Abstract

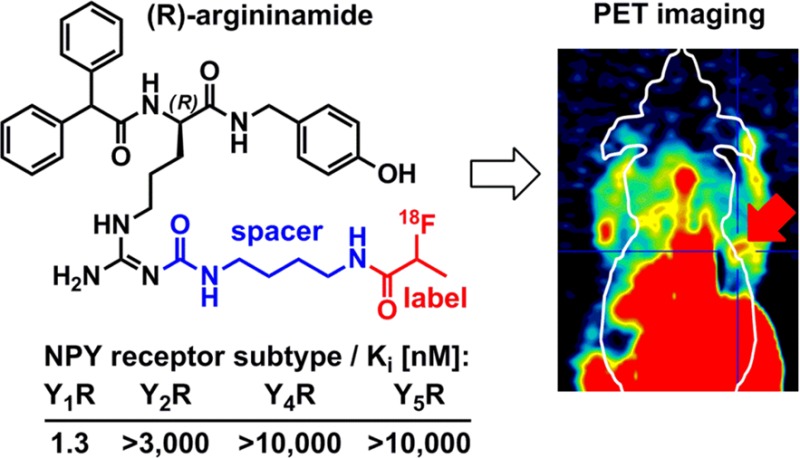

The neuropeptide Y (NPY) Y1 receptor (Y1R) selective radioligand (R)-Nα-(2,2-diphenylacetyl)-Nω-[4-(2-[18F]fluoropropanoylamino)butyl]aminocarbonyl-N-(4-hydroxybenzyl)argininamide ([18F]23), derived from the high-affinity Y1R antagonist BIBP3226, was developed for imaging studies of Y1R-positive tumors. Starting from the argininamide core bearing amine-functionalized spacer moieties, a series of fluoropropanoylated and fluorobenzoylated derivatives was synthesized and studied for Y1R affinity. The fluoropropanoylated derivative 23 displayed high affinity (Ki = 1.3 nM) and selectivity toward Y1R. Radiosynthesis was accomplished via 18F-fluoropropanoylation, yielding [18F]23 with excellent stability in mice; however, the biodistribution study revealed pronounced hepatobiliary clearance with high accumulation in the gall bladder (>100 %ID/g). Despite the unfavorable biodistribution, [18F]23 was successfully used for imaging of Y1R positive MCF-7 tumors in nude mice. Therefore, we suggest [18F]23 as a lead for the design of PET ligands with optimized physicochemical properties resulting in more favorable biodistribution and higher Y1R-dependent enrichment in mammary carcinoma.

Keywords: Fluorine-18, antagonist, positron emission tomography, PET, neuropeptide Y, NPY, Y1R

Neuropeptide Y (NPY), a 36 amino acid peptide, and NPY receptors are widely distributed in the central nervous system and in the periphery. NPY receptor mediated signaling is involved in the regulation and the modulation of numerous physiological processes. In humans, four NPY receptor subtypes, designated Y1R, Y2R, Y4R, and Y5R, are functionally expressed, all belonging to the superfamily of seven-transmembrane domain (G-protein coupled) receptors. Y1 and Y2 receptors were detected in a variety of human cancers and were, therefore, proposed as potential molecular targets for tumor diagnosis and treatment (theranostics).1−6 It was reported that 85% of mammary carcinoma are Y1R positive, whereas Y2R levels were found to be low.1 More than two-thirds of breast cancers are classified as estrogen receptor-positive, and in several studies an estrogen-dependent Y1R expression in breast cancer cells was described.7,8

Positron emission tomography (PET) allows noninvasive in vivo imaging of receptors expressed on tumors with high sensitivity and quantification of receptor densities, making PET a powerful imaging technique in diagnostic nuclear medicine, provided that appropriate radiotracers are available for in vivo use.9 As yet, efforts to develop radiolabeled Y1R ligands for tumor diagnosis were based on peptidic agonists.3,4,10−15 However, diaminopyridine-type 18F-labeled Y1R antagonists, developed as brain-penetrant tracers for Y1R imaging in rhesus monkey brain,16,17 could represent potential molecular tools for PET imaging of peripheral Y1R-expressing tumors, too. Recently, in vivo imaging of mammary carcinoma using an 18F-labeled NPY peptide analogue in MCF-7 tumor-bearing mice,18 and whole body scintimammography using a Y1R selective 99mTc-labeled peptide in humans13 were reported. In general, the use of nonpeptidic receptor ligands (antagonists) for tumor imaging has been explored in a few cases only, such as imaging of neurotensin receptor-positive tumors by 18F-labeled19 or 111In-labeled radioligands of the diarylpyrazole type.20

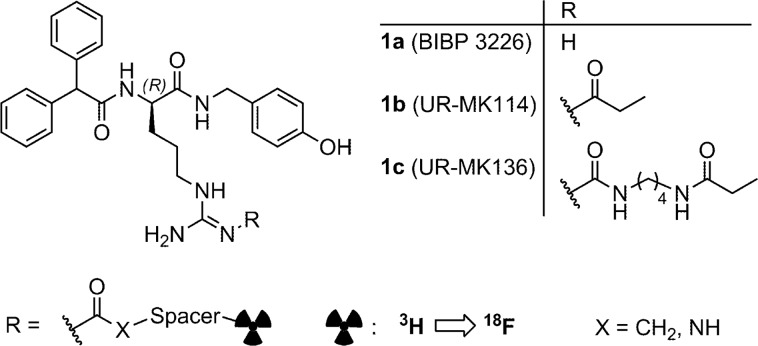

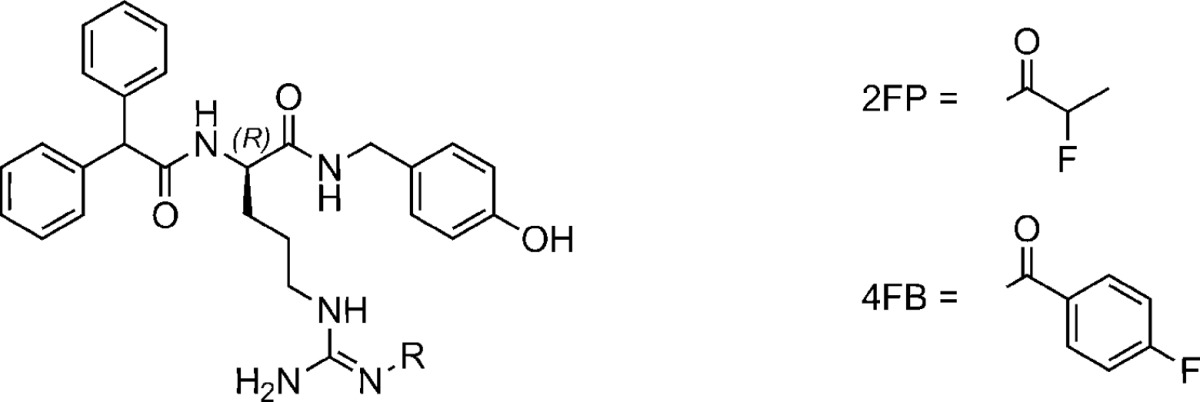

In this study we report on the exploration of 18F-labeled PET tracers for the Y1R derived from the argininamide BIBP3226 (1a, Figure 1, Table 1), a highly potent and selective Y1R antagonist.21 Lately, the bioisosteric substitution of the guanidine group in the argininamide moiety by an acyl- or carbamoylguanidine group (e.g., compounds 1b, 1c, Figure 1) was shown to be an effective strategy to prepare highly potent and selective fluorescent ligands,22,23 bivalent ligands,24−26 and tritiated radioligands for the human Y1R.27−29 Likewise, the concept of guanidine-/acylguanidine nonclassical bioisosterism has been successfully applied to Y2R selective argininamides30,31 and arginine-containing peptidic GPCR ligands.32

Figure 1.

Radiolabeled Y1R ligands derived from argininamide-type antagonists such as 1c.

Table 1. Structures and Y1R Affinities (Ki Values) of Parent Compound 1a, Amine Precursors 8, 14, 15, Alkyne 39, and Fluorinated Argininamides 4, 7, 17–26, 28, 33–36, 38, and 41; Y1R Antagonism (Kb Values) of 1a and Fluorinated Argininamides with a Ki below 100 nM; clogP Values of the Potential PET Ligands 4, 7, 17–26, 28, 33–36, 38, and 41 (Calculated with ACD/Labs 12.0 Using the Depicted Guanidine Tautomeric Form).

Dissociation constant determined from the displacement of [3H]1b (Kd = 1.2 nM, c = 1.5 nM) on SK-N-MC cells; mean values ± SEM from at least two independent experiments each performed in triplicate.

Inhibition of 10 nM pNPY induced [Ca2+]i mobilization in HEL cells; mean values ± SEM from at least two independent experiments.

Reported by Keller et al. 2011.23

Reported by Keller et al. 2008.27

Reported by Keller et al. 2011.28

Reported by Keller et al. 2013.26

clogP value was calculated for the drawn structure.

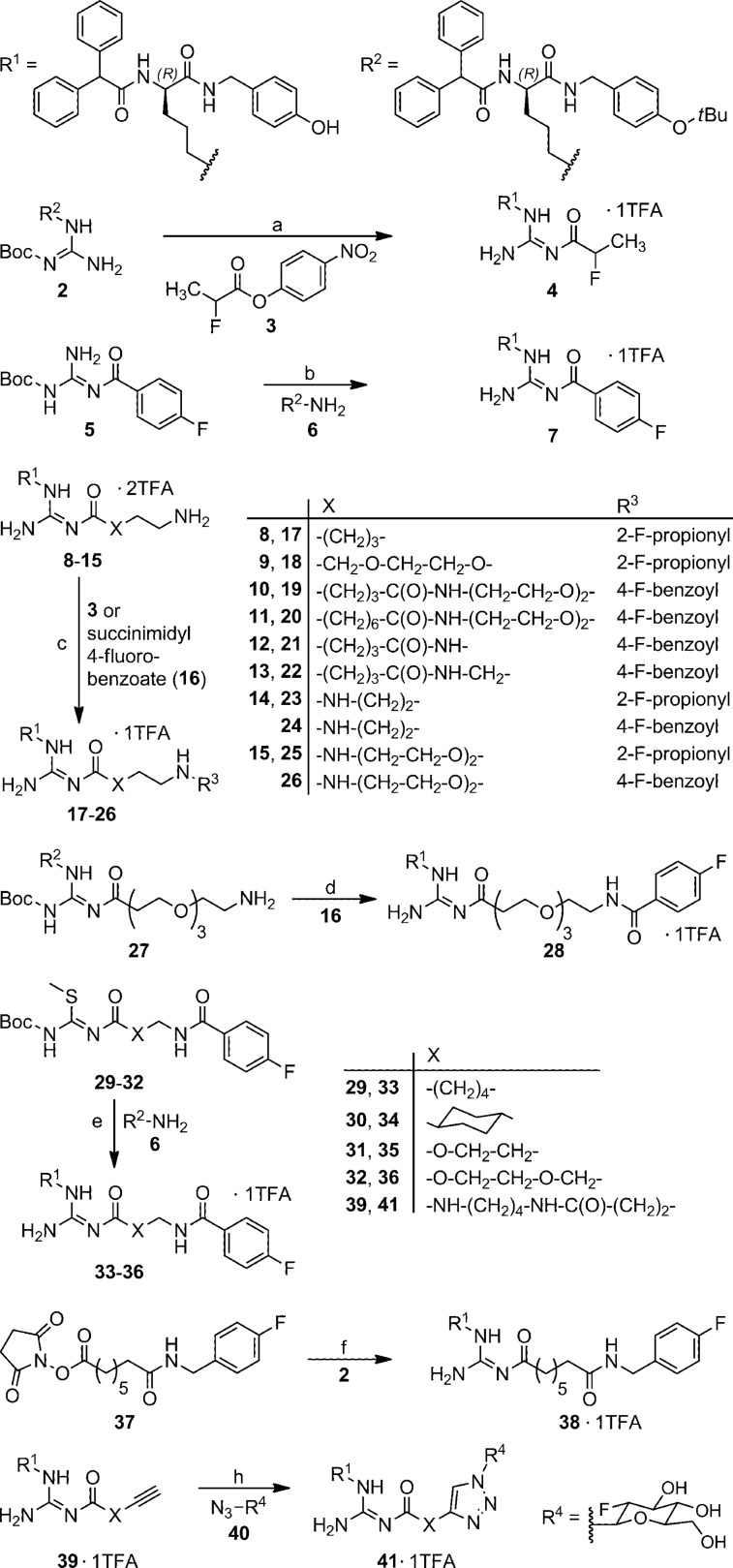

In the present study we demonstrate that this strategy of bioisosterism could be adapted to the design of fluorinated Y1R selective PET ligands. For this purpose the argininamide 1a was 2-fluoropropanoylated or 4-fluorobenzoylated either directly at the guanidine entity (compounds 4 and 7) or at an amine-functionalized spacer attached to the guanidine group (17–26, 28, 32–36) (Scheme 1). One of the early compounds was Nω-2-fluoropropionylated 1a (4), a congener of the high-affinity Y1R radioligand [3H]1b.27 In contrast to the latter,27,28 compound 4 rapidly decomposed in buffer at pH 7.4 (cf. Supporting Information) and is therefore inappropriate as a radiotracer. Whereas argininamide 4 was synthesized through acylation of compound 2(27) using 4-nitrophenyl 2-fluoropropanoate (3), the 4-fluorobenzoylated analogue 7 was obtained via activation of precursor 5 by treatment with trifluoromethanesulfonic acid anhydride and subsequent reaction with the reported amine 6 (Scheme 1).27 The majority of the series of potential PET ligands (compounds 17–26 and 28) were prepared through convenient acylation of the amine-functionalized precursor molecules 8–1523,26 and 27 with active ester 3 or 16, affording the products 17–26 and 28 with an average yield of 68% (Scheme 1). Argininamides 33–36 were obtained through guanidinylation of amine 6 with S-methylisothiourea derived guanidinylating reagents (29–32), which contained the complete Nω-substituent of the resulting argininamide (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the Fluorinated Argininamides 4, 7, 17–26, 28, 33–36, 38, and 41.

Reagents: (a) (1) triethylamine, acetonitrile; (2) TFA, acetonitrile, 84%; (b) (1) trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride, triethylamine, CH2Cl2; (2) amine 6, CH2Cl2, 40%; (c) triethylamine, acetonitrile or DMF, 48-91%; (d) (1) triethylamine, CH2Cl2; (2) TFA, CH2Cl2, 50%; (e) (1) HgCl2, triethylamine, DMF; (2) TFA, CH2Cl2, 54-85%; (f) (1) triethylamine, CH2Cl2; (2) TFA, CH2Cl2, 71%; (h) CuSO4·5H2O, sodium ascorbate, EtOH/H2O 1:1, 37%.

Compounds 38 and 41 represent potential PET ligands, which were inaccessible by 2-fluoropropionylation or 4-fluorobenzoylation. However, 38 was obtained through treatment of 2 with succinimidyl ester 37 and subsequent deprotection (Scheme 1). The triazole derivative 41 was prepared from the alkyne functionalized precursor 39 and 2-deoxy-2-fluoro-β-d-glucosyl azide (40)33 by Cu(I)-promoted “click” reaction.

The Y1R affinities of the series of argininamides were determined by displacement of [3H]1b on SK-N-MC neuroblastoma cells (Table 1). Most of the derivatives of 1a proved to be high-affinity Y1R ligands with Ki values between 1 and 65 nM. For the potential PET ligands with Ki values <100 nM (compounds 17–26, 28, 33, 34, 38) Y1R antagonism was proven in a spectrofluorimetric Fura-2 Ca2+ assay on human erythroleukemia (HEL) cells34 (Table 1). As described recently, acylation of amine precursor 14, which contains a carbamoylguanidine moiety, with tritiated propionic acid afforded a Y1R radioligand ([3H]1c, Kd = 2.0 nM).28 Likewise, acylation of 14 with 2-fluoropropionic acid gave 23, the compound with the highest Y1R affinity (Ki = 1.3 nM) among the fluorinated ligands.

Acylation of the guanidine group in 1a with 4-fluorobenzoic acid, affording 7, and the introduction of Nω-alkoxycarbonyl substituents (35, 36) resulted in compounds with considerably decreased Y1R affinity (Table 1). Even though alkyne derivative 39 showed high Y1R binding (Ki = 1.3 nM), the glucosylated derivative 41 exhibited significantly decreased Y1R affinity (Ki = 2.0 μM). Therefore, the synthesis of such fluoroglucosylated Y1R ligands as potential PET tracers was discontinued.

In addition to Y1R binding constants determined on SK-N-MC neuroblastoma cells, the Y1R affinity of compounds 18, 23, and 24 was investigated at MCF-7-Y128 breast cancer cells. The Ki values amounted to 31 ± 11, 3.3 ± 0.1, and 6.8 ± 0.5 nM, respectively, and were in good agreement with the Ki values provided in Table 1 (SK-N-MC cells). The Y1R selectivity was confirmed for argininamides 23 and 24 in flow cytometric binding studies using cyanine labeled peptides (Cy5-pNPY, Dy-635-pNPY, Cy5-[K4]hPP) and cells transfected with the human Y2, Y4, and Y5 receptor (Table S1).

According to the in vitro Y1R binding data, the 2-fluoropropionylated derivative 23 exhibited the most promising Y1R affinity among the potential PET ligands under study. In addition to receptor binding characteristics, the hydrophilicity of a PET tracer for imaging of peripheral tumors is also a critical issue with regard to the ratio between compound accumulation in the tissue of interest and elimination/excretion. The acyl- or carbamoylguanidine entity of the herein reported argininamide-type Y1R ligands exhibit a considerably lower basicity (pKa ≈ 7–8) than alkylguanidines (pKa ≈ 12–13), though high enough to account for a partial protonation of the compounds at pH 7.4 and thus sufficient water solubility (clogD(pH 7.4) < clogP). Nevertheless, the 4-fluorobenzoylated derivatives showed clogP values as high as 4.1–5.7 (Table 1), predicting unfavorable biodistribution due to high lipophilicity. The most promising derivative 23 demonstrated lower lipophilicity with a clogP value of 3.4 when compared to the series of compounds under study (Table 1).

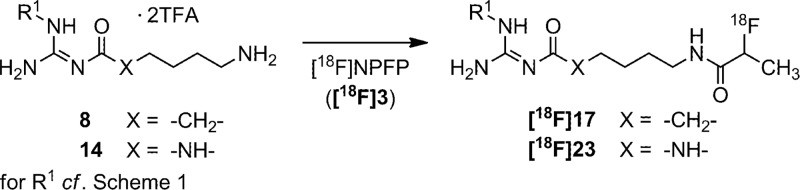

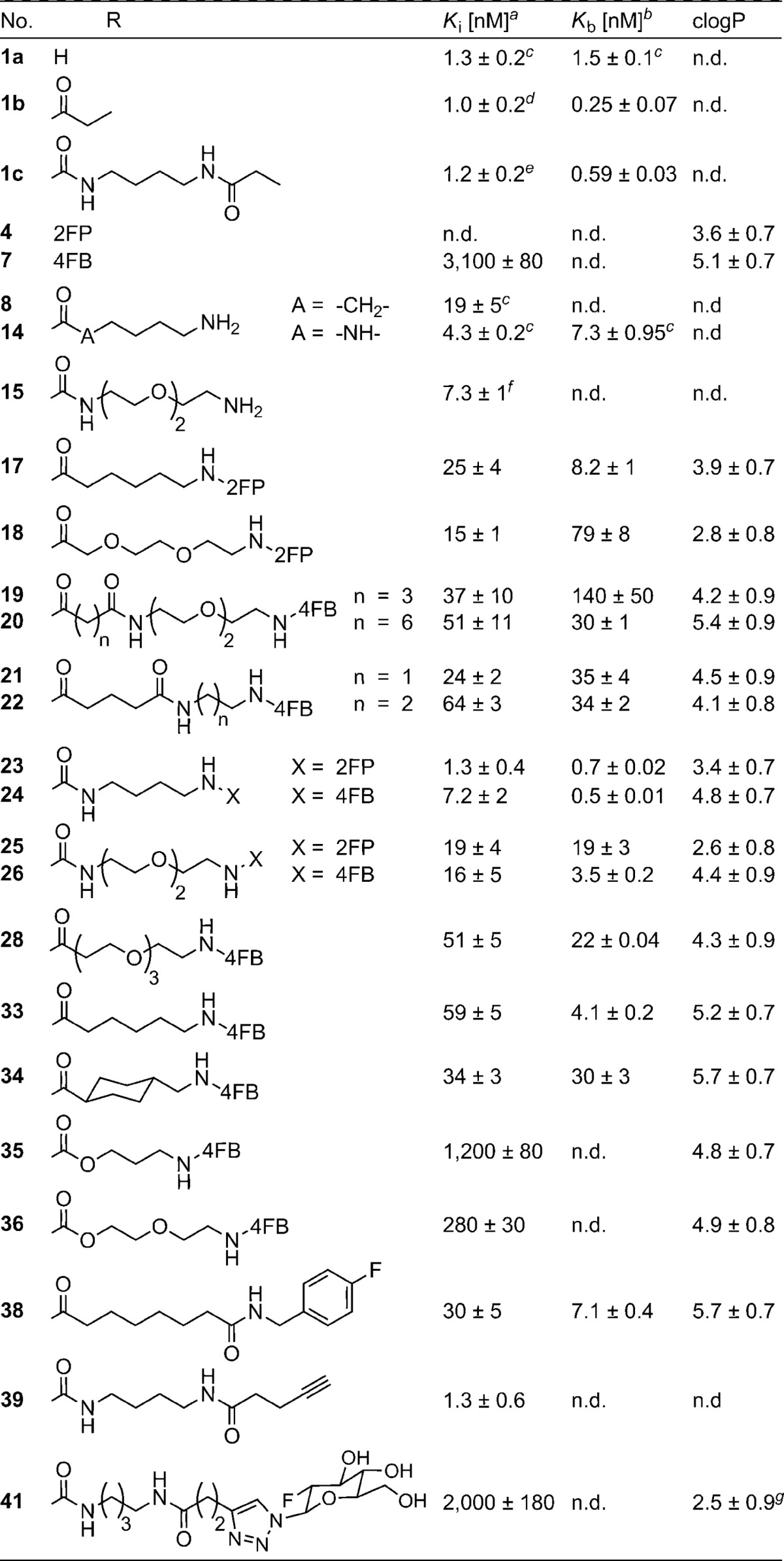

In a first approach toward a suitable PET ligand for Y1R, [18F]17 was prepared via acylation of amine precursor 8 using 4-nitrophenyl-2-[18F]fluoropropionate ([18F]NPFP, [18F]3)35 as shown in Scheme 2, and the biodistribution was studied in nude mice bearing subcutaneous SK-N-MC xenografts (Figure 2A). The radiosynthesis afforded [18F]17 in radiochemical yield (RCY) of 60% for the final reaction step, when the preliminary biodistribution study showed high uptake of [18F]17 in the gall bladder and only marginal uptake by the tumor (Figure 2A). Taking into account the highly laborious radiosynthesis of [18F]3,35 together with difficulties in the detection of the SK-N-MC tumors with [18F]17 in PET imaging experiments (results not shown), we envisaged an improved PET ligand and imaging of Y1R-positive breast cancer. The in vitro data, presented in Tables 1 and 1S, prompted us to synthesize the 18F-labeled form of 23, which has a 20-fold higher Y1R affinity compared to compound 17 (cf. Table 1). Moreover, the in vivo studies were performed with nude mice bearing MCF-7 tumors, for which we proved the expression of Y1R by immunofluorescence analysis (Figure S4, Supporting Information), confirming our previous studies.8,27,28

Scheme 2. Synthesis of the PET ligands [18F]17 and [18F]23.

Reagents and conditions: [18F]17: 1.22 μmol of 8, triethylamine, acetonitrile/DMSO 10:1, 50 °C, 15 min, RCY = 60%. [18F]23: 1.47 μmol of 14, triethylamine, acetonitrile/DMSO 11:1, 50°C, 5 min, RCY = 94%.

Figure 2.

Biodistribution data of [18F]17 (A) and [18F]23 (B) in SK-N-MC or MCF-7 tumor-bearing mice. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 3–4 mice (except for SK-N-MC tumor, n = 2).

Apart from higher Y1R affinity, 23 showed slightly higher hydrophilicity over 17 (clogP = 3.4 vs 3.9), and most importantly, 23 contains a carbamoylguanidine structure, which was recently reported to be highly stable at pH 7.4, contrary to the acylguanidine moiety of 17.23,28,32

[18F]23 was prepared by treatment of an excess of amine precursor 14 with [18F]3 (Scheme 2). [18F]3 was prepared following a previously established protocol,35 with some important modifications to optimize the overall synthesis time and RCY (Supporting Information): The 18F-fluorination of the 9′-anthrylmethyl-2-bromopropionate precursor was performed under mild reaction conditions in the presence of KH2PO4,33 resulting in a reduced precursor concentration needed for radiolabeling (30 mM instead of 116 mM35). This allowed us to omit the HPLC separation after the 18F-fluorination step and to perform the subsequent reaction steps of the radiosynthesis of [18F]3 by a simple one-pot procedure (Supporting Information). After isolation of [18F]3 by semipreparative HPLC and conjugation to amine 14, the radioligand [18F]23 was obtained in an overall RCY of 5–8% (uncorrected for decay) within an overall synthesis time of only 70–80 min and in a radiochemical purity of >99% and molar radioactivity of 12–21 GBq/μmol (n = 6).

Because [18F]23 revealed excellent in vitro Y1R binding affinity and sufficient RCY from the optimized radiosynthesis, we proceeded with the evaluation of the radioligand in vitro and in vivo using tumor-bearing nude mice with Y1R-positive MCF-7 tumors. The experimental logD7.4 determination of [18F]23 revealed a value of 2.34 ± 0.03, which differed from the calculated clogD7.4 value of 3.2 (ACD/Laboratories), possibly due to an underestimation of the protonated fraction of the ligand at physiological pH. Stability experiments in vivo displayed excellent stability of [18F]23, as no degradation products could be observed in the blood of mice at 90 min postinjection (p.i.) (Figure S2, Supporting Information).

Using MCF-7 tumor-bearing nude mice with a tumor mass of 80–240 mg, we studied whether [18F]23 could be suitable for the visualization of Y1R positive tumors. As shown in Figure 2B, [18F]23 revealed fast blood clearance in nude mice bearing MCF-7 xenografts at 30 and 90 min p.i., low uptake in the liver, but exceptionally high uptake in the gall bladder (>100 %ID/g). The biodistribution of [18F]23 was surprisingly similar to that of [18F]17 (Figure 2A). In this context, it has to be noted that these data cannot be strictly compared due to the use of different animal models.

[18F]23 showed marginally higher uptake in the intestines and lower uptake in the femur. Since decomposition of 18F-fluoropropionylated radiotracers frequently leads to increased accumulation of [18F]fluoride in the bones,36,37 the lower uptake of [18F]23 in the femur could be ascribed to the higher stability of the carbamoylguanidine as compared to the acylguanidine structure of [18F]17. The uptake of [18F]23 in MCF-7 tumors was 0.51 ± 0.04 %ID/g at 30 min p.i., and the tracer demonstrated high tumor retention with an uptake of 0.43 ± 0.08 %ID/g at 90 min p.i. (Figure 2B). Consequently, the tumor/blood ratio was about 2, also at the later time point at 90 min p.i., suggesting a suitable signal-to-noise ratio for PET imaging. In comparison with the MCF-7 tumor uptake of the previously described 18F-labeled NPY peptide analogue (0.7 %ID/g at 120 min p.i.),18 the tumor uptake of [18F]23 (0.4 %ID/g at 90 min p.i.) is lower, as the biodistribution of [18F]23 and its pronounced uptake in the gall bladder clearly hampers the suitability of [18F]23 for PET imaging purposes. However, [18F]23 revealed a significantly reduced kidney uptake by a factor of about 10 when compared with the peptide tracer, which is, as expected, the major advantage of the nonpeptide radioligand compared with a peptide ligand for PET imaging.

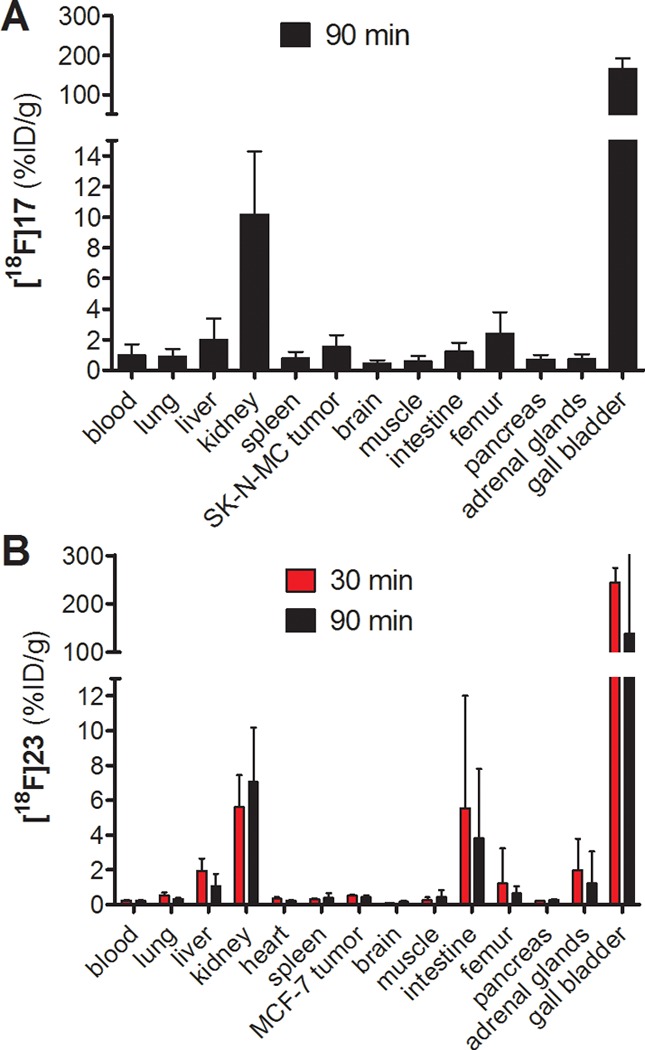

[18F]23 was injected into MCF-7 xenografted nude mice for PET imaging studies and demonstrated displaceable and specific Y1R-mediated tumor uptake (Figure 3A,B), regardless of its biodistribution with predominant accumulation in the gall bladder, intestines, and kidneys (Figure 3C). The in vivo specificity of [18F]23 was proven by coinjection of 1a (40 μg/animal, bolus injection of 100 μL over a few seconds), demonstrating a significantly diminished tracer uptake in the tumors of coinjected animals (0.42 ± 0.13 %ID/g (n = 5, Figure 3A) vs 0.21 ± 0.07 %ID/g (n = 4, Figure 3B), P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test, two-tailed). In addition, to exclude that differences in tumor uptake could be a result of overall biodistribution changes when 1a is administered prior to tracer injection, we determined tumor-to-muscle ratios by PET image analysis, confirming significantly diminished tumor uptake of [18F]23 by coinjection of 1a (3.1 ± 0.9 (n = 5, control) vs 1.8 ± 0.7 (n = 4, coinjection), P < 0.05, paired t test). These results confirmed the visualization of Y1R-positive MCF-7 tumors by the antagonist [18F]23 in vivo by PET.

Figure 3.

Representative coronal PET images of a MCF-7 tumor-bearing mouse injected with [18F]23 alone (A) or with [18F]23 and 1a (40 μg, B). The blue crosshair indicates the tumor. (C) PET image of the same mouse with adjusted scale bar showing the biodistribution of [18F]23 in the plane of the intestines (left) and in the kidneys (right): b, bladder; g, gall bladder; i, intestines; k, kidneys; l, liver.

In conclusion, we developed the antagonist radioligand [18F]23 as the first nonpeptide 18F-labeled tracer that has been evaluated for in vivo small animal PET imaging of Y1R-positive mammary carcinoma. The biodistribution of [18F]23 is characterized by its hepatobiliary clearance with very slow clearance of the gall bladder. We suggest [18F]23 as a lead for the design of improved PET ligands with more favorable biodistribution and higher Y1R-dependent tumor uptake to enable PET imaging studies. Further preclinical studies of derivatives of [18F]23 are currently underway.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Prof. Dr. Chiara Cabrele (University of Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria) for the synthesis of pNPY, to Dr. Thilo Spruss (University of Regensburg, Germany) for assisting PET and biodistribution studies, to Dr. M. Herz (Technical University Munich, Munich, Germany) for the preparation of [18F]3, to Dr. Nathalie Pop (University of Regensburg, Germany) for the determination of selectivity data, to Mrs. Elvira Schreiber (University of Regensburg, Germany) for substantial support in the determination of Y1R antagonism and selectivity data, to Mrs. Brigitte Wenzl (University of Regensburg, Germany) for substantial support in the determination of Y1R binding data, and Mrs. Susanne Bollwein and Franz Wiesenmeyer (University of Regensburg, Germany) for expert technical assistance. The authors also thank Manuel Geisthoff and Bianca Weigel (Friedrich-Alexander University (FAU), Erlangen, Germany) for expert technical support in carrying out the PET and biodistribution studies.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- brs

broad singlet

- CH2Cl2

dichloromethane

- DIPEA

diisopropylethylamine

- EDC·HCl

1-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride

- EtOAc

ethyl acetate

- HEL cells

human erythroleukemia cells

- HOBt

1-hydroxybenzotriazole

- hPP

human pancreatic polypeptide

- k

retention (or capacity) factor (HPLC)

- Kd

dissociation (or binding) constant obtained from a saturation binding experiment

- Ki

dissociation (or binding) constant obtained from a competition binding experiment

- logD7.4

logarithm of distribution coefficient (pH of the aqueous phase = 7.4)

- MeCN

acetonitrile

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- p.i.

postinjection

- pNPY

porcine NPY

- RCY

radiochemical yield

- RP-HPLC

reversed-phase HPLC

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- TBTU

2-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate

- Y1R

NPY Y1 receptor

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00467.

Experimental description of the synthesis and analytical data of compounds 3–5, 7, 16–26, 28–39, 41 and further intermediates. RP-HPLC chromatograms of compounds 4, 7, 17–26, 28, 33–36, 38, 39 and 41. Investigations on the chemical stability of 4. Pharmacology-related experimental protocols. Data on Y1R selectivity of 23 and 24. Experimental protocols for the synthesis of the PET ligands [18F]17 and [18F]23, for animal studies, PET imaging, Western blot, and immunofluorescence analysis (PDF)

Author Present Address

∥ Ascendis Pharma GmbH, Im Neuenheimer Feld 584, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany.

Author Present Address

⊥ Piramal Imaging GmbH, Tegeler Str. 7, D-13353 Berlin, Germany.

Author Contributions

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant MA 4295/1–3 and Graduate Training Programs (Graduiertenkollegs) GRK 760 (“Medicinal Chemistry: Molecular Recognition–Ligand-Receptor Interactions”) and GRK 1910 (“Medicinal Chemistry of Selective GPCR Ligands”)).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Reubi J. C.; Gugger M.; Waser B.; Schaer J. C. Y1-mediated effect of neuropeptide Y in cancer: breast carcinomas as targets. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 4636–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körner M.; Reubi J. C. NPY receptors in human cancer: a review of current knowledge. Peptides 2007, 28, 419–25. 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubi J. C.; Maecke H. R. Peptide-based probes for cancer imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2008, 49, 1735–8. 10.2967/jnumed.108.053041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwanziger D.; Beck-Sickinger A. G. Radiometal targeted tumor diagnosis and therapy with peptide hormones. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 2385–400. 10.2174/138161208785777397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C.; Everhart L.; Tilan J.; Kuo L.; Sun C. C. J.; Munivenkatappa R. B.; Joensson-Rylander A. C.; Sun J.; Kuan-Celarier A.; Li L.; Abe K.; Zukowska Z.; Toretsky J. A.; Kitlinska J. Neuropeptide Y and its Y2 receptor: potential targets in neuroblastoma therapy. Oncogene 2010, 29, 5630–5642. 10.1038/onc.2010.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgat C.; Mishra A. K.; Varshney R.; Allard M.; Fernandez P.; Hindie E. Targeting neuropeptide receptors for cancer imaging and therapy: perspectives with bombesin, neurotensin, and neuropeptide-Y receptors. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 1650–1657. 10.2967/jnumed.114.142000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlal H.; Faroqui S.; Balasubramaniam A.; Sheriff S. Estrogen up-regulates neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor expression in a human breast cancer cell line. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 3706–3714. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memminger M.; Keller M.; Lopuch M.; Pop N.; Bernhardt G.; von Angerer E.; Buschauer A. The neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor: a diagnostic marker? Expression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells is down-regulated by antiestrogens in vitro and in xenografts. PLoS One 2012, 7, e51032. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Conti P. S. Radiopharmaceutical chemistry for positron emission tomography. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2010, 62, 1031–1051. 10.1016/j.addr.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer M.; La Bella R.; Garcia-Garayoa E.; Beck-Sickinger A. G. 99mTc-Labeled Neuropeptide Y Analogues as Potential Tumor Imaging Agents. Bioconjugate Chem. 2001, 12, 1028–1034. 10.1021/bc015514h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwanziger D.; Khan I. U.; Neundorf I.; Sieger S.; Lehmann L.; Friebe M.; Dinkelborg L.; Beck-Sickinger A. G. Novel chemically modified analogues of neuropeptide Y for tumor targeting. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008, 19, 1430–8. 10.1021/bc7004297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan I. U.; Beck-Sickinger A. G. Targeted tumor diagnosis and therapy with peptide hormones as radiopharmaceuticals. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 186–99. 10.2174/187152008783497046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan I. U.; Zwanziger D.; Bohme I.; Javed M.; Naseer H.; Hyder S. W.; Beck-Sickinger A. G. Breast-cancer diagnosis by neuropeptide Y analogues: from synthesis to clinical application. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1155–8. 10.1002/anie.200905008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin B.; Dumulon-Perreault V.; Tremblay M.-C.; Ait-Mohand S.; Fournier P.; Dubuc C.; Authier S.; Benard F. [Lys(DOTA)4]BVD15, a novel and potent neuropeptide Y analog designed for Y1 receptor-targeted breast tumor imaging. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 950–953. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatenet D.; Cescato R.; Waser B.; Erchegyi J.; Rivier J. E.; Reubi J. C. Novel dimeric DOTA-coupled peptidic Y1-receptor antagonists for targeting of neuropeptide Y receptor-expressing cancers. EJNMMI Res. 2011, 1, 21. 10.1186/2191-219X-1-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameda M.; Ando M.; Nakama C.; Kobayashi K.; Kawamoto H.; Ito S.; Suzuki T.; Tani T.; Ozaki S.; Tokita S.; Sato N. Synthesis and evaluation of a series of 2,4-diaminopyridine derivatives as potential positron emission tomography tracers for neuropeptide Y Y1 receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 5124–5127. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler E. D.; Sanabria-Bohorquez S.; Fan H.; Zeng Z.; Gantert L.; Williams M.; Miller P.; O’Malley S.; Kameda M.; Ando M.; Sato N.; Ozaki S.; Tokita S.; Ohta H.; Williams D.; Sur C.; Cook J. J.; Burns H. D.; Hargreaves R. Synthesis, characterization, and monkey positron emission tomography (PET) studies of [18F]Y1–973, a PET tracer for the neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor. NeuroImage 2011, 54, 2635–2642. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann S.; Maschauer S.; Kuwert T.; Beck-Sickinger A. G.; Prante O. Synthesis and in Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of an 18F-Labeled Neuropeptide Y Analogue for Imaging of Breast Cancer by PET. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2015, 12, 1121–1130. 10.1021/mp500601z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang C.; Maschauer S.; Hübner H.; Gmeiner P.; Prante O. Synthesis and evaluation of a 18F-labeled diarylpyrazole glycoconjugate for the imaging of NTS1-positive tumors. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 9361–9365. 10.1021/jm401491e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz J.; Rohracker M.; Stiebler M.; Grosser O. S.; Pethe A.; Goldschmidt J.; Osterkamp F.; Reineke U.; Smerling C.; Amthauer H. Comparative Evaluation of the Biodistribution Profiles of a Series of Nonpeptidic Neurotensin Receptor-1 Antagonists Reveals a Promising Candidate for Theranostic Applications. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 1120–3. 10.2967/jnumed.115.170530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolf K.; Eberlein W.; Engel W.; Wieland H. A.; Willim K. D.; Entzeroth M.; Wienen W.; Beck-Sickinger A. G.; Doods H. N. The first highly potent and selective non-peptide neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor antagonist: BIBP3226. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994, 271, R11–3. 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90822-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider E.; Keller M.; Brennauer A.; Hoefelschweiger B. K.; Gross D.; Wolfbeis O. S.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A. Synthesis and characterization of the first fluorescent nonpeptide NPY Y1 receptor antagonist. ChemBioChem 2007, 8, 1981–8. 10.1002/cbic.200700302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M.; Erdmann D.; Pop N.; Pluym N.; Teng S.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A. Red-fluorescent argininamide-type NPY Y1 receptor antagonists as pharmacological tools. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 2859–2878. 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S.; Keller M.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A.; Koenig B. Modular synthesis of non-peptidic bivalent NPY Y1 receptor antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 9858–9866. 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M.; Teng S.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A. Bivalent Argininamide-Type Neuropeptide Y Y1 Antagonists Do Not Support the Hypothesis of Receptor Dimerization. ChemMedChem 2009, 4, 1733–1745. 10.1002/cmdc.200900213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M.; Kaske M.; Holzammer T.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A. Dimeric argininamide-type neuropeptide Y receptor antagonists: chiral discrimination between Y1 and Y4 receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 6303–6322. 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M.; Pop N.; Hutzler C.; Beck-Sickinger A. G.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A. Guanidine-Acylguanidine Bioisosteric Approach in the Design of Radioligands: Synthesis of a Tritium-Labeled NG-Propionylargininamide ([3H]-UR-MK114) as a Highly Potent and Selective Neuropeptide Y Y1 Receptor Antagonist. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 8168–8172. 10.1021/jm801018u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A. [3H]UR-MK136: A Highly Potent and Selective Radioligand for Neuropeptide Y Y1 Receptors. ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 1566–1571. 10.1002/cmdc.201100197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M.; Weiss S.; Hutzler C.; Kuhn K. K.; Mollereau C.; Dukorn S.; Schindler L.; Bernhardt G.; Koenig B.; Buschauer A. Nω-Carbamoylation of the argininamide moiety: an avenue to insurmountable NPY Y1 receptor antagonists and a radiolabeled selective high-affinity molecular tool ([3H]UR-MK299) with extended residence time. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 8834–8849. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluym N.; Brennauer A.; Keller M.; Ziemek R.; Pop N.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A. Application of the Guanidine-Acylguanidine Bioisosteric Approach to Argininamide-Type NPY Y2 Receptor Antagonists. ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 1727–1738. 10.1002/cmdc.201100241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluym N.; Baumeister P.; Keller M.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A. [3H]UR-PLN196: a selective nonpeptide radioligand and insurmountable antagonist for the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor. ChemMedChem 2013, 8, 587–593. 10.1002/cmdc.201200566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M.; Kuhn K. K.; Einsiedel J.; Huebner H.; Biselli S.; Mollereau C.; Wifling D.; Svobodova J.; Bernhardt G.; Cabrele C.; Vanderheyden P. M. L.; Gmeiner P.; Buschauer A. Mimicking of Arginine by Functionalized Nω-Carbamoylated Arginine As a New Broadly Applicable Approach to Labeled Bioactive Peptides: High Affinity Angiotensin, Neuropeptide Y, Neuropeptide FF, and Neurotensin Receptor Ligands As Examples. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 1925–1945. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschauer S.; Prante O. A series of 2-O-trifluoromethylsulfonyl-D-mannopyranosides as precursors for concomitant 18F-labeling and glycosylation by click chemistry. Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344, 753–761. 10.1016/j.carres.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M.; Knieps S.; Gessele K.; Dove S.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A. Synthesis and neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor antagonistic activity of N,N-disubstituted omega-guanidino- and omega-aminoalkanoic acid amides. Arch. Pharm. 1997, 330, 333–42. 10.1002/ardp.19973301104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wester H.-J.; Hamacher K.; Stöcklin G. A comparative study of n.c.a. fluorine-18 labeling of proteins via acylation and photochemical conjugation. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1996, 23, 365–372. 10.1016/0969-8051(96)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M.; Naka K.; Kitagawa Y.; Ishiwata K.; Yoshimoto M.; Shimizu I.; Toyohara J. Synthesis and evaluation of 7alpha-(3-[18F]fluoropropyl) estradiol. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2015, 42, 590–7. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchar M.; Mamat C. Methods to Increase the Metabolic Stability of 18F-Radiotracers. Molecules 2015, 20, 16186–220. 10.3390/molecules200916186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.