Abstract

Background:

Communication between parents and their children about parental life-limiting illness is stressful. Parents want support from health-care professionals; however, the extent of this support is not known. Awareness of family’s needs would help ensure appropriate support.

Aim:

To find the current literature exploring (1) how parents with a life-limiting illness, who have dependent children, perceive health-care professionals’ communication with them about the illness, diagnosis and treatments, including how social, practical and emotional support is offered to them and (2) how this contributes to the parents’ feelings of supporting their children.

Design:

A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis.

Data sources:

Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and ASSIA ProQuest were searched in November 2015 for studies assessing communication between health-care professionals and parents about how to talk with their children about the parent’s illness.

Results:

There were 1342 records identified, five qualitative studies met the inclusion criteria (55 ill parents, 11 spouses/carers, 26 children and 16 health-care professionals). Parents wanted information from health-care professionals about how to talk to their children about the illness; this was not routinely offered. Children also want to talk with a health-care professional about their parents’ illness. Health-care professionals are concerned that conversations with parents and their children will be too difficult and time-consuming.

Conclusion:

Parents with a life-limiting illness want support from their health-care professionals about how to communicate with their children about the illness. Their children look to health-care professionals for information about their parent’s illness. Health-care professionals, have an important role but appear reluctant to address these concerns because of fears of insufficient time and expertise.

Keywords: Health-care professionals, parental life-limiting illness, children, communication

What is already known about the topic?

Parents who have a life-limiting illness are anxious and uncertain about how best to communicate with their children.

Parents often do not receive support or guidance from health-care professionals (HCPs) about how to talk to their children about the illness.

Good familial communication about the illness improves children’s psychosocial functioning.

What this paper adds?

Parents, from diagnosis and throughout their illness, want support from HCPs about how best to communicate with their children and report a discrepancy between the desired support and what is provided by HCPs.

Children would welcome opportunities to discuss their parent’s illness with a HCP.

HCPs have concerns about time and expertise when supporting parents to talk with their children about the illness.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

During parental life-limiting illness, it is essential that parents and children are supported by HCPs involved in their care.

HCPs have an important role in supporting parents to have conversations with their children about their illness.

HCPs require adequate training in how best to communicate with parents and their children about life-limiting illness.

Background

It is estimated that 23,000 parents die in the United Kingdom each year; this equates to approximately 40,000 children per year being bereaved of a parent.1 Every aspect of family life has the potential to be disrupted following the diagnosis of serious illness, and during this period, children are exposed to significant levels of psychosocial stress.2–4 Furthermore, the disease becomes a feature of daily life for families, which requires pragmatic and psychological adaptation,5 with the whole family being at risk of psychological issues, including acute stress disorder.6 Parents experience increased anxiety because of uncertainty about how best to help their children and often receive little, if any, support or guidance from health-care professionals (HCPs) about how to approach this sensitive subject.7 However, it has been shown that good communication between HCPs and patients has a positive effect on their psychological adjustment to the illness.8

Although little is known about how parents tell their children that they are seriously ill and might die,9 good familial communication about the diagnosis improves children’s psychosocial functioning.10 Different factors may affect how children cope with their parent’s illness, including their age/level of cognitive maturity and the relationship with their parents.11,12

In providing information to patients and family members, HCPs should ensure that it is age appropriate and suitable for children and young people.13 Communication with children of parents who are dying is widely acknowledged as an important factor in supporting them during this time.12,14 Yet typically for HCPs, patients’ needs are paramount at the expense of other family members, and little is known about how discussing the impact of a life-limiting diagnosis will affect communication patterns between parents and their children.15,16 Moreover, HCPs often view working with families as one of the most difficult aspects of palliative care.17

There is currently limited empirical knowledge about the communication and information needs of children when a parent is dying.18 This includes how much information children want, how they would like the information to be given and by whom. Furthermore, the quantity and quality of information children currently receive about their parent’s terminal illness have not been adequately evaluated. The evidence that does exist indicates that children’s knowledge and understanding of their parent’s illness are often inaccurate as they gain information from overheard conversations or from third parties who do not necessarily know all the facts.14

For a parent with a life-limiting illness, to tell their child that they are dying is one of the hardest things they can do.19–21 This is also challenging for HCPs who often feel inadequately prepared to enter into such discussions with parents which results in poor or no communication.18,21 This is partly because HCPs struggle to understand the child’s perspective and might avoid talking to the patient about their children because of fear of distressing the parent.7,22 Although children’s quality of life diminishes when a parent has cancer,5 when families, experiencing parental cancer, engage in educative, emotional and social support, there are positive outcomes for all family members.5

The aim of this systematic review was to explore how parents with a life-limiting illness, who have dependent children, perceive HCP’s communication with them about their illness, diagnosis and treatments, including how social, practical and emotional support is offered to them, and how this contributes to the parents’ feelings towards supporting their children. A secondary aim was to identify what information and support families, including children, receive from HCPs with respect to communicating about the illness and the type and extent of information that would be helpful. This will contribute to an important gap in the evidence of how to improve the experiences of patients, their children and HCPs.

Methods

This systematic review followed an a priori protocol according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 guidelines.23 The review protocol was registered on the PROSPERO website (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO) before screening and data extraction (registration no. CRD42015029415).24

Search strategy

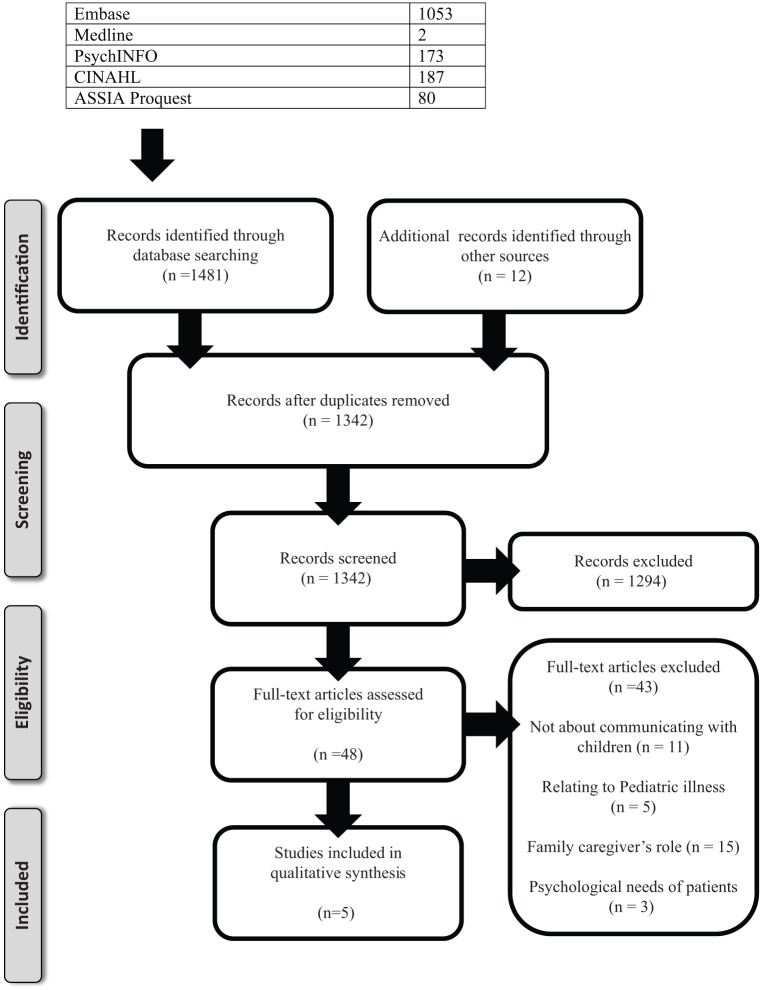

In November 2015, electronic searches were undertaken of Embase (1974–2015), Ovid MEDLINE®Daily Update 4 November 2015, PsycINFO (1967 to September Week 5, 2015), CINAHL (EBSCO HOST) and ASSIA ProQuest databases. Search strategies were devised to be inclusive of all potentially relevant studies using both Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and text word searches to increase the search sensitivity. Initially, a specific search strategy for MEDLINE was developed with the help of a university librarian search specialist (Table 1), this was adapted to the other databases. Reference lists of relevant articles were hand searched. Table 2 shows the inclusion/exclusion criteria adopted for the search. Children who have a life-limiting illness and parents with acute illness or trauma were excluded as the conversations, and the support these groups needed would be very different. Studies that provided data regarding communication between patients, who have dependent children and HCPs regarding supporting the children were included (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Example terms used in MEDLINE search strategy.

| 1. Life-limiting disease*.mp. 2. Life-limiting illness*.mp. 3. Serious illness*.mp. 4. Terminally ill/OR Terminal* ADJ ill*.mp. 5. Terminal* ADJ disease*.mp. 6. Terminal ADJ Care.mp. 7. Dying.mp. 8. Advanc* illness.mp. 9. Advanc* disease.mp. 10. Palliative Care/OR Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing OR Palliative.mp. |

11. Parent*.mp. 12. Adult.mp. 13. Mothers/OR mother*.mp. 14. Fathers/OR father*.mp. |

| 15. Communicat*.mp. 16. Informat*.mp. 17. Social support.mp. 18. Emotional support.mp. 19. Practical support.mp. 20. Family support.mp. 21. Psychosocial support.mp. |

22. Child*.mp. 23. Adolescen*.mp. 24. Dependent*.mp. 25. Offspring.mp. 26. Family.mp. |

| 27. Health professional*.mp. 28. Nurses/OR Nurse*.mp. 29. Doctor*.mp. 30. Consultant*.mp. 31. General ADJ Practitioners/OR General ADJ Practitioner* OR GP.mp. 32. Social worker*.mp. 33. Psychologist*.mp. 34. Counsel?or*.mp. |

35. = 1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 OR 9 OR 10 36. = 11 OR 12 OR 13 0R 14 37. = 15 OR 16 OR 17 OR 18 OR 19 OR 20 OR 21 38. = 22 OR 23 OR 24 OR 25 OR 26 39. = 27 OR 28 OR 29 OR 30 OR 31 OR 32 OR 33 OR 34 40. = 35 AND 36 AND 37 AND 38 AND 39 |

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Study design | |

| Qualitative and quantitative studies, observational studies, case–control studies and narrative research studies that describe communication between HCPs and parents about how to talk with their children about the parent’s illness | Case studies Opinion pieces |

| Participants | |

| Adult patients who have been diagnosed with a life-limiting illness who have children (aged <18 years). HCPs directly supporting children of patients with a life-limiting illness or indirectly by supporting the parent to help them support/communicate with their children about the illness |

Children who have been diagnosed with a life-limiting illness Patients who have adult children Patients who do not have dependent children Ill siblings Bereaved families Acute illness/trauma Patients receiving treatment in ITU/A&E |

| Interventions | |

| Studies describing or evaluating the effect of communication, information sharing or social and emotional support offered face to face to families by HCPs Studies reporting the effect of communication, information or social and emotional support, from HCPs, to family members including directly to the children Individual and group support Comparisons of patients who have received information from HCPs and those who have not Pre- and post-death interventions with the same families The terminal illness will be the result of different causes including cancers, heart/respiratory disease/failure, neurological diseases (MS, MND, stroke) |

Where the child has been diagnosed with a life-limiting illness Where siblings have a life-limiting illness Communication with the family post-bereavement Support offered to the family post-death Support not directly offered/delivered by a HCP |

| Setting | |

| There will be no restrictions by country | Health-care setting/location will exclude ITU and A&E |

| Date | |

| There will be no restrictions by date | |

| Language | |

| There will be no language restrictions for searching studies. Non-English language papers will be included in the review and every attempt will be made to translate all included foreign language papers. However, if translation is not possible, this will be recorded | |

HCPs: health-care professionals; ITU: intensive therapy unit; A&E: accident and emergency; MS: multiple sclerosis; MND: motor neurone disease.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Data extraction, assessment and analysis

Two authors (R.F. and J.W.B.) independently reviewed all titles and abstracts in order to assess their relevance for inclusion. Full-text papers were retrieved for all those fulfilling the inclusion criteria and also for publications which could not be excluded on the basis of the titles and abstracts alone. These authors then assessed the full texts of all potentially relevant studies. Disagreement at all stages was resolved by discussion and with recourse to an independent party, if needed. The findings are reported according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines, and the results of these searches and reasons for excluding the articles at the full-text stage are shown in the PRISMA Flow Diagram (Figure 1).25

R.F. and J.W.B. independently extracted data regarding study design and results and assessed their quality. Data extracted included type of study, participants, aims, objectives and study findings. The methodological quality of each study was independently assessed by R.F. and J.W.B. using the Hawker scale.26 The scale has nine questions about the validity, results and clinical relevance of the studies. The overall score for each study is between 9 (low quality) and 36 (high quality). Studies were not excluded on the grounds of poor quality, but this was to be taken into account during analysis.

Data were analysed using a narrative synthesis.27 This process facilitates the data synthesis of heterogeneous studies, such as the literature on communication between HCPs and parents about how to talk with children about parental illness. Three stages were undertaken by R.F. and J.W.B.: (1) development of a theoretical model of communication between HCPs and parents who have a life-limiting illness, (2) preliminary synthesis with an exploration of relationships in the data and (3) assessing the robustness of the final synthesis.27

Results

We identified 1342 unique studies from the searches. These were screened by title and abstract; 1294 studies did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded (Table 2; Figure 1). Full-text articles were reviewed for the remaining 48 studies. The reasons for excluding a full-text study are shown in the PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1). A narrative synthesis was carried out explaining the characteristics of the studies included; these explored the relationships and findings within and between included studies.

Five qualitative studies met our inclusion criteria representing a total of 55 ill parents, 11 spouses/carers, 26 children and 16 HCPs (Table 3). Three studies used semi-structured interviews,28–30 one involved in-depth interviews,19 one a structured telephone interview7 and one also included a focus group.29 Four studies focussed on parents who had cancer,7,19,28,30 the fifth interviewed one parent with terminal cancer and four bereaved parents whose partners had died from either cancer or non-cancer illnesses.29 Two studies included children29,30 and one also interviewed HCPs working with families pre- and post-parental death.29 Three studies were British,28–30 one Norwegian19 and one Australian.7

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Author Title Country Quality (Hawker Scale, range 9–36) |

Aims/objectives | Participants | Methods | Relevant findings | Strengths and limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barnes et al.28

Qualitative interview study of communication between parents and children about maternal breast cancer United Kingdom Hawker Score: 26 |

To examine parents’ communication with their children about the diagnosis and initial treatment of breast cancer in mothers | Mothers (n = 32) with stage I or II breast cancer, who had at least one child aged 5–18 years. | Semi-structured interviews | Most mothers began talking to their children after their diagnosis had been confirmed, whereas others were reluctant to reveal their illness to their children even after surgery. Mother’s wanted to avoid children’s questions, particularly those about death. Discussions were limited by parents being unclear what children could understand, how they would react and how to cope and respond when questions were asked. Few mothers received support from HCPs about how to talk with their children about the illness or the children’s possible reactions to the news. Many women wanted a HCP with experience in child development and communication with children and wanted to access this as a family. The authors concluded that parents would benefit from discussions with HCPs even if they chose not to communicate any details to their children. |

Good use of participant’s narratives which are clearly presented. The findings are transferable to other situations of loss and distress. Selection bias towards middle class occupations; this reflected the population for the community where the study was based. Only interviewed mothers with early breast cancer, so focused on communication at diagnosis and initial treatment. |

| Bugge et al.19

Parents’ experiences of a family support program when a parent has incurable cancer Norway Hawker Score: 27 |

Evaluation of a family support programme | Mothers (n = 1) and fathers (n = 3) who had been involved in a family support programme for parents with incurable cancer, who had at least one child between 5 and 18 years. Two parents agreed to participate but died prior to the interview. |

In-depth interviews | The programme helped increase parental insight into their children’s thoughts and reactions, as well as reduce conflicts within the family. Parents reported being able to talk more openly and developed skills to support their children’s coping. Patients and their partners had many concerns and anxieties about communicating with their children about the illness. Parent’s lack of knowledge and experience made them unsure about what was best for their children. Parents wanted support to help minimise any potential future problems for their children. Parents were concerned they would do their children harm by telling their children about the illness in a ‘wrong way’. Parents wanted guidance from HCPs about communicating with their children, including taking into account their ages and needs. |

Participant’s narratives used to support the findings. Provides clear recommendations for practice which can be used in multiple settings. Very small sample size and risk of sampling bias as the recruitment was via a single source. Discrepancy with the number of participants. No comparator group as all participants had received support from a family support programme. More information about context and setting required to increase generalisability. |

| Fearnley29

Supporting children when a parent has a life threatening illness: the role of the community practitioner United Kingdom Hawker Score: 28 |

To develop a greater understanding of the children’s lives when living with a parent who is dying | Interviews: Bereaved children (n = 7, aged between 9 and 24 years at the time of the interviews – 5 of which included interviews with their parents), bereaved parents (n = 4), terminally ill parent (n = 1), HCPs working with families pre- and post-death (n = 16). One focus group: bereaved children who attended a support group facilitated by a hospice (n = 8). |

Semi-structured interviews and focus group | The value of including children in conversations about parental illness and possible death is paramount. Children unanimously stated that being included in discussions and having an awareness of their parents’ illness based on fact is preferable to being excluded. HCPs were concerned that they would make the situation ‘worse’ by talking about it to children. HCPs were concerned that conversations would take ‘too much time’ and that talking about illness and possible death would open up ‘a cans of worms’. All professionals involved with the family have a responsibility in ensuring that children are involved in discussions and information sharing to the extent that they choose. |

Children’s and parent’s experiences are presented. The HCP’s perceptions are included in the findings. The findings are not presented clearly. More information about context and setting required to increase generalisability. |

| Kennedy and Lloyd-Williams30

Information and communication when a parent has advanced cancer United Kingdom Hawker Score: 29 |

To identify communication and information needs of children when a parent has advanced cancer. | Parents with advanced cancer, their carers and their dependent children from 12 families (7 of which included children): Ill parents (n = 10) Main carers (n = 7) Children (n = 11) |

Semi-structured interviews | Children wanted to know what was happening within their families during the illness and wanted honesty from their parents about the illness so that they could prepare for the future, but were reluctant to talk to their parents for fear of upsetting them. Children’s need for information varied with different stages of the disease, needing most information at diagnosis, with regard to the disease, treatments and tests. At later stages, there was more need for information regarding how to help their parents. Children wanted information from a variety of sources including parents, HCPs, books, leaflets, and the Internet and expressed a need to have access to somebody who understood and who would keep their conversations confidential. They identified HCPs as a valuable source of information and wanted to talk to HCPs about the illness but there were few opportunities to do so. When they did meet with HCPs, information was not age appropriate. Girls expressed a particular need for information regarding implications for their own health and possible future tests. Parents found it difficult to make the decision whether to tell their children or not about the illness. Parents were unsure how honest to be with their children; they had uncertainty about what to expect if they told their children (their children’s reactions) and were uncertain because of the age of their children. Parents found it difficult to answer their children’s questions about death as well as about treatment, tests and side effects. |

Children and parent’s views are presented. Risk of bias within the children sample as they had some knowledge about their parent’s illness. Did not describe their analysis methodology. More information about context and setting required to increase generalisability. Children’s ages/genders not reported Parents and main carers not differentiated, therefore difficult to determine specific views of each. |

| Turner et al.7

Development of a resource for parents with advanced cancer: what do parents want? Australia Hawker Score: 25 |

To develop a resource that could be widely distributed to parents when they are diagnosed with advanced cancer. | Mothers with breast cancer (n = 8) | Structured telephone interviews | Women received minimal assistance from HCPs about how to talk to their children about the diagnosis. Counsellors were not attuned to the women’s needs and lacked the details they felt they needed in coping with advanced cancer. All the women felt it was important to tell their children about their cancer at the point of diagnosis. The women described the need to help their children to maintain hope while being honest with them. The mothers felt that a brief information resource, given to them at the point of diagnosis of advanced disease would be helpful. They thought the brochure should include information about how to talk to their children about dying, examples of what other families have done to cope and things that might help children have a better outcome. |

The study considered communication at the time of early and advanced diagnosis. Participants were co-collaborators in the content and design of the subsequent resource. Small sample size and risk of sampling bias as recruitment was via a single source. Did not describe the methodology of analysis. Only included mothers. More information about the setting required to increase generalisability. |

HCPs: health-care professionals.

The Hawker scale was used to assess the methodological quality of the included studies.26 Scores of the five included studies ranged from 25 to 29 (Table 3), indicating that all were of moderate to good methodological quality. Limitations of the included studies are detailed in Table 3.

Three themes were identified within the studies; these were developed from the exploration of relationships within the data as part of the narrative synthesis.27 The themes were as follows:

The HCP’s involvement in discussions with parents;

Parents wanting help to tell their children about the diagnosis;

Telling children about the illness.

The health-care practitioner’s involvement in discussions with parents

There was a discrepancy between the support parents wanted and needed from HCPs about talking to their children, and what they received.7,19,28 Often HCPs avoided any discussions, with parents, about the impact of the illness on children or ways of talking about the diagnosis and its treatments.7,28 For some women with cancer, ‘this pattern of avoidance of discussion about children continued during treatment, often over many years’.7 When parents were offered support, this included being provided with a list of books for them to source and being offered contact with a social worker.7 Conversations between HCPs and parents, about the children, only occurred when the patients raised the subject themselves.7 Women wanted the opportunity to meet with a HCP, either with their partner or as a whole family, and that preferably this should be in their own home.28 In addition, they thought their children would benefit from talking directly to a HCP, for example, a nurse or surgeon.28

When support was not offered from HCPs, parents chose to access help from other sources including counsellors.7 However, women with cancer were often dissatisfied with the counselling service they received.7 Their concerns ranged from the counsellors not being sufficiently aware of the issues that women with breast cancer experience to the counsellor being too confrontational about their mortality. Some women looked to other resources, including books and pamphlets to find information about talking with their children about the illness. Here they encountered problems because the information was either unsuitable to their needs, that is, discussing early cancer when they were in the advanced stages, or was out of date or ‘very negative’.7

Parents wanting help to tell their children about the diagnosis

The included studies reported that most parents with a life-limiting illness wanted support from their HCPs about how they could best communicate with their children about the diagnosis, prognosis and treatments.7,19,28,30 However, some parents wanted HCPs to tell their children on their behalf, although they wished to maintain control over timing and content.30

In the study by Buffe et al., a family support programme was developed to help parents with incurable cancer, by helping the family to talk about the illness, helping parents to understand the needs of their children and how best to support them and to help the family plan for the future.19 Parents attending the group ‘knew this was a traumatic time for their children and wanted to prepare them and support them as best they could, but a lack of knowledge and experience made them unsure what was best for their children’.19 Therefore, one of the motivations for joining the group was an unmet need of wanting help with how to talk to their children about their illness.19

Mothers wanted information from HCPs about how to break bad news to their children and advice about the most appropriate language to use.7,28 After they had spoken to their children, they then wanted reassurance from HCPs that they had communicated and supported the former in the best way.7,19 Mothers also wanted recommendations and practical support from HCPs about involving and familiarising their children with the medical environment and with their treatment.7,28 They thought it was important for their children to be included as they believed this would help to demystify treatment and help them understand what was happening.7 None of the women described receiving any professional recommendations about involving their children in treatments.7

Telling children about the illness

Parental experiences of telling children about their diagnosis and prognosis were discussed in all of the included studies.7,19,28–30 Mothers with breast cancer reported that it was important to tell their children at the time of diagnosis and continue to communicate with them throughout their illness.7,28 Although the study by Bugge et al. study had not spoken to their children about the diagnosis until they had attended a support programme, they expressed relief in being given HCP support to find ways to talk with their children.19 Parents reported that telling their children about the diagnosis was one the most difficult issues they experienced.30

Children wanted to communicate with their parents about the illness but often did not because of not wanting to upset them or because they did not know how to go about it.30 Because of this, the children identified HCPs, as a valuable source of information; however, they described how there was generally a lack of opportunities to meet with them, which was problematic.30

Children wanted to know what was happening so that they could begin to prepare for the future.30 However, some of the children reported not being fully informed about the diagnosis and/or prognosis.30 Children’s need for information varied throughout their parent’s illness, with the initial stages being the time when they wanted most information, particularly in relation to the disease, treatments and tests.30 Children spoke about how they wanted and actively sought opportunities to talk about what was happening, but were often obstructed by parents and HCPs.29

HCPs and social-care professionals reported that they themselves and parents often found it difficult to talk to children about the illness because of fear of upsetting them, thinking that they will be too young to understand and not knowing what to say.29 In addition, they reflected that professionals are often concerned that the conversations will take too much time, that they will open up a ‘can of worms’ which they, the professionals, will be unable to manage and make it worse.29 However, one professional observed that ‘the worst had actually happened [the diagnosis of a life-limiting illness] and no amount of protection could prevent it from being any worse’.29

Discussion

This is the first systematic review of studies exploring parent’s perceptions about how HCPs communicate with them following the diagnosis of a life-limiting illness. Parents want and need information and guidance from HCPs, at the point of diagnosis and throughout their illness, about how to talk with and support their children about the illness.7,19,28–30 Telling their children that they are dying was one of the most difficult tasks for parents with a life-limiting illness,19–21 especially when parents are concurrently dealing with their own reactions and the needs of their children.21 This review demonstrated a discrepancy between the support parents wanted and what they received.7,19,28,29

The review has shown the importance that ill parents placed on wanting to have coordinated and managed discussions with their children about the illness, but that they were unsure how to do it in the most appropriate way.7,19,28,30 This correlates with previous studies that have discussed the importance and relevance of support from HCPs to help parents begin to have such conversations.31,32 When parents had discussed the illness with their children, and ‘followed their instincts’,7 they then wanted reassurance from their HCPs that they had given information appropriately.7,19 This would suggest that parent’s perceive the HCPs’ role to go beyond the parameters of clinician and to extend into a supportive role too. Moreover, it highlights the important role HCPs have in providing holistic care to the patient. This holistic role was also noted by children in the studies who expressed the desire to meet with their parent’s HCPs.29,30 They too wanted the opportunity to explore illness-related issues with people who they perceived would be valuable sources of information (e.g. doctors and nurses).30 Research has shown that the quality of life diminishes for children when a parent has cancer,5 and so to receive support from people who they trust and identify as being knowledgeable about the situation is likely to have a positive effect on their well-being.

The findings from this review build upon previous work that has studied the communication needs of patients with dependent children.9,16,18,31,33–36 It has been shown that although parents are often the best people to talk to their children about the illness, they need considerable guidance from HCPs to start and manage these conversations.31,32 HCPs need to appreciate the family’s unique situation when discussing issues of disclosure9 and be aware that parents not only face the challenge of coping with the illness and its treatments but also the challenges of meeting their children’s needs.32 Parents may fail to recognise or respond to the emotional distress of their children.37 HCPs, therefore, have a responsibility to consider the family unit as a whole,31 recognising that what happens to the patient has a direct impact on all members of the family.31 It also needs to be recognised that what happens to the family will have a direct impact on the patient.

However, when clinicians do not perceive it is their role to deal with psychosocial concerns, they are less likely to encourage any communication on the topic.38 The review has shown that HCPs have concerns about discussing children with parents and indicates that they need to support themselves in order to enhance the experience of parents with a life-limiting illness and their families. This would indicate that there is a need for additional training and support for HCPs to help manage these complex situations. This review has illustrated that parents and children would welcome information from HCPs, and this can encompass specialist nurses, oncologists, consultants and palliative physicians.

Children’s views were explored in only two of the studies,29,30 and these are consistent with previous research that has shown how important it is for children to be prepared and informed about their parent’s terminal illness12,18,39,40 and the necessity for them to be included in conversations.2,12,39,40 Furthermore, communication with children helps to reduce their anxieties about what is happening within their families.41 This review consolidates the importance of communication, specifically in relation to the role HCPs have in helping to facilitate conversations between parents and children.

One included study also explored communication from the HCP’s perspective.29 It identified concerns from HCPs that discussions with parents and/or their children would ‘take too much time’ which might be a barrier preventing these conversations from being held.29 Time is known to be a barrier for communication with families by HCPs,38 and HCPs have reported that working with families is one of the most difficult aspects of working with people who have a life-limiting illness.17 Although this can be difficult and time-consuming, parents clearly want and need this support from HCPs.7,19,28–30

Strength and limitations

This is the first systematic review in this field. Although qualitative studies are not designed to be representative at the population level, and the number of included studies are few, the themes arising from the data are remarkably similar even though the studies were conducted in three countries (United Kingdom, Norway and Australia), albeit countries with similar cultural approaches to individual autonomy and disclosure of a diagnosis of a life-limiting illness.

The included studies were predominately mothers who had breast cancer; therefore, the perceptions were drawn from a particular set of clinical needs and are not necessarily generalisable to all illnesses and diseases. Information on what fathers wanted was limited as were the views of the non-ill parents, who it is likely, would have different concerns and needs in relation to communicating with and supporting their children. There was limited evidence found in relation to the HCP’s perceptions of communicating with patients about their children, thus limiting the scope of the review. This is partly due to only one study including HCPs. Despite using a robust systematic review methodology, with broad search terms, there was no literature available that directly explored practical support provided by HCPs to families. Only one study assessed the emotional and social support given to families by HCPs. It is possible that studies were missed, despite a rigorous search methodology and screening process being applied.

Implications for current practice

Our review has highlighted that there is a disparity between what parents and children want, from their HCPs, and what they receive. The most obvious barrier from this work appears to be that HCPs feel too time-pressured and inexpert to address these concerns. Additionally, the expectation is that adult palliative care clinicians are the ones who engage in these conversations, and they may not have had the same extent of training in communicating with children as their paediatric colleagues. It is also apparent that a reliance on printed information and guidance leaflets, or a non-medical counsellor, does not appear to be able to replace the individually tailored approach facilitated by a skilled practitioner with knowledge of the relevant medical issues. Clinical practice would be enhanced, if HCPs had appropriate training to develop their confidence in working with families. From this additional support, it is likely that parents would feel assured that they were supporting their children appropriately, this would then alleviate some of their stress which could benefit their well-being and have a positive impact on their treatment.

Future research

The review has highlighted that HCPs are often reticent to initiate conversations with parents about their children because of perceived difficulties and the implications of time. Research into training HCPs in communication with parents about their children regarding serious illness in this setting is needed. The benefit of HCPs systematically including discussions about children into their consultations with patients needs to be formally evaluated. This should include participants from different social classes and more diverse ethnic/cultural backgrounds.19 We hypothesise that parents who receive direct support from their HCPs about supporting their children will be physically, emotionally and psychologically better able to cope with the illness and treatments because of being less anxious about their children. The initial time invested by the HCPs would potentially reduce the overall time they needed to spend with the parents. The major potential positive outcome would be that children and their families would have better coping mechanisms throughout the illness and into the bereavement period.

Conclusion

This review has shown that parents, at the point of diagnosis and throughout their life-limiting illness, want and need reassurance and support from HCPs about how best to communicate with their children. Parents report a discrepancy between their desired support and what is provided by HCPs, often struggling to know how best to talk to their children about the illness, which compounds an already stressful situation. HCPs have an important role in facilitating these conversations and utilising their knowledge, skills and experience to help families and to potentially minimise the stress that parents and children experience. HCPs are reluctant to initiate conversations as they find them difficult and time-consuming, indicating that they also need training and support in order to do this, which will enhance the experience of parents with a life-limiting illness and their family.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Fiona Ware, Librarian, University of Hull, for her assistance with the search strategy and Prof. Miriam Johnson and Dr Julie Seymour, University of Hull, for their input with finalising the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Child Bereavement Network, 2015, http://childhoodbereavementnetwork.org.uk/research/key-statistics.aspx (accessed 12 December 2015).

- 2. Thastum M, Johansen MB, Gubba L, et al. Coping, social relations, and communication: a qualitative study of children of parents with cancer. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2008; 13(1): 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Giesbers J, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Van Zuuren FJ, et al. Coping with parental cancer: web-based peer support in children. Psychooncology 2010; 19: 887–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kennedy VL, Lloyd-Williams M. How children cope when a parent has advanced cancer. Psychooncology 2009; 18(8): 886–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Werner-Lin A, Biank NM. Along the cancer continuum: integrating therapeutic support and bereavement groups for children and teens of terminally ill cancer patients. J Fam Soc Work 2009; 12(4): 359–370. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gotze EJ, Brahler E, Korner A, et al. Quality of life of parents diagnosed with cancer: change over time and influencing factors. Eur J Cancer Care 2012; 21: 535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turner J, Clavarino A, Yates P, et al. Development of a resource for parents with advanced cancer: what do parents want? Palliat Support Care 2007; 5: 135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fallowfield LJ, Hall A, Maguire P, et al. Psychological effects of being offered choice of surgery for breast cancer. BMJ 1994; 309: 448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sheehan DK, Draucker CB, Christ GH, et al. Telling adolescents a parent is dying. J Palliat Med 2014; 17(5): 512–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Osborn T. The psychosocial impact of parental cancer on children and adolescents: a systematic review. Psychooncology 2007; 16: 101–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dent A. Theoretical perspectives: linking research with practice. In: Monroe B, Kraus F. (eds) Brief interventions with bereaved children, 1st ed Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Christ GH, Christ AE. Current approaches to helping children cope with a parent’s terminal illness. CA Cancer J Clin 2006; 56(4): 197–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nationals Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Improving supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer, 2004, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/csg4 (accessed 2 December 2015).

- 14. Fearnley R. Communicating with children when a parent is at the end of life. London: Jessica Kingsley, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dunning S. As a young child’s parent dies: conceptualizing and constructing preventive interventions. Clin Soc Work J 2006; 34(4): 499–514. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huizinga GA, Visser A, Van Der Graaf WTA, et al. The quality of communication between parents and adolescent children in the case of parental cancer. Ann Oncol 2005; 16: 1956–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. King DA, Quill T. Working with families in palliative care: one size does not fit all. J Palliat Med 2006; 9(3): 704–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fearnley R. Death of a parent and the children’s experience: don’t ignore the elephant in the room. J Interprof Care 2010; 24(4): 450–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bugge KE, Helseth S, Darbyshire P. Parents’ experiences of a Family Support Program when a parent has incurable cancer. J Clin Nurs 2009; 18: 3480–3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Buxbaum L, Brant JM. When a parent dies from cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2001; 5: 135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. MacPherson C. Telling children their ill parent is dying: a study of the factors influencing the well parent. Mortality 2005; 10(2): 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chowns G. ‘No, you don’t know how we feel’: groupwork with children facing parental loss. Groupwork 2008; 18(1): 14–37. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015; 349: g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, et al. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2012; 1: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6(7): e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, et al. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 2002; 12(9): 1284–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Lancaster: Lancaster University, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barnes J, Kroll L, Burke O, et al. Qualitative interview study of communication between parents and children about maternal breast cancer. West J Med 2000; 173(6): 385–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fearnley R. Supporting children when a parent has a life-threatening illness: the role of the community practitioner. Community Pract 2012; 85(12): 22–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kennedy VL, Lloyd-Williams M. Information and communication when a parent has advanced cancer. J Affect Disord 2009; 114: 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hockley J. Psychosocial aspects of palliative care: communications with the patient and family. Acta Oncol 2000; 39(8): 905–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Forrest G, Plumb C, Ziebland S, et al. Breast cancer in the family – children’s perceptions of their mother’s cancer and its initial treatment: qualitative study. BMJ 2006; 332: 998–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bugge KE, Helseth S, Darbyshire P. Children’s experiences of participation in a family support program when their parent has incurable cancer. Cancer Nurs 2008; 31(6): 426–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Elmberger E, Bolund C, Lutzen K. Experience of dealing with moral responsibility as a mother with cancer. Nurs Ethics 2005; 12(3): 253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fearnley R. Writing the ‘penultimate chapter’: how children begin to make sense of parental terminal illness. Mortality 2015; 20(2): 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Turner J, Kelly B, Swanson C, et al. Psychosocial impact of newly diagnosed metastatic breast cancer. Psychooncology 2005; 14(5): 396–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Turner J. Children’s and family needs of young women with advanced breast cancer: a review. Palliat Support Care 2004; 2: 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ryan H, Schofield P, Cockburn J, et al. How to recognize and manage psychological distress in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care 2005; 14: 7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Christ GH. Impact of development on children’s mourning. Cancer Pract 2000; 8(2): 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rauch PK, Muriel AC, Cassem NH. Parents with cancer: who’s looking after the children? J Clin Oncol 2002; 20(21): 4399–4402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Beale EA, Sivesind D, Bruera E. Parents dying of cancer and their children. Palliat Support Care 2004; 2: 387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]