Abstract

Excoriation (skin-picking) disorder (SPD) is a disabling, under-recognized condition in which individuals repeatedly pick at their skin, leading to noticeable tissue damage. There has been no examination as to whether individuals with SPD have different pain thresholds or pain tolerances compared to healthy counterparts. Adults with SPD were examined on a variety of clinical measures including symptom severity and functioning. All participants underwent the cold pressor test. Heart rate, blood pressure, and self-reported pain were compared between SPD participants (n=14) and healthy controls (n=14). Adults with SPD demonstrated significantly dampened autonomic response to cold pressor pain as exhibited by reduced heart rate compared to controls (group x time interaction using repeated ANOVA F=3.258, p<0.001). There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of overall pain tolerance (measured in seconds), recovery time, or blood pressure. SPD symptom severity was not significantly associated with autonomic response in the patients. In this study, adults with SPD exhibited a dampened autonomic response to pain while reporting pain intensity similar to that reported by the controls. The lack of an autonomic response may explain why the SPD participants continue a behavior that they cognitively find painful and may offer options for future interventions.

1. Introduction

Excoriation (skin-picking) disorder (SPD) is a disabling, under-recognized condition in which individuals repeatedly pick at their skin, leading to noticeable tissue damage (APA, 2013). Psychosocial impairment, reduced quality of life, and medical problems such as infections are common among individuals with SPD (Flessner et al., 2006; Tucker et al., 2011). Despite its relatively high prevalence (with an estimated lifetime prevalence rate of 1.4% to 5.4% for clinically meaningful picking that results in distress or functional impairment) (Hayes et al., 2009; Keuthen et al., 2010), SPD remains poorly understood with limited data regarding underlying pathophysiology and optimal treatments (Grant et al., 2012).

While skin picking would likely be painful for healthy individuals, those with SPD report picking episodes lasting several hours, resulting in significant skin damage (Odlaug and Grant, 2008; Tucker et al., 2011), which may suggest changes in pain perception – such as loss of pain sensitivity. To date, no research has examined whether individuals with SPD experience pain differently from healthy controls. In related research, Christenson and colleagues (1994) found that adults with trichotillomania (a related body focused repetitive behavior disorder) (Grant and Stein, 2014) exposed to a steadily increasing pressure stimulus to the fingertip failed to show hypoalgesia. Similarly, trichotillomania volunteers in an experimental hair-pulling task reported levels of physical pain comparable to healthy controls (Diefenbach et al., 2008). The previous research in trichotillomania is valuable, but skin picking and hair pulling may differ in terms of pain. While plucking a hair may be momentarily discomforting, picking into the skin would seem to produce greater pain and the pain would likely endure even after the picking ends and the skin is healing. Therefore, the question remains as to whether adults with SPD have different pain thresholds, pain tolerances, or autonomic responses to painful stimuli, as contrasted to people without this disorder.

One means of understanding pain perception is via the cold pressor test. The cold pressor test requires participants to immerse their hands in ice-cooled water until the task becomes too uncomfortable. Although the pain circuitry of SPD has not been previously examined, a general understanding of pain suggests that noxious cold cutaneous sensations are recognized primarily by the cold-sensitive ion channel TRPM8 before sensory signal transduction (Winchester et al., 2014). Functional neuroimaging data reveals that noxious cold stimulation applied to the upper limbs of healthy subjects was associated with activation of the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex, regions classically implicated in aversive emotional processing (Duerden and Albanese, 2013). Intriguingly, limited imaging and cognitive data implicate the anterior cingulate cortex in the pathophysiology of SPD (Odlaug et al., 2016).

Using the cold pressor test, and based on the clinical data regarding SPD, we hypothesized that adults with SPD would exhibit a dampened autonomic response to pain compared to healthy controls. In addition, we hypothesized that adults with SPD would subjectively report less discomfort when undergoing the cold pressor task and that pain sensitivity significantly and negatively correlated with worse skin picking symptom severity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Men and women aged 18– 65 with a current primary diagnosis of SPD, based on DSM-5 criteria, were recruited by media advertisements, referrals, and in person at the Trichotillomania Learning Center (TLC) Foundation for Body Focused Repetitive Behaviors annual conference.

Age and gender-matched healthy controls were recruited by word of mouth and through poster and newspaper advertisements. All control group participants were free of any current psychiatric disorder, as measured using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Inventory (MINI) (Sheehan, et al., 1998), and Minnesota Impulse Disorder Inventory (MIDI) (Grant, 2008).

Exclusion criteria across all participants included: 1) history of Raynaud’s phenomenon; 2) history of cardiovascular disorder; 3) open cuts or sores on the hands; 4) history of fainting or seizures; 5) fracture of the limb to be submersed; 6) history of frostbite; and (7) an inability to understand or undertake the procedures or an inability to provide written informed consent.

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Chicago approved the study and consent procedures, which followed the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical principles for medical research involving human participants. After a complete description of study procedures, participants were given the opportunity to ask questions and provided voluntary informed consent using the IRB-approved consent form. Subjects were compensated with $10 cash at the end of the visit.

2.2. Procedures

Demographics and clinical features of SPD were assessed with an unpublished semi-structured interview. The semi-structured interview included DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for SPD as well as questions regarding SPD’s phenomenology. Psychiatric comorbidity was assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (First, et al., 1997).

Skin picking severity measures were: (i) The Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale modified for Neurotic Excoriation (NE-YBOCS) (Arnold et al., 1999); and (ii) the Skin Picking Symptom Assessment Scale (SP-SAS). The NE-YBOCS is a 10-item scale that assesses picking symptoms during the last seven days. The SP-SAS is a self-report scale of skin picking symptoms over the past seven days (Grant et al., 2007). Both scales have demonstrated good preliminary reliability and validity (Grant et al., 2007).

We examined pain perception using the Cold Pressor Test (CPT). The CPT is a reliable and valid pain induction method (Edens and Gil, 1995) that requires participants to submerge their hand in a 85-fluid ounce container filled with ice water at a temperature between 0-4° C. Participants immersed the non-dominant hand in the water bath to just above the wrist and were instructed to keep their hand open (rather than in a closed fist position) while it was in the water. Before immersion, participants were told to keep the hand in the water until the pain became intolerable or until the cutoff time of 3 minutes was reached. During the task, subjects rated their pain at 15-second intervals using an adapted version of the valid and reliable self-report Wong-Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale (Al’Absi et al., 2004; Aziato et al., 2015; Wong and Baker, 1988). Pain was rated on a scale from 0 (not painful at all) to 100 (extremely painful). Intermediate ratings marked on the Likert scale include 25 (somewhat painful), 50 (moderately painful), and 75 (very painful). Pain ratings were displayed on a large poster in a line from 0-100. Each intermediate rating included a visual representation of pain associated with that rating. Latency to pain tolerance (when the hand was voluntarily withdrawn) was measured with a stopwatch in seconds. Heart rate and blood pressure were recorded serially using an automated digital device: heart rate every 15 seconds, and blood pressure at baseline and at point of hand withdrawal. Because the CPT may cause physical discomfort or psychological stress, volunteers were free to discontinue the task at any point.

2.3. Data Analysis

Demographic and unitary CPT measures were compared between the SPD and the control groups using one way analysis of variance or equivalent non-parametric tests where appropriate. For serial CPT measures, data were entered into repeated measures analyses of variance; effects of disease severity were evaluated by entering these parameters as potential covariates. Where CPT data were not available for a subject at a given time point due to attrition, the appropriate group mean was entered into the model. Results were reported with significance defined as p<0.05 two-tailed, uncorrected. Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 22; IBM, Armonk, NY).

3. Results

There were no significant demographic differences between participants with SPD (N = 14, Mage = 32.0 years, SD = 11.0, 64.3% women) and healthy controls (N = 14, Mage = 31.0 years, SD = 7.8, 78.6% women). The mean NE-YBOCS and SP-SAS scores for the SPD participants were 19.7 and 27.5, respectively, which correlates to moderate severity of symptoms. The mean age of picking onset for those with SPD was 14.1 years. 71.4% (N=10) picked from more than one part of their body (e.g. face (50%, N=7), fingers (28.6%, N=4), arms (35.7%, N=5), legs (28.6%, N=4)). Because the cold pressor task could induce pain in the hand area, SPD individuals in this study who picked at their hands or fingers also picked from other body areas and did not have open excoriations on their hands at the time of testing. All 14 of the SPD group picked daily for at least one hour each day and all had noticeable excoriations. The most commonly cited triggers for picking included: boredom, stress, and sedentary activities.

3.1. Cold Pressor Test

The mean time that the cold water was tolerated (i.e. time spent before removing hand from the water) was 120.14 seconds in the SPD group compared to 145.71 seconds in the control group (t=-1.175, p=.250). In addition the percentage of individuals with SPD who left their hands in the water for the entire 3 minute period was 50.0% compared to 57.1% of the control group (Fisher’s Exact Test, p=1.000).

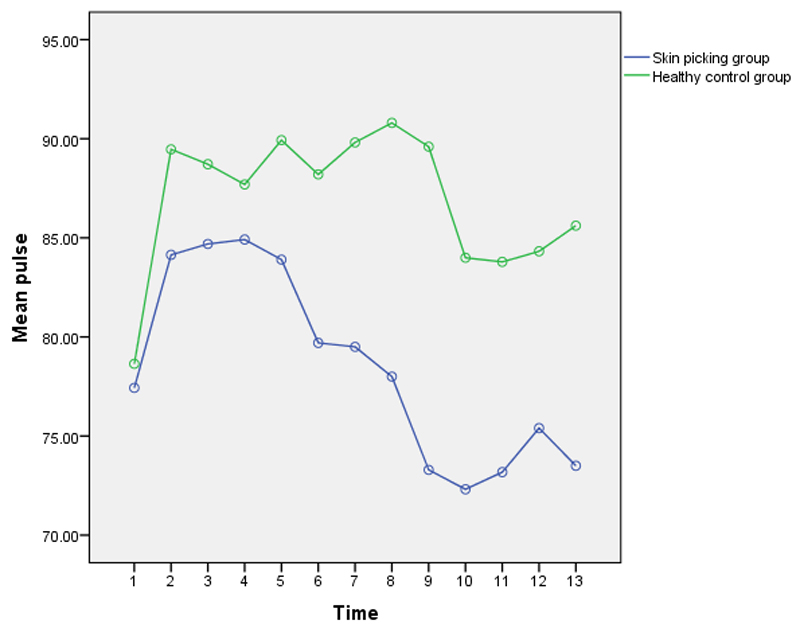

The mean heart rate at each time point for each group is shown in Figure 1. There was a main effect of time (F=8.494, p<0.001), a main effect of group (F=7.565, p=0.011), and a significant group x time interaction (F=3.258, p<0.001).

Figure 1. Mean heart rate (beats per minute) during the Cold Pressor Test in skin picking disorder compared to controls.

The SPD group showed significantly dampened autonomic response versus the controls. Time 1 represents baseline, and Time 13 represents +180 seconds.

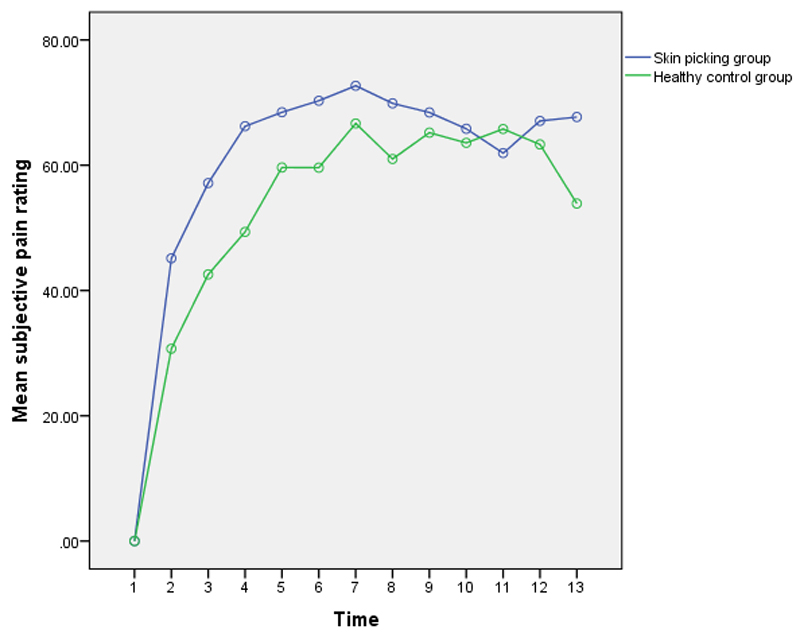

Mean pain ratings for the SPD and control groups at each time point are shown in Figure 2. There was a main effect of time (F=40.723, p<0.001), but no main effect of group (p>0.10), nor was there a significant group by time interaction (p>0.20).

Figure 2. Mean pain ratings (maximum 100) during the Cold Pressor Test in skin picking disorder versus controls.

Adults with SPD did not differ from controls in their subjective pain ratings. Time 1 represents baseline, and Time 13 represents +180 seconds.

The mean (standard error) blood pressure in the skin picking and control groups respectively were as follows: at baseline 133.6/82.3 [4.0/3.9], 123.0/83.5 [4.2/4.0]; at point of hand withdrawal 139.4/89.7 [3.9/2.8], 136.6/91.2 [4.0/2.9]. For systolic blood pressure, there was a main effect of time (F=11.678, p=0.002), but not of group (p>0.20), nor was there a significant group x time interaction (p>0.10). For diastolic blood pressure, there was a main effect of time (F=12.309, p=0.002) but not of group (p>0.20), nor was there a significant group x time interaction (p>0.20).

The mean pain recovery time did not differ significantly between the groups (mean [SD] 121.6 [99.8] sec in patients vs 66.6 [37.3] sec in controls; p=0.125).

When measures of disease severity (NE-YBOCS, SP-SAS total scores) were entered into the repeated measures ANOVAs for heart rate, they did not have any statistically significant main effects or significant interactions with time (all p>0.09).

4. Discussion

In this study, and consistent with our hypothesis, adults with SPD exhibited a dampened autonomic response to pain during the CPT compared to control participants. SPD participants however rated their pain perception similar to the healthy controls. Taken together, these findings suggest that skin picking is associated with lower cold pain sensitivity using a behavioral indicator of pain but not on a perceptual indicator. What explains these findings? Picking behavior over time may have desensitized the SPD group to painful stimuli in terms of autonomic responses, but not the subjective sense of levels of pain. Picking may act as a way of calming a person, reducing heart rate, and thereby over time result in feeling less pain. This in turn produces the cycle of reinforcing picking behavior as a sort of self-soothing mechanism.

Alternatively, a preexisting lack of an autonomic response to pain may be one possible reason why a person develops a skin picking compulsion. Many people pick a little from time to time as part of normal grooming practices. For those who fail to develop a strong autonomic response, there may be less incentive to reduce or stop the behavior. Finally, while we did not find that people with SPD had a different subjective response to cold pressor pain in a hand, the possibility remains that repeated picking at particular body sites could lead to localized changes in pain perception, such that picking becomes less painful over time, and therefore more prone to repetition due to lack of punishment in operant conditioning terms.

One final interpretation of these findings is that individuals with SPD actually have an aberrant stress response, instead of being characterized by altered autonomic reactions to pain. The cold pressor task has been frequently used in stress research and is known to be associated with mild to moderate activation of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenocortical (HPA) axis (e.g. increase in cortisol) (Schwabe et al., 2008) and this may be correlated with increased heart rate during stress. Individuals with SPD could therefore have blunted corticol reactivity which may explain these findings as well.

Pain has been examined in other psychiatric disorders and so these findings add to our understanding of cross-diagnostic elements in mental health. A study of patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) who engaged in non-suicidal self-injury found that these individuals report diminished pain perception (Franklin et al., 2012). In our study, SPD participants reported pain perception on par with the healthy controls. This finding may suggest that individuals with SPD are distinct from those who self-injure even though both picking and self-injury may serve, in part, an emotion regulation function (Schmahl and Baumgärtner, 2015; Snorrason et al., 2010; Roberts et al., 2013).

The dampened autonomic response to pain, shown in the current study for SPD, may offer insights into possible future interventions for this neglected psychiatric condition. If the autonomic response was heightened or ‘normalized’, could the pain worsen and thereby be used to de-incentivize people from picking? Could medications that increase heart rate, such as stimulants, or even caffeine, be used safely to produce an unpleasant autonomic response to picking? This may be a potentially useful area for future study particularly given that there is no first-line medication treatment for SPD and that pharmacotherapy trials of more traditional medications have resulted generally in lackluster outcomes at best (Schumer et al., 2016).

This study has several limitations. First, because a small sample was used, it is unclear how generalizable our results are to the larger population of individuals with SPD. Second, we used a well-respected model of pain perception (the cold pressor test), but other methods of assessing response to painful stimuli could theoretically yield different results. Third, statistical power might have been limited to detect more subtle differences such as lack of significant effect of disease severity on cold pressor test measures. Finally, the study sample was too small to examine differences between male and female SPD participants. This would be potentially important given that studies have showed that men and women differ significantly with regard to pain perception, especially in experimental conditions (Racine et al., 2012). Despite these limitations, the study inclusion criteria were fairly broad and the study used both objective measures of heart rate and blood pressure.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, these results suggest that adults with SPD may have decreased autonomic response to pain, as indexed by heart rate response. Future research should be directed at understanding the mechanisms of pain regulation in SPD, and whether these mechanisms can be targeted with novel interventions with a view to helping patients reduce the frequency of skin picking.

Highlights.

Little is known as to whether individuals with skin picking disorder have different pain thresholds or pain tolerances.

Skin picking disorder was associated with significant dampened autonomic response to cold pressor pain.

Skin picking disorder was not associated with differences in pain tolerance, recovery time, or blood pressure.

References

- Al’ Absi M, Wittmers LE, Ellestad D, et al. Sex differences in pain and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical responses to opioid blockade. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:198–206. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000116250.81254.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LM, Mutasim DF, Dwight MM. An open clinical trial of fluvoxamine treatment of psychogenic excoriation. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19:15–18. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199902000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) Vol. 1629 American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aziato L, Dedey F, Marfo K, Asamani JA, Clegg-Lamptey JN. Validation of three pain scales among adult postoperative patients in Ghana. BMC Nurs. 2015;14:42. doi: 10.1186/s12912-015-0094-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christenson GA, Raymond NC, Faris PL, et al. Pain thresholds are not elevated in trichotillomania. Biol Psychiatry. 1994;36:347–349. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)90634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diefenbach GJ, Tolin DF, Meunier S, Worhunsky P. Emotion regulation and trichotillomania: a comparison of clinical and nonclinical hair pulling. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2008;39:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerden EG, Albanese M-C. Localization of pain-related brain activation: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging data. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34:109–149. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens JL, Gil KM. Experimental induction of pain: Utility in the study of clinical pain. Behav Ther. 1995;26:197–216. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. American Psychiatric Press; 1997. p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Flessner CA, Woods DW. Phenomenological characteristics, social problems, and the economic impact associated with chronic skin picking. Behav Modif. 2006;30(6):944–963. doi: 10.1177/0145445506294083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Aaron RV, Arthur MS, Shorkey SP, Prinstein MJ. Nonsuicidal self-injury and diminished pain perception: the role of emotion dysregulation. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(6):691–700. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE. Impulse control disorders: a clinician's guide to understanding and treating behavioral addictions. WW Norton & Company; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Chamberlain SR, Keuthen NJ, Lochner C, Stein DJ. Skin picking disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(11):1143–1149. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12040508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Lamotrigine treatment of pathologic skin picking: an open-label study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1384–1391. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Stein DJ. Body-focused repetitive behavior disorders in ICD-11. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2014;36(Suppl 1):59–64. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SL, Storch EA, Berlanga L. Skin picking behaviors: An examination of the prevalence and severity in a community sample. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(3):314–319. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keuthen NJ, Koran LM, Aboujaoude E, Large MD, Serpe RT. The prevalence of pathologic skin picking in US adults. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(2):183–186. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odlaug BL, Grant JE. Clinical characteristics and medical complications of pathologic skin picking. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(1):61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odlaug BL, Hampshire A, Chamberlain SR, Grant JE. Abnormal brain activation in excoriation (skin-picking) disorder: evidence from an executive planning fMRI study. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(2):168–174. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.155192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine M, Tousignant-Laflamme Y, Kloda LA, Dion D, Dupuis GI, Choinière M. A systematic literature review of 10 years of research on sex/gender and experimental pain perception - Part 1: Are there really differences between women and men? Pain. 2012;153(3):602–618. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S, O’Connor K, Bélanger C. Emotion regulation and other psychological models for body-focused repetitive behaviors. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:745–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahl C, Baumgärtner U. Pain in Borderline Personality Disorder. Mod Trends Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;30:166–175. doi: 10.1159/000435940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumer MC, Bartley CA, Bloch MH. Systematic review of pharmacological and behavioral treatments for skin picking disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(2):147–152. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe L, Haddad L, Schachinger H. HPA axis activation by a socially evaluated cold-pressor test. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:890–895. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snorrason I, Smári J, Olafsson RP. Emotion regulation in pathological skin picking: findings from a non-treatment seeking sample. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2010;41(3):238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker BT, Woods DW, Flessner CA, Franklin SA, Franklin ME. The Skin Picking Impact Project: phenomenology, interference, and treatment utilization of pathological skin picking in a population-based sample. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(1):88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winchester WJ, Gore K, Glatt S, et al. Inhibition of TRPM8 channels reduces pain in the cold pressor test in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;351:259–269. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.216010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong DL, Baker CM. Pain in children: comparison of assessment scales. Pediatr Nurs. 1988;14:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]