Abstract

In this article, the authors posit that programs promoting nurturing parent–child relationships influence outcomes of parents and young children living in poverty through two primary mechanisms: (a) strengthening parents’ social support and (b) increasing positive parent–child interactions. The authors discuss evidence for these mechanisms as catalysts for change and provide examples from selected parenting programs that support the influence of nurturing relationships on child and parenting outcomes. The article focuses on prevention programs targeted at children and families living in poverty and closes with a discussion of the potential for widespread implementation and scalability for public health impact.

A nurturing caregiving relationship is vital for all children, particularly within the first years of life. Such relationships may be especially important for children living in poverty, who are at heightened risk for poor health outcomes and delays in social, emotional, and cognitive development (Bitsko et al., 2016). Large-scale epidemiological studies, such as the Adverse Childhood Experiences study (Anda et al., 2006), and neurobiological research support the premise that early trauma and family stress have damaging consequences on development via physiological adaptations that impair neurological, metabolic, and immunologic systems (Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011). Fortunately, neurobiological and developmental research also indicates the mitigating effect of nurturing and stable relationships on the negative outcomes of early adversity (e.g., Luby et al., 2013).

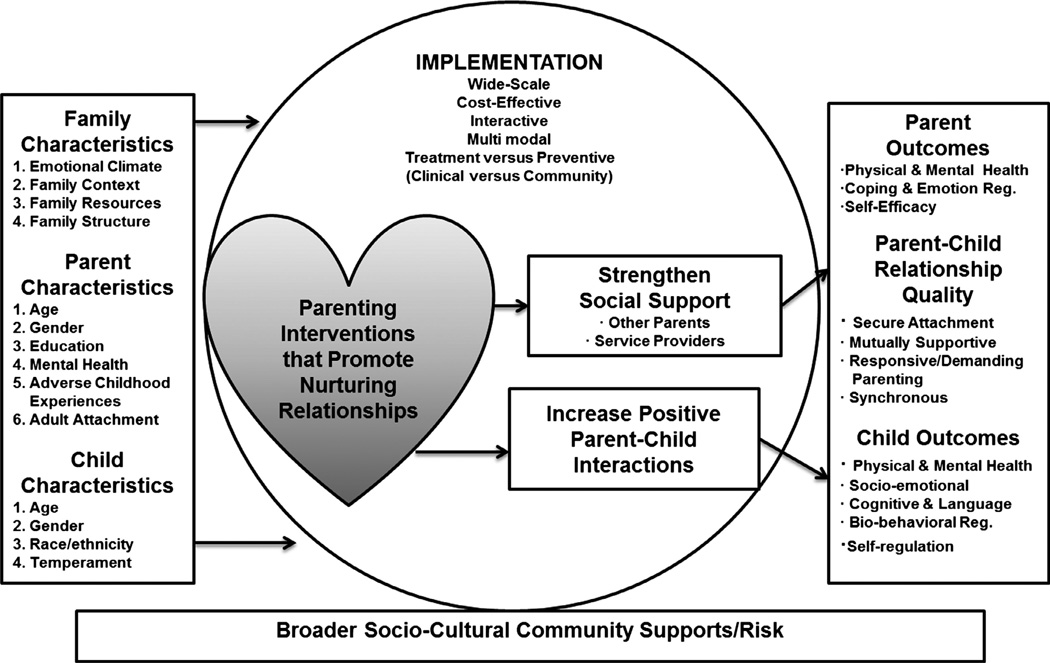

We argue that the impact of poverty on child development is a critical public health issue calling for early, scalable prevention and intervention efforts to impact the nearly 16 million children living below the poverty line in the United States (Jiang, Ekono, & Skinner, 2015) and 1 billion worldwide (Gordon, Nandy, Pantazis, Pemberton, & Townsend, 2003). Programs that support parents as frontline public health workers in the trenches of children’s health and development have significant potential as a preventive strategy to address long-term effects associated with poverty (Yoshikawa, Aber, & Beardslee, 2012). We propose that prevention programs promoting nurturing and stable relationships counteract many of the negative effects of early adversity and intergenerational poverty. Our model, the Building Early Relationships Model of Change (see Figure 1), is set in the broader sociocultural context and acknowledges that family, parent, and child characteristics influence intervention implementation and subsequent outcomes. As outlined next, we posit that programs that promote supportive and nurturing relationships between caregivers and other adults, and between caregivers and children, influence both parents’ and children’s outcomes (e.g., physical and mental health) through two primary mechanisms: (a) strengthening parents’ social support and (b) increasing positive parent–child interactions. Below, we discuss evidence for these mechanisms and provide examples of programs that support nurturing relationships (Legacy for Children™, Triple P—Positive Parenting Program, Family Check-Up, and Nurse–Family Partnership [NFP]).

Figure 1.

Building early relationships model of change.

Mechanisms of Influence

Strengthening Parents’ Social Support

Economically disadvantaged families experience environments characterized by chaos, lack of control, and high levels of stress. One of the primary mechanistic hypotheses explaining the relationship between low SES, chronic stress, and poor health focuses on the role of inflammation (Miller et al., 2011). Research in children and adults has established an association between low SES and elevated levels of inflammatory markers (e.g., interleukin-6, C-reactive protein) as well as inflammation-related diseases such as asthma. Animal models also provide evidence that stressful early-life experiences have far-reaching consequences via neurological, metabolic, and epigenetic as well as immunologic effects (McEwen, 2008). Supportive and warm maternal care has been found to buffer these effects in both animals and humans (Chen, Miller, Kobor, & Cole, 2011). However, families living in low-economic households often experience less support due to an increased likelihood of social ties with high levels of stress and decreased access to resources (e.g., Balaji et al., 2007). This social isolation and lack of social capital has been associated with a number of poor health and developmental outcomes (Kawachi & Berkman, 2001). Although demonstrated inequalities in SES are associated with stress and adjustment difficulties, social support can reduce the impact of stress and directly support physical and mental health (McConnell, Breitkreuz, & Savage, 2011).

The social support literature is vast and has been operationalized in many ways. Social support is frequently conceptualized as having three primary components: sources of support (e.g., family, friends, partners, colleagues), types of support (i.e., emotional, appraisal, information, and instrumental), and the perceived quantity and/or quality of support (Berkman & Glass, 2000). Social support can be further defined by both its functional and structural components. The functional components of social support are the emotional (e.g., comfort, positive reinforcement, empathy), instrumental (e.g., assistance with financial, child-care, or material needs), or informational assistance (e.g., personal advice or life skills information) that others provide to an individual (Letourneau, Stewart, & Barnfather, 2004). Social networks are the structural component of social support, which include the number and type of social ties or connections with individuals and community (Letourneau et al., 2004). The economic and collective value of these social networks (e.g., having someone you can trust or rely on) has been defined as social capital (Kawachi & Berkman, 2001). These elements of social support can be uniquely important in reducing stress and promoting parent and child outcomes for low-SES families; therefore, we will briefly review these elements as they relate to the proposed model. Although types of support are described separately below for clarity, it is important to note different types are often interrelated and can create synergistic effects on parenting and child outcomes when combined.

Research indicates that among low-income families, social support is associated with parents’ mental and physical health, coping and emotion regulation, and self-efficacy (e.g., Lee, Halpern, Hertz-Picciotto, Martin, & Suchindran, 2006). Larger social networks and more emotional support from those networks have been linked to higher maternal–child responsiveness and better cognitive stimulation among low-income families (e.g., Burchinal, Follmer, & Bryant, 1996). Perceived social support (emotional, instrumental, informational, and social capital) is also associated with positive parenting behaviors and reduced child behavior problems, and can buffer the impact of stress due to financial hardship on negative parent–child interactions (McConnell et al., 2011). National survey data indicate that social support not only impacts parental well-being but can also exert a buffering effect on the relationship between maternal depression and child behavior problems (Lee et al., 2006).

Prevention models for at-risk familes have posited the importance of family support programs and parental social relationships for the prevention of long-term child behavioral problems (Yoshikawa, 1994) and for fostering resilience among maternal primary caregivers (Luthar, 2015). For example, a review of social support interventions that aim to improve health and psychosocial outcomes found that 83 of the 100 social support programs reviewed were more effective than no treatment or active controls and that social support skills training may be particularly beneficial (Hogan, Linden, & Najarian, 2002). In individual interventions, social support can be provided by the interventionist, who can also help build social networks and model nurturing relationships. The working alliance, or the therapeutic connection between interventionist and client, has been associated with positive intervention outcomes (Martin, Garske, & Davis, 2000) and has more recently been used to measure the quality of the relationships between members in an intervention group.

Many parenting programs are conducted in a group format or contain group components (e.g., some levels of Triple P—Positive Parenting Program, Triple P; Legacy for Children™, Legacy), which allow parents to support one another. Once established, the support and social network among parents in a group can last beyond the intervention (Scott, Brady, & Glynn, 2001). Programs may directly provide informational, emotional, and instrumental support (e.g., Family Check-Up); model-positive social relationships with adult peers and between parents and children (e.g., NFP); or expand the social networks and social capital of families (e.g., Legacy). Group-based programs are an opportunity for parents to explore parenting topics (informational and instrumental support), share parenting challenges and successes within a supportive, safe community of their peers (emotional support), and discuss strategies for reducing stress and promoting parental health. For some group programs, a specific goal is to develop social support and a sense of community (Scott et al., 2001). For example, the Legacy program contains session components designed to support maternal autonomy, self-efficacy, and the development of leadership skills so the mother can become an active community member (building social capital). Legacy group sessions also provide social models of positive, consistent relationships for mothers and their children. The types of support derived from a group parenting program have been documented to improve short- and medium-term parental stress and confidence (Barlow, Smailagic, Huband, Roloff, & Bennett, 2014), which in turn can influence the parent–child relationship. Social support is typically assessed via standardized self-report measures, and often types and sources of support are examined (McConnell et al., 2011).

Increasing Positive Parent–Child Interactions

The development of adaptive biobehavioral responses to stress is dependent on the presence of nurturing relationships in infancy and early childhood. Interventions that strengthen these relationships have the potential to yield long-term gains in social and emotional development, particularly in children at risk because of poverty and toxic stress. Infants and young children depend on caregivers for survival, and meeting both physical and emotional needs are essential for healthy development. Healthy and nurturing parent–child interactions guide children’s emotional and cognitive development and allow children to explore their world with a sense of emotional security. Securely attached children are typically well-adjusted, whereas children who experience insecure attachments are at higher risk for developmental disorders and psychopathology (Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson, & Collins, 2005).

A key factor in attachment is parental sensitivity and responsiveness, that is, how sensitive parents are to children’s signals and how well they respond to children’s physical and emotional needs. Numerous studies show that children with sensitive and nurturing caregivers in early childhood exhibit fewer behavioral and mental health problems, and are more likely to be prosocial and succeed in school (National Research Council & Institute of Medicine, 2009). Results from randomized control trials indicate that interventions that help parents become more synchronous and nurturing, and avoid frightening behaviors, result in lower rates of disorganized attachment and more adaptive biobehavioral responses to stress in at-risk children (e.g., Bernard, Dozier, Bick, & Gordon, 2015).

Indeed, increasing positive interactions among parents and children is a cornerstone of many parenting interventions (e.g., Legacy, Triple P), and studies support the importance of daily, positive parent–child exchanges that occur through play, reading, conversations, and shared activities. Play can be an important component of the parent–child relationship, and improving the quality of interaction during play between a parent and child can significantly impact the quality of that relationship. Mothers who engage in attentive and sensitive play with their young children are sharing joint attention and positive affect while also promoting language. Over time, quality play has the potential to improve children’s language and cognitive development (Weisberg, Zosh, Hirsh-Pasek, & Golinkoff, 2013).

Research also indicates that encouraging parents to effectively praise their children and show delight and joy in their daily interactions results in more nurturing behaviors and increased security of attachment. Moreover, parents can learn to reinterpret their children’s behavior and cues in a less negative way, and to see dysregulation as a bid for help rather than a rejection of the parent. This reinterpretation of behavior can lead to more support and nurturance (see Bernard et al., 2015).

In addition to nurturance, children need stability, consistency, clear limits, and guidance. Such environments help children feel safe and secure because they know what is expected, and their worlds are predictable and less emotionally chaotic (see Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers, & Robinson, 2007). Children also need a sense of agency and some control over their environment. This can be accomplished by following a child’s lead during play, providing choices and encouraging autonomy, and establishing routines and rituals in the home. Many parenting programs directly address the importance of consistency and limit setting (e.g., Triple P). This can be implemented through behavioral modification charts (e.g., Triple P, Family Check-Up) or through discussions regarding the importance of routines (e.g., Legacy, NFP).

Assessing parent–child interactions with young children is typically done through observational techniques, which can be time-consuming and expensive. However, parent self-report measures are an option, as are brief observational assessments that can be easily coded (e.g., PICCOLO, Parenting Interactions with Children: Checklist of Observations Linked to Outcomes; Roggman, Cook, Innocenti, Norman, & Christiansen, 2013).

It should be noted that some parenting programs focus solely on maternal caregivers (e.g., Legacy), and fathers are often underrepresented in program outcome data (see Table 1). However, we believe that our model is relevant for fathers as well as other primary caregivers, and have noted in Table 1 whether programs were tested with mothers and/ or fathers. Increasingly, parenting programs are specifically targeting fathers (see Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2007 for a review), and implementation and effectiveness studies of fathering programs are greatly needed.

Table 1.

Representative Early Childhood Prevention-Focused Parenting Interventions to Promote Child Health and Development Through the Parent–Child Relationship and Social Support

| Intervention | Delivery (home visit, HV, group) |

Targeted caregivers in studies represented below |

Selected child and family outcomes | Duration of effects postprogram |

Cost information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Family Check-Up: Brief program designed to improve family management, followed up with tailored suggestions for family- based interventions |

HV | Mothers and fathers; studies predominantly measure mother–child outcomes (selected studies sampled mothers only) |

Significant maternal and child effects compared to controls |

Significant effects up to 5½ years | $200–265 per family for 1 year (serving 150–200 families) |

|

Legacy for Children™ (Legacy): Group-based, public health approach to promote child health and development through positive parenting |

Group, HV component |

Mothers | Significant site specific child outcomes related to comparison groupc

|

Significant effects up to 2 years |

Costs avoided:$178,000 per child at high risk for severe behavioural problems, $91,100 per child at high risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

|

Nurse–Family Partnership: Nurses support first-time mothers to improve pregnancy outcomes, become knowledgeable and responsible parents, and improve children’s health and development |

HV | Mothers | Long-lasting, significant effects for highest risk populations (i.e., low psychological resource, low-income mothers) related to comparison groups

|

Significant effects up to 18 years |

Cost–benefit: $2.37 for every dollar spent on implementationk;$5,074 per family for 1 year (serving 200 families) |

|

Triple P—Positive Parenting Program: Multilevel program designed to reduce risk of trauma and behavioral/ emotional issues by supporting parental competence and preventing dysfunctional parenting practices; Levels 1–3 can be considered primary and secondary prevention |

Group, HV | Mothers and fathers; selected studies predominantly sampled mothers (e.g., 79.1% mothersi) |

Significant effects compared to controls

|

Significant effects up to 3 years |

Cost–benefit: $6.06 for every dollar spent on implementationk;$23.67 per family (inclusive of all levels in community serving 100,000 families) |

Sample Interventions

We have chosen four representative early childhood (prenatal to age 5) primary and secondary prevention programs that can be universally applied to families at risk due to poverty. We focus on a select number of programs due to space limitations. We chose to highlight interventions that target increasing positive parent–child interactions and reflect the importance of social support through group intervention (e.g., Legacy, Triple P), supportive program interventionists (Family Check-Up, NFP), or specific curricula focused on increasing social support and connections (Legacy). Cohen’s effect sizes (d) or odds ratios (OR) are used to describe the data whenever possible. Effect sizes can be interpreted as small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), and large (d ≥ 0.8). ORs less than 1 indicate the exposure is associated with a lower odds of the outcome; ORs greater than 1 describe a higher odds of the outcome. For example, an OR of 2 would mean that odds of the outcome happening was twice as likely in the intervention versus the comparison group. See Table 1 for a summary of program information and comparison across programs.

Family Check-Up is a brief home visiting program that uses aspects of parent management training and motivational interviewing to help at-risk parents become more positive and effective in their parenting. The program includes assessment and discussion of parental strengths and areas for change over three sessions, as well as followup with tailored suggestions for family-based interventions as needed. Review of selected caregiver outcomes reveal significant effects compared to controls in improved observed positive behavior support (nonaversive, reinforcing adult–child interactions; d = 0.33; Dishion et al., 2008) and decreases in depressive symptoms (d = 0.18; Shaw, Connell, Dishion, Wilson, & Gardner, 2009). This program also demonstrates effects in child outcomes, with greater reductions in externalizing (d = 0.23) and internalizing (d = 0.21) problems in children aged 2–4 compared to controls (Shaw et al., 2009). Additionally, this intervention has been found to be as effective for families facing extreme poverty and social risks as it is for families with less severe risks (Dishion et al., 2008). Program materials are available in Spanish, and the program is being used in English and Spanish by over 300 providers globally (Arizona State University REACH Institute, n.d.). The program has an extensive body of research evidence and costs an estimated $200–265 to serve one family for 1 year across 150–200 total families.

Legacy for Children™ is a group-based, public health approach to improve child health and development through positive parenting among low-income mothers. Legacy was designed to impact child development through three mechanisms: promoting sensitive, responsive mother–child interactions; promoting maternal sense of community (i.e., social support); and enhancing maternal self-efficacy. Trained group leaders and supervisors facilitate weekly sessions within early childhood agencies and pediatric primary care sites. Evaluation of Legacy indicates significant child outcomes compared to the comparison group, with fewer behavioral concerns at 24 months (d = −0.37) and socioemotional problems at 48 months (d = −0.51), as well as lower risk for behavior problems from 24 to 60 months of age. Findings also reveal lower risk for hyperactive behavior at 60 months (d = −0.38) for children of mothers who participated in Legacy (Kaminski et al., 2013). Community-based implementations and adaptations of Legacy are currently underway in child-care and healthcare settings, and a Spanish language adaptation of Legacy is also in progress. Data on the cost per family are not published for Legacy; however, the incremental cost for Legacy was $178,000 avoided per child at high risk for severe behavioral problems and $91,100 avoided per child at high risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder without Legacy (Corso, Visser, Ingels, & Perou, 2015).

NFP is a home visiting program in which nurses support first-time mothers to improve pregnancy outcomes, become knowledgeable and responsible parents, and improve their children’s health and development. It was developed to improve maternal and child health outcomes by providing instrumental and emotional support for first-time mothers, particularly those at risk due to poverty (Olds et al., 2014). The widely disseminated program has demonstrated long-lasting, significant effects for highest risk populations (i.e., low psychological resource, low-income mothers). Examples of demonstrated maternal outcomes include reduced all-cause maternal mortality (Olds et al., 2014) and increased maternal relationship stability (d = 0.24; Olds et al., 2004). Child outcomes of NFP include decreased preventable-cause mortality in firstborn children (Olds et al., 2014), fewer internalizing problems (OR = 0.63), improved academic achievement (d = 0.18; Kitzman et al., 2010), higher intellectual functioning and receptive vocabulary (d = 0.17–0.25), and fewer behavior problems (OR = 0.32; Olds et al., 2004). However, some impacts for NFP vary based on who is delivering the intervention, the gender of the child, and the outcome of interest (Kahn & Moore, 2010). NFP is implemented internationally, and costs an estimated $5,074 to serve one family for 1 year across 200 total families. It yields an estimated $2.37 in benefit for every dollar spent on implementation (Lee et al., 2012).

Triple P—Positive Parenting Program, Triple P, is a multilevel program designed to reduce risk of trauma and behavioral/emotional issues by supporting parental competence and preventing dysfunctional parenting practices. Levels 1 through 3 can be considered primary and secondary prevention; whereas Levels 4 and 5 are tertiary prevention or treatment for behavior problems. Level 1 is universal Triple P, focused on public health communication strategies; Level 2 consists of seminars and brief consultation on positive parenting; and Level 3 is individual or group counseling for mild and moderate behavior difficulties. Level 4 consists of counseling for parents with severe behavior problems, and Level 5 is further targeted counseling for the highest risk families (e.g., parental mental health concerns or maltreatment; Nowak & Heinrichs, 2008). Although effect sizes are largest for the increased intensity intervention in Levels 4 and 5, there are significant effects for prevention levels compared to controls. Significant differences in caregiver outcomes include improved well-being (d = 0.19) and parenting skills (d = 0.38; Nowak & Heinrichs, 2008), as well as less stress, depression, and use of coercive parenting (Sanders et al., 2008). Reduced rates of child abuse (d = 1.09) and foster care placements (d = 1.22) were also found for concurrent delivery of all levels (Prinz, Sanders, Shapiro, Whitaker, & Lutzker, 2009). Significant effects in child outcomes include reductions in problem behavior (d = 0.21; Nowak & Heinrichs, 2008) and fewer behavioral and emotional problems (concurrent delivery; Sanders et al., 2008). Triple P is offered in different delivery modes (e.g., group-based) and intensities, and with adaptations and enhancements for specific populations (e.g., grandparents), and has been translated into 19 languages. Triple P costs an estimated $23.67 to serve one family for 1 year across a community of 100,000 total families (inclusive of all levels) and yields an estimated $6.06 in benefit for every dollar spent on implementation (Lee et al., 2012).

Conclusions, Next Steps, and Opportunities

Early exposure to the stresses associated with poverty and family dysfunction jeopardizes physical, cognitive, and social development. Our Building Early Relationships Model proposes several mechanisms that mitigate these risks and promote resilience. Sensitive, responsive caregiving and relationships that support mothers, fathers, and other caregivers can have a significant and positive impact on the development of at-risk children that is evident years after the completion of the intervention (e.g., Kaminski et al., 2013; Olds et al., 2004). However, the scale-up of evidence-based programs is not an easy task and poverty is a complex problem; early childhood interventions have experienced differential impacts during dissemination phases in part due to inconsistencies in implementation quality (e.g., fidelity, intensity; Sweet & Appelbaum, 2004). The duration of impacts for the selected programs reviewed here varies from 2 to 20 years postprogram. Interventions need to demonstrate not only initial effectiveness but also evidence for community-based replicability and adaptations (Sandler, Ingram, Wolchik, Tein, & Winslow, 2015). For greatest impact, dissemination and scale-up phases require attention to factors such as program packaging and accessibility, training and cost, technical support and quality assurance monitoring, and strong community partnerships (e.g., Head Start centers, pediatric clinics) that build implementation capacity (Frieden, 2013). Capacity building would require substantial collaboration across public health, pediatric, and other agencies responsible for providing services to children but could yield widespread impact on early childhood and lifelong health.

Taking a public health perspective allows for a focus on prevention instead of intervention, addressing the risk factors associated with poverty before they lead to disorders. If targeted appropriately and delivered with fidelity, high-quality prevention for families at risk for poor developmental and health outcomes due to poverty can be cost effective and effects can last into adulthood (Heckman, 2006). Combined with other evidence-based educational strategies, these programs have the potential for even further impacts (Yoshikawa, 1994). In summary, increasing the availability of programs that strengthen parents’ social support, and increase positive parent–child interactions through the varied settings that low-income parents already access (e.g., healthcare offices, community and faith-based organizations, schools, and homes), has the potential to have a significant impact on children’s health and developmental outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Work on this article was supported in part by a grant to Amanda Sheffield Morris and Jennifer Hays-Grudo from the George Kaiser Family Foundation. This research was supported in part by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and CDC. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributor Information

Amanda Sheffield Morris, Oklahoma State University.

Lara R. Robinson, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Jennifer Hays-Grudo, Oklahoma State University.

Angelika H. Claussen, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Sophie A. Hartwig, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Amy E. Treat, Oklahoma State University

References

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Walker J, Whitfield CL, Bremner JD, Perry BD, Giles WH. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2006;56:174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arizona State University REACH Institute. Family Check-Up for providers. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://reachin stitute.asu.edu/family-check-up/agencies. [Google Scholar]

- Balaji AB, Claussen AH, Smith DC, Visser SN, Morales MJ, Perou R. Social support networks and maternal mental health and well-being. Journal of Women’s Health. 2007;16:1386–1396. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.CDC10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow J, Smailagic N, Huband N, Roloff V, Bennett C. Group-based parent training programmes for improving parental psychosocial health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;5:300–332. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002020.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T. Integration, social networks, social support, and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 137–173. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Dozier M, Bick J, Gordon MK. Intervening to enhance cortisol regulation among children at risk for neglect: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Development and Psychopathology. 2015;27:829–841. doi: 10.1017/S095457941400073X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsko RH, Holbrook JR, Robinson LR, Kaminski JW, Ghandour R, Smith CD, Peacock G. Health care, family, and community factors associated with mental, behavioral, and developmental disorders in early childhood—United States, 2011-2012. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;65:221–226. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6509a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J, Carrano BS, Allen T, Bowie L, Mbawa K, Matthews G. Elements of promising practice for fatherhood programs: Evidence-based findings on programs for fathers. Washington DC: National Responsible Fatherhood Clearinghouse; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Follmer A, Bryant DM. The relations of maternal social support and family structure with maternal responsiveness and child outcomes among African American families. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:1073–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Miller GE, Kobor MS, Cole SW. Maternal warmth buffers the effects of low early-life socioeconomic status on pro-inflammatory signaling in adulthood. Molecular Psychiatry. 2011;16:729–737. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corso PS, Visser SN, Ingels JB, Perou R. Cost-effectiveness of Legacy for Children™ for reducing behavioral problems and risk for ADHD among children living in poverty. Journal of Child and Adolescent Behavior. 2015;3 doi: 10.4172/2375-4494.1000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson MN. The Family Check-Up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development. 2008;79:1395–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden TR. Six components necessary for effective public health program implementation. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;104:17–22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D, Nandy S, Pantazis C, Pemberton S, Townsend P. Child poverty in the developing world. Bristol, UK: The University of Bristol and The Policy Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ. Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science. 2006;312(5782):1900–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.1128898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan BE, Linden W, Najarian B. Social support interventions: Do they work? Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:381–440. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Ekono MM, Skinner C. Basic facts about low-income children: Children under 18 years, 2013. New York, NY: National Center for Children in Poverty; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn J, Moore KA. Child trends. #2010 200008. Washington, DC: Child Trends; 2010. What works for home visiting programs: Lessons from experimental evaluations of programs and interventions; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski JW, Perou R, Visser S, Scott K, Beckwith L, Howard J, Danielson M. Behavioral and socioemotional outcomes through age 5 of the Legacy for ChildrenTM public health approach to improving developmental outcomes among children born into poverty. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:1058–1066. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78:458–467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzman HJ, Olds DL, Cole RE, Hanks CA, Anson EA, Arcoleo KJ, Holmberg JR. Enduring effects of prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses on children: Follow-up of a randomized trial among children at age 12 years. JAMA Pediatrics. 2010;164:412–418. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Aos S, Drake E, Pennucci A, Miller M, Anderson L. Return on investment: evidence-based options to improve statewide outcomes, April 2012 update. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lee L-C, Halpern CT, Hertz-Picciotto I, Martin SL, Suchindran CM. Child care and social support modify the association between maternal depressive symptoms and early childhood behaviour problems: A US national study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006;60:305–310. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.040956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau NL, Stewart MJ, Barnfather AK. Adolescent mothers: Support needs, resources, and support- education interventions. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:509–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby J, Belden A, Botteron K, Marrus N, Harms MP, Babb C, Barch D. The effects of poverty on childhood brain development: The mediating effect of caregiving and stressful life events. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167:1135–1142. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS. Mothering mothers. Research in Human Development. 2015;12:295–303. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2015.1068045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DJ, Garske JP, Davis MK. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell D, Breitkreuz R, Savage A. From financial hardship to child difficulties: Main and moderating effects of perceived social support. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2011;37:679–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. Understanding the potency of stressful early life experiences on brain and body function. Metabolism Clinical and Experimental. 2008;57:S11–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137:959–997. doi: 10.1037/a0024768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development. 2007;16:362–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council & Institute of Medicine. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak C, Heinrichs N. A comprehensive meta-analysis of Triple P–positive parenting program using hierarchical linear modeling: Effectiveness and moderating variables. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2008;11:114–144. doi: 10.1007/s10567-008-0033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Kitzman H, Cole R, Robinson J, Sidora K, Luckey DW, Holmberg J. Effects of nurse home-visiting on maternal life course and child development: Age 6 follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1550–1559. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Kitzman H, Knudtson MD, Anson E, Smith JA, Cole R. Effect of home visiting by nurses on maternal and child mortality: Results of a two-decade follow-up of a randomized, clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014;168:800–806. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz RJ, Sanders MR, Shapiro CJ, Whitaker DJ, Lutzker JR. Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. Triple P system population trial. Prevention Science. 2009;10:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0123-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roggman LA, Cook GA, Innocenti MS, Norman VJ, Christiansen K. Parenting interactions with children. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MR, Ralph A, Sofronoff K, Gardiner P, Thompson R, Dwyer S, Bidwell K. Every family: A population approach to reducing behavioral and emotional problems in children making the transition to school. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2008;29:197–222. doi: 10.1007/s10935-008-0139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I, Ingram A, Wolchik S, Tein J-Y, Winslow E. Long-term effects of parenting-focused preventive interventions to promote resilience of children and adolescents. Child Development Perspectives. 2015;9(3):164–171. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D, Brady S, Glynn P. New mother groups as a social network intervention: Consumer and maternal and child health nurse perspectives. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;18:23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Connell A, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, Gardner F. Improvements in maternal depression as a mediator of intervention effects on early childhood problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:417–439. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson EA, Collins WA. The development of the person: The Minnesota study of risk and adaptation from birth to adulthood. New York, NY: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet MA, Appelbaum MI. Is home visiting an effective strategy? A meta-analytic review of home visiting programs for families with young children. Child Development. 2004;75:1435–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg DS, Zosh JM, Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff RM. Talking it up: Play, language development, and the role of adult support. American Journal of Play. 2013;6:39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H. Prevention as cumulative protection: Effects of early family support and education on chronic delinquency and its risks. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:28–54. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Aber JL, Beardslee WR. The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: Implications for prevention. American Psychologist. 2012;67:272. doi: 10.1037/a0028015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]