Abstract

We studied a mango glutathione S-transferase (GST) (Mangifera indica) bound to glutathione (GSH) and S-hexyl glutathione (GSX). This GST Tau class (MiGSTU) had a molecular mass of 25.5 kDa. MiGSTU Michaelis-Menten kinetic constants were determined for their substrates obtaining a Km, Vmax and kcat for CDNB of 0.792 mM, 80.58 mM·min−1 and 68.49 s−1 respectively and 0.693 mM, 105.32 mM·min−1 and 89.57 s−1, for reduced GSH respectively. MiGSTU had a micromolar affinity towards GSH (5.2 μM) or GSX (7.8 μM). The crystal structure of the MiGSTU in apo or bound to GSH or GSX generated a model that explains the thermodynamic signatures of binding and showed the importance of enthalpic-entropic compensation in ligand binding to Tau-class GST enzymes.

Keywords: Glutathione S-transferase, Tau class, mango, Mangifera indica, glutathione, S-hexyl glutathione, detoxification, crystal structure, isothermal titration calorimetry

1. INTRODUCTION

Glutathione S-transferases (GST, EC 2.5.1.18) are a heterogeneous group of cell detoxifying enzymes, which catalyze the reduced glutathione (GSH) conjugation with hydrophobic compounds containing an electrophilic atom [1, 2]. These electrophiles include both endogenous and xenobiotics compounds, which are targeted at specific sites either intra or extracellular [3–7]. The GSTs are ubiquitous proteins, mainly cytosolic, classified into different classes [8–10]. The theta, zeta, phi and tau GST classes have been reported mainly in plants, being phi and tau classes the most abundant between them [3, 10–12]. The GST family has multiple functions in plants besides herbicide resistance and xenobiotic detoxification; they can be induced by pathogens or dehydration, and may even bind auxins and anthocyanin [13] [7, 14, 15]. Other roles postulated for GSTs are as part of stress responses towards heavy metals, drought, salt and ozone [7, 14, 15].

All three-dimensional structures of GST known to date have a similar fold despite the low overall identity amongst the sequences of different GST classes. The GSTs are homodimers of about 50 kDa, where each monomer consists of a thioredoxin-folded N-terminal domain and an α-helical C-terminal domain connected by a linker loop region [16]. The catalytic cavity has two ligands binding sites per subunit, the glutathione-binding site (G-site) located in the N-terminal domain, and the hydrophobic xenobiotic binding site (H-site) located in the C-terminal domain [14]. The N-terminal domain is somewhat conserved and contains the specific residues that are critical for catalytic activity and binding GSH, mostly by hydrogen bonds. The catalytic residue in GST is tyrosine, cysteine or a serine, as occurs in Tau-class. These residues favor deprotonation of GSH to form a reactive thiolate anion [1].

GSTs can utilize a variety of substrates, due to the variability of its C-terminal domain. The enzyme conjugates activated GSH with almost any hydrophobic compound containing an electrophilic atom. The hydrophobic substrate binding site (H-site) is a pocket that mainly consists of non-polar side chains that provide favorable interactions with the xenobiotics [14].

The variability in H-site leads to a diversity of substrates that can be conjugated with GSH: arene oxides, organic halides, epoxides, α,β-unsaturated carbonyls, organic thiocyanates and esters [1, 17]. The G-site is conserved in the many GST crystal structures determined to date [17], being the H-site where the sequence is less conserved; therefore, structural information of this site is more useful. GSX is an excellent ligand for crystallographic and thermodynamic studies since it occupies both G- and H-site, does not react with GST and allows structural comparison across classes and species. Among over 316 GSTs reported at the PDB (Protein Data Bank), only forty belong to plants, and their amino acid sequence share a total of a 10% identity [18].

Besides basic knowledge, the study of structure and function of GSTs is also important for applications as a biocatalyst in green chemistry applications [19] and directed evolution has been applied towards obtaining better GST catalysts [20].

This work reports three mango GST Tau-class crystallographic structures in apo (unliganded), glutathione (GSH) and S-hexyl-glutathione (GSX)-bound, these results are correlated with binding thermodynamics and enzyme kinetics.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Chemical and biochemical reagents

GSH, CDNB, GSX, biochemical reagents and culture media were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Synthetic gene synthesis and cloning services were provided by DNA2.0.

2.2 Recombinant expression and purification

A GST coding sequence (GenBank KX061499) was cloned from mango (cv. Haden) mesocarp and classified as Tau class through BLAST analysis by sequence comparison with the GenBank non-redundant database. Amino acid sequence alignments were done with ClustalW and phylogenetic trees were done using the neighbor-joining method and bootstrapping using 1,000 replicates, as implemented in Geneious R8 (Biomatters, Ltd.) The amino acid sequence of MiGSTU was used to generate a codon-optimized E. coli DNA sequence that was synthesized and cloned into the T5-ampR-vector pJExpress404 (DNA 2.0) for recombinant over-expression.

The E. coli BL21(DE3) bacteria transformed with the pJExpress404-MiGSTU construct were grown in LB broth containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin, and induced with 1 mM IPTG for 6 h at 37°C. After centrifugation (7000 × g, 15 min, 4ºC), bacteria were lysed by sonication in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8, 1 mM PMSF and 100 μg/mL lysozyme) in a ratio of 4 mL of buffer per g of pellet. After centrifugation (32000 × g, 30 min, 4ºC), 1 % streptomycin was added to precipitate nucleic acids. The ammonium sulfate 50% saturation supernatant was extensively dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 buffer and then loaded into a Hi-Trap Q Sepharose HP (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, USA) chromatographic column. Protein eluted with a NaCl gradient was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and assayed for GSH-conjugation activity toward CDNB as described below. Purity was confirmed by silver-stained SDS-PAGE.

2.3 Enzyme activity

Recombinant MiGSTU was assayed for GSH conjugating activity using a spectrophotometric assay [21]. Conjugation of CDNB with GSH was measured recording the change in absorbance for 2 min at 340 nm, in a Cary 50 Bio UV-visible spectrophotometer (Varian, Mexico) at 25°C. The reaction mixture in a final volume of 1 mL contained 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5 and 1 mM each of GSH and CDNB. Reaction rates in the absence of substrates were recorded but their results were negligible. The GST activity was calculated using the molar ε=9600 M−1cm−1 of conjugated GSH. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

2.4 Quaternary structure determination

The oligomerization state of MiGSTU was analyzed by size-exclusion chromatography performed using a Superdex 75 HR10/300 GL gel filtration column (GE Healthcare). The column was previously calibrated with different size molecular mass markers, in a buffer containing 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 and 150 mM NaCl, in an ÄKTA pure chromatography system (GE Healthcare).

2.5 Kinetic characterization

Steady-state kinetic measurements for MiGSTU were performed at 25°C in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, as previously described [22]. Initial rates were determined in a 0.02 to 2.5 mM concentration range for each GSH and CDNB substrates, varying the concentration in one of them and keeping constant the other. The kinetic constants kcat and KM were determined by fitting the observed steady-state data to the Michaelis–Menten equation throughout the nonlinear regression analysis using Prism 3.02 (GraphPad Software Inc.). Turnover number was calculated based on one active site/subunit.

2.6 Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

Titration experiments were conducted in a VP-ITC calorimeter (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) at 25 °C. Briefly, solutions of MiGSTU at 1 mg/mL were dialyzed thoroughly with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8.0 and titrated with 0.8 mM GSH or 1 mM GSX in separate experiments. Protein and ligands were dissolved in the same buffer from the final dialysis. Raw calorimetric data were corrected for ligand dilution. The binding parameters Kd, ΔH and N were directly obtained by fitting the titration curves to two sequential binding sites model with the Origin 7 ITC analysis software from Microcal. From these values, ΔG and ΔS were also calculated.

2.7 Protein Crystallization

The MiGSTU purified protein was extensively dialyzed against 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 and concentrated to 15 mg/mL for crystallization trials. Crystallization conditions were obtained in the micro batch method and using Greiner plates (BioOne) for the apo MiGSTU, with 0.2 M ammonium acetate, 0.1 M bis-Tris pH 6.5, 25% w/v polyethylene glycol 3350. The hanging drop method was performed to obtain crystals of MiGSTU (15 mg/mL) with GSH and GSX incorporated in the crystallization solution. The plates were incubated at 16°C and the crystals grew after 4 weeks. Typical crystals were rhombohedral shaped, on average dimensions of 0.4 × 0.2 × 0.2 mm.

2.8 Data collection and processing

Apo- and GSH-MiGSTU crystals were diffracted in a Bruker D8 QUEST single-crystal X-ray diffractometer equipped with a CMOS detector, an Incoatec μS CuKα microfocus (λ=1.542 Å) with Helios MX optics and a kappa geometry goniometer. Crystals were soaked into a cryoprotectant made with mother liquor plus 20% PEG 400 and flash-cooled at 100 K for data collection with a cold nitrogen stream. The data was indexed, merged and scaled with the PROTEUM2 Bruker software suite. A MiGSTU crystal in complex with GSX were diffracted at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) on Beamline 14-1 (λ=1.181 Å) and data was reduced and processed with HKL2000 [23].

Structural phases were estimated by molecular replacement using CCP4 [24] using as a template a theoretical model of MiGSTU built with MOE (ChemComp) and based on wheat GST coordinates (PDB 1GWC) [25]. Refinement was done with PHENIX [26] and manual building and ligand positioning was done with COOT [27], using 2Fo-Fc map at 1.5 σ and omit maps elaborated in PHENIX. Structures were validated with MolProbity [28] and fulfilled quality parameters for deposition at the Protein Data Bank. Figures were elaborated with CCP4mg [29]. Ligand-protein interaction diagrams were generated using the LigPlot program in Windows, available at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/software/LigPlus/) [30, 31]. Dimer interfaces were calculated with PISA server (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/prot_int/pistart.html) [32].

3. RESULTS

3.1 MiGSTU primary structure analysis

The cloned MiGSTU open reading frame size is 690 nucleotides long and encodes for a protein of 229 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 25.5 kDa. The MiGSTU deduced amino acid sequence showed a maximum identity value of 77% with Citrus sinensis Tau-class GST [33] (Figure 1A).

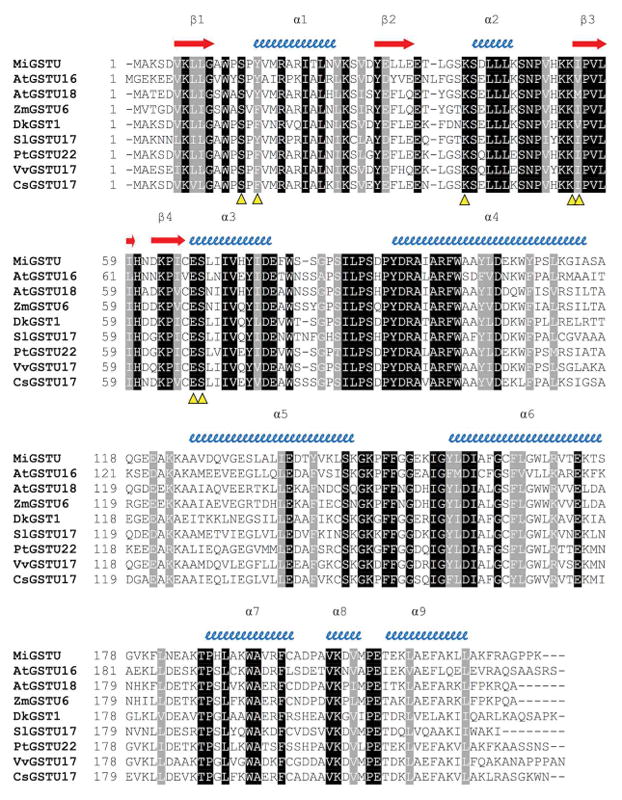

Figure 1.

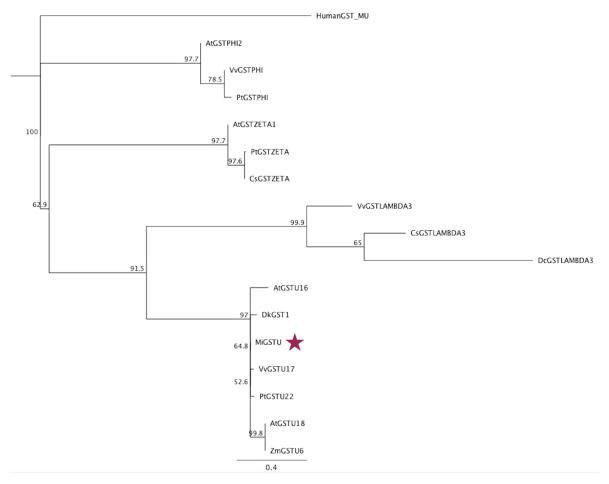

(A) Amino acid sequence alignment of mango GSTU with representative plant tau GSTs. Conserved residues in all plant Tau GSTs are shaded in black and conserved replaces in gray. Alpha helices and beta strands are represented as blue helices and red arrows, respectively. Predicted G-site residues of MiGSTU (KX061499) are marked with a yellow Δ. AtGSTU18, Arabidopsis thaliana (AEE28570.1); AtGSTU16, Arabidopsis thaliana (AEE33605.1); ZMGSTU6, Zea mays (NP_001147035.1); DkGSTU1, Diospyros kaki, (BAI40146.1); SlGSTU17, Solanum lycopersicum (XP_010320649.1); PtGSTU22, Populus trichocarpa (ADB11320.1); VvGSTU17, Vitis vinifera (XP_002273830); CsGSTU17, Citrus sinensis (XP_006483268.1). (B) Neighbor-Joining consensus tree phylogenetic tree built. In addition to the sequences mentioned in (A), the following sequences were included: AtGSTPHI2, Arabidopsis thaliana (NP_192161); VvGSTPHI, Vitis vinifera (XP_002262604); PtGSTPHI, Populus trichocarpa (XP_006386754); AtGSTZETA1, Arabidopsis thaliana (NP_178344); PtGSTZETA Populus trichocarpa (XP_006385118); CsGSTZETA Citrus sinensis (XP_006470782); VvGSTLAMBDA3 Vitis vinifera (XP_002281575); CsGSTLAMBDA3, Citrus sinensis (XP_006485968); DcGSTLAMBDA3 Daucus carota subsp. sativus (XP_017253337). The human GST Mu class amino acid sequence was used as an outgroup (NP_000552.2). The MiGSTU sequence is indicated with a red star.

Regions corresponding to both the G-site and H-site were identified in MiGST primary structure. As expected, the G-site is localized at the N-terminal domain between residues 14 and 69, and the H-site at the C-terminal domain between residues 106 and 220, being highly conserved within other GSTs of the same class (Figure 1, panel A). Several regions most commonly conserved in the Tau class GSTs have been previously reported, which may become functionally relevant [34]. The HKK motif was conserved in the MiGSTU (residues 52–54), likewise F151 and G157; meanwhile, the HNG domain corresponded to HND (60–62) in mango GST. Other highly conserved residues within this class were CES (65–67), R18 and D103 [35–37], which were also present in MiGSTU.

With regards to similarity to other plant GSTs, MiGSTU is very close to Vitis vinifera GST Tau class. Recently, mango amino acid sequences obtained by transcriptomics were found mostly similar to orange and grapes [38]. A phylogenetic analysis including MiGSTU (Figure 1B) revealed that the resulting clades resemble an early reported GST phylogenetic analysis [39], where Phi-class is the most distant from Tau class followed by the Zeta-class. Our analysis includes the novel Lambda class that appears to respond to salinity and also has the ligandin activity [40].

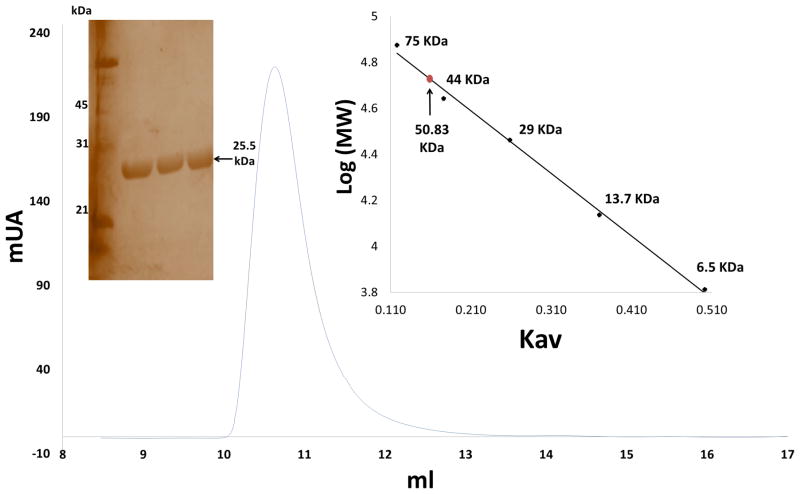

Recombinant MiGSTU was produced and purified from E. coli, its purity was confirmed by silver-stained SDS-PAGE (Figure 2). The yield was 10 mg of MiGSTU per liter of bacterial culture. The quaternary structure corresponds to a dimer with molecular mass of 50.83 kDa (Figure 2). The specific activity of the recombinant MiGSTU toward the CDNB substrate was 43.76 mmol min−1 per mg of protein.

Figure 2.

Gel filtration. The chromatogram obtained in the gel permeation chromatography shown after injecting MiGSTU in the X-axis have the volume in milliliters on the Y-axis have protein concentration (by absorbance at 280 nm) represented in milli absorbance units mAU; MiGSTU eluted at 10.63 ml, corresponding to molecular weight of the dimer. Calibration curve of logarithm of molecular mass (Log MW) versus partition coefficient (Kav), using the molecular mass of commercial standards; Conalbumine (75 kDa), Ovoalbumine (44 kDa), Anhidrase carbonic (29 kDa), Ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa) and Aprotinine (6.5 kDa). Kav of MiGSTU was 0.167 so that the molecular mass is 50.83 kDa.

3.2 Kinetic properties

A steady-state kinetic analysis for GSH and CDNB showed a Michaelis-Menten kinetics behavior (Supp. Material S.1) and kcat and KM parameters were determined (Table 1). A lower KM value for GSH than the KM for CDNB was obtained by the kinetic analysis. The affinity for GSH and CDNB of other GSTs from different sources could vary even for different GST isoforms in the same species, because of gene duplication and divergent evolution [35, 41].

Table 1.

Steady-state kinetic parameters of the recombinant MiGSTU and other GSTs from plants, using GSH and CDNB as substrate. The MiGSTU values shown are means calculated from three replicates.

| Enzyme | GSH | CDNB | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Km (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (mM−1 s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (mM−1 s−1) | ||

| MiGSTU | 0.693 | 89.52 | 129 | 0.7918 | 68.49 | 86.51 | This work |

| GmGSTU4-4 | 0.159 | 6.05 | 38 | 0.158 | 2.48 | 15.7 | Axarli et al., 2009 |

| GmGSTU10-10 | 0.0679 | 2.65 | 39 | 0.280 | NR | 9.5 | Skopelitou et al., 2015 |

| ZmGSTU1 | 0.56 | NR | NR | 1.010 | NR | 18.4×106 | Dixon et al., 2003 |

| ZmGSTU2 | 1.72 | NR | NR | 0.115 | NR | 30×107 | Dixon et al., 2003 |

| PtGSTU22 | 0.56 | 118.39 | 1997.12 | 1.72 | 574.6 | 334.07 | Lan et al., 2009 |

| PvGSTU2-2 | 0.049 | 10.84 | 6.6 | 0.864 | 21.2 | 24.75 | Chronopoulou et al., 2012 |

| PvGSTU1-1 | 0.1673 | 0.08396 | 2.58 | ND | ND | ND | Chronopoulou et al., 2012 |

| CsGSTU1 | 0.5 | 13.8×10−3 | 27.7×103 | 0.75 | 23.8×10−3 | 31.7×103 | Lo Piero et al., 2010 |

| CsGSTU2 | 0.5 | 76.9×10−3 | 153.8×103 | 1.0 | 108.1×10−3 | 108.1×103 | Lo Piero et al., 2010 |

ND: Not determined

NR: Not reported

The GST kcat value was 89.52 s−1 for the GSH substrate, compared to 68.49 s−1 for CDNB, revealing a slightly faster processing for GSH, which is consistent with those reported in other kinetic studies (Table 1). This is also reflected in the catalytic efficiency ratios (kcat/KM), obtaining a higher catalytic efficiency for the GSH substrate with 129 mM −1 s−1, compared to 86.52 mM−1 s−1 for CDNB.

3.3 GST binding thermodynamics

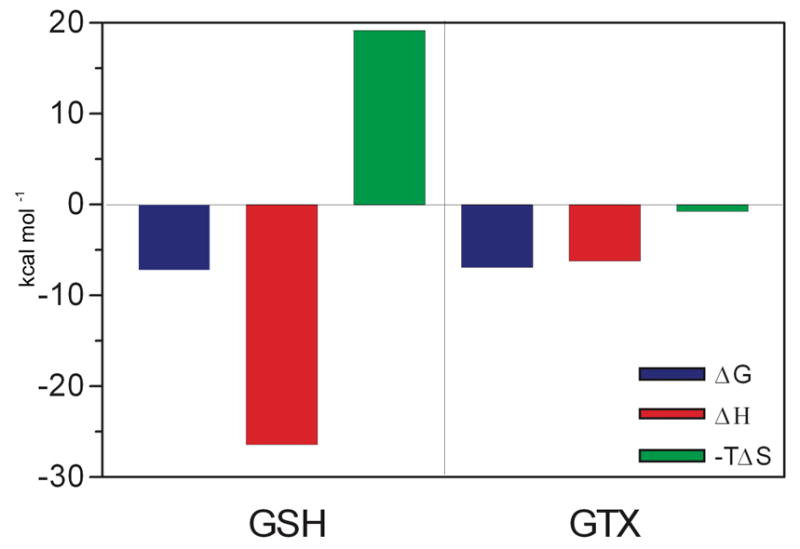

Besides affinity, ITC led us to the identification of significant energetic differences between the binding of both ligands. Binding of GSH and GSX to MiGSTU was exothermic (Table 2, Supp. Mat. S.2). GSH binding had a large unfavorable entropic component (-TΔS = 19.2 kcal mol−1) that was compensated by a large favorable enthalpic change (ΔH = −26.4 kcal mol−1). The Kd for GSH was 5.2 μM, which is similar to the affinity values reported for other GSTs [42, 43]. For GSX binding, the process was exothermic as well (Figure 3), and directed by a favorable enthalphic change (ΔH) of −6.7 kcal mol−1 and almost no entropic component (-TΔS = 0.4 kcal mol−1), leading to a Kd of 7.8 μM. GSX is a molecule similar to the product, which is a conjugated glutathione with an aliphatic xenobiotic.

Table 2.

Thermodynamics parameters for binding of GST

| Kd (μM) | ΔG (kcal mol−1) | ΔH (kcal mol−1) | -TΔS (kcal mol−1) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiGSTU-GSH | 5.2 | −7.2 | −26.4 | 19.2 | This work |

| MiGSTU-GSX | 7.8 | −6.9 | −6.2 | −0.71 | This work |

| Human GST P1-1-GSH | 5.9 | −5.5 | −11.2 | 5.7 | [1] |

| Human GST P1-1-GSX | 1.2 | −8.0 | −16.3 | 8.0 | [1] |

| Schistosoma japonicum GST-GSH | 0.99* | −4.9 | −5.7 | −0.8 | [2] |

| A. thaliana GST-GSX | 22.7 | −26.1* | −5.2 | −20.9* | [3] |

These values were calculated, as they are not shown in reference.

Figure 3.

Binding of MiGSTU to GSH and GSX for isothermal titration calorimetry.

Enzymes that utilize hydrophobic substrate keep their binding sites hidden from the bulk solvent. Occupation of the G-site by GSH is driven by a large favorable negative enthalpic change that compensates an unfavorable entropic component. The addition of the aliphatic chain appears to compensate this entropic component, since–TΔS is near to zero. These results will be later compared to the crystal structures to verify the structural nature of ligand binding.

3.4 Crystallographic structures of MiGSTU

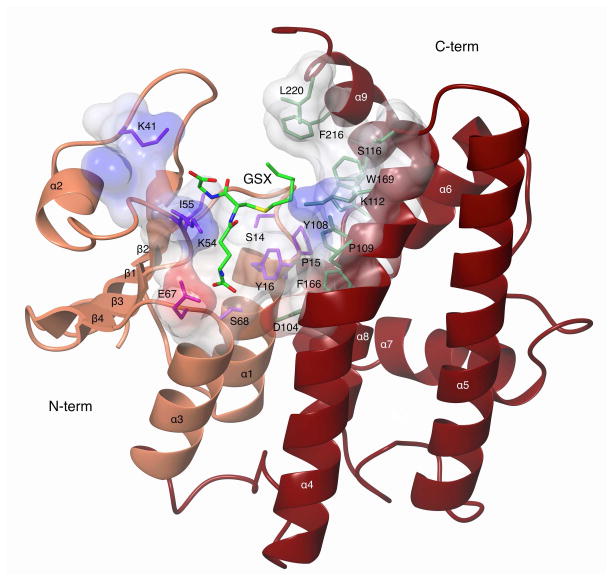

The MiGSTU crystals were obtained in the apo and holo form bound to GSH or GSX. Both MiGSTU apo and GSH-bound crystal structures were monoclinic, and contained a monomer in the asymmetric unit. Therefore, and because the unit cell parameter obtained, the biological unit was obtained by two-fold axis crystallographic symmetry from the C2 space group. GSX-MiGSTU complex was orthorhombic in the P212121 space group containing a dimer in the asymmetric unit. Final crystallographic statistics are presented in Table 3 and coordinates were deposited in the Protein Data Bank. The topology presented by MiGSTU is, in general, an N-terminal domain with a thioredoxin-like fold (residues 1–78) that contains the GSH-binding site (G-site) and a C-terminal globular domain (residues 90–219) that contains the hydrophobic substrate binding site (H-site) as shown in Figure 4.

Table 3.

X-ray data collection and refinement statistics. Values in parentheses are for the last resolution shell.

| Parameters | Apo-MiGSTU | GSH-MiGSTU | GSX-MiGSTU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection statistics | |||

| Space group | C121 | C121 | P212121 |

| Unit-cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 88.2 49.4 53.3 | 87.5 48.2 52.7 | 64.3 88.8 96.6 |

| α, β, γ angles (degrees) | 90.0, 103.2, 90.0 | 90.0, 104.2, 90.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 22.3–1.80 (1.86–1.80) | 20.3–2.30 (2.38–2.30) | 40.3–2.35 (2.48–2.35) |

| No. of reflections | 404742 | 18448 | 346557 |

| No. of unique reflections | 20863 (2090) | 9224 (954) | 23652 (3425) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (100.0) | 96.30 (97.6) | 100.0 (100.0) |

| Rmerge (%) | 32.8 (45.6) | 4.3 (29.9) | 17.7 (111.3) |

| CC1/2 (%) | 97.5 (90.6) | 99.8 (82.1) | 99.7 (86.8) |

| I/σ(I) | 28.0 (16.8) | 25.0 (4.3) | 11.8 (3.3) |

| Multiplicity | 19.4 (11.9) | 2.0 (2.0) | 14.6 (14.7) |

| Monomers per asymmetric unit | 1 | 1 | 2 |

|

| |||

| Refinement statistics | |||

| Resolution range (Å) | 22.3–1.80 | 20.3–2.30 | 40.3–2.35 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 16.1/18.9 | 19.3/24.3 | 18.8/22.6 |

| No. of atoms | |||

| Protein | 1792 | 1726 | 3502 |

| Ligand | 25 | 48 | 94 |

| Water | 408 | 52 | 124 |

| Mean B-values (Å2) | |||

| Protein | 11.6 | 28.6 | 43.4 |

| Ligand | 19.0 | 33.1 | 43.6 |

| Water | 23.9 | 28.8 | 45.6 |

| All atoms | 13.9 | 28.7 | 43.9 |

| Wilson plot | 10.0 | 20.2 | 36.3 |

| RMSD from ideal stereochemistry | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Bond angles (degrees) | 1.23 | 1.04 | 1.22 |

| Coordinate error (Maximum-Likelihood Base) | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.21 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |||

| Most favored regions | 98.7 | 96.8 | 97.0 |

| Additional allowed regions | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| Disallowed regions | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

| PDB code | 5G5E | 5G5F | 5KEJ |

Figure 4.

Ribbon representation of a MiGSTU monomer. The N-terminus is shown in coral and the C-terminal domain in tan. The G and H-site side chains are shown in surface and sticks representation. GSX bound in the active site is shown in green sticks.

All structures were compared and the root mean square deviation (RMSD) was calculated using a Gaussian-weighting model [44] in MOE [45] (Supp. Mat. S.3). To our knowledge, this is the first time a structural and thermodynamical comparative study is made between an unligated, GSH and GSX-bound Tau-class GST. The RMSD between free and bound monomers was 0.40 Å for a Mu-class GST [46] whereas for MiGSTU was 0.99 Å (Supp. Mat. S.3). The three structures superimposed permit identification of three loops with large structural changes. The main change is located in the loop between α5 and α6 at the C-terminal domain of the structure and does not form part of the H-site, followed by α1-β2 that is part of the G-site and contacts the glycyl group from GSH. Finally, loop α6-α7 is the less flexible and reflects a shift of helix α6 towards the H-site in the MiGSTU-GSX structure (Supp. Mat. S.3). The position of GSX and GSH almost superimpose, with exception of the aliphatic C6 hexyl chain towards the H-site.

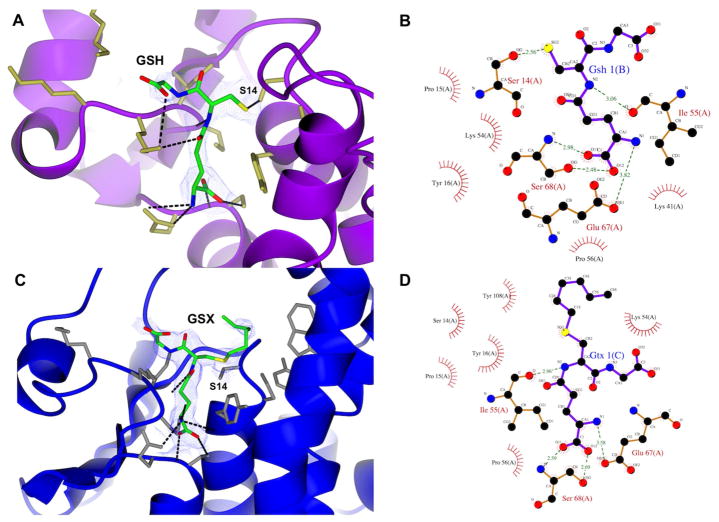

3.5 Ligand binding to MiGSTU

The GSH-binding site is conserved among GSTs to provide an adequate environment for sulfur activation and nucleophilic attack to substrates [1]. Electron density supported the modeling of GSH and GSX into the G-site (Figure 5A and 5C). Overall ligand binding is conserved in both structures. Tau GSTs have a serine as their catalytic residue [47] and MiGSTU S14 makes a 2.6 Å-hydrogen bond with the sulfur atom of GSH, with good electron density supporting this contact. A nearby Y16 has van der Waals contact with GSH or GSX cysteinyl portion; this is consistent with the observed in others GSTs [1, 48]. The cysteine amino group from GSH also makes a hydrogen bond with the main-chain of I55. GSH-α-glutamate makes hydrogen bonds with E67 and S68 and a hydrophobic contact between Y16 and the GSH-aliphatic chain (Figure 5B). The GSH-glycine residue is more flexible and makes a hydrogen bond with K41. Similar contacts are found in other Tau-GST structures with GSH or GSX bound [49]. It is also remarkable that catalytic S14 is flanked by prolines (P13 and P15) and this feature is also shared with maize Tau-class GST (PDB 1GWC).

Figure 5.

Modeling of GSH and GSX into the G-site. (A) GSH with electronic density in G-Site. (B) Ligplot diagram of GSH in G-Site. (C) GSX with electronic density in G-Site. (D) Ligplot diagram of GSX in G-Site.

The α-glutamyl portion from GSH or GSX makes similar hydrogen bonds with S68 backbone and side-chain hydroxyl and an ionic bond between E67 carboxyl and the alfa-amino (Fig., 5B and 5D). I55 makes a hydrogen bond with N-cysteinyl of GSH or GSX and the glycyl portion is exposed to the solvent, making no specific contacts to the G-site

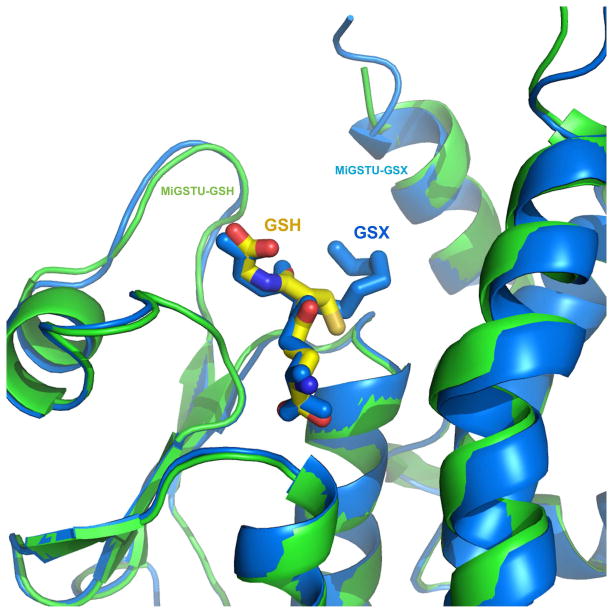

Hexyl from GSX makes hydrophobic contacts with K41, Y108, W169 and Y216. GSX binding has been measured by Trp quenching in S. japonicus [42] and this is consistent with the proximity of W169 to the aliphatic chain. The GSH and GSX ligands, both are located on the G-site, are superposed on the same place and hexyl group stands in GSX (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Superposition of MiGSTU with GSH (structure in green and GSH in yellow) versus MiGSTU with GSH (structure in blue and GSX in blue).

4. DISCUSSION

The first approach to this enzyme study and the understanding of its function has been carried out through the analysis of its primary sequence. Even though conserved domains prevail among different GST classes, such as the thioredoxin domain at the N-terminal, the C-terminal domain which binds the electrophilic substrates (as xenobiotics) is more variable among and within classes [50, 51]. This variability could be related to the ability to combine the binding of a variety of xenobiotic compounds with different structures [1]. A serine residue that is highly conserved at the plant Tau, Theta and Zeta classes, prevails at the GSH binding domain [37]. Such residue that is present at the MiGSTU as S14 is postulated as the catalytic residue responsible for stabilizing the GSH thiolate anion bound to the enzyme [52]. In the binary complex with GSH, a bond is found between S14 and GSH-thiol is observed. GSH cysteinyl is substituted with the aliphatic hexyl that inserts into the H-site.

Affinity and specificity towards their hydrophobic substrates vary among GST families. The Tau and Phi classes, which are mainly found in plants, are highly specificity towards CDNB, which is considered as the model substrate. The MiGSTU revealed a high activity value for this substrate compared to GSTs from other plants, suggesting that it may also work in exogenous compounds detoxification. A wide variability in catalytic properties has been previously reported when studying the divergence of such family genes in Populus trichocarpa [53] and the moss Physchomitrella patens [54], even among isoenzymes from the same class. Moreover, differences in specific activity, using CDNB as a substrate, were reported in sweet orange Tau class GST isoforms [33], being the GSTU2 three times more active than those of the GSTU1, which was also shown in their catalytic properties.

These enzymes mainly revealed a higher affinity to GSH rather than to the electrophilic substrate, which can be appreciated in lower KM values for GSH, as observed for MiGSTU; this is consistent with the highly conserved GSTs N-terminal domain. The higher affinity towards a substrate affect the more efficient use of it, as well as the further processing into the product, which in the case of catalytic efficiencies (kcat/KM) for GSTs, a greater efficiency is seen in the use of GSH compared with the electrophile [1, 55]. The GSTs, in addition to the isoenzymes ability to use different substrates, use different catalytic mechanisms, causing a greater diversity in the catalytic constants of this enzyme family.

Although random, ping-pong and sequential mechanisms have been reported for the GST enzyme family, the ordered binding of substrates seems to prevail. Even though some exceptions have been found within this family, a Michaelis-Menten behavior has been revealed by most of the GSTs. Differences in two enzymes catalytic mechanisms of the same class (Tau) were reported in Phaseolus vulgaris [3], where a Michaelis–Menten kinetics was followed by the PvGSTU2-2 using CDNB as the substrate, while a sigmoid substrate dependence was revealed by the PvGSTU1-1. A rapid equilibrium random sequential bi-bi mechanism [35, 56], has been reported in the GSTs from other plants, such as sorghum, as well as in three tomato GSTUs [57]. The MiGSTU showed a Michaelis-Menten kinetics, and a bi-bi mechanism type that could be sequential (ordered) is suggested, in accordance to that reported for other GSTs [3, 35, 57]. Since the kinetic mechanism is related to the enzyme structure, in the ordered mechanism the binding of the first substrate to the active site induces a conformational change, needed for the binding of the second substrate. A conformational change takes place upon the binding of the GSH substrate to the active site at the G-site in GSTs. This is revealed in the MiGSTU crystallographic structure and many others, and it seems to be a requirement for the proper formation of the H-site. By overlaying the crystallographic structure Apo of MiGSTU against the structure with GSH, we found an RMSD of 0.99 Å calculated by MOE. The main difference between all structures is helices 4 and 5 together with the loop that links the region with more changes in their side chains. This is in accordance to the thermodynamic signature of GSH binding, which showed large enthalpy and entropy changes that could be related to active site interactions. It is assumed that the cytosolic GSTs broad substrate specificity correlates with a structural flexibility, which allows the different electrophilic substrate structures recognition with a minimum energy cost [58].

The observed thermodynamic values may arise from the binding mode of GSH to the MiGSTU active site. The favorable enthalpy change could reflect the strong interaction between GSH and the active site, mainly hydrogen bonds as observed in the crystallographic structure (Figure 4-A). Similar observations have been found for other GSTs. The thiol from GSH is hydrogen bonded to S14, while it also has an interaction with K41. This binding mode is different to the structure of GSX-MiGSTU complex which does not show the hydrogen bond between S14 and the GSX sulfur atom. This explains the differences in ΔH values between GSH and GSX, because both present polar interactions through glutathione backbone [59–61].

The subtle conformational change that takes place upon GSH binding prepares the H-site for xenobiotic binding. Hydrophobic residues are exposed and these may account for the unfavorable entropy component. However, these conformational changes may be necessary for the formation of the H-site and tight binding of hydrophobic compounds. Conformational changes induced by substrate binding have been observed in several GST isoenzymes, like human GSTA1-1 and GSTP1-1 [62, 63] as well as maize GSTF1-1 [64] and sorghum GSTU4-4 [35]. However, this is the first structural study that reports a comparison between an apo and GSH-bound GST from plants.

The GST dimer has been described as the stacking of two symmetrical arginine residues in a lock and key hydrophobic interaction for Sigma, Mu, Tau and Pi-class GSTs [65]. An electrostatic interaction between D77 (helix 3) and R93 and R97 from the opposite monomer (helix 4), was found in Tau-class GST (Figure 2). The residue R93 at the apo structure has two alternate conformations, reflecting the mobility of the guanidinium group, and both conformations are equally accessible for favorable electrostatic contacts with the acidic group. Helix 4 has more hydrophobic residues that the rest of the helices contribute to the dimer interface. A94 has Van der Waal contacts with I70, and the latter contacts F98. A hydrophobic zipper is provided by W99 contact with F98 and C66. The interface area was very similar for the apo and GST-bound dimer (11,335 and 11,476 Å2), suggesting that substrate binding has no effect upon dimerization. In the MiGSTU-GSX structure, contact with S14 is lost, and the hexyl moiety contacts W108 and W169.

MiGSTU showed very high activity during the tests using the xenobiotic CDNB, the kinetic results are within the range reported for other plant GST values, having more affinity to GSH that CDNB, which it is to be expected since it is their natural substrate.

The information from the isothermal titration calorimetry indicates that each enzyme unit has two binding sites for GSH, i.e. consists of two monomers and in each of them, there is a GSH binding site. Thus, this information gives us evidence that the enzyme is dimeric, plus a different affinity for each monomer is presented in this system.

In this report, we present three crystal structures, one without ligand (apo), one with the cofactor GSH and one with the ternary complex analog GSX. The conformational change induced by GSH on the site G was not as severe and specific interactions occurred between S14 and the GSH thiol group. Interestingly, the unoccupied H-site found in the MIGSTU-GSH structure matches with the unfavorable entropic component found during GSH titration, that is compensated when GSX binds to G- and H-sites. These results encourage further structural and thermodynamic studies into the ligandin function of plant Tau GSTs.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Plant Tau-class of GST enzymes are less understood compared to their mammalian counterparts.

Enzymatic, thermodynamic and crystallographic studies of mango Tau GST are presented.

Binding of GSH is mediated by enthalpic effects and hydrogen bonds to the G-site

Alkylated GSH analogues like GSX is tightly bound by entropic compensation and hydrophobic interactions to the H-site

Overall the calorimetric and crystallographic data explain the conformational changes that led to an efficient enzyme that bind and process xenobiotics.

Acknowledgments

M. Islas-Osuna thanks Mexico’s National Research Council for Science and Technology for grant CONACYT CB-2012-178296. I. Valenzuela-Chavira thanks CONACYT for graduate studies scholarship. Dr. Lopez-Zavala thanks CONACYT for support by Fondo Consolidación Institucional (RET-I0007-2015-01/250973). A. Arvizu-Flores thanks grant INFR-2013-01-205617 from CONACYT to acquire the ITC equipment. R. Sotelo-Mundo thanks CONACYT for an equipment grant to acquire the X-ray diffractometer used in this work (INFR-2014-01-225455). We thank Dr. German Lukaszewicz (Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Argentina) for advice on phylogenetic sequence analysis. We thank the NSLS-SSRL user transition program supported jointly by the LSBR, NSLSII and SMB, SSRL under NIH-NIGMS grants P41GM111244 and P41GM103393, and DOE BER contracts DE-SC0012704. SSRL is operated under DOE BES contract DE-AC02-76SF00515.

Abbreviations

- MiGSTU

Mangifera indica glutathione-S-transferase Tau class

- GSH

glutathione

- GSX

S-hexyl glutathione

- CDNB

1-chloride-2,4-dinitrobencene

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions

IVC designed the research, conducted the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper; CACV designed the research, conducted the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper; AAAF designed the research, conducted the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper; HSP conducted the experiments and wrote the paper, analyzed the data; AALZ analyzed the data; KDGO designed the research and analyzed data; JHP analyzed the data and conducted experiments; ERP designed the research; VS conducted the experiments and analyzed the data; RRSM designed the research, conducted the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper; MAIO; designed the research and wrote the paper. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Armstrong RN. Structure, catalytic mechanism, and evolution of the glutathione transferases. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:2–18. doi: 10.1021/tx960072x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smart RC, Hodgson E. Molecular and Biochemical Toxicology. John Wiley & Sons Inc; Hoboken, N.J., USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chronopoulou E, Madesis P, Asimakopoulou B, Platis D, Tsaftaris A, Labrou NE. Catalytic and structural diversity of the fluazifop-inducible glutathione transferases from Phaseolus vulgaris. Planta. 2012;235:1253–1269. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1572-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conn S, Curtin C, Bézier A, Franco C, Zhang W. Purification, molecular cloning, and characterization of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) from pigmented Vitis vinifera L. cell suspension cultures as putative anthocyanin transport proteins. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2008;59:3621–3634. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon DP, Edwards R. Glutathione transferases. The Arabidopsis Book/American Society of Plant Biologists. 2010;8 doi: 10.1199/tab.0131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kampranis SC, Damianova R, Atallah M, Toby G, Kondi G, Tsichlis PN, Makris AM. A novel plant glutathione S-transferase/peroxidase suppresses Bax lethality in yeast. Science Signaling. 2000;275:29207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002359200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marrs KA. The functions and regulation of glutathione S-transferases in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 1996;47:127–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chelvanayagam G, Parker M, Board P. Fly fishing for GSTs: a unified nomenclature for mammalian and insect glutathione transferases. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2001;133:256–260. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ketterer B. A bird’s eye view of the glutathione transferase field. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2001;138:27. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(01)00277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon DP, Lapthorn A, Edwards R. Plant glutathione transferases. Genome Biol. 2002;3:3004.3001–3004.3010. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-3-reviews3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards R, Cole DJ. Glutathione Transferases in Wheat (“Triticum”) Species with Activity toward Fenoxaprop-Ethyl and Other Herbicides. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 1996;54:96–104. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan T, Yang ZL, Yang X, Liu YJ, Wang XR, Zeng QY. Extensive functional diversification of the Populus glutathione S-transferase supergene family. The Plant Cell Online. 2009;21:3749–3766. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheehan D, Meade G, Foley VM, Dowd CA. Structure, function and evolution of glutathione transferases: implications for classification of non-mammalian members of an ancient enzyme superfamily. Biochemical Journal. 2001;360:1. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3600001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohsenzadeh S, Esmaeili M, Moosavi F, Shahrtash M, Saffari B, Mohabatkar H. Plant glutathione S-transferase classification, structure and evolution. Afr J Biotech. 2011;10:8160–8165. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J, Xing XJ, Tian YS, Peng RH, Xue Y, Zhao W, Yao QH. Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants Expressing Tomato Glutathione S-Transferase Showed Enhanced Resistance to Salt and Drought Stress. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilce M, Parker MW. Structure and function of glutathione S-transferases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1994;1205:1. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)90086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cummins I, Dixon DP, Freitag-Pohl S, Skipsey M, Edwards R. Multiple roles for plant glutathione transferases in xenobiotic detoxification. Drug Metab Rev. 2011;43:266–280. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2011.552910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGonigle B, Keeler SJ, Lau SMC, Koeppe MK, O’Keefe DP. A genomics approach to the comprehensive analysis of the glutathione S-transferase gene family in soybean and maize. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:1105–1120. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.3.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang C, Spokoyny AM, Zou YK, Simon MD, Pentelute BL. Enzymatic “Click” Ligation: Selective Cysteine Modification in Polypeptides Enabled by Promiscuous Glutathione S-Transferase. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2013;52:14001–14005. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Axarli I, Muleta AW, Chronopoulou EG, Papageorgiou AC, Labrou NE. Directed evolution of glutathione transferases towards a selective glutathione-binding site and improved oxidative stability. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Habig WH, Pabst MJ, Jakoby WB. Glutathione S-transferases the first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:7130–7139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Contreras-Vergara CA, Valenzuela-Soto E, García-Orozco KD, Sotelo-Mundo RR, Yepiz-Plascencia G. A Mu-class glutathione S-transferase from gills of the marine shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei: Purification and characterization. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology. 2007;21:62–67. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Macromolecular Crystallography, Pt A. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thom R, Cummins I, Dixon DP, Edwards R, Cole DJ, Lapthorn AJ. Structure of a tau class glutathione S-transferase from wheat active in herbicide detoxification. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7008–7020. doi: 10.1021/bi015964x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNicholas S, Potterton E, Wilson K, Noble M. Presenting your structures: the CCP4mg molecular-graphics software. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography. 2011;67:386–394. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911007281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wallace AC, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. Ligplot - a Program to Generate Schematic Diagrams of Protein Ligand Interactions. Protein Engineering. 1995;8:127–134. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laskowski RA, Swindells MB. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:2778–2786. doi: 10.1021/ci200227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lo Piero AR, Mercurio V, Puglisi I, Petrone G. Different roles of functional residues in the hydrophobic binding site of two sweet orange tau glutathione S-transferases. FEBS J. 2010;277:255–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thom R, Cummins I, Dixon DP, Edwards R, Cole DJ, Lapthorn AJ. Structure of a tau class glutathione S-transferase from wheat active in herbicide detoxification. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7008–7020. doi: 10.1021/bi015964x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Axarli I, Dhavala P, Papageorgiou AC, Labrou NE. Crystallographic and Functional Characterization of the Fluorodifen-inducible Glutathione Transferase from Glycine max Reveals an Active Site Topography Suited for Diphenylether Herbicides and a Novel L-site. Journal of molecular biology. 2009;385:984–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Axarli I, Dhavala P, Papageorgiou AC, Labrou NE. Crystal structure of Glycine max glutathione transferase in complex with glutathione: investigation of the mechanism operating by the Tau class glutathione transferases. Biochem J. 2009;422:247–256. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeng QY, Wang XR. Catalytic properties of glutathione-binding residues in a tau class glutathione transferase (PtGSTU1) from Pinus tabulaeformis. Febs Lett. 2005;579:2657–2662. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dautt-Castro M, Ochoa-Leyva A, Contreras-Vergara CA, Pacheco-Sanchez MA, Casas-Flores S, Sanchez-Flores A, Kuhn DN, Islas-Osuna MA. Mango (Mangifera indica L.) cv. Kent fruit mesocarp de novo transcriptome assembly identifies gene families important for ripening. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:62. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edwards R, Dixon DP, Walbot V. Plant glutathione-S-transferases: enzymes with multiple functions in sickness and in health. Trends in Plant Science. 2000;5:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01601-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan C, Lam HM. A putative lambda class glutathione S-transferase enhances plant survival under salinity stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:570–579. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Labrou NE, Papageorgiou AC, Pavli O, Flemetakis E. Plant GSTome: structure and functional role in xenome network and plant stress response. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 32:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andujar-Sanchez M, Smith AW, Clemente-Jimenez JM, Rodriguez-Vico F, Las Heras-Vazquez FJ, Jara-Perez V, Camara-Artigas A. Crystallographic and thermodynamic analysis of the binding of S-octylglutathione to the Tyr 7 to Phe mutant of glutathione S-transferase from Schistosoma japonicum. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1174–1183. doi: 10.1021/bi0483110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quesada-Soriano I, Baron C, Garcia-Maroto F, Aguilera AM, Garcia-Fuentes L. Calorimetric studies of ligands binding to glutathione S-transferase from the malarial parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Biochemistry. 52:1980–1989. doi: 10.1021/bi400007g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Damm KL, Carlson HA. Gaussian-weighted RMSD superposition of proteins: a structural comparison for flexible proteins and predicted protein structures. Biophys J. 2006;90:4558–4573. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.066654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), 2015.10. Chemical Computing Group Inc; Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 2R7: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perbandt M, Burmeister C, Walter RD, Betzel C, Liebau E. Native and inhibited structure of a Mu class-related glutathione S-transferase from Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1336–1342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Atkinson HJ, Babbitt PC. Glutathione transferases are structural and functional outliers in the thioredoxin fold. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11108–11116. doi: 10.1021/bi901180v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagano N, Ota M, Nishikawa K. Strong hydrophobic nature of cysteine residues in proteins. Febs Lett. 1999;458:69–71. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skopelitou K, Muleta AW, Papageorgiou AC, Chronopoulou E, Labrou NE. Catalytic features and crystal structure of a tau class glutathione transferase from Glycine max specifically upregulated in response to soybean mosaic virus infections. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1854:166–177. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basantani M, Srivastava A. Plant gluthatione transferases - a decade falls short. Botany. 2007;85:443–456. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Edwards R, Dixon DP. Plant glutathione transferases. Methods Enzymol. 2005;401:169–186. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)01011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thom R, Dixon DP, Edwards R, Cole DJ, Lapthorn AJ. The structure of a zeta class glutathione-S-transferase from “Arabidopsis thaliana”: characterisation of a GST with novel active-site architecture and a putative role in tyrosine catabolism. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2001;308:949–962. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lan T, Yang ZL, Yang X, Liu YJ, Wang XR, Zeng QY. Extensive Functional Diversification of the Populus Glutathione S-Transferase Supergene Family. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3749–3766. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu YJ, Han XM, Ren LL, Yang HL, Zeng QY. Functional Divergence of the Glutathione S-Transferase Supergene Family in Physcomitrella patens Reveals Complex Patterns of Large Gene Family Evolution in Land Plants. Plant Physiol. 2013;161:773–786. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.205815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hayes JD, Flanagan JU, Jowsey IR. Glutathione transferases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:51–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gronwald JW, Plaisance KL. Isolation and characterization of glutathione S-transferase isozymes from sorghum. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:877–892. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.3.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kilili KG, Atanassova N, Vardanyan A, Clatot N, Al-Sabarna K, Kanellopoulos PN, Makris AM, Kampranis SC. Differential roles of Tau class glutathione S-transferases in oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24540–24551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309882200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hou L, Honaker MT, Shireman LM, Balogh LM, Roberts AG, Ng K-c, Nath A, Atkins WM. Functional promiscuity correlates with conformational heterogeneity in A-class glutathione S-transferases. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23264–23274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700868200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ortiz-Salmeron E, Yassin Z, Clemente-Jimenez MJ, Las Heras-Vazquez FJ, Rodriguez-Vico F, Baron C, Garcia-Fuentes L. Thermodynamic analysis of the binding of glutathione to glutathione S-transferase over a range of temperatures. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:4307–4314. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaplan W, Husler P, Klump H, Erhardt J, Sluis-Cremer N, Dirr H. Conformational stability of pGEX-expressed Schistosoma japonicum glutathione S-transferase: a detoxification enzyme and fusion-protein affinity tag. Protein Sci. 1997;6:399–406. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lim K, Ho JX, Keeling K, Gilliland GL, Ji X, Ruker F, Carter DC. Three-dimensional structure of Schistosoma japonicum glutathione S-transferase fused with a six-amino acid conserved neutralizing epitope of gp41 from HIV. Protein Sci. 1994;3:2233–2244. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hegazy UM, Mannervik B, Stenberg G. Functional role of the lock and key motif at the subunit interface of glutathione transferase P1-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9586–9596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sinning I, Kleywegt GJ, Cowan SW, Reinemer P, Dirr HW, Huber R, Gilliland GL, Armstrong RN, Ji XH, Board PG, Olin B, Mannervik B, Jones TA. Structure Determination and Refinement of Human-Alpha Class Glutathione Transferase-A1-1, and a Comparison with the Mu-Class and Pi-Class Enzymes. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1993;232:192–212. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prade L, Huber R, Bieseler B. Structures of herbicides in complex with their detoxifying enzyme glutathione S-transferase - explanations for the selectivity of the enzyme in plants. Struct Fold Des. 1998;6:1445–1452. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Prade L, Hof P, Bieseler B. Dimer interface of glutathione S-transferase from Arabidopsis thaliana: influence of the G-site architecture on the dimer interface and implications for classification. Biol Chem. 1997;378:317–320. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1997.378.3-4.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.