Abstract

Background

Increased interest in radiation dose reduction in neurointerventional procedures has led to the development of a method called “spot fluoroscopy” (SF), which enables the operator to collimate a rectangular or square region of interest anywhere within the general field of view. This has potential advantages over conventional collimation, which is limited to symmetric collimation centered over the field of view.

Purpose

To evaluate the effect of SF on the radiation dose.

Material and Methods

Thirty-five patients with intracranial aneurysms were treated with endovascular coiling. SF was used in 16 patients and conventional fluoroscopy in 19. The following parameters were analyzed: the total fluoroscopic time, the total air kerma, the total fluoroscopic dose-area product, and the fluoroscopic dose-area product rate. Statistical differences were determined using the Welch’s t-test.

Results

The use of SF led to a reduction of 50% of the total fluoroscopic dose-area product (CF = 106.21 Gycm2, SD = 99.06 Gycm2 versus SF = 51.80 Gycm2, SD = 21.03 Gycm2, p = 0.003884) and significant reduction of the total fluoroscopic dose-area product rate (CF = 1.42 Gycm2/min, SD = 0.57 Gycm2/s versus SF = 0.83 Gycm2/min, SD = 0.37 Gycm2/min, p = 0.00106). The use of SF did not lead to an increase in fluoroscopy time or an increase in total fluoroscopic cumulative air kerma, regardless of collimation.

Conclusion

The SF function is a new and promising tool for reduction of the radiation dose during neurointerventional procedures.

Keywords: X-ray, collimation, digital subtraction angiography (DSA), neurointervention, fluoroscopy, dose saving

Introduction

Prolonged neurointerventional procedures lead to an increased risk of erythema and hair loss in patients and, indirectly, to increased ionizing radiation exposure in staff (1,2). Conventional collimation of X-rays was one of the first systems that reduced the X-ray dose, and it has been used almost since the introduction of X-rays in medicine. One of disadvantages of this system is a symmetric shielding of the field of view (FOV). A new fluoroscopic technology based on better focusing and collimation of X-rays that enables an asymmetric collimation at any size anywhere in the image has been developed and integrated into the Infinix™-i biplane system. The collimated, rectangular area can be resized and/or repositioned easily as often as necessary to obtain an optimal FOV. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of this novel technique, referred to as spot fluoroscopy (SF), on the total fluoroscopic time and on the fluoroscopic radiation dose to the patients. Dose area product (DAP) and DAP rate were of particular interest because they have been shown “to correlate well with the total energy imparted to the patient, which is related to the effective dose” and therefore with all irradiation-induced damage to normal tissues (3).

Material and Methods

The local ethics committee approved the study. The patients with unruptured aneurysms had oral and written information and consented to share their data for research. The consent was obtained from the next of kin when a patient was unconscious which is in accordance with ethical permissions.

Our study was designed as a prospective, randomized, single-center study. We intended to enroll a total of 25 patients with ruptured and unruptured cerebral aneurysms in each group. The interventions, collection and analysis of data started on 31 May 2013 and stopped on 2 October 2013. The collecting of data was stopped when analysis of results clearly showed that dose reduction achieved by SF is superior compared to the conventional system.

Sixteen patients (6 men: mean age, 60.8 years; 10 women: mean age, 53.3 years) were treated by using SF and 19 patients (11 men: mean age, 49.4 years; 8 women: mean age, 54.1 years) by using CF (further in the text CF group of patients and SF group of patients).

The Infinix™-i (Toshiba Medical Systems, Tochigi, Japan) has been in service and continuously upgraded since December 2011. This system is a biplane system using a 30 × 30 cm flat panel detector on each plane, with a pixel size of 194 µm, and the data are acquired on the frontal and/or lateral plane. SF is a commercially available software feature that is incorporated into the Infinix™-i system. The SF function including the necessary hardware and software components was installed in the second half of 2012. The efficacy in dose reduction by using SF was checked during 2013. The operators have used either conventional fluoroscopy (CF) or SF, in which case the CF is used only for the creation of last image hold (LIH). The same interventionists operated the system during the entire study (LB, EM, CN). The duration of fluoroscopy and all dose parameters were automatically recorded for each patient.

The endovascular coil occlusion of cerebral aneurysms has already been described elsewhere (4).

Spot fluoroscopy

Technical characteristics of fluoroscopy were: a detector input dose of 0.45 µGy/s for a reference FOV of 30 × 30 cm. FOV used was 15 × 15 cm, 20 × 20 cm, and 30 × 30 cm. The X-ray factors were: voltage, 80 Kv; range of current, 50–200 mA; and filtration, 0.3 mm copper. Current (mA) and time (ms) are not constant in fluoroscopy as they vary according to the automatic brightness control (ABC) response.

The Infinix system disposes two fluoroscopy modalities: CF and SF. SF is a novel function aimed at reducing the radiation dose to patients and staff during long-lasting, complex interventions (5). The function is based on flexible collimation capabilities combined with a novel ABC technique.

A novel collimator was developed that enables an independent control of the collimator blades so that any collimation of interest can be achieved anywhere in the image. In addition, a true virtual collimation function was implemented. The operator can virtually define his collimation of interest on the LIH by choosing from three predefined regions of interest (ROI) sizes (ROI default sizes can be predefined) and shapes (square or rectangular can be predefined) or by freely defining the collimation desired by two simple mouse clicks pointing on the two diagonal corners (upper left–lower right or upper right–lower left) of the potential ROI (Fig. 1). As soon as the collimation of interest is confirmed by a press on the joystick, the collimator blades are positioned accordingly in real time, and the last image hold is superimposed over the collimated part to preserve the anatomical and/or device-relevant information during the fluoroscopic operations that would normally be hidden by the collimator blades (Figs 1 and 2). This technique allows applying an asymmetric collimation anywhere in the LIH and can easily be operated at tableside via an integrated joystick. The replacement of SF by CF and vice versa can be done instantly by a simple changing of foot pedals.

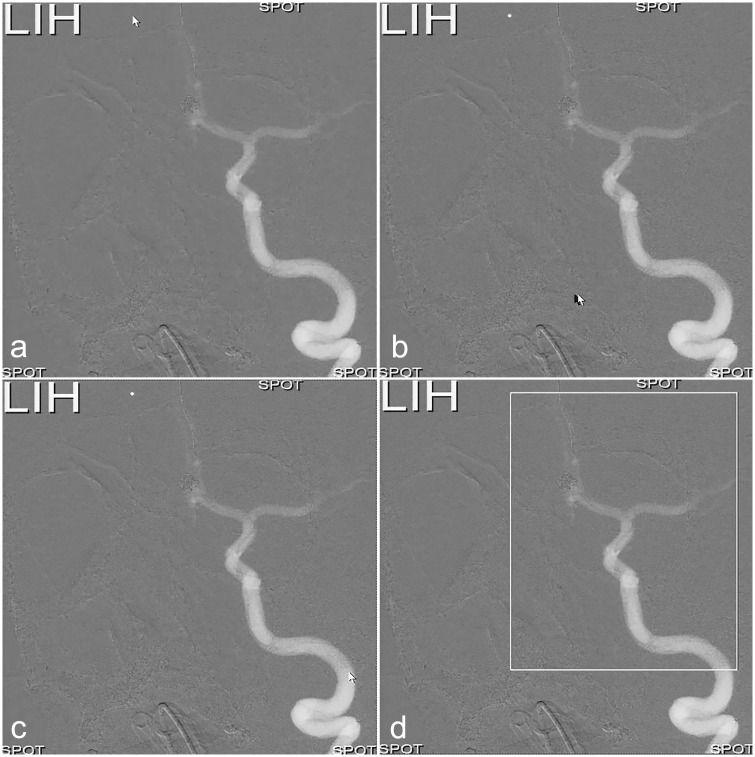

Fig. 1.

(a) White arrow indicates the upper left corner of the ROI. (b) The upper left corner is defined, and the arrow is being moved to the lower right corner. (c, d) ROI is now defined, and only this part of the FOV, outlined by the white-lined frame, will be exposed to irradiation; the LIH (upper left corner) will be superimposed over the collimated part of the FOV. “Spot” in each corner indicates that SF will be activated.

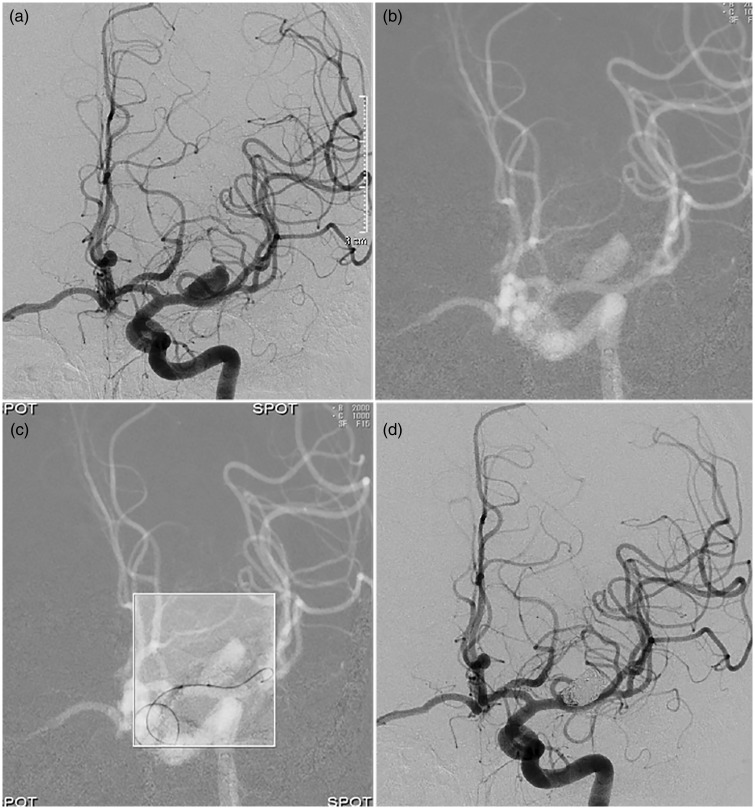

Fig. 2.

(a) Angiography of left internal carotid artery shows an aneurysm localized proximally on the M1 segment. (b) Conventional fluoroscopic road map used for creation of last image hold. (c) LIH in the left upper corner is no longer displayed – compare with Fig. 1, definition of the FOV. “Spot” in each corner indicates that SF is now activated – only the region inside the white-lined frame is exposed to radiation. Image shows positioning of balloon in front of the aneurysm. (d) Angiography of left internal carotid artery, last run, shows occluded aneurysm and minimal flow in the neck region of the aneurysm.

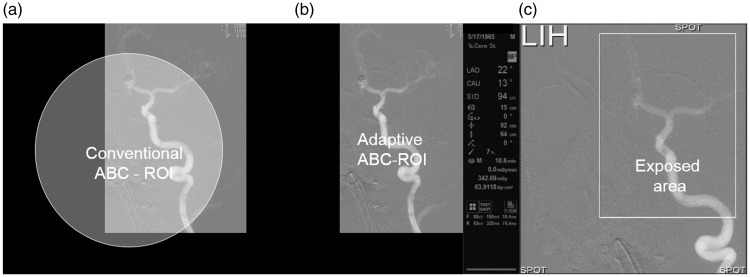

Because asymmetric collimation as such would always lead to a partial shielding of the ABC-ROI by the collimator blades and cause a falsification of the ABC brightness interpretation that would result in a dose increase, a novel advanced ABC technique was developed. A real-time collimation adaptive ABC-ROI adjustment algorithm was implemented (Fig. 3) (5,6).

Fig. 3.

(a) A situation where rectangular ROI does not correspond to a conventional circular sensing area. (b) ROI and sensing area have the same, rectangular shape and completely correspond to each other. (c) Important technical parameters are displayed to the left of the fluoroscopic image. The size and position of the rectangular ROI exposed to irradiation can be changed at any moment during the intervention depending on the size, shape, and position of the targeted vascular structure.

The following parameters were automatically recorded by the system during the intervention:

‐ Total fluoroscopic DAP;

‐ Total fluoroscopic DAP rate during fluoroscopy (DAP rate);

‐ Total fluoroscopic air kerma at the interventional reference point (IRP); and

‐ Total time of fluoroscopy in frontal and lateral planes.

The data were extracted from the system using Toshiba Medical Systems software.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of data was made with Welch’s t-test from GraphPad Software (GraphPad Software, GraphPad Prism Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Microsoft Excel 2015 – T TEST function was used for P value calculation with following references for statistical significance:

P value = 0.05 was defined as reference for statistical significance;

P value ≥0.05 indicated no statistically significant difference between the two groups; and

P value <0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference between the two groups.

Results

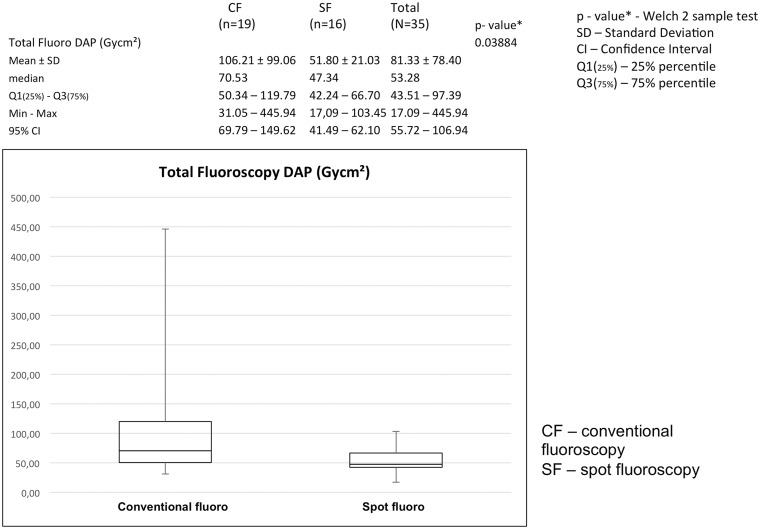

Total fluoroscopic DAP

SF reduced the total fluoroscopic DAP significantly, from 106.21 Gycm2 with a standard deviation of 70.53 Gycm2 to a total fluoroscopic DAP of 51.80 Gycm2, with a standard deviation of 21.03 Gycm2. The P value was 0.03884, calculated with Welch’s t-test (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

SF leads to a significant reduction of the fluoroscopic dose area product (Gycm2), P = 0.03884.

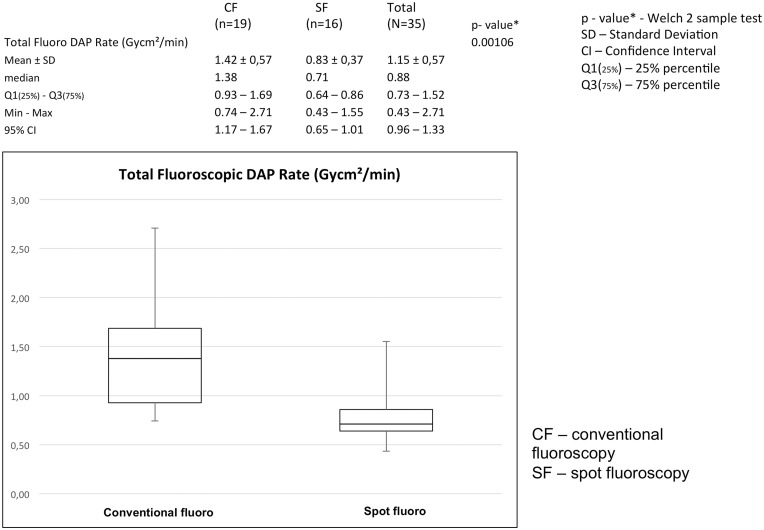

Total fluoroscopic DAP rate (DAP/min fluoroscopy time)

The total fluoroscopic DAP rate showed an even more statistically significant difference between the two groups, 1.42 Gycm2/min (SD = 0.57 Gycm2/s) for CF versus 0.83 Gycm2/min (SD = 0.37 Gycm2/min) for SF with a P value of 0.00106. The total fluoroscopic DAP and the total fluoroscopic dose rate are the most important parameters indicating the total radiation dose delivered to the target and the rate of delivery of the dose. Figs 4 and 5 show that the DAP and DAP rate in the SF group were significantly lower than in the CF group.

Fig. 5.

SF leads to a significant reduction of total fluoroscopic dose area product per minute (Gycm2/min), P = 0.00106.

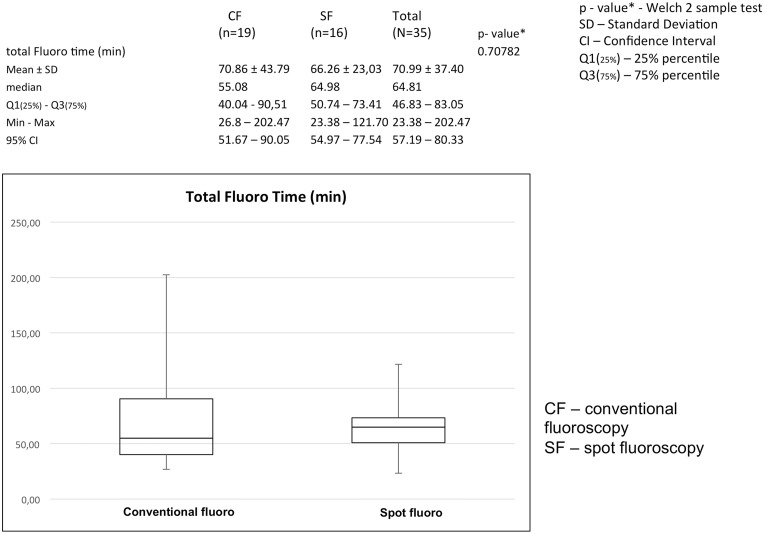

Total time of fluoroscopy (s)

We compared the mean total fluoroscopic time in two examined groups of patients to determine whether the use of SF as described in the previous section contributed to a prolongation of the time of intervention. As shown in Fig. 6, the total fluoroscopic time in the two examined groups of patients did not differ significantly, P = 0.70782 (Welch’s t-test).

Fig. 6.

SF does not lead to increase of fluoroscopy time (min). Difference between the values of fluoroscopy times is not significant, P = 0.70782.

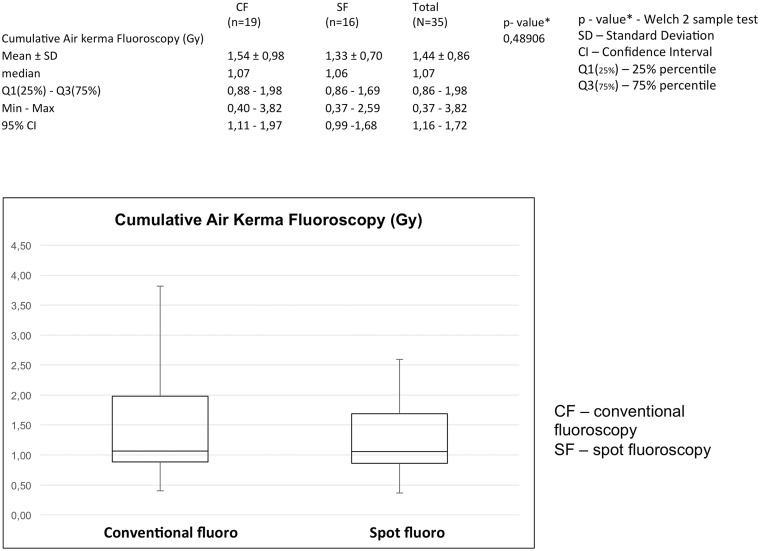

Fluoroscopic air kerma at IRP (mGy)

As shown in Fig. 7, the mean air kerma at IRP in the conventional fluoroscopy group was 1.54 Gy, SD = 0.98 Gy and 1.33 Gy, SD = 0.7 Gy in the SF group. There were no significant differences between these two values (P = 0.48906).

Fig. 7.

SF does not lead to an increase of total fluoroscopic air kerma (Gy). Difference between values of total fluoroscopic air kerma is not significant, P = 0.48906.

Discussion

The total time of fluoroscopy depends not only on the complexity of the intervention but also on the complexity of the handling of the system and image quality. Our results confirm that the handling of SF, switching on and off SF, adjustment of the FOV as well as quality of fluoroscopic image did not significantly affect the duration of the intervention.

The air kerma is an acronym for kinetic energy released per unit mass (or air) and expresses the radiation concentration delivered to a point, such as the entrance surface of a patient’s body (6). The size and the form of the target, which in our series is the vasculature containing the aneurysm, vary greatly from case to case. These parameters of the target determine the optimal size and form of the ROI necessary for safe intervention.

Beam collimators are one of the first systems for reduction of X-ray dose and have been used in radiology almost since the beginning of the X-ray era. Collimators are lead shutters installed in the X-ray tube housing parallel with a system of lamps and mirrors in such a way that a beam of light indicates the area on the skin that is exposed to the X-rays during fluoroscopy and fluorography. Though very effective, conventional collimation has considerable disadvantages:

Only symmetric collimation is possible, which leads to an unnecessary exposure for larger anatomical areas than actually needed;

Anatomical and/or device-relevant reference information is lost;

Patient skin dose is increased when collimating inside the ABC-ROI (6).

The goals of the development of the SF system were to overcome these limitations of conventional collimation.

Conventional shielding may provide symmetric reduction of the size of the FOV, which is often not satisfactory because the geometry of the target is irregular. Therefore, in many situations the shielding is suboptimal and relatively large areas are exposed to irradiation. In contrast, SF provides very flexible and adaptable collimation regardless of the size and the form of the target without increasing the air kerma that would have occurred if the conventional ABC system had been applied. This fundamental difference is based on following three technical solutions: histogram-based attenuation profile analysis for optimal image brightness computation; dynamic real-time adaptation of size and location of the sensing area for brightness detection and computation; and detector input dose reduction proportional to the back scatter radiation saved by the collimation (5).

In other words, the reduction of the DAP and DAP rate is now consequently proportional to the reduction in the size of the area exposed to the radiation. With conventional collimation and dose rate control, the dose rate increases if the area of the automatic dose control becomes shielded by the collimators as well if asymmetric collimation is used in combination with a central position of the automatic dose control area (Fig. 3). With SF, the area of the automatic dose control is adapted to the actual X-ray collimation. The results of the measurements of DAP and DAP rate confirm that the dose rate does not increase using SF, including asymmetric collimation of the X-ray field.

All parameters, the fluoroscopy time, the mean air kerma at IRP, DAP, and DAP rate, reported in this study have been compared to data available in the scientific literature (1,7–16) (Table 1). Comparison of our results and results of these studies is problematic due to differences in patient populations and methodologies. Moreover, some of the studies do not report the air kerma at IRP and DAP values from fluoroscopy and DSA separately (7–11). We have therefore focused our interest on analysis of fluoroscopic DAP and especially on fluoroscopic DAP rate (Gycm2 /min). In an optimization study by Söderman et al. (1), the mean DAP was reduced by 35%, from 84.5 Gycm2 to 55 Gycm2, and the mean air kerma at IRP by about 60%, from 3.5 Gy to 1.3 Gy. Our study shows that SF has reduced the fluoroscopic DAP by 50%, which is comparable with the results of Söderman et al.’s study (1). The reason why the IRP did not change as much as in Söderman et al.’s study is that SF does not affect the skin dose, because it is kept constant. The only remarkable difference in radiation dose is that the fluoroscopic DAP decreases with SF, which agrees well with how the SF system is designed to work. In Söderman et al.’s study, the fluoroscopic DAP and mean fluoroscopic time even after optimization of the system indicates a high DAP rate in comparison with our results.

Table 1.

Comparison of results: This study versus others.

| Reference | Year | Mean DAP (Gycm2) | Mean air kerma at IRP (Gy) | Mean fluorotime | Mean DAP rate (Gycm2/min) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study, no SF | 2016 | 114.71 | 1.5 | 74.77 | 1.44 | Fluoro only, neurointervention of ruptured and non-ruptured aneurysms |

| This study, SF | 2016 | 51.79 | 1.3 | 66.25 | 0.82 | Fluoro only, neurointervention of ruptured and non-ruptured aneurysms |

| Söderman et al. (1) | 2013 | 85.40* | 3.5† | 12.5 | NA | *Fluoro only, before optimization, various cerebral interventions †Total fluoro and DSA |

| Söderman et al. (1) | 2013 | 55.00* | 1.3† | 11 | NA | *Fluoro only, after optimization, various cerebral interventions †Total fluoro and DSA |

| O’Dea et al. (7) | 1999 | NA | 2.1 | NA | NA | Various cerebral interventions, fluoroscopy, and DSA |

| Miller et al. (8) | 2003 | 281.57 | 3.8 | 74 | NA | Total fluoro and DSA, neurointervention |

| D’Ercole et al. (9) | 2010 | 382.8 | NA | 37 | NA | Total fluoro and DSA, neurointervention (treatment of aneurysms and AVMs) |

| Vano et al. (10) | 2013 | 305 | 2.7 | NA | NA | Total fluoro and DSA, various cerebral interventions |

| Kahn et al. (11) | 2015 | 347 | 3.65 | 41.1 | NA | Total fluoro and DSA, before optimization, neurointervention |

| Kahn et al. (11) | 2015 | 150 | 1.65 | 51.1 | NA | Total fluoro and DSA, after optimization, neurointervention |

| Kemerink et al. (12) | 2002 | 100.32 | 34.8 | NA | Fluoro only, neurointervention | |

| Alexander et al. (13) | 2010 | 172.30/NA | NA/3.1 | 37/68 | NA | Fluoro only, two systems intervention of ruptured and non-ruptured aneurysms |

| Urairat et al. (14) | 2011 | 147.4 | 1.47 | 40.1 | NA | Fluoro only, neurointervention |

| Han et al. (15) | 2013 | 256.3 | NA | 51.1 | NA | Fluoro only, neurointervention, group with special protection |

| Han et al. (15) | 2013 | 286.4 | NA | 61.5 | NA | Fluoro only, neurointervention, group without special protection |

| Theodorakou et al. (16) | 2014 | 74 | 1.3 | 44.9 | NA | Fluoro only, neurointervention |

DAP, dose area product; IRP, interventional reference point; NA, not available.

We have observed that the reported DAPs have progressively decreased since 2002 thanks to new technical solutions regarding X-ray generators, continuous optimization of hardware and software for data acquisition and image generation, as well as improvements in radiation protection systems integrated into the X-ray equipment, (1,12–16) (Table 1). The mean DAP that we measured shows that our system generates the lowest radiation compared to the results of these authors. The mean DAP rate has not been shown or analyzed separately in these studies. However, the comparison of values of mean DAP and mean fluoroscopic time reported in these studies with corresponding values in our study indicates that SF ensures by far the lowest dose area product rate (Table 1).

This study has definitely certain methodological limitations: the analyzed sample is relatively small; the cohorts were non-blinded; the study was performed in one center; and results were operator-dependent.

In conclusion, the results of our study strongly indicate that SF, as a novel and original method for collimation of X-rays, provides considerable lowering of the fluoroscopic dose and, in this way, a safer intervention for both patients and staff.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank graphic designer Håkan Pettersson and IT technician Mats Rynnes for their kind help with the quick preparation of all illustrations on the highest artistic level. They also thank Professor Elna-Marie Larsson for her strong support during the creation of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Söderman M, Mauti M, Boon S, et al. Radiation dose in neuroradiography using image noise reduction technology: a population study based on 614 patients. Neuroradiology 2013; 55: 1365–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein LW, Miller DL, Balter S, et al. Occupational health hazards in the interventional laboratory: Time for a safer environment. Radiology 2009; 250: 538–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dose-Area Product. Conference of Radiation Control Program Directors (CRCPD) 205 Capital Avenue Frankfort, KY 4060, First published: October 2001, Reviewed/Republished: September 2008. Available at: http://www.crcpd.org/Pubs/QAC/DAP.pdf.

- 4.Gallas S, Drouineau J, Gabrillargues J, et al. Feasibility, procedural morbidity and mortality, and long-term follow-up of endovascular treatment of 321 unruptured aneurysms. Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29: 63–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muroi T, Tanaka M, Shimizu Y, et al. Medical Diagnostic Imaging Apparatus. PCT/JP2013/052412. 2013.

- 6.Bednarek DR. Chapter: 25.1 Collimation. In: Karellas A and Thomadsen BR, eds. Cardiovascular and Neurovascular Imaging. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2016:427–429.

- 7.O’Dea TJ, Geise RA, Ritenour ER. The potential for radiation-induced skin damage in interventional neuroradiological procedures: a review of 522 cases using automated dosimetry. Medical Physics 1999; 26: 2027–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller DL, Balter S, Cole PE, et al. Radiation doses in interventional radiology procedures: the RAD-IR Study part i: overall measures of dose. J Vasc interv Radiol 2003; 14: 711–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Ercole L, Zappoli Thyrion F, Bocchiola M, et al. Proposed local reference levels in angiography and interventional neuroradiology and preliminary analysis according to the complexity of the procedures. Physica Medica 2012; 28: 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vano E, Fernandez JM, Sanchez RM, et al. Patient radiation dose management in the follow-up of potential skin injuries in neuroradiology. Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34: 277–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn EN, Gemmete JJ, Chaudhary N, et al. Radiation dose reduction during neurointerventional procedures by modification of default settings on biplane angiography equipment. J Neurointervent Surg 2016; 8: 819–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kemerink GJ, Franzen MJ, Oie K, et al. Patient and occupational dose in neurointerventional procedures. Neuroradiology 2002; 44: 522–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander MD, Oliff MC, Olorunsola OG, et al. Patient radiation exposure during diagnostic and therapeutic interventional procedures. J Neurointervent Surg 2010; 2: 6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urairat J, Asavaphatiboon S, Singhara NA, et al. Evaluation of radiation dose to patients undergoing interventional radiology procedures at Ramathibodi Hospital, Thailand. Biomed Imaging Interv J 2011; 7: e22–e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han SC, Kwon SC. Radiation dose reduction to the critical organ with bismuth shielding during endovascular coil embolization for cerebral aneurysms. Rad Protection Dosimetry 2013; 156: 364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Theodorakou CD, Patel J. A study on patient skin doses in cerebral embolisation using radiochromic films. Poster number C-0621, Congress ECR, Vienna, Austria, March 6-10 2014. Scientific exhibit. DOI: 10.1594/ecr2014/C-0621.