Abstract

Since 1957, there has been major reorganization of health care services in Malaysia. This article assesses the changes and challenges in health care delivery in Malaysia and how the management in health care processes has evolved over the years including equitable health care and health care financing. The health care service in Malaysia is changing towards wellness service as opposed to illness service. The Malaysian Ministry of Health (MOH), being the main provider of health services, may need to manage and mobilize better health care services by providing better health care financing mechanisms. It is recommended that partnership between public and private sectors with the extension of traditional medicine complementing western medicine in medical therapy continues in the delivery of health care.

Key words: health care services, changes, challenges, social equity, and health care financing.

Health care system in Malaysia

Human capital and health improvement programmes are of central importance towards sustainable development and economic growth in any country.1 In Malaysia, the health care system has changed from traditional remedies to meeting the emerging needs of the population. Since the Independence of Malaysia in 1957, there has been major reorganization of health care services in the country.2 The first reorganization started at the public primary health care services and accelerated since the Alma Ata Declaration in 1978. In Malaysia, the Ministry of Health (MOH) is the main provider of health care services to the public. The organizational structure of the MOH has three levels, Federal, State and District, which are decentralized to ensure efficiency. Each hierarchical level determines the level of authority, information flow, accountability and supervision. This system encompasses all aspects of care such as preventive, promotive, curative and rehabilitative.3 The main objective is to provide a greater network of physical facilities, equity, accessibility and utilization of health care resources. At the same time, National Referral Centres were established to provide specialized care to enhance the basic care provided in health clinics.3

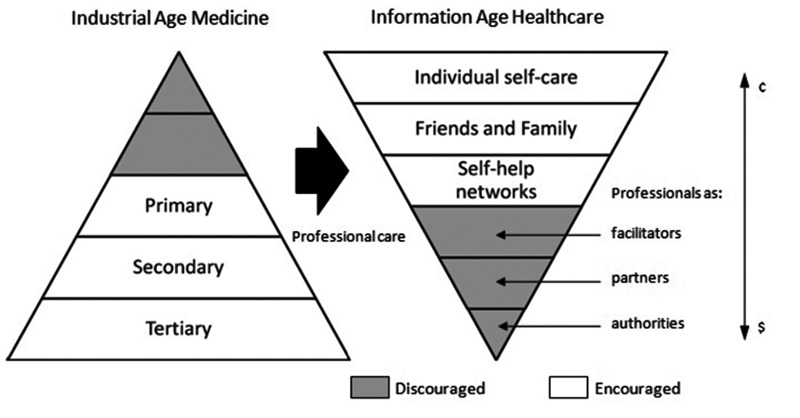

Over the past decade there has been an explosion of tertiary level specialized care to meet the needs of the population. Tertiary care focuses on the curative model, which is doctor and illness focused. This is expensive, fragmented and institutionally focused and inappropriate for the majority of health consumers.4 In the current era, health care is changing towards wellness services as opposed to illness services.4 This service includes a lifetime health plan that focuses on keeping the child and family well. This gives greater prominence to preventive issues and takes on healthier lifestyles by choices with risk prevention. The health care providers also need not function as controllers but act as facilitators or partners with health consumers4 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Transformation from industrial age medicine to information age health care (Source: Amar4).

Apart from the size of the hospitals, there are differences in terms of the services provided. Small district hospitals provide general medical and nursing care and their manpower consist of medical officers and other personnel. Larger district hospitals and regional hospitals provide a wide range of specialist services and the public has easy access through a walk-in or referral system.3 MOH seeks to ensure the public is informed of health issues and has access to safe water, safe food and quality medicine. The Malaysian health care system focuses on Primary Health Care (PHC) that places social equity as important and allocates public funds for the poorest 20% of the population.5 In 1956, there were only 42 PHC facilities in the country.5 After independence, the health sector became an integral part of the national and development process and MOH has been able to deliver health care to communities throughout the country.6 Table 1 shows increasing health care facilities in secondary and tertiary care over the years.

Table 1. Health facilities of the Ministry of Health, Malaysia in 1984, 2001 and 2008.

| MOH's facilities | 1984 | 2001 | 2008° |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health clinics | 361 | 843 | 802 |

| Rural/community clinics | 1039 | 1924 | 1927 |

| Mobile teams | 35 | 204 | 193 |

| Hospitals | 89 (21,159 beds) | 115 (29,123 beds) | 130 (33,004 beds) |

| Medical institutions | 8 (10,235 beds) | 6 (5551 beds) | 6 (5000 beds) |

Source: Adapted from Merican and bin Yon2;

Planning and Development Division, Ministry of Health, Malaysia.12

The number of hospitals, community clinics and other facilities such as Special Medical Institutions (National Heart Institute, Institute of Pediatrics and Institute of Respiratory Medicine) has increased (Table 2). The total expenditure from the Health Department of Selangor in 2006, for instance, has increased to RM 881.3 million compared to RM 628.83 million in 2005 and RM 577.77 million in 2004. The increase is due to new hospitals and comprehensive health services that are provided by the government.7 The Second National Health and Morbidity Survey in 1996 reported that 88.5% of the population stays within 5 km of a health facility and 81% lived within 3 km.5 Findings also show that basic health care and facilities are accessible to about 70% of the population in Sabah and Sarawak and more than 95% of the population in Peninsular Malaysia.8 These estimates do not include other types of outreach services such as flying doctors, mobile health teams, dental clinics, travelling dispensaries and riverine services.2,3

Table 2. Health care facilities in Malaysia 2009.

| Government | No. | Beds (official) |

|---|---|---|

| Ministry of health | ||

| Hospitals | 130 | 33,083 |

| Special medical institutions | 6 | 4974 |

| Special institutions* | 6 | - |

| National institutes of health | 6 | - |

| Dental clinics | 1724 | 2952° |

| Mobile dental clinics and teams | 560 | 1392° |

| Health clinics | 808 | |

| Community clinics (Klinik Desa) | 1920 | |

| Maternal & Child health clinics | 90 | |

| Mobile health clinics | 196 | |

| Non ministry of health | ||

| Hospitals | 8 | 3523 |

| Private | No. | Beds (official) |

|---|---|---|

| Licensed | ||

| Hospitals | 209 | 12,216 |

| Maternity homes | 21 | 102 |

| Nursing homes | 12 | 273 |

| Hospice | 3 | 28 |

| Ambulatory care centre | 21 | 108 |

| Blood bank | 5# | - |

| Haemodialysis centre | 75 | 848§ |

| Community mental health centre | 1 | 9 |

| Registered | ||

| Medical clinics | 6307 | - |

| Dental clinics | 1484 | - |

National Blood Centre, National Public Health Laboratory and 4 Regional Laboratories;

dental chairs;

refers to 4 Cord Blood Stem Cells Banks and 1 Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Research Lab and Services;

refers to dialysis chairs. Source: Planning and Development Division, Ministry of Health, Malaysia.13

There are other government agencies that complement the role of MOH to preserve the health of the people. For instance, the Ministry of Human Resources that enforces safety and health regulations of employees, Ministry of Education that is responsible for the operation of the teaching hospitals and training of health personnel of the country, Ministry of Defence that provides health services for its population within the territory, Ministry of Rural Development that is responsible for the health of the aborigines and Ministry of Housing and Local Government that is responsible for some of the licensing and enforcement under its purview.2,9

Studies have also shown that the Malaysian health standard is almost at par with those of developed countries.6,10 Data from the World Health Report in 1999 indicated that the health indicators of Malaysians were much better compared to some of the ASEAN countries. For example, the Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) in Malaysia is 11 per 1000 live births while in Indonesia it is 48 per 1000 live births and in Thailand it is 29 per 1000 live births. This figure is still high compared to the IMR of Singapore (5/1000 live births), United Kingdom (7/1000 live births) and America (7/1000 live births).2

Changes and challenges

Equitable health care

Equity is an assessment of fairness.1 Despite Malaysia's effort in socio-economic development plans, there still exist issues in equity and accessibility especially for the indigenous groups, rural population and the hard-core poor.5 This can be seen through quality in terms of health services, manpower and equity in terms of geographical location and accessibility in terms of price and tariff.11 The Asian economic crisis in 1998 has increased 50% of the poverty level in several countries which added difficulty for the poor and middle class in accessing health care. Nevertheless, efforts are taken by the government to strengthen the rural health services in Malaysia through the improvement of existing facilities and introducing new health services that range from outpatient curative care to preventive and promotive services.3 The rural health units consist of one health centre, four rural health units and mobile clinics. The rural health unit follows a two-tier system that provides subsidized or free health services to 15,000 to 20,000 rural population.2,3

There is a remarkable difference in the doctor-patient ratio in the country. There are 500 people per doctor in Kuala Lumpur and 4000 per doctor in Terengganu and East Malaysia.3 This ratio has been reduced over the years. As in 2009, the ratio of doctors to patients in Malaysia is 1:927 compared to 1:1105 in 2008.12,13

The Malaysian health care system is primarily divided into private and public sectors. One of the pending concerns of the government is that there are high concentrations of private practices in the urban areas due to the demand by the affluent community. In 1993, there are 3055 general practitioners clinics and 190 private hospitals and nursing homes in Malaysia.2 In 2000, 46.2% of all doctors were in the private sector and were accountable for only 20.3% of hospital beds while the rest of the 53.8% of doctors were in the public sector looking after 79.7% of the beds.2 It is reported that 58.8% of the specialists were in the private sector and about 41.2% were in the public sector.2 The findings through interviews from key personnel from MOH states that the charges from private hospitals on services component range from 15% to 28% of the hospital bills and medication whereby 15% of this bill is not made known to patients.6 Furthermore, professional fees take up almost 50% of the total bill.6 The difference in the public and private sectors in terms of specific services provided may have a significant effect on the equity of services and the question of efficiency and effectiveness.14 This leads to an imbalance of the distribution of manpower in public and private sectors in Malaysia.15

Generally, the services provided by private hospitals are curative and selective in nature, either free or subsidized and much more comprehensive which is controlled by issues of equity. Access to private health services is limited to the richer society that can afford out-of-pocket payments of higher fees.1 Immigrant health is another concern in Malaysia whereby 5% of the Malaysian population, which consists of about one million people, are immigrant workers.2 These foreign workers may harbour communicable diseases which originate from their country and this incurs health care cost when they use the health facilities in Malaysia.2 Moreover, there are many cases whereby foreign workers who have been admitted have defaulted in settling their bills and collectively with a number of other reasons unsettled hospital bills in public sectors are increasing.16 To address these issues, more comprehensive preventive measures and plans must be taken by designing and implementing conducive national health care financing scheme under the National Health Financing Authority (NHFA) within the realm of MOH.16

Health needs and challenges have changed over the past decade. Professionals in health care and the health care systems have changed at a much slower pace and are not usually suitable for the present health needs of the population.4 Throughout the world there seems to be fundamental changes in medical care delivery systems that is in progress. Asia Pacific region is the most varied health region in the world because it contains the country with the largest population in the world.15 However, it also includes countries that are fighting with epidemic obesity.15 This includes Malaysia which has about 8.3% of the population above 30 years suffering from diabetes and 29.9% from hypertension.17 In the less-developed countries in the region, women suffer from malnutrition, high mortality and morbidity.18

A large percentage of the population is moving through the economic transition and about 70% of the deaths are due to chronic diseases.15 The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) has published projections for changes in populations over the next 50 years. For population over 60 years, Malaysia will have an increase from 5.7% in 1996 to 11% by 2020.19

The World Health Organization (WHO) and individual countries are taking control of the progress by PHC. Although the definition of PHC varies from country to country, it cannot be denied that accessibility, quality of basic health care and equity within countries have improved.19 Nevertheless, the populations most in need are the aborigines, the poor, the disadvantaged and the disabled.4,18 These groups have the least access to health services according to the inverse care law4 which explains that health care tend to operate based on active market forces.20 However, meeting their needs will be very challenging,21 because every individual has a right to health care services and it is essentially the responsibility of the government to ensure this access.22

Health care financing

Health care financing is a key concern all over the world today. Among others, some of the sources of funding health care are through taxation, social and private health insurance and out-of-pocket payments.1 The Malaysian government finances the public health services through the Consolidated Revenue Fund under the Ministry of Finance while the sources from the private sector are essentially from the consumers.16 The system of financing is inclined towards the public sector whereby only a nominal fee of RM1 for each outpatient visit is charged16 in accordance to the Fees (Medical) Order 1976.1 Government employees and their family members benefit from these services even after their retirement while the Social Security Organization (SOCSO) and Employees Provident Fund (EPF) do not finance employees in the private sector during their retirement.16 Comparatively, the British government initiated the 1912 National Health Insurance policy to compensate salaries of workers who have lost their jobs due to sickness.23 Commercialization of health care is not financially viable for the majority of the consumers and is inappropriate because any framework of health care provision must be in line with the needs of the consumers.4 As a result, it has undermined the trust of individuals to the health care profession and the government.4

Health care financing is a main challenge in many countries and should be taken into consideration in providing a safety net for the poor.19 The United States spends 14% of its GNP compared to Asian countries that spends about 4–8% of their GNP on health care.24 With new technologies, capitalization of expensive hospital facilities and specialization has increased the cost of medical services. In 2001, returns collected by MOH Malaysia in providing medical, health and dental care services amounted to 2.2% of the total operating budget.2,3

The Medical Price Index in Malaysia has increased more than the Consumer Price Index.14 In some parts of the countries, where the force of the financial crisis is bigger, structural adjustments to high costs of debt servicing and reduced rates of exchange have caused cuts to the public health budget.10 As a result, many of the countries anxiously look for cost-containment measures and different sources of financing including cost sharing.10 In doing so, no one should be denied access to health care due to financial reasons and Malaysia should not adopt solutions from failed regions that have failed in health care delivery.4 Despite the high-tech medical technology in the health care sector in the United States, 45 million residents are lacking health insurance, including 10 million children who are uninsured.25 One possible suggestion in managing long term health problems is by looking at the Chronic Care Model (CCM) that leads to improved patient care and better health care systems, which is widely practiced for ambulatory care improvement in the United States and internationally.26

Through privatization in Malaysia, the weight of the cost of care was moved to a sizeable proportion of the population that could least afford it. Comparatively, the provision of medical care through the National Health Service in Britain is committed to horizontal equity which describes equal treatment for equal need27 while the Australian experience in health care financing is described as the classical liberal manner in which the government operates.23 Fortunately, countries such as Malaysia and Thailand provided a safety net for primary care and ensured minimal essential care for the high risk groups.28

Champions

Concluding remarks

Multidisciplinary interventions are required to promote health financing, health care and disease prevention.18 In Malaysia, the partnership between the public and private sectors should be encouraged to maximize resources and minimize duplication of health delivery in order to provide equitable health care.19 Subsequently, the community engagement in self care, planning, organizing and management will lead to self sufficiency in health.19 Countries need to get communities involved through social networks to address these problems. One effective way to improve the shortage and distribution imbalance especially in rural areas which is practiced in China is to rely and train the locals as paramedical workers.29

Another option proposed by WHO is providing additional alternatives rather than replacing existing ones.30 Three interrelated strategies to help the poor access health care are to design appropriate training for village health workers (preventive and promotive intervention), design appraisals on programs implemented and introduce community participation.30 The proposed NHFA would be a feasible option as a health care financing mechanism in Malaysia with vested authority in providing equitable and quality services both in the public and private health care services.16 This has also been urged by The Federation of Malaysian Consumers Associations (FOMCA) which has pointed out the benefits that will be gained in implementing the National Health Financing Scheme (NHFS), one of which will be regulating fees charged by the private hospitals and providing the public the freedom of choice to seek treatment either at public or private hospitals in Malaysia.31

Another suggestion of intervention is to establish a National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) to be the main funding source for the public health care sectors which allows compulsory contribution from employers and employees.32 The traditional support systems in some countries were also being commented to have been taken for granted and governments need to mobilize these social networks to take care of these problems.19 In this respect, the development of traditional medicine is encouraged in China where traditional medicine complements western medicine and this practice is allowed in hospitals in order to give the people the choice.19 In Australia, the demand for alternative medicine is increasing steadily33 and findings have shown that the consumer expenditure have doubled from $A1 billion in 1993 to $A2.3 billion in 2000.34 A survey conducted by the Malaysian MOH in 2004 has concluded that 70% of Malaysians have used traditional and complementary based medicine to improve their health or to treat illnesses.35 The fields include Malay traditional medicine, Chinese traditional medicine, Ayurvedic medicine and Natural medicine.35 Utilization of cross-cultural traditional medicine by the various ethnic groups in Malaysia is also gaining popularity.36,37 This has raised significant issues in public health policy.38

Even though the practice of alternative medicine is recognized in statutory form under section 34(1) of Medical Act 1971 (Act 50),37 however the safety and efficacy of these medicine must be ensured through strict regulations37 and public education forums.38 Since the goal of medicine is essentially helping people to improve their health, therefore it is important for medical health professionals to work together with social workers from traditional and complementary medicine by respecting each others' beliefs and training and working as a team.33 Currently guidelines and the passing of the Traditional and Complementary Medicine Bill for the various fields in traditional medicine are being studied carefully by various organizations in Malaysia.32

The Malaysian government has also encouraged private hospitals to take on more social responsibility of the country and the private sectors are responding well to this. Over the last couple of years, there has been an increase in efforts to improve systems and attract foreign workforce. With the Tenth Malaysian Plan in place, it is hoped that the mechanisms set by the government will improve the situation.

References

- 1.Chai PY, Whynes DK, Sach TH. Equity in health care financing: the case of Malaysia. Int J Equity Health. 2008;7:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merican MI, bin Yon R. Health care reform and changes: the Malaysian experience. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2002;14:17–22. doi: 10.1177/101053950201400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juni MH. Public health care provisions: access and equity. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:759–68. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amar Current challenges in health and health care. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2004;16:87–8. doi: 10.1177/101053950401600201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liow TL. Petaling Jaya, Malaysia: Apr 15, 2008. [Accessed April 30, 2008]. Text speech by Minister of Health at: National Conference on Primary Health Care. Available from: http://moh.gov.my/speeches/. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdullah NRW. The private health sector and public policy objectives: the case of Malaysia. [Accessed April 27, 2008];FEA working paper no 2004-3. Published 2004. Available from: http://www.fep.um.edu.my/images/fep/doc/2004%20Pdf/FEA-WP-2004-003.pdf.

- 7.Department of Health Selangor. Annual Report 2006. Department of Health Selangor, Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Health Malaysia. Report of the Director-General of Health Malaysia. Ministry of Health Malaysia; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.bin Yon R, Suleiman AB. Malaysian health care system. In: Wieners WW, editor. Global Health Care Markets: A Comprehensive Guide to Regions, Trends and Opportunities Shaping the International Health Arena (Chapter 22 Malaysia) Jossey-Bass Publ.; San Francisco, CA, USA: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phua KH, Chew AH. Towards a comparative analysis of health systems reforms in the Asia-Pacific Region. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2002;14:9–16. doi: 10.1177/101053950201400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Economic Planning Unit (EPU) [Accessed April 28, 2008];Eighth Malaysia Plan 2001–2005. Available from: http://www.epu.gov.my/web/guest/eightmalaysiaplan.

- 12.Ministry of Health Malaysia. Health Facts 2008. Planning and Development Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health Malaysia. Health Facts 2009. Planning and Development Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Twaddle AC. Health system reforms – toward a framework for international comparisons. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:637–54. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binns C, Boldy D. The burden of disease in the Asia-Pacific region – challenges to public health. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2003;15:77–8. doi: 10.1177/101053950301500201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kananatu K. Healthcare financing in Malaysia. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2002;14:23–8. doi: 10.1177/101053950201400106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry of Health. National Health and Morbidity Survey II. Ministry of Health Malaysia; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Low WY. A journal for public health issues in the Asia Pacific: APJPH. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2008;20:181–2. doi: 10.1177/1010539508320225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yadav H. Community-based health practices and their challenges in the future. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2000;12:1–3. doi: 10.1177/101053950001200101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet. 1971;297:405–12. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shigeru O. Keynote address. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2002;14:3–5. doi: 10.1177/101053950201400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patient's right. [Accessed November 30, 2010];Malaysian Medical Association. Available from: http://www.mma.org.my/Resources/Charters/Patientscharger/PatientsRight/tabid/82/Default.aspx.

- 23.Tripp P. A comparative analysis of health care costs in three selected countries: The United States, The United Kingdom and Australia. Soc Sci Med. 1981;15C:19–30. doi: 10.1016/0160-7995(81)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khoo EM, Richard KM. Primary health care and general practice – a comparison between Australia and Malaysia. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2002;14:59–63. doi: 10.1177/101053950201400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan CK. Privatisation, the state and healthcare reforms: global influences & local contingencies in Malaysia. Proceeding 9th Int. Congr. of World Federation of Public Health Association; November 8–10, 2000; Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coleman K, Austin B, Brach C, Wagner E. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millennium. Health Aff. 2009;28:75–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.West PA. Theoretical and practical equity in the national health service in England. Soc Sci Med. 1981;15C:117–22. doi: 10.1016/0160-7995(81)90025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patrick WK, Cadman EC. Changing emphases in public health and medical education in health care reform. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2002;14(1):35–39. doi: 10.1177/101053950201400108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu TW. Issues of health care financing in the People's Republic of China. Soc Sci Med. 1981;15C:233–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McEvers NC. Health and the assault on poverty in low income countries. Soc Sci Med. 1980;14C:41–57. doi: 10.1016/0160-7995(80)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Healthcare financing scheme long overdue. [Accessed November 28, 2010];New Sunday Times. 2010 Nov 28; Available from: http://www.nst.com.my/nst/articles/28credit2/Article/index_html. http://www.nst.com.my/nst/articles/28credit2/Article/index_html.

- 32.Citizens' Health Initiative. Towards a citizens' proposal for healthcare reforms. Proceeding Nat. Conf. on Health & Healthcare in Changing Environments; April 22–23; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu X, Carlton A-L, Bensoussan A. Development in and challenge for Traditional Chinese Medicine in Australia. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:685–8. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myers SP. Complementary therapies in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2002;31:1132–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee YP, Izatun S, Teh EH, Yuen M. 70% of Malaysians have used alternative medicine. [Accessed November 23, 2010];The Star, November 23, 2010. Available from: http://thestar.com.my/ news/story.asp?file=/2010/11/23/parliament/7482825&sec=parliament.

- 36.Kamil MA, Khoo SB. Cultural health beliefs in a rural family practice: a Malaysian perspective. Aust J Rural Health. 2006;14:2–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2006.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Talib N. Alternative, complementary and traditional medicine in Malaysia. Med Law. 2006;445:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siti ZM, Tahir A, Ida Farah A, et al. Use of traditional and complementary medicine in Malaysia: a baseline study. Complement Ther Med. 2009;17:292–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]