Abstract

Social withdrawal, or refraining from social interaction in the presence of peers, places adolescents at risk of developing emotional problems like anxiety and depression. The personality traits of neuroticism and conscientiousness also relate to emotional difficulties. For example, high conscientiousness predicts lower incidence of anxiety disorders and depression, while high neuroticism relates to greater likelihood of these problems. Based on these associations, socially withdrawn adolescents high in conscientiousness or low in neuroticism were expected to have lower levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Participants included 103 adolescents (59% female) who reported on their personality traits in 8th grade and their anxiety and depressive symptoms in 9th grade. Peer ratings of social withdrawal were collected within schools in 8th grade. A structural equation model revealed that 8th grade withdrawal positively predicted 9th grade anxiety and depressive symptoms controlling for 8th grade anxiety and depressive symptoms, but neuroticism did not. Conscientiousness moderated the relation of withdrawal with depressive symptoms but not anxiety, such that high levels of conscientiousness attenuated the association between withdrawal and depressive symptoms. This buffering effect may stem from the conceptual relation between conscientiousness and self-regulation. Conscientiousness did not, however, moderate the association between withdrawal and anxiety, which may be partly due to the role anxiety plays in driving withdrawal. Thus, a conscientious, well-regulated personality partially protects withdrawn adolescents from the increased risk of emotional difficulties.

Keywords: social withdrawal, personality, neuroticism, conscientiousness, internalizing problems

Introduction

Social withdrawal, or refraining from peer interactions in a social context, has been shown to predict a variety of negative social and emotional outcomes for children and adolescents, including poor social competence, rejection and victimization by peers, low self-esteem and perceived competence, and emotional difficulties like anxiety and depression (see Rubin, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009, for a review). Researchers have suggested that these links occur because those youth who refrain from engaging in social interaction and avoid the company of their peers fail to develop the social-cognitive (e.g., social information processing; Burgess, Wojslawowicz, Rubin, Rose-Krasnor, & Booth-LaForce, 2006) and social competencies (e.g., Stewart & Rubin, 1995) necessary to develop strong, positive relationships with their peers. Furthermore, the expression of solitary behavior in the company of peers predicts peer rejection and exclusion (e.g., Gazelle and Spangler, 2007), which, in turn, leads to the development of negative self-perceptions of social skills and relationships, loneliness, rejection sensitivity, and such internalizing difficulties as anxiety and depression (e.g., Ladd, 2006).

However, individual characteristics and dispositions may alter the relations between the expression of socially withdrawn behavior and these negative outcomes. For instance, adolescents’ motivations for withdrawing from the peer group predict the extent to which they experience negative social and emotional outcomes (Rubin et al., 2009). Adolescents who withdraw from social interaction because of shyness, or wariness and anxiety about interacting with peers, tend to report especially high levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms (Coplan, Rose-Krasnor, Weeks, Kingsbury, Kingsbury, & Bullock, 2013). Rubin and Burgess (2001) proposed that shy children may be particularly prone to internalizing symptoms in part because their withdrawn behavior is driven by very high levels of social anxiety, and in part because they strongly desire to interact with peers but find themselves incapable of doing so, which provokes feelings of sadness and inadequacy. In contrast, those who are socially withdrawn because they prefer solitude generally experience lower levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms, perhaps because their behavior is not motivated by high levels of anxiety and they experience less negative affect from a lack of social interaction (Coplan et al., 2013). The experiences of socially withdrawn children also differ based on demographic characteristics like gender. Socially withdrawn boys tend to experience more social and emotional problems than withdrawn girls, likely because reticent and passive behavior is particularly incompatible with male gender norms and expectations (see Doey, Coplan, & Kingsbury, 2014, for a review). Socially withdrawn adolescents also differ in their social experiences with peers. Since socially withdrawn behavior is often perceived by other children as unusual and deviant, many children who display socially withdrawn behavior experience peer rejection, which refers to peers expressing a negative attitude toward the child (Pedersen, Vitaro, Barker, & Borge, 2007). This peer rejection is sometimes accompanied by exclusion, in which other children refuse to interact with or befriend the withdrawn child (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003). Exclusion is distinct from social withdrawal in that the construct of social withdrawal describes voluntary, self-imposed solitude from the peer group, whereas exclusion describes forcible expulsion from the peer group (Rubin & Coplan, 2004). Socially withdrawn children who subsequently experience peer rejection or exclusion tend to experience particularly high levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms compared with withdrawn children who have more positive peer experiences (Nelson, Rubin, & Fox, 2005). Therefore, a variety of individual characteristics and unique social experiences predict variation in the extent to which socially withdrawn children and adolescents suffer from internalizing symptoms.

One important, yet virtually ignored construct likely to have an impact on the relation between withdrawal and internalizing problems is personality. One of the most widely used systems for describing individual characteristics is the Big Five Factor model of personality, which includes the traits of extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, conscientiousness, and openness to experience (e.g., Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005). Of these five, neuroticism and conscientiousness have the most evident conceptual links to internalizing problems. In a formulation of the Big Five traits, Caspi and Shiner (2006) defined neuroticism as the frequent experience of negative emotions such as anger, fear, and sadness, and conscientiousness as self-control, planfulness, and persistence. Thus, neuroticism may increase the risk of internalizing problems because highly neurotic individuals frequently experience the negative emotions that underlie such disorders as anxiety and depression. On the other hand, conscientiousness may decrease the risk of internalizing problems because it describes better self-regulation and, potentially, the ability to regulate emotions. According to the Big Five model, these traits are relatively stable over time, although some degree of developmental change in personality has been documented (Caspi & Shiner, 2006).

In the present study, we examined how and whether the personality traits of neuroticism and conscientiousness exacerbated or attenuated the association between socially withdrawn behavior and internalizing problems among adolescents transitioning to high school. To investigate this question, we examined how peer-reported social withdrawal and self-reported personality traits in 8th grade related to self-reported anxiety and depressive symptoms one year later in 9th grade, and whether neuroticism and conscientiousness moderated these relations. Thus, the current study contributes to the literature on adolescent internalizing problems by examining how two key personality traits relate to anxiety and depressive symptoms during the high school transition and how they interact with social withdrawal to predict emotional difficulties.

Internalizing Problems during the High School Transition

Adolescence has been identified as a particularly stressful developmental period, as internalizing symptoms like anxiety and depressed mood are highly prevalent among adolescents and psychological disorders like generalized anxiety disorder and major depression often begin during the adolescent years (Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005; Kessler et al., 2012). The transition from middle school to high school may be a particularly challenging process, as adolescents must adjust to a new academic and social context and often experience disruptions in their social support from parents and peers as a result (Newman, Newman, Griffen, O’Connor, and Spas, 2007). Students transitioning from middle to high school often move from a school with a relatively small, familiar student body into a school with a larger, more diverse group of students that includes many unfamiliar peers (Sable & Hill, 2006). Accordingly, adolescents tend to report a decreased sense of school belonging and lower school engagement after the high school transition (Barber & Olsen, 2004). At the same time, support from parents and teachers tends to decline across this transition period, which requires adolescents to navigate this broader social context largely independently (Newman et al., 2007). Likely as a consequence of these social support changes, adolescents generally report higher levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and loneliness and lower self-esteem during their first year of high school than in the final year of middle school (Barber & Olsen, 2004; Benner & Graham, 2009). Furthermore, this transition is likely to be particularly stressful for socially withdrawn youth because withdrawn individuals tend to have difficulty forming and maintaining social relationships. For example, withdrawn adolescents tend to have fewer friends than their typical peers, and they have lower-quality friendships characterized by a relative lack of intimacy, closeness, and support (Pedersen et al., 2007; Rubin, Wojslawowicz, Rose-Krasnor, Booth-LaForce, & Burgess, 2006). Socially withdrawn adolescents are also especially likely to be rejected by peers, and they may anxiously anticipate rejection in high school if they have experienced peer rejection in the past (Wang, McDonald, Rubin, & Laursen, 2012). Therefore, the disruptions in friendships and peer support that often accompany the transition to high school may be especially damaging to withdrawn youths’ already fragile social networks, placing them at particular risk of heightened anxiety and depressive symptoms during this period.

Social Withdrawal and Internalizing Problems

Social withdrawal has a bidirectional relation to internalizing problems, as it is a symptom of a variety of internalizing disorders including several anxiety disorders and major depression, in addition to being a predictor of emotional problems throughout childhood and adolescence (Rubin & Burgess, 2001). Individuals with elevated levels of anxiety may respond fearfully to social situations and withdraw from interaction as a result, while those with high levels of depressive symptoms may doubt their ability to interact effectively and anticipate rejection from peers, leading them to withdraw from social interaction (Joiner & Timmons, 2002). In turn, this withdrawn behavior prevents them from accessing social support from peers and may reinforce feelings of inadequacy and loneliness (Rubin et al., 2009). While socially withdrawn behavior is often motivated in part by internalizing symptoms, many studies of children and adolescents have focused on social withdrawal as an antecedent of increasing internalizing symptoms over time, since socially withdrawn behavior predicts a variety of negative social and emotional consequences that place children and risk of anxiety and depressive symptoms. As early as age 7, withdrawn children perceive themselves as less socially competent and feel less accepted by peers (Nelson et al., 2005). Hymel, Rubin, Rowden, and LeMare (1990) found that socially withdrawn second-graders tended to perceive themselves as having relatively poor social competence and had higher teacher-reported internalizing symptoms; these emotional difficulties generally remained stable through fifth grade. Elementary school children who report high levels of wariness and hesitance to interact with peers also report experiencing high levels of loneliness, negative affect, and social anxiety, as well as a poorer self-concept and lower overall well-being (Findlay, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009). Similarly, Gazelle and Ladd (2003) showed that children who were socially withdrawn in kindergarten experienced elevated levels of depressive symptoms and increasing levels of depressive symptoms across childhood. Children identified by parents as withdrawn during childhood are more likely than their non-withdrawn peers to report high levels of anxiety as adolescents (Prior, Smart, Sanson, & Oberklaid, 2000). In late childhood and early adolescence, shy, socially withdrawn youth report higher levels of negative affect, social anxiety, depressive symptoms, and a more negative attributional style than their non-withdrawn peers (Coplan et al., 2013). In late adolescence and early adulthood, socially withdrawn individuals continue to report high levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms and low self-esteem (Nelson, Padilla-Walker, Badger, Barry, Carroll, & Madsen, 2008). In sum, it seems likely that social withdrawal may predict internalizing difficulties both directly, because social withdrawal is often motivated by wariness and anxiety, and indirectly, because socially withdrawn children often experience peer rejection and victimization that may foster negative self-perceptions of social competence, negative self-esteem, and emotional problems (Rubin et al., 2009).

Neuroticism and Internalizing Problems

Researchers have consistently demonstrated that the personality trait of neuroticism is among the strongest predictors of such internalizing problems as anxiety and depression because neuroticism describes the frequent experience of negative affect that is thought to play a role in mood disorders. Research on the link between neuroticism and internalizing has shown that adults with a lifetime history of anxiety or depressive disorders score significantly higher on measures of neuroticism than those with no history of those disorders (Bienvenu et al., 2004). Likewise, two meta-analyses of studies with adult participants demonstrated that neuroticism was highly associated with symptoms of internalizing disorders, especially mood disorders such as anxiety and depression (Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt, & Watson, 2010; Malouff, Thorsteinsson, & Schutte, 2005). Among individuals aged 15 to 54, neuroticism is moderately positively correlated with major depression and generalized anxiety disorder, and this association is driven by high correlations between neuroticism and symptoms of depressed mood, anhedonia, and nervousness (Watson, Gamez, & Simms, 2005). In a study of depression among older adults, neuroticism was shown to strongly predict the onset of depression even in the absence of stressful life events (Ormel, Oldehinkel, & Brilman, 2001).

Some research has begun to suggest similar relations between neuroticism and internalizing problems among children and adolescents. For instance, self-, mother-, and teacher-reported neuroticism is positively associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms for children in late elementary school (Barbaranelli, Caprara, Rabasca, & Pastorelli, 2003); although, other researchers have found that neuroticism positively predicts anxiety symptoms but not depressive symptoms (Kushner, Tackett, & Bagby, 2012). Adolescents with anxiety or mood disorders report higher levels of neuroticism than adolescents without psychological disorders, and those with comorbid anxiety and mood disorders report greater neuroticism than those with only one type of disorder (Griffith et al., 2010). A longitudinal study by Klimstra, Akse, Hale, Raaijmakers, and Meeus (2010) showed that neuroticism and depressive symptoms were bidirectionally related across adolescence, such that high levels of neuroticism predicted increasing depressive symptoms over several years, and frequent depressive symptoms predicted high scores for neuroticism over several years.

Neuroticism has also been shown to moderate the relation between risk factors for emotional difficulties and the development of internalizing problems. For instance, the positive relation between daily hassles and depressive symptoms is significantly stronger at high levels of neuroticism (Hutchinson & Williams, 2007), and neuroticism exacerbates the relation between conflict in close relationships and subsequent depressive symptoms (Davila, Karney, Hall, & Bradbury, 2003). Neuroticism might also be expected to moderate the relation between social withdrawal and emotional difficulties because adolescents who frequently experience negative emotions may be more strongly affected by the negative social experiences or lack of social support that often result from socially withdrawn behavior with peers. If adolescents are highly neurotic, then the social isolation and the lack of positive peer interactions that often accompany socially withdrawn behavior may easily provoke feelings of nervousness and sadness that develop into symptoms of anxiety and depression. On the other hand, socially withdrawn adolescents who are not prone to experiencing negative emotions may not experience as much fear or sadness as a result of the negative social consequences of withdrawn behavior. Therefore, one might expect a significantly stronger relation between social withdrawal and anxiety and depressive symptoms among highly neurotic adolescents, who are more likely to experience negative emotions as a result of adverse experiences.

Conscientiousness and Internalizing Problems

Whereas neuroticism is significantly associated with an increased risk of internalizing symptoms, conscientiousness has been linked to a decreased risk of anxiety and depression in adults. Two meta-analyses have demonstrated that conscientiousness is strongly negatively associated with a wide variety of psychological disorders in adults, including mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and such externalizing problems as substance use (Kotov et al., 2010; Malouff et al., 2005). Adults with a lifetime history of anxiety or depressive disorders tend to score lower on measures of conscientiousness than those with no history of psychopathology, particularly on the self-discipline subscale (Bienvenu et al., 2004).

Some evidence also suggests that conscientiousness predicts decreased incidence of internalizing problems for children and adolescents. In late childhood, mother- and teacher-reported conscientiousness have been shown to negatively predict internalizing symptoms (Barbaranelli et al., 2003). Conscientiousness may have particularly strong associations with depressive symptoms, as Kushner and colleagues (2012) found that conscientiousness negatively predicted adolescents’ depressive symptoms but did not relate to anxiety. Similarly, Klimstra and colleagues (2010) showed that conscientiousness and depressive symptoms were bidirectionally negatively related across adolescence, such that high conscientiousness predicted fewer depressive symptoms over several years, and high levels of depressive symptoms predicted decreases in conscientiousness over time.

Conscientiousness may be related to lower incidence of internalizing problems because of its relation to self-regulation and the ability to direct attention. Among adults, high conscientiousness predicts higher levels of positive affect, and this relation is mediated by positive skills for coping with stress and negative emotions (Bartley & Roesch, 2011). Further, conscientiousness has conceptual links to the temperament trait of effortful control, which describes self-regulatory abilities and the capacity to control attention and behavior (Eisenberg, Duckworth, Spinrad, & Valiente, 2014). Adults with high effortful control have been shown to experience negative emotions less frequently (Bridgett, Oddi, Laake, Murdock, & Bachmann, 2013), and adults who more effectively control their attention report experiencing less negative affect in response to distressing situations (Compton, 2000). Among young adolescents, effortful control, particularly the attentional control dimension, is negatively related to internalizing symptoms (Muris, Meesters, & Blijlevens, 2007). In a longitudinal study, effortful control robustly negatively predicted internalizing problems for young adolescents over a three-year period (Lengua, Bush, Long, Kovacs, & Trancik, 2008). Therefore, conscientiousness may similarly predict decreased risk of internalizing symptoms because strong self-regulation and the ability to focus attention adaptively appear to protect against the experience of negative emotions.

In addition to its direct relation to internalizing difficulties, conscientiousness may moderate the relation between social withdrawal and anxiety and depressive symptoms via its effect on adolescents’ emotional experiences and their social behavior. First, highly conscientious withdrawn adolescents may be able to focus their attention away from negative emotions that they experience as a result of their social isolation and potentially negative peer interactions, allowing them to avoid dwelling on feelings of nervousness or sadness that can develop into anxiety and depressive symptoms. Second, withdrawn adolescents high in conscientiousness may demonstrate relatively high levels of social competence when they do interact with peers, as conscientiousness is positively associated with social competence and the ability to avoid negative social behaviors (Lianos, 2015; Jensen-Campbell, Knack, Waldrip, & Campbell, 2007). As a result, conscientious withdrawn children may be less likely to experience peer rejection or victimization, which often accompany socially withdrawn behavior and predict later anxiety and depressive symptoms (Pedersen et al., 2007). Thus, high levels of conscientiousness may protect socially withdrawn adolescents from negative social experiences and negative emotional reactions that predict the development of internalizing difficulties like anxiety and depressive symptoms.

The Current Study

While prior research has demonstrated clear links between the personality traits of neuroticism and conscientiousness and internalizing symptoms among adults, relatively few studies have examined relations between these traits and emotional difficulties among adolescents and none have examined the high school transition in particular. Thus, the first goal of the present study was to examine whether neuroticism and conscientiousness in 8th grade predict anxiety and depressive symptoms during the first year of high school. We hypothesized that neuroticism would positively predict later anxiety and depressive symptoms, while conscientiousness would negatively predict anxiety and depressive symptoms. Furthermore, while researchers have reliably demonstrated that social withdrawal is associated with heightened levels of internalizing symptoms, they have yet to examine whether major personality dimensions such as neuroticism and conscientiousness may alter the strength of the association between withdrawal and emotional difficulties. Probing the ways in which these individual dispositions relate to the emotional experiences of socially withdrawn adolescents is essential for understanding the heterogeneity of withdrawn individuals’ developmental trajectories and outcomes, and may ultimately inform more effective strategies for preventing internalizing problems among withdrawn adolescents. Therefore, the second goal of the present study was to examine whether neuroticism may exacerbate the risk of internalizing problems for socially withdrawn adolescents, and whether conscientiousness may protect withdrawn adolescents from the increased risk of internalizing difficulties. We hypothesized that social withdrawal would positively predict anxiety and depressive symptoms, but this main effect would be qualified by interactions with the personality traits. We hypothesized that neuroticism would moderate the relation between social withdrawal and internalizing problems such that adolescents with high levels of withdrawal and high levels of neuroticism would report the most anxiety and depressive symptoms as these youth made the often stressful transition from middle to high school (Barber & Olsen, 2004; Isakson & Jarvis, 1999). In addition, we hypothesized that conscientiousness would moderate the relation between social withdrawal and internalizing such that social withdrawal would predict internalizing problems most strongly among adolescents low in conscientiousness.

Methods

Participants

Participants in this study comprised a longitudinal sample of adolescents as they transitioned from the final year of middle school (8th grade) to the first year of high school (9th grade). Questionnaires were distributed to 263 adolescents in 8th grade, after having received parental permission to participate in the study. Nine of those adolescents declined to complete the questionnaires, and 73 adolescents attended schools that declined to participate in the study, preventing the collection of peer report data. As a result, 181 participants (68.8% of the sample) had complete data on the personality measures and peer nominations collected in 8th grade, and 103 of those participants chose to complete measures of anxiety and depressive symptoms in 9th grade.

Participants with complete data in 9th grade scored higher on conscientiousness than those without complete data, t (179) = −2.07 p = .04, which is consistent with the fact that conscientious individuals are particularly diligent and likely to follow through on their commitments. However, participants with complete data did not differ from those without complete data on neuroticism, t (179) = 1.199, p = .232, peer-reported social withdrawal, t (179) = −1.020, p = .309, or self-reported internalizing problems, t (176) = 0.63 p = .528. Those with complete data also did not differ from those without complete data on demographic variables including gender, χ2 (1) = 0.14 p = .704, ethnicity, χ2 (5) = 0.64, p = .986, and mothers’ education level, χ2 (8) = 11.44, p = .178. Little’s MCAR test showed no support for the hypothesis that data were not missing completely at random, χ2 (186) = 179.66, p = .617.

The final sample included 103 adolescents (42 males) who were on average, 13.63 years old in 8th grade (SD = 0.56). The sample was ethnically diverse, as 55.3% of participants identified themselves as European American, 16.5% identified as Asian American, 11.7% identified as African American, 6.9% identified as Latino/Hispanic, and 8.8% identified as another ethnicity. Participants were generally relatively advantaged in terms of socioeconomic status as indexed by maternal education level; 4.9% of mothers had completed high school or less, 18.5% had completed some college, 33.1% had obtained a university degree, and 30.1% had earned a graduate degree. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participants, and assent was obtained from all participating adolescents.

Procedure

Participants were initially recruited in 6th grade from three middle schools in the greater Washington, D.C. metropolitan area as part of a larger longitudinal study. Adolescents who participated in the study in 6th grade were contacted again in the fall of their 8th grade school year, and they were mailed a packet of questionnaires about their personality and internalizing symptoms after their parents consented to participate. One of the three middle schools agreed to continue participating in the study when participants were in 8th grade, and participants attending that school completed a group-administered questionnaire about their classmates’ behavior, including socially withdrawn behavior. In the fall of their 9th grade school year, participants were asked to complete online questionnaires about their anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Measures

Social withdrawal

Social withdrawal was measured using the Extended Class Play (e.g., Burgess et al., 2006), a peer-report questionnaire administered in 8th grade in which adolescents were asked to imagine that they were directing a school play and cast their classmates in a variety of positive and negative roles. A peer-report measure of social withdrawal was used instead of a self-report measure such as the withdrawal scale of the Youth Self-Report (Achenbach, 1991) because the focus of the current study was to examine socially withdrawn behavior as observed by peers, rather than adolescents’ own subjective perceptions of their withdrawn behavior and their underlying motivations for the expression of withdrawal. Participants were provided with a list of students in their grade at their school and asked to nominate three boys and three girls for each of 37 different roles. To eliminate possible gender stereotyping, only same-gender nominations were considered (Zeller, Vannatta, Schafer, & Noll, 2003). All item scores were standardized within grade and gender to account for the number of nominators. A composite score for the behavioral expression of social withdrawal was formed by calculating the mean score for three items: “Doesn’t talk much or talks quietly,” “Rarely starts conversations,” and “Stays by self.” In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.82. The three items were highly intercorrelated, as items 1 and 2 had a correlation of .756, items 2 and 3 had a correlation of .532, and items 1 and 3 had a correlation of .550.

Personality traits

The traits of conscientiousness and neuroticism were measured with the Big Five Inventory (John & Srivastava, 1999), which participants completed in 8th grade. The conscientiousness subscale consisted of 9 items, such as “I see myself as someone who is thorough when I do a job,” and “I see myself as someone who perseveres until the task is finished.” The neuroticism subscale contained 8 items, including “I see myself as someone who can be tense,” and “I see myself as someone who can be moody.” Participants rated how much each item applied to them on a 5-point scale ranging from Strongly disagree to Strongly agree, and scores for the items on each subscale were averaged to create an overall score for each trait. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .81 for the conscientiousness subscale and .84 for the neuroticism subscale.

Anxiety/depression

Internalizing problems in 8th grade were measured using the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach, 1991), a 112-item questionnaire that measures a wide variety of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. The anxious/depressed subscale included 12 items that participants rated on a 3-point scale from Not true to Very true, including items such as “I cry a lot” and “I am nervous or tense.” A total score for the subscale was created by averaging the relevant items. Cronbach’s alpha for the anxious/depressed subscale was .77.

Anxiety

Anxiety was measured using the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997), which participants completed in 9th grade. The MASC consists of 39 items that capture four dimensions of anxiety: 1) physical symptoms, which includes subscales for tense/restless and somatic/autonomic symptoms, 2) social anxiety, including subscales for humiliation/rejection and public performance fears, 3) harm avoidance, with subscales for perfectionism and anxious coping, and 4) separation anxiety. Participants reported how well each item described them on a 4-point scale ranging from Never true to Often true, and a total score for each subscale was formed by averaging the relevant items. In the current study, Cronbach’s alphas for the subscales ranged from .67 to .85.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992), completed by participants in 9th grade. The CDI includes 27 items that represent five dimensions of depressive symptomology: negative mood, interpersonal problems, ineffectiveness, anhedonia, and negative self-esteem. Participants selected one of three statements that reflect varying levels of symptom severity during the past two weeks, with the first statement indicating that the symptom was absent, the second statement indicating a moderate level of the symptom, and the third statement indicating a high level of the symptom. Endorsement of the statement indicating lack of the symptom was scored as a 0, selection of the statement indicating moderate levels of the symptom was scored as a 1, and endorsement of the statement indicating high symptom levels was scored as a 2. Then the scores for each item were averaged to create subscale scores. In the current study, Cronbach’s alphas for the subscales ranged from .62 to .76.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 1. Grade 8, peer-assessed social withdrawal was moderately and positively correlated with self-reported total anxiety symptoms and total depressive symptoms in 9th grade. Grade 8 conscientiousness was moderately and negatively correlated with neuroticism, 8th grade anxiety/depressive symptoms, and the total scores for 9th grade anxiety and depressive symptoms. Grade 8 neuroticism was moderately and positively correlated with 8th grade anxiety/depression scores and total scores for 9th grade anxiety and depressive symptoms. Anxiety/depression in 8th grade was significantly and positively correlated with total 9th grade anxiety and depressive symptoms, and scores for total anxiety and depressive symptoms in 9th grade were moderately and positively correlated with one another.

Table 1.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics Among All Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social Withdrawal | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. Conscientiousness | −.08 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Neuroticism | .02 | −.38** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 4. YSR Anxious/Depressed | .09 | −.29** | .60** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 5. MASC Tense/Restless | .25* | −.35** | .34** | .56** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 6. MASC Somatic/Autonomic | .18 | −.23* | .30** | .44** | .72** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 7. MASC Humiliation/Rejection | .13 | −.26** | .42** | .54** | .57** | .42** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 8. MASC Performance Fears | .27** | −.24* | .43** | .53** | .69** | .51** | .70** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 9. MASC Perfectionism | .03 | .30** | −.01 | .11 | −.02 | −.02 | .30** | .21* | 1 | |||||||||

| 10. MASC Anxious Coping | −.01 | −.04 | .18 | .35** | .39** | .311** | .41** | .40** | .49** | 1 | ||||||||

| 11. MASC Separation Anxiety | .06 | −.27** | .23* | .41** | .56** | .54** | .55** | .55** | .11 | .47** | 1 | |||||||

| 12. MASC Total Anxiety Score | .20* | −.21* | .40** | .60** | .80** | .68** | .82** | .83** | .43** | .70** | .66** | 1 | ||||||

| 13. CDI Negative Mood | .16 | −.20 | .31** | .34** | .47** | .48** | .32** | .31** | −.17 | .14 | .29** | .37** | 1 | |||||

| 14. CDI Interpersonal Problems | .31** | −.35** | .37** | .27** | .37** | .34** | .09 | .17 | .33** | .03 | .08 | .17 | .62** | 1 | ||||

| 15. CDI Ineffectiveness | .14 | −.37** | .29** | .13 | .29** | .25* | .16 | .26** | .24* | −.07 | .11 | .16 | .64** | .58** | 1 | |||

| 16. CDI Anhedonia | .30** | −.29** | .55** | .35** | .55** | .49** | .37** | .41** | −.18 | .10 | .26** | .42** | .77** | .66** | .67** | 1 | ||

| 17. CDI Negative Self-esteem | .24* | −.26** | .41** | .25* | .41** | .40** | .30** | .34** | −.23* | .09 | .28** | .32** | .81** | .68** | .72** | .80** | 1 | |

| 18. CDI Total Depression Score | .27** | −.32** | .33** | .32** | .50** | .47** | .32** | .36** | −.24* | .07 | .25* | .36** | .90** | .77** | .82** | .92** | .92** | 1 |

| Mean | .05 | 3.53 | 2.58 | 4.35 | 3.46 | 2.35 | 5.21 | 3.91 | 7.59 | 7.40 | 5.12 | 29.92 | 2.14 | 0.55 | 1.43 | 2.46 | 1.18 | 7.61 |

| SD | .96 | .69 | .85 | 3.71 | 3.34 | 2.60 | 3.74 | 3.01 | 2.53 | 3.20 | 4.05 | 13.31 | 2.47 | 1.09 | 1.68 | 2.80 | 1.82 | 8.61 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01

Predictors and Moderators of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms

Analyses were performed using the lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) package in the freely available statistical computing software R (R Core Team, 2014). The lavaan package allows researchers to develop a wide variety of structural equation models including but not limited to measured variable path analyses, latent variable path analyses, and latent growth models. In the present set of analyses, we used full information maximum likelihood estimation, as there were some missing data in reports on negative mood (n = 11) and 8th grade anxiety/depression as assessed by the YSR (n = 1).

We began our modeling process by fitting a measurement model using subscales of the CDI and MASC as indicators of latent variables representing depressive symptoms and anxiety respectively. Initially, all five subscales of the CDI and all six subscales of the MASC were included in the model. Errors were free to covary between the following pairs of indicator variables as they comprise composite scores on the MASC: a) tense/restless and somatic, b) perfectionism and anxious coping, and c) humiliation/rejection and performance fears. This initial model did not fit the data well, χ2 (40) = 76.08, p = .001, RMSEA = .09, CFI = .95, SRMR = .09, AIC = 4585.14. The data-model fit discrepancy appeared to be largely driven by the fact that perfectionism did not significantly load onto the latent variable representing anxiety (p = .928). Therefore, we dropped this indicator from our first measurement model and all subsequent models. Next, we further refined our measurement model by freeing covariances among indicator variables, using modification indices as a guide (see Table 2). We decided it was appropriate to allow error covariances across indicators of each latent variable, as anxious and depressive symptoms are often comorbid in children and adolescents (e.g., Seligman & Ollendick, 1998). The final measurement model fit the data well, χ2 (27) = 28.62, p = .380. Average variance extracted by the latent variables representing depressive symptoms and anxiety was .69 and .49 respectively. See Table 3 for a summary of parameter estimates, loadings, and construct reliability.

Table 2.

Summary Data of Model Fit for Measurement Models

| Parameter Added | df | AIC | Δχ2 | RMSEA | CFI | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | – | 32 | 4129.68 | 51.31* | .08 | .97 | .07 |

| Model 2 | Negative Mood ~ Somatic Problems | 31 | 4127.28 | 4.40* | .07 | .98 | .07 |

| Model 3 | Negative SE ~ Tense/Restless | 30 | 4123.23 | 6.05* | .06 | .98 | .06 |

| Model 4 | Interpersonal ~ Humiliation/Rej | 29 | 4121.38 | 3.89* | .05 | .99 | .06 |

| Model 5 | Interpersonal ~ Performance Fear | 28 | 4119.37 | 3.97* | .04 | .99 | .06 |

| Model 6 | Ineffectiveness ~ Anxious Coping | 27 | 4116.98 | 4.38* | .02 | 1.00 | .05 |

Note. AIC = Akaike Information Criteria, RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, CFI = Comparative Fit Index, SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual.

An initial measurement model revealed that perfectionism did not significantly load onto a latent variable representing anxiety. As a result, perfectionism was dropped from Model 1 and was not included in any subsequent measurement models.

p < .05

Table 3.

Final Measurement Model Parameter Estimates

| Estimate | SE | λ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressiona | H = .90b | |||

| Negative Mood | 2.05 | 0.19 | .86 | |

| Interpersonal Problems | 0.79 | 0.09 | .73 | |

| Ineffectiveness | 1.23 | 0.14 | .75 | |

| Anhedonia | 2.46 | 0.22 | .88 | |

| Negative Self-Esteem | 1.68 | 0.14 | .92 | |

| Anxiety | H = .87 | |||

| Tense/Restless | 3.00 | 0.31 | .91 | |

| Somatic Problems | 1.84 | 0.27 | .72 | |

| Anxious Coping | 1.30 | 0.33 | .41 | |

| Humiliation/Rejection | 2.31 | 0.38 | .62 | |

| Performance Fears | 2.23 | 0.29 | .75 |

Note. All p’s < .001

The depression and anxiety factors were positively and significantly correlated, r = .57, p < .001.

Coefficient H is a measure of construct reliability, akin to Cronbach’s α, though more appropriate for use in latent variable models (Hancock & Mueller, 2001).

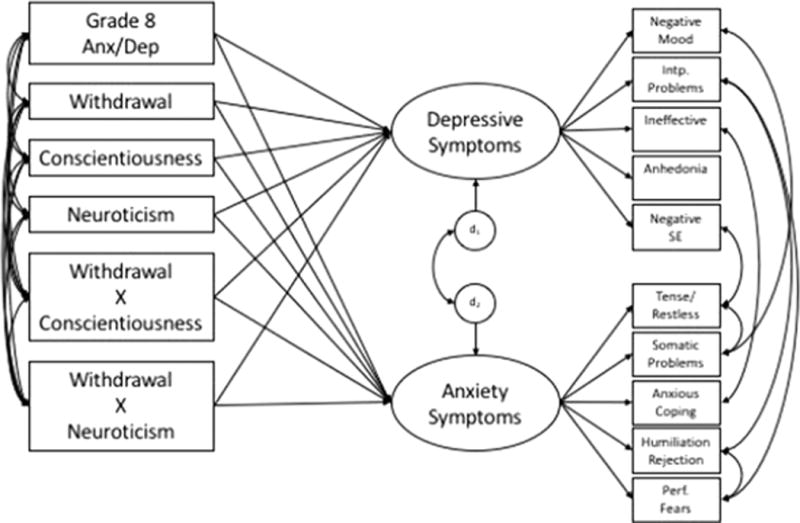

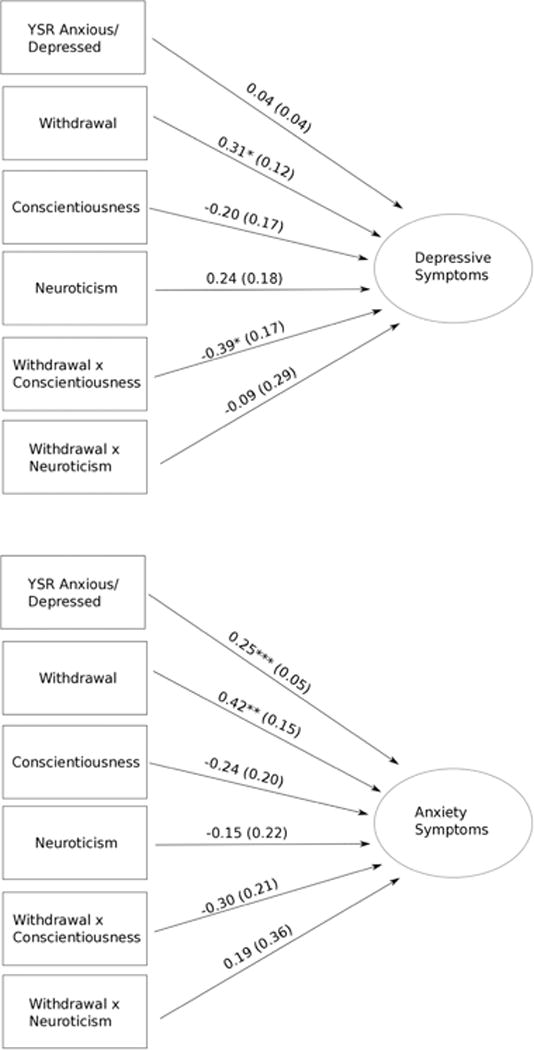

Having developed an appropriate measurement model, we next added predictors of 9th grade depressive symptoms and anxiety as follows: 8th grade self-reported anxiety/depression on the YSR; mean-centered peer-rated withdrawal in 8th grade; mean-centered self-reported conscientiousness in 8th grade; mean-centered self-reported neuroticism in 8th grade; and both two-way interaction terms between the two personality variables and 8th grade withdrawal (see Figure 1 for graphic depiction). Following the addition of these predictors, the model demonstrated acceptable data-model fit, χ2(75) = 108.69, p = .007, RMSEA = .07, CFI = .95, SRMR = .06. Parameter estimates for the structural portion of the model are displayed in Figure 2.

Fig. 1.

Graphical depiction of the final structural equation model

Fig. 2.

Depiction of the final structural equation model with unstandardized path estimates. Standard errors are shown in parentheses

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

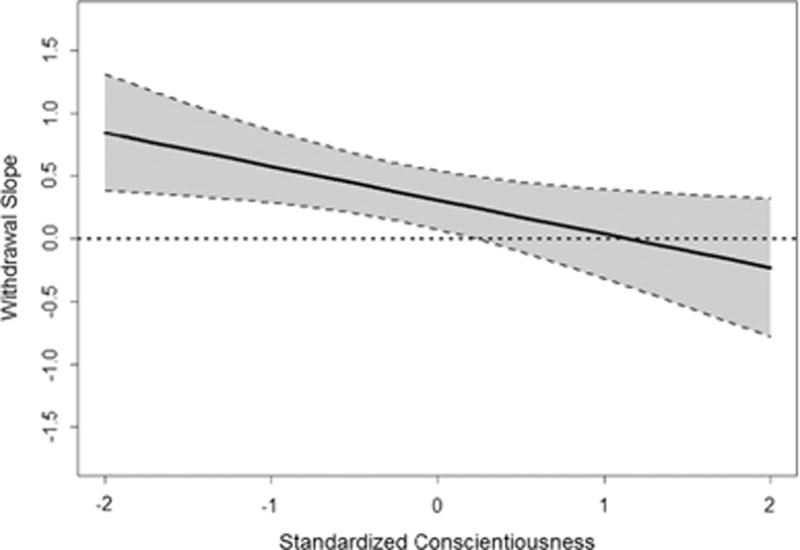

In total, the predictors explained 32% of the variance in the latent depressive symptoms factor and 61% of the variance in the latent anxiety factor. Controlling for grade 8 internalizing problems and personality self-reports, peer-rated social withdrawal in 8th grade was positively related to both depressive symptoms (p = .01) and anxiety (p = .004) in 9th grade. The association between withdrawal and depressive symptoms was, however, qualified by a significant interaction with conscientiousness (p = .021). Simple slopes analyses at high and low levels of conscientiousness (i.e., ±1 SD) revealed that at low levels of conscientiousness, the association between withdrawal and depressive symptoms was significant and positive (b = 0.57, z = 3.86, p < .001). At high levels of conscientiousness, the association between withdrawal and depressive symptoms was reduced to non-significance (b = 0.04, z = 0.20, p = .838; see Figure 3). The only other significant relation detected was that between self-reported anxiety/depression in 8th grade and 9th grade anxiety (p < .001). Neither neuroticism nor conscientiousness predicted each outcome alone, and the interaction between neuroticism and withdrawal was not significant.

Fig. 3.

Depiction of 2-way interaction between peer-rated withdrawal and self-reported conscientiousness in predicting depression scores. Black line represents predicted simple slopes describing the association between withdrawal and depression at different standardized conscientiousness scores. The shaded region bounded by the dashed lines above and below the predicted simple slopes represents the 95% confidence interval for the withdrawal simple slope estimates. A horizontal line centered at y=0 was included to visually identify regions of significance where the estimated simple slope for withdrawal significantly differs from 0

In developing our final structural model, we also sought to test alternative models for which a theoretical basis existed. Given the interaction terms included in the model, there were few alternative path structures to examine. However, we did test one model which placed 8th grade anxiety/depression as a potential mediator linking 8th grade withdrawal, neuroticism, conscientiousness, and withdrawal × personality interactions to internalizing problems in 9th grade. The model revealed a significant indirect path (p < .001) linking neuroticism to 9th grade anxiety via 8th grade reported anxiety/depression. This significant indirect effect would appear to explain the finding that neuroticism in 8th grade was not related to 9th grade anxiety in our original structural model described above. There were no other significant indirect pathways in this alternative model.

Discussion

Previous research has suggested that social withdrawal and neuroticism relate to an increased risk of anxiety and depressive symptoms, whereas conscientiousness predicts a decreased risk of internalizing problems among children and adults (Findlay et al., 2009; Klimstra et al., 2010). The current study extended these findings by examining how neuroticism and conscientiousness relate to internalizing problems during early adolescence and the transition from middle to high school and whether these personality traits interact with peer-perceived withdrawal from social interaction to predict anxiety and depressive symptoms. The results demonstrated that, although neither neuroticism nor conscientiousness was directly predictive of anxiety or depressive symptoms, conscientiousness moderated the relation between social withdrawal and depressive symptoms.

As expected, the behavioral tendency to withdraw from peer interaction in 8th grade significantly predicted both anxiety and depressive symptoms in 9th grade. This finding is consistent with previous studies suggesting that social withdrawal predicts internalizing difficulties throughout childhood and adolescence because social withdrawal is often motivated by social anxiety and low perceived social competence, and the negative peer experiences that accompany social withdrawal reinforce and exacerbate these emotional difficulties (e.g., Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Rubin, Chen, Bowker, & McKinnon, 1995). However, a unique finding of this study was that social withdrawal in the company of 8th grade peers predicted later anxiety and depressive symptoms even after controlling for 8th grade internalizing problems and self-reported conscientiousness and neuroticism.

Unexpectedly, 8th grade neuroticism was not directly related to anxiety or depressive symptoms in 9th grade after controlling for 8th grade anxiety and depressive symptoms, contrary to prior research indicating strong predictive links between neuroticism and internalizing problems (e.g., Klimstra et al., 2010). However, an alternative model revealed a significant indirect path from 8th grade neuroticism to 9th grade anxiety and depressive symptoms, suggesting that neuroticism was related to internalizing symptoms in both 8th and 9th grade, but that the relation to 9th grade symptoms was mediated by internalizing symptoms at the earlier time point. This finding suggests that the effect of neuroticism on internalizing symptoms had already manifested by 8th grade and remained relatively stable from 8th to 9th grade.

Further, neuroticism did not moderate the relation between social withdrawal and internalizing symptoms, contrary to prior research suggesting that neuroticism exacerbates relations between stressful experiences and internalizing symptoms (Davila et al., 2003; Hutchinson & Williams, 2007). The lack of an interaction effect between social withdrawal and neuroticism appears to derive from the fact that neuroticism relates to the level of internalizing symptoms experienced without changing the relation between social withdrawal and those symptoms. Highly neurotic adolescents consistently reported high levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms regardless of their level of social withdrawal, and neurotic individuals who were also socially withdrawn reported the highest levels of internalizing symptoms. However, the positive relation between social withdrawal and internalizing symptoms did not differ at high and low levels of neuroticism, suggesting that neurotic and non-neurotic adolescents reacted similarly to the social stresses that accompany socially withdrawn behavior. This pattern may have arisen because prior studies examining neuroticism as a moderator of the relation between stressors and internalizing symptoms have primarily focused on stressors that originate external to the individual, rather than maladaptive behavior patterns based on motivations internal to the individual such as social withdrawal. It is possible that highly neurotic individuals respond more negatively than non-neurotic individuals to stressful experiences beyond their own control, but they do not experience especially heightened levels of negative affect in response to their own social behaviors. Eysenck (1967) argued that a central component of neuroticism was the predisposition to experience strong negative emotional reactions to adverse events in the environment. However, this heightened negative reactivity may not extend to experiences derived from individuals’ voluntary behaviors. Therefore, neuroticism may not moderate the relation between withdrawal and internalizing symptoms because social withdrawal is a voluntary behavior pattern that stems from such internal motivations as shyness and preference for solitude, which may not be especially challenging for highly neurotic individuals.

In contrast, conscientiousness appeared to buffer socially withdrawn adolescents against heightened levels of depressive symptoms, since the positive association between withdrawal and depressive symptoms one year later was attenuated at high levels of conscientiousness. This finding complements previous studies showing that conscientiousness is consistently associated with a lower incidence of internalizing problems (e.g., Kotov et al., 2010). In part, conscientiousness likely protects against internalizing because it is conceptually related to such abilities as effortful control and attention regulation (Eisenberg et al., 2014); these factors may help individuals focus their attention away from negative emotions and experiences when they occur so that negative emotions do not develop into more serious internalizing problems. Thus, socially withdrawn adolescents who are highly conscientious may be able to efficiently focus their attention away from their social isolation and the sadness that it likely provokes, preventing brief negative experiences from resulting in full-fledged depressive symptoms. In addition, since withdrawn individuals are often less socially competent when interacting with peers (e.g., Burgess et al., 2006; Stewart & Rubin, 1995), the self-discipline and behavioral regulation that comprise conscientiousness may help withdrawn adolescents demonstrate appropriate behavior in the presence of peers. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated that highly conscientious adolescents tend to be more socially competent and less rejected by peers than their less conscientious counterparts (Lianos, 2015; Jensen-Campbell, Knack, Waldrip, & Campbell, 2007). As a result, highly conscientious withdrawn children may be less likely to be rejected or victimized by peers, which might contribute to lower levels of depressive symptoms.

Unexpectedly, conscientiousness did not moderate the relation between social withdrawal and later anxiety. This pattern may be due to the fact that anxiety about interacting with peers, or shyness, has been identified as one of the primary motivations that drives socially withdrawn behavior (Coplan, Prakash, O’Neil, & Armer, 2004). In that case, a relatively high level of anxiety (particularly social anxiety) may be a prerequisite for the display of socially withdrawn behavior among some youth, regardless of conscientiousness. For shy adolescents, social withdrawal may be a manifestation of their anxiety in addition to being a cause of increases in anxiety over time. Thus, socially withdrawn adolescents may experience such high levels of anxiety that they have difficulty appropriately regulating their fearful reactions, even if they have strong self-regulatory abilities. The weaker relation between conscientiousness and anxiety may also arise, in part, because some of the underlying facets of conscientiousness, including perfectionism and achievement focus, may predispose conscientious individuals to relatively high levels of anxiety. The broad trait of conscientiousness encompasses constructs such as persistence and self-control that relate to the ability to regulate behavior, but it also includes aspects such as holding oneself to exacting standards and a desire to achieve high levels of academic or professional success. While the self-regulatory aspects of conscientiousness may buffer withdrawn adolescents against internalizing symptoms, the facets related to setting high performance expectations may predict increased feelings of anxiety among very conscientious youth, as evidenced by the fact that in the current study, conscientiousness was positively correlated with anxiety symptoms related to perfectionism.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths, including the use of peer-report data to assess social withdrawal, a short-term longitudinal design demonstrating prospective relations of withdrawal and personality to internalizing problems, and a relatively diverse sample; however, it also has several limitations. First, the participants included in this study were significantly more conscientious than participants who attrited from the study between 8th and 9th grade. While it makes sense that the most conscientious participants would be the most likely to continue participating in the study, the fact that the sample was comprised of particularly conscientious adolescents poses a potential threat to the validity of the study’s conclusions about the relation of conscientiousness to withdrawal and internalizing difficulties. In addition, different measures of internalizing problems were collected in 8th and 9th grade, with a combined measure of anxiety/depression administered in 8th grade and specific measures of anxiety and depressive symptoms collected the following year. As a result, the analyses controlled for prior levels of internalizing symptoms when predicting 9th grade anxiety and depressive symptoms, but it was not possible to control for prior levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms independently. This incongruity limits the ability to make firm conclusions about the relations of social withdrawal, neuroticism, and conscientiousness with later anxiety and depressive symptoms over and above earlier anxiety and depressive symptoms specifically. Finally, although the study establishes that withdrawal, neuroticism, and conscientiousness precede the development of anxiety and depressive symptoms, the study does not allow for causal conclusions or analysis of any possible bidirectional relations between the variables over time.

Future Directions

The Big Five dimensions of personality are so named because they were intended to be the largest, most global traits into which personality could be divided (Caspi et al., 2005). Therefore, future research on how personality relates to withdrawal and internalizing problems should examine which underlying facets of conscientiousness and neuroticism show the strongest associations with internalizing symptoms and social withdrawal. For instance, within neuroticism, the experience of sadness may relate more strongly to depressive symptoms than the experience of anger. Similarly, the self-discipline and perseverance aspects of conscientiousness might be more important for buffering withdrawn adolescents against the risk of depressive symptoms than the organization or orderliness facets. Future research should also investigate how the facets of the personality traits relate to particular subtypes and symptoms of anxiety and depression, such as social anxiety or anhedonia. Researchers should also examine other personality traits such as openness to experience as possible moderators of the relation between social withdrawal and emotional difficulties. Finally, in the future, researchers might also examine whether personality traits moderate the relation between social withdrawal and negative outcomes in the same way at different transition points in development, including the transition from elementary to middle school and the transition from high school to early adulthood.

Conclusion

Overall, the results of the current study demonstrate that asocial behavior with peers predicts later anxiety and depressive symptoms during the transition to high school, an important period of change during which social interactions and relationships are likely to play a particularly central role in adjustment (e.g., Barber & Olsen, 2004). However, the personality trait of conscientiousness seems to protect withdrawn adolescents against the increased risk of these emotional difficulties. While withdrawal from peer interaction has a strong direct relation to both anxiety and depressive symptoms, the self-regulatory abilities encompassed by conscientiousness seem to buffer withdrawn adolescents against a heightened risk of depressive symptoms during this time. This pattern suggests that one method for preventing depressive symptoms among socially withdrawn individuals may be to foster the development of behavioral and emotional regulation abilities. Importantly, these findings also suggest that withdrawn children are not a homogeneous group who all share similar attributes and levels of risk. Researchers have identified several characteristics that distinguish different subgroups of socially withdrawn children and relate to their risk of negative outcomes, including gender, family factors, motivations for withdrawal, and peer experiences like rejection and exclusion (see Rubin et al., 2009). The current findings further suggest that the individual personality traits and dispositions of withdrawn children also play an important role in withdrawn children’s risk of experiencing internalizing problems.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the children, parents, and teachers who participated in the study as well as Allison Buskirk-Cohen, Kathleen Dwyer, Erin Galloway, Jon Goldner, Sue Hartman, Amy Kennedy, Angel Kim, Sarrit Kovacs, Alison Levitch, Melissa Menzer, Wonjung Oh, Joshua Rubin, and Erin Shockey who assisted in data collection and input.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (MH58116) to Kenneth H. Rubin; and by the NICHD Training Program in Social Development (NIH T32 HD007542) awarded to the Department of Human Development and Quantitative Methodology at the University of Maryland, which supported Matthew G. Barstead.

Biographies

Kelly A. Smith is a PhD student in the Department of Human Development and Quantitative Methodology at the University of Maryland, College Park. Her research interests include the influence of individual characteristics on social and emotional outcomes for socially withdrawn children, the development of prosocial and socially competent behavior, and interventions to improve the quality of children’s relationships.

Matthew G. Barstead is a a PhD student in the Department of Human Development and Quantitative Methodology at the University of Maryland, College Park. His research interests include studying why it is some children and adolescents appear to struggle when faced with the task of interacting socially with peers using a neurodevelopmental framework.

Kenneth H. Rubin, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Human Development and Quantitative Methodology at the University of Maryland, College Park. He received his PhD in Child Development and Family Relationships from Pennsylvania State University. His research interests are focused on such topics as social, emotional, and personality development; social cognition; aggression; social withdrawal/behavioral inhibition/shyness; peer relationships and friendship; and parenting and parent-child relationships.

Footnotes

Author’s Contributions

KS conceived of the study, participated in its design, conceptualization, and the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript; MB participated in the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis, and helped to draft the manuscript; KR participated in the study design, conceptualization, and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland, College Park. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participating adolescents, and assent was obtained from all participants.

References

- Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4–18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaranelli C, Caprara GV, Rabasca A, Pastorelli C. A questionnaire for measuring the Big Five in late childhood. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34:645–664. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00051-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Olsen JA. Assessing the transitions to middle and high school. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19:3–30. doi: 10.1177/0743558403258113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley CE, Roesch SC. Coping with daily stress: The role of conscientiousness. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;50:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Graham S. The transition to high school as a developmental process among multiethnic urban youth. Child Development. 2009;80:356–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu OJ, Samuels JF, Costa PT, Reti IM, Eaton WW, Nestadt G. Anxiety and depressive disorders and the five‐factor model of personality: A higher‐and lower‐order personality trait investigation in a community sample. Depression and Anxiety. 2004;20:92–97. doi: 10.1002/da.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgett DJ, Oddi KB, Laake LM, Murdock KW, Bachmann MN. Integrating and differentiating aspects of self-regulation: Effortful control, executive functioning, and links to negative affectivity. Emotion. 2013;13:47–63. doi: 10.1037/a0029536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess KB, Wojslawowicz JC, Rubin KH, Rose-Krasnor L, Booth-LaForce C. Social information processing and coping styles of shy/withdrawn and aggressive Children: Does friendship matter? Child Development. 2006;77:371–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Roberts BW, Shiner RL. Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:453–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Shiner RL. Personality development. In: Damon W, Lerner R, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology, Vol 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 300–365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Compton RJ. Ability to disengage attention predicts negative affect. Cognition & Emotion. 2000;14:401–415. doi: 10.1080/026999300378897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Prakash K, O’Neil K, Armer M. Do you “want” to play? Distinguishing between conflicted shyness and social disinterest in early childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:244–258. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Rose-Krasnor L, Weeks Mj, Kingsbury A, Kingsbury M, Bullock A. Alone is a crowd: Social motivations, social withdrawal, and socioemotional functioning in later childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49:861–875. doi: 10.1037/a0028861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Karney BR, Hall TW, Bradbury TN. Depressive symptoms and marital satisfaction: within-subject associations and the moderating effects of gender and neuroticism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:557–570. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doey L, Coplan RJ, Kingsbury M. Bashful boys and coy girls: A review of gender differences in childhood shyness. Sex Roles. 2014;70:255–266. doi: 10.1007/s11199-013-0317-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Duckworth AL, Spinrad TL, Valiente C. Conscientiousness: Origins in childhood? Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:1331–1349. doi: 10.1037/a0030977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ. The biological basis of personality. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Findlay LC, Coplan RJ, Bowker A. Keeping it all inside: Shyness, internalizing coping strategies and socio-emotional adjustment in middle childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33:47–54. doi: 10.1177/0165025408098017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H, Ladd GW. Anxious solitude and peer exclusion: A diathesis–stress model of internalizing trajectories in childhood. Child Development. 2003;74:257–278. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H, Spangler T. Early childhood anxious solitude and subsequent peer relationships: Maternal and cognitive moderators. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:515–535. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JW, Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Mineka S, Rose RD, Waters AM, Sutton JM. Neuroticism as a common dimension in the internalizing disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:1125–1136. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock GR, Mueller RO. Rethinking construct reliability within latent variable systems. In: Cudeck R, du Toit S, Sörbom D, editors. Structural equation modeling: Present and future—A Festschrift in honor of Karl Jöreskog. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2001. pp. 195–216. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson JG, Williams PG. Neuroticism, daily hassles, and depressive symptoms: An examination of moderating and mediating effects. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:1367–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hymel S, Rubin KH, Rowden L, LeMare L. Children’s peer relationships: longitudinal prediction of internalizing and externalizing problems from middle to late childhood. Child Development. 1990;61:2004–2021. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb03582.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Isakson K, Jarvis P. The adjustment of adolescents during the transition into high school: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;28:1–26. doi: 10.1023/A:1021616407189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Campbell LA, Knack JM, Waldrip AM, Campbell SD. Do Big Five personality traits associated with self-control influence the regulation of anger and aggression? Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41:403–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Srivastava S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Timmons KA. Depression in its interpersonal context. In: Gotlib I, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:372–380. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra TA, Akse J, Hale WW, Raaijmakers QA, Meeus WH. Longitudinal associations between personality traits and problem behavior symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality. 2010;44:273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Gamez W, Schmidt F, Watson D. Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:768–821. doi: 10.1037/a0020327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health System; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kushner SC, Tackett JL, Bagby RM. The structure of internalizing disorders in middle childhood and evidence for personality correlates. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2012;34:22–34. doi: 10.1007/s10862-011-9263-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW. Peer rejection, aggressive or withdrawn behavior, and psychological maladjustment from ages 5 to 12: An examination of four predictive models. Child Development. 2006;77(4):822–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Bush NR, Long AC, Kovacs EA, Trancik AM. Effortful control as a moderator of the relation between contextual risk factors and growth in adjustment problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:509–528. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lianos PG. Parenting and social competence in school: The role of preadolescents’ personality traits. Journal of Adolescence. 2015;41:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, Schutte NS. The relationship between the five- factor model of personality and symptoms of clinical disorders: a meta-analysis. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2005;27:101–114. doi: 10.1007/s10862-005-5384-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, Blijlevens P. Self-reported reactive and regulative temperament in early adolescence: Relations to internalizing and externalizing problem behavior and “Big Three” personality factors. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:1035–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LJ, Padilla-Walker LM, Badger S, Barry CM, Carroll JS, Madsen SD. Associations between shyness and internalizing behaviors, externalizing behaviors, and relationships during emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:605–615. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9203-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LJ, Rubin KH, Fox NA. Social withdrawal, observed peer acceptance, and the development of self-perceptions in children ages 4 to 7 years. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2005;20:185–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2005.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman BM, Newman PR, Griffen S, O’Connor K, Spas J. The relationship of social support to depressive symptoms during the transition to high school. Adolescence. 2007;42:441–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Oldehinkel AJ, Brilman EI. The interplay and etiological continuity of neuroticism, difficulties and life events in the etiology of major and subsyndromal, first and recurrent depressive episodes in later life. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:885–891. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S, Vitaro F, Barker ED, Borge AI. The timing of Middle‐Childhood peer rejection and friendship: Linking early behavior to Early‐Adolescent adjustment. Child Development. 2007;78:1037–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior M, Smart D, Sanson A, Oberklaid F. Does shy-inhibited temperament in childhood lead to anxiety problems in adolescence? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:461–468. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2014. http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software. 2012;48:1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB. Social withdrawal and anxiety. In: Vasey MW, Dadds MR, editors. The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 407–434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Chen X, McDougall P, Bowker A, McKinnon J. The Waterloo Longitudinal Project: Predicting adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems from early and mid-childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:751–764. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400006829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan RJ. Paying attention to and not neglecting social withdrawal and social isolation. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2004;50:506–534. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2004.0036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, Bowker JC. Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:141–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Wojslawowicz JC, Rose-Krasnor L, Booth-LaForce C, Burgess KB. The best friendships of shy/withdrawn children: Prevalence, stability, and relationship quality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:139–153. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9017-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sable J, Hill J. Overview of public elementary and secondary students, staff, schools, school districts, revenues, and expenditures: School Year 2004–05 and Fiscal Year 2004 (NCES 2007-309) Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman LD, Ollendick TH. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: An integrative review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1:125–144. doi: 10.1023/A:1021887712873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SL, Rubin KH. The social problem-solving skills of anxious-withdrawn children. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7(02):323–336. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400006532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, McDonald KL, Rubin KH, Laursen B. Peer rejection as a social antecedent to rejection sensitivity in youth: The role of relational valuation. Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;53:939–942. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Gamez W, Simms LJ. Basic dimensions of temperament and their relation to anxiety and depression: A symptom-based perspective. Journal of Research in Personality. 2005;39:46–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2004.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller M, Vannatta K, Schafer J, Noll RB. Behavioral reputation: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:129–139. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]