Key Points

Protamine, the clinically used heparin antidote, alters clot structure by direct incorporation, explaining its known adverse effects.

UHRA, a heparin antidote, neutralizes heparin anticoagulation without affecting clotting, clot structure, or lung damage in mice.

Abstract

Anticoagulant therapy–associated bleeding and pathological thrombosis pose serious risks to hospitalized patients. Both complications could be mitigated by developing new therapeutics that safely neutralize anticoagulant activity and inhibit activators of the intrinsic blood clotting pathway, such as polyphosphate (polyP) and extracellular nucleic acids. The latter strategy could reduce the use of anticoagulants, potentially decreasing bleeding events. However, previously described cationic inhibitors of polyP and extracellular nucleic acids exhibit both nonspecific binding and adverse effects on blood clotting that limit their use. Indeed, the polycation used to counteract heparin-associated bleeding in surgical settings, protamine, exhibits adverse effects. To address these clinical shortcomings, we developed a synthetic polycation, Universal Heparin Reversal Agent (UHRA), which is nontoxic and can neutralize the anticoagulant activity of heparins and the prothrombotic activity of polyP. Sharply contrasting protamine, we show that UHRA does not interact with fibrinogen, affect fibrin polymerization during clot formation, or abrogate plasma clotting. Using scanning electron microscopy, confocal microscopy, and clot lysis assays, we confirm that UHRA does not incorporate into clots, and that clots are stable with normal fibrin morphology. Conversely, protamine binds to the fibrin clot, which could explain how protamine instigates clot lysis and increases bleeding after surgery. Finally, studies in mice reveal that UHRA reverses heparin anticoagulant activity without the lung injury seen with protamine. The data presented here illustrate that UHRA could be safely used as an antidote during adverse therapeutic modulation of hemostasis.

Introduction

Heparins are highly sulfated anionic polymers that are commonly used as prophylactic anticoagulants and to treat acute thromboembolism.1 However, the risk for bleeding associated with heparin therapy remains a serious concern,2 and no approved antidotes are available for low–molecular-weight (MW) natural or synthetic (fondaparinux) formulations of heparin.2 Hence, effective strategies to manage bleeding associated with heparin therapy remain a clinical need.

In the last decade, investigations have revealed that other polyanionic biomolecules can participate directly or indirectly in the development of thrombosis. In particular, extracellular nucleic acids,3 polyphosphate (polyP),4 and neutrophil extracellular trap-associated5 DNA are potent activators of blood clotting. Neutralizing these prothrombotic polyanions could therefore be used to treat thrombosis.6

Polycations are used widely to counteract polyanions. For example, protamine sulfate is the only clinically approved antidote for unfractionated heparin (UFH).2 Adverse outcomes to protamine therapy are well-documented and include intrinsic anticoagulant effects, precipitation, nonenzymatic polymerization of fibrinogen, and complement activation.7-10 Likewise, cationic polyethyleneimine and polyamidoamine dendrimers have been tested as polyP and extracellular nucleic acid inhibitors.6,11 Both molecules exhibit cellular toxicity and are not hemocompatible.12,13 The development of new hemocompatible polycations that effectively regulate pro- or anticoagulant effects of polyanions would therefore be of significant clinical value.

We have therefore developed a new class of molecules collectively named Universal Heparin Reversal Agents (UHRAs).14 UHRAs have a unique design composed of a dendritic core decorated with multivalent cationic binding groups (CBGs) shielded within a neutral brush layer of methoxy polyethylene glycol (mPEG) emanating from the core. The general nature of the synthesis platform allows facile creation of libraries of UHRA molecules that differ in their MW and number of CBGs on the scaffold. Through extensive calorimetric screening of binding affinities and stoichiometries among library members, we identified UHRA molecules that bind and inhibit heparins and polyP, respectively, in animal models of bleeding and thrombosis.14,15

Here, we extend our earlier discovery by reporting the effect on plasma coagulation, clot stability, morphology, and organ toxicity of a specific UHRA molecule having high binding affinity to heparin and polyP. Previously tested polycations against heparin and polyP exhibit nonspecific binding to blood proteins and are known to cause alterations in clot morphology and augmented clot dissolution.16,17 Our ex vivo and in vivo studies reported here therefore address the following questions: What is the influence of UHRA on fibrinogen, fibrin polymerization, and thrombin generation? Are fibrin or blood clots that have been formed in the presence of UHRA stable, and do they exhibit normal clot morphology? Does UHRA bind to and/or incorporate into clots? And finally, does UHRA reverse the anticoagulation activity of UFH without lung injury?

The results demonstrate that, in contrast to protamine, UHRA has negligible influence on fibrinogen, blood clotting, and clot morphology. This is supported by our finding that UHRA, unlike protamine, is excluded from fibrin clots and does not bind to blood clot components. Also, UHRA is capable of completely reversing the anticoagulant activity of UFH in mice without causing lung injury. Our results therefore indicate that UHRA is a suitable candidate for further clinical development as an inhibitor of polyanionic pro- and anticoagulant molecules.

Methods

Synthesis of the UHRA molecule used for this study and information regarding reagents, proteins, and blood collection are described in the supplemental Data (Synthesis of UHRA, page 3), available on the Blood Web site.

Ethics statement

The protocol for blood collection was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board (certificate number H10-01896) of the University of British Columbia, and written consent was obtained from donors, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Interaction of UHRA with fibrinogen

The interaction of UHRA with human fibrinogen was studied by spectrofluorometry, circular dichroism (CD), isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) analyses, and fibrin polymerization assay. The procedure used for each method is described in the supplemental Data (page 5).

Plasma clot formation and lysis by turbidity analysis

Microplate-based turbidimetric clotting assays were performed in human platelet-poor plasma to evaluate the effect of UHRA or protamine on clotting and clot lysis. The detailed procedure used is described in the supplemental Data (page 8).

Scanning electron microscopy and confocal microscopy of fibrin and whole blood clots

The morphology of clots formed in the presence of UHRA or protamine was analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM).18 For confocal microscopy, Alexa Fluor 488 was conjugated to UHRA and protamine. The procedures used for fluorophore labeling, confocal microscopy, and SEM imaging are described in the supplemental Data (pages 9-11).

Neutralization of heparin anticoagulation in mice and lung histopathology analyses

All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the University of British Columbia, Canada. The detailed procedure is described in the supplemental Data (pages 13-15).

Data analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE) values from at least 3 independent experiments unless otherwise specified. All results were plotted and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was determined using Student t test or by 1-way ANOVA followed by a Dunnett post hoc test. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Design and synthesis of a UHRA molecule that binds pro- and anticoagulant polyanions

Our previous findings showed that the characteristics of a given UHRA molecule, including MW, number of CBGs, and density of the mPEG brush layer, determine its specificity and efficacy against a particular polyanionic target, as well as its toxicity.14,15 This is expected, as affinity and specificity are dictated in part by a network of coulombic interactions between anions on the target and cationic ligands appropriately spaced on the UHRA to form cognate ion pairs. The mean distance of separation between ligands on a UHRA molecule is therefore a determinant of binding affinity and specificity, and the number of CBGs per MW ratio (#CBGs/MW) provides a metric of that spacing. When UFH is the target polyanion, we showed previously that tight and specific binding can be achieved, with excellent biocompatibility maintained, with a UHRA molecule (UHRA-7) having a #CBGs/MW ratio of circa 1.1.14 Through those investigations, we further showed that binding properties change with MW at a fixed #CBGs/MW because, although their spacing remains similar, the ligands on average reside closer to the surface of the UHRA as MW is decreased. The entropic shielding provided by the brush is therefore reduced. To exploit these properties for drug selection, a library of UHRA molecules of different MW, #CBGs/MW, and brush densities was created and screened to identify a UHRA molecule that exhibits good binding affinity to both heparin and polyP. The synthesis of a UHRA molecule evaluated in the current study is similar to that for UHRA-7 described previously,14 and details are provided in the supplemental Data (supplemental Table S1; supplemental Figures S1 and S2).

ITC data (supplemental Figure S3A-B) demonstrate stoichiometric, well-defined complexes formed between UHRA and either UFH or polyP. In either system, the equilibrium binding constant (Ka) approaches ≈ 106 M−1 (supplemental Table S2).

UHRA does not interact with fibrinogen or alter thrombin-mediated fibrin polymerization

The clotting cascade culminates with thrombin-catalyzed polymerization of fibrinogen into fibrin.19 Fibrinogen is an anionic plasma protein circulating at a concentration of 6 to 12 µM.19 Polycations such as protamine bind fibrinogen largely through intermolecular coulombic attraction, which results in protein aggregation causing coagulopathy and pulmonary hypertension.7,8,13 We studied the interaction of UHRA with fibrinogen by measuring changes in its intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence.16 Binding of polycations quenches fibrinogen fluorescence, as shown with polyethyleneimine (Figure 1A), where a concentration-dependent quenching was observed. From such data, the association constant Ka (M−1) and number of binding sites per fibrinogen molecule, n, may be determined by regression of the relation20:

|

where F and Fo represent fluorescence intensities of fibrinogen in the presence and absence of the polycation, respectively, and [U] is the equilibrium concentration (M) of unbound polycation. Linear least-squares regression of the double logarithm plotted data (R2 = 0.99) provides estimates of Ka and n, which for polyethyleneimine–fibrinogen binding are 4.7 × 106 M−1 and 0.75, respectively.

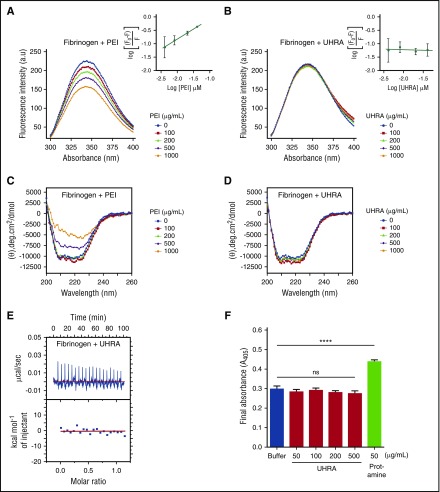

Figure 1.

UHRA does not bind to human fibrinogen or influence fibrin polymerization. For fluorometric experiments, (A) a fixed concentration of fibrinogen (0.25 µM) in 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline containing 137 mM NaCl (pH 7.4) was incubated with either UHRA or polyethyleneimine (PEI) at 37°C for 5 minutes. The solution was then excited at 280 nm, and emission spectra from 300 to 400 nm were recorded to follow the effect of increasing PEI concentrations on the tryptophan fluorescence emission of fibrinogen. PEI quenched the fluorescence signal in a concentration-dependent fashion. (B) The effect of increasing UHRA concentration on the tryptophan fluorescence emission of fibrinogen. The intensity of the fluorescence signal remained unchanged even in the presence of 1000 µg/mL UHRA, indicating minimal interaction of UHRA with fibrinogen. The depicted fluorescence spectra are the average of 3 independent experiments. Error values are small and not shown for data presentation clarity. The insets show the quenching effect of UHRA or PEI on the fibrinogen fluorescence. Data in the inset are mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Experimental settings were as in A. (C) CD experiments were conducted by incubating UHRA or PEI with fibrinogen (0.4 µM) in 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 5 minutes; the equilibrated sample was then scanned from 190 to 260 nm. PEI at 500 or 1000 µg/mL caused significant changes in the secondary structure of fibrinogen. CD spectra shown are baseline-corrected using mean protein-free control scans (n = 2). (D) CD spectra of the fibrinogen–UHRA mixture were acquired as in C. No significant change in ellipticity at 208 and 222 nm was observed. (E) A binding isotherm was obtained using ITC by titrating UHRA with fibrinogen. The upper panel depicts the raw data (power signal), and the lower panel shows the integrated areas corresponding to each injection, normalized to the moles of UHRA injected into fibrinogen solution and plotted as a function of molar ratio (UHRA/fibrinogen). The raw heat data of UHRA titration into fibrinogen solution showed very weak endothermic peaks. This confirmed that UHRA did not bind to fibrinogen. (F) The final turbidity of mature fibrin clots produced from purified fibrinogen in the presence of UHRA or protamine was measured. Even at 500 µg/mL, UHRA did not alter the final turbidity relative to the polycation-free control. In comparison, significant increases in final turbidity are observed as protamine concentration is increased to 50 µg/mL (****P < .0005). All experiments were performed in triplicate. Results are expressed as the mean ± SE of 9 measurements from 3 independent experiments. Unpaired 2-tailed t tests were performed to determine significance, with P < .05 indicating a statistically significant change. Details of ITC and fibrin polymerization experiments are described in the supplemental Data (pages 6-7).

In contrast, the fluorescence profile of fibrinogen was unaffected by the addition of increasing amounts of UHRA (Figure 1B), indicating that UHRA has minimal interaction, if any. To support this observation, we analyzed the secondary structure of fibrinogen in the presence of UHRA or polyethyleneimine, using CD spectroscopy. The α-helical content of pure fibrinogen gives 2 pronounced negative ellipticity peaks at 208 and 222 nm.16 Coincubation of UHRA with fibrinogen does not alter ellipticity at 208 and 220 nm. The presence of polyethyleneimine (500 µg/mL), however, increases ellipticity (Figure 1C-D). Deconvolution of the spectra shows that the native fibrinogen used in this study is composed of circa 30% (±2%) α-helix, 19% (±1%) β-sheet, and 35% (±1%) random coil secondary structure content. In the presence of 1000 µg/mL UHRA, fibrinogen secondary structure is unchanged (30% [±3%] α-helix, 19% [±2%] β-sheet, and 34% [±2%] random coil), again suggestive of at most a weak intermolecular interaction. In contrast, addition of polyethyleneimine alters fibrinogen secondary structure (24% [±1%] α-helix, 23% [±1%] β-sheet, and 40% [±1%] random coil; supplemental Figure S4).

The interaction between UHRA and fibrinogen was also examined directly using ITC, with representative raw and integrated heat data shown in Figure 1E. Titration of UHRA into fibrinogen yields weak endothermic peaks indicating no significant interaction between the 2 components.

Finally, we investigated fibrinogen polymerization by thrombin in the presence of UHRA or protamine. Results demonstrated that UHRA does not significantly change turbidity profiles or final fibrin turbidities relative to the polycation-free control (Figure 1F; supplemental Figure S5). However, protamine addition increased the turbidity significantly in a manner consistent with its interaction with fibrinogen. The final turbidity of fibrin clots correlates with fiber size, with an increase in the final turbidity indicative of thicker fibers, and thus, altered clot structure.19,21 The data therefore demonstrate that, unlike protamine or polyethyleneimine, UHRA does not alter fibrin structures or cause fibrinogen aggregation and/or precipitation (supplemental Figure S6).

UHRA has no effect on tissue factor/recalcification-initiated plasma coagulation and clot lysis

Polycations can perturb the blood-clotting cascade either by initiating or delaying clotting. Polyamidoamine dendrimers, for example, are procoagulant,13 whereas protamine possesses intrinsic anticoagulant properties.9 To investigate the effect of UHRA on clotting, we performed turbidimetric plasma clotting assays. When coagulation was triggered by adding tissue factor (TF) to recalcified plasma containing UHRA, no significant differences in lag time or maximum absorbance were observed, even at 1000 μg/mL UHRA (P = .14 and .10, respectively) compared with the buffer control (Figure 2A-C). The clotting profile of recalcified plasma containing UHRA is likewise comparable to the buffer control (Figure 2D-F). No significant alteration in lag time or maximum absorbance was observed even at 1000 μg/mL UHRA (P = .08 and .29, respectively). In contrast, protamine, even at 50 µg/mL, increased both the lag time and maximum absorbance (P < .001 and < .005, respectively) of TF-induced coagulation of recalcified plasma. It also increased the final turbidity, while demonstrating anticoagulant activity and abnormal fiber formation in the coagulation of recalcified plasma (P = .01 and .009, respectively). In turbidimetric plasma clotting assays, prolongation of the lag time suggests a defective clotting reaction,21 whereas higher turbidity indicates either thicker fibrin fibers or precipitation of plasma proteins. In this instance, precipitation of plasma proteins by protamine was discounted, as there was no increase in the initial absorbance at higher concentrations of protamine.

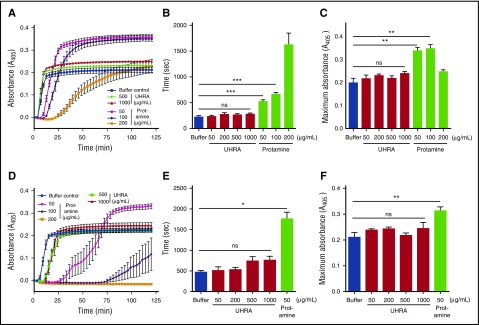

Figure 2.

Plasma clot formation and clot turbidity are unaffected by UHRA. Clot formation in diluted human plasma titrated with varying amounts of UHRA or protamine was investigated using a turbidimetric assay, as described in “Methods.” (A) Turbidity curves (A405nm) were obtained on the addition of TF and CaCl2 (20 mM) to plasma. (B) Lag time (sec) characterizing the time taken for initial protofibril formation during clotting were determined from A. Significant prolongation of lag time was observed by 50 µg/mL protamine (***P < .001). Remarkably, even at 1000 µg/mL UHRA, no significant change in lag time was observed. (C) Maximum absorbance values of plasma clots determined from A formed with UHRA remain unchanged, whereas significant (**P < .005) changes are recorded for clots formed in 50 µg/mL protamine. This indicated that UHRA neither inhibits nor alters fibrin polymerization in plasma. (D) Turbidity curves (A405nm) were obtained on recalcification (20 mM) of plasma. (E) Lag times observed in the presence of UHRA or protamine. No significant change in lag time was observed with UHRA, whereas impaired plasma clotting caused prolongation of lag times at all protamine concentrations studied (*P < .015). (F) Maximum absorbance of plasma clots containing UHRA or protamine. No statistically significant differences in final absorbance values were recorded for the UHRA-containing and polycation-free systems, whereas significant changes (**P < .01) were observed in the 50 µg/mL protamine system. Moreover, no clot was formed at 100 at 200 µg/mL protamine, demonstrating its potent intrinsic anticoagulation activity. A and D report the average turbidity obtained from 3 separate experiments. Absorbance measured at 3-minute intervals is depicted. Results are expressed as the mean ± SE of 9 measurements from 3 independent experiments. Unpaired 2-tailed t tests were performed to determine the significance.

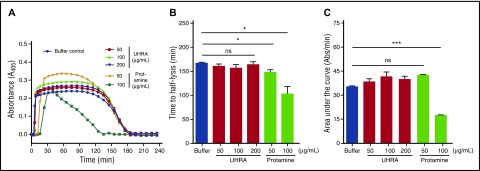

We then used a turbidimetric fibrinolysis assay to investigate the stability of plasma clots formed in the presence of UHRA or protamine. Lysis of plasma clots formed in the presence of UHRA was similar to that observed in the polycation-free control (Figure 3A). Moreover, the clot lysis half-time (CLT50) and the area under the clot lysis curve (AUC) revealed no significant differences between plasma clots formed in the presence or absence of UHRA (Figure 3B-C). In contrast, clots formed in the presence of protamine lyse rapidly compared with the polycation-free control, as shown by CLT50 measurements (Figure 3B) (P = .03). Taken together, these results show that clot formation and lysis are not influenced by the UHRA molecule, but are altered significantly by protamine.

Figure 3.

UHRA does not promote lysis of plasma clots. The influence of UHRA or protamine on human plasma clot lysis was investigated using turbidimetry, as described in “Methods.” (A) Turbidity curves (A405nm) showing lag time, clot formation, and lysis phases; error bars were omitted for clarity. TF and CaCl2 (20 mM) initiated clot formation. Clot lysis was enhanced by adding exogenous tissue plasminogen activator at the initiation of clot formation. Absorbance measured at 2-minute intervals is used for calculating the lag time. The absorbance measured at 8-minute intervals is shown. (B-C) CLT50 and area under the curve values in the presence of UHRA or protamine. Relative to the polycation-free control, clots formed in the presence of UHRA show no significant change in CLT50 and area under the curve values, indicating they are stable and have a normal degradation profile. CLT50 values were reduced significantly (*P < .035) in the presence of 50 and 100 µg/mL protamine, respectively, suggesting faster lysis of these clots compared with the polycation-free control. Results are expressed as the mean ± SE of 6 measurements from 2 independent experiments. Unpaired 2-tailed t tests were performed to determine the significance.

UHRA has a negligible effect on purified fibrin clot and whole-blood clot structure

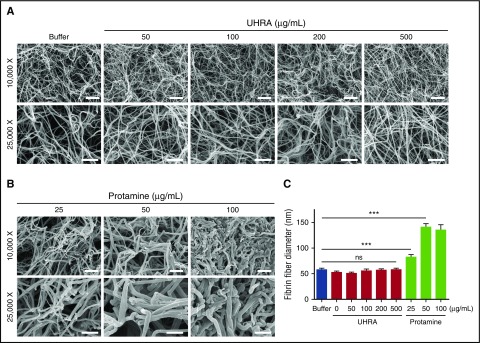

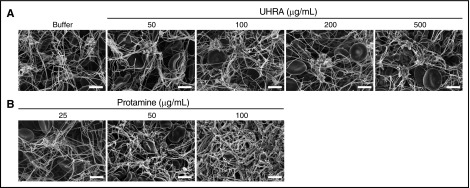

We next investigated the effect of UHRA or protamine on fibrin clot architecture by direct visualization, using SEM. Previous studies show that polycations alter clot structure through nonspecific binding effects.22 As evidence of this, we found that protamine (25 µg/mL) changes clot morphology and increases the mean fiber diameter (P < .001) (Figure 4B-C). The thicker fibrin fibers formed in the presence of protamine correlated with the elevated final turbidities (A405nm) recorded in the corresponding fibrin polymerization assay (Figure 1F). However, as shown in Figure 4A, fibrin clots formed in the presence of UHRA are homogeneous in structure and exhibit no differences from those formed in the buffer control, even at 500 µg/mL UHRA. In addition, UHRA does not change the mean fiber diameter (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

UHRA does not alter purified fibrin clot morphology or fiber diameter. Clots were made by incubating 3 mg/mL human fibrinogen in 3.0 mM CaCl2 plus UHRA or protamine and then initiating clotting with 2.5 National Institutes of Health Units/mL thrombin. Clots were then allowed to mature for 1 hour and processed for SEM imaging. (A) SEM images of fibrin clots formed in the presence of UHRA at different concentrations (50-500 µg/mL) were determined at both low (original magnification ×10 000; scale bar, 2 µm) and high (original magnification ×25 000; scale bar, 1 µm) magnifications. Clot architectures formed in the presence of UHRA are similar to that for the polycation-free control, even up to UHRA concentrations of 500 µg/mL. (B) SEM images of fibrin clots formed in the presence of protamine exhibit altered morphologies compared with the control clot. (C) Fibrin fiber diameters of clots formed in the presence of UHRA or protamine. Fiber diameter is measured from scanning electron micrographs, using ImageJ software. A total of 30 fibers were analyzed. Fibers for size analysis were selected by probing 4 different spots in each image. Data are mean ± SE (n = 30 fibers; measured from 4 images of 2 independent clots). Statistical significance for fiber diameter was determined by comparing the UHRA or protamine-treated group with the control, using a 1-way ANOVA followed by a Dunnett post hoc test. Fibrin fibers formed in the presence of 25 µg/mL protamine are significantly thicker than those in the control clot (***P < .001).

To further delineate the effect of protamine and UHRA on whole blood clot morphology, we prepared clots with varying amounts of either polycation and then analyzed them by SEM. Blood clots prepared in the presence of UHRA showed normal-shaped erythrocytes entrapped in a fibrin mesh, as well as fibrin strands anchored to platelet aggregates similar to buffer control clots (Figure 5A). Blood clots formed in the presence of 25 and 50 µg/mL protamine showed normal clot architecture. However, blood clots formed in the presence of 100 µg/mL protamine, showed thicker and disarrayed fibrin fibers, with no platelet–fibrin networks and platelet aggregates (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Clot characteristics formed in whole blood remain unchanged in the presence of UHRA. Clotting was initiated by recalcifying human whole blood with 11.1 mM CaCl2. Clot samples were then processed for SEM imaging. (A) Clots formed in the presence of 500 µg/mL UHRA did not undergo detectable morphological changes. (B) However, clots formed in the presence of 100 µg/mL protamine showed thicker clot fibers, less platelet aggregates, and complete abnormality in clot architecture. Also, at this concentration of protamine, tiny clots were obtained as a result of the intrinsic anticoagulation effect of protamine. Clotting was inhibited at higher concentrations. Clot images were taken at 2 original magnifications, ×2500 and ×5000. Only images from the original magnification ×5000 are depicted. Scale bar, 4 µm.

The activity and amount of thrombin present in blood influence clot formation and morphology.19 Studies have shown that thrombin activity is affected by protamine.9,23 To test whether UHRA has any influence on thrombin activity, we assessed the ability of thrombin to cleave a chromogenic peptide substrate in the presence of UHRA. We did not observe change in the initial rate of chromophore release from the substrate, suggesting UHRA does not affect thrombin activity (supplemental Figure S7A).

As impaired thrombin generation by protamine is responsible for its intrinsic anticoagulant effect,9 we also evaluated the effect of UHRA on TF-initiated thrombin generation by performing a fluorogenic thrombin generation assay. On clotting of platelet-rich plasma incubated with 100 or 200 µg/mL UHRA, we did not observe any significant changes in endogenous thrombin potential or the amount of thrombin generated (supplemental Figure S7B-D), which is consistent with the normal blood clot morphology observed (Figure 5A). Moreover, whole blood clotting in the presence of UHRA or protamine was evaluated by thromboelastography. Data shown in supplemental Figure S8 corroborate that UHRA does not possess intrinsic anticoagulant activity compared with protamine.

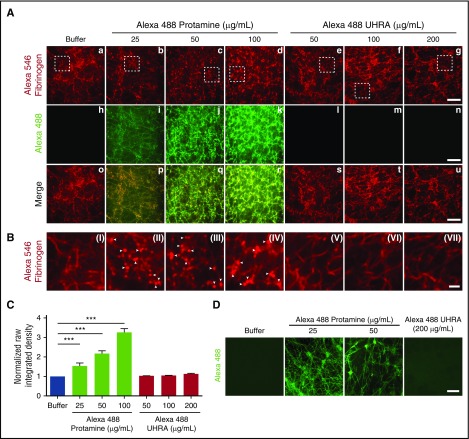

UHRA does not bind or incorporate into purified fibrin or whole blood clots

We next examined whether UHRA is incorporated into clot structures by performing confocal microscopy on fibrin clots and blood clots prepared in the presence of Alexa Fluor 488–labeled UHRA or protamine. Fibrinogen was labeled with Alexa Fluor 546 (red color). Results are summarized in Figure 6. We observed that the architecture of clots formed in the presence of increasing amounts of UHRA (Figure 6Ae-g, 6BV-VII) was quite similar to the control clot (Figure 6Aa, BI). In contrast, clots formed in the presence of protamine showed fibrin(ogen) aggregates that appear as numerous distinct dots (Figure 6Ab-d, BII-IV; indicated by white arrowheads). In addition, protamine was incorporated throughout the fibrin structure in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 6Ai-k, 6C) and exhibited colocalization in both channels (Figure 6Ap-r). No incorporation of UHRA was observed even at 200 μg/mL, with results comparable to the buffer control (Figure 6Al-n, 6C).

Figure 6.

UHRA does not bind or incorporate into purified fibrin, blood clots, or other clot components. Clots for confocal microscopy were prepared as described in the supplemental Data (confocal microscopy of fibrin and blood clots). Briefly, human fibrinogen 3 mg/mL, of which 2% was Alexa Fluor 546–fibrinogen, was mixed with UHRA or protamine (both conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488), and clotting was initiated with thrombin 2.5 National Institutes of Health Units/mL and 3 mM CaCl2. (A) The top panel (red channel) shows confocal micrographs of fibrin clots formed from Alexa Fluor 546–labeled fibrinogen. The middle panel (green channel) shows confocal micrographs of protamine or UHRA localization within fibrin clots. Fibers of clots (i-k) formed in the presence of protamine exhibit green fluorescence, indicating binding of protamine to fibrin fibers. Green signal is absent in clots formed in the presence of UHRA (l-n), suggesting no binding or incorporation of UHRA into fibrin fibers. The lower panel (merge) shows overlay of images from the red and green channels confirming the colocalization of fibrin and protamine. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Magnified images from the white boxes shown in the red channel. Visual inspection of clots (II-IV) formed in the presence of Alexa Fluor 488–labeled protamine reveals different fibrin architecture (presence of more compact and round fibrin (ogen) aggregates indicated by white arrowheads) compared with the control clot (I). No architectural differences are observed for clots formed in the presence and absence of UHRA (V-VII). Scale bar, 2μm. (C) Normalized raw integrated density (sum of all pixel intensities normalized to polycation-free buffer) of the green channel analyzed using FIJI. Depicted are mean values ± SD with 10 or more randomly acquired images analyzed per condition. The P values were determined using the unpaired t test. (***P < .001). (D) Representative confocal micrographs of whole blood clots formed in the presence of UHRA or protamine. No green fluorescence is observed in blood clots formed in the presence of UHRA. This shows that UHRA does not interact or incorporate into the clot components. In contrast, fluorescence from protamine containing blood clot fibers and platelet aggregates/clumps show binding of protamine to these clot components. Scale bar, 10 µm.

Similar findings were obtained for whole blood clots, where UHRA showed minimal incorporation into clots. Clots formed in the presence of protamine fluoresce green, with a pattern suggesting protamine binding to both fibrin fibers and platelet aggregates (Figure 6D). Taken together, the results indicate that UHRA does not bind to or incorporate within fibrin, blood clots, or their structural components.

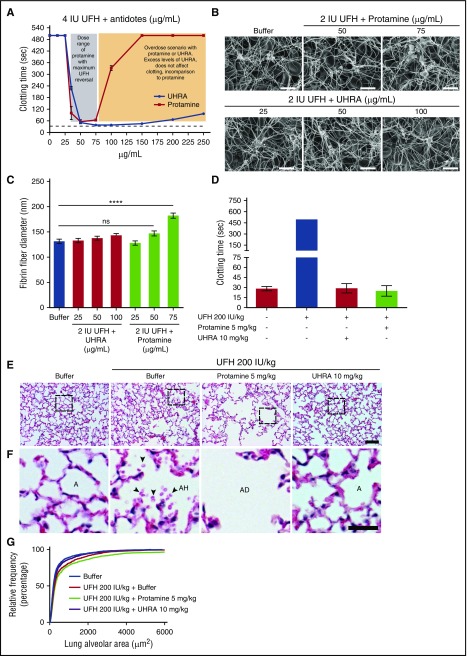

UHRA reverses anticoagulant activity of UFH without lung injury and alteration in clot morphology

To avoid heparin-induced bleeding complications in postoperative patients, heparin is neutralized by administering protamine.24 However, to restore hemostasis, the optimal protamine dose must be administered as excess heparin, or excess protamine may cause bleeding.25 To test the effect of excess UHRA levels on heparin neutralization and clotting, we simulated an antidote overdose scenario by titrating UHRA or protamine into heparinized plasma (4 IU/mL UFH, final). Effects on coagulation were assessed by measuring changes in the activated thromboplastin time assay. Results show that UHRA (50-250 µg/mL) normalized the elevated clotting time induced by heparin, with excess UHRA levels showing no adverse effect on clotting. Protamine, as is known, showed a narrow therapeutic window, with excess protamine levels impairing clotting (Figure 7A). In addition, we show that UHRA can completely neutralize anticoagulation activity of low-MW heparin (tinzaparin) compared with protamine, which is only partially effective (supplemental Figure S9).

Figure 7.

UHRA reverses anticlotting activity of UFH with no adverse effect on lung ultrastructure or clot morphology. Neutralization of UFH by UHRA or protamine was studied by activated partial thromboplastin time assay in heparinized human plasma. (A) UHRA neutralizes UFH (4 IU/mL) over a wide range of concentrations. Conversely, excess protamine impairs clotting. (B) Morphology of clots formed after neutralization of UFH with UHRA or protamine analyzed by SEM. Clot micrographs obtained in the presence of UHRA revealed normal morphology in comparison with the buffer control clot. Clot images at original magnification ×5000 are depicted. Scale bar, 5 μm. (C) Thickness of clot fibers was measured from clot micrographs using ImageJ. Fibers for size analysis were selected by probing 4 different spots in each image. Data are mean ± SE (n = 30 fibers, measured from 2 images of each clot). Fibrin fibers formed in the presence of 75 µg/mL protamine are significantly thicker than those in the buffer control clot (1-way ANOVA followed by a Dunnett post hoc test; ****P < .0001). Size of clot fibers obtained after neutralizing UFH with UHRA at all tested concentrations is comparable to buffer control. (D) In vivo neutralization of UFH activity were studied in mice by injecting UFH 200 IU/kg intravenously (via tail-vein), followed by UHRA (10 mg/kg) or protamine (5 mg/kg). aPTT confirms neutralization of UFH activity by antidotes. (E-F) Histopathological sections of lungs after heparin neutralization were obtained from buffer and UHRA-treated groups, which were comparable. However, in the protamine-treated group, significant damage to lung alveolar structure was observed. Lungs from the heparin-only group showed mild hemorrhage (presence of red blood cells in alveolar space). Scale bar, 50 μm. In magnified images: scale bar, 20 μm. Hematoxylin and eosin stain for panels E-F. A, alveolar space; AD, alveolar disruption; AH, alveolar hemorrhage. (G) Relative cumulative distribution of lung alveolar area. Depicted are values measured from 144 images from the lungs of 8 mice (2 mice per treatment group). Measurements confirm enhancement of alveolar area in the protamine-treated group compared with the buffer control.

Using turbidimetric and clot elastic modulus studies, other investigators have shown that clots formed after neutralization of heparin with excess protamine possess altered and weaker clot structure.26 We therefore analyzed the morphology of blood clots obtained after neutralization of UFH (2 IU/mL, final) with UHRA or protamine, using SEM. Visual inspection of clot micrographs revealed that at all tested concentrations of UHRA, clots exhibited normal architecture (Figure 7B). The normal clot morphology observed could be considered as an indirect measure of anticoagulant neutralization because clots were not formed in samples treated with UFH only. Also, clots formed in the presence of UHRA possess fiber diameters that are comparable to the buffer control (Figure 7C). Interestingly, clots formed with excess protamine (75 µg/mL) contain significantly thicker fibrin fibers compared with the buffer control (Figure 7C) (P < .0001), possibly as a result of binding and incorporation of protamine into clot fibers. To show that protamine could incorporate into clots even in the presence of UFH, we performed confocal microscopy on blood clots obtained after neutralizing 2 IU /mL UFH with Alexa Fluor 488–labeled UHRA or protamine. Results show that in either heparinized or nonheparinized blood, protamine binds to clot fibers or its components (supplemental Figure S10).

Finally, we investigated the effect of heparin neutralization by UHRA or protamine on mouse lung morphology. Lung injury is a common postoperative complication observed in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB).27 Although the etiology of CPB-induced lung injury is multifactorial,28 studies suggest that administration of protamine to neutralize heparin after CPB may contribute adverse pulmonary events such as noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, characterized by loss of alveolocapillary membrane integrity.29,30 Therefore, we administered UFH (200 IU/kg) intravenously, followed by UHRA (10 mg/kg) or protamine (5 mg/kg) intravenously, into mice. Clotting assays revealed that both UHRA and protamine neutralized the anticoagulant activity of UFH (Figure 7D). In the UFH-only group, we observed mild hemorrhage characterized by the presence of red blood cells in the alveolar space. Consistent with clinical manifestations, in the protamine-treated group, we observed disruption of alveolar membrane and subsequent enlargement of alveolar sacs (Figure 7E-F). Quantification of the alveolar area in those protamine-treated mice showed significant alveolar space enlargement due to loss of membrane integrity (P < .0001) (Figure 7G). In contrast, normal lung ultrastructure was observed in the UHRA-treated group, which is comparable to the buffer-treated group (Figure 7E-F).

Discussion

Hemocompatible polycations that can specifically bind and inhibit polyanionic modulators of hemostasis, such as heparins and polyP, with negligible adverse effects could provide improved treatment of disorders of hemostasis and thrombosis. However, previously proposed polycations are nonspecific, binding to anionic plasma proteins such as fibrinogen in ways that lead to adverse effects.10,12,13 We are therefore working toward developing cationic inhibitors with improved specificity and reduced toxicity. Combined with our previous studies,14,15 the results shown here demonstrate that UHRA molecules can be safe and effective.

Although UHRA relies on CBGs for activity, these ligands are engineered within the mPEG brush that acts to limit nonspecific binding and the associated adverse effects while retaining specificity for highly polyanionic heparins and polyP.14,15 Here we show that a UHRA molecule designed in this manner has minimal influence on blood proteins, clotting, or clot morphology, even at concentrations 20-fold and 10-fold higher than required for heparin14 and polyP15 inhibitory activity, respectively.

The interaction of UHRA and fibrinogen was investigated because the latter is known to adsorb onto hydrophobic and positively charged surfaces31 and polycationic molecules such polyethyleneimine.16 Our fluorometric and CD data show that UHRA does not interact with or induce fibrinogen conformational changes, even at high concentrations. The mPEG brush layer creates steric stabilization effects32 capable of preventing nonspecific binding to the underlying CBGs, and therefore serves to effectively prevent fibrinogen binding to the polycationic UHRA molecule. Intermolecular ion pairs formed with the relatively low density of anionic groups within fibrinogen are not sufficient to overcome the energetic penalty of brush compression,33 whereas our ITC data show that high-affinity binding of heparin and polyP is retained as a result of more optimal formation of intermolecular ion pairs.

The effect of the unique manner in which cationic ligands are presented within UHRA molecules is made clear through our comparative studies with the conventional unshielded polycation protamine. Clotting occurs through thrombin-mediated polymerization of fibrinogen to fibrin.34 Binding of exogenous molecules such as antibodies or synthetic polymers to fibrinogen can either enhance or inhibit fibrin polymerization, thereby affecting clot stability.35-38 This stability depends on clot architecture, which is affected by thrombin and fibrinogen concentrations, pH, and ionic strength.19,34 A polycation that acts to perturb any of these factors can therefore influence clotting. We found from turbidity profiles of fibrin clots that protamine addition causes increased clot turbidity, possibly as a result of nonenzymatic fibrinogen polymerization, incorporation of protamine into fibrinogen/fibrin, and/or polycation-induced precipitation of fibrinogen. SEM images of fibrin clots showed that fibrin structures formed in the presence of protamine were thicker and the overall clot morphology was markedly different than the polycation-free control. In plasma clotting assays, higher concentrations of protamine delayed clotting and showed anticoagulant properties. Protamine also greatly elevated turbidity, possibly by impairing thrombin generation, which is known to result in formation of thick clot fibers,9,10 as was observed here. Clot architecture was considerably altered with increasing protamine concentrations, most notably observed above 50 µg/mL.

Turbidimetric assays were used to show that clots formed in the presence of protamine exhibited enhanced fibrinolysis. This enhanced clot lysis might occur through several possible mechanisms. Our confocal images of purified fibrin and blood clots show that protamine is incorporated within the clot structure and promotes abnormal clot architecture (electron microscopy images shown in Figures 4 and 5) that could facilitate lysis. Clots containing mostly thicker fibers formed in the presence of protamine are more susceptible to lysis than clots with thinner fibers.34 Alternatively, polycationic surfaces can localize plasminogen, and thereby enhance clot lysis.39,40 Regardless of mechanism, our results confirm and help explain why unshielded polycations such as protamine, most notably at concentrations higher than 30 µg/mL, adversely affect blood coagulation. However, Ni Ainle et al have shown that protamine (in the absence of heparin) 10 µg/mL is enough to prolong the activated partial thromboplastin time and prothrombin time. This clearly demonstrates that protamine at lower concentrations induces deleterious effects.9 In CPB, protamine (<50 µg/mL) is administered to neutralize UFH.9,41 Protamine dosing correlates with bleeding during CPB,42 and delayed bleeding problems associated with CPB are linked to fibrinolysis instigated by protamine.17 Our studies suggest that protamine-induced changes in clot architecture, possibly in combination with protamine-mediated changes in plasminogen localization, may serve to accelerate degradation of nascent clots formed on heparin neutralization, thereby increasing the risk for hemorrhagic complications.

In general, 1 mg protamine neutralizes ∼100 units UFH.43 To achieve hemostasis after cardiac surgeries, optimal dosing of protamine, based on plasma heparin concentration, has to be administered; otherwise, excess UFH or protamine may result in bleeding.43 Imbalances in heparin–protamine titration as a result of unfavorable pharmacokinetics and/or nonspecific binding to plasma proteins exhibited by UFH and protamine may yield a relative “overdose” of heparin or protamine in surgical patients.43,44 Our heparin–UHRA titration in plasma revealed that unlike protamine, UHRA neutralizes heparin anticoagulant activity over a wide range of concentrations. Most important, UHRA overdose did not impair clotting. On the basis of our ex vivo results shown in this article, and from our previous studies,14 we can posit that to completely neutralize UFH 4 IU/mL in blood (Figure 7A), we would require a final concentration of 50 µg/mL UHRA. Thus, to neutralize UFH 5000 IU, we would require ∼62.5 mg UHRA.14

We further show that UHRA reverses anticoagulant activity of UFH in mice without causing lung toxicity. Mice that received protamine for heparin neutralization showed significant lung damage with characteristic alveolar membrane damage. Protamine-associated noncardiogenic pulmonary edema occurs in 0.2% of patients with CPB with 30% mortality.45 The exact mechanism for protamine-induced noncardiogenic pulmonary edema is not known. However, complement activation by heparin–protamine complexes and subsequent activation of neutrophils in lungs release proteolytic enzymes that can disintegrate lung ultrastructure,46 whereas unshielded cationic charge in protamine can cause pulmonary endothelial cell injury.46

Hemostatic complications and organ toxicity are avoided with UHRA technology. UHRA binds both UFH and polyP with high affinity, but shows no discernable interaction with fibrinogen or clot components. Normal clot formation, architecture, strength, and fibrinolysis kinetics are therefore preserved in the presence of UHRA, and this blood compatibility aligns with the lack of toxicity of UHRA in rodents.14,15 The findings reported here therefore further demonstrate the potential of UHRA as a next-generation antidote for UFH after CPB.

Finally, information from this study could be applied to design UHRA with an extended safety profile and inhibition specificity. Additional treatment opportunities may therefore arise, for example, through screening of UHRA libraries to identify lead molecules to dismantle or neutralize detrimental histone–DNA complexes implicated in sepsis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Donald E. Brooks and Cedric J. Carter at the University of British Columbia Centre for Blood Research for expert advice; Derrick Horne at the University of British Columbia Bioimaging facility for assistance in SEM imaging; Irina Chafeeva, Scott Meixner, Srinivas Abbina, Anilkumar Parambath, Iren Constantinescu, Nester Solis, Brauna Culibrk, and Rolinda Carter at the University of British Columbia Centre for Blood Research for technical suggestions; and Carmen Cheng and Ava McHugh at the University of British Columbia Centre for Comparative Medicine and Erin Limber at the University of British Columbia modified barrier facility for assistance in animal studies. The authors also thank LMB Macromolecular Hub at the University of British Columbia Centre for Blood Research for the use of research facilities. Finally, thanks to all blood donors who participated in this study.

M.T.K. is supported by a Centre for Blood Research graduate student award. J.N.K., C.A.H., and E.M.C. acknowledge funding from Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada, and J.H.M. acknowledges funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant R01 HL047014). J.N.K. is a recipient of a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Career Scholar Award. C.A.H. and E.M.C. are recipients of a Canada Research Chair. E.L.G.P. has funded this work through a Canadian Heart and Stroke Foundation Grant-in-Aid.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: M.T.K. designed and performed experiments, analyzed results, and wrote the manuscript; L.A., P.R.K., and B.F.L.L. performed experiments, analyzed results, and edited the manuscript; R.A.S., F.I.R., E.M.C., and E.L.G.P. analyzed results and edited the manuscript; J.H.M. contributed to reagents and edited the manuscript; and C.A.H. and J.N.K. designed experiments, analyzed results, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.N.K. and R.A.S. hold a patent for the use of UHRA compounds as antidotes for heparin-based anticoagulants (US 8519189). M.T.K., R.A.S., J.H.M., and J.N.K. are coinventors on pending patent applications for use of UHRA compounds as antithrombotic drugs and for clinical and diagnostic uses of polyphosphate (WO 2015179958). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for R.A.S. is Inter University Centre for Biomedical Research & Super Specialty Hospital, Mahatma Gandhi University Campus, Thalappady, Kottayam, India.

Correspondence: Jayachandran N. Kizhakkedathu, Centre for Blood Research, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z3, Canada; e-mail: jay@pathology.ubc.ca.

References

- 1.Raskob GE, Angchaisuksiri P, Blanco AN, et al. ; ISTH Steering Committee for World Thrombosis Day. Thrombosis: a major contributor to global disease burden. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2014;40(7):724-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crowther MA, Warkentin TE. Bleeding risk and the management of bleeding complications in patients undergoing anticoagulant therapy: focus on new anticoagulant agents. Blood. 2008;111(10):4871-4879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kannemeier C, Shibamiya A, Nakazawa F, et al. . Extracellular RNA constitutes a natural procoagulant cofactor in blood coagulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(15):6388-6393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith SA, Mutch NJ, Baskar D, Rohloff P, Docampo R, Morrissey JH. Polyphosphate modulates blood coagulation and fibrinolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(4):903-908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, et al. . Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(36):15880-15885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith SA, Choi SH, Collins JNR, Travers RJ, Cooley BC, Morrissey JH. Inhibition of polyphosphate as a novel strategy for preventing thrombosis and inflammation. Blood. 2012;120(26):5103-5110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park KW. Protamine and protamine reactions. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2004;42(3):135-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sogawa M, Mohammad SF. Involvement of fibrinogen in protamine-induced pulmonary hypertension. J Surg Res. 1997;73(1):80-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ni Ainle F, Preston RJS, Jenkins PV, et al. . Protamine sulfate down-regulates thrombin generation by inhibiting factor V activation. Blood. 2009;114(8):1658-1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart GJ, Niewiarowski S. Nonenzymatic polymerization of fibrinogen by protamine sulfate. An electron microscope study. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;194(2):462-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain S, Pitoc GA, Holl EK, et al. . Nucleic acid scavengers inhibit thrombosis without increasing bleeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(32):12938-12943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain K, Kesharwani P, Gupta U, Jain NK. Dendrimer toxicity: Let’s meet the challenge. Int J Pharm. 2010;394(1-2):122-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones CF, Campbell RA, Brooks AE, et al. . Cationic PAMAM dendrimers aggressively initiate blood clot formation. ACS Nano. 2012;6(11):9900-9910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shenoi RA, Kalathottukaren MT, Travers RJ, et al. . Affinity-based design of a synthetic universal reversal agent for heparin anticoagulants. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(260):260ra150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Travers RJ, Shenoi RA, Kalathottukaren MT, Kizhakkedathu JN, Morrissey JH. Nontoxic polyphosphate inhibitors reduce thrombosis while sparing hemostasis. Blood. 2014;124(22):3183-3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong D, Jiao Y, Zhang Y, et al. . Effects of the gene carrier polyethyleneimines on structure and function of blood components. Biomaterials. 2013;34(1):294-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen VG. Protamine enhances fibrinolysis by decreasing clot strength: role of tissue factor-initiated thrombin generation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(5):1720-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai BFL, Zou Y, Yang X, Yu X, Kizhakkedathu JN. Abnormal blood clot formation induced by temperature responsive polymers by altered fibrin polymerization and platelet binding. Biomaterials. 2014;35(8):2518-2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolberg AS. Thrombin generation and fibrin clot structure. Blood Rev. 2007;21(3):131-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Min J, Meng-Xia X, Dong Z, et al. . Spectroscopic studies on the interaction of cinnamic acid and its hydroxyl derivatives with human serum albumin. J Mol Struct. 2004;692(1-3):71-80. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter AM, Cymbalista CM, Spector TD, Grant PJ; EuroCLOT Investigators. Heritability of clot formation, morphology, and lysis: the EuroCLOT study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(12):2783-2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amelot AA, Tagzirt M, Ducouret G, Kuen RL, Le Bonniec BF. Platelet factor 4 (CXCL4) seals blood clots by altering the structure of fibrin. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(1):710-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cobel-Geard RJ, Hassouna HI. Interaction of protamine sulfate with thrombin. Am J Hematol. 1983;14(3):227-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulman S, Bijsterveld NR. Anticoagulants and their reversal. Transfus Med Rev. 2007;21(1):37-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radulovic V, Laffin A, Hansson KM, Backlund E, Baghaei F, Jeppsson A. Heparin and Protamine Titration Does Not Improve Haemostasis after Cardiac Surgery: A Prospective Randomized Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0130271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carr ME Jr, Carr SL. At high heparin concentrations, protamine concentrations which reverse heparin anticoagulant effects are insufficient to reverse heparin anti-platelet effects. Thromb Res. 1994;75(6):617-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark SC. Lung injury after cardiopulmonary bypass. Perfusion. 2006;21(4):225-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng CSH, Wan S, Yim APC, Arifi AA. Pulmonary dysfunction after cardiac surgery. Chest. 2002;121(4):1269-1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urdaneta F, Lobato EB, Kirby RR, Horrow JC. Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema associated with protamine administration during coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Clin Anesth. 1999;11(8):675-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ege T, Arar C, Canbaz S, et al. . The importance of aprotinin and pentoxifylline in preventing leukocyte sequestration and lung injury caused by protamine at the end of cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;52(1):10-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostuni E, Chapman RG, Holmlin ER, Takayama S, Whitesides GM. A survey of structure-property relationships of surfaces that resist the adsorption of protein. Langmuir. 2001;17(18):5605-5620. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeon SI, Lee JH, Andrade JD, Degennes PG. Protein surface interactions in the presence of polyethylene oxide. 1. Simplified theory. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1991;142(1):149-158. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adamczyk Z, Cichocki B, Ekiel-Jeżewska ML, Słowicka A, Wajnryb E, Wasilewska M. Fibrinogen conformations and charge in electrolyte solutions derived from DLS and dynamic viscosity measurements. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;385(1):244-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weisel JW. Structure of fibrin: impact on clot stability. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl 1):116-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheiner T, Jirousková M, Nagaswami C, Coller BS, Weisel JW. A monoclonal antibody to the fibrinogen γ-chain alters fibrin clot structure and its properties by producing short, thin fibers arranged in bundles. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1(12):2594-2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carr ME Jr, Powers PL, Jones MR. Effects of poloxamer 188 on the assembly, structure and dissolution of fibrin clots. Thromb Haemost. 1991;66(5):565-568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carr ME, White GC II, Gabriel DA. Platelet factor 4 enhances fibrin fiber polymerization. Thromb Res. 1987;45(5):539-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carr ME Jr, Cromartie R, Gabriel DA. Effect of homo poly(L-amino acids) on fibrin assembly: role of charge and molecular weight. Biochemistry. 1989;28(3):1384-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McClung WG, Clapper DL, Hu SP, Brash JL. Lysine-derivatized polyurethane as a clot lysing surface: conversion of adsorbed plasminogen to plasmin and clot lysis in vitro. Biomaterials. 2001;22(13):1919-1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodhouse KA, Weitz JI, Brash JL. Lysis of surface-localized fibrin clots by adsorbed plasminogen in the presence of tissue plasminogen activator. Biomaterials. 1996;17(1):75-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Butterworth J, Lin YA, Prielipp RC, Bennett J, Hammon JW, James RL. Rapid disappearance of protamine in adults undergoing cardiac operation with cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(5):1589-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butterworth J, Lin YA, Prielipp R, Bennett J, James R. The pharmacokinetics and cardiovascular effects of a single intravenous dose of protamine in normal volunteers. Anesth Analg. 2002;94(3):514-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia DA, Baglin TP, Weitz JI, Samama MM; American College of Chest Physicians. Parenteral anticoagulants: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e24S-43S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khan NU, Wayne CK, Barker J, Strang T. The effects of protamine overdose on coagulation parameters as measured by the thrombelastograph. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27(7):624-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brooks JC. Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema immediately following rapid protamine administration. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33(9):927-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang SW, Voelkel NF. Charge-related lung microvascular injury. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139(2):534-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]