Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) in the treatment of post-surgical biliary leaks and its efficacy in restoring the integrity of bile ducts. One hundred and fifty-seven patients with a post-surgical biliary leak were treated by means of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. The biliary leak was due to laparoscopic procedures in 114 patients, while 43 patients had postoperative leak following open surgery. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage was performed with an 8- to 10-F catheter, with the side holes positioned proximal to the site of extravasation to divert bile flow away from the leak site. The established biliary leaks at the site of origin were diagnosed at an average of 7 days (range 2–150 days) after surgery. In all cases, percutaneous access to the biliary tree was achieved. In 62 patients, biliary leak completely healed after drainage for 10–50 days (mean, 28 days) while 89 patients underwent surgical reconstruction subsequently. PTBD is a feasible, effective, and safe procedure for the treatment of post-surgical biliary leaks. It is therefore a reliable alternative to surgically repair smaller biliary leaks, while in patients with large defects, it helps prepare patients for surgical reconstruction.

Keywords: Biliary leak, Postoperative, Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD), Benign biliary stricture, Balloon dilatation

Introduction

Bile duct injuries may lead to bile leakage, intraabdominal abscesses, cholangitis, and secondary biliary cirrhosis due to chronic strictures. Postoperative biliary leaks usually occur as a complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy or enterobiliary anastomosis. Depending on the type of injury, management may include endoscopic, percutaneous, and open surgical interventions. They are usually treated by means of either surgical repair or endoscopic biliary drainage [1, 2]. Surgical repair and endoscopic management are, in some cases, either impossible or unsuccessful, particularly in patients with large postoperative biliary duct defects. In these conditions, the bile flow can easily be diverted away from the defect in the bile duct through percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage in the same way that a ureteral leak can be treated using a nephroureteral catheter [2–4].

Materials and Methods

Patients

From 2002 to 2014, 157 patients (104 men and 53 women; age range, 10–72 years; mean, 48 years) with biliary leak were referred to our department and treated by means of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. Biliary extravasation was evidenced through a defect involving the common bile duct (n = 47), the hepaticojejunal anastomosis (n = 34), a biliary radicle (n = 24), and the cystic duct (n = 16); however, in 36 patients, the exact site of biliary leak could not be demonstrated (Fig. 1).

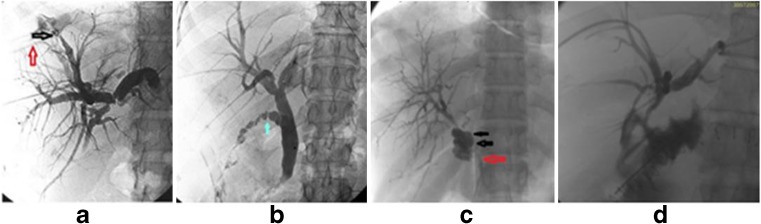

Fig. 1.

Fluoroscopic images showing a spectrum of bile leak. a Percutaneous cholangiogram shows a Strasburg type A bile leak from the peripheral biliary radical (black arrow) communicating with the drain placed in the right pleural cavity (red arrow). b Percutaneous cholangiogram shows a cystic duct blowout (green arrow), Strasburg type A1 bile duct injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. c PTC gram shows a Strasburg type D common bile duct injury (black arrow) with localized accumulation of contrast and visualized distal CBD (red arrow). d Cholangiogram through the pig tail drain shows a bile leak from the hepaticojejunostomy anastomotic site with localized extravasations of contrast

Ninety-seven patients (62 %) had a leak after a bile duct injury from laparoscopic cholecystectomy, while 60 patients (38 %) developed a leak following open surgeries: hepaticojejunostomy associated with Whipple procedure (n = 38), conventional cholecystectomy (n = 19), and repair of choledochal cyst (n = 3). A leak was suspected because of persistent bilious-looking drainage from the surgical drain (n = 131) or because of bile peritonitis (n = 8) or perihepatic biloma detected at postoperative computed tomography (n = 16) or bilious pleural tap (n = 2) (Fig. 1).

Procedure

Percutaneous transhepatic biliary cholangiography was initially performed using a 21-gauge Chiba needle to inject the contrast medium using the right intercostal approach. The right bile ducts are accessed from the midaxillary line with fluoroscopic guidance. The entry site should be at the level of the inferior portion of the right hepatic lobe and along the superior margin of the rib to minimize the risks of pleural transgression and intercostal neurovascular bundle injury, respectively. The left bile ducts are accessed with a subxiphoid approach. A right or left approach for the percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage was chosen depending on biliary anatomy, bile leak topography, and the possibility of puncturing a dilated intrahepatic bile duct. Catheterization of intrahepatic bile ducts was performed in standard fashion. A guide wire was advanced through the biliary system into the duodenum. When this was achieved, an 8–10-Fr biliary drainage catheter was inserted. All drainage procedures were performed with the administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics. In 16 patients, percutaneous drainage of a large perihepatic biloma was also performed, and in 2 patients, an intercostal drainage catheter to drain bilious pleural collection was inserted.

The drainage catheter was positioned within the bile ducts to have the side holes just above the leak. Bilateral biliary drainage was used if the bile leak involved the biliary confluence.

As soon as the postoperative intraabdominal drain output became nil, the catheter was closed to avoid protein and calorie malnutrition and fluid and electrolyte depletion. The catheter was removed when cholangiography showed that the leak had healed without residual stenosis. If there was residual narrowing at the site of extravasation, balloon dilation was performed.

Results

Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage was successful in all the patients. Although a relatively large number of passes were required in some of the patients to opacify a bile duct suitable for catheter placement when duct dilatation was absent, we achieved high technical success rates in patients with nondilated ducts. The intrahepatic bile ducts were dilated in 17 patients (11 %) and nondilated in 140 patients (89 %). A right approach was used in 127 patients (81 %), a left approach was used in 25 patients (16 %), and a bilateral approach was used in 5 patients (3 %).

Two patients developed a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm which was treated with transcatheter embolization, while 1 patient developed bilious pleural effusion which was treated successfully by biliary drainage and pleural pigtail drainage. One patient died because of pulmonary embolism due to associated lower limb deep venous thrombosis which was proven on postmortem.

In 62 patients, biliary leak completely healed after drainage for 10–50 days (mean, 28 days) (Fig. 2a, b) while 89 patients underwent surgical reconstruction (Fig. 3e) subsequently. Six patients died secondary to sepsis. Of the 62 patients, 44 (71 %) had no residual stenosis in the checked cholangiogram before removing the drainage catheter. In 18 patients (29 %), cholangiography performed before withdrawal of the drainage catheter showed the bile duct to be narrowed at the site of the previous leak (Table 1). This stenosis was treated by means of balloon dilation (Fig. 4) in all these patients.

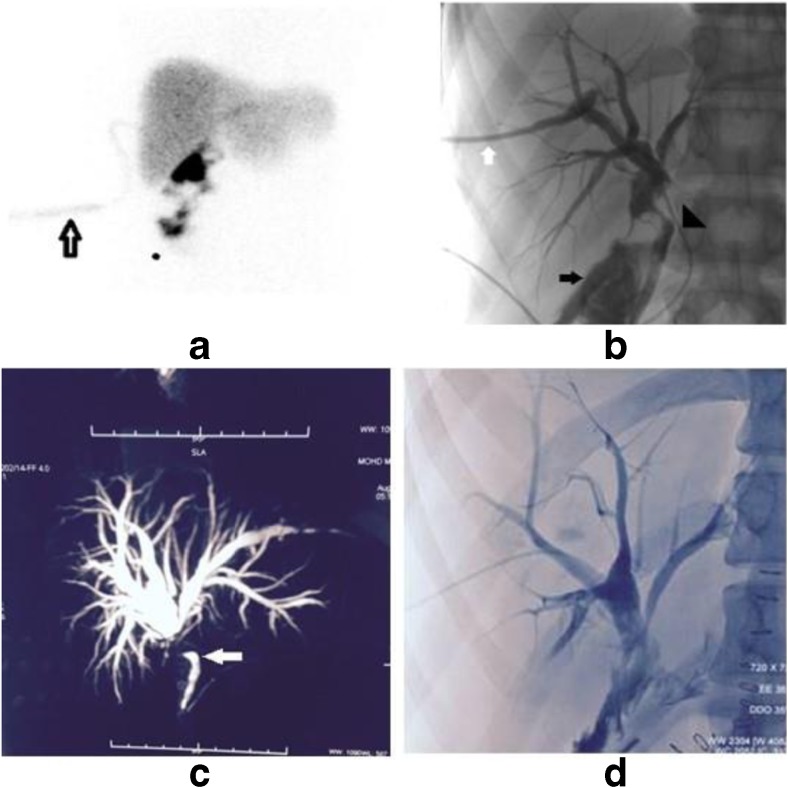

Fig. 2.

a Percutaneous cholangiogram shows a leak at the CBD level with contrast in the surgical drain (white arrow). b Percutaneous cholangiogram shows no leak and no residual stricture. Note that no contrast is seen in the surgical drain

Fig. 3.

Bile leak from CHD injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a 17-year-old male. a SPECT planar images show tracer stasis and tracking (black arrow) suggestive of active bile leak. b PTC shows pig tail drain placed in the right hepatic duct (white arrow) with active leak of contrast (black arrow) and infant feeding tube placed in CHD (black arrowhead). c MRCP 4 months after PTBD shows healed CHD stricture and CBD (white arrow). d PTC following hepaticojejunostomy shows a widely patent anastomotic site

Table 1.

Patient outcome post-PTBDs

| No. | Indications | No. of PTBDs |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Surgical reconstruction | 89 |

| 2 | Leak healed without residual stricture | 44 |

| 3 | Leak healed with residual stricture for which balloon dilatation was done | 18 |

| 4 | Sepsis and death | 06 |

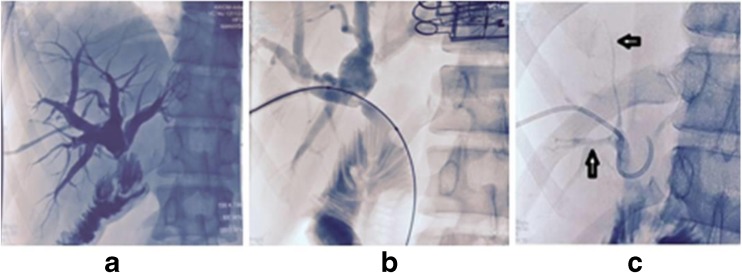

Fig. 4.

Previously shown case 6 months later presented with a stricture at the hepaticojejunostomy anastomotic site which was managed with balloon stricturoplasty and pig tail placement. a Percutaneous cholangiogram shows a sharp cutoff of the common hepatic duct at the anastomotic site suggestive of an anastomotic site stricture. b Cholangiogram shows stricturoplasty of the tract with compliant balloon. c Follow-up cholangiogram after 6 weeks shows no residual stricture at the anastomotic site. Note the decompress biliary system (black arrow)

Discussion

The main causes of biliary leak are bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy [2, 3], hepaticojejunal anastomosis [5], common bile duct-to-common bile duct anastomosis associated with liver transplantation [3], and hepatic lobectomy [3, 6].

Endoscopic Intervention

Therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has been advocated widely in small biliary leaks as an alternative to surgery [2–4, 6]. When endoscopic insertion of a stent can be achieved, a definitive closure of the leak is attained with a frequency ranging from 75 % [2] to 100 % [7, 8]. However, the intubation of the common bile duct above the leak is sometimes difficult and a technical failure rate of 46 % has been reported [2]. Furthermore, ERCP is not possible in patients with hepaticojejunal anastomosis.

Surgical Intervention

Injuries that cannot be definitively treated with percutaneous or endoscopic techniques require surgical repair. These include large lateral defects in major ducts, strictures refractory to percutaneous or endoscopic treatment, and nearly all complete transections and ligations.

However, for successful surgical reconstruction, it was found that eradication of intraabdominal infection (i.e., drainage of all fluid collections) completes the preoperative characterization of the bile duct injury with cholangiography and preoperative diversion of the bile is essential.

Depending on the cause of the leak, early intervention is favored by many surgeons and definitive surgical repair is attempted [1]. Hepaticojejunal anastomosis is another procedure commonly used to treat biliary leaks. At a later stage of the disease, surgical re-exploration is often difficult because of infection, edema, and scarring in the periportal area [2, 4, 6]. Furthermore, when the leak involves the intrahepatic ducts, hepatic lobectomy is sometimes required [9].

Percutaneous Interventions

Biloma Drainage

Most bilomas can be drained percutaneously using a combination of US and CT for imaging guidance [2]. Because the symptoms of bile collections in the abdomen are often subtle, diagnosis and treatment are frequently delayed [10]. Fluid collections that are known or suspected to contain bile should be drained promptly; delayed drainage is associated with an increased incidence of serious complications, such as abscess formation, cholangitis, and sepsis [10].

Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage Placement

Complete ductal ligation or transection, proximal duct injury, and transection or ligation of an aberrant right hepatic bile duct usually require percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) with percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) placement for biliary decompression, diversion, or both [2–4, 6, 11]. In patients with cholangitis, excessive manipulation of catheters in the bile ducts should be avoided to reduce the risk of sepsis. In these patients, an external drain may be placed for 2–4 days to allow decompression and a course of antibiotic therapy to be administered before internal catheter placement is attempted [12]. In patients without cholangitis, placement of an internal-external catheter may be possible from the start [12]. In patients with injuries that preclude the passage of a catheter into the duct (e.g., complete ligation of the common duct), an external drainage catheter positioned immediately proximal to the level of ductal obstruction provides a palpable landmark for the surgeon when the site is obscured by scar tissue [12].

Injuries of the common duct usually require the placement of only one drain, whereas hilar injuries with high-grade strictures of the left and right hepatic ducts or loss of continuity in the ducts require bilateral drain placement [12, 13]. Transection or ligation of an aberrant right hepatic duct requires targeted drain placement in the affected segments of the biliary tree [12–14].

Bile leaks from small peripheral ducts can be definitively treated with a combination of percutaneous biloma drainage and either PTBD placement or endoscopic common duct stent placement to divert bile flow away from the leakage site [12]. It should be noted that the percutaneous biliary drainage procedure especially in an undilated system is technically challenging, requiring expertise limiting its widespread availability.

Guido Cozzi et al. [15] in their study successfully treated post-surgical biliary leak in 15 of 17 patients (88 %) following PTBD. No major complications occurred after drainage in their study.

Our results confirm the efficacy of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage alone in the treatment of small biliary leaks because 62 of 157 patients were completely cured. Leaks healed without any residual stenosis in most patients, while a slight bile duct narrowing at the site of the defect in the bile duct wall occurred in 18 patients which could also be effectively tackled by less invasive balloon dilatation. Eighty-nine patients underwent surgical reconstruction post-biliary drainage.

These results suggest that the use of a relatively large drainage catheter (8–10 Fr), and drainage for at least 3–4 weeks might prevent secondary stenosis of the bile duct after healing of the leak in most cases. However, a residual narrowing of the bile duct can be treated easily and successfully through the percutaneous route before withdrawal of the drainage catheter.

In conclusion, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage has been proven to be an important technique in the management of post-surgical biliary leaks. We found that PTC and biliary drainage can be performed with high technical success and low complication rates in patients with post-surgical biliary leaks. PTBD is a feasible, effective, and safe procedure for the treatment of post-surgical biliary leaks. It is therefore a reliable alternative to surgically repair smaller leaks, and in patients with larger defects, it helps prepare the patients preoperatively for surgical reconstruction.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Czerniak A, Thompson JN, Soreide O, Benjamin IS, Blumgart LH. The management of fistulas of the biliary tract after injury to the bile duct during cholecystectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1988;167:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liguory C, Vitale GC, Lefebre JF, Bonnel D, Cornud F. Endoscopic treatment of postoperative biliary fistulae. Surgery. 1991;110:779–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherman S, Shaked A, Cryer HM, Goldstein LI, Busuttil RW. Endoscopic management of biliary fistulas complicating liver transplantation and other hepatobiliary operations. Ann Surg. 1993;218:167–175. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199308000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith AC, Schapiro RH, Kelsey PB, Warshaw AL. Successful treatment of nonhealing biliary-cutaneous fistulas with biliary stents. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:764–769. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)91136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaccaro JP, Dorfman GS, Lambiase RE. Treatment of biliary leaks and fistulae by simultaneous percutaneous drainage and diversion. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1991;14:109–112. doi: 10.1007/BF02577706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufman SL, Kadir S, Mitchell SE, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage for bile leaks and fistulas. AJR. 1985;144:1055–1058. doi: 10.2214/ajr.144.5.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldin E, Katz E, Wengrower D, et al. Treatment of fistulas of the biliary tract by endoscopic insertion of endoprostheses. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:418–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman BJ, Cunningham JT, Marsh WH. Endoscopic management of biliary fistulas with small caliber stents. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:705–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branum G, Schmitt C, Baillie J, et al. Management of major biliary complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1993;217:532–541. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199305010-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CM, Stewart L, Way LW. Postcholecystectomy abdominal bile collections. Arch Surg. 2000;135(5):538–542. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.5.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuidema GD, Cameron JL, Sitzmann JV, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic management of complex biliary problems. Ann Surg. 1983;197:584–593. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198305000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saad N, Darcy MD. Iatrogenic bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;11(2):102–110. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Covey AM, Brown KT. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;11(1):14–20. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perini RF, Uflacker R, Cunningham JT, Selby JB, Adams D. Isolated right segmental hepatic duct injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;28(2):185–195. doi: 10.1007/s00270-004-2678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cozzi G, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage in the management of postsurgical biliary leaks in patients with nondilated intrahepatic bile ducts. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29:380–388. doi: 10.1007/s00270-005-0102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]