Abstract

Molecular components of store-operated calcium entry have been identified in the recent past and consist of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane-resident calcium sensor STIM and the plasma membrane-localized calcium channel Orai. The physiological function of STIM and Orai is best defined in vertebrate immune cells. However, genetic studies with RNAi strains in Drosophila suggest a role in neuronal development and function. We generated a CRISPR-Cas-mediated deletion for the gene encoding STIM in Drosophila (dSTIM), which we demonstrate is larval lethal. To study STIM function in neurons, we merged the CRISPR-Cas9 method with the UAS-GAL4 system to generate either tissue- or cell type-specific inducible STIM knockouts (KOs). Our data identify an essential role for STIM in larval dopaminergic cells. The molecular basis for this cell-specific requirement needs further investigation.

Keywords: null allele, Orai, SOCE, tyrosine hydroxylase, hypoderm

The signaling properties of intracellular Ca2+ stores evolved in metazoans and plant cells where they regulate multiple biological processes including secretion, gene transcription, enzymatic activity, and motility (Prakriya and Lewis 2015). A range of external stimuli including hormones, neuromodulatory chemicals, and sensory signals activate their cognate membrane receptors resulting in cleavage of phosphatidyl inositol 1, 4 bisphosphate (PIP2) to generate inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), which in turn binds to an intracellular ligand-gated Ca2+ channel, the IP3 receptor (IP3R), present on ER Ca2+ store membranes (Patel et al. 1999; Clapham 2007). Release of ER Ca2+ through the IP3R generates transient cellular Ca2+ signals and simultaneously depletes intracellular Ca2+ stores. The drop in ER Ca2+ is sensed by ER membrane-localized STIM molecules through their Ca2+-binding EF hand motifs, leading to their clustering and rearrangement of the ER membrane with movement of the STIM clusters toward ER-PM junctions, where the physical interaction of STIM with the store-operated Ca2+ channel, Orai, results in extracellular Ca2+ entry generally referred to as store-operated Ca2+ entry or SOCE (Liou et al. 2007; Stiber et al. 2008). Unlike, the transient nature of Ca2+ release through the IP3R, SOCE can be sustained over minutes and hours and is likely to have significant and wide-ranging effects on organismal physiology and perhaps development. The kinetics of SOCE-derived cytosolic calcium signals are determined by the activity of a range of ionic exchangers, channels, and pumps, significant among which is the sarco-endoplasmic reticular Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) pump (Sanyal et al. 2006; Venkiteswaran and Hasan 2009; Hasan and Venkiteswaran 2010; Brini et al. 2014).

For a better understanding of the role of SOCE during development and in organismal physiology, genetic studies of the key SOCE components STIM and Orai are required. Vertebrate studies have demonstrated that STIM1, STIM2, and Orai1 KO mice are lethal (Baba et al. 2008; Gwack et al. 2008; Oh-Hora et al. 2008; Stiber et al. 2008; Beyersdorf et al. 2009), supporting an essential requirement for SOCE during vertebrate development. However, the underlying causes of lethality are not clearly understood. Unlike vertebrates, single genes encode the SOCE components dSTIM (CG9126) and dOrai (CG11430) in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster (Roos et al. 2005; Cai 2007). The study of Drosophila dSTIM and dOrai mutants can, thus, generate vital information about the nature of physiological and developmental processes regulated by SOCE. A hypomorphic allele of dOrai, orai3, has been studied previously for phagocytic function (Cuttell et al. 2008) and flight circuit development (Pathak et al. 2015), and has been described as partially lethal. However, mutants for dSTIM have not been characterized. Here, we have generated a complete KO as well as a tissue-specific Cas9-inducible UAS construct targeting the complete dSTIM open reading frame, using a modified CRISPR-Cas technique (Jinek et al. 2012; Cong et al. 2013; Mali et al. 2013). The inducible mutant strain allowed the investigation of multiple cell types and their individual contribution to the phenotype of the complete dSTIM KO. Surprisingly, lethality of dSTIM KO larvae was mirrored by inducing dSTIM mutations in cells expressing the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), which include dopaminergic neurons and hypoderm cells.

Materials and Methods

Fly rearing and stocks

Drosophila strains were grown in standard corn flour agar media supplemented with yeast. All Drosophila strains were grown at 25°, unless specified in the text. Canton-S was used as the wild-type (WT) Drosophila strain. The ubiquitous GAL4 strain, Actin5cGAL4 (BL4414); pan-neuronal drivers ElavC155GAL4 (BL458) and nSybGAL4 (BL51635); a muscle-specific GAL4, Dmef2 (BL27390); a glutamatergic neuron GAL4, OK371 (BL26160); and the orai3 mutant strains (BL17538) were obtained from BDSC (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, Bloomington, IN). A peptidergic neuron GAL4, c929, was kindly gifted by P. H. Taghert, Washington University (Hewes et al. 2003). The THGAL4 strain was a kind gift of S. Birman and has been described earlier (Friggi-Grelin et al. 2003). The UASdOrai (referred to as dOrai) and UASdSTIM (referred to as dSTIM) strains were generated by cloning of the publicly available full-length cDNA (RE30427) of dOrai and (BDGP LD45776) dSTIM (Venkiteswaran and Hasan 2009; Agrawal et al. 2010), followed by microinjection to obtain transgenic fly strains. The THA-GAL4 strain was kindly provided by M. Wu, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore (Liu et al. 2012). The UASCas9 strain (BL54593) was obtained from BDSC.

Molecular cloning

Single guide (sgRNA) targets were designed at the 5′- and 3′-end of the STIM open reading frame (5′-sgRNA-dSTIM AATGCGAAAGAATACCATTTGG; 3′-sgRNA-dSTIM GGATGACTGAAGAACCTCTTGG). The sgRNAs were cloned in the pU6-Bbs1-chiRNA vector as previously described (Gratz et al. 2013). To make the dual-sgRNA constructs, the same two sgRNAs were cloned in pBFv6.2 and pBFv6.2B vectors, respectively, and then a dual-sgRNA construct was generated as described by Kondo and Ueda (2013).

Generation of dual-sgRNA transgenic flies

Dual-sgRNA was integrated into the attP40 landing site on the second chromosome by phiC31 integrase using the y1 v1 nos-phiC31; attP40 host (Bischof et al. 2007). Surviving G0 flies were intercrossed and the progeny was screened for the v+ eye marker. A single transformant was mated to y1, v1; Tft/CyO flies. Offspring in which the transgene was balanced were collected to establish a stock.

Generation of STIM KO

A total of 310 w1118 embryos were injected with a mixture of plasmids encoding hsp70-Cas9 (Gratz et al. 2013) (500 ng/μl), 5′-sgRNA-STIM (150 ng/μl), and 3′-sgRNA-STIM (150 ng/μl). Seventy-two F0 adults that emerged were individually crossed with FM7a balancer flies. After 1 wk of egg laying, the parent F0 flies were individually squished in squishing buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, 25 mM NaCl, and 200 g/ml Proteinase K) and were screened for deletion by PCR using the following primers: del-STIM-F, 5′-CTATGACTTTCGCGAGCAAC-3′ and del-STIM-R, 5′-CATCCGTTCCCTTCAGTTGT-3′.

Among the F0 flies, 17 individuals were identified as founders for the genomic deletion. A total of 198 F1 progeny obtained from these 17 founder lines were individually crossed to FM7a balancers. These were individually tested for deletion of the dSTIM locus by PCR using the primers mentioned above. Among these, two lines tested positive for deletion by PCR and were confirmed by sequencing of the PCR product. These heterozygous balanced flies were collected to establish a stock. Only one of the two lines was fertile and could be propagated further.

Staging

Staging experiments were performed to obtain lethality profiles of the indicated genotypes as described previously (Joshi et al. 2004). Timed and synchronized egg laying was done for 6 hr at 25°. The larvae were collected at 60–66 hr after egg laying (AEL) in batches of 25 staged larvae. Each batch of 25 larvae was placed in a separate vial and minimally three vials containing agar-less media were tested for every genotype at each time point. Larvae were grown at 25°. Heteroallelic and heterozygous larvae were identified using dominant markers (FM7iGFP, TM6Tb, and CyoGFP). The larvae were screened at the indicated time points for number of survivors and stage of development, determined by the morphology of the anterior spiracles (Ashburner 1989). Experiments to determine the viability of experimental genotypes and their corresponding genetic controls were performed simultaneously in all cases.

Data analysis and statistics

The size of third instar larvae was measured using Image J 1.50i (Wayne Rasband; Java 1.8.0_77). Size calibration was performed with a hemocytometer and sizes of third instar larvae were measured at the indicated times (AEL). Significant differences (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001) between data were tested by a Student’s t-test. Unless specified, all comparisons were to the WT. For larval staging experiments, significant differences were tested by Student’s t-test. The genotypes that were compared and the P-values obtained are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Comparison of number of second instar larvae at 80–86 hr and adults at 320–326 hr.

| Figure | Genotype | Compared to | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 2B | STIMko | STIMko/+ | < 0.001 |

| nSyb > STIMko rescue | STIMko | NS | |

| Figure 2C | orai3 | WT | < 0.001 |

| ElavC155 > dOrai; orai3 | orai3 | < 0.001 | |

| Figure 2E | STIMko/+orai3/+ | orai3/+ | < 0.05 |

| Figure 3E | ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual | cas9;STIMdual | < 0.05 |

| ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual rescue | ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual | < 0.05 | |

| Figure 4C | TH > cas9;STIMdual | TH/+ | < 0.001 |

| THA > cas9;STIMdual | THA/+ | < 0.05 | |

| TH > cas9;STIMdual rescue | TH > cas9;STIMdual | < 0.05 | |

| Figure 4D | STIMko | STIMko/+;dSTIM/+ | < 0.001 |

| TH > STIMko;dSTIM | STIMko | < 0.001 | |

| Figure 4E | STIMko | THA/+ | < 0.001 |

| THA > STIMko;dSTIM | STIMko | < 0.001 | |

| Figure S4A | orai3 | TH/+ | < 0.001 |

| TH > dOrai;orai3 | orai3 | < 0.05 | |

| Figure S4B | orai3 | OK371/+ | < 0.05 and < 0.001 |

| OK371 > dOrai;orai3 | orai3 | < 0.05 | |

| Figure S4C | orai3 | c929/+ | < 0.05 and < 0.001 |

| c929 > dOrai;orai3 | orai3 | < 0.05 | |

| Figure S4D | orai3 | dMef2/+ | < 0.05 and < 0.001 |

| Dmef2 > dOrai;orai3 | orai3 | < 0.05 |

NS, not significant; WT, wild-type; TH, tyrosine hydrolase.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining of larval Drosophila brains was performed according to a published protocol for adult brains (Sadaf et al. 2015). The following primary antibodies were used at the indicated dilutions: anti-GFP antibody (1:10,000; A6455 Life Technologies) and Mouse anti-TH antibody (1:40; Immunostar). Secondary antibodies used were anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (#A1108, Life Technologies) and anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 568 (#A1104, Life Technologies) at a dilution of 1:400. Confocal images were obtained using an Olympus Confocal Microscope FV1000. Image visualization and analysis was performed using a FV10 ASW 4.2 viewer.

RNA isolation and q-PCR

The method of RNA isolation and q-PCR was the same as described previously (Pathak et al. 2015), using the following primers: rp49 Forward, 5′-CGGATCGATATGCTAAGCTGT-3′; rp49 Reverse, 5′-GCGCTTGTTCGATCCGTA-3′; dSTIM Forward, 5′-GAAGCAATGGATGTGGTTCTG-3′; and dSTIM Reverse 5′-CCGAGTTCGATGAACTGAGAG-3′.

Western blots

Larval or adult CNS of appropriate genotypes were dissected in cold PBS. Between 5 and 10 brains were homogenized in 50 µl of homogenizing buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5% Glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 1% Triton X-100, and 1 mM PMSF) and 10–15 µl of the homogenate was run on an 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. The protein was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by standard protocols and the membrane was incubated in the primary antibody overnight at 4°. Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: two mouse anti-dSTIM antibodies 8G1 and 3C1 (generated by Bioneeds, Bangalore, India) mixed at 1:1 and used at 1:20 dilution, and anti-β-tubulin monoclonal (E7, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa) at 1:5000. Secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase was used at a dilution of 1:3000 (anti-mouse HRP; Cell Signaling 7076S). The protein was detected on the blot by a chemiluminescent detection solution from Thermo Scientific (No. 34075; Rockford, IL).

Data availability

There are six supplemental files associated with this manuscript. Data in these supplemental files supports the results of the main figures and text. Supplemental material File S1 contains the detailed figure legends for all the Supplemental figures. Figure S1 contains supporting data for Figure 1 with the results of PCR screening for identifying putative STIMko strains. Figure S2 has genetic controls for the data with orai3 mutants and STIMko presented in Figure 2. Figure S3 contains supporting data and genetic controls for Figure 3. Genetic controls and data supporting a role for dOrai in larval dopaminergic neurons is shown in Figure S4, whereas further data supporting a role of dSTIM in larval dopaminergic neurons is presented in Figure S5. Both Figure S4 and Figure S5 support the results presented in Figure 4.

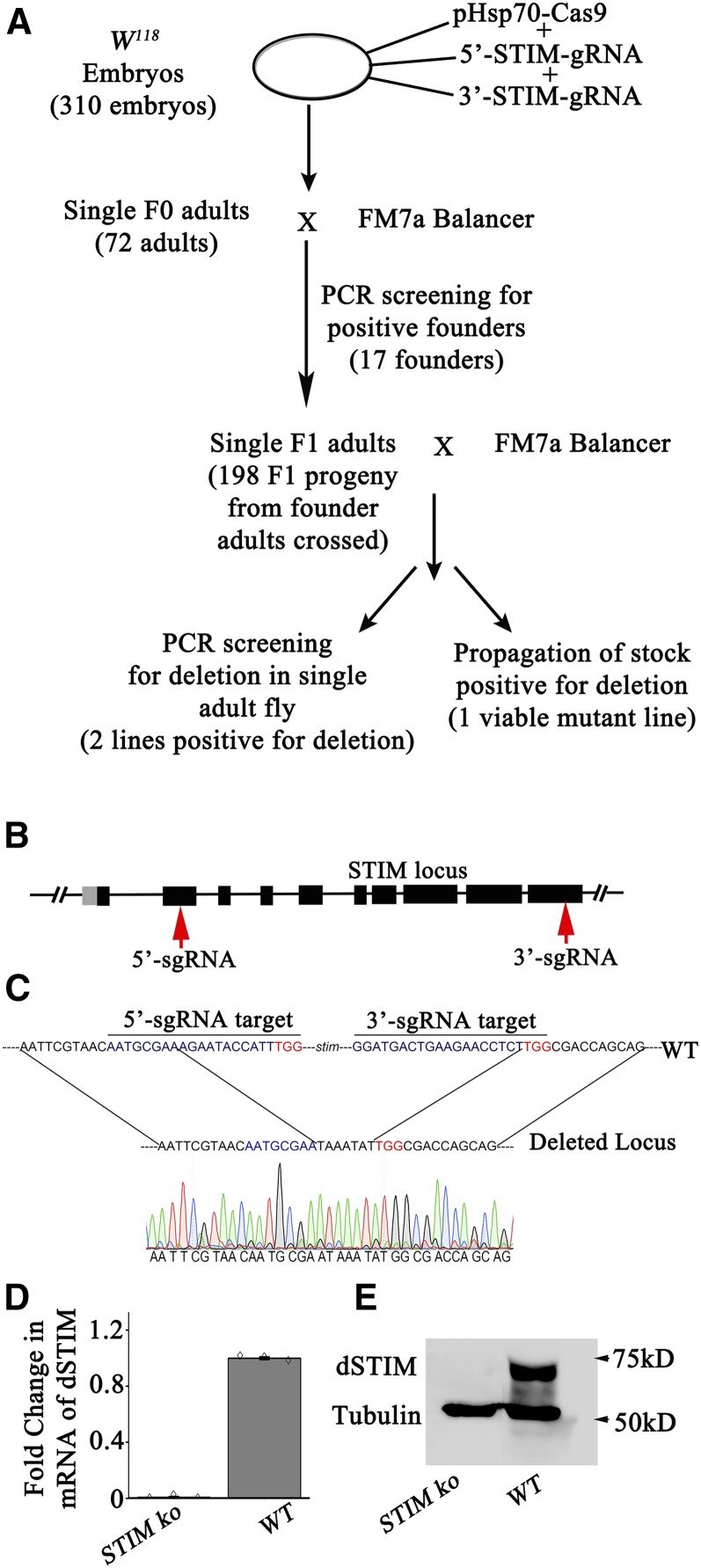

Figure 1.

Knocking out dSTIM with the CRISPR-Cas9 system resulted in deletion of the dSTIM gene (A) Schematic representation for generation of STIM knockout (STIMko). Putative alleles were screened by PCR and balanced using first chromosome balancer FM7a. (B) Representation of dSTIM gene with exons (thick lines), introns (thin lines), and 5′−UTR (gray line). Target regions of guide RNAs are indicated with red arrows. (C) Sequencing of the dSTIM gene region confirming the deletion. (D) q-PCR of RNA isolated from STIMko second instar larvae (n = 3). The error bars represent SEMs. (E) Western blot of protein lysates from second instar larva of STIMko organisms. CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; q-PCR, quantitative PCR; UTR, untranslated region; WT, wild-type.

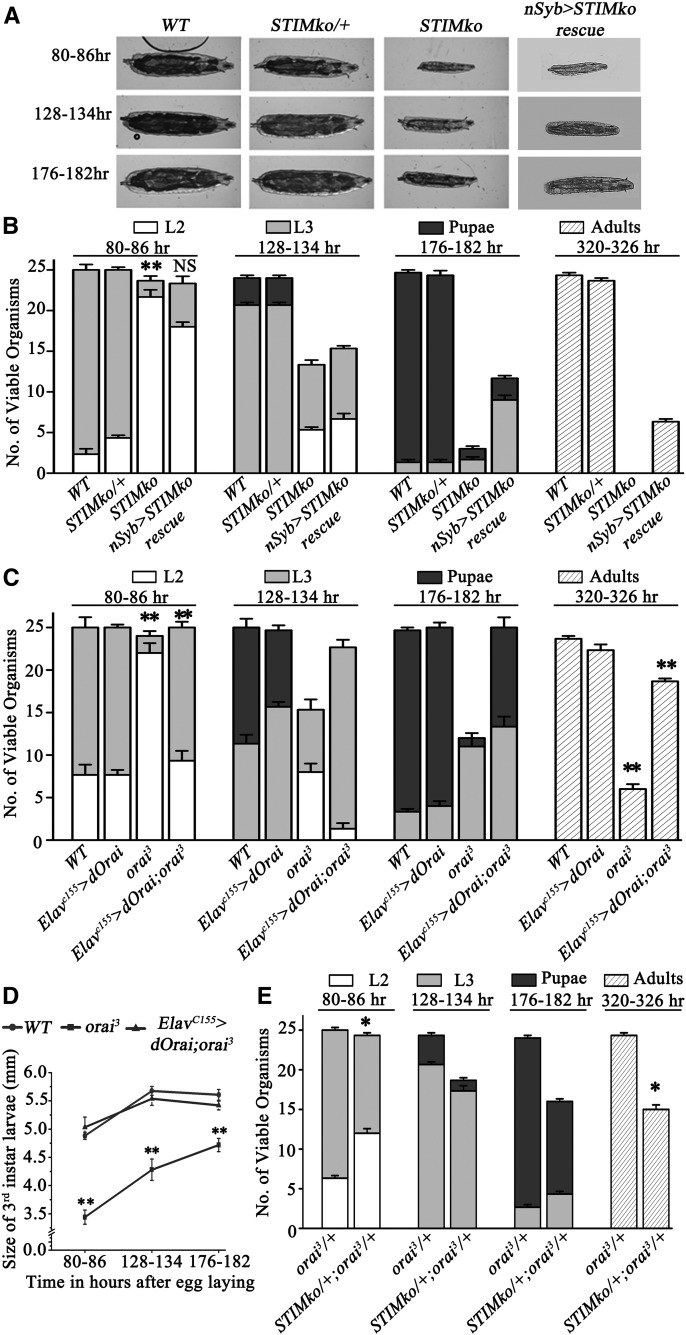

Figure 2.

dSTIM knockout organisms are third instar larval lethal. (A) Larval images represent size and stage at indicated times in hours AEL. (B) The bar graph represents average number of viable organisms at the indicated time in hours AEL (± SEM). Each bar represents number of viable organisms (out of 25 organisms) and their stage of life cycle. L2 stands for second and L3 for third instar larval stage, respectively. STIM knockout (STIMko) organisms die as late second or early third instar larvae and exhibit slow growth, which was partially rescued by pan-neuronal overexpression of dSTIM (nSyb > STIMko rescue), **P < 0.001. (C) orai3 homozygotes lag behind in development and start dying as third instar larvae. Pan-neuronal over expression of dOrai (ElavC155 > dOrai;orai3) rescued both larval lethality and slow growth of orai3 homozygotes. (D) Line graph represents third instar larval size at particular time points. Larvae of orai3 homozygotes were smaller compared to controls. The reduced size of orai3 homozygotes was rescued by pan-neuronal dOrai expression (n = 3*10, Student’s t-test **P < 0.001). (E) Heteroallelic combination of STIMko and orai3 (STIMko/+;orai3/+) showed partial lethality, *P < 0.05. Numbers of second instar larvae at 80–86 hr and adults at 320–326 hr were compared by the Student’s t-test. The genotypes compared, with their P-values, are given in Table 3. AEL, after egg laying; NS, not significant; WT, wild-type.

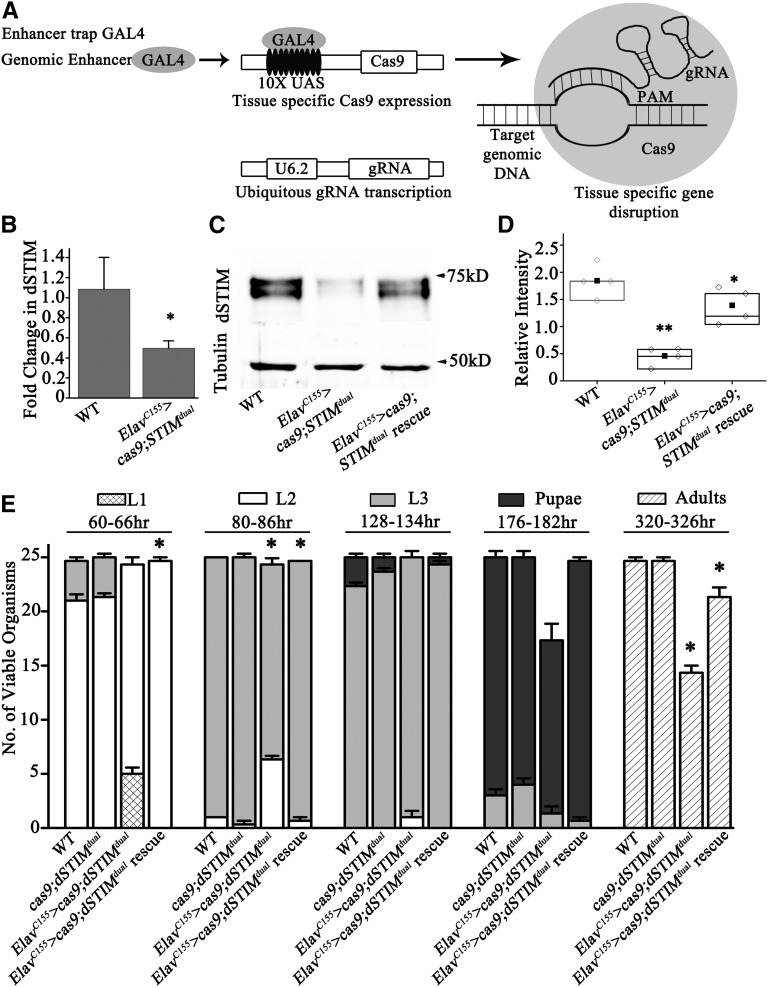

Figure 3.

Pan-neuronal knock out of dSTIM leads to lethality of third instar larvae. (A) Schematic representation of the method for knocking out dSTIM from specific cells and/or tissues. Cas9 is under the UAS promoter expression, which is controlled by GAL4. Expression of the gRNA pair is driven across all tissues by the U6.2 promoter. (B) q-PCR with RNA isolated from the CNS of third instar larvae of the indicated genotypes. ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual (n = 3, *P < 0.05) show reduced dSTIM transcript levels as compared to WT controls. (C) A representative western blot from the CNS of ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms showing reduced levels of dSTIM protein. The CNS lysate from ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual;dSTIM (rescue) organisms exhibits higher dSTIM protein expression as compared with ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms. (D) Quantification of the relative intensity of dSTIM bands as compared with tubulin (n = 3, Student’s t-test **P < 0.001, *P < 0.05). (E) Staging of animals with pan-neuronal knockout of dSTIM (ElavC155 > STIMdual) and their rescue by overexpressing dSTIM (ElavC155 > cas9; STIMdual; dSTIM). The Cas9 transgene is present in all organisms except WT. Error bars represent SEMs. Numbers of second instar larvae at 80–86 hr and adults at 320–326 hr were compared by the Student’s t-test. The genotypes compared, with their P-values, are given in Table 3. CNS, central nervous system; gRNA, guide RNA; q-PCR, quantitative PCR; WT, wild-type.

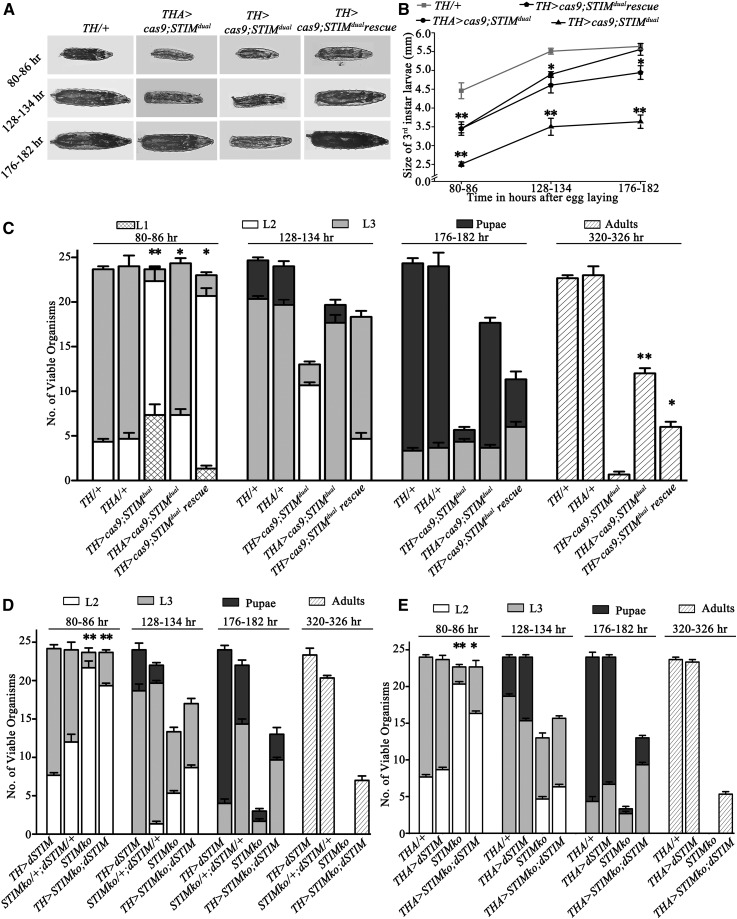

Figure 4.

Knock out of the dSTIM gene from dopaminergic cells resulted in larval lethality. (A) Larval images at the indicated time in hours AEL. TH > cas9;STIMdual organisms were smaller as compared to control THGAL4 heterozygotes (TH/+). (B) The line graph represents size of third instar larvae at indicated time points. TH > cas9;STIMdual were smaller as compared to THGAL4 heterozygotes (TH/+). Overexpression of dSTIM (TH > cas9;STIMdual rescue) partially rescued the larval size compared to TH > cas9;STIMdual organisms. dSTIM knockout from the hypoderm (THA > cas9;STIMdual) also resulted in reduced larval size at 80–86 hr and 128–134 hr AEL compared to TH/+ organisms (N = 10, Student’s t-test *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001). (C) TH > cas9;STIMdual and THA > cas9;STIMdual organisms were lethal at larval stage. They were partially rescued by dSTIM overexpression in dopaminergic cells. (D) Overexpression of dSTIM (UASdSTIM) in dopaminergic neurons (TH > STIMko;dSTIM) partially rescued the larval lethality of STIMko organisms. The STIMko data are as in Figure 2B and are included here for ease of comparison. Both experiments were performed simultaneously. (E) Overexpression of dSTIM in TH-producing cells of the cuticle (THA > STIMko;dSTIM) partially rescued the larval lethality of STIMko organisms. The number of adults of TH > STIMko;dSTIM and THA > STIMko;dSTIM was not compared to STIMko because STIMko organisms were lethal. Numbers of second instar larvae at 80–86 hr and adults at 320–326 hr were compared by the Student’s t-test. The genotypes compared, with their P-values, are given in Table 3. AEL, after egg laying; TH, tyrosine hydrolase.

Results

Generation of a KO for dSTIM using the CRISPR-Cas9 system

A null allele for dSTIM was generated with the CRISPR-Cas9 methodology (Jinek et al. 2012; Cong et al. 2013; Gratz et al. 2013; Mali et al. 2013; Ren et al. 2013). For this purpose, two sgRNAs that were individually designed to target double-stranded breaks at the 5′- and 3′- ends of the dSTIM gene were introduced in Drosophila embryos with a plasmid encoding Cas9 (see Materials and Methods for details). Animals with a deficiency of the complete coding region of the dSTIM gene (Figure 1B) were identified by a PCR strategy after obtaining DNA from heterozygotes at the F1 generation (Figure 1A and Figure S1A). Approximately 198 FM7a balanced heterozygous flies were screened by PCR, from which we obtained two flies with a putative deletion for dSTIM (Figure 1A and Figure S1B). The dSTIM deletion was confirmed by sequencing of genomic DNA obtained from larvae of dSTIM KO homozygotes (STIMko, Figure 1C). To further confirm the dSTIM deletion, q-PCRs and westerns were performed from RNA and protein isolated from the second instar larvae of STIMko organisms. dSTIM transcripts were undetectable in STIMko organisms as compared to controls (Figure 1D). Concurrent with this, dSTIM protein was undetectable in STIMko organisms (Figure 1E).

Whole-body KO of dSTIM and orai3 homozygotes are larval lethal

To begin understanding the functional significance of reduced SOCE during Drosophila development, the viability of homozygous STIMko organisms was determined. Complete STIMko organisms were consistently smaller (Figure 2A) and did not survive beyond late second or early third instar larval stages (Figure 2B). STIMko homozygotes began to exhibit a delay in development from 80 to 86 hr AEL. Among the batches of 25 larvae counted from STIMko organisms, 21.6 ± 0.8 sec instar and 2 ± 0.5 third instar were observed at 80–86 hr, indicating a significant delay in larval development when compared to STIMko heterozygotes (STIMko/+) of which just 4.3 ± 0.3 remained as second instar, whereas 20.6 ± 0.3 had progressed to the third instar larval stage. From 128 to 134 hr onwards, STIMko organisms exhibited lethality. Viable STIMko organisms were present as either second instar (5.3 ± 0.3) or third instar larvae (8 ± 0.5; Figure 2B). In contrast, control STIMko/+ organisms, had progressed to either late third instar larvae (20.6 ± 0.3) or pupae (2.6 ± 0.3; Figure 2B). At 176–182 hr, the majority of STIMko organisms were dead whereas controls were mostly pupae (23.3 ± 0.5) and very few were third instar larvae (1.3 ± 0.3) (Figure 2B). Because CRISPR-Cas9 can introduce mutations at nontarget sites, the ability of a dSTIM transgene (UASdSTIM; Agrawal et al. 2010; Port et al. 2014) to rescue lethality in STIMko organisms was tested by expression with a ubiquitously expressed GAL4 (Actin5cGAL4). More than 80% STIMko animals were rescued (20.3 ± 0.3) and emerged as adults by ubiquitous expression of dSTIM, indicating that lethality in the CRISPR-Cas9-generated KO strain was primarily due to loss of the dSTIM gene (Figure S2F).

The best understood cellular role for STIM is in activation of the store-operated Ca2+ channel, Orai, after depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores (Feske et al. 2006; Prakriya et al. 2006; Vig et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2006). However, instances where STIM can interact with and activate Ca2+ channels other than Orai are also known (Soboloff et al. 2006; Brandman et al. 2007; Park et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2010; Nguyen et al. 2013). To understand if lethality in STIMko organisms is a consequence of reduced SOCE through dOrai, viability of orai3 larvae was measured. orai3 is a previously described hypomorphic allele of dOrai (Cuttell et al. 2008; Pathak et al. 2015). Concurrent with lethality of STIMko larvae, orai3 homozygotes were 80% lethal as third instar larvae (Figure 2C). Moreover, orai3 homozygous larvae were smaller in size as compared to control (WT) organisms (Figure 2D and Figure S2A). However, unlike STIMko organisms, a greater number of orai3 larvae could pupate (∼25%). orai3 pupae were viable and eclosed as adults (Figure 2C). Both orai3 homozygous larvae and adults appeared smaller in size as compared to CS controls (Figure 2D and Figure S2, A and C). If lethality of both STIMko and orai3 larvae is indeed a consequence of reduced SOCE through Orai, we predicted that single copies of STIMko and orai3 in the same organism should exhibit lethality. Indeed, STIMko/+; orai3/+ females are partially inviable (15.0 ± 0.6; Figure 2E), as compared to individual heterozygotes where no significant lethality was observed (Figure 2, B and E).

Next, to test the tissue-specific requirement for SOCE in Drosophila larvae, rescue of STIMko and orai3 organisms was tested by overexpression of cDNAs encoding either dSTIM or dOrai. Pan-neuronal overexpression of dSTIM with nSybGAL4 did not rescue larval size (Figure 2A) and slower development (Figure 2B), but it did rescue lethality of STIMko organisms to an extent (6.3 ± 0.3 adults; Figure 2B). Residual lethality of nSyb > STIMko;UASSTIM organisms was at late second and third instar larval stages (Figure 2B). All nSyb > STIMko;UASSTIM pupae eclosed as adults, supporting a requirement for SOCE in the development of the nervous system in pupae (Pathak et al. 2015).

A requirement for SOCE in postembryonic development of the nervous system was reiterated upon pan-neuronal expression of dOrai with ElavC155GAL4 in orai3 homozygotes (Figure 2C). Whereas just 6 ± 0.5 homozygous orai3 organisms survive to adulthood, ∼80% of rescued larvae eclosed as adults (18.6 ± 0.3) after normal progression through larval stages. Rescued orai3 homozygous larvae appeared normal in size (5.4 ± 0.07 mm at 176–182 hr) and as adults (2.68 ± 0.03 mm) (Figure 2D and Figure S2, A and C). Control animals including orai3 heterozygotes and animals with pan-neuronal overexpression of dOrai (ElavC155 > dOrai) were viable and developed normally (Figure S2B). These results confirmed that lethality, slow development, and smaller body size of hypomorphic orai3 homozygotes arises primarily from reduced SOCE through dOrai in neurons. The function of dSTIM in neurons and other tissues appeared more complex and was investigated further.

The difference in the extent of rescue by the transgenes encoding WT dSTIM and dOrai (compare Figure 2, B and C) could arise due to differences in GAL4-driven expression from the ElavC155 and nSyb promoters (Figure S2E). In addition, the differential rescue may be attributed to the fact that residual expression of dOrai is seen in orai3 homozygous larvae (a hypomorph; Figure S2D), whereas dSTIM protein is not detectable in dSTIMko larvae (Figure 1E).

Characterization of tissue-specific STIMko

To understand dSTIM function in specific tissues, a modified CRISPR-Cas9 system was developed. For this purpose, a transgenic strain was generated where both 5′- and 3′-guide RNAs for dSTIM (STIMdual) express under control of the ubiquitous U6.2 promoter (Kondo and Ueda 2013; Xue et al. 2014) (Figure 3A). Next, we placed the STIMdual strain with a UAS-Cas9 transgene (Port et al. 2014). The resultant flies were mated with specific GAL4 strains to generate cell and tissue-specific KOs of dSTIM (Figure 3A). To test this system, ElavC155GAL4-driven pan-neuronal expression of Cas9 with STIMdual was attempted. The level of dSTIM transcripts were reduced significantly in the CNS of ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms (Figure 3B), and dSTIM protein was also reduced to slightly less than half of WY levels (Figure 3, C and D). These results confirmed that the cell-specific KO of dSTIM with CRISPR-Cas9 reduced dSTIM transcript and protein levels significantly. Residual dSTIM transcripts and protein could be due to a number of reasons. First, some may derive from nonneuronal and neuronal cells in the brain that express dSTIM but do not express ElavC155GAL4. Second, the method of tissue-specific KO employed here may not drive complete excision of both dSTIM alleles in all GAL4-expressing cells, as evident from recently published studies (see Discussion and Port et al. 2014; Moreno-Mateos et al. 2015).

To further investigate whether the reduced viability of the dSTIM KO strain is due to its function in neurons, the development and viability of ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms was investigated. Pan-neuronal KO of dSTIM led to partial lethality of third instar larvae as compared to control cas9;STIMdual or WT organisms. Similar to STIMko organisms, ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms also develop slowly. At 60–66 hr after AEL, 5.5 ± 0.5 organisms were first instar larvae and 19.6 ± 0.6 were second instar, as compared to controls where all organisms were second instar or third instar. At 80–86 hr, the number of second and third instar larvae in ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms were 6.3 ± 0.3 and 18.5 ± 0.3, respectively, indicating that although second and third instar larvae were not lethal yet, their development was slower as compared to control organisms (Figure 3E). Similarly, at 128–134 hr, ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms persisted as second instar (1 ± 0.5) and third instar (24 ± 0.5) larvae, whereas control cas9;STIMdual organisms were either third instar (23 ± 0.3) or pupae (1.3 ± 0.3; Figure 3E). At 176–184 hr, fewer ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms were observed and these were in third instar (1.3 ± 0.6) and pupal (16 ± 0.5) stages. Control cas9;STIMdual organisms were also present as third instar larvae (4 ± 0.5) and pupae (21 ± 0.5) at this time (Figure 3E). These data demonstrate that ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms were partially lethal as third instar larvae.

ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms that pupated also eclosed as adults (14.3 ± 0.6; Figure 3E). However, all eclosed organisms were females, indicating that ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms were male lethal. The difference in lethality between males and females needs further investigation. Interestingly, overexpression of dSTIM in ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms rescued their developmental delay, but lethality was rescued only partially (21.3 ± 0.8 eclosed adults; Figure 3E). The difference between rescue of developmental delay and lethality may be due to incomplete rescue of dSTIM expression in the CNS of ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual; dSTIM organisms (Figure 3, C and D). It is possible that the threshold for rescue of developmental delay by dSTIM is lower, whereas it is higher for rescue of lethality.

Similarly, KO of dSTIM with another pan-neuronal driver (nSybGAL4) resulted in larval lethality. nSyb > cas9;STIMdual organisms were also lethal as third instar larvae. Both males and females were present among the adults that eclosed (15.3 ± 1.2; Figure S3). Pan-neuronal overexpression of dSTIM or cas9 alone did not result in lethality (Figure S3). In contrast to STIMko organisms, the larval size of ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms was similar to controls. Thus, dSTIM function is required in neurons of late second and third instar larvae for viability of Drosophila. The absence of growth deficits in ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms could be due to partial KO (Figure 3, B–D). Alternatively, the growth deficits in STIMko might be due to a requirement for dSTIM in nonneuronal tissues where ElavC155 GAL4 does not express.

SOCE is required in dopaminergic cells for viability of Drosophila

Next, we investigated the classes of neurons that require dSTIM/dOrai function for larval viability. Overexpression of dOrai in either dopaminergic (THGAL4) or glutamatergic (OK371GAL4) neurons of orai3 homozygotes resulted in partial rescue of lethality and delay in larval development (Figure S4, A and B). Rescue of lethality from dopaminergic neurons was better (13 ± 0.6 adults) as compared with glutamatergic neurons (9 ± 0.6 adults). Lethality of orai3 homozygous larvae was not rescued by overexpression of dOrai in either peptidergic neurons (c929GAL4) or muscles (Dmef2GAL4) (Figure S4, C and D). These data suggest that SOCE through the STIM/Orai pathway is required in dopaminergic cells for larval viability. This idea was tested further by investigating lethality and developmental profiles of TH > cas9;STIMdual organisms with KO of dSTIM in dopaminergic cells. TH > cas9;STIMdual organisms were developmentally delayed as evident from the presence of first instar larvae (7.3 ± 1.2) at 80–86 hr AEL and the persistence of second instar larvae (10.6 ± 0.3) at 128–134 hr AEL (Figure 4C). In addition, TH > cas9;STIMdual organisms are almost completely inviable. The average number of adults that eclosed from TH > cas9;STIMdual organisms was 0.6 ± 0.3 (Figure 4C). Overexpression of WT dSTIM in a background of TH > cas9;STIMdual organisms partially rescued lethality (6 ± 0.5 adults) and developmental delay (Figure 4, A–C). To understand why greater lethality was observed in TH > cas9;STIMdual organisms as compared with ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms, we analyzed the extent of overlap between TH- and Elav-expressing neurons in post 80–86-hr-old larval brains. Indeed, at this stage of brain development the overlap of TH-positive cells and ElavC155 > GFP -positive cells was incomplete, both in the brain lobes (Figure S5D) and the ventral ganglion (data not shown). For example, ElavC155 > GFP expression was present in the DM cluster of TH-positive cells, but the DL1 and DL2 clusters (Friggi-Grelin et al. 2003) were not marked by ElavC155 > GFP (Figure S5D). These data do not rule out the possibility of ElavC155-driven expression of UAScas9 in all TH-expressing cells at earlier stages of larval development, possibly resulting in early targeting of the dSTIM locus by the STIMdual transgene. However, they do establish the lack of a complete overlap between expression of ElavC155GAL4 and THGAL4 through all developmental stages of the larval CNS. Thus, even though ElavC155GAL4 expresses in many more cells and expression of THGAL4 is restricted to fewer cells (compare Figure S2E and Figure S5D), there is apparently a greater requirement for dSTIM in cells expressing TH. However, this requirement does not result in a loss of TH cells. When TH cells were counted in larval brains from TH > mGFP and TH > mGFP; cas9;STIMdual organisms at 80–86 hr AEL and 176–182 hr AEL, the numbers obtained from both genotypes matched published data (Friggi-Grelin et al. 2003; Figure S5C).

It is known that, in addition to expression in neurons, TH (encoded by TH) is expressed in the hypodermal cells and is required for melanization (Marsh and Wright 1980; Wright 1987; Birman et al. 1994). To understand if the loss of viability in TH > cas9;STIMdual organisms arises as a consequence of loss of dSTIM function in the hypoderm, we tested viability of THA > cas9;STIMdual organisms. The THA-GAL4 strain does not express in TH neurons (Liu et al. 2012 and Figure S5A). THA > cas9;STIMdual organisms were partially lethal at late second and early third instar larval stages but did not appear developmentally delayed (Figure 4C). However, THA > cas9;STIMdual organisms were smaller in size compared to THA/+ control organisms (Figure 4, A and B). The extent of larval lethality was significantly less as compared with TH > cas9;STIMdual organisms, and there was no pupal lethality (Figure 4C). These data suggest a significant requirement for dSTIM function and SOCE in larval dopaminergic cells in the brain and in the hypoderm. A possible reason for lethality of TH > cas9;STIMdual larvae could be that dSTIM in hypodermal TH cells is required for the formation of mouth hooks, in turn essential for feeding. However, mouth hooks of TH > cas9;STIMdual and THA > cas9;STIMdual organisms appeared normal (Figure S5B). Next, we tested the extent of rescue of STIMko organisms by overexpression of dSTIM in dopaminergic cells. Indeed, a partial rescue was observed. A few TH > STIMko;dSTIM (7 ± 0.5) and THA > STIMko;dSTIM (5.3 ± 0.3) organisms eclosed as adults as compared to STIMko organisms that were completely lethal (Figure 4, D and E). However, STIMko organisms with overexpression of dSTIM in TH-expressing cells (either with TH or THA-GAL4) continued to exhibit significant larval lethality and developmental delays (Figure 4, D and E). Thus, dSTIM function is required in dopaminergic cells but expression in dopaminergic cells alone is insufficient for complete rescue of viability. These data confirm a role for SOCE in dopaminergic neurons for the development and viability of larvae, and support a novel role for dSTIM in TH-expressing cells of the hypoderm.

Discussion

The two major components of SOCE, STIM and Orai, have been implicated in both vertebrate and invertebrate development. In this study, we generated a complete KO for the dSTIM gene, as well as a modified inducible version, so as to understand the role of dSTIM in the development and viability of Drosophila. To generate STIMko animals, we adopted the CRISPR-Cas9 technique and screened for putative heterozygous STIMko founders by PCR. A comparison of the phenotypes of STIMko organisms with an existing orai hypomorphic allele established that SOCE is required during second and early third instar for viability. Results from a combination of rescue experiments, plus an inducible strain designed for generating dSTIM KOs, demonstrate that a major focus of SOCE requirement are dopaminergic neurons in the CNS (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3). This is significant because dopaminergic neurons are known to regulate multiple aspects of neuronal physiology and behavior in mammals and Drosophila (Schultz 2007; Yamamoto and Seto 2014). In addition, dSTIM function may be required in nonneuronal cells for growth and viability. It remains to be established if all phenotypes associated with the KO of dSTIM arise as a consequence of loss of SOCE through Orai or from the ability of STIM to regulate other channels including the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Harraz and Altier 2014). A role for SOCE in the larval CNS agrees with previous findings of IP3R mutants (Joshi et al. 2004), and more recent studies demonstrating that the IP3R regulates SOCE in Drosophila neurons (Venkiteswaran and Hasan 2009; Chakraborty et al. 2016; Deb et al. 2016). The precise target(s) of SOCE in the larval nervous system and in nonneuronal cells needs further investigation.

Table 1. Comparison of lethality, developmental delay, and body size on knocking out dSTIM or reducing dOrai function.

| Genotype | Percentage Lethality | Developmental Delay | Small Body Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| STIMko | 100 | ++ | ++ |

| orai3 | 80 | ++ | ++ |

| ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual | 45 | + | — |

| nSyb > cas9;STIMdual | 40 | + | — |

| TH > cas9;STIMdual | 98 | ++ | ++ |

| THA > cas9;STIMdual | 50 | + | + |

, strength of phenotype; —, no phenotype; TH, tyrosine hydrolase.

Table 2. Comparison of rescue of lethality, developmental delay, and body size on overexpressing dSTIM or dOrai in background of dSTIM knockout or orai3, respectively.

| Genotype | Percentage Rescue of Lethality | Rescue of Developmental Delay | Rescue of Body Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| nSyb > STIMko;dSTIM | 20 | — | — |

| TH > STIMko;dSTIM | 30 | + | — |

| THA > STIMko;dSTIM | 20 | + | — |

| TH > cas9;STIMdual;dSTIM | 25 | + | ++ |

| ElavC155 > orai3;dOrai | 80 | ++ | ++ |

| nSyb > orai3;dOrai | 45 | ++ | ++ |

| TH > orai3;dOrai | 45 | ++ | ++ |

| OK371 > orai3;dOrai | 10 | + | + |

| c929 > orai3;dOrai | — | — | — |

| dMef2 > orai3;dOrai | — | — | — |

—, no rescue; +, strength of rescue; TH, tyrosine hydrolase.

Interestingly, complete lethality, developmental delays, and growth deficits of STIMko larvae and pupae was replicated closely by specific targeting of the dSTIM locus in dopaminergic cells. Indeed, pan-neuronal targeting of the dSTIM locus resulted in only 40–45% lethality, suggesting that dopaminergic cells are especially susceptible to loss of SOCE. An alternate explanation for differences between the extent of lethality observed in organisms when STIMdual; cas9 is driven by either ElavC155GAL4 or THGAL4 could be a low level of differential leaky GAL4 expression in nonneuronal tissues, and therefore “nonspecific” expression of the UAScas9 construct in the two strains. At present, we are unable to resolve this issue, but based on the stronger phenotype of TH > STIMdual vs. ElavC155 > STIMdual (compare Figure 3E with Figure 4C) this seems unlikely, because visible nonspecific expression of THGAL4 (as viewed by driving UASmGFP in early third instar larvae; Figure S5A) is considerably more restricted in the whole animal as compared to expression of ElavC155GAL4 (data not shown). It should be possible to address this more rigorously in future by generating fluorescently-marked dSTIM alleles, allowing for visualization of loss of one or both alleles in any tissue of interest.

The difference in lethality observed between ElavC155GAL4- and THGAL4-driven STIMdual could in part also arise due to differential efficiency of tissue-specific mutagenesis in the two GAL4 strains. It should be possible to address this issue in future by using a strain that creates dSTIM KOs at a higher efficiency. The STIMdual strain used in this study targets two sites at the ends of the dSTIM open reading frame with the idea that they should create a complete KO (see Materials and Methods). The detectable presence of dSTIM transcripts and protein in larval brain lysates of ElavC155GAL4 > STIMdual;cas9 suggests that a complete KO of both alleles may not occur in all neuronal cells marked by ElavC155GAL4, though some of the residual transcripts and protein could arise from nonneuronal cells, such as glia that do not express ElavC155GAL4. Recent studies suggest that increasing the target sites to three or more within a locus is a more dependable strategy for obtaining tissue-specific KOs (Sunagawa et al. 2016).

Nevertheless, a critical requirement for SOCE in dopaminergic cells is supported by earlier results with cell- and tissue-specific knockdown of SOCE components (Pathak et al. 2015). Whereas the KO data (Table 1) strongly implicate dopaminergic cells as the focus of SOCE requirement in larvae, the rescue experiments (Table 2) also support a pan-neuronal requirement for dSTIM and dOrai. Pan-neuronal (ElavC155GAL4) overexpression of dOrai rescued lethality of orai3 homozygotes to a greater extent than overexpression from dopaminergic cells alone (Figure 2B, Figure S4A, and Table 2), though developmental delays and size were rescued to similar extents. However, in STIMko organisms, both pan-neuronal and dopaminergic overexpression led to a partial and comparable level of rescue of lethality (Figure 2B, Figure 4D, and Table 2). We attribute these differences to the hypomorphic nature of the orai3 allele, as compared to dSTIMko which is a null allele. Differential expression patterns of ElavC155GAL4 and nSybGAL4 (Figure S2E) may also contribute to the difference in rescue of orai3 and STIMko organisms. Rescue of STIMko was attempted with nSybGAL4 because the ElavC155GAL4 transgene and STIMko are both on the X chromosome. Despite the near complete lethality of TH > cas9; STIMdual larvae, TH-driven rescue of STIMko organisms remained at 30% (Table 1 and Table 2). dSTIM expression in dopaminergic cells is, thus, not sufficient for complete viability of STIMko animals, and indicates a requirement in other neuronal subdomains and tissues. Previously, it was demonstrated that SOCE is required for the regulation of TH gene transcription in pupae (Pathak et al. 2015). The larval requirement for SOCE in dopaminergic cells may be similar, though effects of SOCE on cellular processes other than gene regulation remain a possibility.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material is available online at www.g3journal.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/g3.116.038539/-/DC1.

Acknowledgments

Stocks obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (National Institutes of Health P40OD018537) were used in this study. We thank the Fly Facility, Centre for Cellular and Molecular Platforms, National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) for generating transgenic fly lines, and H. Krishnamurthy and the NCBS Central Imaging and Flow Facility for help with confocal imaging. This project was supported by grants from the Department of Science and Technology (http://www.dst.gov.in) and NCBS, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (http://www.ncbs.res.in) to G.H. T.P. is supported by a research fellowship from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (http://www.csir.res.in). The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: B. Oliver

Literature Cited

- Agrawal N., Venkiteswaran G., Sadaf S., Padmanabhan N., Banerjee S., et al. , 2010. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and dSTIM function in Drosophila insulin-producing neurons regulates systemic intracellular calcium homeostasis and flight. J. Neurosci. 30: 1301–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner, M., 1989 Drosophila: A Laboratory Handbook. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Baba Y., Nishida K., Fujii Y., Hirano T., Hikida M., et al. , 2008. Essential function for the calcium sensor STIM1 in mast cell activation and anaphylactic responses. Nat. Immunol. 9: 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyersdorf N., Braun A., Vögtle T., Varga-Szabo D., Galdos R. R., et al. , 2009. STIM1-independent T cell development and effector function in vivo. J. Immunol. 182: 3390–3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birman S., Morgan B., Anzivino M., Hirsh J., 1994. A novel and major isoform of tyrosine hydroxylase in Drosophila is generated by alternative RNA processing. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 26559–26567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof J., Maeda R. K., Hediger M., Karch F., Basler K., 2007. An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific phiC31 integrases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 3312–3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandman O., Liou J., Park W. S., Meyer T., 2007. STIM2 is a feedback regulator that stabilizes basal cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ levels. Cell 131: 1327–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brini M., Cali T., Ottolini D., Carafoli E., 2014. Neuronal calcium signaling: function and dysfunction. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71: 2787–2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X., 2007. Molecular evolution and structural analysis of the Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel subunit, Orai. J. Mol. Biol. 368: 1284–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S., Deb B. K., Chorna T., Konieczny V., Taylor C. W., et al. , 2016. Mutant IP3 receptors attenuate store-operated Ca2+ entry by destabilizing STIM–Orai interactions in Drosophila neurons. J. Cell Sci. 129: 3903–3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham D. E., 2007. Calcium signaling. Cell 131: 1047–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L., Ran F. A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., et al. , 2013. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339: 819–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuttell L., Vaughan A., Silva E., Escaron C. J., Lavine M., et al. , 2008. Undertaker, a Drosophila Junctophilin, links Draper-mediated phagocytosis and calcium homeostasis. Cell 135: 524–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb B. K., Pathak T., Hasan G., 2016. Store-independent modulation of Ca2+ entry through Orai by Septin 7. Nat. Commun. 7: 11751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S., Gwack Y., Prakriya M., Srikanth S., Puppel S.-H., et al. , 2006. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 441: 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friggi-Grelin F., Coulom H., Meller M., Gomez D., Hirsh J., et al. , 2003. Targeted gene expression in Drosophila dopaminergic cells using regulatory sequences from tyrosine hydroxylase. J. Neurobiol. 54: 618–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz S. J., Cummings A. M., Nguyen J. N., Hamm D. C., Donohue L. K., et al. , 2013. Genome engineering of Drosophila with the CRISPR RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease. Genetics 194: 1029–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwack Y., Srikanth S., Oh-Hora M., Hogan P. G., Lamperti E. D., et al. , 2008. Hair loss and defective T- and B-cell function in mice lacking ORAI1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28: 5209–5222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harraz O. F., Altier C., 2014. STIM1-mediated bidirectional regulation of Ca(2+) entry through voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCC) and calcium-release activated channels (CRAC). Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan G., Venkiteswaran G., 2010. The enigma of store-operated ca-entry in neurons: answers from the Drosophila flight circuit. Front. Neural Circuits 4: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewes R. S., Park D., Gauthier S. A., Schaefer A. M., Taghert P. H., 2003. The bHLH protein Dimmed controls neuroendocrine cell differentiation in Drosophila. Development 130: 1771–1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J. A., et al. , 2012. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337: 816–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R., Venkatesh K., Srinivas R., Nair S., Hasan G., 2004. Genetic dissection of itpr gene function reveals a vital requirement in aminergic cells of Drosophila larvae. Genetics 166: 225–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S., Ueda R., 2013. Highly improved gene targeting by germline-specific Cas9 expression in Drosophila. Genetics 195: 715–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J., Fivaz M., Inoue T., Meyer T., 2007. Live-cell imaging reveals sequential oligomerization and local plasma membrane targeting of stromal interaction molecule 1 after Ca2+ store depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 9301–9306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Liu S., Kodama L., Driscoll M. R., Wu M. N., 2012. Two dopaminergic neurons signal to the dorsal fan-shaped body to promote wakefulness in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 22: 2114–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P., Yang L., Esvelt K. M., Aach J., Guell M., et al. , 2013. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 339: 823–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh J. L., Wright T. R., 1980. Developmental relationship between dopa decarboxylase, dopamine acetyltransferase, and ecdysone in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 80: 379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Mateos M. A., Vejnar C. E., Beaudoin J.-D., Fernandez J. P., Mis E. K., et al. , 2015. CRISPRscan: designing highly efficient sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9 targeting in vivo. Nat. Methods 12: 982–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen N., Biet M., Simard É., Béliveau É., Francoeur N., et al. , 2013. STIM1 participates in the contractile rhythmicity of HL-1 cells by moderating T-type Ca2+ channel activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833: 1294–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh-Hora M., Yamashita M., Hogan P. G., Sharma S., Lamperti E., et al. , 2008. Dual functions for the endoplasmic reticulum calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 in T cell activation and tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 9: 432–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C. Y., Shcheglovitov A., Dolmetsch R., 2010. The CRAC channel activator STIM1 binds and inhibits L-type voltage-gated calcium channels. Science 330: 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S., Joseph S. K., Thomas A. P., 1999. Molecular properties of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Cell Calcium 25: 247–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak T., Agrawal T., Richhariya S., Sadaf S., Hasan G., 2015. Store-operated calcium entry through Orai is required for transcriptional maturation of the flight circuit in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 35: 13784–13799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port F., Chen H.-M., Lee T., Bullock S. L., 2014. Optimized CRISPR/Cas tools for efficient germline and somatic genome engineering in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111: E2967–E2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya M., Lewis R. S., 2015. Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol. Rev. 95: 1383–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya M., Feske S., Gwack Y., Srikanth S., Rao A., et al. , 2006. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature 443: 230–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X., Sun J., Housden B. E., Hu Y., Roesel C., et al. , 2013. Optimized gene editing technology for Drosophila melanogaster using germ line-specific Cas9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: 19012–19017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J., DiGregorio P. J., Yeromin A. V., Ohlsen K., Lioudyno M., et al. , 2005. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J. Cell Biol. 169: 435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadaf S., Reddy O. V., Sane S. P., Hasan G., 2015. Neural control of wing coordination in flies. Curr. Biol. 25: 80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal S., Jennings T., Dowse H., Ramaswami M., 2006. Conditional mutations in SERCA, the Sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca 2+-ATPase, alter heart rate and rhythmicity in Drosophila. J. Comp. Physiol. B 176: 253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W., 2007. Multiple dopamine functions at different time courses. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30: 259–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soboloff J., Spassova M. A., Hewavitharana T., He L.-P., Xu W., et al. , 2006. STIM2 is an inhibitor of STIM1-mediated store-operated Ca2+ entry. Curr. Biol. 16: 1465–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiber J., Hawkins A., Zhang Z.-S., Wang S., Burch J., et al. , 2008. STIM1 signalling controls store-operated calcium entry required for development and contractile function in skeletal muscle. Nat. Cell Biol. 10: 688–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunagawa G. A., Sumiyama K., Ukai-Tadenuma M., Perrin D., Fujishima H., et al. , 2016. Mammalian reverse genetics without crossing reveals Nr3a as a short-sleeper gene. Cell Rep. 14: 662–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkiteswaran G., Hasan G., 2009. Intracellular Ca2+ signaling and store-operated Ca2+ entry are required in Drosophila neurons for flight. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009: 10326–10331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig M., Peinelt C., Beck A., Koomoa D. L., Rabah D., et al. , 2006. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science 312: 1220–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Deng X., Mancarella S., Hendron E., Eguchi S., et al. , 2010. The calcium store sensor, STIM1, reciprocally controls Orai and CaV1.2 channels. Science 330: 105–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright T. R., 1987. The genetics of biogenic amine metabolism, sclerotization, and melanization in Drosophila melanogaster. Adv. Genet. 24: 127–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Z., Wu M., Wen K., Ren M., Long L., et al. , 2014. CRISPR/Cas9 mediates efficient conditional mutagenesis in Drosophila. G3 (Bethesda) 4:2167–2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S., Seto E. S., 2014. Dopamine dynamics and signaling in Drosophila: an overview of genes, drugs and behavioral paradigms. Exp. Anim. 63: 107–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. L., Yeromin A. V., Zhang X. H.-F., Yu Y., Safrina O., et al. , 2006. Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca(2+) influx identifies genes that regulate Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 9357–9362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

There are six supplemental files associated with this manuscript. Data in these supplemental files supports the results of the main figures and text. Supplemental material File S1 contains the detailed figure legends for all the Supplemental figures. Figure S1 contains supporting data for Figure 1 with the results of PCR screening for identifying putative STIMko strains. Figure S2 has genetic controls for the data with orai3 mutants and STIMko presented in Figure 2. Figure S3 contains supporting data and genetic controls for Figure 3. Genetic controls and data supporting a role for dOrai in larval dopaminergic neurons is shown in Figure S4, whereas further data supporting a role of dSTIM in larval dopaminergic neurons is presented in Figure S5. Both Figure S4 and Figure S5 support the results presented in Figure 4.

Figure 1.

Knocking out dSTIM with the CRISPR-Cas9 system resulted in deletion of the dSTIM gene (A) Schematic representation for generation of STIM knockout (STIMko). Putative alleles were screened by PCR and balanced using first chromosome balancer FM7a. (B) Representation of dSTIM gene with exons (thick lines), introns (thin lines), and 5′−UTR (gray line). Target regions of guide RNAs are indicated with red arrows. (C) Sequencing of the dSTIM gene region confirming the deletion. (D) q-PCR of RNA isolated from STIMko second instar larvae (n = 3). The error bars represent SEMs. (E) Western blot of protein lysates from second instar larva of STIMko organisms. CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; q-PCR, quantitative PCR; UTR, untranslated region; WT, wild-type.

Figure 2.

dSTIM knockout organisms are third instar larval lethal. (A) Larval images represent size and stage at indicated times in hours AEL. (B) The bar graph represents average number of viable organisms at the indicated time in hours AEL (± SEM). Each bar represents number of viable organisms (out of 25 organisms) and their stage of life cycle. L2 stands for second and L3 for third instar larval stage, respectively. STIM knockout (STIMko) organisms die as late second or early third instar larvae and exhibit slow growth, which was partially rescued by pan-neuronal overexpression of dSTIM (nSyb > STIMko rescue), **P < 0.001. (C) orai3 homozygotes lag behind in development and start dying as third instar larvae. Pan-neuronal over expression of dOrai (ElavC155 > dOrai;orai3) rescued both larval lethality and slow growth of orai3 homozygotes. (D) Line graph represents third instar larval size at particular time points. Larvae of orai3 homozygotes were smaller compared to controls. The reduced size of orai3 homozygotes was rescued by pan-neuronal dOrai expression (n = 3*10, Student’s t-test **P < 0.001). (E) Heteroallelic combination of STIMko and orai3 (STIMko/+;orai3/+) showed partial lethality, *P < 0.05. Numbers of second instar larvae at 80–86 hr and adults at 320–326 hr were compared by the Student’s t-test. The genotypes compared, with their P-values, are given in Table 3. AEL, after egg laying; NS, not significant; WT, wild-type.

Figure 3.

Pan-neuronal knock out of dSTIM leads to lethality of third instar larvae. (A) Schematic representation of the method for knocking out dSTIM from specific cells and/or tissues. Cas9 is under the UAS promoter expression, which is controlled by GAL4. Expression of the gRNA pair is driven across all tissues by the U6.2 promoter. (B) q-PCR with RNA isolated from the CNS of third instar larvae of the indicated genotypes. ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual (n = 3, *P < 0.05) show reduced dSTIM transcript levels as compared to WT controls. (C) A representative western blot from the CNS of ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms showing reduced levels of dSTIM protein. The CNS lysate from ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual;dSTIM (rescue) organisms exhibits higher dSTIM protein expression as compared with ElavC155 > cas9;STIMdual organisms. (D) Quantification of the relative intensity of dSTIM bands as compared with tubulin (n = 3, Student’s t-test **P < 0.001, *P < 0.05). (E) Staging of animals with pan-neuronal knockout of dSTIM (ElavC155 > STIMdual) and their rescue by overexpressing dSTIM (ElavC155 > cas9; STIMdual; dSTIM). The Cas9 transgene is present in all organisms except WT. Error bars represent SEMs. Numbers of second instar larvae at 80–86 hr and adults at 320–326 hr were compared by the Student’s t-test. The genotypes compared, with their P-values, are given in Table 3. CNS, central nervous system; gRNA, guide RNA; q-PCR, quantitative PCR; WT, wild-type.

Figure 4.

Knock out of the dSTIM gene from dopaminergic cells resulted in larval lethality. (A) Larval images at the indicated time in hours AEL. TH > cas9;STIMdual organisms were smaller as compared to control THGAL4 heterozygotes (TH/+). (B) The line graph represents size of third instar larvae at indicated time points. TH > cas9;STIMdual were smaller as compared to THGAL4 heterozygotes (TH/+). Overexpression of dSTIM (TH > cas9;STIMdual rescue) partially rescued the larval size compared to TH > cas9;STIMdual organisms. dSTIM knockout from the hypoderm (THA > cas9;STIMdual) also resulted in reduced larval size at 80–86 hr and 128–134 hr AEL compared to TH/+ organisms (N = 10, Student’s t-test *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001). (C) TH > cas9;STIMdual and THA > cas9;STIMdual organisms were lethal at larval stage. They were partially rescued by dSTIM overexpression in dopaminergic cells. (D) Overexpression of dSTIM (UASdSTIM) in dopaminergic neurons (TH > STIMko;dSTIM) partially rescued the larval lethality of STIMko organisms. The STIMko data are as in Figure 2B and are included here for ease of comparison. Both experiments were performed simultaneously. (E) Overexpression of dSTIM in TH-producing cells of the cuticle (THA > STIMko;dSTIM) partially rescued the larval lethality of STIMko organisms. The number of adults of TH > STIMko;dSTIM and THA > STIMko;dSTIM was not compared to STIMko because STIMko organisms were lethal. Numbers of second instar larvae at 80–86 hr and adults at 320–326 hr were compared by the Student’s t-test. The genotypes compared, with their P-values, are given in Table 3. AEL, after egg laying; TH, tyrosine hydrolase.