Summary

Background

Asthma is a chronic disorder of the airways. Oxidative stress is an important part of asthma pathogenesis. It plays a crucial role in exacerbating the disease, as well as an important consequence of airways inflammation.

Aim

The present study was undertaken to investigate the lipid peroxidation and catalase activity in serum and antioxidant level in plasma of asthmatic patients and their association with lifestyle and severity of the disease.

Methods

A total of 210 subjects, 120 asthmatics and 90 healthy controls matched in respect to age, sex, lifestyle and socioeconomic status, were chosen randomly for the present study. The samples were analyzed for MDA concentration and catalase activity in serum and ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP). Statistical analysis was done using unpaired Student’s t-test, ANOVA with Duncan post hoc test and Pearson coefficient of correlation.

Results

The serum MDA was found to be significantly higher in the asthmatics as compared to healthy individuals (p<0.01) while catalase activity in serum and antioxidant level of the plasma were markedly lower in the asthmatics as compared to healthy individuals (p<0.01). A significant difference was observed in serum MDA, catalase activity and plasma antioxidant level among the patients in relation to the severity of disease. There was a marked increase in the serum MDA in the patients with longer duration of the disease (p<0.05).

Conclusions

The oxidant–antioxidant imbalance occurs in asthma leading to oxidative stress and is an important part of the asthma pathogenesis.

Keywords: asthma, antioxidants, oxidants, oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation

Kratak sadržaj

Uvod

Astma je hronično oboljenje disajnih puteva. Oksidativni stres čini važan deo u patogenezi astme. Ima presudnu ulogu u pogoršanju bolesti i predstavlja važnu posledicu upale disajnih puteva.

Ova studija je preduzeta kako bi se istražili lipidna peroksidacija i aktivnost katalaze u serumu i nivo antioksidanasa u plazmi kod bolesnika sa astmom i njihova povezanost sa životnim stilom i težinom bolesti.

Metode

Ukupno 210 ispitanika, 120 astmatičara i 90 zdravih kontrolnih ispitanika odgovarajuće starosti, pola, životnog stila i socioekonomskog statusa, nasumično je izabrano za ovu studiju. Analizom uzoraka određene su koncentracija MDA i aktivnost katalaze u serumu i primenjena je metoda FRAP (ferric reducing ability of plasma). Statistička analiza je izvršena pomoću Studentovog t testa, testa ANOVA sa Duncan post hoc testom i Pearsonove korelacije koeficijenta.

Rezultati

MDA u serumu bio je značajno viši kod astmatičara u poređenju sa zdravim ispitanicima (p<0,01), dok su aktivnost katalaze u serumu i nivo antioksidanasa u plazmi bili upadljivo niži kod astmatičara u poređenju sa zdravim ispitanicima (p<0,01). Između pacijenata je uočena značajna razlika u nivoima MDA u serumu, aktivnosti katalaze i nivoima antioksidanasa u plazmi u odnosu na težinu oboljenja. Postojao je upadljiv porast nivoa MDA u serumu kod pacijenata povezan sa dužinom bolesti (p<0,05).

Zaključak

U astmi se javlja poremećaj oksidantne–antioksidantne ravnoteže, što dovodi do oksidativnog stresa i čini važan deo patogeneze astme.

Introduction

The increasing incidence of asthma is a serious global issue especially in the urban population (1). Asthma is a major cause of chronic morbidity and mortality with an estimated 300 million people affected worldwide and the incidences have increased in the past few years (2). Asthma is characterized by chronic inflammation of the airways which involves recurrent episodes of wheezing, airflow obstruction and airways hyper-responsiveness to a variety of stimuli (3–5). Oxidative stress is defined as the damage that occurs when the oxidant level in the body overwhelms the antioxidant defense because of the increased reactive oxygen species such as superoxide radical (O2*), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hypochlorous acid (HOCl), and hydroxyl radical (OH*). The oxidative stress is an important component as well as consequence of asthma pathogenesis and various factors like age, duration and lifestyle determine the overall impact of disease. Increased production of ROS in asthma has been reported in many studies (6–9) and also that it is associated with an alteration in antioxidant activity in the lung and blood (10) and the development of airway hyper-responsiveness (11). The inflammation of the airways leads to overproduction of the reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause oxidative stress by interfering with the tissues in our body like proteins, lipids and DNA and causing dysfunction of these molecules. The ROS generate a large number of oxidative modifications in DNA including strand breaks and base oxidations (12–14). In addition, the physiological antioxidant system that is equipped to remove the oxidants is also impaired in asthma due to increased inflammation (15). Furthermore, poor diet or lifestyle and lesser intake of anti-oxidants also lead to increased oxidative stress and worsen the symptoms in the patients. The reactive oxygen species exaggerate airways inflammation by inducing many proinflammatory mediators including macrophages, neutrophils and eosinophils (16–17). The enzymatic antioxidants such as catalase present in the pulmonary fluid and interstitial spaces of the lungs and also in the blood vessels and airways help convert the potent oxidant hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to H2O thus helping to reduce systemic oxidant level. These enzymatic antioxidants have been reported to be decreased in asthmatic patients, which further aids in systemic oxidative stress (7). The increased oxidative stress can also be attributed to increased lipid peroxidation in asthmatic patients. The malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration in serum is an important biomarker tool to assess increased oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation in asthmatic patients (18–19). Further, the reduced antioxidant level in the diseased persons which exacerbates the symptoms is also important and should be considered. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) assay is a rapid and novel method to measure the total antioxidant power of plasma. The basic principle of this assay is the conversion of ferric to ferrous ion at low pH and formation of a ferrous-tripyridyltriazine (TPTZ) complex which gives blue color (20).

The present study aimed to compare the malondialdehyde and catalase activity level in serum and the ferric reducing ability of plasma between the asthmatic patients and healthy individuals. We have also studied the effects of lifestyle including smoking, drinking and dietary habits and other related factors on disease progression.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

A total of 210 subjects, 120 asthmatics and 90 healthy controls matched with respect to age, sex, lifestyle and socioeconomic status, were chosen randomly for the present study. All the patients were diagnosed with spirometry tests and clinical symptoms by a registered medical practitioner and the severity of disease was determined as per the Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines (3). The diagnosis was done on the basis of symptoms, recurrent episodes, wheezing and measuring the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and other spirometric parameters like forced vital capacity (FVC), peak expiratory flow rate (PEF) etc. For control, those individuals were selected who had no respiratory symptoms or any other illness and were not taking any drugs.

An appropriate written informed consent was taken from each subject prior to taking samples. The ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra. A detailed questionnaire was filled in by each subject to collect details regarding their sex, age, dietary habits, smoking and drinking habits and other parameters related to their lifestyle. Each patient’s clinical profile, spirometric measurements, history of allergy and treatment details were also collected. The study was carried out keeping in view the Declaration of Helsinki ethical guidelines for experiments involving humans.

Sample collection

Blood samples were drawn from the vein of the subjects by a registered medical practitioner and taken to the laboratory in plastic vials. The blood was allowed to clot for 30 minutes and then centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 15 minutes. The serum was collected and a part of it was analyzed within 24 hours. The rest of it was stored at –20 °C for use at a later stage if required. For plasma, blood was collected in K2EDTA coated vials (Becton Dickinson) and centrifuged at 2500 rpm. Analysis was done within 24 hours. All the reagents were prepared in the laboratory conditions. No commercial kit was used.

Catalase activity in serum

The catalase activity was evaluated by the method of Aebi (21) on the basis of oxidation of H2O2. The activity of catalase was measured by taking 20 μΙL serum in 4 mL of 50 mmol/L phosphate buffer (HIMEDIA) in a test tube. Then, 0.65 mL of substrate (10 mmol/L H2O2) was added and immediately read at 240 nm for 3 minutes by a UV-visible nanophotometer (IMPLEN, Germany). The results were expressed in U/mg protein.

Lipid peroxidation assay

For detecting the level of lipid peroxidation in serum, MDA concentration was analyzed using the standard protocol of Buege and Aust (22). For this, 0.1 mL sample, 0.1 mL Tris-HCl buffer, 0.1 mL FeSO4 and 0.1 mL ascorbic acid were added in a test tube, then 0.6 mL dH2O was added to make the volume 1.0 mL. It was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. Then, 1.0 mL tri-chloro acetic acid (TCA) (HIMEDIA) and 2 mL 2-thiobarbituric acid (TBA) (HIMEDIA) were added to the reaction mixture. Tubes were plugged and incubated for 15 min in boiling water. Centrifugation was done at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Readings were taken with the light pink supernatant at 532 nm against buffer blank. The concentration of MDA was calculated using the extinction coefficient of MDA-TBA complex which is 1.56 × 105 mmol/L−1 cm−1 and the results were expressed as nmoles/ml of serum.

FRAP assay

Total antioxidant power of plasma was measured by the FRAP (ferric reducing ability of plasma) assay given by Benzie and Strain (20). One hundred μL of plasma was mixed with 300 mL distilled water and 3 μL of working FRAP reagent, freshly prepared by adding 10:1:1 ratio of 300 mmol/L acetate buffer, a 10 mmol/L 2,4,6-tripyridyl-S-triazine (HIMEDIA) in 40 mmol/L HCl and 20 mmol/L FeCl3 × 6H2O (HIMEDIA). Absorbance was measured at 593 nm at zero minute after vortexing. After that, samples were placed at 37 °C in a water bath and absorbance was taken after 4 minutes. Ascorbic acid was taken as standard.

The concentration of serum MDA, catalase activity and FRAP values were determined in asthmatics and controls in relation to various correlates like sex, age group, smoking habits, dietary habits, drinking habits, drug intake, family history, duration etc.

Statistical analysis

Statistical software, SPSS v16.0 and Microsoft Excel 2007 were used for the analysis of the epidemiological data and the experimental results for all the assays conducted during the present study and for preparation of graphs. The following tests were applied: 1) unpaired Student’s t-test, 2) one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Duncan post hoc test and 3) Pearson’s correlation coefficient (2-tailed). A p<0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

The general and clinical characteristics of all the subjects are given in Table I. The average age of the subjects was 42.48 years (range 13–80 years). These were characterized for gender, age, smoking and drinking habits, dietary habits, daily physical activity and biomass exposure (use of biomass fuel). Out of 210 subjects, 97 (46.2%) were males and 113 (53.8%) were females. A significant difference (p<0.01) was observed in the spirometric measurements (FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC, PEF and FEF25–75% predicted) of the asthmatics and the healthy subjects (Table I). The serum MDA (0.75±0.08) was found to be significantly higher in the asthmatics as compared to healthy individuals (0.38±0.02, p<0.01).

Table I.

General, clinical and demographic characteristics of the subjects studied.

| Characteristics | Asthmatics | Controls | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 120 | 90 | – |

| Age (years) | 45.22±1.48 | 38.84±1.32 | – |

| Age range (years) | 13–80 | 18–67 | – |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 23.84±0.47 | 23.61±0.39 | 0.707 |

| FVC (% Predicted)** | 71.66±1.79 | 95.26±1.18 | 0.000 |

| FEV1 (% Predicted)** | 66.97±1.94 | 94.33±0.98 | 0.000 |

| FEV1/FVC (% Predicted)** | 95.40±1.37 | 104.79±0.78 | 0.000 |

| PEF (% Predicted)** | 54.27±2.11 | 80.59±1.82 | 0.000 |

| FEF 25–75 (% Predicted)** | 46.35±2.01 | 74.53±2.06 | 0.000 |

| Sex (Males/Females) | 44/76 | 53/37 | – |

| Smokers/Nonsmokers | 19/101 | 29/61 | – |

| Alcohol consumers/Abstainers | 17/103 | 25/65 | – |

| Vegetarians/Non-vegetarians | 81/39 | 53/37 | – |

| Mild to moderately active/Sedentary | 24/96 | 38/52 | – |

| Biomass smoke exposure (Exp/Non-exp) | 37/83 | 29/61 | – |

| Serum MDA (nmol/mL)** | 0.75±0.08 | 0.38±0.02 | 0.000 |

| FRAP (μmol/L)** | 367.39±9.95 | 466.67±15.52 | 0.000 |

| Catalase activity (U/mg protein)** | 0.20±0.02 | 0.30±0.02 | 0.000 |

Significant (p<0.01), unpaired Student’s t-test.

BMI – Body Mass Index, FVC – Forced Vital Capacity, FEV1 – Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 Second, PEF – Peak Expiratory Flow Rate, FEF25-75% – Forced Expiratory Flow at 25-75% in % predicted, Exp – Exposed.

The values of age, BMI, FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC, PEF and FEF 25–75 are expressed as Mean ± S.E of mean.

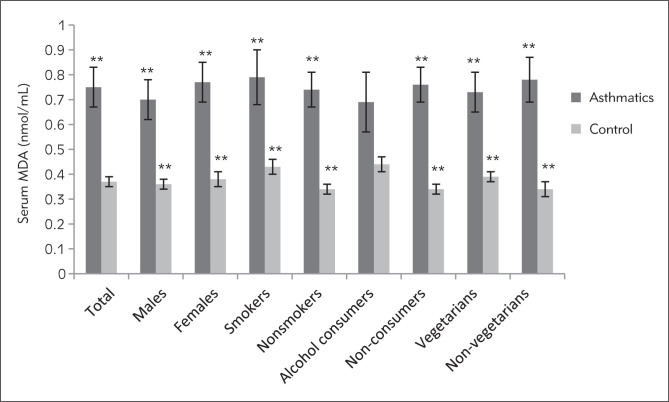

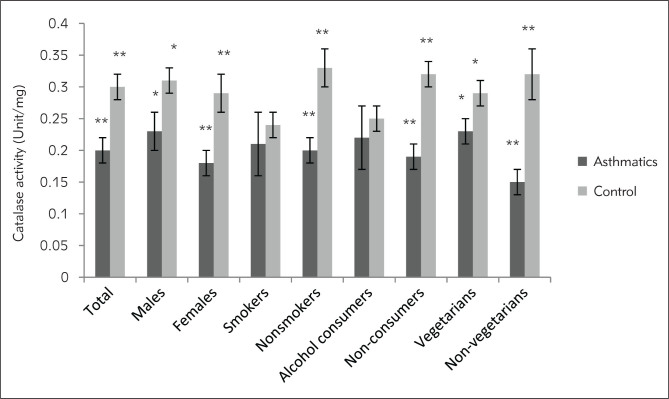

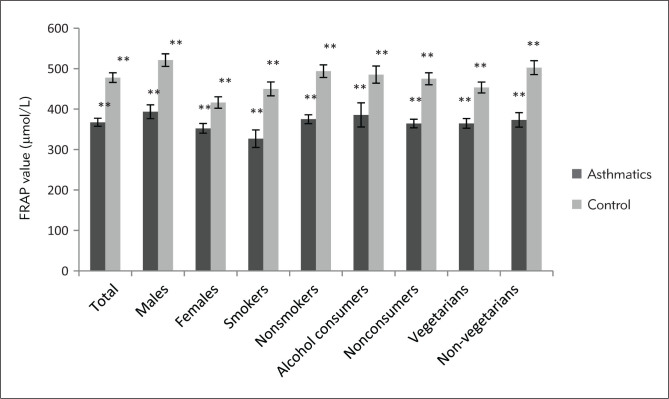

Marked differences were observed in the biochemical and spirometric parameters among the patients with different severity of disease except age, BMI and catalase activity of serum (Table II). The mean serum MDA of asthmatics was found to be significantly increasing with increased level of severity (p<0.05), whereas mean FRAP value was significantly decreasing with increased severity level (p<0.01). Markedly higher level of serum MDA was observed in all the categories of asthmatic patients as compared to the similar categories of healthy individuals except for alcohol consumers (Figure 1). The serum catalase activity was found to be significantly lower in the asthmatics as compared to healthy controls (p<0.01) in total (Table I) and in all the categories of patients except smokers and alcohol consumers (Figure 2). Total antioxidant status of the plasma was markedly lower in the asthmatics (367.39±9.95) in comparison to healthy individuals (466.67±15.52, p<0.01) in total (Table I) as well as in all the subcategories (Figure 3). Only slight differences were observed in the serum MDA, catalase activity and FRAP values among asthmatic subjects in relation to various correlates like sex, age group, smoking habits, dietary habits, drinking habits, drug intake, and family history. However, a significant difference was observed in the plasma antioxidant levels in asthmatic males and females (p<0.05). The comparison of serum MDA, catalase activity and FRAP values in asthmatics was also done in relation to number of cigarettes smoked in a day, but no significant differences were observed. Similarly, comparisons were made according to different amount of alcohol consumed in a month. Catalase activity showed no significant difference while serum MDA was found to be significantly higher in persons consuming more than 7 L in a month. The FRAP value was found to be markedly lower in the asthmatic subjects who were taking 1–7 L and more than that in a month as compared to those who were taking less than 1 L/month (Table III). No significant differences were observed in biochemical parameters with different age groups (class interval for 13–50 and 50–80 years were compared with each other) and family history (subjects with or without a family history of asthma were compared) among the asthmatic patients.

Table II.

Comparison of various parameters among patients with different severity of asthma.

| Variables | Level of asthma severity | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermittent | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| N | 18 | 34 | 30 | 38 | - |

| Age | 36.39±3.15A | 41.56±2.32AB | 46.86±2.60BC | 51.37±3.02C | - |

| BMI# | 24.10±1.23A | 24.16±0.86A | 24.04±0.88A | 23.26±0.90A | 0.874 |

| FVC** | 90.39±3.42A | 85.32±2.39B | 68.50±2.08C | 53.05±2.05C | 0.000 |

| FEV1** | 87.55±3.15A | 77.59±1.46B | 63.73±2.30C | 50.29±3.9D | 0.000 |

| FEV1/FVC** | 101.44±2.13A | 96.03±1.94B | 98.17±3.20AB | 89.79±2.71B | 0.024 |

| PEF** | 76.78±3.85A | 69.18±2.69B | 47.30±2.52C | 35.76±3.20C | 0.000 |

| FEF25-75%** | 67.89±4.84A | 57.79±2.72B | 43.47±3.44C | 28.18±2.15D | 0.000 |

| Serum MDA* | 0.36±0.05A | 0.66±0.09AB | 0.88±0.15B | 0.91±0.12B | 0.018 |

| FRAP** | 397.99±20.31A | 405.20±17.82A | 363.34±19.99AB | 322.25±17.7B | 0.006 |

| Catalase activity# | 0.25±0.06A | 0.21±0.03A | 0.21±0.04A | 0.16±0.03A | 0.487 |

The values are expressed as Mean± S.E.

The values are significantly different at 0.05 level (p<0.05), ANOVA.

The values are significantly different at 0.01 level (p<0.01), ANOVA.

The values are not significantly different.

The values with different alphabets in superscript along a row are significantly different from each other (Duncan multiple range test, 0.05 level).

The alphabets in superscript denote the significant difference, along a row; the highest value being denoted by A, lower by B and so on.

Figure 1.

MDA concentration expressed as nmol of MDA/ml of serum in asthmatic patients and controls. **Significant (p<0.01), unpaired Student’s t-test.

Figure 2.

Catalase activity in serum expressed as units/mg protein in asthmatic patients and controls. *Significant (p<0.05), **Significant (p<0.01), unpaired Student’s t-test.

Figure 3.

Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) of plasma expressed as μmol/L in asthmatic patients and controls. **Significant (p<0.01), unpaired Student’s t-test.

Table III.

Comparison of serum MDA, catalase activity and plasma antioxidant status among asthmatic subjects in relation to consumption of alcohol (all kinds) in a month.

| Consumption of alcohol | N | Specific activity of catalase (U/mg protein) | Serum MDA (nmol/mL) | FRAP value (μmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 L/month | 5 | 0.17±0.08# | 0.41±0.13B | 511.80±40.33A |

| 1–7 L/month | 6 | 0.22±0.09# | 0.53±0.06B | 359.47±35.61B |

| >7 L/month | 6 | 0.26±0.10# | 0.10±0.27A | 306.70±41.28B |

The values are expressed as Mean± S. E. Values with different alphabets in superscript along a column show significant difference (p<0.05), ANOVA with Duncan post hoc test.

The values show nonsignificant difference (p>0.05, ANOVA).

There was a remarkable negative correlation of the serum MDA with the spirometric observations, FVC (r=–0.171, p<0.05) and FEV1 (r=–0.200, p<0.05) and a positive correlation with the age (r=–0.212, p<0.05) of the patients and duration of the disease (r=0.237, p<0.05). The catalase activity of serum was slightly correlated with FVC (r=0.091) and FEV1 (r=0.083), but a markedly negative correlation was observed with duration of disease (r=-0.167, p<0.05). The total antioxidant status of the plasma exhibited a significantly positive correlation with the FVC (r=0.196, p<0.05) and FEV1 (r=0.227, p<0.01) of the patients and a significant negative correlation with duration (r=−0.210, p<0.05).

Discussion

The oxidative stress is an important constituent of asthma, where chronic inflammation leads to generation of reactive oxygen species and also exacerbates the disease. Many studies have reported elevated levels of lipid peroxidation in asthmatics especially during an acute asthmatic attack (18, 23–24). The data is inconsistent because of the varying lifestyle, dietary factors, techniques used for analysis and other factors, but overall it has been reported that the lipid peroxidation level increases with severity of disease. Rahman et al. (23) reported that the plasma MDA level was significantly higher in asthmatic patients as compared to controls and it was found to be increasing with the severity of disease. Increase in mean serum MDA level with increasing severity among asthmatic children has been reported by Al-Abdulla et al. (24). Ozaras et al. (18) studied lipid peroxidation in BAL fluid and reported that the MDA level was higher in asthmatic patients. Kanazawa et al. (25) also observed variations related to severity with acute exacerbations.

There is some evidence of lower plasma antioxidant levels in asthmatics as compared to healthy individuals. Rahman et al. (17) have reported lower antioxidant capacity of plasma in asthmatics with increased oxidative load. Ahmad et al. (26) studied MDA level, catalase activity in erythrocytes and the antioxidant level in plasma in asthmatic subjects. The study showed that the MDA level was higher while catalase activity in erythrocytes and antioxidant capacity of plasma were lower in asthmatic patients with increased severity of disease and also in comparison to healthy controls. The lower activity of catalase in the red blood cells of asthmatic patients has also been reported by Rai and Phadke (27). The present study entails that oxidant – antioxidant imbalance occurs in asthma and plays a role in disease progression. Our results are in accordance with the abovementioned studies. In the present study it was found that the MDA level was significantly higher, while catalase activity in serum and plasma antioxidant status were decreased in the asthmatic patients as compared to healthy individuals. Noticeable differences were observed for almost all the subcategories, viz males, females, smokers, nonsmokers, alcohol consumers and non-consumers, vegetarians and non-vegetarians. For example, in asthmatic smokers a significantly higher level of MDA was observed as compared to healthy smokers while the value of FRAP was significantly lower in asthmatic smokers, which indicates that smoking also affects disease pathogenesis. The increased MDA concentration and decreased FRAP value with increasing consumption of alcohol among asthmatics also imply a dose response relationship of alcohol consumption and oxidative stress among asthmatic patients. MDA was found to be noticeably increasing while plasma antioxidant was observed to be decreasing with duration and also with severity of asthma. A significant positive correlation was observed between the serum MDA and age of the asthmatic patients, which implies that age plays a critical role in oxidative stress. The age-related increase in oxidative stress has also been reported in several earlier studies (28–30). Serum MDA was also found to be positively correlated with the duration of the disease, which signifies that lipid peroxidation increases with disease progression. There was a negative correlation of serum MDA with the FVC and FEV1 of the patients which indicates that lipid peroxidation increases with the level of severity. On the other hand, the catalase activity and plasma antioxidant level were found to be negatively correlated with duration of the disease, and positively correlated with the measured FVC and FEV1 of the patients, which implies that the lower antioxidant status causes airway obstruction. Similar findings have been reported by Ahmed et al. (26).

In conclusion, the present study depicted that the oxidative stress is an important part of asthma pathogenesis. The oxidant – antioxidant imbalance which occurs in asthma plays a crucial role in disease progression and severity. This study fortifies the evidence shown by the abovementioned studies.

Acknowledgement

The present study was financially supported by Haryana State Council for Science and Technology, Panchkula (India). The authors duly acknowledge the authorities of Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra for providing the laboratory and equipment facility and HSCST for providing funds for the present study. Sincere thanks are due to Dr. Subhash Garg and Dr. Madan Khanna for their help in collection of blood samples.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors stated that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

References

- 1.Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, Besley R. The global burden of asthma: Executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee report. Allergy. 2004;59:469–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Safwat T. Towards a deep understanding of Bronchial Asthma. Egypt J Bronch. 2007;1:120. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (revised 2006): Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) http://www.ginasthma.org/local/uploads/files/GINA_Report_2010_1.pdf Available at:

- 4.Chung KF. Role of inflammation in the hyperreactivity of the airways in asthma. Thorax. 1986;41:657–62. doi: 10.1136/thx.41.9.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes PJ. Reactive oxygen species and airway inflammation. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;9:235–43. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90034-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood LJ, Gibson PG, Garg ML. Biomarkers of lipid peroxidation, airway inflammation and asthma. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:177–86. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00017003a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowler RP. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2004;4:116–22. doi: 10.1007/s11882-004-0056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caramori G, Papi A. Oxidants and asthma. Thorax. 2004;59:170–3. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2002.002477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riedl MA, Nel AE. Importance of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis and treatment of asthma. Curr Opin Allegy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:49–56. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3282f3d913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sackesen C, Ercan H, Dizdar E, Soyer O, Gumus P, Tosun BN. et al. A comprehensive evaluation of the enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidant systems in childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saleh D, Ernst P, Lim S, Barnes PJ, Giaid A. Increased formation of the potent oxidant peroxynitrite in the airways of asthmatic patients is associated with induction of NO synthase: effect of inhaled glucocorticoid. FASEB J. 1998;12:929–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cadet J, Bellon S, Berger M, Bourdat AG, Douki T, Duarte V. et al. Recent aspects of oxidative DNA damage: guanine lesions, measurement and substrate specificity of DNA repair glycosylases. Bio Chem. 2002;383:933–43. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dizdaroglu M, Jaruga P, Birincioglu M, Rodriguez H. Free radical induced damage to DNA: mechanisms and measurement. Free Radic, Bio Med. 2002;32:1102–15. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00826-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bjelland S, Seeberg E. Mutagenicity, toxicity and repair of DNA base damage induced by oxidation. Mut Res. 2003;53:137–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujisawa T. Role of oxygen radicals on bronchial asthma. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2005;4(4):505–9. doi: 10.2174/1568010054526304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henricks PA, Nijkamp FP. Reactive oxygen species as mediators in asthma. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2001;14:409–20. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2001.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman I, Morrison D, Donaldson K. Systemic oxidative stress in asthma, COPD, and smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:1055–60. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.4.8887607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozaras R, Tahan V, Turkmen S, Talay F, Besirli K, Aydin S. et al. Changes in malondialdehyde levels in bronchoalveolar fluid and serum by the treatment of asthma with inhaled steroid and beta2-agonist. Respirology. 2001;5(3):289–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2000.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadeem A, Chhabra S, Masood A. Increased oxidative stress and altered levels of antioxidants in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:72–8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benzie IF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of »antioxidant power«: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239(1):70–6. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–6. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buege JA, Aust SD. Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:302–10. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)52032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahman I, Biswas SK, Kode A. Oxidant and antioxidant balance in the airways and airways diseases. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533:222–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Abdulla NO, Al Namma LM, Hassan MK. Antioxidant status in acute asthmatic attack in children. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60(12):1023–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanazawa H, Kurihara N, Hirata K, Takeda T. The role of free radicals in airway obstruction in asthmatic patients. Chest. 1991;100:1319–22. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.5.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmad A, Shameem M, Husain Q. Relation of oxidant – antioxidant imbalance with disease progression in asthma. Ann Thoracic Med. 2012;7(4):226–32. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.102182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rai RR, Phadke MS. Plasma oxidant – antioxidant status in different respiratory disorders. Ind J Clin Biochem. 2006;21:161–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02912934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radović J, Vojinović J, Bojanić V, Jevtović-Stoimenov T, Kocić G, Milojković M, Veljković A, Marković I, Stojanović S, Pavlović D. Lipid peroxidation and oxidative protein products in children with episodic fever of unknown origin. J Med Biochem. 2014;33:197–202. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yildirism Z, Uegren NI, Yildirim F. The Role of Oxidative Stress and Anti-oxidants in the Pathogenesis of Age-related Macular Degeneration. Clinics. 2011;66(5):743–6. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000500006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cencioni C, Spallotta F, Martelli F, Vanete S, Mai A, Zeiher A. et al. Oxidative Stress and Epigenetic Regulation in Ageing and Age-related Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:17643–63. doi: 10.3390/ijms140917643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]