Abstract

Immune evasion and deregulation of energy metabolism play a pivotal role in cancer progression. Besides the coincidence in their historical documentation and concurrent recognition as hallmarks of cancer, both immune evasion and metabolic deregulation may be functionally linked as well. For example, the metabolic phenotype, particularly tumor glycolysis (aerobic glycolysis), impacts the tumor microenvironment (TME), which in turn acts as a major barrier for successful targeting of cancer by antitumor immune cells and other therapeutics. Similarly, in the light of recent research, it has been known that some of the immune sensitive antigens that are downregulated in cancer may also be restored or induced by cellular/metabolic stress. For instance, cancer cells downregulate the cell surface ligands such as MHC class I chain-related (MIC) protein-(A/B) that are normally upregulated in disease/pathological conditions. Noteworthy, the MHC class I chain-related protein A and B (MIC-A/B) are recognized by natural killer (NK) cells for immune elimination. Interestingly, MIC-A/B is stress inducible as demonstrated by oxidative stress and other cellular-stress factors. Consequently, stimulation of metabolic stress has also been shown to sensitize cancer cells to NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Taken together, data from recent reports imply that dysregulation of tumor glycolysis could facilitate induction of immune sensitive surface ligands leading to increased efficacy of antitumor immunotherapeutics. Nonetheless, dysregulated tumor glycolysis may also impact the TME and alter it from acidic, low pH into a therapeutically desirable TME that can enhance the effective infiltration of antitumor immune cells. In this mini-review, targeting tumor glycolysis has been discussed to evaluate its potential implications to enhance and/or facilitate anticancer immunity.

Keywords: cancer metabolism, tumor glycolysis, immunotherapy, tumor microenvironment

Introduction

Among different cancer treatment modalities immunotherapy enjoys the advantage of antigen-dependent specific targeting of cancer cells. Although the therapeutic potential of host immune system in affecting cancer progression has long been known (1), only in the recent decades research on the development of effective immunotherapy has gained momentum. Approval of immunotherapeutics by the Food and Drug Administration (USA) further signified immunotherapy as one of the potent and viable approaches for cancer treatment (2). During the recent expansion of the list of hallmarks of cancer, Hanahan and Weinberg (3) included “immune-evasion” and the “deregulation of energy metabolism” (i.e., metabolic reprogramming also referred as “altered energy metabolism”) as additional molecular signatures of cancer. Both the “deregulated energy metabolism” and the immune evasion occupy similar chronological history in terms of their initial documentation (more than several decades ago) (4, 5), followed by decades of paucity and the recent recognition as cancer hallmarks (3). Emerging reports suggest that besides the historical coincidence, these two phenotypes may be functionally linked as well (6). This mini-review aims at understanding the role of tumor glycolysis in the context of immune evasion and to discuss potential immunotherapeutic implications of taming tumor glycolysis.

Cancer Immune Evasion

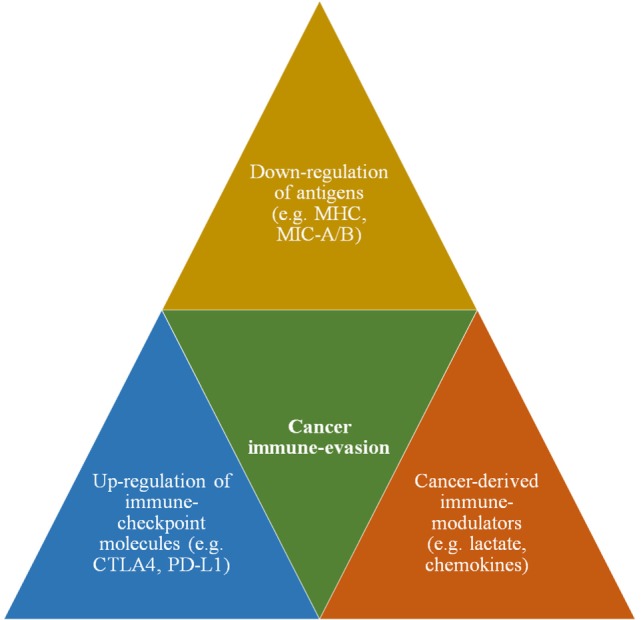

Cancer cell’s propensity to escape immune surveillance is known as cancer immune evasion (3). Substantial body of evidence unequivocally demonstrate that cancer cells employ several lines of biochemical and functional alterations to evade immune detection (7). Such immune-evasive mechanisms include cancer-derived immune modulators, upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules, and downregulation of tumor-specific antigens (Figure 1). Cancer-associated immune modulation is achieved via certain secretory products that include but are not limited to (i) cytokines (e.g., interleukins), (ii) chemokines (e.g., SDF-1) that promote the activation of tumor-associated macrophages, and (iii) establishment of an acidic tumor microenvironment (TME) that renders majority of antitumor immune cells less efficient or non-functional (8). Next, immune checkpoint ligands prevent or suppress the antitumor activity of immune cells by inhibitory interaction with corresponding receptors on immune cells. For example, the expression of CD80 ligand on cancer cell enables it to inhibit the immune reaction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) by binding with the specific receptor CTLA4. Similarly, the programmed death-ligand (PD-L 1,2) interferes with the antitumor function of CTLs by binding with PD-1 receptor. Finally, the downregulation of cancer-specific antigens such as major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules has been implicated as one of the prominent mechanisms to escape immune detection by T lymphocytes. Recent data indicate such downregulation also includes the antigens specific for natural killer (NK) cells. Experimental evidences on the ligands, MHC class I chain-related protein A or B (MIC-A/B) demonstrates that cancer cells downregulate these NKG2D ligands to prevent immune recognition by corresponding receptors on NK cells (9). Thus, antigens or ligands specific for T cells as well as NK cells are downregulated as parts of immune-escape mechanisms.

Figure 1.

A schematic showing major immune-evasive mechanisms that enable cancer cells to escape immune surveillance and antitumor immunity.

Among the innate (e.g., NK cells) and adaptive immune systems (e.g., T-cells), the latter has been under extensive preclinical and clinical investigation. Therefore, significant progress has been made in understanding the mechanistic details of T-cell-mediated antitumor immunity, leading to the development of potential therapies by harnessing T-cell’s ability to target cancer (10). For instance, the development of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against specific cancer antigens or tumor antigens has been very effective in specific targeting to enhance T-cell-mediated immunotherapy (11). However, such mAbs were frequently challenged with undesirable effects like the immunogenicity in patients and reduced efficiency in the recruitment of effectors cells (12). Hence, additional approaches were undertaken to overcome at least some of the impediments faced by such mAbs. Consequently, humanized chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells were developed which markedly reduced the undesirable immune reactions. However, the clinical outcomes were still less successful necessitating further research (12). Nevertheless, T-cell-dependent or -related potential therapeutics are advancing at an exponential rate toward the development of a viable strategy to achieve successful cancer treatment. Meanwhile, studies on the innate immune system such as NK cells have also been progressing remarkably to exploit potential opportunities for cancer therapy (13–15). Especially the adoptive cells transfer therapy has shown promising results and encouragement. Yet, irrespective of the type of immune therapeutics, the clinical benefits of immunotherapy have been realized primarily in hematological cancers (16, 17) and less efficient against solid malignancies.

Tumor Glycolysis

Several elegant reviews have discussed the biology and significance of tumor glycolysis (18, 19). Hence, considering the focus of this review, the tumor glycolysis will be discussed in the context of its role and relevance in immune evasion and immunotherapy, respectively. Clinical diagnosis of cancer using positron emission tomography relies on the accelerated rate of glucose metabolism, one of the metabolic signatures of cancer cells (20). This increased glucose utilization is accomplished by a metabolic switch to glycolysis, i.e., the process of conversion of glucose into pyruvate followed by lactate production in the absence of oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos). The pioneering work of the German scientist, Warburg (5, 21) documented for the first time that cancer cells exhibit glycolysis even in the presence of oxygen, hence popularly known as “aerobic glycolysis” or “Warburg effect.” Aerobic glycolysis or the tumor glycolysis produces fewer energy molecules (e.g., ATP) compared to the mitochondrial, OxPhos. Several elegant reviews (18, 22) have provided insights on the biological effects and advantages of such a “metabolic switch.” In fact, the metabolic switch or the “altered energy metabolism” is so frequent and common in majority, if not, all types of cancers, it has been included as one of the hallmarks of cancer (3). In this context, it is noteworthy that recent research demonstrates that aggressive phenotype of cancer is also associated with increased OxPhos, which relies on mitochondrial respiration (23, 24). However, considering the aim of this mini-review and the space limitation, the discussion on tumor metabolism will be limited to tumor glycolysis.

Clinically, tumor glycolysis has been found to be associated with some of the therapeutic challenges that impede successful cancer treatment. For example, tumor glycolysis has been implicated in therapeutic resistance (25) in chemotherapy (26), radiation therapy (27), etc. In this context, the TME has been implicated as one of the major barriers for successful targeting of cancer (28, 29). The composition of TME is primarily influenced by secretory/excretory products of cancer cells in addition to the tumor-associated fibroblasts. Lactate produced by glucose metabolism, particularly the glycolysis, is secreted/exported and remains in the TME. Hence, tumor glycolysis is one of the chief metabolic principles that orchestrate the constituents of TME. The extracellular accumulation of lactate contributes to the chemical gradient and pH of the TME (30). Experimental evidences demonstrate that the low pH or the acidity of TME either impedes the penetrability of therapeutics or renders them inactive and non-functional (30). Accordingly, effective elimination of cancer necessitates the integration of a strategy to overcome the TME barrier.

Tumor glycolysis contributes to the acidic microenvironment through the release of lactate and other low-pH ions into the extracellular milieu that in turn prevents or quenches the infiltration or efficacy of therapeutics. Thus, it is evident that tumor glycolysis invariably facilitates a protective barrier and maintains the efficient management cellular bioenergetics and redox balance in cancer. Thus, disruption of tumor glycolysis is imperative to destabilize cancer cells’ redox balance rendering them susceptible to therapeutic intervention. One of the well-investigated targets for the inhibition of tumor glycolysis is the enzyme, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), the enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate into lactate (31). Besides the inhibition of LDH, tumor glycolysis may also be disrupted by targeting any intermediate steps of glucose metabolism. For instance, inhibition of the enzyme hexokinase (32) or any other enzymes (33, 34) that catalyze subsequent reactions of glucose metabolism has been known to promote anticancer effects. Noteworthy, there is a distinctive advantage in targeting glycolytic steps preceding the step of lactate production. In other words, deregulation of tumor glycolysis by targeting glycolytic enzymes other than LDH may have additional desirable outcome. This is primarily due to the characteristic, “feed-back” inhibitory mechanism of glucose metabolism. Precisely, the accumulation metabolites of intermediate steps of glycolysis due to the inhibition of a particular enzyme eventually blocks or alleviates the rate of glucose catabolism in a negative feedback fashion. Thus, disruption of tumor glycolysis plausibly reduces the rate of glucose oxidation and utilization. Consequently, the energy demands of cancer cells will necessitate the utilization of alternative energy producing pathways, which is plausible due to the metabolic plasticity of cancer cells. One of the alternative pathways frequently witnessed in cancer cells to meet their energy demand is the glutamine metabolism, which relies on mitochondrial respiration. Thus, dysregulation of tumor glycolysis will necessitate cancer cells to depend on mitochondrial metabolism rendering them susceptible to any anti-mitochondrial approach using mitotropic agents (35, 36). Moreover, such unidirectional metabolic switch to mitochondrial metabolism also blocks the capacity of cancer cells to reprogram to glycolysis as the glucose consumption remains impaired due to the inhibition of glycolysis.

Dysregulation of Tumor Glycolysis and Immunosensitivity

As discussed above, in the absence of OxPhos, lactate is the metabolic end product of tumor glycolysis. The lactate thus produced is then exported to the external milieu via specific transporters called monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs). Lactate is a major source of the H+ ions that contributes to the acidification of TME, although other sources of H+ ions are prevalent (37). Disruption or dysregulation of glycolysis by the inhibition of LDH has been shown to rewire the metabolism toward mitochondrial-dependent OxPhos (38). Though such a metabolic plasticity allows cancer cells to survive, the intrinsic characteristics of OxPhos have been known as undesirable for the perpetuation of tumor growth. One of the metabolic outcomes of OxPhos is the generation of free radicals collectively known as reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS is required for the stabilization of one of the critical factors, the hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1 (39). Conversely, excessive accumulation of ROS is deleterious to subcellular structures and organelles (40). In fact, some of antineoplastic alkylating agents exert anticancer effects by the induction of ROS to cytotoxic levels (41). Next, as chronic accumulation of ROS is deleterious to subcellular organelles/membrane structures, it necessitates their neutralization or quenching by antioxidants (e.g., glutathione). In cancer cells, the level of antioxidants has been mitigated as the metabolic phenotype is primarily utilized for the synthesis of macromolecules that are critical for proliferation and growth. Noteworthy, antioxidants have also been implicated as potential anticancer agents as they eliminate ROS, which is required for the stabilization of HIF-1 (42). Thus, the maintenance of a redox balance with minimal ROS production to sustain HIF-1 regulation and downregulation of antioxidants is one of the critical requirements of cancer cells. Accordingly, the metabolic switch to glycolysis has been ascribed as one of the adaptive mechanisms to reduce the level of ROS generated via OxPhos (36).

Next, in solid tumors, the presence of TME has been recognized as one of the major barriers that hinders successful tumor elimination by antitumor immune cells. TME is a complex medium, which influences and gets influenced by, the metabolic phenotype of cancer (43). The biochemical composition and the pH of the TME are primarily governed by the secretory/excretory products of cancer cells as well as the adjacent stromal cells or cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs). Emerging data indicate that CAFs play a pivotal role in the maintenance of tumor growth (44). CAFs have been known to utilize one of the metabolic products of cancer, the lactic acid or lactate. Removal of lactate by CAFs regulates/reduces chronic extracellular acidification. In addition, the utilization of lactate by CAFs via mitochondrial OxPhos to meet their energy demands reduces their demand for glucose, leading to increased glucose availability for cancer cells. Thus, CAFs indirectly facilitate glucose availability to fuel tumor metabolism. If tumor glycolysis is disrupted and lactate production is alleviated, the CAFs will rely on glucose metabolism leading to a competition with cancer cells for glucose uptake. Thus, disruption of tumor glycolysis will necessitate cancer cells to utilize mitochondrial-dependent OxPhos to meet their energy requirements. This in turn would deregulate the redox balance due to overly production of ROS. In addition, such an increase in intracellular ROS level along with a competition by CAFs for glucose consumption likely to enforce a metabolic pressure. Thus, dysregulation of tumor glycolysis could render cancer cells metabolically weak and sensitive to therapeutic interference.

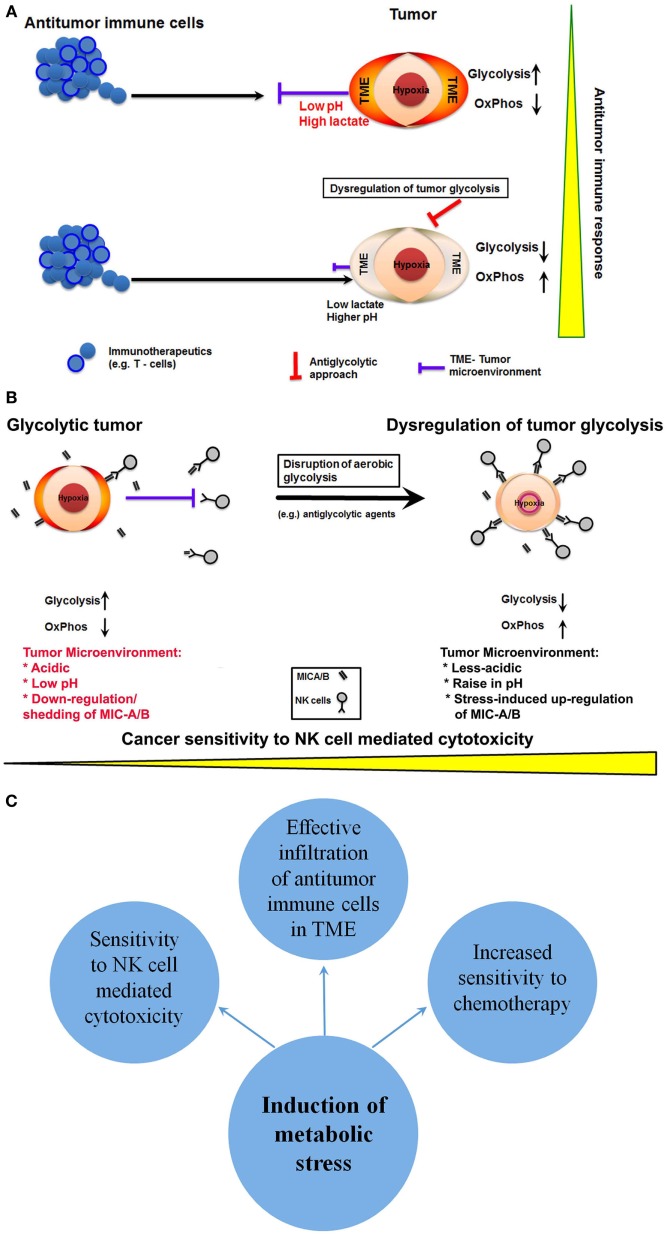

From the immunotherapy perspective, the abrogation or reduction of lactate production that in turn reduces the acidification of TME is a desirable consequence for effective infiltration of therapeutics including immune cells. Noteworthy, low pH and increased acidification of TME are principal reasons for the lack of efficacy or loss of function of several therapeutics including chemotherapeutics and immunotherapeutics (45). Comprehensibly, reduced acidification would facilitate enhanced penetrability of antitumor immune cells such as T-cells or NK cells or novel therapeutics like CAR-T cells (Figure 2A). In fact, sporadic reports have indicated that disruption of tumor glycolysis to limit the accumulation of lactate in TME could promote antitumor immune response (6, 46). Thus, dysregulation of glycolysis in cancer cells could facilitate effective targeting of cancer by antitumor immune cells.

Figure 2.

Potential anticancer immunotherapeutic opportunities of dysregulation of tumor glycolysis. (A) A schematic showing that dysregulation of tumor glycolysis alters tumor microenvironment that in turn could facilitate effective infiltration of antitumor immune cells. (B) Diagrammatic representation of dysregulation of tumor glycolysis to upregulate the stress-inducible surface ligands for further sensitization to natural killer (NK) cell-mediated cytotoxicity. (C) A schematic showing potential outcomes of induction of metabolic stress by dysregulation of tumor glycolysis.

Next, the NK cells represent the first line of defense, and preclinical reports indicate that NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity affects cancer cells (13, 47). However, recognition of cancer cells by NK cells depends upon two critical factors; (a) the recognition of specific antigens known as NK group 2D ligands (NKG2DLs) on the cancer cell and (b) the infiltration through TME. As discussed above, the latter may be overcome by dysregulation of tumor glycolysis, which will alter the acidic TME into less-acidic medium enabling effective infiltration of NK cells. However, the NK cell recognition of cancer by specific NKG2D ligands such as ULBP, MIC-A/B relies on their level of expression on target cells. Paradoxically, cancer cells downregulate the expression of NKG2DLs. Besides the reduction in expression, cancer cells have also been known to cleave the extracellular domain of the ligands like MIC-A/B, and such cleavage results in the release of soluble ligands. These soluble cleaved-products bind with specific NK cell receptors resulting in the neutralization of NK cell activity (Figure 2B). Intriguingly, recent reports show that MIC-A/B is stress inducible and is upregulated during cellular stress, such as oxidative stress (48) or thermal stress (49). In fact, recent experimental evidence shows that metabolic perturbation induces the expression of MIC-A/B (50). Thus, interference with tumor glycolysis and subsequent metabolic stress is a potential inducer of MIC-A/B expression, which could render cancer cells sensitive to NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity (Figure 2B).

Conclusion

Mounting evidence establish that tumor-specific alteration in energy metabolism could be the Achilles’ heel of cancer (51). It is also clear that glycolytic phenotype influences the TME. Particularly, the impediments like acidic and low pH that hinder efficacy of majority of therapeutics including infiltrating antitumor immune cells. Thus, dysregulation of tumor glycolysis has the potential to sensitize cancer cells to NK cell-mediated immunotherapy by the upregulation of stress-inducible NKG2DLs (MIC-A/B) and affect the acidity of TME rendering increased penetrability or infiltration of antitumor immune cells (Figure 2C). However, to achieve cancer-specific glycolytic dysregulation and to enhance the effectiveness of anticancer immunotherapeutics, it is imperative to overcome some major challenges. Selective inhibition of glycolysis in cancer cells but not of healthy cells is the primary requirement. In this context, recent preclinical evidences have indicated the feasibility of selective targeting of tumor glycolysis by small molecules that rely on cancer-specific upregulation transporters like MCT-1 (52, 53). Nonetheless, detailed clinical investigations are mandatory to ascertain the translational potential of such molecules and strategies. Next, emerging reports demonstrate that inhibition of glycolysis or glucose deprivation facilitates metabolic switch to OxPhos in some cancers and lead to aggressive phenotype (e.g., metastasis) (54). In such glycolytically impaired but OxPhos dependent cancer cells, therapeutic targeting of mitochondrial respiration using potential anti-mitochondrial or mitotropic agents could be a viable anticancer approach (35, 55). However, the impact of such metabolically altered phenotype in its sensitivity to anticancer immune therapeutics remains to be investigated. Nonetheless, the antiglycolytic approach-related changes in TME may still yield favorable outcomes with anticancer immune therapeutics.

Next, the dysregulation of tumor glycolysis needs to be achieved by a strategy or therapeutic that is less toxic to circumvent the problem of inadvertent or undesirable effects on NK cells’ efficacy. Similarly, one of the common causes of diminished antitumor immunity is the undesirable toxicity that emanates from prior treatments. This is prevalent in cases of prior chemotherapy as the effective dose of chemotherapy relies on maximum tolerated dose, whereas such doses are invariably toxic and affect the maturation or functional activation of immune cells (56). Thus, any agent employed to dysregulate tumor glycolysis should be sufficient to disrupt the metabolic process but not toxic. Indeed, it is preferred that such glycolytic inhibition does not kill cancer cells, as the goal is to sensitize cancer cells to immunotherapy, which in turn will enable us to expand the repertoire of antitumor immunity. Such low-dose chemotherapeutics have also been shown to enhance the effectiveness of anticancer immunotherapy (57). Thus, future studies on the selective dysregulation of tumor glycolysis to alter TME and the related therapeutic resistance could advance our ability to infiltrate and effectively target solid tumors by immunotherapeutics.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

The author gratefully acknowledges the support by Charles Wallace Pratt Research Fund.

References

- 1.Lesterhuis WJ, Haanen JB, Punt CJ. Cancer immunotherapy – revisited. Nat Rev Drug Discov (2011) 10:591–600. 10.1038/nrd3500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med (2010) 363:711–23. 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell (2011) 144:646–74. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coley WB. The treatment of inoperable sarcoma with the mixed toxins of erysipelas and Bacillus prodigiosus: immediate and final results in one hundred and forty cases. JAMA (1898) 31:389–95. 10.1001/jama.1898.92450080015001d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warburg O, Wind F, Negelein E. The metabolism of tumors in the body. J Gen Physiol (1927) 8:519–30. 10.1085/jgp.8.6.519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Husain Z, Seth P, Sukhatme VP. Tumor-derived lactate and myeloid-derived suppressor cells: linking metabolism to cancer immunology. Oncoimmunology (2013) 2:e26383. 10.4161/onci.26383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg SA. Progress in human tumour immunology and immunotherapy. Nature (2001) 411:380–4. 10.1038/35077246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kareva I, Hahnfeldt P. The emerging “hallmarks” of metabolic reprogramming and immune evasion: distinct or linked? Cancer Res (2013) 73:2737–42. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jinushi M, Vanneman M, Munshi NC, Tai YT, Prabhala RH, Ritz J, et al. MHC class I chain-related protein A antibodies and shedding are associated with the progression of multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2008) 105:1285–90. 10.1073/pnas.0711293105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho PC, Bihuniak JD, Macintyre AN, Staron M, Liu X, Amezquita R, et al. Phosphoenolpyruvate is a metabolic checkpoint of anti-tumor T cell responses. Cell (2015) 162:1217–28. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pages F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Asslaber M, Tosolini M, Bindea G, et al. In situ cytotoxic and memory T cells predict outcome in patients with early-stage colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol (2009) 27:5944–51. 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zarour HM, Ferrone S. Cancer immunotherapy: progress and challenges in the clinical setting. Eur J Immunol (2011) 41:1510–5. 10.1002/eji.201190035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rezvani K, Rouce RH. The application of natural killer cell immunotherapy for the treatment of cancer. Front Immunol (2015) 6:578. 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillerey C, Huntington ND, Smyth MJ. Targeting natural killer cells in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Immunol (2016) 17:1025–36. 10.1038/ni.3518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ljunggren HG, Malmberg KJ. Prospects for the use of NK cells in immunotherapy of human cancer. Nat Rev Immunol (2007) 7:329–39. 10.1038/nri2073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greaves M, Maley CC. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature (2012) 481:306–13. 10.1038/nature10762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang H, Qiao J, Fu YX. Immunotherapy and tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett (2016) 370:85–90. 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat Rev Cancer (2004) 4:891–9. 10.1038/nrc1478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deberardinis RJ, Sayed N, Ditsworth D, Thompson CB. Brick by brick: metabolism and tumor cell growth. Curr Opin Genet Dev (2008) 18:54–61. 10.1016/j.gde.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging of cancer with positron emission tomography. Nat Rev Cancer (2002) 2:683–93. 10.1038/nrc882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warburg O, Posener K, Negelein E. Über den Stoffwechsel der Carcinomzelle. Biochem Z (1924) 152:309–44. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward PS, Thompson CB. Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even Warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell (2012) 21:297–308. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinberg F, Hamanaka R, Wheaton WW, Weinberg S, Joseph J, Lopez M, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism and ROS generation are essential for Kras-mediated tumorigenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2010) 107:8788–93. 10.1073/pnas.1003428107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitaker-Menezes D, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Flomenberg N, Birbe RC, Witkiewicz AK, Howell A, et al. Hyperactivation of oxidative mitochondrial metabolism in epithelial cancer cells in situ: visualizing the therapeutic effects of metformin in tumor tissue. Cell Cycle (2011) 10:4047–64. 10.4161/cc.10.23.18151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhattacharya B, Mohd Omar MF, Soong R. The Warburg effect and drug resistance. Br J Pharmacol (2016) 173:970–9. 10.1111/bph.13422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suh DH, Kim HS, Kim B, Song YS. Metabolic orchestration between cancer cells and tumor microenvironment as a co-evolutionary source of chemoresistance in ovarian cancer: a therapeutic implication. Biochem Pharmacol (2014) 92:43–54. 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meijer TW, Kaanders JH, Span PN, Bussink J. Targeting hypoxia, HIF-1, and tumor glucose metabolism to improve radiotherapy efficacy. Clin Cancer Res (2012) 18:5585–94. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailey KM, Wojtkowiak JW, Hashim AI, Gillies RJ. Targeting the metabolic microenvironment of tumors. Adv Pharmacol (2012) 65:63–107. 10.1016/B978-0-12-397927-8.00004-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talekar M, Boreddy SR, Singh A, Amiji M. Tumor aerobic glycolysis: new insights into therapeutic strategies with targeted delivery. Expert Opin Biol Ther (2014) 14:1145–59. 10.1517/14712598.2014.912270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romero-Garcia S, Moreno-Altamirano MM, Prado-Garcia H, Sanchez-Garcia FJ. Lactate contribution to the tumor microenvironment: mechanisms, effects on immune cells and therapeutic relevance. Front Immunol (2016) 7:52. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiume L, Manerba M, Vettraino M, Di Stefano G. Impairment of aerobic glycolysis by inhibitors of lactic dehydrogenase hinders the growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Pharmacology (2010) 86:157–62. 10.1159/000317519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathupala SP, Ko YH, Pedersen PL. Hexokinase II: cancer’s double-edged sword acting as both facilitator and gatekeeper of malignancy when bound to mitochondria. Oncogene (2006) 25:4777–86. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganapathy-Kanniappan S, Kunjithapatham R, Geschwind JF. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase: a promising target for molecular therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget (2012) 3:940–53. 10.18632/oncotarget.623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scatena R, Bottoni P, Pontoglio A, Mastrototaro L, Giardina B. Glycolytic enzyme inhibitors in cancer treatment. Expert Opin Investig Drugs (2008) 17:1533–45. 10.1517/13543784.17.10.1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ganapathy-Kanniappan S. Targeting tumor glycolysis by a mitotropic agent. Expert Opin Ther Targets (2015) 20:1–5. 10.1517/14728222.2016.1093114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ralph SJ, Rodriguez-Enriquez S, Neuzil J, Saavedra E, Moreno-Sanchez R. The causes of cancer revisited: “mitochondrial malignancy” and ROS-induced oncogenic transformation – why mitochondria are targets for cancer therapy. Mol Aspects Med (2010) 31:145–70. 10.1016/j.mam.2010.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swietach P, Vaughan-Jones RD, Harris AL, Hulikova A. The chemistry, physiology and pathology of pH in cancer. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci (2014) 369:20130099. 10.1098/rstb.2013.0099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fantin VR, St-Pierre J, Leder P. Attenuation of LDH-A expression uncovers a link between glycolysis, mitochondrial physiology, and tumor maintenance. Cancer Cell (2006) 9:425–34. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galanis A, Pappa A, Giannakakis A, Lanitis E, Dangaj D, Sandaltzopoulos R. Reactive oxygen species and HIF-1 signalling in cancer. Cancer Lett (2008) 266:12–20. 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ganapathy-Kanniappan S, Geschwind JF, Kunjithapatham R, Buijs M, Syed LH, Rao PP, et al. 3-Bromopyruvate induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, overcomes autophagy and causes apoptosis in human HCC cell lines. Anticancer Res (2010) 30:923–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ihrlund LS, Hernlund E, Khan O, Shoshan MC. 3-Bromopyruvate as inhibitor of tumour cell energy metabolism and chemopotentiator of platinum drugs. Mol Oncol (2008) 2:94–101. 10.1016/j.molonc.2008.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao P, Zhang H, Dinavahi R, Li F, Xiang Y, Raman V, et al. HIF-dependent antitumorigenic effect of antioxidants in vivo. Cancer Cell (2007) 12:230–8. 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang CH, Qiu J, O’Sullivan D, Buck MD, Noguchi T, Curtis JD, et al. Metabolic competition in the tumor microenvironment is a driver of cancer progression. Cell (2015) 162:1229–41. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Castello-Cros R, Flomenberg N, Witkiewicz AK, Frank PG, et al. The reverse Warburg effect: aerobic glycolysis in cancer associated fibroblasts and the tumor stroma. Cell Cycle (2009) 8:3984–4001. 10.4161/cc.8.23.10238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin M, Wei H, Lu T. Targeting microenvironment in cancer therapeutics. Oncotarget (2016) 7:52575–83. 10.18632/oncotarget.9824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohashi T, Akazawa T, Aoki M, Kuze B, Mizuta K, Ito Y, et al. Dichloroacetate improves immune dysfunction caused by tumor-secreted lactic acid and increases antitumor immunoreactivity. Int J Cancer (2013) 133:1107–18. 10.1002/ijc.28114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis ZB, Felices M, Verneris MR, Miller JS. Natural killer cell adoptive transfer therapy: exploiting the first line of defense against cancer. Cancer J (2015) 21:486–91. 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamamoto K, Fujiyama Y, Andoh A, Bamba T, Okabe H. Oxidative stress increases MICA and MICB gene expression in the human colon carcinoma cell line (CaCo-2). Biochim Biophys Acta (2001) 1526:10–2. 10.1016/S0304-4165(01)00099-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dayanc BE, Bansal S, Gure AO, Gollnick SO, Repasky EA. Enhanced sensitivity of colon tumour cells to natural killer cell cytotoxicity after mild thermal stress is regulated through HSF1-mediated expression of MICA. Int J Hyperthermia (2013) 29:480–90. 10.3109/02656736.2013.821526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fu D, Geschwind JF, Karthikeyan S, Miller E, Kunjithapatham R, Wang Z, et al. Metabolic perturbation sensitizes human breast cancer to NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity by increasing the expression of MHC class I chain-related A/B. Oncoimmunology (2015) 4:e991228. 10.4161/2162402X.2014.991228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kroemer G, Pouyssegur J. Tumor cell metabolism: cancer’s Achilles’ heel. Cancer Cell (2008) 13:472–82. 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Birsoy K, Wang T, Possemato R, Yilmaz OH, Koch CE, Chen WW, et al. MCT1-mediated transport of a toxic molecule is an effective strategy for targeting glycolytic tumors. Nat Genet (2013) 45:104–8. 10.1038/ng.2471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thangaraju M, Karunakaran SK, Itagaki S, Gopal E, Elangovan S, Prasad PD, et al. Transport by SLC5A8 with subsequent inhibition of histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and HDAC3 underlies the antitumor activity of 3-bromopyruvate. Cancer (2009) 115:4655–66. 10.1002/cncr.24532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Saedeleer CJ, Porporato PE, Copetti T, Perez-Escuredo J, Payen VL, Brisson L, et al. Glucose deprivation increases monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) expression and MCT1-dependent tumor cell migration. Oncogene (2014) 33:4060–8. 10.1038/onc.2013.454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valenti D, de Bari L, Manente GA, Rossi L, Mutti L, Moro L, et al. Negative modulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by epigallocatechin-3 gallate leads to growth arrest and apoptosis in human malignant pleural mesothelioma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta (2013) 1832:2085–96. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kareva I, Waxman DJ, Lakka Klement G. Metronomic chemotherapy: an attractive alternative to maximum tolerated dose therapy that can activate anti-tumor immunity and minimize therapeutic resistance. Cancer Lett (2015) 358:100–6. 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.12.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soriani A, Iannitto ML, Ricci B, Fionda C, Malgarini G, Morrone S, et al. Reactive oxygen species- and DNA damage response-dependent NK cell activating ligand upregulation occurs at transcriptional levels and requires the transcriptional factor E2F1. J Immunol (2014) 193:950–60. 10.4049/jimmunol.1400271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]