To the Editor

Oral immunotherapy (OIT) can promote desensitization to food allergens, but minimizing, or lessening in severity, the high rate of adverse reactions is a clinical imperative.(1) The repetitive oral administration of allergens to atopic individuals mimics exposures thought to trigger eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Indeed, several cases of EoE occurring during OIT have been noted,(2,3) including during peanut OIT with omalizumab, a strategy intended to reduce side effects and to allow for faster desensitization.(4) Here, we describe two additional peanut-allergic subjects treated with omalizumab and OIT who developed symptoms, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) findings, and biopsies consistent with EoE that substantially improved after discontinuation of OIT, implicating the OIT food as the trigger. By describing these two cases in detail, we hope to add to the growing body of knowledge about the relationship between OIT and EoE, and also raise the possibility that omalizumab may have initially prevented or masked EoE in these two subjects.

This phase I/II study enrolled thirteen peanut-allergic patients aged 12-20 years with serum peanut-specific IgE >5 kU/L.(5) We excluded subjects with a history of severe anaphylaxis to peanut or omalizumab, moderate to severe asthma, poorly-controlled atopic dermatitis, or other serious underlying disease. Peanut OIT was begun with a two-day modified rush phase to a goal of 475 mg peanut protein, followed by a build-up phase, during which daily OIT doses were escalated biweekly by 20-33% to the target maintenance dose of 4000 mg daily peanut protein. Omalizumab administration (150-375 mg every 2-4 weeks or 0.015 mg/kg/kU-IgE/L) was begun four months before starting OIT and continued until subjects had been on maintenance dosing for one month. Typical length of omalizumab administration was 11 months, as most subjects achieved maintenance dosing after 6 months of OIT. The subjects described below had similar baseline peanut-specific IgE (PN-IgE), and skin-prick tests (SPT, performed with 1:20 peanut extract from Greer Laboratories, Lenoir, NC) when compared to other individuals in the trial. The total IgE (tIgE) for subject 2 was below the 25th percentile for individuals enrolled in this trial. Subject 1 had a baseline PN-IgE of 144 kU/L, tIgE of 504 kU/L, and 15.5 mm SPT; subject 2 had a baseline PN-IgE of 13.6, tIgE of 46.2, and a 17 mm SPT (median[IQR] for the group: PN-IgE 85.1 kU/L [10.4-171.5 kU/L], tIgE 328.5 kU/L [81.5-519.8 kU/L], SPT 13.5 mm [8.0-19.5 mm])

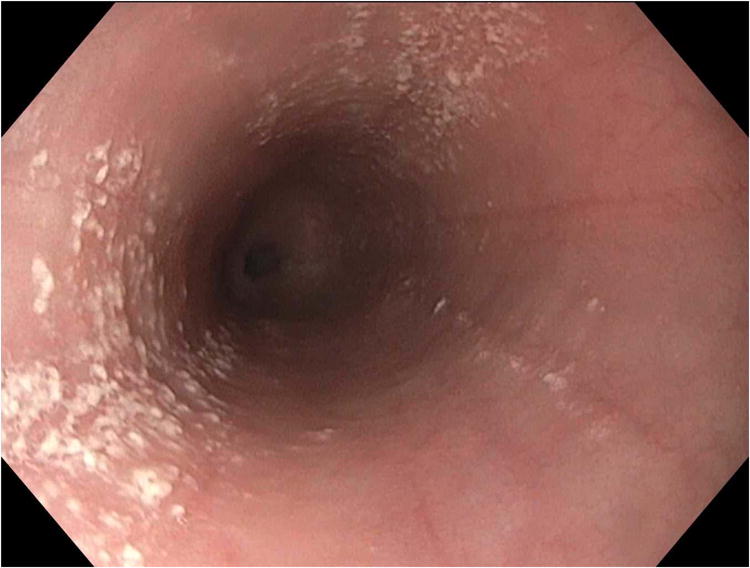

Subject 1 was a 17-year-old female with asthma, atopic dermatitis, and seasonal allergies. After eight months of OIT, one month into post-omalizumab maintenance dosing, she reported the development of dysphagia and heartburn, which were temporally unrelated to OIT dosing. She was referred to gastroenterology, and indicated, in retrospect, that she had mild, intermittent dysphagia beginning a year before starting OIT, and that her father had esophageal strictures requiring dilations every 2-3 years. Because of concern for EoE, OIT was stopped, an EGD several days later showed mucosal changes suggestive of EoE (Figure 1A), and esophageal biopsies demonstrated eosinophilia meeting EoE criteria (Table 1). To address whether her EoE was related to peanut exposure, we did not make additional changes besides stopping OIT and she did not undergo a trial with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) or treatment with topical steroids at that time.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic images from case 1. (A) Baseline endoscopy while still on peanut OIT shows longitudinal furrows, decreased vascularity, and white plaques/exudates. (B) Endoscopy after discontinuation of OIT has essentially normalized. (C) Endoscopy after a PPI trial with recurrent symptoms of dysphagia showing plaques, furrows, and decreased vascularity similar to the baseline exam.

Table 1.

Maximum eosinophil count (eosinophils per high power field; eos/hpf) and pathological findings in esophageal biopsies and endoscopic findings from the cases. Abbreviations: Increased intraepithelial eosinophils (IIE), eosinophilic microabscesses (EM), gastroesophageal junction (GEJ), basal layer hyperplasia (BLH)

| On OIT | Two months off OIT | Five months off OIT | Fifteen months off OIT, after two months PPI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject 1 | ||||

| Proximal | 501 | 9 | 0 | 43 |

| Distal | 100 | 162 | Not biopsied3 | 102 |

| Findings | IIE, EM, extensive reactive atypia | Focal IIE | IIE at GEJ only | IIE, EM, BLH, spongiosis, lamina propria fibrosis |

|

| ||||

| Subject 2 | ||||

| Proximal | 21 | 4 | ||

| Distal | 52 | 6 | ||

| Findings | IIE, BLH | IIE | ||

Diagnostic criteria for EoE = 15 eos/hpf;

72 eos/hpf focally at the GEJ area of residual plaques that were biopsied separately;

98 eos/hpf focally at the area of residual plaques at the GEJ

Within days, her dysphagia substantially improved. Two months later, a repeat EGD showed improvement of mucosal and histologic changes, except for mild persistent findings at the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) (Table 1). A third EGD performed five months off OIT showed further improvement (Figure 1B), but with persistent findings at the GEJ. Other biopsy sites were free of eosinophils. She was asymptomatic and was monitored clinically without additional treatment besides a peanut-free diet.

Eight months later, thirteen months after stopping OIT, the patient developed recurrent dysphagia. In the interim, she had no known peanut exposures, allergic reactions, or changes to her diet, environment, or medications. She was started on 20 mg omeprazole twice daily. An EGD performed after two months later showed characteristic mucosal changes (Figure 1C) and esophageal biopsies confirmed a diagnosis of EoE (Table 1). At that time, the patient was begun on topical steroid treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis and has been followed by gastroenterology for for the last two years.

Subject 2 was an 18 year-old male with asthma and seasonal allergies previously treated with subcutaneous immunotherapy. During the buildup phase, he reported to his local doctor heartburn that was worse with hot or spicy foods, and was clinically diagnosed with “reflux” and started on omeprazole. These symptoms occurred up to 12 hours after OIT dosing, and were thus felt to be unrelated. He recorded mild heartburn on 19 out of 594 (3%) daily diary cards and missed no doses, but this is likely an under-estimation of his overall symptoms, as the primary use of these cards were to record symptoms occurring within two hours of the OIT dose. After approximately six months of OIT, within 4-8 weeks after omalizumab was stopped, his symptoms worsened to include cough with eating, chest tightness, and a gradual 15 pound weight loss over the next year. An EGD was performed at an outside center after 1.5 years on OIT, and revealed mucosal changes including rings and longitudinal furrows and eosinophilia meeting EoE criteria (Table 1). OIT was discontinued; the subject became completely asymptomatic within two days and regained the lost weight over the next month. He was also able to discontinue omeprazole without recurrence of symptoms.

A repeat EGD two months post-OIT showed improvement of the previous mucosal changes, with only mild longitudinal furrows in the distal esophagus. Esophageal biopsies had also substantially improved (Table 1). The patient later acknowledged eating one Reese's Pieces® candy daily (estimated 40-70 mg peanut protein) in a self-initiated attempt to maintain desensitization after discontinuation of OIT, and was doing so at the time of endoscopy, which may have contributed to the mild eosinophilia in his follow-up biopsies. The patient was counseled to discontinue peanut ingestion and remains asymptomatic off OIT. He has been followed as an allergy clinic patient and has not reported recurrence of symptoms for the last three-and-a-half years. He has not undergone another EGD on a strictly peanut-free diet.

It remains unknown whether OIT-associated EoE is specifically caused by the OIT allergen, becomes unmasked during OIT, or develops concurrently. Here, we present the onset of symptomatic EoE during peanut OIT in two individuals pretreated with omalizumab. The rapid clinical improvement after cessation of peanut ingestion without other medical intervention, confirmed by substantial histologic improvement upon repeat EGD, strongly suggests that peanut was the EoE trigger. Subject 1's course is more complicated, with her history of intermittent mild dysphagia prior to beginning OIT and then subsequent flare over a year after discontinuing OIT. Subjects with multiple eosinophilic esophagitis food triggers have been previously reported,(6) and it is most likely that this subject had pre-existing but mild EoE, which flared with OIT, and then flared again with an as-yet unidentified trigger or other precipitating factor. It is also possible that her EoE worsened as a natural course and was not related to omalizumab withdrawal, though sequence of events strongly suggests the two were related.

Abdominal pain and dose aversion are commonly observed during OIT, and when symptoms are intolerable, the treatment is discontinued. In the vast majority of individuals, the symptoms resolve upon withdrawal. Because OIT research volunteers with gastrointestinal symptoms are rarely referred for endoscopy, OIT-associated EoE may be underestimated.

Notably, two additional subjects were withdrawn from this trial with gastrointestinal complaints without further evaluation. These subjects resolved clinically within days of cessation of OIT and have not alerted study staff with subsequent recrudescence of symptoms. Our research center also has in place a separate observational protocol that allows for essentially indefinite follow-up of subjects, to better assess the long-term sequelae of events occurring during or after the primary trial, we have not been alerted of any additional gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms in any of the other subjects previously enrolled in this trial of peanut OIT with omalizumab pretreatment.

It is also noteworthy that these cases tolerated months of progressively larger doses of peanut protein and did not develop gastrointestinal symptoms until maintenance dosing, much later than we have observed in other OIT studies (Virkud YV, unpublished data, 2016), possibly due to omalizumab pretreatment. Co-administration of anti-IgE monoclonal antibody has been studied as a strategy to reduce OIT side effects and permit accelerated dosing schedules.(4,7,8) However, in these two subjects, administration of omalizumab prior to and during OIT did not appear to protect subjects from EoE after withdrawal of the drug, similar to findings from a trial showing that omalizumab was not effective for treating EoE.(9) It remains possible that omalizumab did attenuate or mask early symptoms leading to a delay in onset and/or recognition. Additionally, the higher rate of EoE seen in this trial (2/13 or 15%) compared to 3% in previous reports of EoE with OIT (2) may be due to this delay in onset. Had these subjects not received omalizumab, they may have dropped out of the trial due to non-specific GI symptoms at lower doses of peanut protein without a GI evaluation, rather than with symptoms clearly warranting an evaluation for EoE at the high maintenance dose. This higher rate of EoE could also be due to the steep increase of the dosing regimen in this trial, though these subjects appeared to tolerate these increases until the cessation of omalizumab. Future studies could be performed comparing gastrointestinal side effects and rates of EoE in subjects treated with omalizumab to those not being treated.

The relationship between food immunotherapy, intolerable gastrointestinal side effects, and EoE deserves future study. Additionally, these two cases highlight the importance of educating potential OIT subjects about the risk of developing EoE while on this experimental therapy. Subjects enrolling in trials of OIT should be asked about gastrointestinal symptoms at baseline, which could be considered exclusionary when suggestive of pre-existing EoE. Consideration should be given to informed consent forms listing EoE or an EoE-like syndrome as a complication of OIT and subjects should be monitored for the development of symptoms consistent with EoE such as dysphagia and chest tightness in adults and adolescents; and abdominal pain, heartburn, vomiting, regurgitation in younger children. All subjects should be monitored for weight loss or poor growth. There should be a low threshold for starting an EoE evaluation, especially if symptoms are severe enough to cause subjects to drop out of trials.

Clinical Implications.

We describe two subjects enrolled in a trial of peanut oral immunotherapy (OIT) with omalizumab who developed eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Administration of omalizumab prior to and during OIT did not prevent the development EoE after withdrawal of the drug.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH awards 2R21-AI-094014-03, T35-DK007386 and departmental funds from the UNC Department of Pediatrics. Omalizumab supplied by Genentech.

We would like to thank Lynn Christie and Stacie Jones of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences for providing us with their food challenge protein equivalency tables for the estimation of the amount of peanut protein in a Reese's Piece® and Ping Ye and Kelly Orgel of the University of North Carolina for compiling data from this trial for use in this communication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sampson HA. Peanut oral immunotherapy: is it ready for clinical practice? J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013 Jan;1(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucendo AJ, Arias A, Tenias JM. Relation between eosinophilic esophagitis and oral immunotherapy for food allergy: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014 Dec;113(6):624–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Semancik E, Sayej W. Oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy induces eosinophilic esophagitis: three pediatric case reports. Pediatric Allergy Immunol. 2016 Aug;27(5):539–41. doi: 10.1111/pai.12554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacGinnitie AJ, Rachid R, Gragg H, Little SV, Lakin P, Cianferoni A, et al. Omalizumab facilitates rapid oral desensitization for peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Sep 5; doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.010. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peanut Oral Immunotherapy and Anti-Immunoglobulin E (IgE) for Peanut Allergy. [Accessed May 3, 2015]; Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00932282.

- 6.Lucendo AJ, Arias Á, González-Cervera J, Yagüe-Compadre JL, Guagnozzi D, Angueira T, et al. Empiric 6-food elimination diet induced and maintained prolonged remission in patients with adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a prospective study on the food cause of the disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 Mar;131(3):797–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nadeau KC, Schneider LC, Hoyte L, Borras I, Umetsu DT. Rapid oral desensitization in combination with omalizumab therapy in patients with cow's milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Jun;127(6):1622–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood RA, Kim JS, Lindblad R, Nadeau K, Henning, AK, Dawson P, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of omalizumab combined with oral immunotherapy for the treatment of cow's milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Apr;137(4):1103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clayton F, Fang JC, Gleich GJ, Lucendo AJ, Olalla JM, Vinson LA, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults is associated with IgG4 and not mediated by IgE. Gastroenterology. 2014 Sep;147(3):602–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]