Abstract

Background

Pharmacies in Bangladesh serve as an important source of health service. A survey in Dhaka reported that 48% of respondents with symptoms of acute respiratory illness (ARI) identified local pharmacies as their first point of care. This study explores the factors driving urban customers to seek health care from pharmacies for ARI, their treatment adherence, and outcome.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 100 selected pharmacies within Dhaka from June to December 2012. Study participants were patients or patients’ relatives aged >18 years seeking care for ARI from pharmacies without prescription. Structured interviews were conducted with customers after they sought health service from drug sellers and again over phone 5 days postinterview to discuss treatment adherence and outcome.

Results

We interviewed 302 customers patronizing 76 pharmacies; 186 (62%) sought care for themselves and 116 (38%) sought care for a sick relative. Most customers (215; 71%) were males. The majority (90%) of customers sought care from the study pharmacy as their first point of care, while 18 (6%) had previously sought care from another pharmacy and 11 (4%) from a physician for their illness episodes. The most frequently reported reasons for seeking care from pharmacies were ease of access to pharmacies (86%), lower cost (46%), availability of medicine (33%), knowing the drug seller (20%), and convenient hours of operation (19%). The most commonly recommended drugs were acetaminophen dispensed in 76% (228) of visits, antihistamine in 69% (208), and antibiotics in 42% (126). On follow-up, most (86%) of the customers had recovered and 12% had sought further treatment.

Conclusion

People with ARI preferred to seek care at pharmacies rather than clinics because these pharmacies were more accessible and provided prompt treatment and medicine with no service charge. We recommend raising awareness among drug sellers on proper dispensing practices and enforcement of laws and regulations for drug sales.

Keywords: drug sellers, pharmacy, acute respiratory illness, dispensing practice, health care seeking, customers

Introduction

Acute respiratory infection (ARI) is a leading cause of death and accounted for 16% of the 5.9 million global deaths among children aged >5 years during 2000–2015.1 ARI causes substantial morbidity and mortality among adults and children, with 97% of the world’s new pneumonia cases occurring in low-income countries.2–4 In Bangladesh, a lower middle-income country with scarcity of health care providers,5 ARI is the major cause of mortality in children aged <5 years, accounting for an estimated 28% of deaths.6 A study in rural Bangladesh estimated the ARI incidence at 5.5 episodes per child-year, with acute lower respiratory infection occurring at a rate of 0.2/year among children aged <5 years.7 This ARI burden is associated with substantial economic costs.8,9

In Bangladesh, people with ARI frequently seek care at local pharmacies. A national survey estimated that for 22% of children with ARI, their relative sought care at pharmacies for their illness episode.10 Furthermore, a community survey in Bangladesh reported that 30% of cases with influenza-like illness (ILI; with symptoms of ARI as sudden onset of subjective fever, cough, or sore throat) sought care at pharmacies.11 Another survey in Dhaka reported that 48% of respondents with ILI sought care at local pharmacies as a first point of contact.12 In rural Bangladesh, 46% of patients sought treatment from drug sellers (a person working at a pharmacy recommends and sells drugs, and the person may or may not have any formal training in pharmacy practice) in pharmacies for any kind of ailment and 77% preferred to first visit a pharmacy for relief from fevers and colds.13

In low- and middle-income countries, pharmacies have been identified as an important source for medication and health advice.14,15 Although pharmacies are a source of health service for diverse socioeconomic groups, they are an especially important health care option for low-income populations or those who lack formal education.15,16 Drug sellers in both licensed (government approved) and unlicensed (not government approved) pharmacies are accustomed to dispensing medicine and health advice to health care-seeking customers for common ailments without requiring a prescription from a physician.15,17 Licenses are provided to drug sellers by the Directorate General of Drug Administration when they have completed a grade C pharmacy degree (ie, 3 months course) to legally dispense drugs from pharmacy.18

A 2007 national survey revealed that drug sellers working in pharmacies comprised 8% of the total population of health care providers in Bangladesh and 16% of health care providers in urban areas. Most (95%) of the drug sellers were unregulated and lacked formal qualifications in their field. None of the drug sellers surveyed had received any training in health care or drug dispensing.15 Despite their lack of training, drug sellers were two times more likely to provide treatment to the population when compared to physicians.5

There are limited data about why people prefer to seek care from drug sellers in an urban setting, where both public and private hospitals as well as qualified physicians are available. In this study, we surveyed people with ARI seeking care at pharmacies without prescriptions to identify the factors driving customers to seek such care and describe the medications provided by the drug sellers, adherence to treatment recommendations, and illness outcomes. Our study aimed to provide information about the use of pharmacies for health care and dispensing practices for engaging drug sellers for ARI prevention and control.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a cross-sectional pilot survey among 100 selected pharmacies within Dhaka city from August to November 2012. As there were no local data about the proportion of people seeking care at pharmacies, we arbitrarily chose to sample 100 pharmacies. We deployed two field research officers (FROs) from June to July 2012 to select 10 pharmacies from each of the 10 administrative zones in Dhaka city using 10 randomly generated GPS points for each zone and identifying the closest pharmacy to each point based on the following eligibility criteria. They attempted to enroll any licensed or unlicensed pharmacy that had been in operation for >5 years because we believe that such pharmacies would have built a customer base for our target sample size. In addition, the FROs sought pharmacies located >100 m from any government or private medical college or hospital to avoid customers with a prescription from a physician.

Participant selection criteria

The FROs explained the drug sellers of the selected pharmacies that they would wait in the pharmacy to identify customers seeking health care for themselves or a sick relative with ARI without a physician’s prescription to interview the customers and understand their reasons for seeking care at pharmacies. Immediately after the ARI customers had been attended by the drug sellers, the FROs met the customers to interview them. We sought study participants aged >18 years because we believed that customers in this age group would be able to provide the most reliable survey information.

The FROs enrolled health care seekers as ARI cases if they reported that they or the individual for whom they were seeking care had a runny nose, nasal congestion, cough, or respiratory distress with or without fever.19 The FROs were positioned at each pharmacy for at least 3 hours a day during three randomly selected days of the month to interview at least three customers on each day from each pharmacy.

Data collection

After the customers obtained treatment recommendations and purchased medicine, the FROs approached the customers to seek their informed consent to participate in the survey, and after receiving consent, they completed a standardized survey about their choice of health care. The FROs also recorded the customers’ demographics, including their age, education, monthly income, health care-seeking history, symptoms, duration of recent respiratory illness, and the medicines dispensed by the drug sellers. An episode was considered to be new if the patient was symptom free in the preceding 7 days.19 The FROs collected the customers’ cell phone number during the interviews to call them 5 days later and determine their adherence to treatment recommendations and ARI outcomes (eg, improved symptoms or sought additional care).

Statistical analysis

We used Stata version 13 for cleaning, coding, and analyzing the data. We described the data using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and dispensed drugs and median and interquartile range (IQR) for nonparametric data. During our analysis, we categorized the respiratory symptoms into the following three respiratory syndromes: 1) uncomplicated afebrile ARI (runny nose or nasal congestion and/or cough without a history of subjective fever); 2) uncomplicated febrile ARI (a history of subjective fever with runny nose, nasal congestion, or cough); and 3) complicated ARI (respiratory distress with runny nose or nasal congestion and/or cough). We used Fisher’s exact test and two-sample tests for proportion to compare the use of antibiotics depending on the respiratory syndrome and age category of the patients.

Ethics consideration

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b). Moreover, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) relied on icddr,b’s IRB review and provided assistance and guidance with technical aspects of this study.

Results

The FROs enrolled 302 ARI customers at 76 of the 100 study pharmacies. In all, 24 pharmacies did not have customers seeking care for ARI during the hours in which the FROs were at pharmacies.

Health care-seeking behavior

Among the 302 ARI customers, 186 (62%) sought care for their own illness and 116 (38%) on behalf of a sick relative. Only 29 (10%) sought care from other health care providers before visiting the pharmacy for the illness. Among these 29 customers, 18 (62%) sought care from another pharmacy and 11 (38%) from physicians. All 29 reported that they sought care again because their illness had not improved after the first visit to a provider.

Demographics

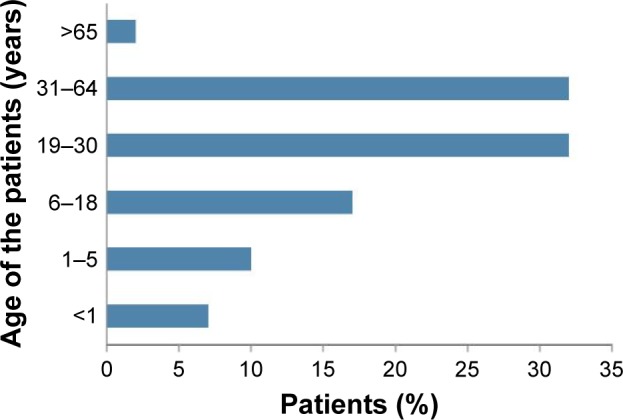

Most customers (215; 71%) and most patients (216; 72%) were males. The median age of the customers was 30 years (IQR: 24–40 years), median age of the sick relative for whom customers sought health care was 7 years (IQR: 2–15 years), and median age of the customers who sought health care for their own illness was 30 years (IQR: 24–40 years; Figure 1). Customers had a median 8 years of education (IQR: 3–12 years) and a median monthly income of 158 USD (IQR: 127–253 USD; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Age of the patients seeking health care from the pharmacies for acute respiratory illness without any prescription from a physician within Dhaka city from August to November 2012.

Table 1.

Education level and monthly income of the customers seeking health care from the pharmacies for acute respiratory illness without any prescription from a physician within Dhaka city from August to November 2012

| Characteristics | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Customers’ education level (years of education), n=302 | |

| No formal education | 42 (14) |

| 1–5 | 74 (24) |

| 6–10 | 109 (36) |

| 11–12 | 45 (15) |

| >12 | 32 (11) |

| Customers’ monthly income (USD), 1 USD = 79 BDT, n=302 | |

| <63* | 9 (3) |

| 64–126 | 110 (36) |

| 127–253 | 109 (36) |

| 254–379 | 35 (12) |

| 380–633 | 30 (10) |

| >633 | 9 (3) |

Notes: Customers’ education, median (IQR): 8 years (3–12 years); customers’ monthly income, median (IQR): 158 USD (127–253 USD).

Bangladeshis living in poverty – defined as an income of <USD2/day.32

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

ARI symptoms

The customers sought health care from the pharmacies a median of 3 days (IQR: 2–3 days) after ARI symptom onset; only 146 (48%) customers sought care for ARI within 2 days of symptom onset. Among customers seeking health care, 234 (78%) had runny nose, 209 fever (69%), 153 cough (51%), 75 myalgia (25%), 35 sneezing (12%), 29 nasal congestion (10%), 28 headache (9%), nine sore throat (3%), and three self-reported respiratory distress (1%).

Driving factors for seeking health care from pharmacy

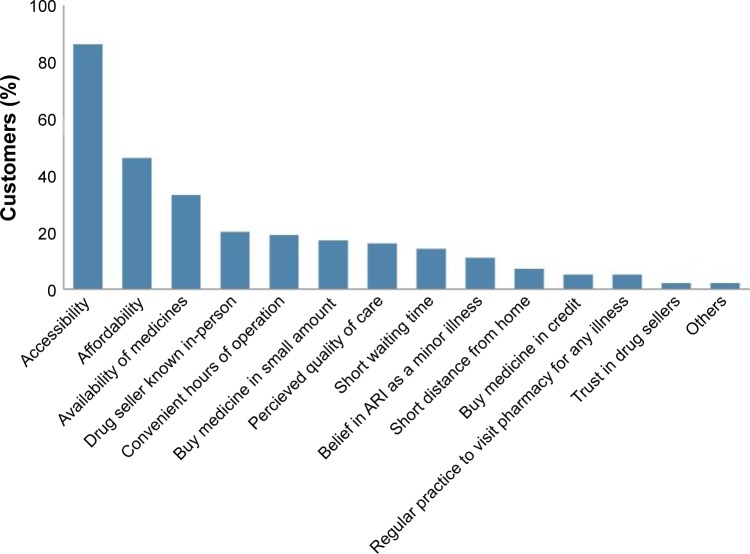

The respondents identified accessibility to the pharmacies (86%), affordability (46%), availability of medicines (33%), personally knowing the drug seller (20%), convenient hours of operation (19%), ability to purchase medicine in small amounts (17%), belief in quality of care (16%), short waiting time (14%), belief that ARI is a minor illness (11%), and short distance (7%) as reasons for seeking care from pharmacies rather than physicians (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Factors driving customers’ decision to seek health care from pharmacies for acute respiratory illness in Dhaka city, Bangladesh, from August to November 2012.

Abbreviation: ARI, acute respiratory illness.

Recommended treatment

A median of two (IQR: two to three) drugs were dispensed per customer for ARI symptoms; three or more drugs were dispensed to 127/302 (42%) customers. The most commonly sold drugs were acetaminophen dispensed in 76% (228) of visits, antihistamines in 69% (208), antibiotics in 42% (126), and cough syrups in 17% (51; Table 2). Antihistamines were dispensed in 39% (20/51) of children <5 years of age. Children aged <5 years were more likely to receive antibiotics (36/51; 71%) compared to adults (69/200; 35%) (P<0.001); patients with subjective fever (101/207; 49%) were more likely to receive antibiotics compared to those without fever (22/92; 24%; P<0.001; Table 3).

Table 2.

Drugs dispensed to customers seeking health care for acute respiratory illness from the selected pharmacies in Dhaka city, Bangladesh, from August to November 2012

| Dispensed drugs | Total drugs (n=722), % |

Customers (n=302), % |

|---|---|---|

| Paracetamol | 32 | 76 |

| Non-sedating antihistamine | 23 | 56 |

| Cough expectorants | 6 | 15 |

| Sedating antihistamine | 5 | 13 |

| Bronchodilator | 4 | 8 |

| Ulcer healing drugs | 3 | 8 |

| Herbal cough syrup | 3 | 7 |

| Prophylactic to bronchial asthma | 2 | 5 |

| Cough suppressants | 1 | 2 |

| Nasal decongestant | 1 | 2 |

| Steroid (oral) | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| Others | 3 | 6 |

| Antibiotics (n=126) | 18 | 42 |

| Azithromycin | 37 | |

| Amoxicillin | 20 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 19 | |

| Cefradine | 10 | |

| Levofloxacin | 5 | |

| Cefixime | 5 | |

| Other antibiotics | 4 |

Notes: Cough expectorant: bromhexine HCl, ambroxol HCl, and pseudoephedrine with guaifenesin; cough suppressant: dextromethorphan HBr with pseudoephedrine; and antivirals (n=0).

Abbreviations: HCl, hydrochloride; HBr, hydrobromide.

Table 3.

Age-specific antibiotics dispensed to customers seeking health care for different respiratory syndromes from pharmacies in Dhaka city, Bangladesh, from August to November 2012

| ARI syndrome | Patients (N=302), n (%) |

Antibiotics dispensed to patients aged 0–5 years (%) | Antibiotics dispensed to patients aged 6–18 years (%) | Antibiotics dispensed to patients aged >18 years (%) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncomplicated afebrile ARI | 92 (30) | 7/15 (47) | 4/13 (31) | 11/64 (17) | P≤0.04 |

| Uncomplicated febrile ARI | 207 (69) | 27/34 (79) | 17/38 (45) | 57/135 (42) | P≤0.00 |

| Complicated ARI | 3 (1) | 2/2 (100) | 0 | 1/1 (100) | – |

| P-value* | P≤0.00 |

Note:

Fisher’s exact test.

Abbreviation: ARI, acute respiratory illness.

Treatment outcome

Five days after the pharmacy visit, a follow-up interview was conducted over phone with 297 (98%) customers; five (2%) customers could not be reached for follow-up. After purchasing medication from the drug sellers, 270 (91%) patients completed their course after a median of 3 days (IQR: 1–3 days), 27 (9%) did not follow the recommendation and stopped taking medicine, and three (1%) shared medicine with others. Of these 27 patients who did not complete their course of medicine, 17 (63%) had been dispensed antibiotics. The reported reasons for not completing the course of medicine included improved health (16/27; 59%), no improvement (6/27; 22%), purchase of insufficient medicine (2/27; 7%), and other reasons (ie, sharing medicine, generalized weakness after taking medicine, and forgetting to take medicine; 3/27; 12%). Among the 302 customers who purchased medicine, 256 (86%) were feeling better at a median of 8 days (IQR: 7–8 days) from symptom onset. In all, 35 (12%) sought further treatment for the same illness episode from a health care provider. Among these 35 patients, 20 (57%) again sought treatment from a pharmacy (eight from the same pharmacy and 12 from another pharmacy), 10 (29%) from a physician, and five (14%) from an outpatient clinic. None of the 297 participants were hospitalized or sought emergency medical care up to the follow-up on the sixth day.

We identified only three (1%) patients with self-reported complicated ARI; all three received antibiotics from the pharmacy and felt better after treatment. One of the three patients was an adult male aged 61 years who sought care from the pharmacy as a first point of care for the illness episode. The other two were pediatric patients aged 5 and 14 months for whom their mothers sought care at 4 and 6 days after illness onset, respectively. Both sought treatment previously for these illness episodes, one from another pharmacy and the other from a physician before coming to the participating pharmacy.

Discussion

In this study, we identified easy access, low cost, availability of medicine, personally knowing the drug seller, convenient hours of operation, belief in treatment efficacy, short waiting time, perception of ARI as a minor illness, and proximity as reasons for seeking health care from pharmacies for ARI.

Ease of access to the pharmacies was an important reason for seeking health care for ARI. This finding is consistent with studies from other countries showing the importance of accessibility in health care-seeking behaviors.20–22 A survey on health care-seeking behaviors among slum dwellers within Dhaka city and a study in Nigeria reported close distance to one’s home as a motivation for preferring pharmacies for primary source of health care.21,23

The second most common reason for seeking health care from a pharmacy in our study population was cost. Patients who seek care from physicians in Bangladesh pay for their consultancy and then again when purchasing the physician’s recommended medicine. Drug sellers recommend and sell medicines for an illness episode without requiring payment for providing a treatment recommendation. A survey within Dhaka city reported that median cost of seeking health care for ILI was much lower in pharmacies (1.5 USD) when compared to visit to a physician’s chamber (5.6 USD) or an outpatient department (4.6 USD).12 Similar to our study, seeking health care from a pharmacy was also reported as a method to reduce medical expenses among the population in Vietnam and Nigeria.21,24

Customers frequently reported convenience of hours of operation as an important factor in seeking care at pharmacies rather than physicians because customers did not want to take time off work to go to a clinic or medical office. Long wait times at government health facilities (57.1±4.2 min) are associated with dissatisfaction among health care seekers in Bangladesh.25 Convenient hours of operation and minimal waiting times were also important factors in determining medical service used in other countries like Vietnam.24 The study in Nigeria reported time saved as a result of rapid action, including prompt treatment recommendation, as a common motivating factor for customers seeking health care from pharmacies.21

Furthermore, our study found customers’ belief in the quality of care provided by the drug sellers and faith in their treatment efficacy as motivating factors to seek treatment from pharmacies. Some of our study participants relied on community drug sellers because they knew them personally and seemed to trust them for the care they provided. Moreover, customers also perceived ARI as a minor illness that could be treated by drug sellers and did not require physician consultation. The majority of patients with ARI typically present with cough, congested/runny nose, body ache, headache, and sore throat, with or without fever.26 The study in rural Bangladesh reported that 96% of the ARI were limited to the upper respiratory tract.7 Indeed, most participants in our study sought care for reported uncomplicated acute respiratory illnesses that are unlikely to progress to complicated respiratory illness and could be treated symptomatically. Our study was consistent with studies in Bangladesh and Nigeria that also identified customers’ trust in drug sellers’ recommended treatment as a factor to seek care from pharmacies.13,21

People with ARI symptoms frequently have self-limiting viral illnesses that do not require antibiotics.26 While a substantive proportion (18%) of people with severe ARI also seek care at pharmacies in rural Bangladesh,11 most (99%) patients seeking care at pharmacies had symptoms compatible with uncomplicated ARI; only 1% reported symptoms compatible with complicated ARI such as respiratory distress. Antibiotics, however, were dispensed to two out of every five customers seeking care for ARI without any clear indication. The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests acetaminophen as the appropriate drug choice for children aged <5 years with a common cold (cough and congested/runny nose) and fever.27,28 The guidelines also suggest remedies for coughing relief and when to follow-up with a clinician if patients develop danger signs of complicated respiratory illness.27,28 According to the guidelines, only children diagnosed with pneumonia should receive antibiotics (eg, amoxicillin) prescribed by trained community health care providers.27,28 In our study, drug sellers provided 71% of children aged <5 years with antibiotics; an additional 39% were given antihistamines, a practice discouraged by the WHO guideline. Community health care providers should refer suspected severe pneumonia patients to a health facility for evaluation by a physician for possible antibiotic treatment.27,28

Our study demonstrates the frequent sale of antibiotics for patients with ARI. According to Bangladesh’s 2005 National Drug Policy, drug sellers are prohibited from dispensing any antibiotics without a physician’s prescription.18 Such practices suggest that financial motivation might supersede drug sellers’ concerns about the potential risks of inappropriate antibiotic use. The widespread inappropriate use of antibiotics for what often are self-limited viral illness contributes to the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance, especially in densely populated countries.29 Moreover, the excessive and inappropriate use of antibiotics is an unnecessary cost to customers.

To address this inappropriate practice, the public health community could enlist and train drug sellers to provide appropriate symptomatic care and timely referrals of customers seeking care for ARI. A literature review about interventions to enhance the role of pharmacies in low- and middle-income countries demonstrated that educational intervention can be effective in improving drug sellers’ prescribing practices for common ailments.30 Although there have been mixed results in the efficacy of educational interventions to improve dispensing practices,31 health officials should explore which interventions could be adapted and tested in Bangladesh.

There are several limitations in this study. We did not interview customers who attended pharmacy with a physician’s prescription for ARI or sought to purchase a particular medication. Interviewed customers had already decided to consult pharmacies about their respiratory illnesses and probably would have been more likely to report the benefits of seeking care at pharmacies than people who chose to seek care elsewhere. Approximately one-third (38%) of customers sought care on behalf of a sick relative; drug sellers might have recommended different care if patients had been physically present at the pharmacy. We limited data collection to pharmacies >100 m from a medical college or hospital in order to better focus on typical drug seller practices. This decision, however, might have introduced bias in our sample. Our small sample size limited our ability to assess how drug sellers would have interacted with customers who sought care for severely ill family members. We did not quantify wait times, proximity to customers’ home, and transportation to the drug seller and clinics, which could have helped to better describe the apparent convenience and cost savings of seeking care at pharmacies versus other health care providers. Moreover, we did not know the outcome of the five patients whom we could not reach during follow-up.

Conclusion

Patients seeking care at pharmacies in Dhaka city received treatment recommendations promptly and bought medicines without having to pay for an additional consultation fees. Respondents seem to believe that pharmacies were a suitable substitute for a physician when seeking care for ARI. The treatment recommendations for antibiotics, however, often seemed excessive. There might be utility in raising awareness about recommended dispensing practices, regulating drug sales, and enforcing licensing among those who operate pharmacies. Further studies should explore the effectiveness of such interventions in the context of Bangladesh.

Acknowledgments

This research study was funded by CDC, grant number CDC Cooperative U01/CI000628-03. icddr,b acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of CDC to its research efforts. icddr,b is also grateful to the governments of Bangladesh, Canada, Sweden, and the UK for providing core/unrestricted support. The abstract of this article was presented at the ICEID 2015 Conference named “Factors driving customers to seek health care in pharmacies for acute respiratory illness, a pilot study in Dhaka City, Bangladesh” as a poster presentation with interim findings. The poster’s abstract was published in “International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases 2015 Poster and Oral Presentation Abstracts”, http://www.iceid.org.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.UNICEF Committing to Child Survival: A Promise Renewed. 2015. [Accessed February 17, 2017]. (Progress Report 2015). Available from: https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/APR_2015_Key_Findings_8_Sep_15.pdf.

- 2.Isturiz RE, Luna CM, Ramirez J. Clinical and economic burden of pneumonia among adults in Latin America. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(10):e852–e856. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.02.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudan I, Boschi-Pinto C, Biloglav Z, Mulholland K, Campbell H. Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(5):408B–416B. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.048769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker CLF, Rudan I, Liu L, et al. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1405–1416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed SM, Hossain MA, RajaChowdhury AM, Bhuiya AU. The health workforce crisis in Bangladesh: shortage, inappropriate skill-mix and inequitable distribution. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9(3):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–2013, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385(9966):430–440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaman K, Baqui A, Sack R, Bateman O, Chowdhury H, Black R. Acute respiratory infections in children: a community-based longitudinal study in rural Bangladesh. J Trop Pediatr. 1997;43(3):133–137. doi: 10.1093/tropej/43.3.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhuiyan MU, Luby SP, Alamgir NI, et al. Economic burden of influenza-associated hospitalizations and outpatient visits in Bangladesh during 2010. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2014;8(4):406–413. doi: 10.1111/irv.12254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alamgir NI, Naheed A, Luby SP. Coping strategies for financial burdens in families with childhood pneumonia in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute of Population Research and Training Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011. 2013. [Accessed February 17, 2017]. (Preliminary report NIPORT). Available from: http://www.dghs.gov.bd/licts_file/images/BDHS/BDHS_2011.pdf.

- 11.Azziz-Baumgartner E, Alamgir A, Rahman M, et al. Incidence of influenza-like illness and severe acute respiratory infection during three influenza seasons in Bangladesh, 2008–2010. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(1):12–19. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.090209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ICDDR B. The economic burden of influenza-like illness in Mirpur, Dhaka, during the 2009 pandemic: a household cost of illness study. Health Sci Bull. 2010;8(1):2. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahmood SS, Iqbal M, Hanifi S. Health-seeking behaviour. Health for the Rural Masses. 2009:67–93. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith F. The quality of private pharmacy services in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Pharm World Sci. 2009;31(3):351–361. doi: 10.1007/s11096-009-9294-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed SM, Hossain MA, Chowdhury MR. Informal sector providers in Bangladesh: how equipped are they to provide rational health care? Health Policy Plan. 2009;24(6):467–478. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed SM, Tomson G, Petzold M, Kabir ZN. Socioeconomic status overrides age and gender in determining health-seeking behaviour in rural Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(2):109–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhuiya A. Health for the Rural Masses: Insights from Chakaria. 2009. [Accessed February 17, 2017]. (ICDDR, B). Available from: http://dspace.icddrb.org:8080/jspui/bitstream/123456789/6421/1/FHS_book_Health_for_Rural_Masses.pdf.

- 18.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh . The National Drug Policy. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Homaira N, Luby SP, Petri WA, et al. Incidence of respiratory virus-associated pneumonia in urban poor young children of Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2009–2011. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goel P, Ross-Degnan D, Berman P, Soumerai S. Retail pharmacies in developing countries: a behavior and intervention framework. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42(8):1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00388-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Igun UA. Why we seek treatment here: retail pharmacy and clinical practice in Maiduguri, Nigeria. Soc Sci Med. 1987;24(8):689–695. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90312-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelling SE. Exploring accessibility of community pharmacy services. Innovations Pharm. 2015;6(3):6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute of Health Economics, University of Dhaka Health Care Seeking Behavior of Slum-Dwellers in Dhaka City. 2015. [Accessed February 17, 2017]. (Results of a Household Survey). Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/bangladesh/publications/health_care_seeking_slum_dwellers.pdf.

- 24.Segall M, Tipping G, Lucas H, et al. Health Care Seeking by the Poor In Transitional Economies: The Case of Vietnam. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aldana JM, Piechulek H, Al-Sabir A. Client satisfaction and quality of health care in rural Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(6):512–517. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization . Cough and Cold Remedies for the Treatment of Acute Respiratory Infections in Young Children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization . Pocket Book of Hospital Care for Children. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization . Handbook IMCI: Integrated Management of Childhood Illness. Geneva: Department of Child and Adolescent Health, World Health Organization; 2005. p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Planta MB. The role of poverty in antimicrobial resistance. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(6):533–539. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.06.070019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith F. Private local pharmacies in low- and middle-income countries: a review of interventions to enhance their role in public health. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14(3):362–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wafula FN, Goodman CA. Are interventions for improving the quality of services provided by specialized drug shops effective in sub-Saharan Africa? A systematic review of the literature. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22(4):316–323. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzq022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Bank Group webpage on the Internet. [Accessed February 15, 2017]. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.DDAY.