Abstract

Preputial calculi are the rarest form of urolithiasis seen usually in an uncircumcised male with phimosis. We report a case in an elderly male who presented with azotaemia. Calculi are evident on clinical examination by palpation. Late presentation by the patient leads to complications. Treatment is by dorsal slit or circumcision. The case highlights the need of early recognition and treatment of this rare condition to prevent any complication.

Keywords: Preputial calculi, Phimosis, Dorsal slit, Circumcision

Introduction

Preputial calculi are extremely rare manifestation of urolithiasis with only 11 cases reported so far in the literature. They are the result of poor hygiene, where in the inspissated smegma acts as nidus for stone formation and the phimosis adds to it by stasis. Most of these cases are in adults and elderly. We report a case of preputial calculi with azotaemia in an elderly male, circumcision in whom delivered 25 calculi.

Case History

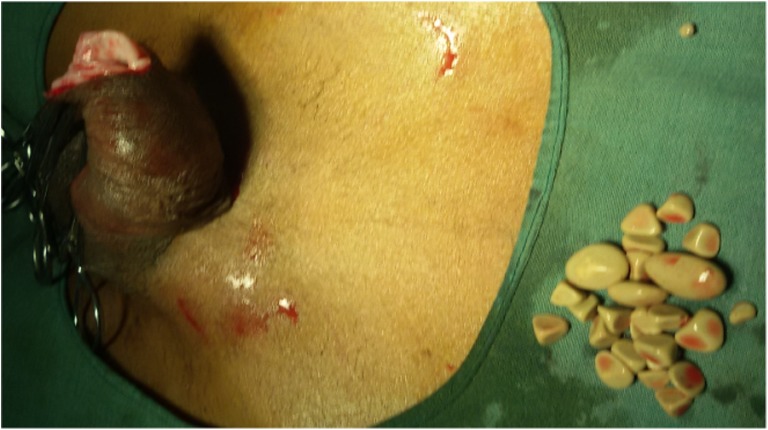

A 65-year-old man presented to our outpatient department with a mass at the tip of the penis with poor flow of urine since 6 months. Physical examination revealed phimosis (Fig. 1). The foreskin was felt separately from glans as a bag containing multiple calculi. Surprisingly, there was no urinary retention; however, his serum creatinine was 2.4 mg%. Abdominal sonography showed a stag horn calculus in the right kidney as well. His urinary as well as serum calcium was within normal limits. Patient underwent circumcision, which revealed 25 grayish white faceted calculi, largest measuring 1.5 cm and the smallest measuring 4 mm (Fig. 2). Calculi were made up of calcium phosphate as found on stone analysis. Subpreputial culture grew Escherichia coli organisms. Patient’s renal functions were normalized post surgery, and the patient is being evaluated for the management of right-sided stag horn calculus.

Fig. 1.

Phimosis on examination

Fig. 2.

Calculi after extraction by circumcision

Discussion

Preputial calculi are so rare that one hardly sees a case in his/her life time during day-to-day practice. The literature search could find only 11 cases that are reported till today, and the comparison of these cases with our case is shown in tabular form in Table 1. Almost all the cases occur in uncircumcised males and the phimosis is the common presentation. Though they can occur in any age, most of the cases are reported in adults and elderly [1].

Table 1.

Comparison of our case with the cases reported so far

| Literature | Age of the patient | Causative factor | Associated conditions | Composition of calculi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our study | 65 years | Phimosis | Obstructive uropathy | Calcium phosphate |

| Ellis DJ et al. [1] (1986) | 4 years | Post epispadias repair, foreign body induced calculus | Normal renal function with normal upper tracts | Ammonium acid urate, magnesium ammonium phosphate hexahydrate |

| Yuasa et al. [2] (2001) | 92 years | Phimosis | Obstructive uropathy | NA |

| Tuğlu D et al. [3] (2013) | 12 years | Phimosis | Normal renal function with normal upper tracts with associated preputial fistula and paraplegia | NA |

| Mohapatra TP et al. [4] (1989) |

65 years | Phimosis | Normal renal function with normal upper tracts with associated penile malignancy | Calcium ammonium magnesium phosphate, Magnesium calcium urate |

| Kim SO et al. [5] (1983) |

NA | Phimosis | Associated with bladder calculi and TCC of bladder | NA |

| Spataru RI et al. [6] (2015) |

5 years | Phimosis | Normal renal function with normal upper tracts associated with paraparesis | Calcium oxalate |

| Sharma SK et al. [7] (1977) |

NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wilford EC [8] (1925) | Adult farmer | Phimosis | Post circumcision, epithelioma developed | Sodium and calcium phosphate |

| Shahi UN et al. [9] (1962) |

55 and 60 years (2 cases) |

Phimosis | Came with retention of urine | Calcium, magnesium, phosphate and carbonate |

| Nagata D et al. [10] (1999) |

32 years | Phimosis | Had associated bladder calculi | Magnesium ammonium phosphate, calcium phosphate, calcium carbonate |

| Sharma SK [11] (1983) |

NA | Phimosis | NA | NA |

NA not available

The symptoms and the findings are due to phimosis in these patients, which causes urinary stasis beneath the foreskin. In some cases, the obstruction may be so severe as to result in obstructive uropathy as in our case [2]. Less severe cases may manifest as strangury, poor flow, prolonged voiding time, haematuria, and foul smelling discharge from prepuce. Inguinal lymphadenopathy may result as a result of inflammatory process in case of severe infection [3]. Calculi are often palpable on examination; however, radiograph can confirm the same.

Evaluation of the rest of the urinary tract helps to unearth any other abnormality as seen in our case. Metabolic evaluation can provide clues to the causation of calculi especially in a situation wherein the calculi are found in the other parts of urinary tract other than the prepuce. Other than the raised serum creatinine, all other biochemical parameters of serum as well as urine were normal in our case. There are chances of calculi originating in the kidney, ureter and urinary bladder getting trapped while passing through the phimotic preputial sac. But in our case, the renal calculus was of staghorn variety, which in most of the cases is of infective origin and the long standing phimosis might have a role in keeping the urine infected and thus responsible for the causation of renal calculus as well. Though the condition is diagnosed before any major complications occur, there are reports of a fistula as a complication of preputial calculi [3] as well as case of coexisting penile malignancy with preputial calculi [4].

Preputial calculi arise from three possible mechanisms, as characterized by Winsbury-White, namely, (1) inspissated smegma, (2) combination of smegma and urinary salts and (3) concentration of urinary salts alone. Wilford has characterized them according to their pathogenesis: (1) inspissated smegma with lime salts, (2) struvite composition secondary to infection and (3) stones formed in the proximal urinary tract, which are trapped during migration. Stone analyses often reveal calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate and in few cases, triple phosphate as well. Culture of the subpreputial space most often reveals infection with E, coli [1, 3].

Treatment of the condition is usually by dorsal slit and circumcision, by which the calculi are extracted and the causative pathology is removed. The recurrence is unlikely in cases of properly performed circumcision. Usually, it suffices to relieve the obstructive uropathy as well except in cases where there are other associated causes such as calculi higher up in the urinary tract [5]. Treatment should be directed to the metabolic abnormality when such an abnormality is found on evaluation.

Conclusion

Preputial calculi, though a rare entity, can be a cause of obstructive uropathy in uncircumcised males with poor hygiene, proper treatment of which by circumcision alleviates the symptoms as well as the disease.

References

- 1.Ellis DJ, Siegel AL, Elder JS, Ducket JW. Preputial calculus: a case report. J Urol. 1986;136:464–465. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)44910-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuasa T, Kageyama S, Yoshiki T, Okada Y. Preputial calculi: a case report. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2001;47(7):513–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuğlu D, Yuvanç E, Yılmaz E, Batislam E, Gürer YK. Unknown complication of preputial calculi: preputial skin fistula. Int Urol Nephrol. 2013;45(5):1253–1255. doi: 10.1007/s11255-013-0496-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohapatra TP, Kumar S. Concurrent preputial calculi and penile carcinoma—a rare association. Postgrad Med J. 1989;65(762):256–257. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.65.762.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SO, Juag GD, Jang CS, Paick JS, Lee MS. Preputial calculi associated with urethral calculi, bladder calculi and bladder transitional cell carcinoma: a case report. Korean J Urol. 1983;24(3):487–490. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spataru RI, Iozsa DA, Ivanov M. Preputial calculus in a neurologically impaired child. Indian Paediatr. 2015;52:149–150. doi: 10.1007/s13312-015-0591-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma SK, Bapna BC. Preputial calculi. Int Surg. 1977;62:553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilford EC. Remarkable preputial calculus. Chin Med J. 1925;39:712. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shahi UN, Ram I. Preputial calculi. Br Med J. 1962;1(5294):1738–1739. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5294.1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagata D, Sasaki S, Umemoto Y, Kohri K. Preputial calculi. BJU Int. 1999;83(9):1076–1077. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma SK. Phimosis and the preputial calculus. Indian Pediatr. 1983;20(5):386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]