaptic vesicles are an acidic compartment, the synapto-pHluorin reporter does not fluoresce before exocytosis but does once exposed on the cell surface. After endocytosis, this fluorescence is rapidly quenched by the reacidification of the vesicle. Thus each exocytotic event increases the fluorescence of the nerve terminal and each endocytic event reduces it. The amount of fluorescence increase in the terminal after nerve stimulation represents the transient shift in vesicle proteins to the surface of the cell. But because exocytosis and endocytosis are occurring simultaneously, net fluorescence change represents a balance between the two processes and does not report the rate of either process alone. To determine these rates, Nicholson-Tomishima and Ryan apply an inhibitor of the vesicular proton pump, bafilomycin. Vesicles that undergo exocytosis now become persistently fluorescent: even after endocytosis, each vesicle that has been to the surface remains fluorescent because the newly internalized vesicles cannot be reacidified. Thus the increase in fluorescence in the nerve terminal in the presence of bafilomycin becomes a pure measure of the exocytotic rate. By determining the difference between this pure measure of exocytosis and the fluorescent change in the absence of bafilomycin (which measures exocytosis minus endocytosis), the endocytic rate was determined. In this manner, Nicholson-Tomishima and Ryan have compared exocytotic and endocytic rates in cortical cultures from WT and synaptotagmin I knockout mice. For comparable levels of exocytosis, the synapses lacking synaptotagmin were substantially slower to recover their vesicles.

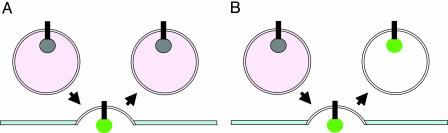

Fig. 2.

Synapto-pHluorins monitor the vesicle cycle. (A) The pH-dependent indicator fluoresces only when the vesicle is fused with the plasma membrane but not in the acidic compartments before and after. (B) In the presence of bafilomycin, the vesicles are not reacidified after endocytosis and the fluorescence persists.

Synaptotagmin I is of consequence to both sides of the vesicle cycle.

This evidence that synaptotagmin is necessary for rapid endocytosis of synaptic vesicles fits nicely with another recent study (6) in which a different approach was taken to test the involvement of synaptotagmin in endocytosis at the fly neuromuscular junction. Poskanzer et al. (6) also used synapto-pHluorin as a reporter of exocytosis and endocytosis. However, to separate direct actions on endocytosis from indirect consequences of altered exocytosis, they inactivated synaptotagmin after a stimulus train had induced exocytosis but before the terminal had completed the removal of the membrane from the surface. This precisely timed inactivation was accomplished by tagging synaptotagmin with fluorescein so that a laser flash would acutely produce free radicals and damage the adjacent protein. After the laser flash, the investigators measured the rate at which the fluorescence (representing the exocytosed vesicles) recovered back to prestimulus levels. Like Nicholson-Tomishima and Ryan (3), Poskanzer et al. found that the rate of endocytosis was slower with synaptotagmin inactivated. These studies took exceptionally divergent approaches: one study was conducted in cultures of mouse cortical neurons and the other at Drosophila neuromuscular junctions; one looked at a mutant lacking synaptotagmin and the other used fluorescence inactivation of synaptotagmin; and one looked at endocytosis both during and after the stimulation of the neuron and the other looked only at the phase of endocytosis that occurs after exocytosis. Their conclusions, however, were quite parallel and support an evolutionarily conserved and direct role of synaptotagmin in accelerating endocytosis.

Synaptotagmin Binding to AP-2 Likely Promotes Endocytosis

These studies mesh well with earlier work. In particular, synaptotagmin has been shown to bind the clathrin–adaptor complex AP-2 (7, 8). The binding of this complex is a mechanism by which domains of plasma membrane recruit clathrin and cargo proteins and thereby begin membrane invagination (9). The site of the interaction has been mapped to the C2B domain of synaptotagmin, and this interaction can enhance the recruitment of both the AP-2 complex and clathrin to liposomes (8). The AP-2 complex, however, also binds to inositol phospholipids on the membrane, and thus synaptotagmin was not expected to be a requisite step for AP-2 recruitment to the membrane. Rather, synaptotagmin may assist in concentrating the clathrin apparatus at sites of recycling vesicles or may help AP-2 to gather synaptic vesicle proteins. This model is consistent with the present study, which found that endocytosis persisted in mice lacking synaptotagmin I but was kinetically slower.

Synaptotagmin function in endocytosis does not diminish the case for it in exocytosis.

The evidence for synaptotagmin function in endocytosis does not diminish the case for synaptotagmin in exocytosis. Synaptotagmins remain leading candidates for the Ca2+ sensors that detect the transient increase in cytosolic Ca2+ that accompanies an action potential and, in response, promotes exocytosis of synaptic vesicles (4). This role is likely to be accomplished through the interaction of synaptotagmin with phospholipids and the proteins of the SNARE complex, the complex of plasma membrane and vesicle proteins that is critical for membrane fusion. Nicholson-Tomishima and Ryan (3), however, confirm another recent development for synaptotagmin I, the founding member of this family: mice lacking this protein release more neurotransmitter than was previously thought to be the case. The most salient feature of the phenotype is that the exocytosis of neurotransmitter is no longer extremely rapid and synchronized to a narrow window after the arrival of the action potential (10). Instead, transmitter is released in a more gradual manner due to the asynchronous fusion of synaptic vesicles. The net amount of transmitter released, particularly in response to trains of action potentials, may be very close to that seen in WT. This asynchronous release is also Ca2+-dependent and thus a Ca2+-sensing mechanism must persist in the absence of synaptotagmin I, as has been seen previously (11, 12). Thus, in both endocytosis and exocytosis, synaptotagmin I appears to increase the rate of the vesicle cycle but is not absolutely required. Interestingly, in both exocytosis and endocytosis, the C2B domain, which has both a Ca2+-binding site and an AP-2 binding site, appears to be crucial (13, 14).

How then does the nerve terminal change the rate of endocytosis in response to increased activity? The known binding of synaptotagmin to AP-2 and the demonstration that synaptotagmin is needed for efficient compensatory endocytosis suggest a likely model. Increased exocytosis would increase the amount of synaptotagmin on the surface of the terminal and this in turn would increase the rate at which AP-2 and clathrin were recruited for endocytosis. At least at some synapses, Ca2+ has a direct modulatory effect on endocytic rates (15, 16). There is also, therefore, the attractive possibility that the Ca2+-binding sites of synaptotagmin provide a further regulatory level in which the elevated Ca2+ that accompanies synaptic activity modulates the ability of synaptotagmin to promote endocytosis.

Synaptotagmin is now on record as participating in both sides of the synaptic vesicle cycle. Although some may think this reflects a functional flip-flop, the two roles likely work together for the efficient use and reuse of synaptic vesicles. Nicholson-Tomishima and Ryan (3) have thereby provided us with a more nuanced understanding of the regulation of the nerve terminal.

See companion article on page 16648.

References

- 1.Ryan, T. A. & Smith, S. J. (1995) Neuron 14, 983–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarousse, N. & Kelly, R. B. (2001) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 461–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholson-Tomishima, K. & Ryan, T. A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 16648–16652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sudhof, T. C. & Rizo, J. (1996) Neuron 17, 379–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miesenbock, G., De Angelis, D. A. & Rothman, J. E. (1998) Nature 394, 192–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poskanzer, K. E., Marek, K. W., Sweeney, S. T. & Davis, G. W. (2003) Nature 426, 559–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang, J. Z., Davletov, B. A., Sudhof, T. C. & Anderson, R. G. (1994) Cell 78, 751–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haucke, V., Wenk, M. R., Chapman, E. R., Farsad, K. & De Camilli, P. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 6011–6019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Traub, L. M. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 163, 203–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishiki, T. & Augustine, G. J. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 6127–6132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiAntonio, A., Parfitt, K. D. & Schwarz, T. L. (1993) Cell 73, 1281–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geppert, M., Goda, Y., Hammer, R. E., Li, C., Rosahl, T. W., Stevens, C. F. & Sudhof, T. C. (1994) Cell 79, 717–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackler, J. M., Drummond, J. A., Loewen, C. A., Robinson, I. M. & Reist, N. E. (2002) Nature 418, 340–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishiki, T. & Augustine, G. J. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 8542–8550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neves, G., Gomis, A. & Lagnado, L. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 15282–15287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sankaranarayanan, S. & Ryan, T. A. (2001) Nat. Neurosci. 4, 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]