Abstract

The Extreme Microbiome Project (XMP) is a project launched by the Association of Biomolecular Resource Facilities Metagenomics Research Group (ABRF MGRG) that focuses on whole genome shotgun sequencing of extreme and unique environments using a wide variety of biomolecular techniques. The goals are multifaceted, including development and refinement of new techniques for the following: 1) the detection and characterization of novel microbes, 2) the evaluation of nucleic acid techniques for extremophilic samples, and 3) the identification and implementation of the appropriate bioinformatics pipelines. Here, we highlight the different ongoing projects that we have been working on, as well as details on the various methods we use to characterize the microbiome and metagenome of these complex samples. In particular, we present data of a novel multienzyme extraction protocol that we developed, called Polyzyme or MetaPolyZyme. Presently, the XMP is characterizing sample sites around the world with the intent of discovering new species, genes, and gene clusters. Once a project site is complete, the resulting data will be publically available. Sites include Lake Hillier in Western Australia, the “Door to Hell” crater in Turkmenistan, deep ocean brine lakes of the Gulf of Mexico, deep ocean sediments from Greenland, permafrost tunnels in Alaska, ancient microbial biofilms from Antarctica, Blue Lagoon Iceland, Ethiopian toxic hot springs, and the acidic hypersaline ponds in Western Australia.

Keywords: metagenomics, whole genome, shotgun sequencing, extremophile, Polyzyme

INTRODUCTION

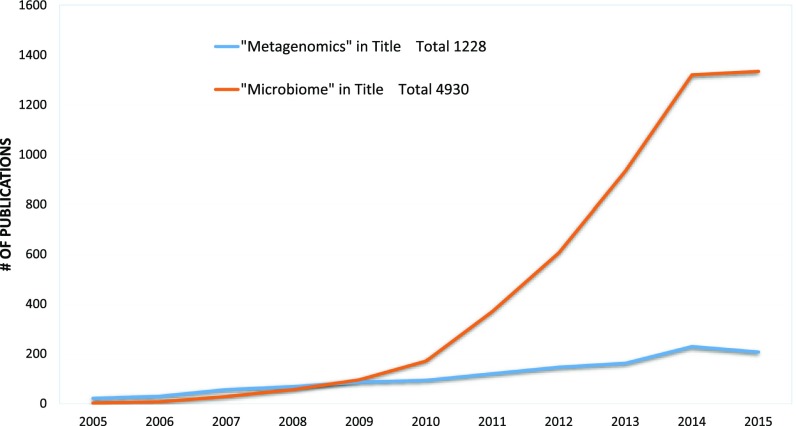

Revolutionary advances in sequencing technology have enabled extensive surveys of microbiomes and have subsequently transformed our understanding of the human-microbe interface. In the last decade, we have entered into the “microbiome era,” marked by a rapid increase of studies exploring the microbial communities that live in us, on us, and all around us (Fig. 1).1–5 Despite these major technological advances and groundbreaking studies that have been undertaken in the past few years, there are few concerted efforts dedicated to investigating the most elusive of ecological niches: the extremophiles. Physiologic, chemical, and biologic adaptations allow extremophiles to thrive in the most acidic, saline, hot, cold, and barophilic environments on our planet. The secrets to their survival lie in the versatility and adaptability of their genomes.6–8

Figure 1.

Microbiome and metagenomics publication statistics. PubMed searches for the keywords “metagenomics” and “microbiome” in the title of publications by year.

Taxonomic classification of extremophiles has been a pioneering field of study since the 1950s. Efforts to characterize extremophiles increased after the discovery of Thermus aquaticus9 and Taq polymerase,10 to such a degree that the International Society of Extremophiles was established in the 1990s and publishes the dedicated peer-reviewed journal, Extremophiles.11 In recent years, international efforts, such as the Earth Microbiome Project (EMP), have initiated large-scale endeavors to map the distribution of microorganisms (including extremophiles) across the globe. However, whereas the EMP is one of the largest contemporary microbiome projects in the world,12, 13 the methods are significantly different from those used by the XMP. This unique consortium was founded in 2014 with the intention to create a comprehensive molecular profile of various extreme sites using novel culturing methods, long-read and short-read whole genome shotgun sequencing (instead of rRNA amplicon-based methods), improved RNA and DNA extraction methods, methylation tracing, and for future studies, metaproteomics. Many of these techniques have yet to be fully developed, which is why the ABRF MGRG was established, representing a pioneering research consortium dedicated to characterizing the current methods and development of new methods for ubiquitous metagenomics and microbiomes studies.

The understanding of extremophiles—their genomes, molecular machinery, and how they interact with their environments—has potential health and research benefits for humanity. There are applications in bioremediation of polluted sites deemed too unbearable for most living organisms or as sources for novel therapeutics in medicine and potentially, an alternative process for biofuel or energy production. The metabolic mechanisms of these organisms are rather specialized and could inspire innovations in such diverse areas as synthetic biology and research into human survival in space. Many extreme environments offer relatively accessible proxies for the harsh environments found beyond Earth. This is why the consortium members are both academic and corporate, having diverse backgrounds in areas such as microbiology, genetics, oceanography, planetary science, geochemistry, and bioinformatics. Whereas most contributors are academic, several others are coming from industry including researchers from Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA), Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA), BioO Scientific (Austin, TX, USA), New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA, USA), Omega BioTek (Norcross, GA, USA), and One Codex (San Francisco, CA, USA); see www.extrememicrobiome.org for details.14

SAMPLE COLLECTION AND PROCESSING

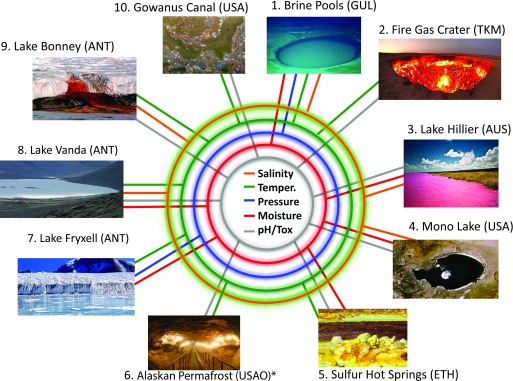

Since the inception of the XMP, the consortium has begun collecting and analyzing data from 12 sites across the world, with more sites under consideration (Fig. 2). This effort differs from other microbiome projects, as each site is sampled and analyzed as a complete stand-alone project. The selected sites are defined as extreme or “novel,” based on such metadata as salinity, temperature, pressure, moisture, pH, or remoteness, with many sites falling into more than one category. Table 1 provides details of the samples collected, including location, suspected types of organisms, and the sample-processing methods applied (e.g., culturing, DNA sequencing, and RNA sequencing).

Figure 2.

Current sites of the XMP. The XMP sites span the world with a diversity of samples that test the salinity, temperature, pressure, moisture, and pH limits of life. GUL, Gulf of Mexico; TKM, Turkmenistan; AUS, Australia; ETH, Ethiopia; and ANT, Antarctica. For the most updated list of sites, seewww.extrememicrobiome.org.

TABLE 1.

Collection sites and characteristics: phase I of the XMP

| Site name | Site type | Location | Types of organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep-sea brine lakes | Hypersaline, methyl hydrate, salt derived, and halite derived | Gulf of Mexico | Barophiles, halophiles, chemotrophs |

| Door to Hell gas crater | High and moderate temperatures, molten areas of rock and sand | Karakum Desert, Turkmenistan | Soil thermophiles, chemotrophs |

| Lake Hillier | Hypersaline, pH neutral, precipitated salt | Recherche Archipelago, Western Australia | Halophiles, methylotrophs, phototrophs, sulfobacteria |

| Greenland shelf sediments | Paleoglaciers sediment (deep-water marine sediments) | Greenland | Psychrophiles, halophiles |

| Acidic hypersaline ponds | Hyperacidic ponds | Yilgarn Craton, Australia | Acidophiles, chemotrophs |

| Mono Lake | Alkaline, hypersaline | California, USA | Halophiles, alkaphiles, methanogen, sulfate reducers |

| Permafrost | Deep frozen, high ice pressure of geologically ancient origin | Alaska, USA; Siberia, Russia | Psychrophiles, barophiles |

| Dry valley lakes | Ancient microbial biofilms | Victoria Land, Antarctica | Heterotrophs, psychrophiles, chemo/ autotrophs/sulfate reducers |

| Toxic hot springs | Volcanic hot springs acidic, alkaline, high sulfur, high chlorine, high temperature | Danakil Depression, Ethiopia | Thermophiles, acidophiles, chemotrophs, sulfate reducers |

| Great Salt Lake | Hypersaline lake | Utah, USA | Halophiles |

| Gowanus Canal | Industrial toxins, low pH, black tar sludge | New York, USA | Iron bacteria, psychrophiles, chemo/ autotrophs |

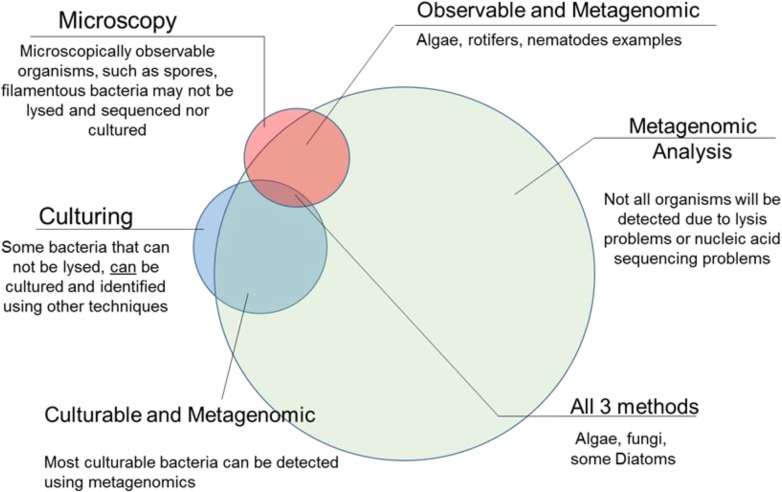

The ABRF MGRG works as a collaborative team to study these environments, using both traditional and novel methods as outlined in Fig. 3. This includes a modified, nucleic acid-free sample collection; extraction of the DNA/RNA using methods to preserve nucleic acid length; culturing; microscopy; and multiple types of nucleic acid sequencing. Culturing methods are included to address the questions of viability and codependency, as well as the relationship to the detection of species using next-generation sequencing (NGS) and bioinformatics analyses. It is well known that whereas most organisms are unculturable, there are still gaps in our knowledge about some of the culturable organisms (or ones observed by microscopy) that are not amenable to characterization by NGS technologies due to experimental limitations or challenges with nucleic acid extraction. The scenario is outlined in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Relationship among different methods of detection. Different methods of detection used in microbiology, including more traditional methods of microscopy and culturing, as well as the novel molecular approaches in metagenomics analysis. Areas of overlap between these methods are also highlighted.

Not surprisingly, there are major challenges involved with the XMP as a stand-alone, all-encompassing project, from sample collection to bioinformatics. These unique samples are often difficult to collect because of their remote site location and sometimes, even worse to extract their DNA and RNA as a result of reticent cells. Samples from harsh environments tend to have robust cell walls requiring special lysis procedures. Consequently, one of the major goals of the MGRG was development of a novel extraction method tailored to difficult samples that avoided beater beads whenever possible to minimize unnecessary shearing of DNA. These protocols included substituting a novel multienzyme blend, called “Polyzyme,” in place of lysozyme and further extraction of DNA to recover long fragment length DNA compatible with long sequencing strategies. Whereas culturing is not the primary focus of the projects, it does provide “minimum truth” in a sample and also requires multiple techniques, such as the following: 1) use of a multitude of microbial growth media and broths (including sample site enrichment media), 2) culturing of anaerobically and aerobically, 3) incubation at different times and temperatures, and 4) identification using full-length, 16S DNA sequencing and/or the Microbial Identification system (Biolog, Hayward, CA, USA).

Samples collected for the XMP are sequenced using the standard commercial sequencing platforms, including HiSeq and MiSeq (Illumina), Pacific Biosciences (Menlo Park, CA, USA), Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (Oxford, United Kingdom). A mix of these sequencing technologies allows us to not only assess the strengths and weaknesses of these different platforms but also allows us to integrate the data together to generate a comprehensive molecular profile of each sample and each site. Finally, RNA extraction is accomplished using a standard TRIzol LS procedure15 combined with a bead-beater step using Matrix A lysing matrix (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA). RNA sequencing, coupled with functional and phylogenetic bioinformatics, provides results on the dynamics of the metatranscriptome at these sites, notably, the metabolic systems of extremophiles in situ.

DEVELOPMENT OF A POLYZYME MPZ MIXTURE FOR ENHANCED DNA AND RNA EXTRACTION

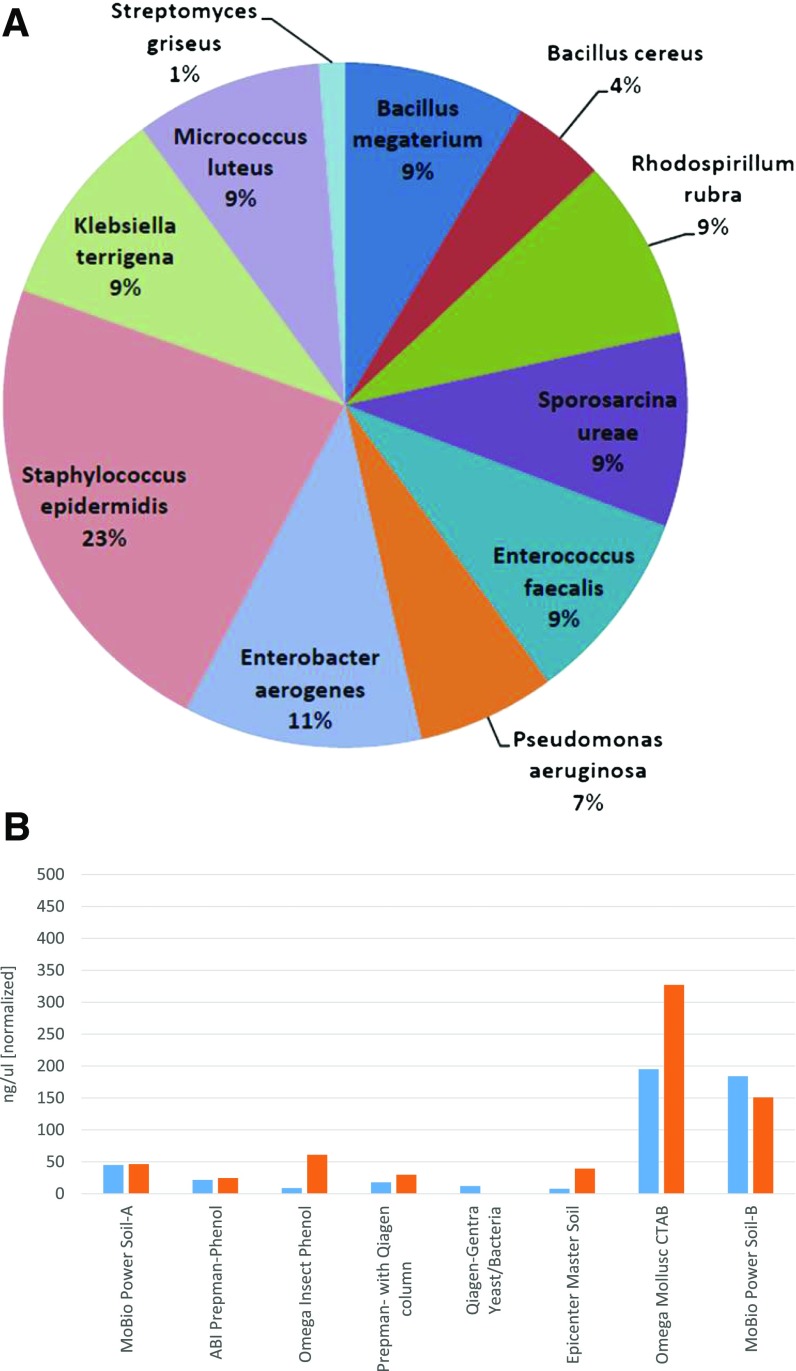

For a metagenomics study to be as comprehensive as possible, high-efficiency, high-yield, and unbiased nucleic acid extraction methods are required. Whereas it is currently possible to extract nucleic acids, it is not possible to extract 100% of all organisms, especially from different domains of life (i.e., bacteria, fungi, viruses, archaea, and other eukaryotes) or even species to species, in some cases. Moreover, the question of viability remains a challenge in the field of metagenomics, as it is not possible to determine whether the nucleic acids recovered belong to living organisms. These challenges create major obstacles for the applications of metagenomics research described earlier. A key question that must be addressed is which organisms are present in a sample, and in what phase of growth or dormancy are they? As a result of these concerns, a small ABRF study was conducted in 2012 that focused on addressing 2 areas: first, comparing DNA extraction efficiencies on a known bacterial mix using different methods16 and second, investigating methods to increase extraction efficiencies using Polyzyme. Figure 4A shows the species breakdown of a bacterial mix standard developed by the ABRF Nucleic Acids Research Group (NARG). Figure 4B depicts the different DNA yields of this mock community using different DNA extraction kits.

Figure 4.

A 2012 ABRF NARG study on extraction methods. The ABRF NARG developed a mock community standard made up of 1 different organisms (A), showing the breakdown of these organisms’ relative abundances. (B) The extraction yields across different standard commercial extraction kits. The total expected yield (in nanograms of DNA) and cells in the mix were calculated as 450 ng for 1.1 × 108 cells.

With the recognition of the limitations of nucleic acid extraction efficiency, the MGRG investigated alternative methods to increase DNA yields before downstream processing and analyses. These new methods take into account previous ABRF data, data from scientific corporate partners, and current ongoing studies by members of the ABRF MGRG, Metagenomics and Metadesign of the Subways and Urban Biomes International Consortium,17 and International Metagenomics and Microbiome Standards Alliance.18 Standardization of these methods have included the use of Polyzyme, a novel enzyme blend of microbial lytic enzymes that digest cell-wall components and allow for more efficient lysis of the resulting sphearoplasts or protoplasts. Polyzyme was originally designed by S.T. in 2006 and further refined by MilliporeSigma (Billerica, MA, USA) and includes 6 enzymes that specifically target the cell wall of bacteria, yeast, and fungi [see MilliporeSigma MetaPolyZyme]. This, when used in combination with the XMP multifaceted DNA extraction method that uses hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide, SDS, phenol chloroform, and magnetic beads, proves increased recovery of high MW DNA on many sample types (Fig. 5) needed for third-generation sequencing platforms. This research is still underway, and efficiency data will be published in a future manuscript.

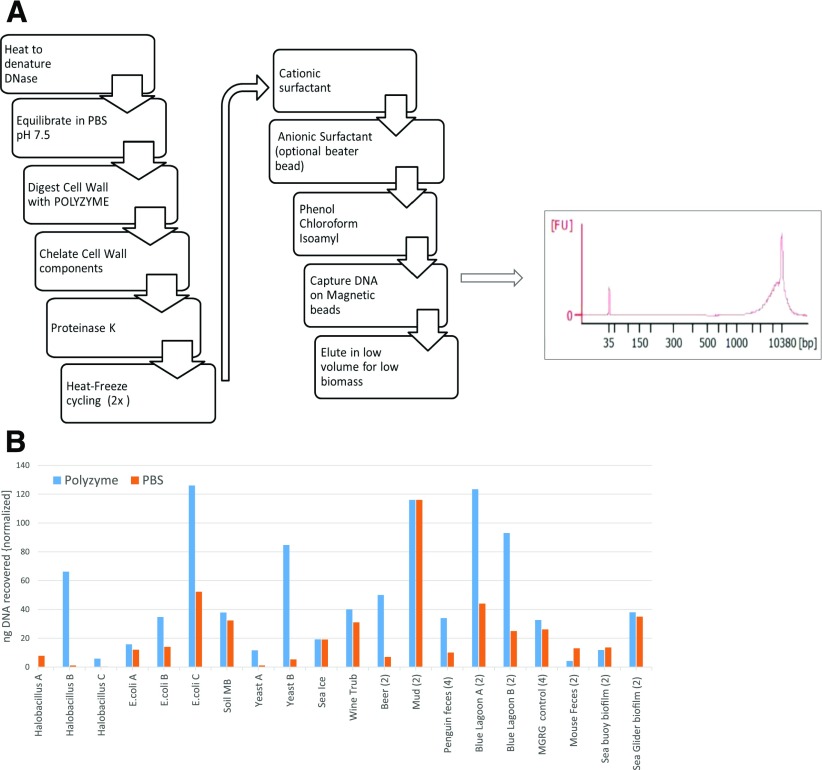

Figure 5.

MGRG Polyzyme mixture workflow and extraction results. (A) Omega Bio-tek DNA extraction method to produce longer fragments of DNA suitable for NGS techniques, such as Pacific Biosciences and Oxford Nanopore Technologies. (B) DNA extraction results for samples treated with the lytic enzyme mix, called Polyzyme, and compared with a no-enzyme control or lysozyme. FU, fluorescent units; Soil MB, Soil MoBio kit.

DEVELOPMENT OF MICROBIAL REFERENCE STANDARDS

Another major challenge for metagenomics and microbiome research is the lack of microbial reference standards and controls for determination of protocol efficiencies for DNA extraction, DNA sequencing, and bioinformatics. The ABRF MGRG is working with the National Institute of Standards and Technology and Genomics Standard Consortium (GSC) to design reference standards for this application. Standardized mock “communities” can serve as positive controls for microbiome and metagenomics studies, allowing researchers to evaluate the reliability and limitations of their results and interpretations. The MGRG has developed 3 Class I microbial reference standards that are distributed by the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA; Table 2). These standards are composed of Bio-safety level 1 organisms of differing Gram reaction and guanine-cytosine content. Class I genomes are the simplest to sequence and assemble and can be applied to all sequencing platforms.19

TABLE 2.

Bacterial species used in the 3 genomic DNA microbial reference standards developed by the ABRF MGRG and XMP

| Organism | Designation | Gram reaction | Genome size, Mb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus epidermidis PCI 1200 | ATCC 12228 | + | 3.50 |

| Chromobacter violaceum NCTC 9757 | ATCC 12472 | − | 2.75 |

| Micrococcus luteus NCTC 2665 | ATCC 4698 | + | 3.17 |

| Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis TAC125 | ATCC 35231 | − | 4.04 |

| Haloferax volcanii DS2 | ATCC 29605 | + | 4.11 |

| Bacillus subitilis subsp. Subtilis str. 168 | ATCC 23857 | + | 5.81 |

| Halobacillus halophilus DSM 2266 | ATCC 35676 | + | 5.55 |

| Escherichia coli K-12 substr. MG1655 | ATCC 700926 | − | 5.58 |

| Entercoccus faecalis OG1RF | ATCC 47077 | + | 3.57 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens F113 | ATCC 13525 | − | 8.68 |

COMPUTATIONAL ANALYSES

Figure 6 summaries an example of the workflow of one XMP site: Lake Hillier, Australia. After the wet lab component and sequencing are complete, the sequence reads were analyzed using a specially developed XMP bioinformatics pipeline, which includes 3 major components: 1) taxa classification, 2) functional analysis, and 3) novel molecule discovery. Not surprisingly, pipeline challenges exist, as some of the organisms have not been described, sequenced, or detected previously using molecular techniques and therefore, lack reference genomic data. To address this challenge, the bioinformatics team is working on a pipeline strategy that includes an ensemble approach of current taxa classification and quantification analytics to ensure a thorough and comprehensive examination of the samples. Moreover, a database is being constructed of all unmapped, uncharacterized sequences, which can be used for future queries. Novel assemblies of synthetic metagenomes and related metadata, known as genomes from metagenomes (GFM), as well as minimum information about extracted GFM, will be considered for deposition into the National Center for Biotechnology Information databank where possible.20–22

Figure 6.

XMP workflow. Each site is sampled in triplicate at multiple locations for both culture and nucleic acid (DNA and RNA) extraction and sequencing. All data are then run through bioinformatics analysis for the following: 1) taxa classification, 2) functional analysis, and 3) novel molecule discovery. JGI, Joint Genome Institute (Walnut Creek, CA, USA).

The concept of a complete molecular profile of each site is an important goal of the XMP and the primary reason for using shotgun whole-genome sequencing. To that end, the functional analysis component will include searching for abundant functional biomolecular pathways, as well as screening for antimicrobial resistance genes and markers. Moreover, one of the more exciting aspects of the XMP bioinformatics analysis is the search for novel gene clusters and molecules that can be used for drug development, such as new antibiotics. MetaBGC is an algorithm developed by the M.D. lab for the discovery of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), which will be used on unassembled or minimally assembled complex metagenomic data and cultured and uncultured microbes.23 The application of the MetaBGC pipeline previously has been demonstrated successfully on the New York City PathoMap datasets5 by detecting novel and predicted thiopeptide BGCs on steel subway railings after Hurricane Sandy.17

CONCLUSION

The XMP is helping to make unique contributions to the field of microbiome and metagenomics research, specifically in new methods and product development. As extremophilic samples are extraordinarily difficult to work with, they require new approaches that can be applied to other microbiome projects: both small contributions, such as development of nucleic acid-free reagents, standards, and protocol, or complex questions, such as discovering clues to synthetic gene clusters or new antibiotics. Nonetheless, discoveries made in the field of microbiome will have a major impact on understanding health; the way we handle food; the way we build buildings, subways, boats, and airplanes; or disease transmission, by comprehending the metagenomics of biofilms, for example.17 Regardless of the area of research, the field of microbiome research remains one of the fastest growing and most exciting areas of biologic research today, with possibly the most significant discoveries yet to come.

AUTHORSHIP

C.E.M. and S.T. cofounded and led the MGRG and XMP. E.A. helped coordinate the XMP, especially regarding analysis of samples. T.M.R. and A.M. manage the XMP website (www.extrememicrobiome.org). E.A., S.T., and C.E.M. led the writing of the manuscript. R. Colwell, S.S.J., T.M.R., N.K., D.B., A.M., K.M., and S.A. provided critical manuscript edits, and S.A. helped format and finalize the manuscript for submission. S.J.G., S.J., S.S.J., D.K. I.C.H., K.M., F.G., E.J., and S.T. are responsible for sample collection, logistics, and technical arrangements at remote sites. E.A. A.M., N. Ajami, J.R.C., R. Colwell, S.J.G., M.D., J.F., N.G., M.S., K.T., and C.E.M. provided complex bioinformatics analysis. D.A.B., D.B., N. Alexander, N.B., J. Hoffman, J. Hyman, J.L., S.L., N.G-R., K.T., T.M.R., K.M., J.P., S.T., and E.Z. preformed the lab processing. N. Alexander, N.G-R., S.J.G., S.T., K.M., K.T., I.C.H., T.M.R., and C.E.M. provided Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Illumina, or Pacific Biosciences sequencing services. L.S. and N.K. led the GSC and provided technical guidance and support. T.H. is the Executive Board liaison to ABRF. The manuscript was reviewed and approved by all authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the ABRF for hosting the XMP through the MGRG subcommittee. The authors thank Chuan-Yu Hsu at Mississippi State University; Steve Simpson, Feseha Abebe-Akele, Jordan Ramsdell, and Krystalynne Morris at University of New Hampshire; John Lizamore and Don Cater at Department of Parks and Wildlife (Western Australia); Susannah Tringe from the Joint Genome Institute for technical input and guidance during the initial assembly of the consortium; and Robert Prill at IBM for bioinformatics support (MegaBlast). All work related to XMP has been done solely by in-kind contributions through the research members and associated core labs. All materials for extraction, sequencing, and analysis have been contributed by the devoted corporate research partners of XMP, including Mostafa Ronaghi, Rob Cohen, and Clotilde Teiling at Illumina; Fiona Stewart at New England Biolabs; Adam Morris at Bioo Scientific; Mike Farrell and Ken Guo at Omega Bio-tek; Ryan Kemp at Zymo Research; Sam Minot at One Codex; Manoj Dadlani and Nur Hasan at CosmosID; Anjali Shah and Abizar Lakdawalla at Thermo Fisher Scientific; and Thomas Juehne, George Yeh, and Robert Gates at MilliporeSigma. The authors give special thanks to George Kourounis for collection of samples from the Darvaza crater “Door to Hell,” Turkmenistan. The authors also thank Michael Micorescu from Oxford Nanopore Technologies for designing special software for the XMP and helping with work in Antarctica. The authors thank Tarun Khurana at Illumina and Mike Farrell at Omega Bio-tek for agreeing to help test the Polyzyme. The authors thank the Epigenomics Core of Weill Cornell Medicine, funding from Starr Cancer Consortium grants (I7-A765, I9-A9-071), Irma T. Hirschl and Monique Weill-Caulier Charitable Trusts, Bert L and N Kuggie Vallee Foundation, WorldQuant Foundation, Pershing Square Sohn Cancer Research Alliance, NASA (NNX14AH50G, NNX17AB26G), U.S. National Institutes of Health (R25EB020393, R01NS076465, R01AI125416, R01ES021006), Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1151054), and Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (G-2015-13964).The authors thank Europlanet 2020 RI from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, under grant agreement No 654208 funded Danakil work, for the Ethiopian Hot Springs.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have read and understood the Journal of Biomolecular Techniques’ policies on declaration of interests and herein declare the following interests: N.Greenfield is employed by and retains ownership in Reference Genomics (One Codex). R. Colwell is the founder of CosmosID.

REFERENCES

- 1.NIH HMP Working Group The NIH Human Microbiome Project. Genome Res 2009;19:2317–2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert JA, Jansson JK, Knight R. The Earth Microbiome Project: successes and aspirations. BMC Biol 2014;12:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lax S, Smith DP, Hampton-Marcell J, et al. Longitudinal analysis of microbial interaction between humans and the indoor environment. Science 2014;345:1048–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith D, Alverdy J, An G, et al. The Hospital Microbiome Project: Meeting Report for the 1st Hospital Microbiome Project Workshop on sampling design and building science measurements, Chicago, USA, June 7th–8th 2012. Stand Genomic Sci 2013;8: 112–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afshinnekoo E, Meydan C, Chowdhury S, et al. Geospatial resolution of human and bacterial diversity with city-scale metagenomics. Cell Syst 2015;1:72–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rampelotto PH. Extremophiles and extreme environments. Life (Basel) 2013;3:482–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalmaso GZ, Ferreira D, Vermelho AB. Marine extremophiles: a source of hydrolases for biotechnological applications. Mar Drugs 2015;13:1925–1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dittami SM, Tonon T. Genomes of extremophile crucifers: new platforms for comparative genomics and beyond. Genome Biol 2012;13:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brock TD, Freeze H. Thermus aquaticus gen. n. and sp. n., a nonsporulating extreme thermophile. J Bacteriol 1969;98:289–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chien A, Edgar DB, Trela JM. Deoxyribonucleic acid polymerase from the extreme thermophile Thermus aquaticus. J Bacteriol 1976;127:1550–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antranikian G. (ed): Extremophiles: Microbial Life Under Extreme Conditions. Tokyo, Japan: Springer, 1997–2017.

- 12.Gittel A, Bárta J, Kohoutová I, et al. Distinct microbial communities associated with buried soils in the Siberian tundra. ISME J 2014;8:841–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mason OU, Scott NM, Gonzalez A, et al. Metagenomics reveals sediment microbial community response to Deepwater Horizon oil spill. ISME J 2014;8:1464–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ABRF MGRG/XMP Consortium Next generation sequencing and the Extreme Microbiome Project (XMP). Next Gener Seq Appl 2015;2:115. [Google Scholar]

- 15.TRIzol Reagent and TRIzol LS Reagent Technical Note. Catalog number: 10296028. Waltham, MA, USA: Thermo Fisher Scientific.

- 16.The Importance of DNA Extraction in Metagenomics: The Gatekeeper to Accurate Results! ABRF 2013 Research Study Bethesda, MD, USA: Nucleic Acids Research Group, https://abrf.org/sites/default/files/temp/RGs/NARG/narg_rg4_holbrook.pdf.

- 17.MetSUB International Consortium The Metagenomics and Metadesign of the Subways and Urban Biomes Consortium (MetaSUB) International Consortium inaugural meeting report. Microbiome 2016;4:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.IMMSA Mission Statement Gaithersburg, MD, USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology, https://www.nist.gov/mml/bbd/immsa-mission-statement

- 19.Koren S, Harhay GP, Smith TP, et al. Reducing assembly complexity of microbial genomes with single-molecule sequencing. Genome Biol 2013;14:R101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MetaHIT Consortium Identification and assembly of genomes and genetic elements in complex metagenomic samples without using reference genomes. Nat Biotechnol 2014;32:822–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sangwan N, Xia F, Gilbert JA. Recovering complete and draft population genomes from metagenome datasets. Microbiome 2016;4:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruby JG, Bellare P, Derisi JL. PRICE: software for the targeted assembly of components of (Meta) genomic sequence data. G3 (Bethesda) 2013;3:865–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donia MS, Cimermancic P, Schulze CJ, et al. A systematic analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters in the human microbiome reveals a common family of antibiotics. Cell 2014;158:1402–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]