Abstract

Since the initial description of tropical pyomyositis 130 years ago, this disease continues to retain some mystery for physicians and surgeons. The infrequency, variable epidemiologic and demographic profile, diagnostic dilemmas and limited literature continue to make it an enigma with limited understanding. In the span of nearly 130 years, worldwide English literature search has revealed an average of only two to three reported cases every year globally. We recently managed a case of tropical pyomyositis which posed a clinical and radiologic diagnostic dilemma. The rarity of disease and published literature prompted us to garner demographic and disease characteristics data from historical review of two Pan-Indian journals, with the aim of aiding management. Data has been screened since 1950 from the Medical Journal Armed Forces India (MJAFI) and the Indian Journal of Surgery (IJS), which report cases from different geographical conditions and ethnicity all over the nation. We found only six case reports in the MJAFI, while there was surprisingly no publication regarding pyomyositis in the IJS. We present a case report of a 39-year-old male who developed pyomyositis of the left calf muscle and review published data from these journals over the last 65 years.

Keywords: Pyomyositis, Calf muscle, Indian Journal of Surgery, Medical Journal Armed Forces India

Introduction

Tropical pyomyositis was first described by Scribia in 1885 [1]. It was initially considered a tropical endemic disease and characterized by formation of microabscesses in striated muscle. Since then, this disease has remained an international rarity with scattered publications across the globe. It is defined as acute intramuscular suppurative bacterial infection due to haematogenous spread of microorganism, commonly Staphylococcus aureus (90 %) [2–4]. This disease is often misdiagnosed due to non-specific symptoms and signs, clinical dilemmas due to diverse differential diagnosis and absence of clear-cut guidelines. Traditionally believed to be a disease prevalent in tropical regions and usually affecting young children, it is now seen to affect immunocompromised hosts or those suffering from chronic ailments in temperate countries too. However, it is interesting to see that healthy recruits and soldiers who undergo regular physical training are frequently affected by tropical pyomyositis (TP). Current clinical disease and patient profiles also raise questions about accepted predisposing factors in acquiring pyomyositis. We recently managed a case of TP, which despite the availability of multiple diagnostic modalities, was referred with doubtful diagnosis which was further confounded by ultrasound findings. This prompted us to attempt identification of typical patient and disease profiles through retrospective literature search and identify any changes in the same.

We evaluated data through physical and electronic search of two major journals of our country, namely the Medical Journal Armed Forces India (MJAFI) and the Indian Journal of Surgery (IJS) since 1950. Both are Pan-Indian journals publishing research across geographical regions and the nation with a publication history of over 50 years. While the MJAFI deals predominantly with service personnel and dependants, the IJS has a dominant civil population-based research. Evaluation to correlate the common factors of our case with other reported cases from these journals was done in an attempt to arrive at possible guidelines in diagnosing and managing this entity. Out of six cases reported in the MJAFI since 1950, three were soldiers ranging in age from 18 to 30 years, the remaining being from the pediatric age group. We could not find any case report on pyomyositis published in the IJS since 1950.

Though findings cannot be truly extrapolated, a better understanding of this enigmatic disease can be expected.

Case Report

A 39-year-old previously healthy soldier with no co-morbidities presented to a peripheral hospital with complaints of insidious onset, gradually progressive pain in his left calf of 2-week duration. It was accompanied with diffuse swelling of his calf, and he was unable to walk since the 3-day duration. Pain was associated with fever and anorexia, but the patient denied any specific history of sustaining trauma in any form. He was performing routine duties with exercise and games till the onset of symptoms. Despite conservative management and rest, he exhibited worsening of symptoms and was unable to bear weight on the affected limb. He was thereafter referred to our centre for management. Clinically, there was diffuse swelling over the lateral aspect of upper one third of the left leg with tenderness but no obvious rise of temperature. There was no evidence of cellulitis, lymphangitis or inguinal lymphadenopathy. There was no clinical evidence of fluctuation or any skin changes, but the underlying compartment felt firm. No distal neurovascular deficit was noted, and there was no clinical evidence of raised intracompartment pressure. Lab investigations revealed leukocytosis (TLC 18,000) with renal, hepatic and coagulation parameters being normal. Blood sugar profile was normal with no evidence of diabetes. Viral markers including HBsAg, anti-HCV antibody (Ab) and anti-HIV Ab were also negative. Diagnosis considered was an infected haematoma, and though rare, considering features of a deep-seated abscess, the diagnosis of pyomyositis was also entertained. The patient was empirically started on injection of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 1.2 gm IV every 8 h. A plain radiograph of the leg did not reveal any obvious swelling or gas in subcutaneous or myofascial planes. Blood culture was send and reported as sterile. It was decided to proceed with an ultrasound-guided aspiration. The ultrasound displayed features suggestive of a soft tissue sarcoma. This led us to reconsideration of approach, and we refrained from doing an aspiration/exploration. Contrast-enhanced MR examination was performed which revealed bulky and edematous muscles of the posterior compartment of the left leg characterized by hyperintense signal on T2-weighted (T2W) and short tau inversion recovery (STIR) images (Fig. 1a, b). Post-contrast images revealed heterogeneous enhancement in the affected muscles and multiloculated collections with peripheral rim enhancement in the muscles of the deep posterior compartment (Fig. 2a, b). The soleus, tibialis posterior and peroneus longus were predominantly involved. On the basis of MRI features of pyomyositis, injection of amoxiclav was discontinued and injection of cloxacillin 1 gm IV every 6 h was commenced. During this period, the patient started developing features of compartment syndrome with worsening symptoms and pain on passive dorsiflexion. No neurovascular deficit was observed. He was operated and underwent two-incision, four-quadrant fasciotomy of the left leg with abscess drainage. Intraoperatively, 15–30 ml of intramuscular pus was drained from the lateral and posterior compartment muscles of the leg while no intermuscular fluid collection was noted. Remaining muscles were swollen, friable and inflamed. He made a rapid recovery and was able to bear weight from the third postoperative day. Postoperatively, the patient was continued on injection of cloxacillin, while injection of gentamicin 80 mg IV every 8 h and injection of metronidazole 500 mg IV every 8 h were added. The pus culture was reported as no growth. Following rapid recovery, the antibiotics were discontinued after 5 days. Within 2 weeks, he was performing all routine activities without discomfort. The fasciotomy wounds were closed primarily after 2 weeks, employing skin approximators.

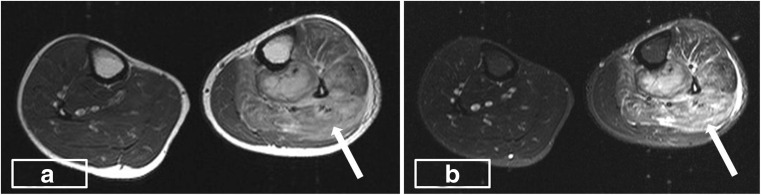

Fig. 1.

a, b Axial T2W and STIR images showing an increase in the bulk and hyperintense signal in the muscles (arrow) of the anterior and posterior compartment of the left leg

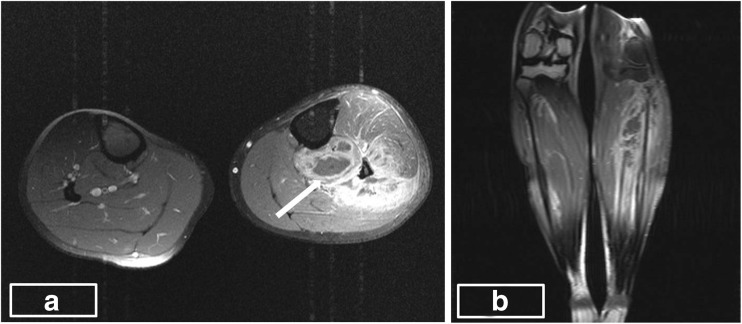

Fig. 2.

a, b Post-contrast axial and coronal images showing heterogeneous enhancement of the affected muscles and multiple focal collections with peripheral enhancement in the muscles of the deep posterior compartment (arrow)

Discussion

Pyomyositis is defined as an acute intramuscular bacterial infection that is secondary to haematogenous spread of a microorganism, usually S. aureus, into a skeletal muscle and is neither a result of infection of the adjacent skin, soft tissue or bone nor due to penetrating trauma. Original descriptions and prevalence relate to the involvement of healthy children and adults from tropical regions. Literature over last few decades has revealed an increasing number of cases of pyomyositis in immunocompromised adults or associated with chronic disease reported from temperate regions [5]. World literature search reveals that pyomyositis has been traditionally described as affecting a single muscle group, especially in deep compartments of the thigh, hip and pelvis [3]. Though Bickels et al. noted quadriceps (26 %) involvement as the most common, followed by iliopsoas (14 %), literature is replete with diverse presentations across different muscle groups, with Unnikrishnan describing involvement of the obturator internus as commonest [6]. In our case, calf muscles were involved which is relatively a less common presentation. Evidently, the patient and disease profiles seem to be undergoing changes. Predisposing factors mentioned in the literature are immunodeficiency, malnutrition, cancer, viral infection, IV drug abuse and hepatitis B carrier state and are seen in the temperate regions [1–3]. In tropical climates, aetiological predisposing factors and pathogenesis need to be evaluated among healthy young immunocompetent individuals who manifest the disease. Muscle exertion and innocuous trauma can be predisposing factors and need detailed consideration in studies. Reports suggest that physical exertion in healthy males who have evidence of Staphylococcus skin infection may be predisposed to polymyositis. The pathogenesis of pyomyositis is thought to involve two distinct but coincident events: muscle injury, either acute or due to overuse, giving rise to a subclinical intramuscular haematoma, and bacteraemia occurring within a few days of the muscle trauma and presumably seeding the haematoma with organisms. Even insect bites have been implicated in predisposing to bacteraemia and leading to pyomyositis in injured muscles [7]. This may explain the higher tropical incidence. It is postulated that un-injured skeletal muscle is intrinsically resistant to infection because myoglobin binds to iron avidly, which is necessary for growth of the organism, but when muscle trauma is present, there is sequestration of elemental iron [8], which is necessary for bacterial growth. Other factors implicated but not proven include general debility, toxins, impaired host defenses and coxsackie group of viruses. Since there is a slight increase in incidence during the rainy season, viruses have also been considered to be the primary aetiological agents [9]. Cases reported by physicians also describe proximal muscle weakness or myopathy and patients often administered steroids during evaluation [5]. With diabetes and immunosuppression in solid organ transplant patients cited as predisposing features, there is further need to identify bacterial pyomyositis from other myopathies for correct and timely treatment.

Disease progression is described in three phases. The first phase is invasive and occurs during the first 2–3 weeks, during which a diagnosis is often difficult. Pain and fever are usually accompanied with mild swelling or myalgia. Palpation may be tender with a wooden consistency, while aspiration does not yield pus. Field conditions may pose diagnostic problems in soldiers [2, 3]. Usually, the disease progresses to second suppurative phase during which high-grade fever, chills, myalgia and local tenderness become evident. Our patient was also diagnosed at second stage at a tertiary centre, due to a lack of clinical suspicion and diagnostic aids in field conditions. Finally, if untreated at second stage, the third stage of systemic sepsis may be overwhelming [4, 10, 11].

Clinical features common among all case reports evaluated in the screened literature including our case were fever and myalgia with high association with raised leukocyte counts (Table 1). However, these cannot be taken as unique or a marker for identification since sensitivity and specificity are low. Blood culture is positive in 5–30 % of cases, which remained negative in our case. Up to 75 % of culture positivity is reported for Staphylococcus, while Gram-negative bacilli are also increasingly isolated [12]. Comparing the common factors among case reports (total of six) published in the MJAFI and IJS since 1950, fever was present in all patients. One patient had normal leukocyte count, and two patients did not have culture positive S. aureus. There is significant variability in the muscle groups involved, varying from the lower extremity (distal or proximal) to the upper extremity (truncal or generalized). Patient factors like location of trauma, extent of bacteraemia and possibly the degree of immunosuppression may be responsible for the extreme variability. Among investigation modalities, USG can be done as an initial test which shows hypoechoic areas and bulky muscles. Overlapping features like a differential diagnosis of sarcoma as in our patient can confuse and delay the diagnosis. Osteomyelitis, muscle infarction, synovitis, infected haematomas and other ailments add to confounding the diagnosis. MRI forms the current gold standard for diagnosis and shows hyperintensity on T1W and enhancement on gadolinium [2, 3]. Contrast-enhanced MR examination was performed which revealed bulky and edematous muscles of the anterior and posterior compartment of the left leg characterized by hyperintense signal on T2W and STIR images (Fig. 1a, b). Post-contrast images revealed heterogeneous enhancement in the affected muscles and multiloculated collections with peripheral rim enhancement in the muscles of the deep posterior compartment (Fig. 2a, b).

Table 1.

All published cases of tropical pyomyositis in the MJAFI and IJS since 1950

| No. of patients (n = 6) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| <12 | 3 |

| >12 | 3 |

| Geographical location in India | |

| North | 2 |

| South | 1 |

| North-west/north-east | 3 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 5 |

| Female | 1 |

| Fever (>100 °C) | |

| Yes | 6 |

| No | 0 |

| Leukocytosis (>11,000) | |

| Yes | 5 |

| No | 1 |

| Blood C/S (Staphylococcus aureus) | |

| Yes | 4 |

| No | 2 |

Pyomyositis unfortunately prevails in geographical areas where MRI is unavailable or limited. Gallium scan is extremely sensitive in diagnosing occult abscess but is limited due to high cost [10]. Muscle biopsy in our patient showed necrosis and haemorrhage between muscle fibers which is similar to that in the reported literature [2, 10]. Stage I TP was claimed to be treated successfully with oral antibiotics such as cloxacillin [11]. With changes in bacterial sensitivity, regimens are undergoing regular change. Stage II requires intravenous antibiotics and abscess drainage either by image-guided aspiration or surgery [7]. Stage III pyomyositis requires multimodality treatment as per sepsis guidelines.

Literature search shows that up to 20–50 % of cases have a history of blunt trauma to muscles [2, 3]. Considering higher reports in the service journal, it may be an important predisposing factor. Though some service case reports deny an obvious history of trauma to patients, including our own case, the highly physical nature of soldiering activities may be relevant. Five of the reported patients had a history of physical exertion rather than specific trauma, while one followed a gluteal abscess. Other aetiological factors related to the demography of disease are malnutrition and viral infection [7]. Malnutrition was not evident in either our case or earlier published reports from the MJAFI. Apart from the commonest implicated Staphylococcus, other organisms isolated are group A streptococcus (1–5 %), Hemophilus and Gram-negative bacilli [12].

Failure to have a high degree of suspicion, lack of early diagnosis and delayed or incomplete surgical treatment can lead to muscle scarring, residual weakness and mortality of up to 0.5–2.5 % [2, 13]. Tropical/temperate pyomyositis is a rare, enigmatic and evolving ailment. The variability and rarity of cases, along with changing patient and bacteriologic profile, also needs to be re-evaluated. Disease profiles may also undergo changes over time. A detailed assessment of six published reports over 130 years in two Pan-Indian journals did not yield specific features to aid diagnosis. Though trauma and a source of sepsis in a healthy young male are likely to be the most critical features, the pathogenesis would need further research. A high index of suspicion and low threshold for MRI would possibly increase the yield of stage I disease and help in identifying characteristics for better and early management.

Despite evaluating factors in all published case reports, we could not arrive at specific conclusions on factors predisposing to this disease. An extreme paucity of cases and literature also precluded us from identifying early or typical features. Though we found the calf tense on examination, compartment pressure was not recorded. This may yield early information and lower the threshold for surgery. Currently, further evaluation across multiple case reports, series and studies need to be conducted to reveal the mystery of this disease.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Chauhan S, Jain S, Varma S, Chauhan SS. Tropical pyomyositis (myositis tropicans): current perspective. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:267–270. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2003.009274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bharathi RS, Suryanarayan N, Seth N. Primary obturator internus pyomyositis: a case report. Med J Armed Forces India. 2011;67:362–363. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(11)60095-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prasad AN, Majumdar D, Puar NS. Tropical pyomyositis: rare presentation: a case report. Med J Armed Forces India. 2006;62:387–388. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(06)80119-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell LA, Rooks VJ, Martin JE, Burgos RM. Paraspinal tropical pyomyositis and epidural abscess presenting with low back ache. Radiol Case Rep (online) 2009;4:303. doi: 10.2484/rcr.v4i3.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chauhan S, Kumar R, Singh KK, Chauhan SS. Tropical pyomyositis: a diagnostic dilemma. JIACM. 2004;5(1):52–54. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unnikrishnan PN, Perry DC, George H, Bassi R, Bruce CE. Tropical primary pyomyositis in children of the UK: an emerging medical challenge. Int Orthop. 2010;34:109–113. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0765-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamer K, Hall M, Moharam A, Sharr M, Walczak J. Gluteal pyomyositis in a non tropical region as a rare cause of sciatic nerve compression: a case report. JMRC. 2008;2:204. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grandson WR, Ekysyn SJ, Philips I. Staphylococcus bacteremia 400 episodes. BMJ. 1984;288:300–305. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6413.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh SB, Singh VP, Gupta S, Gupta RM. Tropical myositis; a clinical, immunological and histopathological study. J Assoc Physc India. 1989;37:561–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarma YS, Chatterjee M, Tiwari GL, Kathuria SK, Gupta A. Tropical pyomyositis with staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Med J Armed Forces India. 2004;60:302–304. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(04)80073-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson DP, Soares S, Kanade SV (2011) Community acquired MRSA pyomyositis: case report and review of literature. Journal of Tropical medicine, Article ID 970848, 4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Chattopadhyay B, Mukhopadhyay M, Chatterjee A, Biswas PK, Chatterjee N, Debnath NB. Tropical pyomyositis. North Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:600–603. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.120796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashemi SA, Vosoughi AR, Pourmokhtari M. Hip abductors pyomyositis: a case report and review of the literature. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012;6(2):184–187. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]