Abstract

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a complication and marker of disease severity in many parenchymal lung diseases. It also is a frequent complication of portal hypertension and negatively impacts survival with liver transplant. Pulmonary hypertension is frequently diagnosed in patients with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis, and it has recently been demonstrated to adversely affect posttransplant outcome in this patient population even though the mechanism of PH is substantially different from that associated with liver disease. The presence of PH in patients with heart failure is frequent, and the necessity for PH therapy prior to heart transplant has evolved in the last decade. We review the frequency of and risk factors for PH in recipients of and candidates for lung, liver, heart, and renal transplants as well as the impact of this diagnosis on posttransplant outcomes.

Keywords: pulmonary hypertension, parenchymal lung disease, end-stage renal disease, COPD

Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a hemodynamic condition defined by a mean pulmonary artery pressure of > 25 mm Hg at rest as measured by right heart catheterization. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is PH with a normal pulmonary capillary wedge pressure or left ventricular end diastolic pressure without structural cardiac, pulmonary parenchymal, pulmonary vascular, or thrombotic disease.1 PH contributes to patient symptoms, is a marker of disease severity, and increases morbidity and mortality in many of the diseases it complicates. Additionally, PH has the capacity to affect pre- and posttransplant survival in patients requiring solid organ transplantation. Prior reviews have addressed the frequency of lung transplantation as a treatment for PAH and the adverse impact of the Lung Allocation Score on lung transplant access for these patients and on posttransplant outcomes in those who do undergo lung transplantation.2,3 This review will concentrate on those patients with other lung diseases and other end-stage organ diseases that can be complicated by PH.

Lung Diseases Complicated by Pulmonary Hypertension

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

One of the most common causes of death in the United States is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). According to the American Lung Association, COPD is the third-leading cause of U.S. deaths,4 and patients with COPD represent about one-third of all lung transplant recipients.5 A meta-analysis of 10 papers reviewing COPD and hemodynamically confirmed PH concluded that very high pulmonary artery (PA) pressures were relatively rare, that exercise provoked substantial increases in PA pressure, and that survival was inversely proportional to pulmonary vascular resistance.6 The authors emphasized the importance of treatment that focused on the underlying disease state—for example, treating COPD with bronchodilators and oxygen therapy. A review of 4,305 COPD lung transplant candidates from May 2005 compared those with PH (defined as either PA mean > 25 or > 35) to propensity score-matched candidates without PH. Using either definition of PH, there was a significant decrease in survival probability that was both clinically and statistically significant (HR of 3.4 for mortality with PH ≥ 35 [95% CI 2.410, 4.888] P < .001).7 In another cohort of COPD patients who survived to lung transplant, the presence of pretransplant PH was defined by an increase in transpulmonary gradient (TPG), which is the difference between PA mean and wedge pressure (with normal being < 12). COPD patients so characterized as having PH had a 1.74-times higher risk of 1-year posttransplant mortality (P = .001), and this relationship increased at higher levels of TPG. In these COPD patients, a TPG greater than 28 mm Hg conferred a 2-fold increase in relative risk for death compared to COPD patients without PH.8 Interestingly, this impact of PH on posttransplant mortality described in this study was not observed in patients with cystic fibrosis or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

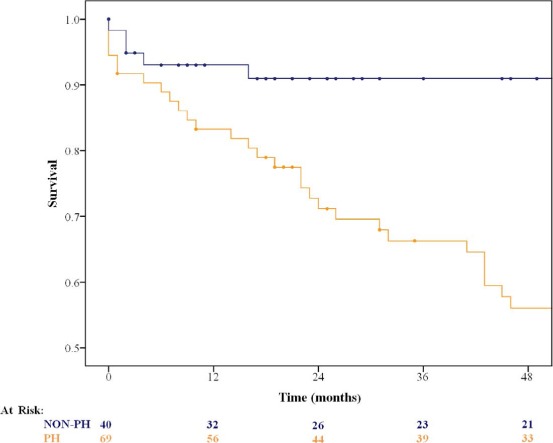

The incidence of PH in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is variably described from 8% to 86% depending on the method used to assess PH (echocardiography or heart catheterization) and the timing of the hemodynamic assessment relative to the time of the transplant and disease duration (Figure 1).9,10 An interventional study that attempted to evaluate the noninvasive predictors of hemodynamically proven PH demonstrated that the presence of PH is best predicted by parameters derived from formal exercise testing (VE vs VCO2 slope and peak VO2). What was most important, however, was that the authors demonstrated that pre-transplant survival was severely impaired in IPF patients with PH.

Figure 1.

Survival of 133 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with and without interceding pulmonary hypertension. Reprinted from Gläser et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis – the predictive value of exercise capacity and gas exchange efficiency. PLoS ONE. 2013 Jun 20;8(6):e65643.

In contrast to what was seen in patients with COPD, the presence of PH in patients with a diagnosis of IPF does not appear to confer a survival risk after transplant.8,11 The issue, then, with patients with IPF and PH is whether or not there is a place for pretransplant treatment with PAH disease-modifying medications. Multiple studies done with endothelin receptor antagonists (macitentan, bosentan, and ambrisentan) have been uniformly negative, and in some cases the data have suggested the potential for irreversible disease worsening.

Similar studies done with phosphodiesterase inhibitors have shown modest improvements in hemodynamics but worsening brain natriuretic peptide levels (suggesting ventricular overload) as well as worsening 6-minute walk test (6MWT) results.12 A 12-week study in 180 IPF patients randomized to placebo or sildenafil failed to meet the primary end point of improvement in effort tolerance as measured by the 6MWT; however, there were some encouraging though nonsignificant trends toward improvement in other physiological measures and symptom scores.13

Liver Disease and Pulmonary Hypertension

Pulmonary hypertension is variably reported to occur in 2% to 10%1 of cirrhotic patients and in as many as 16% of patients with advanced liver disease considered for liver transplantation.14,15 The histological appearance of the plexiform lesions seen in patients with severe portopulmonary hypertension are indistinguishable on H&E staining from classical PAH.16 A review of patients undergoing liver transplantation in the face of varying degrees of PH demonstrated 100% mortality in those with a mean PA pressure > 50 mm Hg and 50% mortality in those with a mean PA pressure between 35 and 49.17 In addition, data from the REVEAL registry have demonstrated that patients with newly diagnosed portopulmonary hypertension have a significantly worse survival (57% ± 8% at 24 months) compared to individuals with idiopathic PAH whether newly or previously diagnosed (82% ± 2% vs 86% ± 1%, respectively).18

In patients undergoing liver transplantation with a prior diagnosis of portopulmonary hypertension, and having received standardized Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) exception points for this diagnosis and its treatment, there is an increased risk of both death and graft failure (HR 2.25 and 1.96, respectively) in the first year after liver transplant compared to those without portopulmonary hypertension.19 This substantial risk may be due to lack of adherence to the carefully defined requirements for resolution and adequacy of hemodynamics prior to transplantation.20 Hence, the presence of PH in those with liver disease confers an increased risk of mortality with or without transplant.

It is important to recognize that liver transplant recipients are probably the sickest patients to undergo organ transplant. Though PH confers additional risk, this should be considered in the context of a 23.4% mortality rate in liver failure patients within the ICU at time of transplant, and a 1.54-fold risk of death within 3 months of transplant in patients with a MELD score of > 35 compared to those with a MELD score between 30 and 34 at transplant.

Pulmonary Hypertension in End-Stage Renal Disease

In the first prospective study of PH in U.S. patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), all patients at a single center underwent echocardiograms prospectively.21 Of the 90 total patients, 47% met echocardiographic criteria for PH (tricuspid regurgitant jet > 2.5 m/s) and 20% had severe PH (tricuspid regurgitant jet > 3.0 m/s); mortality in those with echocardiographic evidence of severe PH was 26% compared to 6% in those without PH. Echocardiographic findings were consistent with left ventricular and fluid overload as the cause of PH.21

Consistent with the premise that left heart disease is a major risk factor for PH in this patient population is the observation that systemic hypertension is more frequent in ESRD patients with PH than in those without PH (33% vs 15%).22 Additionally, PH also impacted transplant outcomes in ESRD patients. Among patients receiving a living donor kidney, early graft dysfunction was not observed regardless of PH status. However, in patients receiving a deceased donor kidney, those with PH had a significant increased risk of early graft dysfunction versus those without PH (56% vs 11.7%, P = .01).22 Univariate and multivariable logistic regression supported this observation as an independent risk factor beyond potentially confounding recipient, donor, and graft-based risk factors for early graft dysfunction (P < .05).23

An extensive review of survival following renal transplant defined pretransplant PH by the echocardiographic estimate of right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP).23 Out of 215 patients, 68% had normal RVSP (< 35 mm Hg), 22% had mild to moderately elevated RVSP (36–50 mm Hg), and 10% had markedly elevated RVSP (> 50 mm Hg) suggestive of severe PH. Time on dialysis was the strongest correlate of an elevated RVSP (r = .253, P < .001).23 An RVSP greater than 50 was associated with significantly reduced posttransplant survival (HR = 3.75, 1.17–11.97; P = .016). This relationship was independent of other variables including older age, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, low serum albumin, and delayed graft function.

Given that the data regarding time on dialysis is found to be predictive of pretransplant PH, and given the association of systemic hypertension and PH in the ESRD patient population, it is reasonable to predict that PH can also arise de novo following a renal transplant. Numerous studies suggest that PH occurs post-transplant in 5% to 14% of patients. A review of the frequency of de novo PH after renal transplant demonstrated that it occurred in 8 of 100 renal transplants and was associated with higher renal resistive index, higher C-reactive protein, and higher pulse wave velocity—all features of chronic injury and vascular stiffness.24 The features of right ventricular dysfunction and PH in patients with ESRD being considered for renal transplantation are highly predictive for both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality following transplantation.25

Pulmonary Hypertension in Left Heart Disease

Pulmonary hypertension is a frequent complication of chronic left heart disease/failure. Irrespective of the cause—be it left ventricular systolic dysfunction, diastolic dysfunction, or valvular abnormalities—pulmonary artery pressure will be disproportionately elevated in about one-third of cases. This may be a genetically determined response to chronic pressure or flow changes in the pulmonary vascular bed that results in a histological appearance similar to that seen in idiopathic PH. Despite the similarities to idiopathic PH, currently available drug therapies for PAH have been universally unsuccessful in mitigating PH due to left-sided heart disease.

Attempts to perform transplants on heart failure patients with PH were associated with increased mortality.26 Patients with a PA systolic pressure > 50 mm Hg associated with an elevated transpulmonary gradient (TPG > 16 mm Hg) suffered a 50% operative mortality rate with cardiac transplant. The higher the PA systolic pressure and the TPG or pulmonary regurgitant velocity, the greater the perioperative mortality. The presence of a pretransplant vasodilator response did not impact mortality.26 Consequently, the current standard of practice is to use a left ventricular assist device (LVAD), biventricular assist device, or total artificial heart to bridge a patient to transplant. Biventricular assist devices probably represent about 20% to 50% of VAD recipients waiting for transplant. Based on this, current studies are looking at PAH-specific therapy to facilitate normalization of regurgitant velocity by acting on the pulmonary vascular bed in these VAD recipients.

Conclusions

Pulmonary hypertension is a frequent complication of both pulmonary and nonpulmonary organ failure. When present, it is a marker of disease severity and associated with higher mortality. It also complicates or prevents solid organ transplant by conferring either immediate perioperative mortality (as is the case in liver and heart transplant) or an increased risk of early graft dysfunction and long-term mortality (as in kidney failure). Though specific therapies for PAH are useful in liver disease, they have not proven useful in heart, kidney, or lung disease where such therapies can in fact be deleterious.

Key Points

Pulmonary hypertension is a frequent complication of both pulmonary and nonpulmonary organ failure and is a marker of disease severity.

PH contributes to patient symptoms and increases morbidity and mortality in many of the diseases it complicates, such as end-stage renal disease, liver disease, and heart failure.

PH can affect pre- and posttransplant survival in patients requiring solid organ transplantation.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

Dr. Frost is a consultant for Gilead Sciences, Inc. and Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc. and conducts research on behalf of Gilead, Actelion, United Therapeutics, Lung Rx LLC, InterMune, and Genentech Inc. In addition, her husband has a financial interest in Gilead.

References

- 1. Hoeper MM, Bogaard HJ, Condliffe R, . et al. Definitions and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013. December 24; 62( 25 Suppl): D42– 50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gomberg-Maitland M, Glassner-Kolmin C, Watson S, . et al. Survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients awaiting lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013. Dec. 32( 12): 1179– 86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benza RL, Miller DP, Frost A, Barst RJ, Krichman AM, McGoon MD.. Analysis of the lung allocation score estimation of risk of death in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension using data from the REVEAL Registry. Transplantation. 2010. August 15; 90( 3): 298– 305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American Lung Association [Internet]. Chicago: American Lung Association; c2016. Lung Health & Diseases: How serious is COPD; 2013 [cited 2016 Jul 19]. Available from: http://www.lung.org/lung-health-and-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/copd/learn-about-copd/how-serious-is-copd.html?referrer=https://www.google.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yusen RD, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, . et al.; International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-first adult lung and heart-lung transplant report–2014; focus theme: retransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014. October; 33( 10): 1009– 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Minai OA, Chaouat A, Adnot S.. Pulmonary hypertension in COPD: epidemiology, significance and management, pulmonary vascular disease: the global perspective. Chest. 2010. June; 137( 6 Suppl): 39S– 51S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hayes D Jr, Black SM, Tobias JD, Mansour HM, Whitson BA.. Prevalence of pulmonary hypertension and its influence on survival in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prior to lung transplantation. COPD. 2016; 13( 1): 50– 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Singh VK, George MP, Gries CJ.. Pulmonary hypertension is associated with increased post-lung transplant mortality risk in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015. March; 34( 3): 424– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hamada K, Nagai S, Tanaka S, . et al. Significance of pulmonary arterial pressure and diffusion capacity of the lung as prognosticators in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2007. March; 131( 3): 650– 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Castria D, Refini RM, Bargagli E, Mezzasalma F, Pierli C, Rottoli P.. Pulmonary hypertension in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevalence and clinical progress. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012. Jul-Sep; 25( 3): 681– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hayes D Jr, Higgins RS, Black SM, . et al. Effect of pulmonary hypertension on survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis after lung transplantation: an analysis of the United Network of Organ Sharing Registry. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015. March; 34( 43): 430– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zimmermann GS, von Wulffen W, Huppmann P, . et al. Hemodynamic changes in pulmonary hypertension in patients with interstitial lung disease treated with PDE-5 inhibitors. Respirology. 2014. July; 19( 5): 700– 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network, Zisman DA, Schwarz M, Anstrom KJ, Collard HR, Flaherty KR, Hunninghake GW.. A controlled trial of sildenafil in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2010. August 12; 363( 7): 620– 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hervé P, Lebrec D, Brenot F, . et al. Pulmonary vascular disorders in portal hypertension. Eur Respir J. 1998. May; 11( 5): 1153– 66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Plevak D, Krowka M, Rettke S, Dunn W, Southorn P.. Successful liver transplantation in patients with mild to moderate pulmonary hypertension. Transplant Proc. 1993. April; 25( 2): 1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoeper MM, Krowka MJ, Strassburg CP.. Portopulmonary hypertension and hepatopulmonary syndrome. Lancet. 2004. May 1; 363( 9419): 1461– 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krowka MJ, Plevak DJ, Findlay JY, Rosen CB, Wiesner RH, Krom RA.. Pulmonary hemodynamics and perioperative cardiopulmonary-related mortality in patients with portopulmonary hypertension undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2000. July; 6( 4): 43– 50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krowka MJ, Miller DP, Barst RJ, . et al. Portopulmonary hypertension: a report from the US-based REVEAL Registry. Chest. 2012. April; 141( 4): 906– 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Salgia RJ, Goodrich NP, Simpson H, Merion RM, Sharma P.. Outcomes of liver transplantation for portopulmonary hypertension in model for end-stage liver disease era. Dig Dis Sci. 2014. August; 59( 8): 1976– 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goldberg DS, Batra S, Sahay S, Kawut SM, Fallon MB.. MELD exceptions for portopulmonary hypertension: current policy and future implementation. Am J Transplant. 2014. September; 14( 9): 2081– 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ramasubbu K, Deswal A, Herdejurgen C, Aguilar D, Frost A.. A prospective echocardiographic evaluation of pulmonary hypertension in chronic hemodialysis patients in the United States: prevalence and clinical significance. Int J Gen Med. 2010. October 5; 3: 279– 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zlotnick DM, Axelrod DA, Chobanian MC, . et al. Non-invasive detection of pulmonary hypertension prior to renal transplantation is a predictor of increased risk for early graft dysfunction. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010. September; 25( 9): 3090– 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Naim I, Krowka M, Griffin M, Hickson L, Stegall M, Cosio F.. Pulmonary Hypertension Is Associated With Reduced Patient Survival After Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation. 2008. November 27; 86( 10): 1384– 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bal Z, Sezer S, Uyar ME, . et al. Pulmonary hypertension is closely related to arterial stiffness in renal transplant patients. Transplant Proc. 2015. May; 47( 4): 1186– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stallworthy EJ, Pilmore HL, Webster MW, . et al. Do echocardiographic parameters predict mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease? Transplantation. 2013; 95: 1225– 32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Butler J, Stankewicz MA, Wu J, . et al. Pre-transplant reversible pulmonary hypertension predicts higher risk for mortality after cardiac transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005. February; 24( 2): 170– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]