Abstract

Gastric teratoma is a very rare tumor, accounting for less than 1 % of all teratomas in infants and children. Melena or upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding in newborns and infants is a rare event and is usually caused by a benign lesion. Gastric teratoma has been reported as a cause of gastrointestinal bleeding on a few occasions. As gastric teratomas generally present as a palpable abdominal mass, more aggressive solid masses of childhood must be excluded. We present intramural extension of gastric teratoma presented as symptom of gastric outlet obstruction and melena.

Keywords: Stomach, Teratoma, Gastric

Introduction

Benign gastric tumors are rare in children and include hyperplasic and adenomatous polyp, leiomyoma, and lipoma. Teratomas are embryonal neoplasms that contain tissues from all the three germ layers. These lesions frequently present in infancy and childhood and may be benign or malignant and cystic or solid [1]. They can occur anywhere, the common sites being the sacrococcygeal region, the retroperitoneum, and the gonads. Gastric teratomas are rare benign tumors and account for less than 1 % of teratomas [1]. The disease usually occurs in children younger than 1 year of age especially neonates; however, there are reports of this tumor in older children [2]. To date, less than 100 cases have been reported in literature [3]. This report describes a 3-month-old boy who presented with recurrent vomiting and melena.

Case report

A 3-month-old boy was admitted for recurrent blood stained vomiting and melena since 1 month. Ten days before, his mother noticed a vague lump palpable in left upper abdomen. There was no history of fever, jaundice, and loss of appetite. The past history was not significant. On general examination child was anemic and dehydrated. On abdominal examination there was fullness in left upper abdomen and on palpation there was approximately 8 × 8 × 10 cm mass was present in left hypochondrium and umbilical region. The lump was slightly moved with respiration and firm in consistency. The rest of the abdomen was within normal limits. CT revealed a large heterogenous mass from the posterior wall of the stomach with a nodular projection in the stomach [Fig. 1]. The bowel loops were displaced downwards and to the right and the left kidney was displaced inferiorly. After correction of hemoglobin, hydration, and electrolyte, a laparotomy was performed and a relatively large mass of 8 × 8 × 10 cm was found on the greater curvature of stomach [Fig. 2] with intraluminal extension with predominantly extra luminal growth [Fig. 3]. The rest of the abdominal organs were normal. The tumor was fully excised and the stomach was repaired by vicryl 3-0 suture. Microscopic examination revealed gastric tissue with an intramural neoplasm. The lining epithelium was intact and the neoplasm was composed of mature cartilage, lymphoid, respiratory, and nerve tissue which was compatible with teratoma. The post-operative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged in good general condition. Regular follow-ups over a 6-month period revealed no evidence of tumor relapse.

Fig. 1.

Heterogenous mass from the posterior wall of the stomach with a nodular projection in the stomach

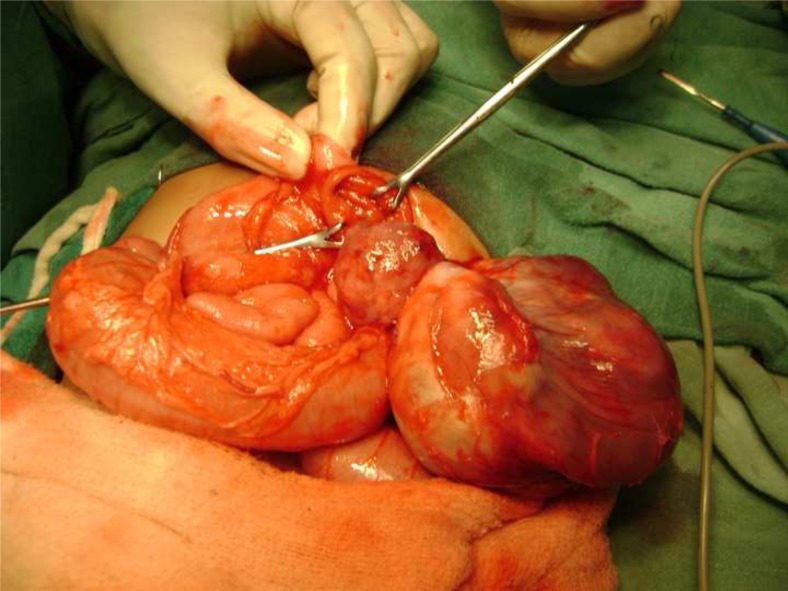

Fig. 2.

Mass of 8 × 8 × 10 cm found on the greater curvature of stomach

Fig. 3.

Mass with intraluminal extension with predominantly extra luminal growth

Discussion

In children, teratomas occur most commonly in the sacrococcygeal region (60–65 %). Other sites of origin are the mediastinum (11.7 %), gonads (10–20 %), presacral region (5 %), and retroperitoneal, intracranial, and cervical regions (<5 %) [4]. Gastric teratomas account for less than 1 % of teratomas in children and are even rarer in adults. Gastric teratomas are not associated with the dorsal body axis, embryonic body wall, and somatic pleura [5]. They differ from teratomas arising from other sites in three ways. Firstly, they are not associated with any congenital anomalies in contrast to 10–15 % incidence at other sites. Secondly, most of the gastric teratomas (>95 %) are seen in males [6] compared to female preponderance (65–70 %) at other sites. Lastly, they are almost always benign in nature as compared to 10–39 % incidence of malignancy at other sites such as the sacro-coccygeal region, mediastinum, and gonads [2]. As a result, they have an excellent prognosis after surgery, compared to teratoma of other site. Gastric teratomas are seen mainly in infants and children. The commonest presenting features are abdomen distension and mass, the other presentations being vomiting, feeding problems, respiratory distress, weakness, abdominal pain, and constipation. Hemetemesis and melena are extremely rare symptoms, seen in patients who have tumors with an endophytic component [7]. Plain radiographs of gastric teratomas usually show a soft tissue mass with calcification in the upper abdomen. Calcifications are seen in more than 50 % of patients [7]. Presence of bone and teeth is considered pathognomonic. Barium meal studies demonstrate gastric deformities or extrinsic pressure on bowel loops. Intra luminal filling defect is characteristic of gastric teratomas [8]. The sonographic appearances vary from a predominantly cystic mass to a heterogenous mass with solid and cystic areas. The solid areas are heterogenous and may show focal areas of hyperechogenicity with distal shadowing suggestive of calcification [9]. CT is a well evaluation for gastric teratoma. On histopathological examination, the tumors demonstrate several tissues derived from all the three germ layers—skin and its appendages, smooth muscle, fat tissue, cartilage, respiratory epithelium, and neural tissue. The tissues in gastrointestinal teratomas are usually fully differentiated except for gastric teratomas in which areas of immature neural tissue may be found. It is important to establish a pre-operative diagnosis of gastric teratomas, as they are clinically benign thereby allowing elective surgical treatment. Although the number of published cases is small, the prognosis following surgical resection has been excellent. Hence, accurate diagnosis facilitated by appropriate radiological investigations with subsequent histopathological confirmation is mandatory.

References

- 1.Grosfeld JL, Ballantine TVN, Lowe D, Baechner RL. Benign and malignant teratomas in children: analysis of 85 patients. Surgery. 1976;80:297–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahour GH, Woolley MM, Trivedi SN, Landing BH. Teratomas in infancy and childhood: experience with 81 cases. Surgery. 1974;76(2):309–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunlap JP, James CA, Maxson RT, Bell JM, Wagner CW. Gastric teratoma with intramural extension. Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25:383–384. doi: 10.1007/BF02021715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Senocak ME, Kale G, Buyukpamukcu N, Hicsonmez A, Caglar M. Gastric teratomas in children including the third reported female case. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:681–684. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(90)90363-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moriuchi A, Nakayama I, Muta H, Tiara Y, Takahara O, Yokoyama S. Gastric teratomas in children - a case report with review of literature. Acta Path Jap. 1977;27(5):749–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1977.tb00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cairo MS, Grosfeld JL, Wheetman RM. Gastric teratomas: unusual cause for bleeding of the upper gastrointestinal tract in the newborn. Pediatrics. 1981;67:721–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganopadhyay AN, Pandit SK, Gopal CS. Gastric teratomas revealed by gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Ind Pediatrics. 1992;29:1145–1146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohan V, Gupta SK, Chooramani S, Arora M. Gastric teratomas in infancy. Ind J Radiol. 1980;36(3):239–241. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowen B, Ros PR, MC Carthy MJ, Olmsted WW, Hjermstad BM. Gastric teratomas: CT and US appearance with pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1987;162:431–433. doi: 10.1148/radiology.162.2.3541031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]