Abstract

Homo sapiens harbor two distinct, medically significant species of simplexviruses, herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1 and HSV-2, with estimated divergence 6–8 million years ago (MYA). Unexpectedly, we found that circulating HSV-2 strains can contain HSV-1 DNA segments in three distinct genes. Using over 150 genital swabs from North and South America and Africa, we detected recombinants worldwide. Common, widely distributed gene UL39 genotypes are parsimoniously explained by an initial >457 basepair (bp) HSV-1 × HSV-2 crossover followed by back-recombination to HSV-2. Blocks of >244 and >539 bp of HSV-1 DNA within genes UL29 and UL30, respectively, have reached near fixation, with a minority of strains retaining sequences we posit as ancestral HSV-2. Our data add to previous in vitro and animal work, implying that in vivo cellular co-infection with HSV-1 and HSV-2 yields viable interspecies recombinants in the natural human host.

Herpes simplex viruses types 1 and 2 are Simplexviruses in the Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily and are important pathogens with a natural host range restricted to humans. Herpesviruses have single-segment, linear DS DNA genomes and low mutation rates. Uniquely among primates, humans are known to harbor two Simplexviruses, each bearing homologous sets of approximately 74 open reading frames (ORFs). HSV-1/HSV-2 amino acid identity ranges from 43.5% for US5, encoding a glycoprotein, to 92% of UL29, encoding a DNA binding protein. It has been estimated that HSV-1 and HSV-2 diverged 6–8 million years ago1. HSV-1 shows orolabial tropism while HSV-2 causes most recurrent genital disease, although either can infect trigeminal or lumbosacral ganglia. Loci responsible for type-specific phenotypes can be mapped with HSV-1 × HSV-2 chimeras2,3. HSV-1 × HSV-2 recombination allows outgrowth of stable interspecies recombinant viruses (IRV) in vitro. Purposeful co-infection of animals with HSV-1 and HSV-2 can also yield recombinants, but they have not previously been reported in humans. Sequence patterns are consistent with recombination between HSV-1 strains, and between HSV-2 strains4, but there is little data concerning HSV-1 × HSV-2 IRV in the natural host. ChHV, isolated from Pan trogdolytes, is closer to HSV-2 than is HSV-1 across the genome, and is estimated to have diverged from HSV-2 < 2 million years ago1. It has been proposed that HSV-2 and ChHV have recombined5, but the contribution of intra- and inter-species recombination to contemporary HSV diversity is unclear.

Viral recombination can be clinically significant. Equine herpesvirus (EHV)-1 recombination with EHV-4 and EHV-9, distinct species, is associated with increased host range6. Vaccine × wild-type IRV occur in herpesviruses, parvoviruses, and coronaviruses7,8 and contribute to paralytic polio. Circulating, virulent strains of infectious laryngotracheitis virus, an alphaherpesvirus, descend from vaccine strains via recombination8,9. Replication-competent HSV-1 expressing GM-CSF is a licensed melanoma therapeutic, and HSV strains are in active study as vaccines, oncolytic, and gene therapy vectors10,11. The high worldwide seroprevalence of HSV-1 and HSV-212 raises the possibility of recombination between these viruses and wild-type HSV, either within or across the HSV-1/HSV-2 divide.

We studied HSV-2 strains from North and South America and Africa, sequencing directly from genital swabs. We find that HSV-2 strains bear evidence of recombination events between HSV-1 and HSV-2 within genes UL39, UL29, and UL30. Most HSV-2 UL29 and UL30 sequences contain tracts of HSV-1 DNA, while rare specimens lack these HSV-1 recombination events. The HSV genes with interspecies recombination influence nucleotide metabolism, virulence, and sensitivity to antiviral drugs.

Results

Participants and specimens

We studied genital specimens from Seattle and Portland, USA, and sites in Peru and western, eastern, and southern Africa. The source natural history and clinical trials are detailed Methods. Initially, we newly analyzed swab specimens from unique persons by NGS (ref. 13, Genbank KX574860 through KX574908). After observing evidence of HSV-1 × HSV-2 IRV and confirmation by manual sequencing (below), we newly obtained UL39 genotyping data from 111 other persons (Table 1). The criteria for additional specimen selection was to increase coverage to about 50 persons each in North and South American and Africa, and to maintain sex and HIV co-infection status distribution within geographic areas. Persons with HIV co-infection were relatively underrepresented in the US compared to South American and Africa. We used digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) (Supporting Information Methods) to genotype additional specimens. ddPCR was validated with specimens pre-sequenced by NGS and/or Sanger methods. The absolute fluorescence intensities for HSV-1 and HSV-2 genotypes varied between runs, but inclusion of samples with known genotypes in each ddPCR run permitted genotype assignment (examples, SI Fig. 1). One or both UL39 ddPCR assays failed for 9% of genital swab DNA specimens, correlating with low amounts of HSV-2 DNA in a quantitative PCR test. Overall, we obtained unambiguous UL39 genotyping data from 152 (91%) of 167 persons on whom it was attempted.

Table 1. Participants contributing specimens for UL39 genotyping1.

| Continent | Persons2 | Sex |

HIV-1 infection |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Unknown | Positive | Negative | Unknown | ||

| Prior reports3 | |||||||

| North America | 9 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 2 |

| South America | |||||||

| Africa4 | 16 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 3 |

| Asia | 8 | 8 | 8 | ||||

| unknown | 8 | 8 | 8 | ||||

| subtotal | 41 | 6 | 13 | 22 | 6 | 14 | 21 |

| Newly reported | |||||||

| North America | 46 | 22 | 24 | 9 | 37 | ||

| South America | 50 | 19 | 30 | 1 | 33 | 17 | |

| Africa | 56 | 26 | 30 | 37 | 19 | ||

| subtotal | 152 | 67 | 84 | 1 | 79 | 73 | |

| All reported | |||||||

| North America | 55 | 24 | 29 | 2 | 10 | 43 | 2 |

| South America | 50 | 19 | 30 | 1 | 33 | 17 | |

| Africa | 72 | 30 | 38 | 4 | 42 | 27 | 3 |

| Asia | 8 | 8 | 8 | ||||

| unknown | 8 | 8 | 8 | ||||

| Total | 193 | 73 | 97 | 23 | 85 | 87 | 21 |

1Each individual with UL39 genotyping information is listed only once regardless of the presence or absence of detection of dual strain infection.

2No entry is made for values of zero participants in the indicated demographic groups.

3Includes laboratory strain HG52, 333, and 186, strains SD90e and SD6615, and strains from Brandt et al.16.

4Includes strains SD90e and SD66.

Our final data set (Table 1) incorporated all previously available UL39 sequences (SI Table 1) with the NGS and ddPCR samples newly analyzed for this report. These sequences included sequence from 31 separate persons studied14 by NGS from cultured HSV-2 isolates, all with geographic information, but some lacking sex and/or HIV infection data. We added analysis of 3 laboratory strains, 2 strains from South Africa15, and 5 reported by Kolb et al.16 with limited demographics. Overall, the UL39 analyses combined newly and previously reported from specimens from 193 persons, amongst whom 28%, 26%, and 37%, respectively, are from North America, South America, and Africa, with a few from Asia or of unknown origin. Men comprised 38% of the cohort with 50% women and 12% unknown, while 44% were HIV-1 infected, 45% HIV-1 uninfected, and 11% unknown.

Detection of HSV-1 × HSV-2 IRV

UL39 encodes the HSV large subunit of ribonucleotide reductase. We aligned 85 full-length HSV-2 UL39 sequences, including present and prior NGS data14,15,16, Genbank, and in-house resequencing. The maximum nucleotide distance was 0.0183. Length varied from 1,141 to 1,146 AA/3,423 to 3,438 nucleotides (SI Table 2). Relative to the commonest 1,444 AA length in strain 186, strains SD90e15 and G had identical 3 AA deletions, strain HG52 had a 2 AA deletion, and Ugandan strain D3965014 had a 2 AA insertion. Indels were in the UL39 N-terminus. HSV-1 UL39 sequences (n = 82, Genbank) were each 1,137 AA long and had lower 0.006 aximum nucleotide distance. HSV-1 17+17 was used for further analyses.

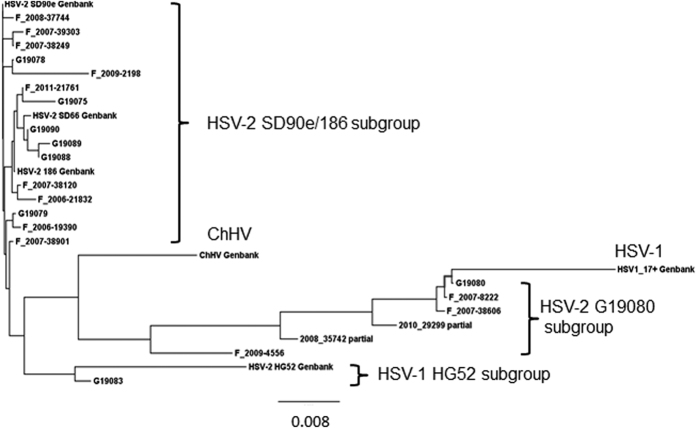

We constructed UL39 phylogenetic trees from HSV-2, HSV-1 17+ , and the ChHV homolog. Across the entire gene, the larger of the two major branches (SI Fig. 2) contained HSV-2 SD90e and laboratory strain 186. These data support the recent suggestion15,18 to use SD90e as the prototype HSV-2 strain, rather than strain HG52 (see below), and we named the largest UL39 group SD90e/186. We did use strain 186 rather than SD90e for recombination analyses herein, because strain SD90e has a very rare 9 nucleotide deletion in UL39 (above), while overall 81/85 strains (95%), including strain 186 had the same, prevalent length for UL39. Laboratory strain HG52 clearly fell in the minor UL39 branch. HSV-1 and ChHV segregated outside of these major HSV-2 groups, with ChHV closer to HSV-2 than HSV-1 from HSV-2. Aside from low prevalence SNPs and short indels, we noticed that the prevalent differences between UL39 sequences were concentrated in the 3′ region of the ORF. We therefore re-analyzed from base pair (bp) 950 to the stop codon (Fig. 1) to focus on the divergent region. To simplify, we present data for the 26 HSV-2 unique sequences in this region, excluding identical sequences. The HSV-2 SD90e/186 group was again the largest. The minor group now resolved more clearly into two subgroups. One subgroup, designated HG52, included 8 of 85 strains (9.4% of total). The second subgroup contained 15 of 85 (17.6%) sequences and was designated G19080 (SI Table 1) after a representative member. G19080 was isolated from a 45 year old HIV-1 co-infected US woman (Genbank KR13530814). Notably, both the HG52 and G19080 HSV-2 subgroups segregated with HSV-1, while ChHV again segregated separately.

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree of HSV-2 UL39 sequences from bp 950 to the stop codon.

The tree contains only one representative sequence for each unique nucleotide sequences in this region. Strain 333 is not included because it’s sequence is identical to SD90e in this region. Major subgroups, HSV-1 strain 17+, ChHV, and prototype strains from Genbank are identified. The largest HSV-2 group is contains the proposed prototype SD90e strain and strain 186, used for crossover analyses as described in the text.

Segregation of some HSV-2 UL39 genes with HSV-1 (Fig. 1) could reflect continuous or discontinuous HSV-1 UL39 alleles. Sequence alignments revealed blocks of contiguous HSV-1 markers in the HG52 and G19080 subgroups (Fig. 2A, SI Table 3). The G19080 subgroup contained a HSV-1 DNA segment of at least 457 bp as defined by flanking 5′ and 3′ HSV-1 alleles (Table 2). The flanking HSV-2 type-specific alleles were located 12 and 72 bp further in the 5′ and 3′ directions, respectively. The exact crossover loci were ambiguous given the zones of HSV-1/HSV-2 sequence identity between type-specific alleles.

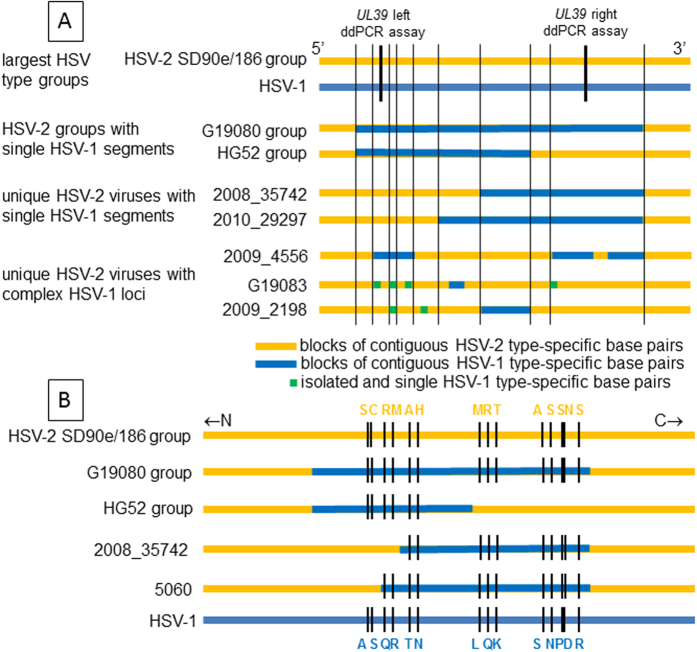

Figure 2. HSV UL39 variants in circulating strains.

Horizontal lines represent C-terminal UL39 sequences to approximate scale. Group and virus names at left. (A) Genotypes. At top, the largest HSV-2 clade similar to strains SD90e and 186 (top) is yellow and the HSV-1 group is blue. Within IRV, blue bars represent zones of 4 or more contiguous HSV-1 variant SNPs. Green spots are isolated SNPs containing one HSV-1 variant nucleotide. Thin vertical black lines represent short crossover zones indistinguishable between HSV genotypes. Thick vertical black lines show approximate locations of type-specific ddPCR genotyping assays. (B) Amino acid variations in selected groups and viruses. Strains SD90e and 186 (top) are yellow and HSV-1 group (bottom) is blue. Blue bars in IRV represent zones of contiguous SNPS with HSV-1 variant nucleotides. Short black lines represent locations of color coded amino acid differences between strains.

Table 2. Characteristics of circulating HSV-2 genotypes with HSV-1 DNA inserts.

| Gene | Strain1 | 5′ HSV-2 marker2 | 5′ HSV-1 marker3 | 3′ HSV-1 marker3 | 3′ HSV-2 marker2 | Minimum HSV-1 insert length4 | Sample origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UL39 | SD90e | A2370 | NA5 | NA | C2911 | NA | N America |

| UL39 | G19080 | A2370 | C2365 | G2821 | C2911 | 457 | N America |

| UL39 | HG52 | A2370 | C2365 | C2536 | C2617 | 172 | Europe |

| UL39 | 2008_35742 | A2554 | A2548 | G2821 | C2911 | 274 | N America |

| UL39 | 2010_29297 | C2455 | A2465 | G2821 | C2911 | 357 | N America |

| UL29 | 2009_4556 | G2181 | NA | NA | C2451 | NA | Kenya |

| UL29 | SD90e | G2181 | G2196 | A2439 | C2451 | 244 | N America |

| UL30 | 5073_9333 | C2859 | NA | NA | G3444 | NA | Kenya |

| UL30 | SD90e | C2859 | C2856 | T3394 | G3444 | 539 | N America |

1Proposed index strain for subgroup. Representative strain if several have the same pattern.

2Nucleotide number of HSV-2-specific base in HSV-2 strain 186 numbered from ATG start in relevant gene.

3Nucleotide number of HSV-1-specific base in HSV-1 strain 17+ numbered from ATG start in relevant gene.

4Minimum number of HSV-1 nucleotides present in the indicated HSV-2 strain.

5Not Applicable.

Every HG52 and G19080 subgroup virus had identical 5′ and 3′ crossover boundaries. Remarkably, the 5′ crossover marks for the HG52 and G19080 IRV subgroups were also identical (Table 2). The HG52 subgroup included bp 2,572 of HSV-1 as the 3′ flanking HSV-1 allele, for a minimum 224 bp HSV-1 insert. These IRV had considerable UL39 amino acid variation from strain 186 (Fig. 2B) in addition to nucleotide differences.

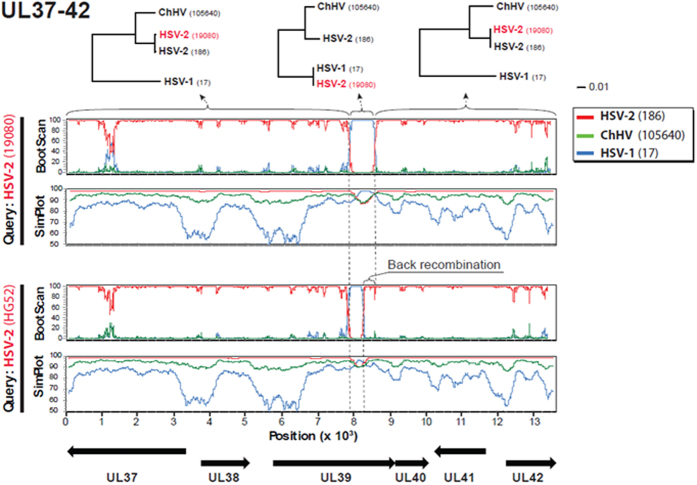

We performed formal recombination analyses on HSV genome segments from UL37 through UL42 using HSV-1 17+ and HSV-2 186, G19080, and HG52 as representative strains. The bootscan algorithm readily identified crossover points with highly significant shifting (Fig. 3) coinciding with sequence inspection (SI Table 3). The three phylogenetic trees based on the recombinant fragment and the two flanking regions clearly demonstrated a shift in topology, where the recombinant HSV-2 strain 19080 clustered closely to HSV-1 in the tree representing the recombinant fragment, while clustering closely to the HSV-2 strain 186 in the flanking regions (Fig. 3). The high similarity between the HSV-2 strain 19080 and HSV-1 in the recombinant fragment was also shown by Simplot analysis. Similar results for a shorter recombinant fragment were observed for HSV-2 strain HG52 (Fig. 3). The phi-statistics for the presence of recombination had p-values of 0.0 for both HSV-2 strains G19080 and HG52, and the algorithms implemented in RDP419 (i.e. RDP, GENECONV, bootScan, MaxChi, Chimaera, and SiScan) all yielded p-values supporting recombination (ranging from 2.7 × 10−71 to 3.2 × 10−13, and from 2.0 × 10−41 to 2.0 × 10−07 for G19080 and HG52, respectively). ChHV was included and no areas of significant recombination included this strain (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Recombination analysis of the UL37 to UL42 genomic region in HSV-2 strains 19080 (upper) and HG52 (lower).

Bootscan and a Simplot analyses are depicted for each strain. At bottom the coding directions of the ORFs and length of the genomic region in kilobases from the stop codons in UL37 and UL42 are indicated. Clear shifts in bootstrap values supporting different phylogenetic topologies indicate recombination crossovers in the UL39 gene in both strains (also indicated by vertical dotted lines). These crossovers are supported by the Simplot analysis, which demonstrates a shift in similarity with a higher similarity to HSV-1 in the recombination fragment. To further test and visualize ancestry of the recombination fragment in strain 19080, phylogenetic trees based on the recombination fragment and flanking regions are shown. Strain 19080 clearly clusters closely to HSV-1 in the tree based on the recombination fragment, and closely to HSV-2 in the flanking regions, further supporting recombination with HSV-2 as major parental, and HSV-1 as minor parental strains. The shorter recombination fragment in HSV-2 strain HG52 suggests a back recombination, where a strain with the larger HSV-1 recombination fragment has recombined again with another HSV-2 strain and expelled a part of the recombinant fragment.

Rare UL39 IRV genotypes

We used a ddPCR assay (loci schematized in Fig. 2) to rapidly genotype additional samples (Supplementary Methods, SI Table 4 for methods; sample data in SI Fig. 1). Strains HSV-1 17+ , HSV-2 G19080, HSV-2 HG52, and HSV-2 186 had the predicted HSV1:HSV1, HSV1:HSV1, HSV2:HSV1, and HSV2:HSV2 genotypes at the 5′ and 3′ UL39 loci respectively. Most swab-derived DNA specimens had one of these genotype patterns. A new HSV1:HSV2 ddPCR pattern, consistent with additional UL39 IRV, was detected in in two HIV-uninfected participants (samples 2010_29297 and 2008_35742) (Fig. 2, SI Fig. 1). For participant 5060 who donated sample 2010_29297, 11 swabs collected over 37 days had this ddPCR genotype.

Sanger sequencing (SI tables 5 and 6) confirmed the ddPCR data and defined two additional UL39 IRV genotypes. Each had 3′ crossover markers identical to G19080 (SI Table 3, Fig. 2A) and novel 5′ crossovers internal to the long G19080 HSV-1 insert. Sample 2008_35742 had a longer HSV-1 insert than sample 2010_29297, containing 11 additional HSV-1 type-specific allelic variant markers and extending a minimum of 77 bp further in the 5′ direction within UL39. Bootscan, Simplot and phylogenetic analyses again were highly consistent with recombination (SI Fig. 3). Likely due to the relatively short region analyzed, the SiScan method failed to detect recombination in specimen 2010_29297 (participant 5060), although all other methods in RDP4 (p < 8.0 × 10−5) and the phi-statistics (p = 4.1 × 10−7) presented high statistical significance. Each RDP4 method (p < 1.5 × 10−6) and the phi statistics (p = 4.3 × 10−9) were significant for recombination for 2008_35742 (participant 6376). Taken together, the most parsimonious explanation for both the common HG52 group and these rare, short HSV-1 UL39 fragments is an ancestral long recombination event giving rise to G19080, followed by back-recombination events wherein a part of the HSV-1 fragment in G19080 was expelled by recombination with a 186-like HSV-2 strain.

We noted additional unique sequences in the C-terminal UL39 phylogeny (Fig. 1). Sequencing revealed three additional probable additional recombinants, each with HSV-1-like sequences remaining internal to the long G19080 HSV-1 insert (Supplementary Table 3), but with complex patterns. Sample 2009_2198 from an HIV-infected Zambian man and sample G19083 (ref. 14, from an HIV-uninfected US man) each had distinct sequence with four contiguous HSV-1 markers (blue bars in Fig. 2A). The 3′ crossover markers of the HSV-1 insert in 2009_2198 match the HG52 subgroup, suggesting common ancestry and a backcross. Sample 2009_4556 from an HIV co-infected Kenyan man has three regions of contiguous HSV-1 allelic markers. The 5′ end of 5′-most HSV-1 insert and the 3′ end of the 3′-most HSV-1 insert were identical to the HSV-1 flanking markers of G19080, suggesting common ancestry and backcrosses. Overall, we detected 6 distinct backcross patterns of HSV-1 × HSV-2 UL39 recombination within the longest G19080 recombination event (Fig. 2A).

Distribution of UL39 variants

Evidence for geographically restricted HSV-2 genotypes is limited14,20. From 193 persons in this report and published data (Table 1)14,15,16, we excluded 8 published strains with uncertain geographic origin and one HIV co-infected and one HIV non-infected participant with evidence for dual strain infection (below), leaving 183 participants (Table 3). Excluding the 5 rare UL39 genotypes noted above, 178 had mono-infection with a prevalent UL39 variant (51 from North America, 49 from South America, 70 from Africa, and 8 from Asia). Each major UL39 genotype was detected in Africa, North America, and South America in roughly equal proportions (Table 3). Specifically amongst 51 participants from North America with single-strain infection, 31 (61%), 16 (31%) and 4 (8%) had the SD90e, G19080, and HG52 genotypes, respectively. For the 49 participants from South American, the distribution was 31 (63%), 16 (33%), and 2 (4%) respectively for these genotypes, and for the 70 donors from Africa with single-strain infection, the distribution was 45 (57%), 17 (24%), and 8 (11%). Asian participants, limited to 8 from Japan14, each had the SD90e genotype. Amongst these 178 participants with the 3 prevalent UL39 genotypes, there was no association between continent and UL39 genotype (p = 0.30 or p = 0.58 excluding or including Japanese specimens, respectively).

Table 3. Geographic distribution and HIV co-infection status of study participants with single defined HSV-2 UL39 genotypes and known geographic origin.

| UL39 genotype | Continent |

Total N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | South America | Africa | Asia | ||

| HSV-2 SD90e/186-like | 31 | 31 | 45 | 8 | 115 |

| HIV co-infected | 4 | 20 | 29 | 0 | 53 (46%) |

| HIV un-infected | 25 | 11 | 14 | 0 | 50 (44%) |

| HIV infection status unknown | 2 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 12 (10%) |

| G19080 long HSV-1 insert | 16 | 16 | 17 | 0 | 49 |

| HIV co-infected | 6 | 11 | 6 | 0 | 23 (49%) |

| HIV un-infected | 10 | 5 | 10 | 0 | 25 (49%) |

| HIV infection status unknown | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| HG52 short HSV-1 insert | 4 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 14 |

| HIV co-infected | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 6 (43%) |

| HIV un-infected | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 8 (57%) |

| rare UL39 genotypes | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| HIV co-infected | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 (40%) |

| HIV un-infected | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (60%) |

| total | 54 | 49 | 72 | 8 | 183 |

Distribution of recombinant strains in persons of known HIV status

Amongst the 183 persons donating specimens with a single UL39 genotype and with known geographic origin, we examined the distribution of UL39 genotypes and HIV infection status (Table 3). Amongst these persons, 13 had unknown HIV status, leaving 170 participants, and within these, 5 were infected with HSV-2 strains with rare UL39 genotypes, leaving 165 persons (83 HIV-uninfected and 82 HIV co-infected) infected with one of the three prevalent UL39 genotypes. Each major UL39 genotype were detected in both HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected pesons in roughly equal proportions. Amongst the 83 HIV-uninfected persons, 50 (60%), 25 (30%) and 8 (10%) were infected with the SD90e, G19080, and HG52 genotypes, respectively. Among 82 the HIV co-infected persons, 53 (65%), 23 (28%), and 6 (7%) were infected with SD90e, G19080, and HG52 genotypes, respectively. There was no apparent association between HIV infection status and the three prevelant UL39 genotypes (p = 0.51). For UL30 (discussed below), 7 of 72 (9.7%) HIV co-infected and 2 of 66 (3%) HIV-uninfected persons with available data had the variant (p = 0.29). For UL29 (also discussed below), only one person had the rare variant such that HIV co-infection correlates were not meaningful.

Co-infection with HSV-2 UL39 variants

Within-person dual-strain HSV-2 infection is required for HSV-2 × HSV-2 recombination, such as those implied by the data discussed above. A rectal swab from a HIV-infected Peruvian man, R-103-1010 had multiple C-terminal heterozygous UL39 loci detected by NGS, manual sequencing of bulk UL39 PCR product, and clonal analysis of amplicons cloned from PCR product (SI Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 6). The pattern indicated a simultaneous, dual HSV-2 SD90e-group and G19080-group infection pattern. UL39 bulk PCR amplicon sequencing of 10 additional swabs collected over a 14 day genital HSV-2 outbreak were also each heterozygous, indicating a prolonged episode of simultaneous dual-strain infection. Separately, we found that HIV un-infected North America participant 11848 had either a pure SD90e group- or a pure G19080-group UL39 ddPCR pattern in swab DNA samples collected 4 years apart (SI Table 6), consistent with dual strain infection but not simultaneous reactivation.

HSV-2 UL30 and UL29 genes with HSV-1 × HSV-2 recombination

UL30 encodes DNA polymerase with mutations conferring drug resistance21. It is required for viral replication, has a proof-reading exonuclease function, and cooperatives with UL42 processitivity factor. Burrel et al. sequenced a C-terminal UL30 variant, termed HSV-2v, from cultured isolates from HIV co-infected West Africans5. We sequenced UL30 in Ugandan specimen 5073_9333, using target capture to enrich HSV DNA (Greninger et al. in preparation), and obtained sequence essentially identical to HSV-2v (SI Table 6). We found HSV-2v in 9 (6%) of 146 persons using a ddPCR assay data (SI Table 4). These included 6 of 49 Eastern or Southern African, 1 of 46 North American, and 2 of 51 South American subjects. HIV co-infection was present in 7 persons, but absent in one Ugandan, and in the US subject. The American participants with HSV-2v UL30 had the G19080 HSV-1 UL39 insert, while each African had the SD90e group UL39 gene.

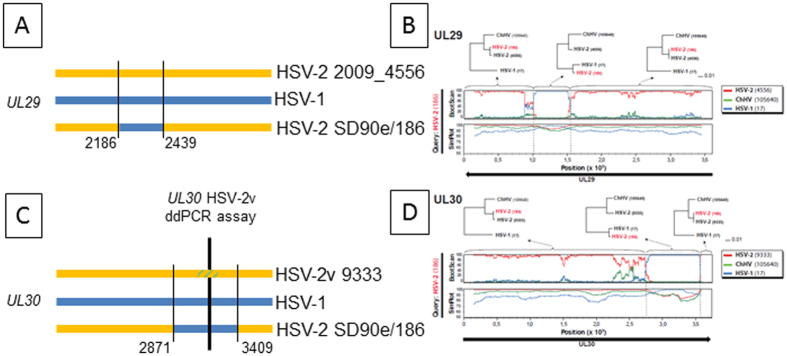

Burrel et al. proposed that HSV-2v UL30 resulted from HSV-2-ChHV recombination5. We aligned full length UL30 from HSV-1 (n = 98), ChHV22, HSV-2v, HSV-2 NGS sequences13,14,15,16, laboratory strains, and HSV-2 sequences in Genbank. HSV-1 UL30 were closely related, with maximum pairwise uncorrected nucleotide distance of 0.01 and little C-terminal variation. HSV-1 17+ and HSV-2 186 were chosen as the species genotypes for recombination analyses for consistency with our analyses of UL39. For both UL30 and UL29, strains 186 and the proposed prototype strain SD90e were extremely similar. We noted that most HSV-2 UL30 sequences have a 539 bp zone of identity to HSV-1 (Table 2, Fig. 4C). This zone contains over 70 consecutive HSV-1-specific allelic SNPs and an HSV-1-specific 12 bp insert. Lateral to this zone, all HSV-2 UL30 genes, including HSV-2v, are similar, and quite dissimilar from HSV-1 (Fig. 4D). Contravening the ChHV hypothesis, many SNPs and a 3 bp indel in the 539 bp region separate HSV-2v from ChHV. Bootscan (Fig. 4D) confirmed a HSV-1 × HSV-2 crossover event with highly shifting bootstrap values supporting different phylogenetic topologies. Simplot analysis further supported recombination by significant shifts in sequence similarity. Phylogenetic analyses of discrete regions of UL30 demarcated by the putative crossover zones associated with the tree clustering patterns (Fig. 4D). The phi-statistics (p = 0.0) and RDP4 algorithms demonstrated high significance for recombination (p < 7.6 × 10−18 for all methods). Most contemporary HSV-2, exemplified by strains SD90e and 186, have an HSV-1 UL30 insert. We hypothesize that UL30 HSV-2v may retain an older sequence related to ChHV.

Figure 4. HSV UL29 and UL30 genotypes in strains circulating in humans.

(A and C) schematic diagrams of C-terminal coding sequences to approximate scale. HSV-1 is blue, rare HSV-2 strains are yellow. Blue bars in HSV-2 SD90e/186 represent circulating HSV-2 strains that have identity to HSV-1 in this region. Thin vertical black lines and associated strain 186 nucleotide numbers mark lateral flanks of HSV-1 identity. For UL30, thick vertical bar and yellow/green hatched zone within HSV-2v 9333 UL30 represent the locus detected by a ddPCR assay for which strain HSV-2v 9333 contains a variant nucleotide. (B,D) Recombination analysis of the UL29 and UL30 genes in HSV-2 strain 186. Bootscan and Simplot analyses are depicted for each gene. Clear shifts in bootstrap values supporting different phylogenetic topologies indicate recombination crossovers in both genes (also indicated by dotted lines). These crossovers are supported by the Simplot analysis, which demonstrates a shift in similarity with a higher similarity to HSV-1 in the recombination fragments. To further test and visualize ancestry of the recombination fragments, phylogenetic trees based on the recombination fragment and flanking regions are shown. HSV-2 strain 186 clearly shifts from clustering closely to HSV-2 in the trees based on the flanking regions, to clustering closely to HSV-1 in the trees based on the recombination fragments. These results suggest recombination with HSV-2 as major parental, and HSV-1 as minor parental strains.

HSV UL29 encodes a DNA binding protein, ICP8, involved in DNA unwinding and origin of replication processes, interacting with multiple viral and host proteins. HSV-1 UL29 sequences (n = 81) were very similar, with a maximum nucleotide distance of 0.0097 and no indels. Alignments of HSV-2 UL29 disclosed one divergent sequence, 2009_4556, from a 30 year old HIV-infected Kenyan (Fig. 4A). Phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 4B) paralleled UL30. Between bp 2186 and bp 2439, HSV-2 186 and SD90e, and other HSV-2 strains show near-identity to HSV-1, including 19 consecutive HSV-1-like alleles. This 254 bp segment placed HSV-1 in the same group as the majority HSV-2 genotype (Fig. 4B). This single unique strain contained 10 differences from ChHV in this region, arguing against origination through recombination with ChHV. Lateral to this region, all HSV-2 were similar but not identical to ChHV and quite divergent from HSV-1. Similar to UL39 and UL30, the bootscan, Simplot, and segmental phylogenetic analyses of UL29 showed distinct shifts in phylogenetic topologies and sequence similarity, consistent with HSV-1 × HSV-2 recombination. Recombination was statistically supported by the phi-statistics (p = 4.4 × 10−10) and the RDP4 program (p < 5.9 × 10−6 for all methods except RDP, which did not detect recombination). We propose that an ancestral HSV-1 × HSV-2 UL29 crossover has become near-fixed in HSV-2, with 2009_4556 as the only currently known strain perhaps retaining an ancestral sequence.

Discussion

We document HSV-2 strains containing regions of HSV-1 sequence identity within three distinct nucleotide metabolism genes, UL29, UL30, and UL39, involved in HSV virulence, replication, and drug activity. The strains likely arose from interspecies recombination. The principle of HSV-1 × HSV-2 recombination in vivo in the natural host has now been established. These findings have implications for viral evolution, HSV drug therapy, vaccines, and viral vector safety.

UL30 is targeted by HSV drugs23 and UL29 and UL39 are also antiviral targets24,25,26,27,28. While UL30 HSV-2v strains are drug-sensitive23, our data suggest that resistance alleles could disseminate via recombination, including across the HSV-1/HSV-2 divide. Attenuated HSV-2 strains29 used as vaccines are also of potential concern. These could recombine with HSV-1 to yield replication-competent variants with unexpected properties. Similarly, a replication competent HSV-1 strain expressing GM-CSF is US-licensed for intratumoral injection as oncolytic therapy, at up to 4 × 108 infectious units. Recurrent HSV-2 replication can occur at widespread anatomic areas, including within the central nervous system to cause recurrent meningitis30. The possibility of recombinants bearing HSV-2 virulence and replication genes and GM-CSF may be possible has been previously discussed31. There is no reason to think that gain of GM-CSF by a wild-type HSV-2 strain would be lead to a selective advantage or increase pathogenicity. Of potentially higher concern, some of the genes deleted in the cancer therapy HSV-1 strain to reduce virulence could be regained, as their HSV-2 versions, via interspecies recombination.

HSV-1 and HSV-2 have separate, overlapping ecologic niches. HSV-1 lytic infection typically involves oral or ocular regions, with latency in trigeminal ganglia. HSV-2 lytic replication is commonest in the anogenital region, with latency in lumbosacral ganglia. Alphaherpesviruses in non-human primates typically show one of these anatomic preferences. The genes responsible for tropism are poorly understood. Remarkably, primary HSV-1 infection now accounts for the majority of cases of clinical first episode genital herpes in the US and northern Europe, while in earlier decades, HSV-2 predominated32,33. An RFLP search for HSV-1 × HSV-2 IRV amongst HSV-1 strains recovered from human recurrent genital infections did not reveal insertions of HSV-2 sequence34. Thus far, analysis of wild-type, low-passage HSV-1 strains by NGS has not revealed insertion of HSV-2 sequences35,36,37, but NGS-based examination of genital HSV-1 strains has not been performed.

HSV-1 × HSV-2 IRV can occur after cell co-infection in vitro. Complex patterns of multiple crossovers are typically observed within progency strains. There is some sequence preference for inclusion of origins of replication3,38 in crossed-over segments. Both these spontaneous IRV, and engineered IRV that are crossed over at desired loci, have been widely used to map species-specific phenotypes (for example39,40). The large number of such studies cannot be reviewed in detail. Regarding anatomic tropism, in vivo research using engineered HSV-1 × HSV-2 IRV suggests segregation of tropism with DNA encoding latency-associated transcripts41. Thus far, we have not detected naturally occurring IRV in these loci. Studies in vivo suggest that IRV generally have attenuated virulence42,43. In contrast the IRV described in this report by definition are virulent for infection of humans. IRV can occur in vivo after experimental simultaneous HSV-1 and HSV-2 co-inoculation of animals44. All animal models have a fundamental differences in pathogenesis compared to HSV infection of humans, for example acute lethality in some systems, and lack of recurrences in almost all. Given the exquisite host-pathogen co-evolution of HSV with humans, demonstration the HSV-1 × HSV-2 IRV occur in the natural host establish a new mechanism for HSV evolution.

We hypothesize that all variants of HSV-2, as well as ChHV, are descended from a common ancestor of HSV-2/ChHV, estimated to have infected a primate around 2 million years ago, rather than by HSV-2/ChHV recombination5. A recent estimate places human/chimp divergence at 13 million years ago45. We cannot date the HSV-2 × HSV-1 recombination events, but based on the relatively equal geographic distribution of the major UL39 variants, each appears to predate human emigration from Africa (now estimated at about 70,000 years ago46). Recent horizontal transmission of UL39 variants is also possible. Resolution will require larger, curated specimen sets including those from isolated populations, and optimally archival DNA from before the era of widespread travel. In preliminary analyses of phylogenetic networks, we studied the HSV-1 UL39 insert found in HSV-2 strain G19080 and the corresponding region from known HSV-1 strains. No clustering into clades was observed as seen for HSV-1 US7 or US8. Interestingly, the HSV-2 strain 19080 UL39 HSV-1 fragment does not cluster more distantly or closely to any particular HSV-1 strain than do HSV-1 strains cluster with each other. This implies that the HSV-1 UL39 fragment in HSV-2 G19080 was incorporated into this strain through homologous recombination after emergence of the most recent common ancestor of circulating HSV-1 strains, estimated to have occurred 700,000 years ago4.

After their origination, IRV have had different fates in the population. Within UL29 and UL30, small minorities of strains lack the HSV-1-like regions, likely related to fitness. For UL39, in contrast, the relatively equal prevalence of the three major genotypes implies that none has a large fitness advantage. It is also possible, especially for UL29 and UL30, that a bottleneck occurred during migration from Africa, as the rare variants are thus far found mostly in Africa.

The grouping of IRV signatures in the 3′ region of HSV UL39, including evidence for multiple back-crosses, suggests an ancestral recombination leading to the G19080 group, and susceptibility to back-recombination in this area. It is possible that the recombination points that flank the HSV-1 insert within the HSV-2 G19080 group arose multiple times due to strong site preferences for recombination. Sequence bias for HSV IRV formation has been noted in vitro3, but the mechanism is unknown. In this earlier work, crossovers were noted near UL39 but not mapped precisely. The HSV origin of replication in the HSV unique long (UL) region is between UL29 and UL30, but it is not known if this is related to IRV formation. A correlation was found between high GC content and intratypic recombination for HSV-147. HSV-1 UL29, UL30, and UL39 GC content very near the average of 66.8% for HSV-1 UL, disfavoring GC content as an explanation. Overall, we consider multiple, independent crossover events less likely than persistence of a relatively ancient recombinant G19080 UL39 variant in the human population as well as the persistence of the progeny of occasional back-crosses to HSV-2.

Strengths of our approach include the use of direct sequencing, international specimens, the availability of multiple specimens from some subjects to document multi-strain infection, and sequence confirmation with several technologies. HSV sequences can shift in vitro48 with mutation rates 10–100 fold higher for HSV-2 than HSV-1, and may favor certain genes49. UL39 appears stable in vitro: our lab′s strain 333 is identical to that from 3 other labs. The complementary genotyping platforms each have strengths and weaknesses. In-lab progress in HSV-2 target enrichment has recently made direct NGS sequencing practical and economical for swab specimens with scarce HSV-2 DNA and will likely be used in the future.

Our study has several caveats. We may have missed additional IRV within UL39, as ddPCR rather than sequencing was used for some specimens. For example, specimen 2008_35742 and specimen 2010_29297 had the same ddPCR patterns (Fig. 2A), but sequencing revealed different 5′ recombination zones. We used a relatively limited set of HSV-2 sequences to detect IRV. Additional full-length HSV-2 sequences including specimens from other continents will likely identify other sites of recombination. Of special interest are detailed studies of specimens from persons with both HSV-1 and HSV-2 infections at the same anatomic site, which might reveal additional and possibly transitory IRV. Our cross-sectional specimen set likely failed to detect some interspecies recombination events that have occurred in the past due to decay of IRV with a fitness disadvantage, and similarly, the temporal sequence of events leading to the variants circulating today cannot be assigned with certainty. Long term, IRV with fitness advantages could reach 100% prevalence, appear as tracts of HSV-1/HSV-2 identity, and again be undetectable without longitudinal samples. The effects of the recombination events detected in this study can be tested in vitro or in animals, but it will be difficult to prove their effects on virulence in the natural host.

It has recently been suggested that HSV-2 strain SD90e be used as a prototype, as it is more virulent in animals, is lower passage, and has a functional copy of a gene disabled in HG5215. As discussed herein, we elected to use strain 186 as the representative of the most abundant UL39 genotype for our formal recombination analyses, as strain SD90e contains a rare 9 basepair deletion in UL39. Otherwise, the sequences of 186 and SD90e are very similar for the three genes in which we detected interspecies recombination and overall, our data partially support SD90e as an HSV-2 prototype. The selection of a HSV-2 strain as genotypic prototype is complex. Strains 333 and SD90e are identical in the C terminal region of UL39, but the 9 basepair deletion seen in SD90e is not present in 333. We propose that SD90e is a better rational candidate for prototype strain given the fact that 333 is highly passaged and has not been compared head to head with other strains for virulence or protection after administration of candidate vaccines, as has SD90e18. For HSV-1, the use of HSV-1 17+ for analyses of UL29, UL30, and UL39 is reasonable as there is no consensus as to prototype strain. For the three HSV genes in this report, strain 17+ is closely representative of every HSV-1 sequence data available in Genbank, including those recently analyzed by Szpara et al.35,36,50 and of any other HSV-1 strain would have no bearing on the conclusions of this study. This area will likely undergo further refinement as additional sequences and analyses become available.

Functional studies with variant UL29, UL30, and UL39 proteins and virus genotypes will be necessary to examine the biological consequences of variation. These genes are pivotal in HSV pathogenesis. Briefly, UL39 is non-essential in vitro but required for virulence in vivo, while UL29 and UL30 are essential regardless. UL39 variants could influence dNTP pools and neuronal reactivation, as UL39 is required for replication in neurons with low endogenous dNTP levels. Additional UL39 functions include an N-terminal RHIM domain that inhibits necroptosis51, a possible protein kinase52, and a C-terminal region has been implicated in inhibition of apoptosis. The UL29 ssDNA binding protein is involved in DNA unwinding and origin of replication processes, interacting with multiple cellular and viral proteins. The UL30 DNA polymerase has a proofreading exonunclease function and cooperates with the UL42 processivity factor; mutations can lead to mutator phenotypes and altered drug sensitivity. The variant proteins uncovered herein can be studied biochemically, in vitro, or in vivo in the isogenic virus context. Within the immunocompetent population there is enormous person-to-person variation in the frequency of HSV-2 symptomatic recurrence and asymptomatic shedding53. Quantitative study of reactivation parameters in persons with prevalent IRV genotypes might reveal phenotypic-genotpye correlations.

In summary, contemporary circulating genital HSV-2 strains recovered from widely distributed geographic areas show evidence for recombination with HSV-1. The pattern of UL39 sequence variants, taken together, is consistent with an ancestral crossover event followed by backcrosses to HSV-2. Data for UL29 and UL30 are most consistent with an ancient HSV-1 crossover that has been successfully propagated in the human population, leaving a minority of residual strains with sequences similar to ChHV, the closest known relative of HSV-2. Overall, the principle of HSV-1 × HSV-2 interspecies recombination in vivo has now been established in the natural host.

Methods

Subjects and specimens

Protocols were approved by the Univerity of Washington Institutional Review Board and all participants provided informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations for human subjects research. Sources included natural history and interventional protocols HPTN 039 and Partners in Prevention, concerning HSV-2 and HIV transmission54,55, natural history studies, and a drug treatment study56. Subjects and specimen details for NGS have been documented57.

Sequence determination, confirmation, and genotyping

The next-generation sequencing (NGS) laboratory and analysis workflow has been reported57 and data uploaded (Genbank accessions KX574861-KX574908 inclusive). BAM Illumina sequence files were assembled and visualized with NCBI Genome Workbench and Integrative Genomics Viewer58. Supporting Information Methods contains primers for PCR amplification and dideoxy sequencing of selected regions of HSV-2 DNA (SI Table 5), rapid genotyping by ddPCR (SI Table 4), and Genbank accession numbers (SI Table 6) of new sequences.

Nucleotide alignment and recombination detection

We accessed full-length ChHV, HSV1 and HSV-2 UL39 sequences from recent NGS data and other Genbank-available sequences including BLAST searches using HSV-2 HG52 or HSV-1 strain 17 full length U39 sequences as search terms. Only full-length sequences without ambiguous base calls were used. UL39 sequences were analyzed full-length or starting at base 1,000 in HSV-2 strain 186 coordinates. Alignments were performed with MegAlign Pro (Lasergene, Madison, WI) using MUSCLE and default parameters. Genetic distances were calculated by the Tamura-Nei method59 using Megalign Pro. Phylogenetic trees were generated in MegAlign Pro using default parameters and visualized with Figtree 1.4.2 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). Re-rooting for visualization was done within Figtree. Recombination crossovers were identified and visualized using the bootscan method included in the Simplot program. Sequence similarities between different strains were analyzed and visualized using Simplot. The parameter settings for bootscan and Simplot were as follows: Window size: 300 bp, step: 5 bp, gapstrip: on, Kimura (2-parameter), and T/t = 2.0. Detection of recombination, and calculation of statistical significance for recombination, was further performed using the RDP, GENECONV, bootScan, MaxChi, Chimaera, and SiScan algorithms implemented in the RDP4 program19 using default settings, and the phi-statistics implemented in the SplitsTree program, after discarding all but one of each set of identical sequences. Phylogenetic trees (networks) based on recombinant fragments, and flanking regions, were constructed using the SplitsTree program and the uncorrected P characters transformation and default settings. Similar analyses were performed for UL30 and UL29.

Statistics

The abundance of UL39 genotypes in different continents or among persons with different HIV status was compared with Fisher’s exact test or Chi-squared test, two-tailed.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Koelle, D. M. et al. Worldwide circulation of HSV-2 × HSV-1 recombinant strains. Sci. Rep. 7, 44084; doi: 10.1038/srep44084 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funded by NIH R21AI096058, P01AI031731, R01AI094019, U01 AI52054, U01 AI46749, and CFAR AI027757, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation 26469, HPTN039 supported through NIH U01 AI52054 and HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) under U01 AI46749, sponsored by NIH NIAID, NICHD, NIDA, NIMH, and Office of AIDS Research. We thank Beatrice Hahn (University of Pennsylvania) and Paul Sharp (University of Edinburgh) for insightful discussions.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Conception of study D.M.K., A.W. and C.J. Performing experiments A.L.G., R.M.R., M.L.H., L.S., L.J., K.D. and H.X. Analaysis of data D.M.K., P.N., M.P.F., A.S.M. and A.L.G. Management of data S.S. Recruitment of subjects C.C., J.R.L., A.W. and C.J. Writing paper D.M.K., P.N., A.W., K.R.J. and C.J.

References

- Wertheim J. O., Smith M. D., Smith D. M., Scheffler K. & Kosakovsky Pond S. L. Evolutionary origins of human herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. Molecular biology and evolution 31, 2356–2364, doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu185 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertke A. S., Patel A. & Krause P. R. Herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript sequence downstream of the promoter influences type-specific reactivation and viral neurotropism. Journal of virology 81, 6605–6613, doi: 10.1128/JVI.02701-06 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse L. S., Buchman T. G., Roizman B. & Schaffer P. A. Anatomy of herpes simplex virus DNA. IX. Apparent exclusion of some parental DNA arrangements in the generation of intertypic (HSV-1 × HSV-2) recombinants. Journal of virology 24, 231–248 (1977). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norberg P. et al. A genome-wide comparative evolutionary analysis of herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella zoster virus. PLoS One 6, e22527, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022527 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrel S. et al. Genetic Diversity within Alphaherpesviruses: Characterization of a Novel Variant of Herpes Simplex Virus 2. Journal of virology 89, 12273–12283, doi: 10.1128/JVI.01959-15 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagamjav O., Sakata T., Matsumura T., Yamaguchi T. & Fukushi H. Natural recombinant between equine herpesviruses 1 and 4 in the ICP4 gene. Microbiology and immunology 49, 167–179 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley K. A. The double-edged sword: How evolution can make or break a live-attenuated virus vaccine. Evolution 4, 635–643, doi: 10.1007/s12052-011-0365-y (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norberg P. et al. Recombination of Globally Circulating Varicella-Zoster Virus. Journal of virology 89, 7133–7146, doi: 10.1128/JVI.00437-15 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. W. et al. Attenuated vaccines can recombine to form virulent field viruses. Science 337, 188, doi: 10.1126/science.1217134 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa X. J., Morrison L. A. & Knipe D. M. Comparison of different forms of herpes simplex replication-defective mutant viruses as vaccines in a mouse model of HSV-2 genital infection. Virology 288, 256–263, doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1094 S0042-6822(01)91094-3 [pii] (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markert J. M. et al. A phase 1 trial of oncolytic HSV-1, G207, given in combination with radiation for recurrent GBM demonstrates safety and radiographic responses. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 22, 1048–1055, doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.22 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley H., Markowitz L. E., Gibson T. & McQuillan G. M. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2–United States, 1999-2010. The Journal of infectious diseases 209, 325–333, doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit458 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C., Magaret A., Sather C., Diem K., Huang M., Selke S., Lingappa J. R., Celum C., Koelle D. M. & Wald A. In World STI and HIV Congress 2015. Abstract A46.

- Newman R. M. et al. Genome Sequencing and Analysis of Geographically Diverse Clinical Isolates of Herpes Simplex Virus 2. Journal of virology 89, 8219–8232, doi: 10.1128/JVI.01303-15 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgrove R. et al. Genomic sequences of a low passage herpes simplex virus 2 clinical isolate and its plaque-purified derivative strain. Virology 450–451, 140–145, doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.12.014 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb A. W., Larsen I. V., Cuellar J. A. & Brandt C. R. Genomic, phylogenetic, and recombinational characterization of herpes simplex virus 2 strains. Journal of virology 89, 6427–6434, doi: 10.1128/JVI.00416-15 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeoch D. J. et al. The complete DNA sequence of the long unique region of herpes simplex virus type 1. Journal of General Virology 69, 1531–1574 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek T. E., Torres-Lopez E., Crumpacker C. & Knipe D. M. Evidence for differences in immunologic and pathogenesis properties of herpes simplex virus 2 strains from the United States and South Africa. The Journal of infectious diseases 203, 1434–1441, doi: jir047 [pii] 10.1093/infdis/jir047 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. P., Murrell D., Golden M., Khoosal A. & Muhire B. RDP4: Detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evolution 2015, 1–5 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norberg P., Kasubi M. J., Haarr L., Bergstrom T. & Liljeqvist J. A. Divergence and recombination of clinical herpes simplex virus type 2 isolates. Journal of virology 81, 13158–13167, doi: JVI.01310-07 [pii] 10.1128/JVI.01310-07 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn K., Zell R., Schacke M., Wutzler P. & Sauerbrei A. Gene polymorphism of thymidine kinase and DNA polymerase in clinical strains of herpes simplex virus. Antiviral therapy 16, 989–997, doi: 10.3851/IMP1852 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severini A., Tyler S. D., Peters G. A., Black D. & Eberle R. Genome sequence of a chimpanzee herpesvirus and its relation to other primate alphaherpesviruses. Archives of virology 158, 1825–1828, doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1666-y (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrel S. et al. Detection of a new variant of herpes simplex virus type 2 among HIV-1-infected individuals. Journal of clinical virology: the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology 57, 267–269, doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.03.008 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergerie Y. & Boivin G. Hydroxyurea enhances the activity of acyclovir and cidofovir against herpes simplex virus type 1 resistant strains harboring mutations in the thymidine kinase and/or the DNA polymerase genes. Antiviral research 77, 77–80, doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.08.009 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanovskaya A. et al. Enzymatically produced pools of canonical and Dicer-substrate siRNA molecules display comparable gene silencing and antiviral activities against herpes simplex virus. PLoS One 7, e51019, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051019 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palliser D. et al. An siRNA-based microbicide protects mice from lethal herpes simplex virus 2 infection. Nature 439, 89–94, doi: 10.1038/nature04263 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. et al. Durable protection from Herpes Simplex Virus-2 transmission following intravaginal application of siRNAs targeting both a viral and host gene. Cell host & microbe 5, 84–94, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.12.003 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paavilainen H. et al. Inhibition of clinical pathogenic herpes simplex virus 1 strains with enzymatically created siRNA pools. Journal of medical virology, doi: 10.1002/jmv.24578 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek T., Mathews L. C. & Knipe D. M. Disruption of the U(L)41 gene in the herpes simplex virus 2 dl5-29 mutant increases its immunogenicity and protective capacity in a murine model of genital herpes. Virology 372, 165–175, doi: S0042-6822(07)00669-1 [pii] 10.1016/j.virol.2007.10.014 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalabi M. & Whitley R. J. Recurrent benign lymphocytic meningitis. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 43, 1194–1197, doi: 10.1086/508281 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs P. R., Verhagen J. H., van Eijck C. H. & van den Hoogen B. G. Oncolytic viruses: From bench to bedside with a focus on safety. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 11, 1573–1584, doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1037058 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein D. I. et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 56, 344–351, doi: 10.1093/cid/cis891 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuis R. F., van Doornum G. J., Mulder P. G., Neumann H. A. & van der Meijden W. I. Importance of herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) in primary genital herpes. Acta dermato-venereologica 86, 129–134, doi: 10.2340/00015555-0029 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fife K. H. & Boggs D. Lack of evidence for intertypic recombinants in the pathogenesis of recurrent genital infections with herpes simplex virus type 1. Sexually transmitted diseases 13, 138–144 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szpara M. L., Parsons L. & Enquist L. W. Sequence variability in clinical and laboratory isolates of herpes simplex virus 1 reveals new mutations. Journal of virology 84, 5303–5313, doi: JVI.00312-10 [pii] 10.1128/JVI.00312-10 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szpara M. L. et al. Evolution and diversity in human herpes simplex virus genomes. Journal of virology 88, 1209–1227, doi: 10.1128/JVI.01987-13 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff F., Groth M., Sauerbrei A. & Zell R. Genotyping of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) by whole genome sequencing. The Journal of general virology, doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000589 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra S. K. & Brown S. M. Analysis of unselected HSV-1 McKrae/HSV-2 HG 52 recombinants demonstrates preferential recombination between intact genomes and restriction endonuclease fragments containing an origin of replication. Archives of virology 105, 1–13 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliburton I. W., Morse L. S., Roizman B. & Quinn K. E. Mapping of the thymidine kinase genes of type 1 and type 2 herpes simplex viruses using intertypic recombinants. The Journal of general virology 49, 235–253 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelle D. M. et al. Antigenic specificity of human CD4+ T cell clones recovered from recurrent genital HSV-2 lesions. Journal of virology 68, 2803–2810 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa T. et al. The characteristic site-specific reactivation phenotypes of HSV-1 and HSV-2 depend upon the latency-associated transcript region. The Journal of experimental medicine 184, 659–664 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. L. & Stevens J. G. Biological characterization of a herpes simplex virus intertypic recombinant which is completely and specifically non-neurovirulent. Virology 131, 171–179 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javier R. T., Thompson R. L. & Stevens J. G. Genetic and biological analyses of a herpes simplex virus intertypic recombinant reduced specifically for neurovirulence. Journal of virology 61, 1978–1984 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yirrell D. L., Rogers C. E., Blyth W. A. & Hill T. J. Experimental in vivo generation of intertypic recombinant strains of HSV in the mouse. Archives of virology 125, 227–238 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venn O. et al. Nonhuman genetics. Strong male bias drives germline mutation in chimpanzees. Science 344, 1272–1275, doi: 10.1126/science.344.6189.1272 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer S. Out-of-Africa, the peopling of continents and islands: tracing uniparental gene trees across the map. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 367, 770–784, doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0306 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. et al. Recombination Analysis of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Reveals a Bias toward GC Content and the Inverted Repeat Regions. Journal of virology 89, 7214–7223, doi: 10.1128/JVI.00880-15 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maertzdorf J., Remeijer L., Van Der Lelij A., Buitenwerf J., Niesters H. G. M., Osterhaus, A. D. M. E. & Verjans G. M. G. M. Amplification of reiterated sequences of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) genome to discriminate between clinical HSV-1 isolates. Journal of clinical microbiology 37, 3518–3523 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarisky R. T., Nguyen T. T., Duffy K. E., Wittrock R. J. & Leary J. J. Difference in incidence of spontaneous mutations between herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 44, 1524–1529 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szpara M. L. et al. A wide extent of inter-strain diversity in virulent and vaccine strains of alphaherpesviruses. PLoS pathogens 7, e1002282, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002282 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H. et al. Herpes simplex virus suppresses necroptosis in human cells. Cell host & microbe 17, 243–251, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.01.003 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins D., Pereira E. F., Gober M., Yarowsky P. J. & Aurelian L. The herpes simplex virus type 2 R1 protein kinase (ICP10 PK) blocks apoptosis in hippocampal neurons, involving activation of the MEK/MAPK survival pathway. Journal of virology 76, 1435–1449 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronstein E. et al. Genital shedding of herpes simplex virus among symptomatic and asymptomatic persons with HSV-2 infection. JAMA 305, 1441–1449, doi: 305/14/1441 [pii] 10.1001/jama.2011.420 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celum C. et al. Effect of aciclovir on HIV-1 acquisition in herpes simplex virus 2 seropositive women and men who have sex with men: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 371, 2109–2119, doi: S0140-6736(08)60920-4 [pii] 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60920-4 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingappa J. R. et al. Daily aciclovir for HIV-1 disease progression in people dually infected with HIV-1 and herpes simplex virus type 2: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 375, 824–833, doi: S0140-6736(09)62038-9 [pii]10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62038-9 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald A. et al. Helicase-primase inhibitor pritelivir for HSV-2 infection. The New England journal of medicine 370, 201–210, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301150 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C., Magaret A., Cheng A., Diem K., Fitzgibbon M., Huang M.-L., Selke S., Lingappa J. R., Celum C., Jerome K. R., Koelle D. M. & Wald A. Next generation genomic sequencing of herpes simplex virus type 2 using genital DNA swabs. VirologySubmitted (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Thorvaldsdottir H., Robinson J. T. & Mesirov J. P. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Briefings in bioinformatics 14, 178–192, doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K. & Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Molecular biology and evolution 10, 512–526 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.