Abstract

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a lethal urological cancer, with incidence and mortality rates increasing by 2-3% per decade. The lack of standard screening tests contributes to the fact that one-third of patients are diagnosed with locally invasive or metastatic disease. Moreover, 20-40% of RCC patients submitted to surgical nephrectomy will develop metastasis. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs responsible for gene regulation at a post-transcriptional level. It is accepted that they are deregulated in cancer and can influence tumor development. Thus, miRNAs are promising RCC biomarkers, since they can be detected using non-invasive methods. They are highly stable and easier to quantify in circulating biofluids. The elevated miRNA stability in circulating samples may be the consequence of their capacity to circulate inside of extracellular microvesicles (EMVs), for example, the exosomes. The EMVs are bilayered membrane vesicles secreted by all cell types. They can be released in the interstitial space or into circulating biofluids, which allows the travelling, binding and entrance of these vesicles in receptor cells. This type of cell communication can shuttle bioactive molecules between cells, allowing the horizontal transference of genetic material. In this review, we focus on circulating miRNAs (miR-210, miR-1233, miR-221, miR-15a, miR-451, miR-508, miR-378) in the biofluids of RCC patients and attempt to establish the diagnostic and prognostic accuracy, their synergic effects, and the pathways involved in RCC biology.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is thought to arise from the renal parenchyma and it is the most common solid tumor in the adult kidney, accounting for 2-3% of all cancers (1). Worldwide mortality from RCC exceeds 100,000 patients each year with the incidence and mortality rate increasing by 2–3% per decade (1–3). RCC is the most lethal common urological cancer, with a cancer-specific mortality of 30–40%, compared to 20% mortality rates for bladder and prostate cancers (1). The high RCC incidence rate could be partially explained by the improvement of the diagnostic tests (computed tomography, MRI and so on) which allows the detection of a significant number of incidental and asymptomatic cases (2). However, there is no standard screening tests for RCC, and one third of patients present with metastatic RCC (mRCC) at the time of diagnosis. Moreover, over the course of the disease, 20-30% of patients treated with surgery will relapse (4).

The RCC frequency in men is 1.5-2.0 times greater than in woman, with an age peak around 60-70 years (5). The exact RCC etiology remains unclear, although lifestyle risk factors such as cigarette smoking and obesity, and iatrogenic factors like hypertension, use of antihypertensive medications and acquired renal cystic disease have been identified as potential risk factors (6, 7).

According to the World Health Organization there are three major RCC histological subtypes in adults: the clear cell RCC (ccRCC) that occurs in 75-80% of cases, the papillary RCC (10-15%) and the chromophobe RCC (4-5%) (1). These histologic subtypes reflect the tumor heterogeneity and the occurrence of distinct molecular alterations during the course of the disease.

Surgical intervention is the primary approach for the treatment of RCC detected at early stage. However, surgery alone has a limited benefit in patients with metastatic disease, except for palliative reasons (3, 8). Until the past decade, the treatment options for patients with mRCC have been extremely limited, as RCC is notoriously resistant to cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiotherapy (9, 10). Prior to the use of antiangiogenic agents, systemic treatment options for mRCC were limited to cytokine therapies interleukin-2 (IL-2) and interferon-alpha (IFN-α), but they were proved to be ineffective since only a small percentage of the patients showed benefit in terms of long term disease-free survival (11, 12). Currently, targeted therapies have become the standard of care for patients with mRCC with significant impact in patient outcome, replacing the cytokine therapy (13).

The targeted therapies include receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antibodies, and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors (mTORs) (3, 14, 15). Although the outcome of patients has improved, many tumors develop resistance to targeted therapies due to compensatory changes within the target pathway that bypass the site of inhibition (13, 16). Usually, resistance to the targeted agents has been shown to develop after a median of 5–11 months of treatment and a small subset of patients do not experience any clinical benefit from the targeted therapy (13).

No standard approaches to biomarker sampling or analysis have been adopted for RCC since many of the putative tumor markers themselves are still under active investigation for further validation (17). The ideal biomarker must be accessible using non-invasive protocols, inexpensive to quantity, specific to the disease of interest, a reliable early indicator of disease before clinical symptoms appear and a way to stratify the disease and assess response to therapy (18). Despite being one of the most rapidly growing areas in cancer research, the establishment of biomarkers in body fluids has not been an easy task (19). One of the major challenges that need to be overcome is the susceptibility to degradation of the circulating biomarkers by proteases and nucleases. On the other hand, there is also the problem of the endogenous production of biomarker molecules by normal cells that may artificially augment the biomarker signals (20, 21).

Plasma and serum have been the focus of extensive research for the past years (22). However, serum and plasma-based tests suitable for clinical use in early tumor detection are currently limited (23, 24). Nowadays, the majority of the routinely used serum markers are proteins and the standard methodologies used to measure them remain labor-intensive (23). The same is true for urine samples. Urine metabolomics analysis is theoretically promising but difficulties with the heterogeneous nature of urine metabolomics, potential contamination of non-human metabolites from genitourinary flora, and special handling requirements have limited the progress of its use as a source of biomarkers for RCC (25).

Of the possible non-invasive biomarkers that have been studied in RCC, the ones that seem more promising are the miRNAs, since they can be detected using non-invasive methods and are easier to quantify when compared to proteins. However, further research is needed in order to validate them (26–28).

MicroRNAs

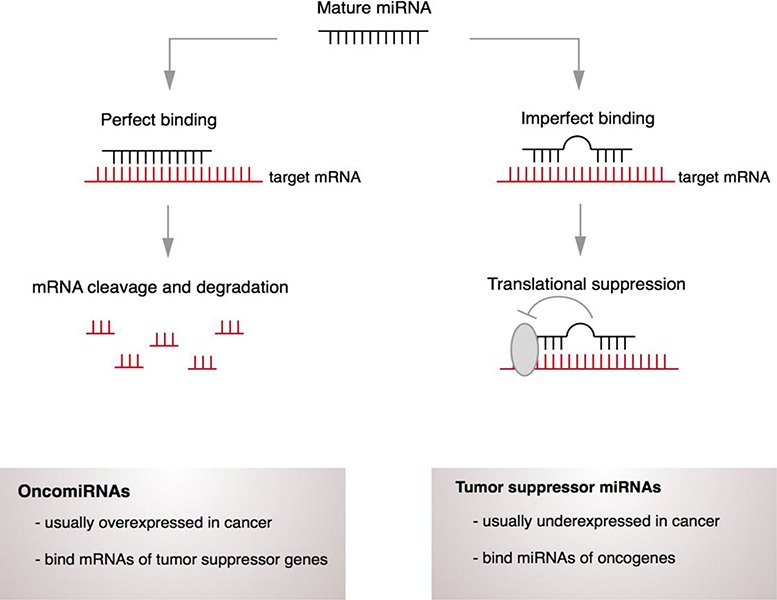

MiRNAs are a class of small non-coding RNAs (19-25 nucleotides in length), that are involved in the regulation of biological processes, including cell proliferation and differentiation. miRNAs regulate gene expression by sequence-selective targeting of mRNAs, leading to their degradation or blockade at the post-transcriptional level, depending on the degree of complementarity between miRNAs and the target mRNA sequence (Figure 1) (29–32). They arise from intergenic or intragenic genomic regions that are transcribed as long primary transcripts. Then, the primary transcripts undergo processing steps that involve Drosha and Dicer enzymes, to form a mature miRNA. The mature miRNA binds to specific regions of target mRNA transcripts and destabilizes the target transcript or blocks its translation (33, 34). MiRNA expression is dynamic, since it is postulated that each miRNA regulates up to 100 different mRNAs and that more than 10000 mRNAs appear to be directly regulated by miRNAs (35). Many miRNAs have been identified to act as oncogenes, tumor suppressors or even modulators of cancer stem cells and metastasis formation (36). OncomiRs are known to down-regulate tumor suppressor genes, and have been reported to be overexpressed in multiple miRNA-profiling studies. On the other hand, tumor suppressor miRNAs are responsible for down-regulating oncogenes, and are mostly under-expressed in cancer (33).

Figure 1.

Mechanism of miRNA action. MiRNA can bind to specific regions of target mRNA transcripts and destabilizes the target transcript and/or blocks its translation.

One of the most important features of miRNAs is that they have different expression patterns in normal cells when compared with cancer cells, which makes them excellent candidates for biomarkers (37, 38). In addition, miRNA expression signatures in blood, serum and plasma are similar between species, as well in individuals of different ages from the same species (38). Specific expression patterns of serum miRNAs have already been identified for pregnancy, diabetes, and different cancers, thus providing evidence that plasma miRNAs contain fingerprints distinctive of certain human conditions (19). Circulating miRNAs are also stable after being submitted to severe conditions such as boiling, very low or high pH, extended storage, and several freeze-thaw cycles, that would normally degrade most RNAs (19). They also seem to be protected from RNase activity, which solves the problem of possible degradation and launches them as one of the top candidates for circulating biomarkers.

Circulating tumor-microvesicles as potential microRNA carriers

Over the past decade, tumors have increasingly been recognized as organs whose complexity approaches and may even exceed that of normal healthy tissues. When analyzed from this point of view, the biology of a tumor can only be understood by studying the individual specialized cell types within it as well as the “tumor microenvironment” that it is assembled during the course of tumorigenesis. This approach contrasts with the earlier view of a tumor as nothing more than a cluster of transformed cells standing alone, whose entire biology could be understood by elucidating their cell-autonomous properties (39).

Cancer cells in primary tumors are surrounded by a complex microenvironment. This microenvironment is composed by numerous types of cells including endothelial cells of the blood and lymphatic circulation, stromal fibroblasts and a variety of bone-marrow-derived cells including macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, TIE-2 expressing monocytes and mesenchymal stem cells (40).

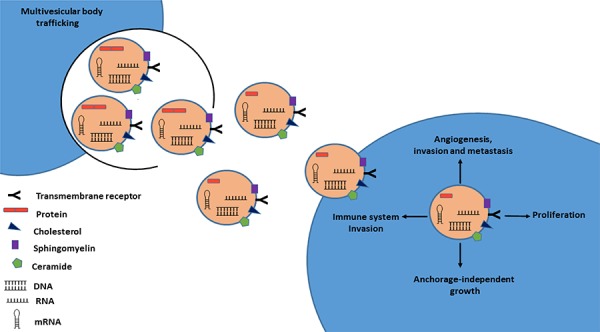

One way of microenvironment modulation is through paracrine and/or systemic signaling between cells. This type of intercellular communication can occur by a direct cell-to-cell contact through adhesion junctions or by releasing of soluble signaling molecules (growth factor, cytokines) by the exchange of cellular fragments such as extracellular membrane microvesicles (EMV) (41). Shed EMVs serve to shuttle bioactive molecules between cells and their cargo can modulate the extracellular microenvironment (42). The EMVs are small circulating fragments (40-5000 nm diameter) with characteristics of the cell origin, that can be categorized into exosomes, microvesicles or ectosomes, apoptotic bodies or Golgi vesicles based on their size, origin, morphology and mode of release (38, 43). The best characterized EMVs are the exosomes, 50- to 100-nm vesicles generated intracellular in multi-vesicular bodies (MVBs) and released directly or upon fusion with the plasma membrane (Figure 2) (42, 44). The EMVs are bilayered membrane vesicles secreted by all cell types that can be released in the interstitial space or into circulating body fluids, which allows the travelling of these vesicles and the posterior binding and entrance in receptors cells (41).

Figure 2.

Schematic model of exosome secretion in cancer cells. Exosome membranes are enriched in cholesterol, sphingomyelin, and ceramide, as well as lipid raft associated proteins. These components allow exosomes to be highly stable in numerous body fluids. Exosomes released from cancer cells transport a variety of molecules (miRNAs, RNAs, DNA, proteins) and can be taken up by neighboring cells and are capable of inducing pathways involved in cancer initiation and progression.

Exosome-mediated cell communication includes, but is not restricted to, direct activation of cell-surface receptors on recipient cells, transfer and translation of mRNAs, transfer of miRNAs and silencing of mRNA targets, transfer of functional proteins and the induction of cell signaling pathways upon their internalization (42, 45). Valadi and co-workers were the first group to observe the existence of miRNAs in exosomes, which can be delivered to another cell, and remain functional in the receptor cells (46).

A recent study performed by King and co-workers provides evidence that microenvironment modulation (oxygen oscillations) promotes exosome release from breast cancer cells, which could be mediated by HIF-1α signaling pathway (47). This scenario is particularly important in RCC where VHL inactivation leads to the accumulation of HIF-1α and the activation of HIF-regulated molecules (2). Moreover, Kahlert and co-workers found that exosomes from serum of pancreatic cancer patients can be used for genomic DNA mutations detection, with impact on cancer prediction and treatment (48). Thus, exosomes can select bioactive molecules and propagate the horizontal transfer of their cargo and, consequently, have an enormous impact on tumor growth, angiogenesis, escape from immune surveillance, extracellular matrix degradation and metastasis (44, 49, 50). Since they are released into the circulation, exosome-dependent signaling may occur not only locally, but also in a paracrine and systemic manner, which can have a direct impact in tumor progression and metastasis (45).

The elevated stability of miRNA in circulating samples is thought to be the result of their capacity to circulate inside of exosomes (42). Exosome membranes are enriched in cholesterol, sphingomyelin, and ceramide as well as lipid raft associated proteins (51, 52). These components allow exosomes to be highly stable and thus be collected from numerous body fluids including blood, urine, breast milk, ascites and saliva (53-58). The lipid content of membranes is important because cholesterol depletion results in the inhibition of EMV release (42, 59). Thus, we hypothesize that higher levels of cholesterol observed in obese individuals can lead to an increase of EMV formation and release which in turn could promote miRNAs networks disruption leading to cardiovascular diseases and cancer development.

Differential expression of miRNA between normal and cancer patients has been reported (60–62). Although normal cells within the peripheral circulation can contribute to exosome population, the primary source of circulating exosomes in cancer patients is the tumor (63). Several reports indicate that cancer cells release more extracellular vesicle than normal cells and that the biomolecular cargo (nucleic acids, proteins and lipids) is reflective of the cell of origin (43). Moreover, miRNA containing tumor-derived exosomes can affect biological processes inside of recipient cells and, consequently, affect the tumor microenvironment (42). MiRNA molecules have also been described in exosomes shed from several tumor cell lines, including lung, glioblastoma and gastric cancers (60, 61, 64). It has also been suggested that tumor derived exosomes could be vehicles involved in the metastization process. Grange and co-workers found that CD105-positive exosomes (containing miRNAs) that were released by renal cell carcinoma stem cells triggered angiogenesis and the formation of a pre-metastatic niche in the lungs, when injected in mice (65). Circulating extracellular vesicles derived from RCC contain miRNAs, such as miR-200c, miR-92, miR-141, miR-19b, miR-29a, miR29c, miR-650, and miR-151. These miRNAs have been associated with tumor invasion and metastasis (37, 65).

Circulating microRNAs in Renal Cell Carcinoma

The majority of the efforts made with the purpose of finding a signature of deregulated miRNAs in RCC have used genome-wide microarray profiling on tissue samples (66, 67). Since microarray allows the analysis of hundreds of miRNAs at the same time, it is an easy way to get an overall view of differentially expressed miRNAs in RCC.

Several up-regulated miRNAs have been described in RCC tissue samples, such as the miR-210 and miR-155, whose expressions can be induced by the hypoxic tumor microenvironment of RCC (68, 69). Furthermore, the down-regulation of miR-141, miR-149 and miR-200c are also described in these tumors. The down-regulation or loss of these miRNAs is associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) (38). MiR-200c can target the ZEB1, a transcription factor that drives the EMT process (70). Youssef and coworkers developed a ‘decision tree’ based on miRNA expression signature of RCC samples (71). The ‘decision tree’ can enable researchers to distinguish different subtypes of RCC. The system has a sensitivity of 97% in distinguishing normal from RCC, 100% for clear cell RCC subtype, 97% for papillary RCC subtype and 100% accuracy in distinguishing oncocytoma from chromophobe RCC subtype (71). While these results are promising, they were generated using a limited number of samples. Furthermore, obtaining tissue samples require the use of invasive biopsy (66).

Hence, profiling miRNA signature in biofluids is attractive strategy. In this regard, only a few studies have assessed circulating miRNA in RCC as potential biomarkers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of circulating miRNAs detected in RCC patients

| MIRNA | POPULATION (SIZE) | TYPE OF SAMPLE | MIRNA REGULATION | CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS | REF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIR-15A | 7 RCC/ 5 chRCC*/6 pRCC/ 5 Onco/ 5 HC | urine | Up | diagnosis of ccRCC | (81) |

| MIR-210 | 34 RCC/ 23 HC | serum | Up | diagnosis of RCC | (77) |

| 68 RCC/ 42 HC | serum | Up | diagnosis of RCC | (76) | |

| MIR-221 | 43 RCC / 34 HC | plasma | Up | diagnosis and prognosis of RCC | (72) |

| MIR-378 | 90 RCC/ 35 HC | serum | Up | diagnosis of RCC | (27) |

| MIR-451 | 90 RCC/ 35 HC | serum | Down | diagnosis of RCC | (27) |

| MIR-508-3P | 10 RCC/ 10 HC | serum | Down | diagnosis of RCC | (80) |

| MIR-1233 | 84 RCC/ 93 HC | serum | Up | diagnosis of RCC | (26) |

RCC, renal cell carcinoma; chRCC, chromophobe RCC; pRCC, papillary RCC; Onco, oncocytoma; HC, healthy controls.

Teixeira and co-workers suggested that plasma level of miR-221 plasma is a potential biomarker of RCC progression. By integrating histopathological characteristics, patients’ age and miR-221 plasma expression levels, the authors proposed that higher circulating expression levels of miR-221 associated with poor overall survival (72). Furthermore, patients with metastatic RCC on diagnosis presented 10.9-fold increase of miR-221 expression when compared to patients with localized disease (72). The miR-221 was identified as a downstream target of EGFR-RAS-RAF-MEK pathway, and the down-regulation of this miRNA is associated with the inhibition of the invasion potential and the secretion of matrix metalloproteinase 2 and 9 (73-75).

The serum levels of miR-210 were proposed as biomarkers for molecular diagnosis of ccRCC by Zhao and coworkers (76). A decrease in serum miR-210 levels was observed after nephrectomy, emphasizing the hypothesis of miRNA release from tumor into circulation (76). Iwamoto and co-workers also observed a higher expression of miR-210 in tumor versus normal tissue samples from 34 RCC patients. However, no statistically significant association was found when matched for age, gender, tumor size or metastases (77). The expression of miR-210 is directly regulated by hypoxia and has the potential to be a biomarker of HIF-α pathway activation. Furthermore, miR-210 has multiple direct targets and exerts its influence on a wide range of cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, mitochondrial metabolism, protein modification, nucleic acid binding, migration and angiogenesis (78).

Redova and coworkers showed that miR-451 is down-regulated in serum samples of RCC patients when compared to healthy individuals. They also demonstrated that miR-378, which is known to promote cell survival and angiogenesis, is up-regulated in serum samples of RCC patients (n=90) (27). However, in the same year Hauser and co-workers, using serum samples of 117 RCC patients, did not observe this up- regulation compared with the levels observed in healthy individuals. Moreover, these authors did not find any statistically significant association between the expression of miR-378 and pT-stage, lymph node/distant metastasis, vascular invasion and Fuhrman grade (79). The contradictions observed between the two studies could be the consequence of differences in the biologic populations (patients and control group) and also the influence of the methodology used for miRNA extraction/purification.

Zhai and co-workers observed a down-regulation of miR-508-3p in biopsy samples of RCC patients and validated the results in 10 plasma samples of the same RCC patients (80). They also proposed that miR-508-3p would play an important role as tumor suppressor gene during tumor formation and that it may serve as novel diagnostic marker for RCC (80).

The high serum levels of miR-1233 were described by Wulfken and co-workers in RCC patients (n=84 patients) compared with healthy controls, with a sensitivity of 77.4% and a specificity of 37.6% (26). Using a bioinformatics approach (miRWalk) the authors suggested that this miRNA can target p53 and BLCAP, well-known tumor suppressor genes (26).

Another biological sample with a potential to be used for molecular biomarkers detection is the urine. Von Brandenstein and co-workers proposed that miR-15a may be an important biomarker aiding in ccRCC detection since it is detectable in the urine of ccRCC patients but is nearly undetectable in the urine of patients with other urinary tumors, and urinary tract inflammation (81). Recently, Komabavashi and co-workers proposed that the down regulation of miR-15a is implicated in the pathogenesis of nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma, where it induces cell proliferation via MYB and cyclin D1 (82).

Correlation between circulating microRNAs, VHL deregulation and renal cell carcinoma

The different RCC histological subtypes reflect differences in the molecular mechanisms involved in tumorigenesis as well as different prognosis. The papillary RCC is characterized by the gain of chromosome material (Trisomy 7, 17), chromophobe RCC is characterized by the loss of genetic material that included monosomy of chromosomes 1, 2, 6, 13, 17 or 21 (83), and the majority of cell RCC is characterized by loss of function of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene (84–87).

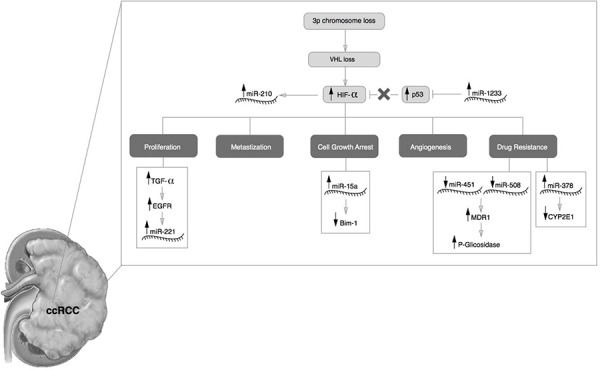

In normoxic conditions, the protein encoded by the VHL gene (pVHL) serves as a recognition site for the regulatory subunits of HIF, targeting them for proteasomal degradation. One of the early molecular events of ccRCC is the loss of pVHL function (a consequence of the loss of the short arm of chromosome 3), which stops the degradation of HIF and leads to its accumulation in the cytoplasm and further migration to the nucleus where it binds to hypoxia-regulated genes. Once activated, these genes are involved in pathways responsible for angiogenesis, proliferation, glucose metabolism, pH regulation and metastatic disease (2, 87–89). Based on the previous section on circulating microRNAs in renal cell carcinoma (see above) we propose a possible mechanistic association between miRNAs and the VHL signaling pathway (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

VHL and miRNA. Proposed mechanistic model for the role of miR-210, miR-1233, miR-221, miR-15a, miR-451, miR-508-3p, miR-378 during the ccRCC development.

VHL deregulation induces the expression of miR-210 (90). MiR-1233, which is rapidly induced by hypoxia, in turn work together with HIF-α to regulate the hypoxic response from the cell (91, 92). Thus, we hypothesize that miR-210 is induced by hypoxia and miR-1233 helps to maintain the hypoxic status.

The VHL is also responsible for EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) turnover. Studies performed by Zhou and co-workers showed that the half-life of EGFR is longer in cells lacking the VHL gene compared to normal cells (90). The EGFR stabilization in membrane and the TGFα biodisponibility (as a consequence of VHL deregulation) can promote the constant activation of EGFR-RAS-RAF-MEK leading to a higher cellular proliferation. Since the miR-221 is induced by EGFR-RAS-RAF-MEK pathway, it is fitting that higher levels of this miRNA is found in patients with ccRCC (72). MiR-221 can actively repress TIMP-3 and cell cycle inhibitor proteins p27/Kip1 and p57, facilitating cell proliferation, self-renewal and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of RCC (93, 94).

Recently, Camps and co-workers observed an increase of miR-378 at lower concentrations of oxygen, suggesting that this miRNA could be a potential biomarker for hypoxia (95). It is known that miR-378 inhibits the expression of CYP2E1, which could be implicated in chemotherapy responses (96).

Kozakowski and co-workers found a higher expression of Bmi-1 (B lymphoma mouse Moloney leukemia virus insertion region) during RCC development. Bmi-1 is indispensable for the self-renewal of neural and hematopoietic stem cells, and a high expression is observed in papillary RCC and oncocytomas. However, in ccRCC, Bmi-1 expression was inversely correlated (97). Bim-1 down-regulation in ccRCC could be explained by the capacity of miR-15a to target the Bmi-1 3’ UTR mRNA leading to it degradation or translational repression (98).

Other circulating miRNAs deregulated in RCC were the miR-451 and miR-508-3p (80, 99). MiRNA-451 and miR-508-3p are involved in the regulation of MDR1 gene (multidrug resistance 1 gene) that encode the human P-glycoprotein (100, 101). The elevated levels of P-glycoprotein in cytoplasm and membranes are associated with drug-resistance of tumors (100). The significant role of P-glycoprotein in drug pharmacokinetics is suggested by its location in the adrenal gland and in proximal tubules of the kidney (102). MiR-451 reduces the expression of MDR1 mRNA and P-glycoprotein. A reduction of miR-451 and miR-508-3p could be reason why RCC is notoriously resistant to conventional therapeutics.

Conclusion

The stability and “anti-degradation” nature of exosomes in body fluids and the variety of molecules that they carry, such as miRNAs, makes them an ideal target for biomarkers discovery since their cargo reflects the characteristics of the cell of origin. Nevertheless, the knowledge regarding the mechanisms in which miRNAs are selected and incorporated in exosomes is limited and further investigations is needed to clarify the biological impact of these molecules in distant sites of the body. In the future, clarification of these mechanisms will enable the elucidation of the metastatic process and the discovery of new cancer therapies. Several studies were able to detect circulating miRNAs in body fluids of RCC patients, supporting their suitability as biomarkers. The use of biological fluids such as plasma, serum and urine may open the door to the so called “liquid biopsies”, a less invasive method that could effectively overcome the challenges associated to conventional tissue sampling and provide more sensitive biomarkers. However, the establishment of standard protocols for isolation and quantification of miRNAs are needed in order to implement their use as biomarkers in the clinical practice.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the Liga Portuguesa Contra o Cancro—Centro Regional do Norte (Portuguese League Against Cancer).

References

- 1.Bhatt JR, Finelli A. Landmarks in the diagnosis and treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11(9):517–25. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2014.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dias F, Teixeira AL, Santos JI, et al. Renal cell carcinoma development and miRNAs: a possible link to the EGFR pathway. Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14(14):1793–803. doi: 10.2217/pgs.13.184. http://dx.doi.org/10.2217/pgs.13.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bex A, Jonasch E, Kirkali Z, et al. Integrating surgery with targeted therapies for renal cell carcinoma: current evidence and ongoing trials. Eur Urol. 2010;58(6):819–28. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.08.029. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inman BA, Harrison MR, George DJ. Novel immunotherapeutic strategies in development for renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2013;63(5):881–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.10.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majid N, Ismaili N, Amzerin M, et al. Targeted therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Current treatment and future directions. Clinical Cancer Investigation Journal. 2013;2(3):195–201. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/2278-0513.119257. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ljungberg B, Campbell SC, Choi HY, et al. The epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2011;60(4):615–21. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.049. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decastro GJ, McKiernan JM. Epidemiology, clinical staging, and presentation of renal cell carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35(4):581–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2008.07.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta K, Miller JD, Li JZ, et al. Epidemiologic and socioeconomic burden of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): a literature review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34(3):193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.12.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motzer RJ, Russo P, Nanus DM, et al. Renal cell carcinoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 1997;21(4):185–232. doi: 10.1016/s0147-0272(97)80007-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0147-0272(97)80007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen HT, McGovern FJ. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2477–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra043172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang JC, Sherry RM, Steinberg SM, et al. Randomized study of high-dose and low-dose interleukin-2 in patients with metastatic renal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(16):3127–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.02.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coppin C, Porzsolt F, Awa A, et al. Immunotherapy for advanced renal cell cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005(1):Cd001425. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001425.pub2. Pubmed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravaud A, Gross-Goupil M. Overcoming resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(8):996–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.01.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abe H, Kamai T. Recent advances in the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Int J Urol. 2013;20(10):944–55. doi: 10.1111/iju.12187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/iju.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patard JJ, Pignot G, Escudier B, et al. ICUD-EAU International Consultation on Kidney Cancer 2010: treatment of metastatic disease. Eur Urol. 2011;60(4):684–90. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rini BI, Flaherty K. Clinical effect and future considerations for molecularly-targeted therapy in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2008;26(5):543–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.03.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ngo TC, Wood CG, Karam JA. Biomarkers of renal cell carcinoma. Urologic oncology. 2014;32(3):243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.07.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber JA, Baxter DH, Zhang S, et al. The microRNA spectrum in 12 body fluids. Clin Chem. 2010;56(11):1733–41. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.147405. http://dx.doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2010.147405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X, Ba Y, Ma L, et al. Characterization of microRNAs in serum: a novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res. 2008;18(10):997–1006. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.282. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cr.2008.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li L, Choi JY, Lee KM, et al. DNA methylation in peripheral blood: a potential biomarker for cancer molecular epidemiology. J Epidemiol. 2012;22(5):384–94. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20120003. http://dx.doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20120003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niers TMH, Richel DJ, Meijers JCM, et al. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in the Circulation in Cancer Patients May Not Be a Relevant Biomarker. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(5):e19873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019873. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas CM, Sweep CG. Serum tumor markers: past, state of the art, and future. Int J Biol Markers. 2001;16(2):73–86. Pubmed. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duffy MJ. Role of tumor markers in patients with solid cancers: A critical review. Eur J Intern Med. 2007;18(3):175–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2006.12.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duffy MJ. Tumor markers in clinical practice: a review focusing on common solid cancers. Med Princ Pract. 2013;22(1):4–11. doi: 10.1159/000338393. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000338393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ganti S, Weiss RH. Urine metabolomics for kidney cancer detection and biomarker discovery. Urol Oncol. 2011;29(5):551–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.05.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wulfken LM, Moritz R, Ohlmann C, et al. MicroRNAs in renal cell carcinoma: diagnostic implications of serum miR-1233 levels. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025787. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Redova M, Poprach A, Nekvindova J, et al. Circulating miR-378 and miR-451 in serum are potential biomarkers for renal cell carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2012;10 doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-10-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu X, Weng L, Li X, et al. Identification of a 4-microRNA signature for clear cell renal cell carcinoma metastasis and prognosis. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e35661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035661. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gambari R, Fabbri E, Borgatti M, et al. Targeting microRNAs involved in human diseases: a novel approach for modification of gene expression and drug development. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82(10):1416–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.08.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, Zhao H, Gao Y, et al. Secretory miRNAs as novel cancer biomarkers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826(1):32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.03.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melo SA, Esteller M. A precursor microRNA in a cancer cell nucleus: get me out of here! Cell Cycle. 2011;10(6):922–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.6.15119. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/cc.10.6.15119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melo SA, Esteller M. Dysregulation of microRNAs in cancer: playing with fire. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(13):2087–99. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.08.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aslam MI, Taylor K, Pringle JH, et al. MicroRNAs are novel biomarkers of colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96(7):702–10. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6628. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bjs.6628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Negrini M, Nicoloso MS, Calin GA. MicroRNAs and cancer--new paradigms in molecular oncology. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21(3):470–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.03.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hummel R, Hussey DJ, Haier J. MicroRNAs: predictors and modifiers of chemo- and radiotherapy in different tumour types. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(2):298–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.10.027. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cho WC. MicroRNAs: potential biomarkers for cancer diagnosis, prognosis and targets for therapy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42(8):1273–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.12.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chow TF, Youssef YM, Lianidou E, et al. Differential expression profiling of microRNAs and their potential involvement in renal cell carcinoma pathogenesis. Clin Biochem. 2010;43(1-2):150–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.07.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grange C, Collino F, Tapparo M, et al. Oncogenic micro-RNAs and Renal Cell Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2014;4(49) doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00049. Pubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanahan D, Weinberg R. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joyce JA, Pollard JW. Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(4):239–52. doi: 10.1038/nrc2618. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrc2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sato-Kuwabara Y, Melo SA, Soares FA, et al. The fusion of two worlds: Non-coding RNAs and extracellular vesicles - diagnostic and therapeutic implications (Review). Int J Oncol. 2015;46(1):17–27. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2712. http://dx.doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2014.2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.D'Souza-Schorey C, Clancy JW. Tumor-derived microvesicles: shedding light on novel microenvironment modulators and prospective cancer biomarkers. Genes Dev. 2012;26(12):1287–99. doi: 10.1101/gad.192351.112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.192351.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nawaz M, Camussi G, Valadi H, et al. , The emerging role of extracellular vesicles as biomarkers for urogenital cancers: Nat Rev Urol 2014November18http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2014.301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henderson MC, Azorsa DO. The Genomic and Proteomic Content of Cancer Cell-Derived Exosomes. Frontiers in Oncology. 2012;2 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00038. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2012.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Svensson KJ, Belting M. Role of extracellular membrane vesicles in intercellular communication of the tumour microenvironment. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41(1):273–6. doi: 10.1042/BST20120248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1042/BST20120248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(6):654–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.King HW, Michael MZ, Gleadle JM. Hypoxic enhancement of exosome release by breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2012;12(421):1471–2407. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-421. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kahlert C, Melo SA, Protopopov A, et al. Identification of double-stranded genomic DNA spanning all chromosomes with mutated KRAS and p53 DNA in the serum exosomes of patients with pancreatic cancer. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(7):3869–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C113.532267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C113.532267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muralidharan-Chari V, Clancy JW, Sedgwick A, et al. Microvesicles: mediators of extracellular communication during cancer progression. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 10):1603–11. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064386. http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/jcs.064386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Doormaal FF, Kleinjan A, Di Nisio M, et al. Cell-derived microvesicles and cancer. Neth J Med. 2009;67(7):266–73. Pubmed. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simpson RJ, Jensen SS, Lim JW. Proteomic profiling of exosomes: current perspectives. Proteomics. 2008;8(19):4083–99. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800109. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pmic.200800109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Gassart A, Geminard C, Fevrier B, et al. Lipid raft-associated protein sorting in exosomes. Blood. 2003;102(13):4336–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0871. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2003-03-0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keller S, Ridinger J, Rupp AK, et al. Body fluid derived exosomes as a novel template for clinical diagnostics. J Transl Med. 2011;9:86. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-9-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li QL, Bu N, Yu YC, et al. Exvivo experiments of human ovarian cancer ascites-derived exosomes presented by dendritic cells derived from umbilical cord blood for immunotherapy treatment. Clin Med Oncol. 2008;2:461–7. doi: 10.4137/cmo.s776. Pubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonzales PA, Zhou H, Pisitkun T, et al. Isolation and purification of exosomes in urine. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;641:89–99. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-711-2_6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60761-711-2_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou Q, Li M, Wang X, et al. Immune-related microRNAs are abundant in breast milk exosomes. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8(1):118–23. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.8.118. http://dx.doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.8.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Navabi H, Croston D, Hobot J, et al. Preparation of human ovarian cancer ascites-derived exosomes for a clinical trial. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2005;35(2):149–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.06.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ogawa Y, Kanai-Azuma M, Akimoto Y, et al. Exosome-like vesicles with dipeptidyl peptidase IV in human saliva. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31(6):1059–62. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.1059. http://dx.doi.org/10.1248/bpb.31.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Del Conde I, Shrimpton CN, Thiagarajan P, et al. Tissue-factor-bearing microvesicles arise from lipid rafts and fuse with activated platelets to initiate coagulation. Blood. 2005;106(5):1604–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1095. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2004-03-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Skog J, Wurdinger T, van Rijn S, et al. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(12):1470–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1800. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncb1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rabinowits G, Gercel-Taylor C, Day JM, et al. Exosomal microRNA: a diagnostic marker for lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2009;10(1):42–6. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.006. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3816/CLC.2009.n.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chan JA, Krichevsky AM, Kosik KS. MicroRNA-21 is an antiapoptotic factor in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(14):6029–33. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taylor DD, Gercel-Taylor C. MicroRNA signatures of tumor-derived exosomes as diagnostic biomarkers of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.04.033. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ohshima K, Inoue K, Fujiwara A, et al. Let-7 microRNA family is selectively secreted into the extracellular environment via exosomes in a metastatic gastric cancer cell line. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grange C, Tapparo M, Collino F, et al. Microvesicles released from human renal cancer stem cells stimulate angiogenesis and formation of lung premetastatic niche. Cancer Res. 2011;71(15):5346–56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Osanto S, Qin Y, Buermans HP, et al. Genome-wide microRNA expression analysis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma by next generation deep sequencing. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038298. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.White NM, Khella HW, Grigull J, et al. miRNA profiling in metastatic renal cell carcinoma reveals a tumour-suppressor effect for miR-215. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(11):1741–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wan G, Xie W, Liu Z, et al. Hypoxia-induced MIR155 is a potent autophagy inducer by targeting multiple players in the MTOR pathway. Autophagy. 2014;10(1):70–9. doi: 10.4161/auto.26534. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/auto.26534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Camps C, Buffa FM, Colella S, et al. hsa-miR-210 Is induced by hypoxia and is an independent prognostic factor in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(5):1340–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1755. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang Y, Ahn YH, Chen Y, et al. ZEB1 sensitizes lung adenocarcinoma to metastasis suppression by PI3K antagonism. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(6):2696–708. doi: 10.1172/JCI72171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1172/JCI72171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Youssef YM, White NM, Grigull J, et al. Accurate molecular classification of kidney cancer subtypes using microRNA signature. Eur Urol. 2011;59(5):721–30. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.01.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Teixeira AL, Ferreira M, Silva J, et al. Higher circulating expression levels of miR-221 associated with poor overall survival in renal cell carcinoma patients. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(5):4057–66. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1531-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13277-013-1531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shah MY, Calin GA. MicroRNAs miR-221 and miR-222: a new level of regulation in aggressive breast cancer. Genome Med. 2011;3(8):56. doi: 10.1186/gm272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/gm272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang C, Zhang J, Hao J, et al. High level of miR-221/222 confers increased cell invasion and poor prognosis in glioma. J Transl Med. 2012;10:119. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-119. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-10-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Santos JI, Teixeira AL, Dias F, et al. Influence of peripheral whole-blood microRNA-7 and microRNA-221 high expression levels on the acquisition of castration-resistant prostate cancer: evidences from in vitro and in vivo studies. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(7):7105–13. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1918-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13277-014-1918-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhao A, Li G, Peoc'h M, et al. Serum miR-210 as a novel biomarker for molecular diagnosis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Exp Mol Pathol. 2013;94(1):115–20. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.10.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iwamoto H, Kanda Y, Sejima T, et al. Serum miR-210 as a potential biomarker of early clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2014;44(1):53–8. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2169. http://dx.doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2013.2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chan SY, Loscalzo J. MicroRNA-210: a unique and pleiotropic hypoxamir. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(6):1072–83. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.6.11006. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/cc.9.6.11006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hauser S, Wulfken LM, Holdenrieder S, et al. Analysis of serum microRNAs (miR-26a-2*, miR-191, miR-337-3p and miR-378) as potential biomarkers in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36(4):391–4. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.04.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhai Q, Zhou L, Zhao C, et al. Identification of miR-508-3p and miR-509-3p that are associated with cell invasion and migration and involved in the apoptosis of renal cell carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;419(4):621–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.02.060. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.von Brandenstein M, Pandarakalam JJ, Kroon L, et al. MicroRNA 15a, inversely correlated to PKCalpha, is a potential marker to differentiate between benign and malignant renal tumors in biopsy and urine samples. Am J Pathol. 2012;180(5):1787–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.01.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Komabayashi Y, Kishibe K, Nagato T, et al. Downregulation of miR-15a due to LMP1 promotes cell proliferation and predicts poor prognosis in nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(1):25–33. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23570. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajh.23570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.An J, Choi J, Shin BK, et al. Chromogenic in situ hybridization detection of chromosome 7 and 17 abnormalities in renal cell carcinomas and comparison to flow cytometric DNA ploidy patterns. Basic and Applied Pathology. 2008;1(2):66–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-9294.2008.00015.x. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chou A, Toon C, Pickett J, et al. von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Front Horm Res. 2013;41:30–49. doi: 10.1159/000345668. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000345668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kaelin WG., Jr. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene and kidney cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(18 Pt 2):6290S–5S. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-sup-040025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-sup-040025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor, hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) degradation, and cancer pathogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2003;13(1):83–9. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00103-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1044-579X(02)00103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Smaldone MC, Maranchie JK. Clinical implications of hypoxia inducible factor in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2009;27(3):238–45. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.12.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Loughlin KR. Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF): its central role in renal cell cancer targeted therapy. Urol Oncol. 2009;27(3):236–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.08.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Furniss D, Harnden P, Ali N, et al. Prognostic factors for renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34(5):407–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.12.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhou L, Yang H. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein promotes c-Cbl-independent poly-ubiquitylation and degradation of the activated EGFR. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023936. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0023936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sermeus A, Michiels C. Reciprocal influence of the p53 and the hypoxic pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2011;26(2):e164. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2011.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.An WG, Kanekal M, Simon MC, et al. Stabilization of wild-type p53 by hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Nature. 1998;392(6674):405–8. doi: 10.1038/32925. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/32925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Miller TE, Ghoshal K, Ramaswamy B, et al. MicroRNA-221/222 confers tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer by targeting p27Kip1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(44):29897–903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804612200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M804612200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Teixeira AL, Gomes M, Medeiros R. EGFR signaling pathway and related-miRNAs in age-related diseases: the example of miR-221 and miR-222. Front Genet. 2012;3:286. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00286. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2012.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Camps C, Saini HK, Mole DR, et al. Integrated analysis of microRNA and mRNA expression and association with HIF binding reveals the complexity of microRNA expression regulation under hypoxia. Mol Cancer. 2014;13(28):1476–4598. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1476-4598-13-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mohri T, Nakajima M, Fukami T, et al. Human CYP2E1 is regulated by miR-378. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79(7):1045–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.11.015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kozakowski N, Soleiman A, Pammer J. BMI-1 expression is inversely correlated with the grading of renal clear cell carcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2008;14(1):9–13. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9006-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12253-008-9006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bhattacharya R, Nicoloso M, Arvizo R, et al. MiR-15a and MiR-16 control Bmi-1 expression in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(23):9090–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2552. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Redova M, Poprach A, Nekvindova J, et al. Circulating miR-378 and miR-451 in serum are potential biomarkers for renal cell carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2012;10(55):1479–5876. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-10-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Katayama K, Noguchi K, Sugimoto Y. Regulations of P-Glycoprotein/ABCB1/MDR1 in Human Cancer Cells. New Journal of Science 2014. 2014:10. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shang Y, Zhang Z, Liu Z, et al. miR-508-5p regulates multidrug resistance of gastric cancer by targeting ABCB1 and ZNRD1. Oncogene. 2014;33(25):3267–76. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.297. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/onc.2013.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ambudkar SV, Kimchi-Sarfaty C, Sauna ZE, et al. P-glycoprotein: from genomics to mechanism. Oncogene. 2003;22(47):7468–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206948. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1206948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]