Abstract

The local control effect of esophagectomy with three-field lymph node dissection (3FLD) is reaching its limit pending technical advancement. Minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) by thoracotomy is slowly gaining acceptance due to advantages in short-term outcomes. Although the evidence is slowly increasing, MIE is still controversial. Also, the results of treatment by surgery alone are limiting, and multimodality therapy, which includes surgical and non-surgical treatment options including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and endoscopic treatment, has become the mainstream therapy. Esophagectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) is the standard treatment for clinical stages II/III (except for T4) esophageal cancer, whereas chemoradiotherapy (CRT) is regarded as the standard treatment for patients who wish to preserve their esophagus, those who refuse surgery, and those with inoperable disease. CRT is also usually selected for clinical stage IV esophageal cancer. On the other hand, with the spread of CRT, salvage esophagectomy has traditionally been recognized as a feasible option; however, many clinicians oppose the use of surgery due to the associated unfavorable morbidity and mortality profile. In the future, the improvement of each treatment result and the establishment of individual strategies are important although esophageal cancer has many treatment options.

Keywords: esophageal cancer treatment, current status

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the sixth leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide because of its high malignant potential and poor prognosis.1) Esophageal cancer is one of the worst malignant digestive neoplasms, and it also has a poor prognosis. The disease has evolved from predominantly squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) biologic characteristics to those of adenocarcinoma. Treatment strategies for esophageal malignancies can conceptually be divided along two axes: locoregional treatment and systemic therapy. Each patient should be individually assessed based on the type of cancer, local, or regional involvement, and his or her own functional status to determine an appropriate treatment regimen. Surgery continues to play an important role in achieving locoregional control in patients with esophageal carcinoma and offers the best chance for cure in localized and locally advanced disease. For nearly half a century, the mainstream treatment for esophageal cancer has been surgery although surgery with three-field lymph node dissection (3FLD) is a highly invasive procedure that can lead to severe complications and the possibility of mortality. Minimally invasive surgery, including thoracoscopic surgery for esophageal cancer, has been developed to reduce the physical burden. However, the superiority of video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS–esophagectomy) as compared with open esophagectomy (OE) is controversial. Despite improvement in surgical techniques and the advent of minimally invasive approaches, the majority of patients succumb to distant metastases after curative resection. Esophageal cancer has many treatment options because esophageal cancer’s sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiotherapy is higher as compared with other gastrointestinal cancers. Therefore, multimodal therapy, including surgical and non-surgical treatments, is selected from many of these options. A multidisciplinary team approach to management in a high-volume center is the preferred approach. Treatment strategies that combine the strengths of each treatment and that involve the close corporation of the treatment team, including paramedical staff, will resolve several problems and improve outcomes for esophageal cancer patients. Sato et al.2) reported that preoperative dental examination and care by a dentist are essential to reduce the likelihood of severe pneumonia postoperatively in esophageal cancer patients. Also, Cong et al.3) reported that a nutrition support team (NST) could provide significant positive effects in esophageal cancer patients during concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) and could be helpful in reducing the length of hospital stays. Recent advances in multimodality treatment show promise in improving outcomes and survival while decreasing morbidity; however, they are still far from sufficient. The proper staging workup is vital to determine treatment strategies and goals. Once determined, a multidisciplinary approach should be employed for treatment and surveillance. Normally, evaluation results and treatment options for each patient with localized esophageal cancer should be discussed in a multidisciplinary treatment planning conference.

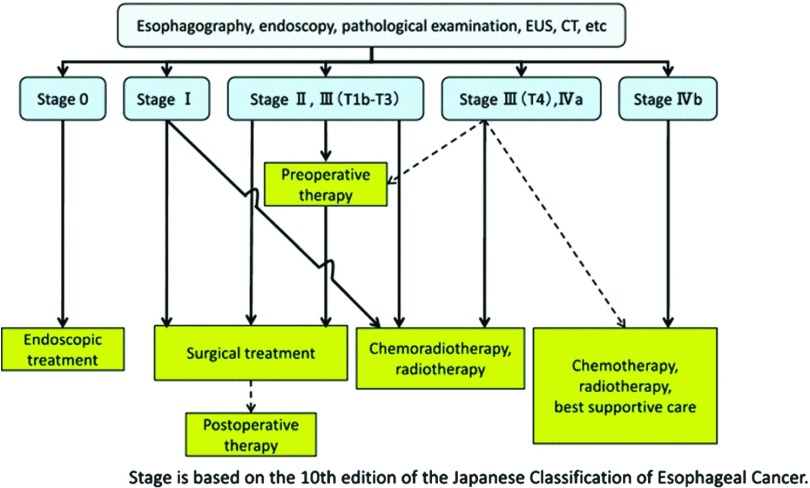

In Japan, the Japan Esophageal Society has prepared systematic diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines.4) A therapeutic algorithm is shown in these guidelines (Fig. 1).4) According to this therapeutic algorithm, endoscopic therapy is recommended for mucosal cancer, whereas surgery is recommended for more invasive tumors if the tumor has resectability. For tumors that invade the muscularis propria or adventitia and/or with lymph node (LN) metastases, adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapies are combined. If the tumor has invaded an adjacent organ or if there are distant metastases, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and CRT are therapeutic options. For submucosal cancer without metastasis, CRT is selected as the definitive therapy in some cases. Moreover, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) is performed for resectable tumors as a result of the JCOG9907 study.5) Esophageal cancer treatment is difficult and should be chosen carefully because it is cumbersome and complicated, as indicated above. In this article, we review the current status and future prospects for the treatment of esophageal cancer, especially for SCC.

Fig. 1. A therapeutic algorithm for esophageal cancer from the Guideline for Diagnostic and Treatment of carcinoma of the Esophagus (April 2012 edition). CT: computed tomography; EUS: endoscopic ultrasonography.

Endoscopic Treatment

Two established methods aim to cure mucosal cancers: endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).6) Among lesions that do not exceed the mucosal layer (T1a), those remaining within the mucosal epithelium (EP) or the lamina propria mucosae (LPM) are extremely rarely associated with LN metastasis; therefore, endoscopic resection is a sufficiently radical treatment for these lesions.4) ESD was developed as a new endoscopic treatment in which the affected mucosa is incised and removed using a variety of endoscopic knives. The major advantages of ESD include both an extremely high rate of en bloc resection and the possibility of resection for lesions with submucosal fibrosis.7,8) Takahashi et al.9) compared the clinical outcomes of EMR and ESD groups; they also showed that the mean excision time was significantly longer for the ESD procedure than for the EMR procedure. However, the en bloc resection rate and the Cur A rate were significantly higher in the ESD group.9) Cumulative disease-free survival (DFS) was significantly better with ESD; however, overall survival (OS) was similar for both procedures.9) A recent meta-analysis from Korea showed ESD to be significantly more effective than EMR for en bloc resection, complete resection, curative resection, and local recurrence. Although a systematic review and meta-analysis of early gastric cancer showed that intraoperative bleeding, perforation risk, and operation times were significantly greater for ESD, the overall bleeding risk and all-cause mortality with ESD or EMR did not differ significantly.10) With regard to early esophageal carcinoma, meta-analysis of ESD did not show increased incidence of procedure-related complications as compared with EMR.11)

The limitation of circumference disappeared because of improvement of the technique and stenosis prevention in the guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of carcinoma of the esophagus edited by the Japan Esophageal Society in April 2012.4) Subcircumferential or circumferential ESD was performed in the clinical setting in patients who were hoped would not have to undergo esophagectomy or patients with severe comorbidities.12,13) Thereafter, most of these patients required several sessions of dilation because of severe/refractory dysphasia although their preoperative conditions were asymptomatic. Repeated dilation has the potential risk of tears/perforation, which results in potentially lethal complications and worsens the quality of life (QOL).11,14) The current study showed that tumor size and whole circumference resection were independent risk factors for stricture after ESD.15) Therefore, provision for stricture after ESD is subject for future study. Yamaguchi et al.16) reported the efficacy of systemic steroid therapy using oral prednisolone for stricture prevention. They reported that patients in the systemic steroid therapy group had a significantly lower rate of stenosis as compared with those in the preventive endoscopic balloon dilation (EBD) group. Sato et al.17) also reported that the administration of systemic steroid therapy concomitant with therapeutic EBD was more effective than therapeutic EBD alone in the prevention of esophageal strictures after circumferential ESD. They concluded that oral steroid therapy after EBD is an effective strategy for the management of esophageal strictures after complete circumferential ESD. The local injection of triamcinolone acetonide18) and other systemic steroid therapies13) are frequently used to prevent esophageal strictures after ESD. Moreover, ESD for esophageal cancer is generally a more difficult technique as compared to ESD for gastric cancer because the working space is small in esophageal ESD. Additionally, the level of difficulty gradually increases depending on the area of carcinoma. To overcome these difficulties, the double endoscopic intraluminal operation (DEILO), which enables us to resect mucosal lesions using two fine endoscopes and monopolar shears, was reported by our institute in 2004.19) DEILO is very utilitarian method of ESD for early esophageal cancers. Additional improvements and advancements of the device will lead to broader usage of DEILO.

Surgical Treatment

Due to improvements in the surgical procedure and perioperative management, surgical performance has greatly improved in recent years. Given the frequency and extent of LN metastasis and its significance for survival, controlling LN metastasis is a rational therapeutic strategy; therefore, extended LN dissection, such as 3FLD, may be logical although appropriate patient selection is necessary. Many previous reports have shown the superiority of 3FLD as compared with two-field LN dissection (2FLD).20–27) The discussion regarding the extent of LN dissection has mainly centered on thoracic esophageal SCC in Japan.

Nishihira et al.25) reported the superiority of 3FLD. As reported in their articles, 5-year survival was better after 3FLD (64.8%) than 2FLD (48.0%). Udagawa et al.26) also showed that cervical LN dissection had a high efficiency index for upper and middle thoracic esophageal cancer. Kato et al.27) also showed that 3FLD had a significantly smaller recurrence rate as compared with 2FLD (10% and 19%, respectively). Ye et al.28) also indicated that 3FLD could be a priority for thoracic esophageal cancer, especially for tumors with positive LNs although in 13 published studies,28) 3FLD caused increased anastomotic leakage as compared with 2FLD. Esophagectomy with 3FLD appears to be acceptable and may improve the prognosis of patients. However, 3FLD is not always considered a standard procedure in Western countries.29) No report concretely proves the difference in lymphadenectomies among these carcinomas; however, the extent of LN dissection may be different because SCC is mostly located in the thoracic area, whereas adenocarcinoma is more often located in the GEJ area. Recently, there has been much discussion regarding the extent of LN dissection in adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction although the discussion regarding the extent of LN dissection has been mainly centered on thoracic esophageal SCC in Japan. The minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE), laparoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy (THE), was also advocated by DePaula et al.30) in 1995. Based on a systematic review of the literature, Parry et al.31) reported that laparoscopic THE was demonstrated to be safe and feasible with evidence of reduced blood loss and shorter hospital stays as compared with open THE.

Esophagogastric junction (EGJ) carcinoma, which represents carcinoma involving the anatomical border between the esophagus and the stomach, has attracted considerable attention recently because of its marked increase. There has been controversy regarding the best surgical method for carcinoma of the EGJ. A meta-analysis comparison of transthoracic and abdominal transhiatal resection for the treatment of Siewert types II/III adenocarcinomas of the EGJ has been completed.32) Based on this study, the transthoracic approach was associated with a longer hospital stay and had higher incidences of respiratory and cardiovascular complications and early postoperative mortality as compared with the abdominal transhiatal approach. There were no significant differences between the two approaches related to long-term survival. At present, there is no worldwide consensus regarding the optimal extent of LN dissection. There has been no systematic randomized control trial to examine the superiority of 3FLD. Given the lack of large-sample randomized controlled studies, further evaluation is necessary.

On the other hand, VATS and radical esophagectomy have been developed to reduce surgical invasion in the management of esophageal cancer.33–35) A multicenter open-label randomized control trial compared MIE and OE for patients with esophageal cancer showed that MIE resulted in a lower incidence of pulmonary infections 2 weeks after surgery and during stay in the hospital, a shorter hospital stay, and better short-term QOL than did OE.35)

In Japan, Akaishi et al.36) first reported in 1996 the feasibility of the thoracoscopic technique as compared to the open technique for esophagectomy. Furthermore, certain retrospective studies have shown that the oncological effectiveness of thoracoscopic surgery is comparable to that of open thoracotomy.37–39) Thomson et al.38) reported that VATS–esophagectomy provides adequate locoregional control of VATS–esophagectomy comparable to that of open surgery. Also, a comparative study of the prone position (PP) versus the lateral decubitus position (LDP) for VATS–esophagectomy reported that the estimated median intraoperative blood loss was significantly less in the PP group as compared with the LDP group, and the PP group experienced fewer respiratory complications than did the LDP group.40)

In recent years, a comparative study of MIE versus OE outcomes using the National Clinical Database (NCD) in Japan has been reported.41) The operative time was significantly longer in the MIE group than in the OE group, whereas blood loss was markedly reduced in the MIE group as compared to the OE group. Also, the incidence of anastomotic leakage was significantly higher in the MIE group than in the OE group. Moreover, the rate of reoperation within 30 days was significantly higher in the MIE group than in the OE group.41) The superiority of VATS–esophagectomy over OE is controversial. Further randomized control studies will be necessary in the future.

Esophagectomy is the key element in the curative treatment of patients with esophageal cancer. However, the type of approach and the extent of lymphadenectomy that is necessary for esophageal cancer patients remain disputed.

Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Chemotherapy

Surgical resection has constituted the main treatment option in the management of esophageal cancer. Despite advances in surgical methodologies, long-term survival after surgery alone for advanced esophageal cancer has remained poor. The implementation of perioperative chemotherapy has improved survival rates. The theoretical advantages of adding chemotherapy to the treatment of esophageal cancer are potential tumor downstaging prior to surgery as well as targeting micrometastases, thus decreasing the risk of distant metastasis.42) On the other hand, the potential disadvantages include the morbidity and mortality associated with toxicity, disease progression with the selection of drug-resistant tumor clones, and the delay of definitive surgical treatment.42)

In Japan, JCOG9204, a phase III trial performed by Ando et al. to compare survival with surgery alone with that of surgery plus postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with two courses of cisplatin and fluorouracil (FP) in patients with resected esophageal SCC, concluded that there was a significant benefit in 5-year DFS from postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with FP in the group of patients with positive LNs.43) Lee et al.44) and Zhang et al.45) also reported similar results. Recently, Rong et al.46) also reported that the group given adjuvant chemotherapy with docetaxel- or paclitaxel-based regimens had a significantly longer median DFS than that in the surgery alone group but resulted in no significant difference in OS between these groups. The effects of preoperative chemotherapy are being evaluated in randomized trials. Several studies have demonstrated a survival benefit with surgery alone.5,47,48) JCOG9907, which compared survival with postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with FP and that of preoperative chemotherapy for localized advanced SCC of the thoracic esophagus, showed that preoperative chemotherapy offered significantly superior OS.5) However, there was no significant difference between groups with respect to progression-free survival. Additionally, there was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to postoperative complications or treatment-related toxicities.5) With regard to the influence of NAC using a CF regimen for esophageal SCC, Hirao et al.49) concluded that preoperative chemotherapy does not increase the risk of complications or hospital mortality after surgery for advanced thoracic esophageal cancer. However, one large randomized study failed to confirm a survival benefit with preoperative chemotherapy.50) Additionally, Matsuda et al.51) reported that no significant difference in OS was observed between NAC and upfront surgery in clinical stage III esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) patients. Although preoperative chemotherapy with FP is the standard therapy for clinical stages II/III thoracic esophageal cancer, further investigation is needed before changing the regimen.

Recently, the efficacy of combined chemotherapy using docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5FU (DCF) for esophageal cancer has been reported.52–57) Nomura et al.56) reported that the overall response rate was significantly higher in the DCF group than in the CF group in patients with clinical stage III or T3 esophageal SCC. After propensity score matching, the improvement in OS in the DCF group reached statistical significance (p = 0.05). Watanabe et al.54) also concluded that DCF has strong antitumor activity for esophageal cancer and may confer survival benefits when used as preoperative chemotherapy in patients with resectable node-positive esophageal cancer. Moreover, Ojima et al.57) reported that NAC with divided-dose DCF led to a high frequency of pathological responses among patients with advanced esophageal SCC. Sudarshan et al.55) reported favorable oncologic outcomes with low local/regional recurrence and an excellent overall 5-year survival after neoadjuvant DCF for esophageal and locally advanced esophagogastric adenocarcinoma. With regard to adverse events, patients in the preoperative DCF group had a high incidence of hematologic toxicity, particularly neutropenia and febrile neutropenia, as compared with patients in the preoperative CF group although the incidence of non-hematologic toxicity did not differ significantly between the two groups.53)

Moreover, Tanaka et al.58) reported a phase II trial of NAC with docetaxel, nedaplatin, and S1 for advanced esophageal SCC; they showed that this regimen was well tolerated and highly active.

Neoadjuvant CRT

For SCC, a multicenter prospective randomized trial that compared preoperative combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy versus surgery alone in stages I and II patients with SCC was reported in 1997.59) In that report, preoperative CRT did not improve OS; however, it did prolong DFS and survival free of local disease. Nevertheless, in this report, preoperative CRT also showed significantly higher postoperative mortality than did surgery alone. Additionally, the ChemoRadiotherapy for Oesophageal cancer followed by Surgery Study (CROSS) has definitively demonstrated a survival benefit for preoperative chemoradiation as compared with surgery alone in resectable esophageal cancer.60) Preoperative CRT improved survival among patients with potentially curable esophageal or esophagogastric-junction cancer and improved the rate of complete resection with no tumor within 1 mm of the resection margins (R0). Analysis of subgroups in the CROSS trial shows that neoadjuvant CRT improves survival for patients with SCC60) although most patients enrolled in the CROSS trial (75%) had adenocarcinoma. Moreover, as a result of updated meta-analysis, Sjoquist et al.61) reported that neoadjuvant CRT following surgery shows strong evidence of a survival benefit as compared with surgery alone in patients with esophageal SCC.

On the other hand, two recent studies62,63) directly compared survival after preoperative chemotherapy and preoperative CRT for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Although a trend toward improved survival was observed after CRT, there was no significant difference in survival between the two arms in either of the clinical studies. Preoperative CRT was associated with better complete pathological rates as compared with the chemotherapy arm. Preoperative CRT did not show significant superiority for SCC; further randomized investigations will be needed in the future. Fan et al.64) also used meta-analysis to report on survival after NAC versus neoadjuvant CRT for resectable esophageal carcinoma. In their report, they showed that induction CRT improved the OS of esophageal cancer patients as compared with induction CT alone and that the pathological complete response rate was higher in the induction CRT group. However, perioperative mortality and the postoperative complication rate were higher in the neoadjuvant CRT group. Yokota et al.65) compared the efficacy of DCF with that of cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil (FP) as induction chemotherapy for locally advanced borderline-resectable esophageal cancer. They concluded that DCF induction chemotherapy may be an option for conversion therapy of initially unresectable locally advanced esophageal cancer.

Definitive CRT

CRT is the standard therapy for unresectable esophageal cancer and is also considered as an option for resectable cancer. Additionally, definitive CRT may also be performed for patients who refuse or who cannot tolerate surgery. For patients who are medically or technically inoperable, concurrent CRT should be the standard of care. The most commonly applied regimen for radiosensitization in esophageal cancer is the doublet combination of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (FP). However, the outcome of this regimen remains unsatisfactory in terms of local control, toxicity, and OS benefit.66–68) Therefore, more effective regimens must be investigated to improve the prognosis of patients with locally advanced esophageal cancer. We previously reported a phase I/II study of docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil combination chemoradiotherapy (DCF-RT) in patients with advanced esophageal cancer.69) DCF-RT ensures safety and feasibility by adequately managing myelotoxicity in recommended dose. As a result, we have concluded that this protocol might produce a high CR rate and a favorable prognosis as compared with standard CRT for advanced esophageal cancer. However, this study is limited by the small number of patients that were included. Further validation studies are needed. Recently, Nomura et al.70) compared survival with NAC followed by surgery (S group) with that with definitive CRT (CRT group) for patients with potentially resectable esophageal SCC. They showed that progression-free and OSs were better in the S group than in the CRT group. Moreover, both survival outcomes were better in the S group for patients with only stage III disease although survival outcomes for stages I, II, and IV were not significantly different.

Salvage Esophagectomy

JCOG9906, reported by Kato et al.,71) showed that CRT is effective for stages II and III ESCC with manageable acute toxicities and can provide a non-surgical treatment option. In their report, they showed that the median survival time was 29 months, with 3- and 5-year survival rates of 44.7% and 36.8%, respectively. Although this survival data are inferior as compared to that of standard NAC following surgery, this option is very important from the perspective of preserving the function of the esophagus. However, remnant tumors or recurrences are practical problems that require salvage esophagectomy. Salvage ESD is recommended if target lesions are diagnosed as intramucosal or submucosal tumors without metastases.72) Salvage surgery is needed if the tumor has invaded a deeper layer. According to the therapeutic guidelines,4) the indication for salvage surgery was decided by evaluating tumors and patients’ individual factors. Currently, no treatment other than salvage surgery is accepted as a curative treatment for residual or recurrent tumors. In many cases, it is difficult to judge whether there is a possibility of curative resection, in spite of the many diagnostic images taken. Moreover, predicting long-term survival for these patients is also difficult. Although the window of opportunity for curative treatment is very narrow, salvage esophagectomy has traditionally been recognized as a feasible option; however, many clinicians oppose the use of surgery due to the associated unfavorable morbidity and mortality profile. Many previous reports of salvage esophagectomy have showed higher postoperative morbidity and mortality rates in hospital stays.73–75) Tachimori et al.75) recommended technical artifice for the preservation of tracheal necrosis, right tracheal artery preservation, and the omission of cervical lymphadenectomy to preserve the inferior thyroid artery. They also discussed changing the posterior mediastinal route to the retrosternal route for salvage esophagectomy.

Recently, Yoo et al.76) reported that there were no in-hospital deaths (0%) after esophagectomy, and Chao et al.77) reported that the hospital mortality rate after esophagectomy was 2.0%. These recent statistics are obviously lower than those of a previous study,74) suggesting that advances in surgical techniques and perioperative intensive care are improving the postoperative outcome after salvage esophagectomy although the backgrounds of these report are not completely identical. With regard to comparing salvage esophagectomy with second-line CRT without surgery for recurrent or persistent SCC after definitive CRT. Kumagai et al.78) reported that salvage esophagectomy offers significant gains in long-term survival as compared with second-line CRT although the surgery has the potential price of high-treatment-related mortality. Presently, a non-randomized validation study for definitive CRT with or without salvage esophagectomy is being implemented in stages II/III (excluding T4) (JCOG0909). The results of this study will influence the future treatment of recurrent or persistent esophageal cancer.

Future Prospects of Esophageal Cancer Treatment

Treatment modalities for esophageal SCC have become subdivided according to the clinical stage. For early-stage esophageal SCC, adequate results have been obtained with several treatments. Endoscopic submucosal resection is an excellent procedure for treating early-stage esophageal SCC. In accordance with improved ESD techniques, subcircumferential or circumferential ESD was performed clinically. Adequate stenosis prevention will need to avoid decreasing the QOL. However, there is no specified method for stenosis prevention, whether steroid injection, oral administration, or both, adequate intervals, or periods of balloon dilation. Moreover, to detect esophageal cancer early, additional high-quality, accurate diagnostic devices must be developed. Resolving these problems will lead to the stable treatment of early esophageal cancer.

With regard to surgery, several approaches for resection have been described: transthoracic, transhiatal, abdominothoracic, and, most recently, minimally invasive resection. The MIE approach using thoracoscopy in the prone or lateral position or by the transhiatal approach is being widely implemented and increasingly performed all over the world for patients with resectable esophageal cancer to reduce postoperative respiratory complications and to enhance the QOL by avoiding thoracic and abdominal wall destruction. However, several problems are presented in the standardization of VATS–esophagectomy. VATS–esophagectomy has no obvious merit over standard OE although it is less invasive surgery which leads to fewer postoperative respiratory complications or bleeding during surgery. The superiority of VATS–esophagectomy over OE is unsettled. In the near future, increasing numbers of patients will demonstrate the superiority of the VATS–esophagectomy. Gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma is increasing in Japan. However, there is no apparent evidenced procedure, including operating position (supine or lateral), by thoracotomy or transhiatal approach, and extension of lymphadenectomy. In recent years, the usefulness and feasibility of robotic transthoracic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer have been reported.79,80) Sluis et al.80) reported that robot-assisted minimally invasive thoraco-laparoscopic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer has good local control with a low percentage of local recurrence on long-term follow-up. With regard to robot-assisted esophagectomy, the further accumulation of patients or a randomized control study will be needed before worldwide adoption. Robot-assisted esophagectomy will be an ideal operation in the future, with the double benefits of resectability and safety. With regard to chemotherapy, the outcome of the FP regimen remains unsatisfactory in terms of local control, toxicity, and OS benefit; more effective regimens must be investigated to improve the prognosis of patients with locally advanced esophageal cancer. DCF therapy is a promising candidate because some reports have shown excellent local control and pathological remission rates. However, problems with this regimen include a high incidence of hematological adverse events, including febrile neutropenia, appetite loss, diarrhea/constipation, and general fatigue.81,82) The resolution of these adverse events and the further development of an effective regimen will improve the survival of esophageal cancer patients.

Molecular Target Therapy

Bonner et al.83) reported that radiotherapy plus cetuximab significantly improves OS at 5 years as compared with radiotherapy alone for patients with locoregionally advanced head and neck cancers. The usefulness of this perioperative use of cetuximab for esophageal cancer is expected because its pathological feature is similar to that of head and neck cancer (major pathological-type SCC).

Crosby et al.84) investigated the effect of cetuximab in addition to FP based on definitive CRT in patients with localized esophageal squamous cell cancer and adenocarcinomas. However, the CRT plus cetuximab group had shorter median OS, lower compliance with treatment, and higher toxicity as compared with the CRT group. As a result, the addition of cetuximab to standard chemotherapy and radiotherapy cannot be recommended for patients with esophageal cancer suitable for definitive CRT. Moreover, Dutton85) reported that the usefulness of gefitinib as a second-line treatment in esophageal cancer in unselected patients does not improve OS but has palliative benefits in a subgroup of difficult-to-treat patients with short life expectancies. Additionally, Xu et al.86) reported on preliminary results of a phase II study regarding the efficacy of gefitinib combined with radiation in small patients with esophageal SCC. There is no useful and proven molecular target therapy for esophageal cancer at the present moment. Also, there is insufficient data dealing only with SCC although it is the most common pathological type in Japan. The further development of molecular target therapy, especially for SCC, and an effective combination regimen of chemotherapy will lead to improvement for esophageal cancer patients. Additionally, to investigate the most effective preoperative therapy, a three-arm phase III trial comparing FP versus DCF versus radiotherapy with FP-RT as preoperative therapy for locally advanced esophageal cancer (JCOG1109, NExT study) is currently ongoing in Japan.84) The results of this study will bring a new dimension to preoperative chemotherapy for esophageal cancer. Recently, individualization treatment was emphasized in cancer treatment. In esophageal cancer, patients who respond to pretreatment therapy have better prognoses than those who do not respond. Unnecessary treatment, toxicity, and long treatment times will be avoided if positive responders in the preoperative period are accurately selected, and it can also provide rational evidence for the need of radical surgery early. With regard to definitive CRT, pretreatment for the accurate selection of responders will eliminate remnant and recurrence cases and can indicate the need for rational radical surgery for non-responder esophageal cancer patients. Additionally, investigative studies of potential molecular target therapies, including anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor drugs, will lead to new therapeutic options for multimodality therapy.

The current treatment of esophageal cancer involves multidisciplinary therapies, including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and endoscopic treatment. Multidisciplinary therapies have been developed to prolong the survival of patients with esophageal cancer. Treatment strategies that combine the strengths of each treatment and that involve the close corporation of the treatment team, including paramedical staff, will resolve several problems and improve outcomes for esophageal cancer patients. Moreover, additional improvement in therapeutic outcomes will be more important for individual treatment in the future.

Disclosure Statement

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest and have received no payment in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1).Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011; 61: 69-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Sato Y, Motoyama S, Takano H, et al. Esophageal Cancer Patients Have a High Incidence of Severe Periodontitis and Preoperative Dental Care Reduces the Likelihood of Severe Pneumonia after Esophagectomy. Dig Surg 2016; 33: 495-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Cong MH, Li SL, Cheng GW, et al. An Interdisciplinary Nutrition Support Team Improves Clinical and Hospitalized Outcomes of Esophageal Cancer Patients with Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy. Chin Med J 2015; 128: 3003-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Kuwano H, Nishimura Y, Oyama T, et al. Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Carcinoma of the Esophagus April 2012 edited by the Japan Esophageal Society. Esophagus 2015; 12: 1-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Ando N, Kato H, Igaki H, et al. A randomized trial comparing postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil versus preoperative chemotherapy for localized advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus (JCOG9907). Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19: 68-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Wang KK, Prasad G, Tian J. Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection in esophageal and gastric cancers. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2010; 26: 453-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Oyama T, Tomori A, Hotta K, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early esophageal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 3: S67-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kakushima N, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of esophageal squamous cell neoplasms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4: 688-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Takahashi H, Arimura Y, Masao H, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection is superior to conventional endoscopic resection as a curative treatment for early squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72: 255-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Park YM, Cho E, Kang HY, et al. The effectiveness and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Surg Endosc 2011; 25: 2666-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Wang J, Ge J, Zhang XH, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection for the treatment of early esophageal carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014; 15: 1803-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Fujishiro M. Perspective on the practical indications of endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastrointestinal neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 4289-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Isomoto H, Yamaguchi N, Nakayama T, et al. Management of esophageal stricture after complete circular endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol 2011; 11: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Zuercher BF, George M, Escher A, et al. Stricture prevention after extended circumferential endoscopic mucosal resection by injecting autologous keratinocytes in the sheep esophagus. Surg Endosc 2013; 27: 1022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Funakawa K, Uto H, Sasaki F, et al. Effect of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal neoplasms and risk factors for postoperative stricture. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015; 94: e373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Yamaguchi N, Isomoto H, Nakayama T, et al. Usefulness of oral prednisolone in the treatment of esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 73: 1115-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Sato H, Inoue H, Kobayashi Y, et al. Control of severe strictures after circumferential endoscopic submucosal dissection for esophageal carcinoma: oral steroid therapy with balloon dilation or balloon dilation alone. Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 78: 250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Takahashi H, Arimura Y, Okahara S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of endoscopic steroid injection for prophylaxis of esophageal stenoses after extensive endoscopic submucosal dissection. BMC Gastroenterol 2015; 15: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Kuwano H, Mochiki E, Asao T, et al. Double endoscopic intraluminal operation for upper digestive tract diseases: proposal of a novel procedure. Ann Surg 2004; 239: 22-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Akiyama H, Tsurumaru M, Udagawa H, et al. Radical lymph node dissection for cancer of the thoracic esophagus. Ann Surg 1994; 220: 364-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Isono K, Sato H, Nakayama K. Results of a nationwide study on the three-field lymph node dissection of esophageal cancer. Oncology 1991; 48: 411-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Lerut T, Coosemans W, De Leyn P, et al. Reflections on three field lymphadenectomy in carcinoma of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. Hepatogastroenterology 1999; 46: 717-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Baba M, Aikou T, Yoshinaka H, et al. Long-term results of subtotal esophagectomy with three-field lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. Ann Surg 1994; 219: 310-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Tachibana M, Kinugasa S, Yoshimura H, et al. Clinical outcomes of extended esophagectomy with three-field lymph node dissection for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Surg 2005; 189: 98-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Nishihira T, Hirayama K, Mori S. A prospective randomized trial of extended cervical and superior mediastinal lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. Am J Surg 1998; 175: 47-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Udagawa H, Ueno M, Shinohara H, et al. The importance of grouping of lymph node stations and rationale of three-field lymphoadenectomy for thoracic esophageal cancer. J Surg Oncol 2012; 106: 742-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Kato H, Tachimori Y, Watanabe H, et al. Recurrent esophageal carcinoma after esophagectomy with three-field lymph node dissection. J Surg Oncol 1996; 61: 267-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Ye T, Sun Y, Zhang Y, et al. Three-field or two-field resection for thoracic esophageal cancer: a meta- analysis. Ann Thorac Surg 2013; 96: 1933-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Grotenhuis BA, van Heijl M, Zehetner J, et al. Surgical management of submucosal esophageal cancer: extended or regional lymphadenectomy? Ann Surg 2010; 252: 823-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).DePaula AL, Hashiba K, Ferreira EA, et al. Laparoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy with esophagogastroplasty. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1995; 5: 1-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Parry K, Ruurda JP, van der Sluis PC, et al. Current status of laparoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy for esophageal cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. Dis Esophagus 2016. February 26 doi: 10.1111/dote.12477. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Zheng Z, Cai J, Yin J, et al. Transthoracic versus abdominal-transhiatal resection for treating Siewert type II/III adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8: 17167-82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Cuschieri A, Shimi S, Banting S. Endoscopic oesophagectomy through a right thoracoscopic approach. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1992; 37: 7-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Nagpal K, Ahmed K, Vats A, et al. Is minimally invasive surgery beneficial in the management of esophageal cancer? A meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 2010; 24: 1621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Biere SS, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Maas KW, et al. Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 379: 1887-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Akaishi T, Kaneda I, Higuchi N, et al. Thoracoscopic en bloc total esophagectomy with radical mediastinal lymphadenectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996; 112: 1533-40; discussion 1540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Osugi H, Takemura M, Higashino M, et al. A comparison of video-assisted thoracoscopic oesophagectomy and radical lymph node dissection for squamous cell cancer of the oesophagus with open operation. Br J Surg 2003; 90: 108-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Thomson IG, Smithers BM, Gotley DC, et al. Thoracoscopic-assisted esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: analysis of patterns and prognostic factors for recurrence. Ann Surg 2010; 252: 281-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Kinjo Y, Kurita N, Nakamura F, et al. Effectiveness of combined thoracoscopic-laparoscopic esophagectomy: comparison of postoperative complications and midterm oncological outcomes in patients with esophageal cancer. Surg Endosc 2012; 26: 381-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Javed A, Manipadam JM, Jain A, et al. Minimally invasive oesophagectomy in prone versus lateral decubitus position: A comparative study. J Minim Access Surg 2016; 12: 10-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41).Takeuchi H, Miyata H, Gotoh M, et al. A risk model for esophagectomy using data of 5354 patients included in a Japanese nationwide web-based database. Ann Surg 2014; 260: 259-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42).Kato H, Nakajima M. Treatments for esophageal cancer: a review. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013; 61: 330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43).Ando N, Iizuka T, Ide H, et al. Surgery plus chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for localized squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus: a Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study—JCOG9204. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 4592-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44).Lee J, Lee KE, Im YH, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin in lymph node-positive thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2005; 80: 1170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45).Zhang SS, Yang H, Xie X, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy versus surgery alone for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and nonrandomized studies. Dis Esophagus 2014; 27: 574-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46).Qin RQ, Wen YS, Wang WP, et al. The role of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for lymph node-positive esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a propensity score matching analysis. Med Oncol 2016; 33: 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47).Medical Research Council Oesophageal Cancer Working Group Surgical resection with or without preoperative chemotherapy in oesophageal cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 359: 1727-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48).Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon JP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 1715-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49).Hirao M, Ando N, Tsujinaka T, et al. Influence of preoperative chemotherapy for advanced thoracic oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma on perioperative complications. Br J Surg 2011; 98: 1735-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50).Kelsen DP, Ginsberg R, Pajak TF, et al. Chemotherapy followed by surgery compared with surgery alone for localized esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 1979-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51).Matsuda S, Tsubosa Y, Sato H, et al. Comparison of neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus upfront surgery with or without chemotherapy for patients with clinical stage III esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dis Esophagus 2016. February 26 doi: 10.1111/dote.12473. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52).Hara H, Tahara M, Daiko H, et al. Phase II feasibility study of preoperative chemotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci 2013; 104: 1455-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53).Ui T, Fujii H, Hosoya Y, et al. Comparison of preoperative chemotherapy using docetaxel, cisplatin and fluorouracil with cisplatin and fluorouracil in patients with advanced carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. Dis Esophagus 2015; 28: 180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54).Watanabe M, Baba Y, Yoshida N, et al. Outcomes of preoperative chemotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil followed by esophagectomy in patients with resectable node-positive esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2014; 21: 2838-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55).Sudarshan M, Alcindor T, Ades S, et al. Survival and recurrence patterns after neoadjuvant docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (DCF) for locally advanced esophagogastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22: 324-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56).Nomura M, Oze I, Abe T, et al. Impact of docetaxel in addition to cisplatin and fluorouracil as neoadjuvant treatment for resectable stage III or T3 esophageal cancer: a propensity score-matched analysis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2015; 76: 357-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57).Ojima T, Nakamori M, Nakamura M, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy with Divided-dose Docetaxel, Cisplatin and Fluorouracil for Patients with Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Esophagus. Anticancer Res 2016; 36: 829-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58).Tanaka Y, Yoshida K, Tanahashi T, et al. Phase II trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with docetaxel, nedaplatin, and S1 for advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci 2016; 107: 764-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59).Bosset JF, Gignoux M, Triboulet JP, et al. Chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery compared with surgery alone in squamous-cell cancer of the esophagus. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60).van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 2074-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61).Sjoquist KM, Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, et al. Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal carcinoma: an updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12: 681-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62).Stahl M, Walz MK, Stuschke M, et al. Phase III comparison of preoperative chemotherapy compared with chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 851-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63).Burmeister BH, Thomas JM, Burmeister EA, et al. Is concurrent radiation therapy required in patients receiving preoperative chemotherapy for adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus? A randomised phase II trial. Eur J Cancer 2011; 47: 354-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64).Fan M, Lin Y, Pan J, et al. Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for resectable esophageal carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Thorac Cancer 2016; 7: 173-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65).Yokota T, Hatooka S, Ura T, et al. Docetaxel plus 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin (DCF) induction chemotherapy for locally advanced borderline-resectable T4 esophageal cancer. Anticancer Res 2011; 31: 3535-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66).Cooper JS, Guo MD, Herskovic A, et al. Chemoradiotherapy of locally advanced esophageal cancer: long-term follow-up of a prospective randomized trial (RTOG 85-01). Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. JAMA 1999; 281: 1623-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67).Ishida K, Ando N, Yamamoto S, et al. Phase II study of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil with concurrent radiotherapy in advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: a Japan Esophageal Oncology Group (JEOG)/Japan Clinical Oncology Group trial (JCOG9516). Jpn J Clin Oncol 2004; 34: 615-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68).Ohtsu A, Boku N, Muro K, et al. Definitive chemoradiotherapy for T4 and/or M1 lymph node squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 2915-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69).Miyazaki T, Sohda M, Tanaka N, et al. Phase I/II study of docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil combination chemoradiotherapy in patients with advanced esophageal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2015; 75: 449-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70).Nomura M, Oze I, Kodaira T, et al. Comparison between surgery and definitive chemoradiotherapy for patients with resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a propensity score analysis. Int J Clin Oncol 2016; 21: 890-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71).Kato K, Muro K, Minashi K, et al. Phase II study of chemoradiotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin for Stage II-III esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: JCOG trial (JCOG 9906). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011; 81: 684-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72).Takeuchi M, Kobayashi M, Hashimoto S, et al. Salvage endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with local failure after chemoradiotherapy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Scand J Gastroenterol 2013; 48: 1095-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73).Nishimura M, Daiko H, Yoshida J, et al. Salvage esophagectomy following definitive chemoradiotherapy. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007; 55: 461-4; discussion 464-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74).Miyata H, Yamasaki M, Takiguchi S, et al. Salvage esophagectomy after definitive chemoradiotherapy for thoracic esophageal cancer. J Surg Oncol 2009; 100: 442-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75).Tachimori Y, Kanamori N, Uemura N, et al. Salvage esophagectomy after high-dose chemoradiotherapy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009; 137: 49-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76).Yoo C, Park JH, Yoon DH, et al. Salvage esophagectomy for locoregional failure after chemoradiotherapy in patients with advanced esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2012; 94: 1862-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77).Chao YK, Chan SC, Chang HK, et al. Salvage surgery after failed chemoradiotherapy in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Eur J Surg Oncol 2009; 35: 289-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78).Kumagai K, Mariosa D, Tsai JA, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the significance of salvage esophagectomy for persistent or recurrent esophageal squamous cell carcinoma after definitive chemoradiotherapy. Dis Esophagus 2016; 29: 734-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79).Puntambekar S, Kenawadekar R, Kumar S, et al. Robotic transthoracic esophagectomy. BMC Surg 2015; 15: 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80).van der Sluis PC, Ruurda JP, Verhage RJ, et al. Oncologic Long-Term Results of Robot-Assisted Minimally Invasive Thoraco-Laparoscopic Esophagectomy with Two-Field Lymphadenectomy for Esophageal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22: S1350-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81).Emi M, Hihara J, Hamai Y, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil for esophageal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2012; 69: 1499-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82).Higuchi K, Koizumi W, Tanabe S, et al. A phase I trial of definitive chemoradiotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (DCF-R) for advanced esophageal carcinoma: Kitasato digestive disease & oncology group trial (KDOG 0501). Radiother Oncol 2008; 87: 398-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83).Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer: 5-year survival data from a phase 3 randomised trial, and relation between cetuximab- induced rash and survival. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 21-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84).Crosby T, Hurt CN, Falk S, et al. Chemoradiotherapy with or without cetuximab in patients with oesophageal cancer (SCOPE1): a multicentre, phase 2/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 627-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85).Dutton SJ, Ferry DR, Blazeby JM, et al. Gefitinib for oesophageal cancer progressing after chemotherapy (COG): a phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 894-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86).Xu Y, Zheng Y, Sun X, et al. Concurrent radiotherapy with gefitinib in elderly patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: Preliminary results of a phase II study. Oncotarget 2015; 6: 38429-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]