Abstract

Objective

To learn if a quality of care Medicaid child psychiatric consultation service implemented in three different steps was linked to changes in statewide child antipsychotic utilization.

Data Sources/Study Setting

Washington State child psychiatry consultation program primary data and Medicaid pharmacy division antipsychotic utilization secondary data from July 1, 2006, through December 31, 2013.

Study Design

Observational study in which consult program data were analyzed with a time series analysis of statewide antipsychotic utilization.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

All consultation program database information involving antipsychotics was compared to Medicaid pharmacy division database information involving antipsychotic utilization.

Principal Findings

Washington State's total child Medicaid antipsychotic utilization fell from 0.51 to 0.25 percent. The monthly prevalence of use fell by a mean of 0.022 per thousand per month following the initiation of elective consults (p = .004), by 0.065 following the initiation of age/dose triggered mandatory reviews (p < .001), then by another 0.022 following the initiation of two or more concurrent antipsychotic mandatory reviews (p = .001). High‐dose antipsychotic use fell by 57.8 percent in children 6‐ to 12‐year old and fell by 52.1 percent in teens.

Conclusions

Statewide antipsychotic prescribing for Medicaid clients fell significantly at different rates following each implementation step of a multilevel consultation and best‐practice education service.

Keywords: Antipsychotic agents, child and adolescent psychiatry, referral and consultation, Medicaid, outcome assessment (health care)

There has been a profound growth in antipsychotic prescriptions for children nationally over the past two decades (Alexander et al. 2011; Matone et al. 2012; Olfson et al. 2012; Penfold et al. 2013; Zito et al. 2013; Kreider et al. 2014). The most recently available reports indicate this rising trend of child antipsychotic use has been stabilizing, but not falling (Stein et al. 2014; Olfson, Druss, and Marcus 2015). Prevalence of child antipsychotic use have been far from uniform in different demographic groups, in that children with Medicaid coverage have been twice as likely to receive antipsychotics as those with private insurance, and those in foster care have even higher prescription prevalence (Zito et al. 2008; U.S. Government Accounting Office 2012; Burcu et al. 2014). In Washington State where this study occurs, the rate of increasing second‐generation antipsychotic use among Medicaid‐enrolled foster care children had been reported as the third highest nationally between 2002 and 2007 (Rubin et al. 2012). While there is evidence that antipsychotics yield benefits for several different pediatric indications beyond psychotic disorders, such as the irritability associated with autism, off‐label use exceeds use for approved indications (Matone et al. 2012; Zito et al. 2013). Antipsychotic medications can have serious side effects, such that for some conditions for which they are prescribed there is insufficient evidence available about their efficacy, tolerability, and safety (Correll and Carlson 2006; Correll et al. 2009; Andrade et al. 2011; Findling et al. 2011). A concern in the peer‐review literature has been adherence of prescribing clinicians for Medicaid‐insured children to follow guidelines for safe and quality prescribing of antipsychotics (Rettew et al. 2015).

Primary care providers prescribe the majority of all psychotropic medications to children in the United States, which for many children includes antipsychotics (Olfson et al. 2012; Achieving the promise 2013). In recognition of this new role of primary care practices, about half of U.S. states have implemented some form of pediatric psychiatry consultation to primary care programs (Klein and Hostetter 2014; National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs n.d.). Concerns about appropriateness of child psychotropic prescribing have led to a federal mandate that all states monitor psychotropic medication use for their children in foster care (Leslie et al. 2010; Child and Family Service Improvement and Innovation Act). Thirty‐one states have chosen to implement (mostly within the past 5 years) Medicaid prior authorization policies for pediatric use of atypical antipsychotic medications (Schmid, Burcu, and Zito 2015). Despite the intuitive care system value that both consultation to primary care and prescription oversight/second opinion review programs may offer, the data‐based impacts of these services for children have not been well studied.

In 2008, Washington State created an elective consult service intended to improve primary care access to high‐quality child and adolescent psychiatric expertise statewide (in what became known as the Partnership Access Line or “PAL”) (Thompson et al. 2009; Hilt et al. 2013). This service collaboration between Washington State Medicaid, University of Washington faculty psychiatrists, and Seattle Children's Hospital often directly addresses child antipsychotic use in primary care, even though addressing antipsychotic use was not this elective consult program's specific intent. Once established, the PAL elective consult service team was subsequently tasked with delivering mandatory medication second opinion reviews of antipsychotic prescriptions which fell outside of state‐set prescribing guidelines. This study analyzes the changes in state youth antipsychotic prescribing during implementation of these combined elective and mandatory medication review services.

Method

The Washington consult service intervention consists of subprograms implemented in three different steps: (1) elective consults for primary care, (2) mandatory medication reviews based on young age or high‐dose flags, and then (3) mandatory medication reviews for antipsychotic polypharmacy. Elective consult service work which included regional provider CME conferences began in January 2008, mandatory medication reviews regarding antipsychotics began in January 2009, and polypharmacy reviews began in July 2012. This analysis sets the total review period as from 1.5 years before clinical services started (July 1, 2006) to 1.5 years after the last of three steps in consult service implementation occurred (December 31, 2013). The consult team consisted of between two and eight child psychiatrists at any point in time who shared the role of delivering services. A more detailed description follows.

Elective Consults

All medical providers in the state were invited to access a child and adolescent psychiatrist by toll‐free phone number on weekdays 8 am to 5 pm to discuss any patient regardless of insurance type, with staffing arranged such that there would usually be immediate access to the psychiatrist. All child clinical information was obtained from community provider discussions with the consultant. The service also provides referral assistance, freely distributed practice guidelines, and free regional in‐person CME conferences on child mental health.

More detailed tele‐video or in‐person consults were provided for children with Medicaid insurance when requested by either the community provider or consultant. Consultants were expected to adhere to a best‐practice peer‐reviewed care guide (available at palforkids.org) on appropriate use of medications and nonpharmacologic interventions, with quarterly peer fidelity audits of the consultants’ work. For this analysis, elective consults were only coded as an antipsychotic consult if the patient was already prescribed an antipsychotic at first contact or if antipsychotic use was newly discussed during the consultation.

Mandatory Medication Reviews

Starting in January 2009, antipsychotic review triggers set by a state workgroup based on patient age and medication dose (available at http://www.hca.wa.gov/medicaid/billing/documents/memos/2009/09-04.pdf) were added to an existing ADHD medication review program (Prescription Drug Program [Link]). The state Medicaid division formed a workgroup of both mental health and primary care specialty leaders who reviewed published studies, practice parameters, prescribing guidelines, and local expert opinions, then developed the set of age and dose prescribing review flags that were subsequently approved for use by the state's Drug Utilization Review Board. In July 2012, an additional mandatory review trigger was added for the use of two or more concurrent antipsychotics for a period of more than 60 days.

The mandatory medication review process begins when the state pharmacy division flags prescriptions meeting review triggers at the point of sale, and contacts prescribers. Consultants are then asked to review state Medicaid division obtained records and to discuss the patient's care with the provider by phone. Consultants may discuss with prescribers alternative approaches to treatment, additional interventions to consider, and appropriate monitoring for adverse effects. Consultants then write out and share their recommendations, which the state pharmacy division references when making prescription approval decisions. For this analysis, mandatory medication review consults were coded as antipsychotic consults if an antipsychotic was included in the patient's regimen at time of contact with the medication review program.

Medication Utilization

The Washington Medicaid division provided for analysis monthly medication utilization and cost data from pharmacy claims for fee‐for‐service and managed‐care clients aged 0–18 years old from 2006 through 2013. As the same mandatory review system was utilized for both fee‐for‐service and managed‐care clients, to avoid any confusion regarding children moving between fee‐for‐service and managed‐care Medicaid plans over time, these two insurance groups were merged for this evaluation.

Monthly Time Series

We constructed a time series of numbers of children and adolescents filling at least one antipsychotic prescription in each month between July 1, 2006, and December 31, 2013. This time period included an 18‐month prepolicy period before the beginning of elective consultations regarding prescribing. Crude proportion of antipsychotic use was calculated on a monthly basis. The numerator included all individuals aged 0–18 years old who had at least one prescription for an antipsychotic during the month. The denominator included all individuals aged 0–18 years old who were enrolled in a Medicaid plan and eligible to receive services that month.

Time Series Analysis

We used segmented linear regression to test for changes in percent of antipsychotic users at the three policy implementation dates: elective consults, January 1, 2008; mandatory review based on age/dose, January 1, 2009; and mandatory review of ≥2 concurrent antipsychotics, July 1, 2012 (Wagner et al. 2002; Penfold and Zhang 2013). The analysis involved fitting a regression model with 93 observations (rate in each month). The ITS model included parameters for time, occurrence of the event (three policies above), time since the event, time squared, and any autoregressive parameters (to remove spurious inflation of significance). The specification of these models allowed the testing of immediate changes in the level of prescribing (i.e., shifts in the intercept associated with the event) and changes in the slope (i.e., inflection points captured by the time variables). We hypothesized that implementation of each phase of the program would be associated with downward inflections in the antipsychotic prescription fills over time (negative slope) but that sudden downward shifts in prescription fills would not occur. In other words, we expected the program to be associated with slowly decreasing percent of antipsychotic users rather than having a sudden, immediate impact.

Missing Data

There were 4 months of missing data spanning July 2008–October 2008. During this period, there was a change in the capture of prescriptions claims during a computer system upgrade that resulted in an apparent drop in antipsychotic utilization to nonsensical levels. We imputed the 4 months of missing antipsychotic prescription fills with the average monthly fills in the prior 12 months. This imputation strategy reduces the variance in the 2008 time period (which tends to overstate the statistical significance of any change in percent of antipsychotic users). An alternative strategy would be to censor those observations and fit the model with only observed data, but this strategy would have greatly overestimated the significance of a change in prescription fills because the fills in the latter months of 2008 were much lower. Thus, our choice of imputation tends to understate the magnitude and significance of predicated changes during the 2008 period.

Approval for this investigation was obtained from the Seattle Children's Hospital institutional review board.

Results

There were a total of 1,458 individual providers who received a direct patient consultation during the study period. Though provider specialty was not tracked with each contact, because there are only about 100 child psychiatrists in Washington State, the majority of consultations were with either pediatricians or family practitioners (Thomas and Holzer 2006). Antipsychotics were specifically discussed/reviewed with 611 of these providers via either an elective or mandatory consultation, 67 of whom (11 percent) received both an elective and mandatory consult during the study period. Additionally, 759 providers attended at one of the consult group's 31 general psychopharmacology education conferences, where appropriate antipsychotic use was discussed. Further description of the consultations is described below.

Elective Consults

There were 5,365 total elective consultations regarding 4,397 patients. Of these consults, 600 (11 percent of total elective consults) were about children already prescribed an antipsychotic prior to elective consultation, and in 408 (8 percent), the consultant and the primary provider discussed antipsychotic use for a child not already prescribed one. In sum, 1,008 (19 percent of total) elective consults were about patients already prescribed or being considered for prescription of an antipsychotic; these patients comprise the “elective consults” antipsychotic group in Table 1. Please see Table 1 regarding demographic information of the patients; race/ethnicity information was not collected. Table 2 provides details of elective consultations, including consultant recommendations.

Table 1.

Demographic Information of the Children Who Were the Subject of the Consults, No. (%)

| Elective Consults—Nonantipsychotic (n = 4,357) | Elective Consults—Antipsychotic (n = 1,008) | Medication Reviews—Nonantipsychotic (n = 1,865) | Medication Reviews—Antipsychotic (n = 870) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||

| 0–5 | 537 (12) | 92 (9) | 460 (25) | 125 (14) |

| 6–12 | 1,771 (41) | 470 (47) | 969 (52) | 411 (47) |

| 13–18 | 1,836 (42%) | 410 (41) | 433 (23) | 334 (38) |

| 19+ | 83 (2) | 28 (3) | 2 (<1) | 0 |

| Not recorded | 130 (3) | 8 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1,916 (44) | 280 (28) | 469 (25) | 250 (29) |

| Male | 2,305 (53) | 717 (71) | 1,365 (73) | 611 (70) |

| Unknown | 136 (3) | 11 (1) | 31 (2) | 9 (1) |

| Insurance type | ||||

| Medicaid | 2,225 (51) | 716 (71) | 1,865 (100) | 870 (100) |

| Private | 1,902 (44) | 273 (27) | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 163 (4) | 13 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| None | 67 (2) | 6 (<1) | 0 | 0 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of PAL Elective Consults and Mandatory Medication Review Consults Grouped by Whether Consult Involved an Antipsychotic

| No Antipsychotic in the Elective Consult | Antipsychotic in the Elective Consult | |

|---|---|---|

| Elective consult | ||

| Number of consultations | 4,357 | 1,008 |

| Number of unique primary care providers | 985 | 399 |

| Mean consult call duration, minutes | 13.5 | 16 |

| Patient taking an antipsychotic at time of consult | n/a | 600 (60%) |

| Consultant recommended an antipsychotic start or increase | n/a | 389 (39%) |

| Consultant recommended an antipsychotic stop or decrease | n/a | 161 (16%) |

| Consultant discussed antipsychotic use in general with providera | n/a | 270 (27%) |

| New psychosocial treatment (i.e., psychotherapy) recommended | 3,684 (85%) | 871 (86%) |

| No Antipsychotic in the Mandatory Medication Review | Antipsychotic in the Mandatory Medication Review | |

|---|---|---|

| Mandatory medication review | ||

| Number of consultations | 1,865 | 870 |

| Number of unique providers | 466 | 279 |

| Review trigger—age | 460 (25%) | 125 (14%) |

| Review trigger—dose | 354 (19%) | 438 (50%) |

| Review trigger—combination | 992 (53%) | 307 (35%) |

| Consultant recommended state approve the medication regimen | 1,352 (73%) | 583 (67%) |

| Consultant recommended a limited regimen approval during a planned treatment modificationb | 342 (18%) | 214 (25%) |

| Consultant recommended prescriber change the medication regimen before state approval | 171 (9%) | 73 (8%) |

For example, consultant may have noted that an antipsychotic could be reasonable to consider in the patient's care in the future, but only after other specific interventions were tried first.

For example, consultant may have approved two concurrent antipsychotics during a time‐limited cross‐taper.

Mandatory Medication Reviews

There were a total of 2,734 mandatory medication reviews, 870 (32 percent) of which directly addressed antipsychotic use. Of the children who were the subject of a mandatory antipsychotic medication review, 214 (25 percent) were receiving five or more psychotropic medications prior to the review. Please see Table 2 for details of the mandatory medication review consultations, including consultant recommendations.

State Medication‐Prescribing Trends

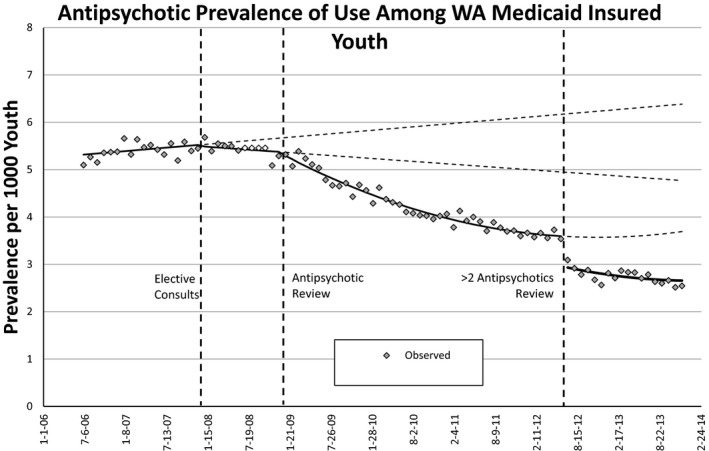

State prescribing trends show a decrease in total number of child antipsychotic users since program start, and a simultaneous increase in total number of Medicaid enrollees. In July 2006, there were 2,826 antipsychotic users among 554,461 Medicaid enrollees aged 0–18 years old (0.51 percent of enrollees were antipsychotic users). At our data endpoint in December 2013, despite Medicaid enrollee numbers growing by 186,855, the number of antipsychotic users had decreased by 940 (0.25 percent of enrollees were antipsychotic users)—a 49 percent decrease in enrollee antipsychotic users. Figure 1 shows the crude monthly prevalence of use of antipsychotics during the study period. Prior to 2008, prescription fills increased from approximately 5.1 to 5.6 per 1,000 enrollees. The introduction of elective consults in January 2008 was associated with a decreasing slope in the monthly prevalence of use of about 0.02 per thousand per month (p = .004). The monthly prevalence of use decreased from about 5.68 to 5.29 per thousand eligible enrollees during 2008. The introduction of mandatory second opinion was associated with a further decrease in antipsychotic utilization. Between January 2009 and June 2012, the prevalence of youth filling antipsychotic prescriptions decreased from 5.32 to 3.54 per 1,000 eligible enrollees. Both the time and time2 (slope) coefficients for this period were significant (see Table 3). Finally, the introduction of mandatory review of ≥2 concurrent antipsychotics was associated with an immediate drop in utilization from 3.54 to 2.81 per 1,000 eligible enrollees. There was a further slight decrease in antipsychotic prescription fills over the following months of about 0.02 per thousand per month (p = .001). The counterfactual trend is the rate that would have been observed given the trend prior to the consults. The observed prevalence of use was 2.5 per 1,000 at data end point, and a prevalence of 6.4 per 1,000 would have been expected given the preelective consult trend.

Figure 1.

Ratio of Atypical Antipsychotic Users/Child Medicaid Enrollees Decreased after Implementation of Each Review Phase

Table 3.

Changes in the Level and Slopea of the Antipsychotic (AP) Prescription Fills after Implementation of Each Review Phase (Autoregressive Parameters Assumed Given)

| Variable | DF | Estimate | Standard Error | t‐value | Approx, Pr > |t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1 | 5.304 | 0.043 | 124.13 | <.0001 |

| Elective consultation (level) | 1 | −0.023 | 0.066 | −0.35 | .726 |

| Trend after elective consultation (slope) | 1 | −0.022 | 0.007 | −2.97 | .004 |

| AP review (level) | 1 | −0.011 | 0.061 | −0.18 | .854 |

| Trend after AP review (slope) | 1 | −0.065 | 0.008 | −8.42 | <.0001 |

| Trend after AP review squared (slope) | 1 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 8.65 | <.0001 |

| ≥2 AP review (level) | 1 | −0.633 | 0.046 | −13.65 | <.0001 |

| Trend after ≥2 AP review (slope) | 1 | −0.022 | 0.006 | −3.46 | .001 |

| Secular trend overall (slope) | 1 | 0.012 | 0.004 | 3.33 | .001 |

“Level” changes indicate immediate downward shifts in the rate (intercept changes) and “slope” changes indicate increase or decrease in the trend.

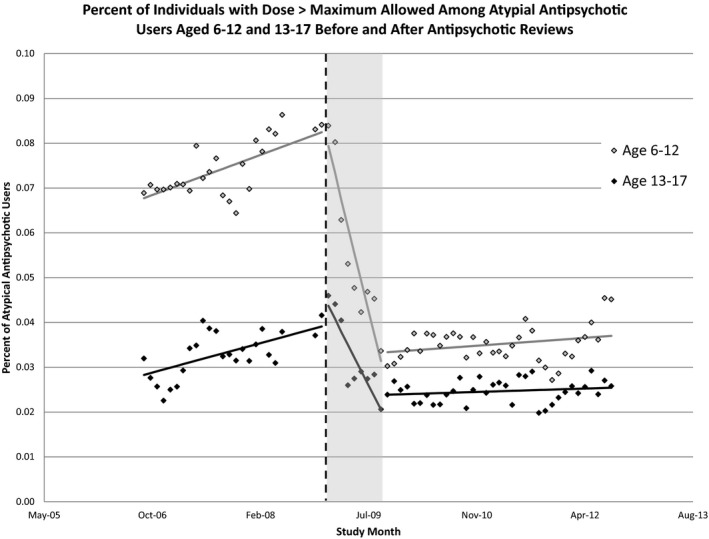

Figure 2 shows the change in the percentage of individuals prescribed antipsychotics at a dose greater than the state dose limits, stratified by children aged 6–12 years and adolescents aged 13–17 years. The review process was associated with a dramatic decrease in dose > maximum allowed limit in the next 8 months following implementation. The percentage of high‐dose use among children aged 6–12 years old using antipsychotics fell from 8.3 percent to about 3.5 percent between January and September of 2009 (a decrease of 57.8 percent). A smaller absolute change—no less dramatic—occurred among adolescents using antipsychotics with the percentage of dose > maximum dropping from 4.6 percent in January to about 2.2 percent by the fall of 2009 (a 52.1 percent decrease).

Figure 2.

- Note. *Shaded bar represents 9‐month period from start of reviews until change in use of antipsychotic at dose > maximum allowed stabilized.

Discussion

Within Washington State, the pediatric antipsychotic use prevalence among Medicaid‐covered children reversed its preexisting growth trend following initiation of these combined elective and mandatory consultation services. This is consistent with the direction of reported outcomes of one other state's antipsychotic prior authorization program during a similar time period; however, the degree of change in antipsychotic prescribing in Washington was more pronounced (Stein et al. 2014). The 49 percent reduction in the child Medicaid antipsychotic utilization prevalence seen in Washington State following implantation of these consultation programs represents a dramatic change in statewide treatment habits. Some subcategories of prescribing changed even more during this period, such as high‐dose antipsychotic use falling by 57.8 percent in children aged 6–12 years old.

Placing Washington's antipsychotic utilization into a national context, it has been reported that the percentage of youths around the country receiving antipsychotic drugs increased from 0.9 percent in 2003–2005 to 1.2 percent in 2010–2012 (Olfson, Druss, and Marcus 2015). Therefore, Washington Medicaid's specific percentage of youth using antipsychotics decreasing from 0.57 percent in 2008 to 0.25 percent in 2013 is quite a different tale than this national trend. Converting these percentages into absolute numbers, there were 940 fewer Medicaid covered children receiving antipsychotics at the evaluation period end when compared to the start. This reduction in the total number of users occurred although the total number of Medicaid covered children in Washington increased by 34 percent during the study period, which would have been predicted to otherwise increase the total number of antipsychotic utilizers. The notable decrease in antipsychotic utilizers during the study period raises the question of what impact elective consults and mandatory medication reviews had on this change to prescribing in the State.

There were a combined 234 occasions when a program consultant made a recommendation to stop or decrease a child's antipsychotic in the course of either a mandatory review or elective consultation. Therefore, the time series link between consult services and reduced overall prescribing cannot be simply due to these 234 individual children having their treatment plans altered per the consultant's advice. There are two other main consult/review service influences that we consider pertinent here.

The first of these influences is the impact of enhanced education and training. Consultant‐to‐provider interactions create dialog about best practices with young people, and they facilitate prescriber behavior change in a way that is difficult to numerically quantify. Consultant recommended treatment principles in consultations and provider education courses were consistent with national guidelines, which include cautions about prescribing antipsychotics to children and using alternative treatments when clinically more appropriate (Findling et al. 2011). The impact of even a single consultation becomes magnified when a provider applies any enhanced knowledge to the care of all their patients, not just those about whom they have specifically consulted.

A second influence pertains to mandatory medication reviews in which an aspect of the intervention is the hassle factor deterrent, sometimes referred to as the Hawthorne effect. Providers may simply have learned the criteria for mandatory review and adjusted their prescribing accordingly to avoid reviews (Thompson et al. 2009). Of the program interventions, greater impact to prescribing occurred following the mandatory review interventions than the elective intervention. The steep decrease in antipsychotic prescribing that occurred following implementation of reviews for concurrent use of two or more antipsychotics may be due to providers stopping antipsychotics that were no longer clearly needed in patients’ regimens to avoid review. This would create a quality of care concern if some children who needed these medications failed to receive them. However, because the guidelines for antipsychotic medication access without a review were quite generous and because a recommendation for approval was the most common outcome of mandatory medication review consultations (only 8 percent of recommendations were to deny authorization outright), there is little ongoing concern about adverse secondary consequences from mandatory reviews.

Community provider feedback was systematically collected about these consultation programs, but feedback survey response rates were low enough to not necessarily represent the views of all providers. As would be expected, completed provider feedback was more positive for elective consults than for mandatory reviews, but overall even mandatory reviews were reasonably well received for something providers by definition did not ask to receive. Feedback surveys were completed after just 299 (11 percent) of the mandatory reviews, so there was likely a bias in motivation among survey completers. In mandatory review feedback, 93 percent of respondents indicated that medication review scheduling was timely and convenient. The statement “This review process was useful” averaged 4.71 on a 0–7 Likert scale (7 = strongly agree) and “The consultant offered appropriate and helpful treatment suggestions for my patient” averaged 6.01 on the same scale. Elective consultation provider feedback is more positive as previously reported (Hilt et al. 2013). Since that prior report, an additional 621 feedback surveys were completed about elective consultations, with a 31 percent response rate. For elective consultations on a 5‐point Likert scale (5 = strongly agree), “My patient's care plan improved because of working with the PAL team” averaged a score of 4.75 and “I have increased my skills in managing the mental health care of my patients because of working with the PAL team” averaged a score of 4.71.

Limitations of this evaluation include absence of a state‐matched control which affects assumptions about cause and effect in a system as complicated as medication prescribing to children across a whole state. While the time series analysis strongly suggests a cause and effect linkage, we need to consider other factors such as whether the composition of children with Medicaid insurance changed during the study. Washington's child Medicaid enrollment criteria did not change during the evaluation period, but the state population increased by 8 percent (census.gov) and during an economic recession the number of Medicaid enrollees increased by 28 percent. We cannot rule out that some of these newer enrollees going on to Medicaid were clinically less likely to need antipsychotic treatment than those at study start, which could negatively influence prescribing prevalence. While the absence of a control group was a limitation, as the absolute number of Medicaid children using an antipsychotic fell by more than 900 clients, this suggests results were not simply an artifact.

Another possible factor in the decline in the prevalence of antipsychotic prescribing could be increased community concern about pediatric antipsychotic use unrelated to implementing these services. We cannot rule out that some of the decrease in antipsychotic prescribing might be due to secular changes in prescribing at the national level. However, data reported elsewhere indicate that antipsychotic prescribing continued to increase during the time period or at best slowed (Mojtabai and Olfson 2010; Olfson et al. 2012; Merikangas et al. 2013; Penfold et al. 2013; Olfson, Druss, and Marcus 2015). As national trends do not show a similar decline in prescribing, a local influence logically may be what affected prescribing in Washington State. Specific and logical changes to antipsychotic prescribing directly follow the program interventions supporting the cause and effect linkage (e.g., a decline in high‐dose prescribing follows initiation of high‐dose reviews, but not multiple antipsychotic reviews, which instead impact the number of antipsychotics prescribed).

Another limitation to the study is lack of clinical outcome information for the children who experienced medication changes as a result of the program. The potential for unintended consequences (undesirable medication substitution, residential placements, emergency room visits) of the prior authorization program does exist and could not be accounted for in this study design, which is a limitation to the presented analysis.

In sum, antipsychotic use of children with Medicaid insurance in Washington State decreased significantly following implementation of consultation services, with introduction of each element of the program linking to significant impacts. Prescription fills for using more than one concurrent antipsychotic and for using antipsychotics at very high dosages declined by roughly one half. These changes involved the care of more children than just those who were the subject of a consult. Other states and care systems may want to consider the Washington State experience when designing or seeking to understand the impact of programs to target care access and quality and shape prescribing practices.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: No financial or material support was received for this project. The clinical program is funded by the Washington State Health Care Authority. As the request here is for disclosures regarding support for the project, the above may be sufficient. In case other individual disclosures would be helpful to the editors, we include the following for inclusion at the editor's discretion: Dr. Hilt has received research funding from CMS, HRSA, NIMH, and a royalty from American Psychiatric Association Publishing. Dr. Penfold declares receiving research funding from Bristol‐Meyers Squibb, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, and Otsuka America Pharmaceutical.

The authors thank Jeff Thompson, M.D., former Chief Medical Officer, Washington State Medicaid, and Christopher Varley, M.D., University of Washington. Thank you to Dr. Thompson for helping the state establish this consultation service and to Dr. Varley for helping to establish the initial medication review guidelines.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

References

- “Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America.” 2013. President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health; Published July [accessed on December 16, 2015]. Available at http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/mentalhealthcommission/reports/FinalReport/downloads/downloads.html [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, G. C. , Gallagher S. A., Mascola A., Moloney R. M., and Stafford R. S.. 2011. “Increasing Off‐Label Use of Antipsychotic Medications in the United States, 1995‐2008.” Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 20: 177–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, S. E. , Lo J. C., Roblin D., and Fouayzi H.. 2011. “Antipsychotic Medication Use among Children and Risk of Diabetes Mellitus.” Pediatrics 128 (6): 1135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burcu, M. , Zito J. M., Ibe A., and Safer D.. 2014. “Atypical Antipsychotic Use Among Medicaid‐Insured Children and Adolescents: Duration, Safety, and Monitoring Implications.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 24 (3): 112–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child and Family Service Improvement and Innovation Act . 2011. (P.L. 112‐34). [accessed on May 7, 2015]. Available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-112publ34/content-detail.html

- Correll, C. U. , and Carlson H. E.. 2006. “Endocrine and Metabolic Adverse Effects of Psychotropic Medications in Children and Adolescents.” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 45 (7): 771–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll, C. U. , Manu P., Olshanskiy V., Napolitano B., Kane J. M., and Malhotra A. K.. 2009. “Cardiometabolic Risk of Second‐Generation Antipsychotic Medications during First‐Time Use in Children and Adolescents.” Journal of the American Medical Association 302 (21): 1765–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling, R. L. , Drury S. S., Jensen P. S., Rapoport J., and the AACAP Committee on Quality Issues . 2011. “Practice Parameter for the Use of Atypical Antipsychotic Medications in Children and Adolescents [accessed June 30, 2016]. Available at https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/practice_parameters/Atypical_Antipsychotic_Medications_Web.pdf

- Hilt, R. J. , Romaire M. A., McDonell M. G., Sears J. M., Krupski A., Thompson J. N., Myers J., and Trupin E. W.. 2013. “The Partnership Access Line: Evaluating a Child Psychiatry Consult Program in Washington State.” Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics 167 (2): 162–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, S. , and Hostetter M.. 2014. “In Focus: Integrating Behavioral Health and Primary Care.” The Commonwealth Fund August/September [accessed on December 16, 2015]. Available at http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletters/quality-matters/2014/August-September/in-focus [Google Scholar]

- Kreider, A. R. , Matone M., Bellonci C., dosReis S., Feudtner C., Huang Y. S., Localio R., and Rubin D. M.. 2014. “Growth in the Concurrent Use of Antipsychotics with Other Psychotropic Medications in Medicaid‐Enrolled Children.” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 53 (9): 960–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, L. K. , Mackie T., Dawson E. H., Bellonci C., Schoonover D. R., M Rodday A., Hayek M., and Hyde J.. 2010. “Multi‐State Study on Psychotropic Medication Oversight in Foster Care.” Study Report Tufts Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Published September [accessed on July 15, 2014]. Available at http://www.tuftsctsi.org/~/media/Files/CTSI/Library%20Files/Psychotropic%20Medications%20Study%20Report.ashx

- Matone, M. , Localio R., Huang Y. S., dosReis S., Feudtner C., and Rubin D.. 2012. “The Relationship between Mental Health Diagnosis and Treatment with Second‐Generation Antipsychotics over Time: A National Study of U.S. Medicaid‐Enrolled Children.” Health Services Research 47: 1836–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas, K. R. , He J. P., Rapoport J., Vitiello B., and Olfson M.. 2013. “Medication Use in US Youth with Mental Disorders.” Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics 167 (2): 141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai, R. , and Olfson M.. 2010. “National Trends in Psychotropic Medication Polypharmacy in Office‐Based Psychiatry.” Archives of General Psychiatry 67 (1): 26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs (n.d.). “Existing Programs” [accessed on December 16, 2015]. Available at http://www.nncpap.org/existing-programs.html

- Olfson, M. , Druss B. G., and Marcus S. C.. 2015. “Trends in Mental Health Care among Children and Adolescents.” New England Journal of Medicine 372: 2029–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson, M. , Blanco C., Liu S., Wang S., and Correll C.. 2012. “National Trends in the Office‐Based Treatment of Children, Adolescents, and Adults with Antipsychotics.” Archives of General Psychiatry 69 (12): 1247–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfold, R. B. , and Zhang F.. 2013. “Use of Interrupted Time Series Analysis in Evaluating Health Care Quality Improvements.” Academic Pediatrics 13 (6 Suppl): S38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfold, R. B. , Stewart C., Hunkeler E. M., Madden J. M., Cummings J. R., Owen‐Smith A. A., Rossom R. C., Lu C. Y., Lynch F. L., Waitzfelder B. E., Coleman K. J., Ahmedani B. K., Beck A. L., Zeber J. E., and Simon G. E.. 2013. “Use of Antipsychotic Medications in Pediatric Populations: What Do the Data Say?” Current Psychiatry Reports 15 (426): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescription Drug Program : additions to the list of limitations on certain drugs and changes to the Washington PDL and expedited authorization list. Olympia, WA: Department of Social and Health Services Health and Recovery Services Administration (Memo 09‐04). Issued: January 29, 2009. Available by request from http://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/prescription-drug-program/meetings-and-materials

- Rettew, D. C. , Greenblatt J., Kamon J., Neal D., Harder V., Wasserman R., Berry P., MacLean C. D., Hogue N., and McMains W.. 2015. “Antipsychotic Medication Prescribing in Children Enrolled in Medicaid.” Pediatrics 135 (4): 658–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D. , Matone M., Huang Y., dos Reis S., Feudtner C., and Lacalio R.. 2012. “Interstate Variation in Trends of Psychotropic Medication Use among Medicaid‐Enrolled Children in Foster Care.” Child Youth Services Review 34 (8): 1492–9. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, I. , Burcu M., and Zito J. M.. 2015. “Medicaid Prior Authorization Policies for Pediatric Use of Antipsychotic Medications.” Journal of the American Medical Association 313 (9): 966–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, B. D. , Leckman‐Westin E., Okeke E., Scharf D., Sorbero M., Chen Q., Chor K. H., Finnerty M., and Wisdom J. P.. 2014. “The Effects of Prior Authorization Policies on Medicaid‐Enrolled Children's Use of Antipsychotic Medications: Evidence from Two Mid‐Atlantic States.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 24 (7): 374–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C. R. , and Holzer C. E. 3rd. 2006. “The Continuing Shortage of Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists.” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 45 (9): 1023–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. , Varley C., McClellan J., Hilt R., Lee T., Kwan A. C., Lee T., and Trupin E.. 2009. “Second Opinions Improve ADHD Prescribing in a Medicaid‐Insured Community Population.” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 48 (7): 740–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Government Accounting Office . 2012. “Children's Mental Health, Concerns Remain about Appropriate Services for Children in Medicaid and Foster Care.” GAO Publications 13 (15) [accessed on December 16, 2015]. Available at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-15 [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, A. K. , Soumerai S. B., Zhang F., and Ross‐Degnan D.. 2002. “Segmented Regression Analysis of Interrupted Time Series Studies in Medication Use Research.” Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 27 (4): 299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zito, J. M. , Safer D. J., Sai D., Gardner J. F., Thomas D., Coombes P., Dubowski M., and Mendez‐Lewis M.. 2008. “Psychotropic Medication Patterns among Youth in Foster Care.” Pediatrics 121: e157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zito, J. M. , Burcu M., Ibe A., Safe D., and Mager L.. 2013. “Antipsychotic Use by Medicaid‐Insured Youths: Impact of Eligibility and Psychiatric Diagnosis across a Decade.” Psychiatric Services 64 (3): 223–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.