Abstract

SIRT2 is a protein deacetylase with tumor suppressor activity in breast and liver tumors where it is mutated, however, the critical substrates mediating its antitumor activity are not fully defined. Here we demonstrate that SIRT2 binds, deacetylates and inhibits the peroxidase activity of the anti-oxidant protein peroxiredoxin (Prdx-1) in breast cancer cells. Ectopic overexpression of SIRT2, but not its catalytically dead mutant, increased intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which led to increased levels of an over-oxidized and multimeric form of Prdx-1 with activity as a molecular chaperone. Elevated levels of SIRT2 sensitized breast cancer cells to intracellular DNA damage and cell death induced by oxidative stress, as associated with increased levels of nuclear FOXO3A and the pro-apoptotic BIM protein. Additionally, elevated levels of SIRT2 sensitized breast cancer cells to arsenic trioxide, an approved therapeutic agent, along with other intracellular ROS-inducing agents. Conversely, antisense RNA-mediated attenuation of SIRT2 reversed ROS-induced toxicity as demonstrated in a zebrafish embryo model system. Collectively, our findings suggest that the tumor suppressor activity of SIRT2 requires its ability to restrict the anti-oxidant activity of Prdx-1, thereby sensitizing breast cancer cells to ROS-induced DNA damage and cell cytotoxicity.

INTRODUCTION

SIRT2 is a predominantly cytoplasmic member of the class III histone deacetylases (HDACs), or sirtuins, which function as NAD+-dependent lysine deacetylases (1–3). Similar to HDAC6, SIRT2 co-localizes with microtubules in the cytosol and de-acetylates lysine 40 on α-tubulin (2). During G2/M phase of the cell cycle, SIRT2 is nuclear, where it de-acetylates histone protein residues H4K16, H3K56 and H3K18 as well as the BUB1 related kinase (BUBR1), thereby controlling the activity of the APC/C (anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome) and normal mitotic progression (4–6). Because of this activity, SIRT2 prevents chromosomal instability during mitosis (4,5). SIRT2 has also been recognized as a tumor suppressor, since its loss in mice is associated with mammary tumors and hepatocellular carcinomas (5). Among other notable substrates de-acetylated by SIRT2 are metabolic enzymes, including G6PD (glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase), ACLY (ATP citrate lyase) and PGAM (phosphoglycerate mutase) (7–9). Oxidative stress has been shown to induce SIRT2-mediated deacetylation of the transcription factor FOXO3a (10). This induces the transcriptional activity of FOXO3a, causing increased expression of its target genes, including BIM (11). In NIH3T3 cells, ectopic over expression of SIRT2 was also shown to induce BIM and promote cell death following exposure to hydrogen peroxide (10). Recently, SIRT2 was shown to interact with RIP3 (receptor interacting protein 3) and deacetylate RIP1 leading to the formation of a stable RIP1/RIP3 complex and promotion of TNFα-induced necroptosis (12).

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a toxic byproduct of normal cellular processes in aeorobic organisms and is detoxified by antioxidant enzymes including catalase, glutathione peroxidases and peroxiredoxins (Prdxs) (13,14). Prdxs are a family of ubiquitously expressed, 22–27 kDa, thiol-dependent peroxidases, with a conserved cysteine residue (15,16). Prdx-1 is a two-cysteine residue member of the PRDX family of proteins (15,16). Prdx-1 exists as a homodimer and reduces H2O2, utilizing thioredoxin (TRX) as the electron donor for the anti-oxidation (14,16). Prdx-1 is expressed at high levels in the cytosol of transformed cells and is further induced by oxidative stress, e.g., due to exposure to H2O2, which oxidizes the conserved cysteine of Prdx-1 to sulfenic acid (15,16). Besides its cytoprotective antioxidant function, Prdx-1 plays a role in cellular processes involving redox signaling and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (17,18). In the present studies, we determined that SIRT2 binds and acts as a deacetylase for Prdx-1. Whereas knockdown of SIRT2 induces acetylation, ectopic overexpression of SIRT2 deacetylates and inhibits the ROS-neutralizing, antioxidant activity of Prdx-1. This sensitized breast cancer cells to DNA damage and apoptosis induced by H2O2 through a FOXO3a-BIM mediated cell death mechanism. Consistent with this, SIRT2 overexpression also increased cell death induced by ROS-inducing agents, including arsenic trioxide (AT) and menadione.

Materials and Methods

Reagents, antibodies and plasmids

Arsenic trioxide and menadione were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. All antibodies were obtained from commercial sources. Detailed descriptions of the antibodies are provided in the Supplemental Methods.

Cell culture

The breast cancer MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, as well as HEK293 cells were obtained from ATCC. Cells were thawed, passaged and refrozen in aliquots. Cells were used within 6 months of thawing or obtaining from ATCC. The ATCC utilizes short tandem repeat (STR) profiling for characterization and authentication of cell lines. MCF-7 and HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and passaged 2–3 times per week. MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 media containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and passaged 2–3 times per week (19,20). Logarithmically growing cells were exposed to the designated concentrations and exposure interval of the drugs. Following these treatments, cells were washed free of the drug(s) using 1X PBS, and pelleted prior to performing the studies described below.

Immunoprecipitation of Prdx-1 and SIRT2

Following treatments, cells were washed with 1X PBS, then trypsinized and pelleted. Total cell lysates were combined with class-specific IgG or 2 μg of anti-Prdx-1 or anti-HA (HA-SIRT2) or anti-FLAG M2 antibody and incubated with rotation overnight at 4°C. The following day, protein A beads were added and the lysate bead mixture was rotated for 90 minutes 4°C. The beads were washed with 1X PBS three times and sample buffer was added. The beads were boiled and the samples were loaded for SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses were conducted for Prdx-1, SIRT2 or acetyl lysine, as previously described (19,20).

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses

Seventy five micrograms of total cell lysates were used for SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses, as previously described (21).

Confocal microscopy

MCF-7 or MDA-MB231 cells were labeled with immunofluorescence-tagged antibodies, as previously described (22).

Assessment of PI positive cells

Untreated or drug-treated cells were stained with propidium iodide, and the percentage of PI positive cells was determined by flow cytometry, as previously described (21,22).

Peroxiredoxin activity assay

The peroxiredoxin activity assay was carried out according to manufacturer’s instructions (Redoxica) and as previously described (23). Briefly, cells were collected by trypsinization. The cells were washed with 1X PBS and then sonicated in the activity assay buffer. The total reaction volume of 150 μl contained 50 mM HEPES-NaOH buffer, E.coli thioredoxin, mammalian thioredoxin reductase and NADPH. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 2 μl of 10 mM hydrogen peroxide. NADH oxidation was monitored for 10 minutes at 340 nm.

Gene transfection and interaction studies

MCF-7 and HEK293 cells were transiently transfected according to the instructions of the manufacturer using Fugene 6 with plasmids containing scrambled oligonucleotide (control shRNA) or shRNA to SIRT2 containing a 21-nucleotide sequence, corresponding to SIRT2 mRNA—5′-GAAACATCCGGAACCCTTC-3′, as previously described (24). For interaction studies, HEK293 cells were transfected with pcDNA (control vector) with or plasmids for HA-SIRT2 or FLAG-Prdx-1.

Comet assay

DNA damage and repair at an individual cell level was determined by the comet assay as previously described (19, 20). A detailed method is provided in the Supplemental Methods.

ROS assay

MDA-MB231 cells were grown in black 96-well plates overnight at 37°C. The next day, the cells were treated with hydrogen peroxide for 30 minutes at 37°C. The media was aspirated, and the cells were washed with 1 X PBS and DCF-DA in phenol red free media at a final concentration of 10 μM was added to the cells and incubated for 30 minutes. The dye was washed with 1 X PBS and the fluorescence was read using a BioTek fluorescence plate reader (19).

2-Dimensional Differential In-Gel Electrophoresis (DIGE)

S100 cytosolic extracts were prepared from HEK293 vector and SIRT2 knockdown cell lines. Equal amounts of protein were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-acetyl lysine antibody. The proteins were eluted with glycine buffer (pH 2.7). The proteins were then subjected to in vitro labeling with Cy-3 and Cy-5 N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester. Cy-2 was used as an internal standard. The samples were subjected to isoelectric focusing and then separated in a second dimension by SDS PAGE. The gels were fixed, stained and protein spots were analyzed using GE Healthcare DeCyder software. The protein spots of interest were subjected to automated in-gel tryptic digestion and MALDI/MS/MS spectra were performed with 4800 Proteomics Analyzer MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems) (24,25).

High molecular weight oligomer formation

MDA-MB-231 and HEK293 cells were exposed to the indicated concentration of hydrogen peroxide for different time points and the lysates were resolved in a 8% native PAGE electrophoresis. The formation of high molecular weight oligomers were visualized with anti-oxidized-Prdx-1 antibody, as previously described (18,26). In vivo over-oxidation of Prdx-1 was determined, as previously described (27).

In vitro chaperone activity of Prdx-1

HEK293, MDA-MB-231, and MCF7 cells stably transfected with vector, or SIRT2 cDNA were treated with H2O2 for 30 minutes, respectively, and the cells were harvested and lysed with native lysis buffer. Protein concentrations were measured using a BCA kit. Endogenous oligomers and multimers of Prdx-1 protein were immunoprecipitated using Dynabeads® M-280 sheep anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) and anti-peroxiredoxin-1 (LF-MA0214, AbFrontier) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The immunoprecipitated peroxiredoxin 1 and Dynabeads were used for chaperone activity assay as previously described (18,26). Briefly, each reaction contained 2 μM malate dehydrogenase (MDH) and immunoprecipitated chaperone with Dynabeads in 200 μL of 50 mM HEPES-KOH buffer (pH 7.5). The chaperone activity was monitored by measuring the absorbance (320 nm) in a BioTeck SynergyMx plate reader at 43 °C for 2 hours.

Zebra fish studies

Wild Type (AB) zebrafish were maintained using standard procedures (28). Zebrafish embryos and larvae were obtained by natural mating. Morpholino oligonucleotides were injected into yolk at the one-cell stage using an IM300 microinjector (Narishige) (29). The SIRT2 MO (Genetools LLC, Philomath, OR, USA) were designed against the splice-donor sites of exon 6 of SIRT2: 5′-TATGTAAAGTCAGACCTGTTTGTG-3′. SIRT2 MO was injected (0.5 nL) into the yolk of 1-cell-stage zebrafish embryos at a final quantity of 4 ng. To validate the knockdown, total RNA was extracted from 48 hpf embryos using TRIZOL reagent. Two hundred nanograms of total RNA was reverse transcribed using a high-capacity reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) following manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative RT-PCR was carried out using SYBR green. For evaluation of toxicity, 48 hpf embryos injected with SIRT2 MO or a 5-bp mismatch control were treated with the indicated concentrations of hydrogen peroxide. At the end of 48 hours of treatment no mortality was observed but there were morphological abnormalities, as previously described (29). The embryos were placed in tricaine solution and imaged using an epifluorescence microscope. For estimation of the ROS, 48 hpf embryos injected with the SIRT2 MO or 5-bp mismatch control was treated with hydrogen peroxide for 30 minutes. The embryos were then incubated with 50 μM DCF-DA (Invitrogen). Individual embryos were transferred to each well of a 96 well plate and read using a plate reader. At least six embryos per experimental condition were used.

RESULTS

SIRT2 binds and deacetylates Prdx-1

Among the known cytosolic targets of deacetylation by SIRT2 is α-tubulin (2). As shown in Figure 1A, knockdown of SIRT2 with two separate shRNAs stably transduced into HEK-293 cells induced the acetylation of α-tubulin, without altering the levels of the total α-tubulin. Additionally, lysates from cells transduced with the control shRNA or SIRT2 shRNA were also immunoblotted with anti-acetyl-lysine antibody, again demonstrating increased acetylation of several proteins, including α-tubulin and histone H3 (Figure 1B). We next performed the 2-dimensional DIGE analysis on the S100 cytosolic extracts from HEK293 shRNA control and SIRT2 knockdown cell lines. Figure 1C demonstrates a representative 2-dimensional-gel image showing the protein spots exhibiting more than a two-fold difference in the mobility between the vector control and SIRT2 KD treated samples. One of the spots demonstrating a 2.15-fold change in its mobility was identified by mass spectrometry to be peroxiredoxin-1 (Prdx-1). We also identified phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1) and malate dehydrogenase (MDH) (Figure 1C). To confirm that SIRT2 interacts with Prdx-1, we introduced the FLAG-tagged Prdx-1 and HA-tagged SIRT2 into HEK293 cells. The cells were lysed, and the anti-HA antibody immunoprecipitates were then immunoblotted with the anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies. As shown in Figure 2A, the epitope-tagged Prdx-1 co-immunoprecipitated with the epitope-tagged SIRT2. We further confirmed that the endogenous Prdx-1 also co-immunoprecipitated with the FLAG-tagged SIRT2 introduced into MDA-MB-231 (Figure 2B) and MCF-7 cells (Figure 2C). Next, we determined whether the genetic knockdown or chemical inhibition of SIRT2 affects the acetylation of the endogenous Prdx-1 in MCF-7 cells. Figure 2D demonstrates that chemical inhibition of the catalytic activity of SIRT2 by nicotinamide (NA) or shRNA-mediated 90% knock down of SIRT2 induced lysine acetylation of Prdx-1. We next performed the reverse immunoprecipitation with anti-acetylated lysine in cells with ectopic overexpression or knockdown of SIRT2. Figure 2E shows that ectopic overexpression of SIRT2 (shown above in Figure 2B) deacetylates Prdx-1, resulting in attenuated levels of the immunoprecipitated, acetylated Prdx-1. Conversely, SIRT2 knockdown caused an increase in the levels of the immunoprecipitated acetylated Prdx-1 (Figure 2E).

Figure 1. Knockdown (KD) of SIRT2 by shRNA induces acetylation of proteins including Peroxiredoxin-1.

A. HEK293 cells were stably transfected with control shRNA or SIRT2 shRNA constructs. Total cell lysates were prepared from the cell lines and immunoblot analyses were performed for SIRT2, acetylated α-tubulin, and α-tubulin. The expression levels of β-actin served as the loading control. B. Immunoblot analysis of total acetylated lysine in cell lysates from control shRNA or SIRT2 shRNA transfected HEK293 cells. C. S100 cytosolic extracts were prepared from HEK293 vector and SIRT2 knockdown cell lines and 2-D differential in-gel electrophoresis (DIGE) was performed. A representative 2D-gel image is presented. Protein spots exhibiting more than a two-fold difference in mobility in SIRT2-KD samples compared to vector control were identified by mass spectrometry. The arrows indicate the location of Peroxiredoxin 1 (Prdx-1), Malate Dehydrogenase (MDH) and Phosphoglycerate Kinase 1 (PGK1).

Figure 2. SIRT2 interacts with peroxiredoxin 1.

A. Cells lysates from HEK293 cells expressing FLAG tagged peroxiredoxin-1 (Prdx-1) and HA-tagged SIRT2 were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody. The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies. Total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analyses with anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies. B. MDA-MB-231 vector and FLAG-SIRT2 overexpressing cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody. Immunoblot analyses were performed for Prdx-1 and SIRT2 on the immunoprecipitates. Position of the IgG light chain (L.C.) is indicated with an arrow. C. MCF7 FLAG-SIRT2-overexpressing cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG M2 antibody-conjugated beads. Immunoblot analyses were performed for Prdx-1 and SIRT2 on the immunoprecipitates. Vertical lines indicate a repositioned gel lane. D. Cell lysates from MCF7 cells treated with 1mM of nicotinamide (NA) or transfected with SIRT2 shRNA were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Prdx-1 antibody. Immunoblot analysis was performed with anti-acetyl lysine and anti-Prdx-1 antibodies on the immunoprecipitates. Total cell lysates were also immunoblotted with anti-SIRT2, anti-Prdx-1 and β-Actin antibodies. Values underneath the blots indicate densitometry analysis. E. MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with vector, ectopic overexpression of SIRT2 or knockdown of SIRT2 were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-acetyl-lysine antibody. Immunoblot analysis was performed for Prdx-1 on the immunoprecipitates. Values underneath the blots indicate densitometry analysis.

Levels of SIRT2 affect Prdx-1 acetylation and its antioxidant activity

Next, we determined whether ectopic overexpression or activation of SIRT2 or knockdown of SIRT2 by shRNA perturbs acetylation of the endogenous Prdx-1. For this, we ectopically overexpressed or knocked-down SIRT2 by shRNA in MCF-7 and MB-231 cells (Figure 3A). We also ectopically expressed the catalytically inactive mutant form of SIRT2 (H187A), created by site-directed mutagenesis (10), in MB-231 cells (Figure 3A and 3B). First, we confirmed that the ectopic expression of SIRT2, but not of the mutant SIRT2, increased the intracellular lysine deacetylase activity in MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (Supplemental Figure S1 and data not shown). However, enforced alterations in the levels of SIRT2 neither affected the levels of Prdx-1, nor led to any change in the levels of several other HDACs, e.g., SIRT3, SIRT6 and HDAC6, or of the antioxidant proteins, including superoxide dismutase and catalase (Supplemental Figure 2A and data not shown). Ectopically expressed wild-type and mutant SIRT2 were localized to the cytoplasm of MB-231 and MCF7 cells (Figure 3B and Supplemental Figure 2B). As shown in Figure 3C, compared to the MB-231 transduced with the vector alone, by de-acetylating Prdx-1, ectopically overexpressed SIRT2 significantly inhibited the antioxidant activity of Prdx-1 (p = 0.01). Conversely, MB-231 cells exhibiting shRNA-mediated knockdown of SIRT2 showed a significant increase in the antioxidant activity of the resulting hyperacetylated Prdx-1 (Figure 3C). Here, the antioxidant activity of the de-acetylated or hyperacetylated Prdx-1 in the cellular protein extract was assayed by estimating its reducing effect on H2O2-mediated NADPH oxidation, which was compared to the antioxidant activity of the recombinant Prdx-1 in the same assay (Figure 3C). As compared to the control MB-231 (transduced with vector alone), treatment of MB-231 cells with ectopic overexpression of SIRT2 with 500 μM of H2O2, resulted in significantly increased intracellular levels of ROS (p = 0.01) (Figure 3D). Exposure to H2O2 caused over-oxidation of the active sulfhydryl residues in Prdx-1 to sulfinic or sulfonic acid, which was detected by utilizing the antibody that recognizes the over-oxidized cysteine in Prdx-1 (27), in MB-231 cells overexpressing wild-type SIRT2 but not those expressing the catalytically-dead mutant form of SIRT2 (Figure 3E). Following exposure of the MB-231 cells expressing the catalytically-dead mutant form of SIRT2 to H2O2, no increase in the levels of the oxidized Prdx-1 was observed (Figure 3E). Therefore, the reduced antioxidant activity of the de-acetylated Prdx-1 was associated with increased levels of ROS as well as increase in the oxidized form of Prdx-1, whereas the catalytically-dead mutant Prdx-1 was relatively resistant to oxidation. Collectively these findings highlight that, while the antioxidant activity of Prdx-1 regulates intracellular levels of H2O2, high levels of H2O2 in turn oxidize and regulate the antioxidant activity of Prdx-1 (15,16).

Figure 3. SIRT2 deacetylates Prdx-1 and decreases its activity.

A. MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells were stably transfected with vector or SIRT2 O/E and SIRT2 (H187A) mutant constructs or with control shRNA and SIRT2 shRNA constructs as indicated. Total cell lysates were prepared from the cell lines and immunoblot analyses were performed for the expression levels of SIRT2 and of β-actin. B. MDA-MB-231 overexpressing vector, SIRT2 or SIRT2 (H187A) mutant proteins were fixed, permeabilized and blocked with 3% BSA. The expression of FLAG was detected by immunofluorescent staining with FLAG M2 antibody followed by staining with Alexa 555-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Images were acquired using an LSM-510 Meta confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss) with a 63 X/1.2 NA oil immersion lens. C. Total lysates from MDA-MB-231 vector, SIRT2 O/E or SIRT2 KD cells were utilized to determine H2O2 reducing activity and the percentage change in Prdx-1 activity (NADPH oxidized/min/mg protein). Recombinant Prdx-1 (3 μg) was used as a positive control for the assay. D. MDA-MB-231 vector or SIRT2 O/E cells were grown in 96 well plates. The next day, the cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of hydrogen peroxide for 2 hours at 37°C. The media was aspirated and cells were washed with 1X PBS. DCF-DA (in phenol red free media) was added to the cells at a final concentration of 10 μM and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The excess dye was removed by washing with 1X PBS and the fluorescence was read at 485 nM using a BioTek plate reader. E. MDA-MB-231 vector, SIRT2 O/E and SIRT2 (H187A) mutant expressing cells were treated with H2O2 for 4 and 8 hours, as indicated. Following this, total cell lysates were prepared and immunoblot analyses were performed for oxidized-Prdx-1 and total Prdx-1. The expression levels of α-tubulin served as loading control.

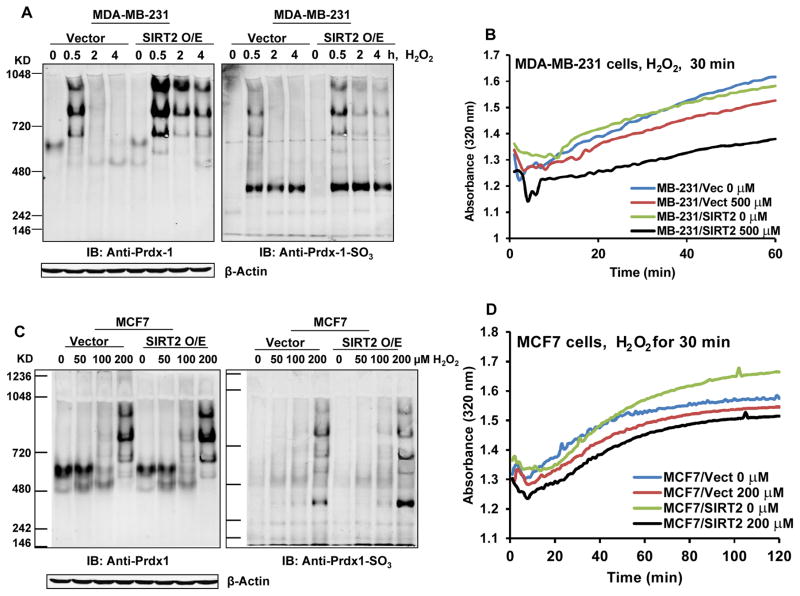

The cytosolic 2-Cys Prdx-1 has dual function as a peroxidase and molecular chaperone (18). Upon exposure to oxidative stress, Prdx-1 transitions to high molecular weight oligomers and functions as a molecular chaperone (31). Removal of the oxidative stress switches Prdx-1 back from a chaperone to a low molecular weight peroxidase function (18,31). Next, we determined whether in SIRT2 overexpressing cells expressing de-acetylated Prdx-1, the latter is over-oxidized due to increased intracellular levels of ROS, and whether Prdx-1 would form multimers and exhibit increased chaperone activity toward one of its known substrate proteins, malate dehydrogenase (MDH) (32). Figure 4A and Supplemental Figure S3 demonstrates that following exposure to 500 μM of H2O2 for 30 minutes to 4 hours, as compared to their respective controls, HEK293 and MB-231 cells overexpressing SIRT2 exhibited increased levels of the high molecular weight multimers of Prdx-1 and their oxidized counterparts (right and left panel), as detected by anti-Prdx-1 and anti-oxidized Prdx-1 antibody, respectively. Prx1 displays a robust capacity to suppress the misfolding of MDH. Thus, the increased chaperone function of the oxidized Prdx-1 multimers in SIRT2 overexpressing versus the vector control HEK293 and MB-231 cells exposed to H2O2 resulted in reduced absorbance at 320 nm (less light scattering of misfolded MDH), which was due to improved folding of MDH (Figure 4B). Similar effects were also observed in SIRT2-overexpressing MCF-7 versus the vector control cells exposed to lower concentrations of H2O2 for 30 minutes (Figure 4C and 4D).

Figure 4. SIRT2 overexpression increases the Prdx-1 chaperone activity in breast cancer cells following treatment with H2O2.

A. MDA-MB-231 vector or SIRT2 O/E cells were treated with 500 μM of hydrogen peroxide for 0–4 hours. At the end of treatment, the cells were lysed with native lysis buffer and separated on NuPAGE® 3–8% tris-acetate native gels to detect oligomers and multimers of peroxiredoxin-1 (A, left panel) and oxidized peroxiredoxin 1 (A, right panel). Cell lysates were also probed with anti-β-actin to confirm equal loading. B. MDA-MB-231 vector or SIRT2 O/E cells were treated with 500 μM of hydrogen peroxide for 30 minutes. Then, cell lysates (500 μg) were collected and peroxiredoxin-1 was immunoprecipitated by anti-Peroxiredoxin I (LF-MA0214, AbFrontier) and Dynabeads® M-280 sheep anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen). The immunoprecipitated peroxiredoxin-1 and Dynabeads were used for the chaperone activity assay. Each reaction contained 2 μM malate dehydrogenase (MDH) and the immunoprecipitated peroxiredoxin-1 with beads in 200 μL of 50 mM HEPES-KOH buffer (pH 7.5). The absorbance at 320 nm was monitored utilizing a BioTek SynergyMx plate reader at 43 °C for 2 hours. C. MCF7 vector and SIRT2 O/E cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of hydrogen peroxide for 30 minutes. At the end of treatment, the cells were lysed with native lysis buffer and separated on NuPAGE® 3–8% tris-acetate native gels to detect oligomers and multimers of peroxiredoxin-1 (C, left panel) and oxidized peroxiredoxin-1 (C, right panel). Cell lysates were also probed with anti- β-actin to confirm equal loading. D. MCF7 vector and SIRT2 O/E cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of hydrogen peroxide for 30 minutes. Cell lysates were collected as in (B) and absorbance at 320 nm was monitored utilizing a BioTek SynergyMx plate reader at 43 °C for 2 hours, as above.

Increased ROS and DNA damage is due to inactivation of Prdx-1 from SIRT2 mediated deacetylation

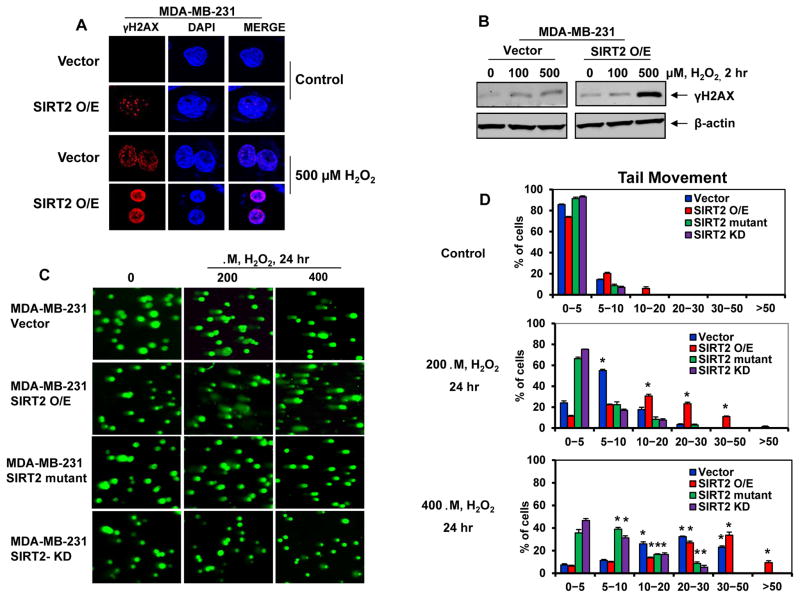

We next determined whether reduced antioxidant activity of Prdx-1 and higher intracellular ROS levels in the SIRT2 overexpressing cells would result in increased DNA damage, especially following exposure to H2O2. Figure 5A & 5B demonstrate that treatment with H2O2 induced higher intracellular levels of γ-H2AX, signifying an increase in the DNA damage and response, in the SIRT2 overexpressing versus the vector control MB-231 cells. This was estimated in the nuclei by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy, as well as in the cell lysates by immunoblot analysis (Figure 5A & 5B). We also determined the DNA damage and repair at an individual cell level by the Comet assay (19,20). Treatment with H2O2 induced more DNA damage, determined by estimating the length of the comet tails, in the SIRT2 overexpressing versus the vector control MB-231 cells (Figure 5C). Whereas a higher % untreated cells exhibited shorter comet tails and lower tail movement, treatment with H2O2 dose-dependently increased the % of cells with longer comet tails and higher tail movement, more so in the SIRT2 overexpressing versus the vector control MB-231 cells (Figure 5C & 5D). In contrast, exposure to H2O2 induced less DNA damage represented by higher % of cells with shorter tail movement in MB-231 cells expressing either the catalytically dead mutant SIRT2 or knockdown of SIRT2 (Figure 5C & 5D).

Figure 5. SIRT2 increases DNA damage on H2O2 exposure.

A. MDA-MB-231 vector or SIRT2 O/E cells were plated in chamber slides overnight at 37°C. The following day, cells were treated with or without 500 μM of H2O2 for 4 hours. After treatment, the cells were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked with 3% BSA. The expression of γH2AX was detected by immunofluorescent staining (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. B. MDA-MB-231 vector or SIRT2 O/E cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of H2O2 for 2 hours. Following this, total cell lysates were immunoblotted for γH2AX and β-actin. C. MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing SIRT2, SIRT2 (H187A) mutant or SIRT2 KD were treated with the indicated concentration of H2O2 for 24 hours and comet assay was performed. D. Quantitative tail movement of each indicated concentration in the MDA-MB-231 cells is presented. * indicates values significantly greater in cells treated with hydrogen peroxide than untreated control cells (p< 0.05).

FOXO3A and BIM involvement in increased cell death due to oxidative stress in SIRT2-ovreexpressing breast cancer cells

Previous studies have demonstrated that increased intracellular ROS levels induce the nuclear localization and transcriptional activity of FOXO3A, resulting in up regulation of one of its targets, the pro-apoptotic, BH3 domain-only BIM protein (10,11). Consistent with this, as compared to the untreated control cells, MB-231 cells overexpressing SIRT2 demonstrated higher accumulation of FOXO3A in the nucleus (Figure 6A and 6B). Treatment with H2O2 further increased the levels of FOXO3A in the nucleus of SIRT2 O/E cells to a greater degree than in the vector control cells. Similar results were also obtained in MCF7 cells following ectopic overexpression of SIRT2 (Supplemental Figure S4A). This was associated with more induction of BIM levels and increased caspase-3 cleavage and activity (Supplemental Figure S4B). In a dose- and time-dependent manner, treatment with H2O2 also induced markedly higher levels of cell death in MB-231 cells overexpressing SIRT2, associated with de-acetylated and relatively inactive Prdx-1, as compared to a similar treatment with H2O2 of MB-231 cells expressing catalytically inactive mutant SIRT2 or those with knockdown of SIRT2 (Figure 6C). Next, we compared the lethal effects of exposure to the intracellular ROS-inducing agents, such as arsenic trioxide (AT) and menadione, in MB-231 and MCF-7 cells with the ectopic overexpression of SIRT2 versus the control MB-231 and MCF-7 cells with the ectopic expression of the vector alone. As shown in Figure 6D and 6E, exposure to AT or menadione induced significantly more lethality in cells with overexpression of SIRT2 versus the control MB-231 and MCF-7 cells.

Figure 6. SIRT2 overexpression induces cell death in breast cancer cells.

A. MDA-MB231 vector and SIRT2 O/E cells were exposed to the indicated concentration of H2O2 for 4 hours, fixed, permeabilized and stained for FOXO3a. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Confocal immunofluorescent microscopy was performed using LSM 510Meta microscope (Zeiss) using a 63X/1.2 NA oil immersion lens. B. Quantification of mean fluorescent intensity of nuclear FOXO3A in MDA-MB-231 vector and SIRT2 O/E cells with or without treatment with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for 4 hours. * indicate values significantly different in SIRT2 overexpressing cells with or without H2O2 treatment : * = P <0.05; ** = P <0.005; *** =P <0.0005; **** = P <0.0001. C. MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing SIRT2 were treated with indicated concentrations of H2O2 for 48 hours (top panel), or with 500 μM of H2O2 for indicated times (bottom panel). The percentages of propidium iodide (PI)-positive, non-viable cells were determined by flow cytometry. D. MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells overexpressing SIRT2 and vector control were treated with the indicated concentrations of arsenic trioxide for 48 hours. At the end of treatment, the percentages of PI-positive, non-viable cells were determined by flow cytometry. E. MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 vector and SIRT2 O/E cells were treated with menadione as indicated for 48 hours. Following this, the percentage of PI-positive, non-viable cells, in each condition was determined by flow cytometry.

Knockdown of SIRT2 reduces hydrogen peroxide-mediated embryonic toxicity and cardiac abnormalities in zebrafish embryos

Previous reports have documented that embryonic toxicity due to oxidative stress induced by H2O2 or AT treatment of developing embryos of zebrafish (Danio rerio) is characterized by in vivo developmental abnormalities, including pericardial edema, circulation failure, looping failure and dorsal curvature (29). Next, we determined the effects of anti-sense morpholinos against exon 6 of the zebrafish homologue of SIRT2 or mismatch controls, injected into single cell stage zebrafish embryos (29). The effects of the morpholinos on mRNA level of SIRT2 and the effect of treatment with 3.0 mM of H2O2 for 30 minutes on ROS levels at 48 hours post-fertilization (hpf) were determined (Supplemental Figure S5). Figure 7A demonstrates that compared to the mismatch control morpholino, anti-sense SIRT2 morpholino down modulated mRNA levels of SIRT2. Treatment with H2O2 induced ROS levels in control embryos exposed to 3.0 mM H2O2, which was markedly suppressed by co-treatment with the anti-oxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (Figure 7B). In contrast, SIRT2 morpholino treatment significantly attenuated ROS levels due to H2O2 treatment, which was further reduced by co-treatment with NAC (Figure 7B). Notably, injection of the mismatch control morpholino, followed by exposure to 3.0 mM H2O2, showed the characteristic toxicity profile, including pericardial edema, circulation failure and dorsal curvature in zebrafish larvae at 120-hpf. However, consistent with the attenuation of ROS levels, SIRT2 morpholino-treated embryos failed to exhibit developmental abnormalities including pericardial edema and dorsal curvature (Figure 7C). These findings demonstrate that even a partial knockdown of SIRT2, by inducing acetylation and increased antioxidant activity of Prdx-1, abrogated the ROS-mediated toxic effects in zebrafish embryos.

Figure 7. Knockdown of SIRT2 in the zebrafish embryos decreased H2O2-induced ROS levels and abrogated ROS-mediated cardiac edema and abnormal body curvature.

A. The splice-blocking MO targeting against exon 6 (coding for the small domain of SIRT2) of zebrafish SIRT2 was injected into single-cell stage zebrafish embryos, and expression of SIRT2 mRNA was assessed from the embryos, after 48 hours, by qPCR. B. Control and MO treated embryos were exposed to 3 mM of hydrogen peroxide at 48-hpf with or without N-acetyl cysteine (NAC). ROS levels in the embryos were monitored at 30 min using DCF-DA. C. The morphological changes at day 5 (after hydrogen peroxide treatment, 168-hpf) were imaged. D. Schematic model for the activity of increased SIRT2 in breast cancer cells. Induction of SIRT2 decreases the antioxidant activity of Prdx-1, leading to oxidation of Prdx-1 and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS). This induces the transient induction of Prdx-1 multimers and increased Prdx-1 chaperone activity. The ROS that are generated induce the translocation of FOXO3A into the nucleus where it can activate the transcription of pro-apoptotic BIM. The ROS can also directly induce DNA damage, leading to increased cell death.

DISCUSSION

Previous reports have identified the role of SIRT2 as a tumor suppressor, primarily due to its ability to maintain genomic fidelity during mitosis (1,5,6). SIRT2 achieves this by deacetylating and stabilizing BUBR1 and APC/C activity, which delays anaphase until chromosomes are attached at the mitotic spindle (1,5,6,33). Recently, SIRT2 was also shown to directly interact with β-catenin and inhibit the WNT transcriptional targets including the oncoproteins survivin, c-Myc and cyclin D1 (34). SIRT2 is located at 19q13.2, which is frequently deleted in human gliomas (35). Consistent with these observations, SIRT2 knockout mice develop cancers, and SIRT2 levels are reduced in variety of cancer types, including breast, liver, renal and prostate cancers (1,5). Along with SIRT2, the peroxide scavenger 2-Cys Prdx-1 has also been shown to have a tumor suppressive role and is classified as a ‘gerontogene’ (36). Mice lacking Prdx-1 develop tumors prematurely during aging, associated with increased 8-oxo-dG levels and oxidative DNA damage (37). Prdx-1 deficiency was also shown to cause increased c-Myc and AKT activity, the latter due to ROS mediated inactivation of PTEN (38–40). Additionally, Prdx-1 was also demonstrated to inhibit TNFα-mediated NFkB transcriptional activity (16). In the present studies, we have established for the first time a direct link between SIRT2 levels and Prdx-1 deacetylation and activity. Utilizing DIGE coupled with MS/MS, we demonstrate that the predominantly cytosolic SIRT2 binds and de-acetylates cytosolic Prdx-1. This is consistent with the previous reports, indicating that Prdx-1 present in the inter-mitochondrial space is de-acetylated on lysine-197 by the mitochondria-resident SIRT3, whereas the cytosolic Prdx-1 is also a substrate for deacetylation by HDAC6 (41,42). Importantly, we demonstrate here that SIRT2 mediated de-acetylation of Prdx-1 reduces its antioxidant peroxidase activity (Figure 7D). Consequently, SIRT2 overexpressing breast cancer cells, especially when subjected to oxidant stress induced by H2O2, accumulate ROS and DNA damage, as estimated by the comet assay and increased γH2AX levels, as well as demonstrate loss of cell viability. In contrast, this was not seen in breast cancer cells with ectopic expression of the catalytically-inactive mutant form of SIRT2. Reduced peroxidase activity of the de-acetylated Prdx-1 was also associated with ROS-induced over-oxidation and multimer formation by Prdx-1, which represents a switch from the peroxidase to chaperone function of Prdx-1 (15,18,27). Previous studies have shown that the chaperone function of multimeric Prdx-1 enhances resistance to the lethal effects of oxidative stress and heat shock (18,27). Despite this, our findings also show that the ultimate loss of viability caused by exposure of the SIRT2 overexpressing cells to high levels of H2O2 was due to increased nuclear accumulation of FOXO3A accompanied with the induction of BIM levels (Figure 7D). This is also consistent with the tumor suppressor function of SIRT2.

Compared to their normal counterparts, cancer cells exhibit increased levels of ROS, including superoxide and hydroxyl radicals and H2O2, which promotes cell signaling for proliferation and other biologic functions (13,16,30,43). Engagement by the ligands or cytokines of receptor tyrosine kinases or G protein coupled receptors leads to transient generation of H2O2, catalyzed by the cell membrane-localized NADPH oxidases (16,30,43). This H2O2 oxidizes and inactivates cysteine residue in the nearby tyrosine phosphatases, which normally attenuate receptor signaling by dephosphorylating the pathway-signaling kinases, thereby promoting the signaling for growth and proliferation (16,17,30,43). Recently, membrane-associated Prdx-1 was shown to be transiently phosphorylated on its tyrosine-194 residue and thereby inactivated, allowing nearby accumulation of H2O2, inactivation of tyrosine phosphatases and stimulation of the kinase mediated signaling (30). However, excessive levels of ROS can inflict oxidative damage to lipids, proteins and DNA (13). Among the H2O2 neutralizing proteins is Prdx-1, possessing a conserved N-terminal cysteine residue, which is also oxidized by H2O2 but reduced by thioredoxin (16,43). Findings presented here clearly demonstrate that knockdown of SIRT2, by inducing acetylation of Prdx-1, increases its antioxidant peroxidase activity. This was associated with a reduction in the DNA damage and apoptosis triggered by H2O2-induced oxidant stress.

In contrast to its tumor suppressive role during tumorigenesis, in a variety of established tumor types, Prdx-1 levels are increased and have been shown to be transcriptionally up regulated by NRF2 (37,39,44). Increased Prdx-1 levels have been demonstrated in many cancers, including bladder cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), where they have been associated with a high grade and advanced stages (36,45,46). Additionally, Prdx-1 has been demonstrated to potentially serve as a prognostic and therapeutic target in cancer (47,48). Overall, these reports highlight that Prdx-1 levels and activity regulate the redox homeostasis, which controls the growth and survival of cancer cells (13). Findings presented here clearly demonstrate that knockdown of SIRT2, by inducing acetylation of Prdx-1, increases its antioxidant peroxidase activity. This was accompanied by decreased in vitro accumulation of DNA damage detected by the comet assay, following exposure to oxidative stress induced either by H2O2 or by exposure to AT or menadione. Furthermore, in vivo SIRT2 knockdown also exerted protection against toxicity associated with oxidative stress in zebrafish embryos. There was a reduction in the H2O2-induced accumulation of ROS and the embryos also failed to develop characteristic features of embryonic toxicity due to oxidative stress.

In summary our findings demonstrate that, in cancer cells, selectively activating SIRT2 would lead to deacetylation and inactivation of Prdx-1, thereby sensitizing cancer cells to agents that induce oxidative stress and promote lethal DNA damage. By inducing nuclear accumulation of FOXO3A and induction of BIM, increased SIRT2 with reduced Prdx-1 activities could also induce lethal effects through a mechanism independent of the function of the tumor suppressor TP53.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This research was partially supported by the CCSG P30 CA016672.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Chalkiadaki A, Guarente L. The multifaceted functions of sirtuins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:608–24. doi: 10.1038/nrc3985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.North BJ, Marshall BL, Borra MT, Denu JM, Verdin E. The human Sir2 ortholog, SIRT2, is an NAD+-dependent tubulin deacetylase. Mol Cell. 2003;11:437–44. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders BD, Jackson B, Marmorstein R. Structural basis for sirtuin function: What we know and what we don’t. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:1604–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaquero A, Scher B, Lee DH. SirT2 is a histone deacetylase with preference for histone H4 Lys 16 during mitosis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1256–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.1412706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HS, Vassilopoulos A, Wang RH, Lahusen T, Xiao Z, Xu X, et al. SIRT2 maintains genome integrity and suppresses tumorigenesis through regulating APC/C activity. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.North BJ, Rosenberg MA, Jeganathan KB, Hafner AV, Michan S, Dai J, et al. SIRT2 induces the checkpoint kinase BubR1 to increase lifespan. EMBO J. 2014;33:1438–53. doi: 10.15252/embj.201386907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang YP, Zhou LS, Zhao YZ, Wang SW, Chen LL, Liu LX, et al. Regulation of G6PD acetylation by SIRT2 and KAT9 modulates NADPH homeostasis and cell survival during oxidative stress. EMBO J. 2014;33:1304–1320. doi: 10.1002/embj.201387224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu Y, Li F, Lv L, Li T, Zhou X, Deng CX, et al. Oxidative stress activates SIRT2 to deacetylate and stimulate phosphoglycerate mutase. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3630–3642. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin R, Tao R, Gao X, Li T, Zhou X, Guan KL, et al. Acetylation stabilizes ATP-citrate lyase to promote lipid biosynthesis and tumor growth. Mol Cell. 2013;51:506–18. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang F, Nguyen M, Qin XF, Tong Q. SIRT2 deacetylates FOXO3a in response to oxidative stress and caloric restriction. Aging Cell. 2007;6:505–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam EW, Brosens JJ, Gomes AR, Koo CY. Forkhead box proteins: tuning forks for transcriptional harmony. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:482–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc3539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narayan N, Lee IH, Borenstein R, Sun J, Wong R, Tong G, et al. The NAD-dependent deacetylase SIRT2 is required for programmed necrosis. Nature. 2012;492:199–204. doi: 10.1038/nature11700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:579–91. doi: 10.1038/nrd2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bindoli A, Fukuto JM, Forman HJ. Thiol chemistry in peroxidase catalysis and redox signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1549–64. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood ZA, Schroder E, Robin Harris J, Poole LB. Structure, mechanism and regulation of peroxiredoxins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:32–40. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang SW, Rhee SG, Chang TS, Jeong W, Choi MH. 2-Cys peroxiredoxin function in intracellular signal transduction: therapeutic implications. Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:571–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Immenschuh S, Baumgart-Vogt E. Peroxiredoxins, oxidative stress, and cell proliferation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:768–77. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jang HH, Lee KO, Chi YH, Jung BG, Park SK, Park JH, et al. Two enzymes in one; two yeast peroxiredoxins display oxidative stress-dependent switching from a peroxidase to a molecular chaperone function. Cell. 2004;117:625–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ha K, Fiskus W, Choi DS, Bhaskara S, Cerchietti L, Devaraj SG, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitor treatment induces ‘BRCAness’ and synergistic lethality with PARP inhibitor and cisplatin against human triple negative breast cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2014;5:5637–50. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ha K, Fiskus W, Rao R, Balusu R, Venkannagari S, Nalabothula NR, et al. Hsp90 inhibitor-mediated disruption of chaperone association of ATR with hsp90 sensitizes cancer cells to DNA damage. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1194–206. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiskus W, Sharma S, Qi J, Valenta JA, Schaub LJ, Shah B, et al. Highly active combination of BRD4 antagonist and histone deacetylase inhibitor against human acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:1142–54. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiskus W, Saba N, Shen M, Ghias M, Liu J, Gupta SD, et al. Auranofin induces lethal oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress and exerts potent preclinical activity against chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2520–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JA, Park S, Kim K, Rhee SG, Kang SW. Activity assay of mammalian 2-cys peroxiredoxins using yeast thioredoxin reductase system. Anal Biochem. 2005;338:216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y, Rao R, Shen J, Tang Y, Fiskus W, Nechtman J, et al. Role of acetylation and extracellular location of heat shock protein 90alpha in tumor cell invasion. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4833–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poli G, Ceni E, Armignacco R, Ercolino T, Canu L, Baroni G, et al. 2D-DIGE proteomic analysis identifies new potential therapeutic targets for adrenocortical carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:5695–706. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moon JC, Hah YS, Kim WY, Jung BG, Jang HH, Lee JR, et al. Oxidative stress-dependent structural and functional switching of a human 2-Cys peroxiredoxin isotype II that enhances HeLa cell resistance to H2O2-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28775–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rabilloud T, Heller M, Gasnier F, Luche S, Rey C, Aebersold R, et al. Proteomics analysis of cellular response to oxidative stress. Evidence for in vivo overoxidation of peroxiredoxins at their active site. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19396–401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106585200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker SL, Ariga J, Mathias JR, Coothankandaswamy V, Xie X, Distel M, et al. Automated reporter quantification in vivo: high-throughput screening method for reporter-based assays in zebrafish. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, Ma Y, Li D, Gao X, Li P, Bai N, et al. Arsenic impairs embryo development via down-regulating Dvr1 expression in zebrafish. Toxicol Lett. 2012;212:161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woo HA, Yim SH, Shin DH, Kang D, Yu DY, Rhee SG. Inactivation of peroxiredoxin I by phosphorylation allows localized H(2)O(2) accumulation for cell signaling. Cell. 2010;140:517–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumsta C, Jakob U. Redox-regulated chaperones. Biochem. 2009;48:4666–76. doi: 10.1021/bi9003556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee W, Choi KS, Riddell J, Ip C, Ghosh D, Park JH, et al. Human peroxiredoxin 1 and 2 are not duplicate proteins: the unique presence of CYS83 in Prx1 underscores the structural and functional differences between Prx1 and Prx2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22011–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610330200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sebastian C, Satterstrom FK, Haigis MC, Mostoslavsky R. From sirtuin biology to human diseases: an update. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:42444–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.402768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen P, Lee S, Lorang-Leins D, Trepel J, Smart DK. SIRT2 interacts with beta-catenin to inhibit Wnt signaling output in response to radiation-induced stress. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12:1244–53. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0223-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hiratsuka M, Inoue T, Toda T, Kimura N, Shirayoshi Y, Kamitani H, et al. Proteomics-based identification of differentially expressed genes in human gliomas: down-regulation of SIRT2 gene. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2003;309:558–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nystrom T, Yang J, Molin M. Peroxiredoxins, gerontogenes linking aging to genome instability and cancer. Genes Dev. 2012;26:2001–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.200006.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neumann CA, Krause DS, Carman CV, Das S, Dubey DP, Abraham JL, et al. Essential role for the peroxiredoxin Prdx1 in erythrocyte antioxidant defence and tumour suppression. Nature. 2003;424:561–5. doi: 10.1038/nature01819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Egler RA, Fernandes E, Rothermund K, Sereika S, de Souza-Pinto N, Jaruga P, et al. Regulation of reactive oxygen species, DNA damage, and c-Myc function by peroxiredoxin 1. Oncogene. 2005;24:8038–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao J, Schulte J, Knight A, Leslie NR, Zagozdzon A, Bronson R, et al. Prdx1 inhibits tumorigenesis via regulating PTEN/AKT activity. EMBO J. 2009;28:1505–17. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neumann CA, Fang Q. Are peroxiredoxins tumor suppressors? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:375–80. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rauh D, Fischer F, Gertz M, Lakshminarasimhan M, Bergbrede T, Aladini F, et al. An acetylome peptide microarray reveals specificities and deacetylation substrates for all human sirtuin isoforms. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2327. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parmigiani RB1, Xu WS, Venta-Perez G, Erdjument-Bromage H, Yaneva M, Tempst P, et al. HDAC6 is a specific deacetylase of peroxiredoxins and is involved in redox regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9633–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803749105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hole PS, Darley RL, Tonks A. Do reactive oxygen species play a role in myeloid leukemias? Blood. 2011;117:5816–26. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-326025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim YJ, Ahn JY, Liang P, Ip C, Zhang Y, Park YM. Human prx1 gene is a target of Nrf2 and is up-regulated by hypoxia/reoxygenation: implication to tumor biology. Cancer Res. 2007;67:546–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alfonso P, Catala M, Rico-Morales ML, Durante-Rodriguez G, Moro-Rodriguez E, Fernandez-Garcia H, et al. Proteomic analysis of lung biopsies: Differential protein expression profile between peritumoral and tumoral tissue. Proteomics. 2004;4:442–7. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quan C, Cha EJ, Lee HL, Han KH, Lee KM, Kim WJ. Enhanced expression of peroxiredoxin I and VI correlates with development, recurrence and progression of human bladder cancer. J Urology. 2006;175:1512–6. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00659-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen MF, Keng PC, Shau H, Wu CT, Hu YC, Liao SK, et al. Inhibition of lung tumor growth and augmentation of radiosensitivity by decreasing peroxiredoxin I expression. Int J Radiation Oncol Biol, Phys. 2006;64:581–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim JH, Bogner PN, Baek SH, Ramnath N, Liang P, Kim HR, et al. Up-regulation of peroxiredoxin 1 in lung cancer and its implication as a prognostic and therapeutic target. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2326–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.