Significance

Mutations in the glucocerebrosidase gene (GBA) represent the most common genetic risk factor for Parkinson’s disease (PD), affecting 5–10% of patients and accelerating disease progression. Mutations in GBA and consequent loss of enzymatic activity allow glucocerebrosides to build up in cells. Here, we tested an experimental drug that inhibits the production of glucocerebrosides, hypothesizing that producing fewer lipids may counteract the challenge of clearing them from cells. In mice with mutant Gba, prolonged administration of this inhibitor reduced brain glucocerebrosides. In addition, this treatment reduced levels of aggregated α-synuclein, a protein that builds up in PD brains, and improved behavioral responses. The findings suggest that reducing glucocerebrosides might represent a viable therapeutic strategy for PD patients carrying GBA mutations.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, GBA mutations, glucosylceramide synthase, Gaucher disease, Lewy body dementia

Abstract

Mutations in the glucocerebrosidase gene (GBA) confer a heightened risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (PD) and other synucleinopathies, resulting in a lower age of onset and exacerbating disease progression. However, the precise mechanisms by which mutations in GBA increase PD risk and accelerate its progression remain unclear. Here, we investigated the merits of glucosylceramide synthase (GCS) inhibition as a potential treatment for synucleinopathies. Two murine models of synucleinopathy (a Gaucher-related synucleinopathy model, GbaD409V/D409V and a A53T–α-synuclein overexpressing model harboring wild-type alleles of GBA, A53T–SNCA mouse model) were exposed to a brain-penetrant GCS inhibitor, GZ667161. Treatment of GbaD409V/D409V mice with the GCS inhibitor reduced levels of glucosylceramide and glucosylsphingosine in the central nervous system (CNS), demonstrating target engagement. Remarkably, treatment with GZ667161 slowed the accumulation of hippocampal aggregates of α-synuclein, ubiquitin, and tau, and improved the associated memory deficits. Similarly, prolonged treatment of A53T–SNCA mice with GZ667161 reduced membrane-associated α-synuclein in the CNS and ameliorated cognitive deficits. The data support the contention that prolonged antagonism of GCS in the CNS can affect α-synuclein processing and improve behavioral outcomes. Hence, inhibition of GCS represents a disease-modifying therapeutic strategy for GBA-related synucleinopathies and conceivably for certain forms of sporadic disease.

Synucleinopathies refer to the group of neurodegenerative diseases characterized by pathological accumulation of α-synuclein, particularly Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Mutations in the glucocerebrosidase gene (GBA) are the highest genetic risk factor for developing PD and DLB (1, 2). Recent clinical studies indicate that GBA status may also impact the natural history of PD. Patients who harbor GBA mutations present a higher prevalence and severity of bradykinesia, motor complications, and cognitive decline (3–5).

Homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in GBA cause Gaucher disease (GD), which is characterized by the pathological accumulation of lipid substrates of glucocerebrosidase, such as glucosylceramide (GlcCer) and glucosylsphingosine (GlcSph). Reduction of these glycosphingolipids by systemic administration of recombinant glucocerebrosidase (enzyme replacement therapy) or antagonists of glucosylceramide synthase (GCS, substrate reduction therapy) can effectively treat the visceral and hematological manifestations of GD (6). However, the current treatments have no effect on central nervous system (CNS) pathology due to poor entry of the therapeutic agents into the brain. Novel brain-penetrant, orally available inhibitors of GCS have recently been shown to attenuate lipid accumulation in mouse models of neuronopathic GD (7, 8).

Notably, patients with PD without GBA mutations can exhibit lower enzymatic levels of glucocerebrosidase in the CNS, further implicating this lysosomal enzyme in the disease pathogenesis (9, 10). Although glycosphingolipid buildup has not been observed in brain tissues from patients with PD with or without GBA mutations, it is conceivable that substrate accumulation in susceptible neurons might be masked by the more numerous glial cells (11). Small increases in GlcCer have been reported in dopaminergic neurons differentiated from inducible pluripotent stem cells harboring heterozygote GBA mutations and in primary cultured cortical neurons expressing ∼50% glucocerebrosidase activity. Interestingly, these cellular models display increased α-synuclein levels, presumably due to the changes in the sphingolipid composition (12, 13).

The precise mechanism by which GBA mutations increase the risk for developing synucleinopathies and accelerate disease progression remains unknown. Findings from independent studies support a direct role for glucocerebrosidase in the pathogenesis of these devastating diseases (14, 15). The leading hypothesis posits that GBA-mediated loss of function would cause an abnormal glycosphingolipid environment leading to cellular protein mishandling (proteinopathy) and neuronal dysfunction (16). A decrease in glucocerebrosidase activity is thought to induce an increase in CNS α-synuclein/ubiquitin/tau aggregates and to exacerbate behavioral deficits (13, 16–22). These pathological and behavioral aberrations can be ameliorated by virus-mediated overexpression of exogenous glucocerebrosidase in the CNS, which might act by restoring membrane glycosphingolipids (16, 21–23).

In the present study, we describe a CNS-penetrant GCS inhibitor and investigate whether pharmacological reduction of lipid substrates of glucocerebrosidase would affect synucleinopathy features in vivo, despite the apparent lack of GlcCer accumulation. Sustained administration of an orally available inhibitor of GCS significantly decreased α-synuclein pathology and improved behavioral outcomes in two synucleinopathy models (i.e., GbaD409V/D409V, expressing mutant D409V glucocerebrosidase and endogenous α-synuclein; and A53T–SNCA mouse model, overexpressing A53T–α-synuclein and displaying endogenous wild-type murine glucocerebrosidase). The data indicate that brain-penetrant GCS antagonists can modulate α-synuclein homeostasis, thereby reducing the progression of synucleinopathies in mice with and without mutations in Gba.

Results

Brain Penetrant GCS Inhibitor Reduces CNS Glycosphingolipids in GbaD409V/D409V Mice.

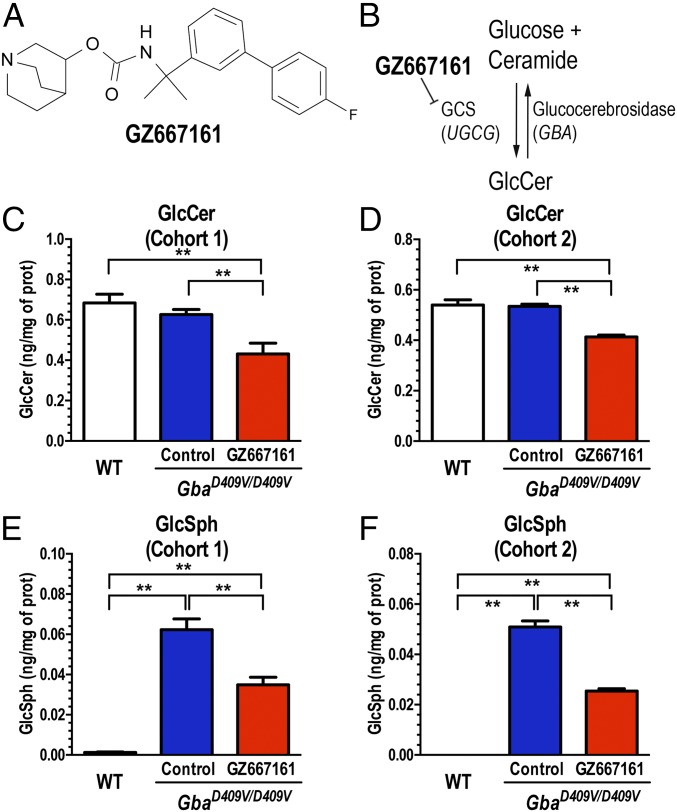

A potent and orally available inhibitor of GCS (GZ667161, Fig. 1 A and B) with good CNS penetrance has recently been shown to be effective at reducing the accumulation of glycolipid substrates in the brain and extending life span in a neuropathic murine model of GD (7). Based on these findings, we first tested the effects of GZ667161 in a mouse model of Gaucher-related synucleinopathy (GbaD409V/D409V) that presents with progressive accumulation of GlcSph and α-synuclein aggregates in the CNS as well as memory deficits (21). Two GbaD409V/D409V cohorts were studied (Fig. S1). In cohort 1 (presymptomatic), drug administration was initiated after GbaD409V/D409V pups were weaned at 4 wk of age and continued until killing at 10 mo of age. GbaD409V/D409V cohort 2 (postsymptomatic) was administered GZ667161 starting at 6 mo of age until killing at 13 mo of age. Mice were fed GZ667161 compounded in their diet (0.033% wt/wt) for the duration of the study; a control littermate group was fed the same diet lacking the small molecule drug. Similar to previous reports (21), GbaD409V/D409V presented no GlcCer accumulation in whole brain lysates compared with wild-type animals, despite displaying 20% residual glucocerebrosidase activity (Fig. 1 C and D). GbaD409V/D409V cortical glucocerebrosidase activity was not affected by GZ667161 treatment (96 ± 5% of control GbaD409V/D409V, n = 11, P = 0.27). Importantly, animals administered the compounded diet exhibited reduced levels of GlcCer in the cerebral cortex (Fig. 1 C and D). GZ667161 administration also reduced cortical GlcSph (Fig. 1 E and F), another glucocerebrosidase-related lipid known to accumulate in GbaD409V/D409V mice (21). These results demonstrate the reduction of glucocerebrosidase substrate glycosphingolipids and confirm the CNS target engagement of the GCS inhibitor.

Fig. 1.

The glucosylceramide synthase (GCS) inhibitor, GZ667161 reduces CNS glycosphingolipids in the mouse model of Gaucher-related synucleinopathy. (A) Structure of GZ667161 (quinuclidin-3-yl-N-[1-[3-(4-fluorophenyl)phenyl]-1-methyl-ethyl]carbamate). (B) Schematic of glucosylceramide synthase inhibition by GZ667161. GbaD409V/D409V mice were fed GZ667161 as described in SI Materials and Methods, littermates were fed a control diet, and age-matched, wild-type untreated mice were positive controls. (C and D) GZ667161 treatment reduced brain GlcCer in GbaD409V/D409V mice (cohorts 1 and 2, Materials and Methods). (E and F) GbaD409V/D409V mice accumulate the glucocerebrosidase substrate, GlcSph, but GZ667161 significantly reduced their GlcSph. The results are represented as means ± SEM, with n ≥ 10 per group (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

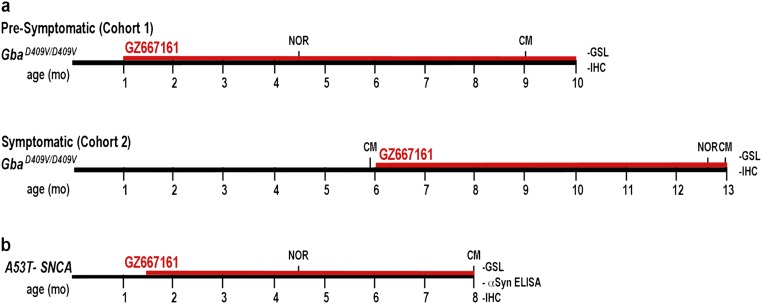

Fig. S1.

Timeline for treatment and endpoints. (A) Two GbaD409V/D409V cohorts were studied. In cohort 1 (presymptomatic), drug administration was initiated after pups were weaned at 4 wk of age and continued until killing at 10 mo of age. GbaD409V/D409V cohort 2 (symptomatic) was administered GZ667161 starting at 6 mo of age until killing at 13 mo of age. (B) A53T–SNCA mice were randomized to GZ667161 or control diet at 6 wk of age. Treatment continued until the end of the study at 8 mo of age. Abbreviations: CM, contextual memory; NOR, novel object recognition; GSL, glycosphingolipid quantification; IHC, immunohistochemistry (Proteinase K-resistant α-synuclein, ubiquitin, and tau).

GZ667161 Ameliorates Cognitive Impairment in the Gba-Related Synucleinopathy Mouse Model.

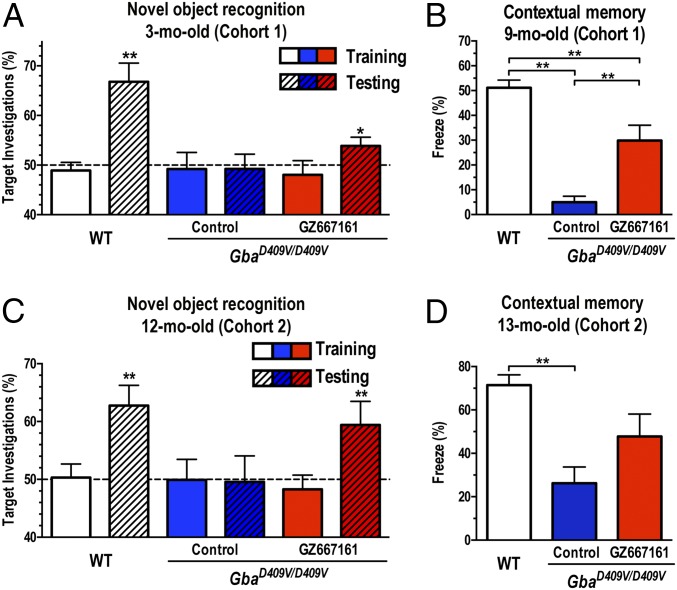

Mutations in GBA are now recognized as an independent risk factor for development of cognitive impairment in patients with PD (24–27). The GbaD409V/D409V mice present several distinct features of synucleinopathies, including cognitive impairment and pathogenic accumulation of α-synuclein, ubiquitin, and tau aggregates (21, 22). The assessment of memory function in GbaD409V/D409V mice treated with GZ667161 for 2 mo with the novel object recognition test revealed a modest but significant improvement in memory function (cohort 1, Fig. 2A). This improvement in cognitive function was confirmed in the same group of animals with another behavioral paradigm that involved placing the mice in a fear-conditioning chamber, exposing them to a noxious stimulus, and then testing the animals’ context-specific responses (freezing) after 24 h. GbaD409V/D409V mice treated with GZ667161 for 8 mo showed a greater tendency to display a freezing response in the contextual fear test, indicating greater memory recall than that in the control group (Fig. 2B). Treatment of wild-type mice with GZ667161 had no effect on context-specific responses despite similar GlcCer reduction as in GbaD409V/D409V animals (Fig. S2), suggesting that GCS inhibition does not affect memory in animals with normal cognitive function.

Fig. 2.

GCS inhibition ameliorates memory deficits in a mouse model of Gaucher-related synucleinopathy. Two independent randomized cohorts of GbaD409V/D409V mice received GZ667161 or control diet. Age-matched WT mice served as positive controls. (A) Cohort 1 mice were subjected to the novel object recognition test 2 mo after treatment initiation. None of the groups showed an object preference after exposure to two identical objects during training (clear white, blue, and red bars). After 24 h, the mice were presented with a novel object. In the testing trial (hatched bars), WT mice investigated the novel object significantly more (P < 0.01), GbaD409V/D409V mice (blue hatched bar) showed no preference for the novel object (cognitive impairment), and GZ667161-treated GbaD409V/D409V mice showed a modest but significant increase in investigation of the novel target (red hatched bars, P < 0.05). (B) The memory impairment of cohort 1 GbaD409V/D409V mice was corroborated by decreased freezing responses in the contextual fear conditioning test at 9 mo of age (blue bar, P < 0.05), whereas littermate mice treated with GZ667161 showed a better contextual memory response (red bar). (C and D) Cognitively impaired GbaD409V/D409V mice were randomized to receive GZ667161 (n = 15) or control diet (n = 14) from 6 to 13 mo of age (cohort 2, symptomatic). GZ667161 treatment attenuated the memory impairment in the novel object recognition and contextual fear tasks. The horizontal line demarcates 50% target investigations, which represents no preference for either object. The results are represented as means ± SEM, with n ≥ 10 per group (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

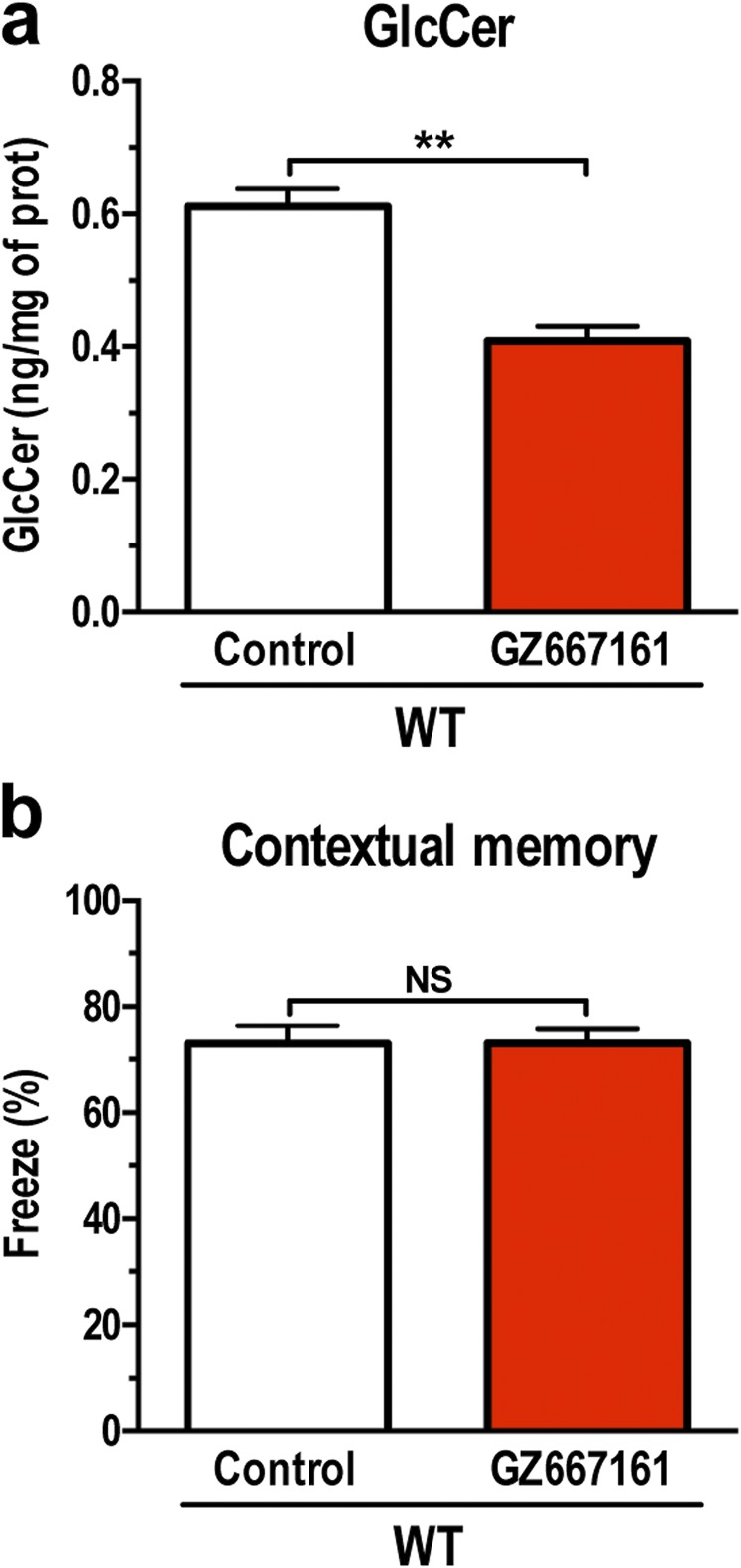

Fig. S2.

The glucosylceramide synthase (GCS) inhibitor, GZ667161, reduces CNS glucosylceramide and does not affect memory in wild-type animals. C57BL/6 mice were fed GZ667161 as described in SI Materials and Methods, littermates were fed a standard control diet. (A) Treatment with GZ667161 reduced brain GlcCer. (B) Treatment of wild-type mice with GZ667161 did not affect the contextual memory response. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (t test, **P < 0.01, significantly different from one another). NS, not significant.

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of GCS inhibition, we next tested whether the improvement in cognition could also be realized when administered at a clinically relevant postsymptomatic stage (cohort 2). Testing of 6-mo-old GbaD409V/D409V mice before treatment confirmed their contextual memory impairment (contextual freezing response, WT: 59 ± 3%, n = 10; GbaD409V/D409V: 24 ± 7%, n = 9, P < 0.01). The remainder of the GbaD409V/D409V littermates was randomly assigned to a control group (n = 12) or a GCS inhibitor treatment group (GZ667161, n = 11). Memory function was then evaluated through novel object recognition and contextual fear tests at 12 and 13 mo, respectively. Remarkably, treatment of GbaD409V/D409V mice with GZ667161 attenuated memory deficits as assessed with both cognitive tasks, whereas GbaD409V/D409V mice treated with the control diet showed no discernible improvement (Fig. 2 C and D). Together, the results from these independent cohorts using two different cognitive assessments indicated that GCS inhibition and consequent modulation of lipid homeostasis could not only prevent the development of cognitive deficits but also reverse specific behavioral dysfunction in the mouse model of Gaucher-related synucleinopathy.

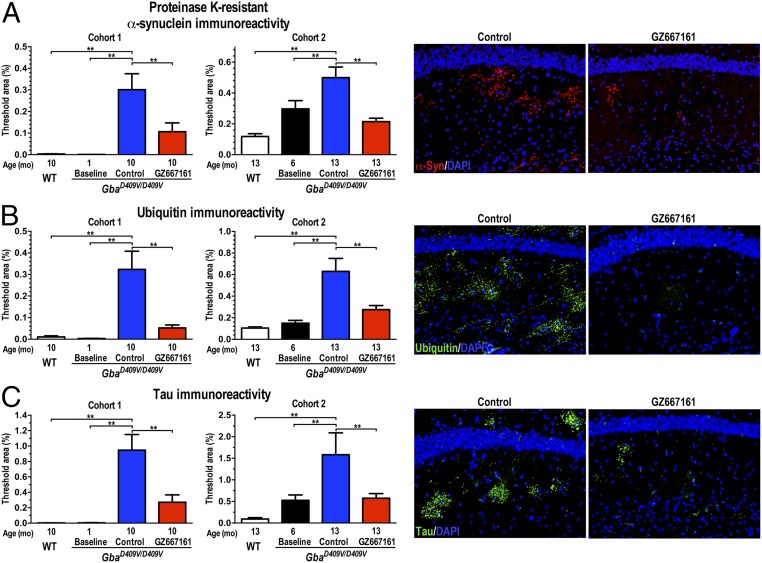

GZ667161 Reduces Pathological Aggregate Accumulation in the Gba-Related Synucleinopathy Mouse Model.

Although the precise pathologies of PD and DLB remain unclear, the findings of progressive accumulation of α-synuclein and other proteins in LBs have implicated protein misfolding as a potential causative mechanism (28, 29). This proteinopathy is replicated in the GbaD409V/D409V mouse model of Gaucher disease, which shows a progressive accumulation of neuronal proteinase K-resistant α-synuclein, ubiquitin, and tau aggregates in the CNS (22). We therefore evaluated the effect of GCS inhibition on the accumulation of pathological aggregates by immunohistochemical morphometric analyses (21). Quantification of proteinase K-resistant α-synuclein, ubiquitin, and tau aggregates in the mouse hippocampus confirmed the progressive accumulation of pathological aggregates during the 9-mo study (GbaD409V/D409V baseline vs. control, Fig. 3 A–C). Remarkably, treatment of GbaD409V/D409V mice with GZ667161 led to significantly lower amounts of hippocampal proteinase K-resistant α-synuclein, ubiquitin, and tau aggregates (Fig. 3 A–C). Similar results were observed in an independent study (cohort 2) of symptomatic GbaD409V/D409V mice treated with GZ667161 starting at 6 mo of age (Fig. 3 A–C). These data demonstrated that a brain-penetrant GCS inhibitor can modify the proteostatic processing of these endogenous proteins and reduce the accumulation of pathologically misfolded protein aggregates. The data also support the contention that decreased glucocerebrosidase activity promotes α-synuclein misprocessing through abnormal lipid processing and that GZ667161-mediated remodeling of the glycosphingolipid cell membrane environment can reduce the pathological and behavioral aberrations associated with GBA-mediated synucleinopathies.

Fig. 3.

GCS inhibition reduces pathological aberrations in a mouse model of Gaucher-related synucleinopathy. Brain sections from WT and GbaD409V/D409V mice were stained for proteinase K-resistant α-synuclein (A), ubiquitin (B), and tau (C) aggregates. GZ667161 reduced aggregated protein levels of GbaD409V/D409V mice. The representative images (Right) show proteinase K-resistant α-synuclein immunoreactivity (A, red), ubiquitin (B, green), and tau (C, green) in the hippocampi of GZ667161-treated and control GbaD409V/D409V mice of cohort 1. DAPI-stained cell nuclei fluoresce blue. All data represent the mean ± SEM, with n ≥ 8 per group (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

Brain Penetrant GCS Inhibitor Reduces CNS Glucosylceramide in a Synucleinopathy Model.

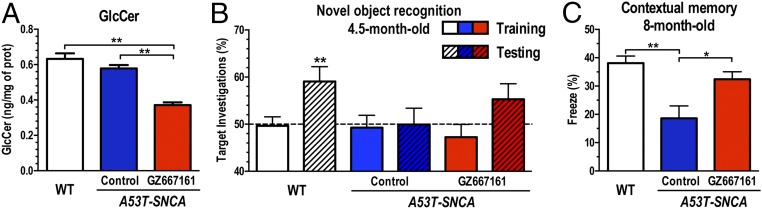

To illustrate further the therapeutic potential of GCS inhibition to reduce the accumulation of misfolded α-synuclein aggregates, we next evaluated the efficacy of GZ667161 in A53T–SNCA mice, a well-characterized mouse model of synucleinopathy without mutations in Gba. A53T–SNCA mice express human A53T α-synuclein and carry wild-type alleles of Gba (30). Brains of A53T–SNCA mice exhibit lower glucocerebrosidase activity (∼80% residual activity) and no apparent glycosphingolipid accumulation, similar to patients with PD expressing wild-type GBA alleles (11, 16). Transgenic mice were fed GZ667161 (compounded in their diet at 0.033% wt/wt) starting at 6 wk of age. Mice were killed at 8 mo of age, and the levels of glycosphingolipids were quantified by mass spectrometry. A53T–SNCA cortical glucocerebrosidase activity was not affected by GZ667161 treatment (102 ± 4% of control A53T–SNCA, n = 12, P = 0.37). Treatment with GZ667161 reduced the levels of GlcCer in the cerebral cortex, indicating that the GCS inhibitor effectively reduced the synthesis of this glycosphingolipid in the CNS of these animals (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

GCS inhibition reduces GlcCer and affects cognition in the A53T–SNCA mouse model of synucleinopathy. A53T–SNCA mice were fed GZ667161 from 6 wk of age to 8 mo. Equivalent littermates were fed a control diet to monitor disease progression, and age-matched untreated WT mice were positive controls. (A) GZ667161 treatment reduced brain GlcCer in A53T–SNCA mice. (B) All mice subjected to the novel object recognition test at 4.5 mo of age showed no object preference after exposure to two identical objects during training (clear white, blue, and red bars). WT mice investigated the novel object significantly more frequently than A53T–SNCA mice (white hatched bars, P < 0.01), but A53T–SNCA mice (blue hatched bar) showed no such preference, indicating cognitive impairment. GZ667161-treated A53T–SNCA mice showed a nonsignificant trend toward cognitive improvement (red hatched bars, P = 0.11). (C) The memory impairment of A53T–SNCA mice was corroborated by a decreased freezing response in the contextual fear-conditioning test at 8 mo of age (blue bar, P < 0.05). Treatment of A53T–SNCA mice with GZ667161 significantly attenuated the contextual memory responses at this later time point (red bars, P < 0.05). Bars with different letters are significantly different from one another (P < 0.05). All data represent the mean ± SEM, with n ≥ 10 per group (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

GZ667161 Ameliorates Cognitive Impairment in a Synucleinopathy Mouse Model.

Next, we examined the ability of GCS inhibition to influence cognitive function in A53T–SNCA mice. Animals were tested for novel object recognition initially at 3 mo posttreatment with GZ667161. A53T–SNCA mice treated with GZ667161 showed a trend toward an improved response in this test (Fig. 4B). This trend was confirmed when the mice were retested at a later time point using conditioned fear testing. A53T–SNCA mice treated with GZ667161 for 6.5 mo showed a significantly improved contextual response (Fig. 4C), which indicated that inhibition of GCS alleviated the aberrant cognitive response in a murine model of synucleinopathy.

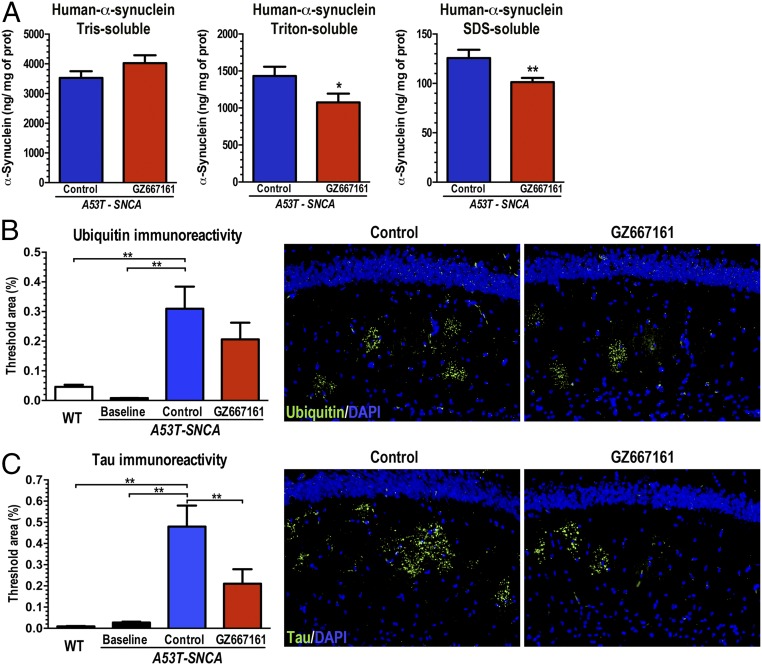

GZ667161 Affects α-Synuclein Proteostasis in a Synucleinopathy Mouse Model.

We then evaluated whether GCS inhibition would affect the subcellular localization of α-synuclein in A53T–SNCA mice. Previously, our group has shown that glucocerebrosidase augmentation can affect α-synuclein cellular distribution in A53T–SNCA mice. Cortical tissue homogenates from A53T–SNCA mice were subjected to serial fractionation to separate the cytosolic-soluble, membrane-associated, and cytosolic-insoluble forms of α-synuclein (18). No changes in the levels of cytosolic soluble α-synuclein were observed in the CNS of GZ667161-treated mice (Tris sol: 114 ± 8% of control, n = 14, P = 0.17, Fig. 5A). However, the levels of the membrane-associated and insoluble α-synuclein species were significantly decreased in response to GZ667161 treatment (Triton sol: 75 ± 8% of control, n = 14, P < 0.05; SDS soluble: 81 ± 3% of control, n = 14, P < 0.01; Fig. 5A), suggesting that the GZ667161-mediated reduction in glycosphingolipids affected the subcellular distribution of α-synuclein. Recent studies have demonstrated that alterations in lipid membrane composition can greatly affect the kinetics of α-synuclein membrane-induced aggregation (31, 32).

Fig. 5.

GCS inhibition affects α-synuclein membrane distribution and reduces pathological aberrations in the A53T–SNCA mouse model of synucleinopathy. A53T–SNCA mice were randomized to receive GZ667161 or control diet (n = 12 in each group) from 6 wk of age to 8 mo. Homogenized cerebral cortices provided cytosolic and membrane-associated fractions. (A) GCS inhibition decreased human α-synuclein in the membrane-associated fractions (red bars; P < 0.05). (B and C) GZ667161 reduced accumulation of hippocampal aggregated ubiquitin (B) and tau (C) in these mutant mice, with littermates killed at 6 wk of age to provide a histological baseline (n = 6). The images show ubiquitin (B, green) and tau (C, green) immunoreactivity in hippocampi of control or GZ667161-treated 8-mo-old A53T–SNCA mice. DAPI stains cell nuclei blue. All data represent the mean ± SEM, with n ≥ 8 per group (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

GZ667161 Reduces Pathological Aggregate Accumulation in a Synucleinopathy Mouse Model.

Concurrence of tau-, ubiquitin- and α-synuclein–associated pathology frequently occurs in patients with PD and DLB (33–35). We therefore evaluated the effect of GZ667161 on the accumulation of pathological aggregates in the A53T–SNCA mouse model by immunohistochemical morphometric analyses (21). Quantification of ubiquitin and tau aggregates in the mouse hippocampus confirmed the progressive accumulation of pathological aggregates during the 7-mo study (A53T–SNCA baseline vs. control, Fig. 5 B and C). Also, immunohistochemical staining of hippocampal sections of A53T–SNCA animals for ubiquitin and tau revealed a marked reduction in aggregate pathology in animals exposed to the GCS inhibitor GZ667161 (Fig. 5 B and C). Immunostaining for proteinase K-resistant α-synuclein in A53T–SNCA mice failed to reveal a distinct signal, presumably due to the large amounts of exogenous human α-synuclein. Importantly, treatment with the GCS inhibitor reduced human α-synuclein levels in membrane-associated fractions (Fig. 5A), analogous to the effects on accumulation of mouse endogenous tau and ubiquitin aggregates (Fig. 5 B and C). These results affirmed that a reduction in glycosphingolipids in the CNS limited the development of abnormal pathological inclusions in a synucleinopathy animal model expressing wild-type glucocerebrosidase.

Discussion

The link between synucleinopathies (including PD and DLB) and GBA mutations has been consolidated in recent years. It is now widely accepted that disease-segregating mutations in GBA not only increase the risk of PD and DLB but, more importantly, they accelerate the progression of these diseases (3–5, 14, 24–27). Although the precise mechanistic basis of GBA-mediated PD remains unknown, clinical and experimental evidence indicates that glucocerebrosidase haploinsufficiency, as a result of GBA mutations, can interfere with α-synuclein processing and contribute to the pathological accumulation of the protein (10, 15, 16). The present studies support this premise by demonstrating that a reduction in glucocerebrosidase-related lipids (through a brain-penetrant GCS antagonist) can improve behavioral and pathological defects in synucleinopathy mouse models.

Patients who harbor GBA mutations present a faster deterioration of cognitive functions (25–27). Similarly, partial reduction in brain glucocerebrosidase activity can exacerbate cognitive deficits in animal models (16, 21). The GbaD409V/D409V mouse model recapitulates many of the aberrant biochemical characteristics noted in brains from patients with PD and DLB and also features measurable deficits in memory. Because few patients carrying GBA mutations will develop cognitive impairment, it was relevant to evaluate whether the salutary effects can also be realized in animals with overt disease. GCS inhibition in both early and late symptomatic GbaD409V/D409V mice was effective in reversing cognitive impairment. This recovery in cognition was associated with reduction in glycosphingolipids levels and a measurable decline in the accumulation of pathological aggregates. Remodeling of the neuronal glycosphingolipid topography may possibly improve lysosomal function, a requirement for correct synaptic activity and proper functioning of pathways that degrade aggregated proteins (31, 36, 37). These results strongly suggest that brain-penetrant GCS inhibitors may impede progression of (and perhaps even reverse) some aspects of Gaucher-related parkinsonism and associated synucleinopathies.

The pathological hallmark of PD and DLB is the accumulation of α-synuclein within Lewy bodies and neurites of the nervous system (38). α-Synuclein is an intrinsically disordered protein that has been implicated in vesicle trafficking and in synaptic plasticity of neurons (31). The interaction between α-synuclein and lipid surfaces is key to mediating its normal function, and alterations in the lipid membrane composition can trigger the formation of pathological amyloid fibrils (31, 39). For example, changes in the composition of sphingolipids have been reported to stabilize soluble oligomeric forms of isolated recombinant α-synuclein (13). Endogenously produced α-synuclein can also accumulate in induced pluripotent (iPS) cells from patients with PD who harbor homozygous or heterozygous GBA mutations, presumably because of the presence of increased levels of membrane glycosphingolipids (12, 13, 40). It appears reasonable, then, that persistent reduction in brain glycosphingolipids of the synucleinopathy animal slowed the accumulation of aggregated proteins (ubiquitin, α-synuclein, and tau), indicating the potential for the orally available brain-penetrant GCS inhibitor to modify disease progression in patients with PD carrying GBA mutations.

The precise mechanisms underlying PD pathogenesis are still unknown. Functional studies of PD-associated genes support a central pathogenic role of lysosomal pathways (41). GBA mutations result in reduced lysosomal glucocerebrosidase activity. However, it is unclear whether alternative lysosomal insults might affect glucocerebrosidase-related lipid accumulation and, therefore, be responsive to GCS inhibition. A number of patients with PD without mutations in GBA exhibit lower levels of CNS glucocerebrosidase activity, suggesting a role for this lysosomal enzyme in disease despite the lack of apparent lipid accumulation (9, 11). Similarly, the A53T–SNCA mice present reduced glucocerebrosidase activity and no evident glycosphingolipid accumulation (16, 22). Prolonged treatment with the GCS inhibitor improved behavioral endpoints, modulated α-synuclein homeostasis, and reduced the accumulation of ubiquitin and tau aggregates in this animal model expressing wild-type glucocerebrosidase, suggesting that the therapeutic benefit might also extend to patients displaying reduced glucocerebrosidase activity despite carrying wild-type GBA alleles.

GCS inhibitors have been proven safe and tolerable in the clinical setting (42). Translation of the present findings to the GBA-PD patient population will require identification of a prodromal or early symptomatic patient population (to restore function of impaired neurons before their demise) and potentially lengthy clinical trials (due to the slow and variable disease progression and current lack of disease progression biomarkers).

In summary, the present findings demonstrate that reducing the levels of CNS glycosphingolipids by antagonizing GCS corrected the hallmark pathological and functional phenotypes in two animal models of synucleinopathy. Glucocerebrosidase deficiency [due to GBA mutations (1, 21) or α-synuclein–mediated inhibition (9, 13)] can lead to altered glycosphingolipid homeostasis, consequent α-synuclein misprocessing and intracellular deposition, generalized proteinopathy, and the development of behavioral deficits. Reducing the levels of glycosphingolipids through GCS inhibition disrupted the pathogenic cycle of aberrant protein aggregation and functional deficits. Together, the data presented herein provide robust in vivo evidence supporting GCS inhibition as a novel disease-modifying therapeutic approach for GBA-related synucleinopathies, including PD, and support the advancement of GCS antagonists toward clinical testing.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Sanofi approved all procedures. Experimental details regarding animal use are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Administration of the Glucosylceramide Synthase Inhibitor GZ667161.

A subset of animals received the glucosylceramide synthase inhibitor GZ667161 through their pelleted diet [0.033% (wt/wt)]. In each experimental cohort, sex and sibling were randomly matched for group assignment. GbaD409V/D409V cohort 1 drug administration was initiated after pups were weaned at 4 wk of age and was continued until killing at 10 mo of age. GbaD409V/D409V cohort 2 were administered GZ667161 starting at 6 mo of age until killing at 13 mo of age. A53T–SNCA mice were exposed to the drug starting at 6 wk of age until killing at 8 mo.

Measurement of Glycosphingolipid Levels and Glucocerebrosidase Activity.

These procedures are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Behavioral Tests.

The novel object recognition and fear conditioning tests are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Immunohistochemistry and Morphometric Analysis.

These procedures are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Fractionation and Quantification of α-Synuclein.

Cerebral cortices from A53T–SNCA mice were homogenized as described (18) to obtain three fractions: cytosolic (Tris soluble), membrane-associated (Triton X-100 soluble), and insoluble (SDS soluble). The concentration of human α-synuclein in the various fractions was quantified by sandwich ELISA (Invitrogen). Protein concentration was determined by the Pierce microBCA assay (Thermo Fisher).

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed with Student’s t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Newman–Keuls post hoc test. Preference for novelty was defined as investigating the novel object more than 50% of the time, as assessed with a one-sample t test. All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism v4.0 (GraphPad Software). Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

SI Materials and Methods

Animals.

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Sanofi approved all procedures. Animals were individually housed under light:dark (12:12 h) cycles and provided with food and water ad libitum. The GbaD409V/D409V mouse model of Gaucher disease (GD) harbors a point mutation at residue 409 in the murine glucocerebrosidase (Gba) gene (41). The A53T–SNCA transgenic mice were engineered to express mutant human A53T α-synuclein (line M83) under the transcriptional control of the murine PrP promoter (29).

Measurement of Glycosphingolipid Levels and Glucocerebrosidase Activity.

Tissue levels of glucosylceramide (GlcCer, C18:0) and glucosylsphingosine (GlcSph) were measured by liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) as previously described (22). Briefly, brain tissue homogenates were extracted with 1 mL of an organic solvent mixture. The extracted sphingolipids (GlcCer and GlcSph) were directly separated by hydrophilic liquid chromatography (Atlantis and BEH Hilic columns, respectively; Waters), analyzed by triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometry (API 5000, Applied Biosystems/MDS SCIEX; and Agilent 6490, Agilent Technologies, respectively), and compared with sphingolipid standards (Matreya). Brain glucocerebrosidase activities were determined as described using 4-methylumbelliferyl (4-MU)-β-d-glucoside as the artificial substrate (22).

Immunohistochemistry.

For the histological analysis, the mice were perfused with cold PBS. Brains were removed and postfixed in 10% (vol/vol) neutral buffered formalin for 48 h. Tissues were then placed in 30% (vol/vol) sucrose, embedded, and sliced into 20-μm sections with a cryostat. Some tissues were pretreated with proteinase K (1:4 dilution; DAKO) for 7 min at room temperature to expose α-synuclein and other aggregated proteins (22). Brain sections were blocked with 10% (vol/vol) serum for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with the following antibodies: mouse anti-ubiquitin (1:500; Millipore), rabbit anti–α-synuclein (1:300; Sigma), and mouse anti-tau (1:500, Tau-5; Millipore). Brain sections were then incubated for 1 h with either a donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor-488 or donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor-555 secondary antibody (1:250 dilution; Invitrogen). For α-synuclein aggregate quantification, a cyanine 3-tyramide signal amplification kit was used (PerkinElmer). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (Sigma). Sections were coverslipped with aqua-poly/mount (Polysciences).

Morphometric Analysis.

Sections were imaged with a SPOT camera (Diagnostic Instruments) paired with a Nikon Eclipse E800 fluorescence microscope equipped with a 20× objective lens. The stratum radiatum external to the CA1 hippocampal cell body layer was imaged for each animal. Two or three sections were imaged per animal. All images were exposure matched for Metamorph analysis (Molecular Devices). These procedures were performed blinded to the genotype or treatment. The percent threshold area was calculated and expressed as the mean ± SEM.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M. Cromwell and J. Leonard for providing GZ667161; L. Shen and W. Korfmacher for GZ667161 quantification; and T. Taksir, N. Panarello, E. Helger, F. Morshed, H. Klodnitsky, R. Karolides, R. Serriello, L. Curtin, and J. Fagan for technical assistance and support.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: S.P.S., C.V., J.C., C.M.T., A.M.R, H.P., M.A.O., J.C.D., J.M., E.M., B.W., S.H.C., and L.S.S. are employees of Sanofi.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1616152114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sidransky E, et al. Multicenter analysis of glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(17):1651–1661. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nalls MA, et al. A multicenter study of glucocerebrosidase mutations in dementia with Lewy bodies. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(6):727–735. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beavan MS, Schapira AH. Glucocerebrosidase mutations and the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease. Ann Med. 2013;45(8):511–521. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2013.849003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cilia R, et al. Survival and dementia in GBA-associated Parkinson’s disease: The mutation matters. Ann Neurol. 2016;80(5):662–673. doi: 10.1002/ana.24777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu G, et al. International Genetics of Parkinson Disease Progression (IGPP) Consortium Specifically neuropathic Gaucher’s mutations accelerate cognitive decline in Parkinson’s. Ann Neurol. 2016;80(5):674–685. doi: 10.1002/ana.24781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pastores GM, Hughes DA. In: Gaucher Disease. Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews, University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cabrera-Salazar MA, et al. Systemic delivery of a glucosylceramide synthase inhibitor reduces CNS substrates and increases lifespan in a mouse model of type 2 Gaucher disease. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall J, et al. CNS-accessible inhibitor of glucosylceramide synthase for substrate reduction therapy of neuronopathic Gaucher disease. Mol Ther. 2016;24(6):1019–1029. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gegg ME, et al. Glucocerebrosidase deficiency in substantia nigra of parkinson disease brains. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(3):455–463. doi: 10.1002/ana.23614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schapira AH, Chiasserini D, Beccari T, Parnetti L. Glucocerebrosidase in Parkinson’s disease: Insights into pathogenesis and prospects for treatment. Mov Disord. 2016;31(6):830–835. doi: 10.1002/mds.26616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gegg ME, et al. No evidence for substrate accumulation in Parkinson brains with GBA mutations. Mov Disord. 2015;30(8):1085–1089. doi: 10.1002/mds.26278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schöndorf DC, et al. iPSC-derived neurons from GBA1-associated Parkinson’s disease patients show autophagic defects and impaired calcium homeostasis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4028. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazzulli JR, et al. Gaucher disease glucocerebrosidase and α-synuclein form a bidirectional pathogenic loop in synucleinopathies. Cell. 2011;146(1):37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sidransky E, Lopez G. The link between the GBA gene and parkinsonism. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(11):986–998. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70190-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sardi SP, Cheng SH, Shihabuddin LS. Gaucher-related synucleinopathies: The examination of sporadic neurodegeneration from a rare (disease) angle. Prog Neurobiol. 2015;125:47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rockenstein E, et al. Glucocerebrosidase modulates cognitive and motor activities in murine models of Parkinson’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(13):2645–2660. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manning-Boğ AB, Schüle B, Langston JW. Alpha-synuclein-glucocerebrosidase interactions in pharmacological Gaucher models: A biological link between Gaucher disease and parkinsonism. Neurotoxicology. 2009;30(6):1127–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cullen V, et al. Acid β-glucosidase mutants linked to Gaucher disease, Parkinson disease, and Lewy body dementia alter α-synuclein processing. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(6):940–953. doi: 10.1002/ana.22400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu YH, et al. Accumulation and distribution of α-synuclein and ubiquitin in the CNS of Gaucher disease mouse models. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;102(4):436–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fishbein I, Kuo YM, Giasson BI, Nussbaum RL. Augmentation of phenotype in a transgenic Parkinson mouse heterozygous for a Gaucher mutation. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 12):3235–3247. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sardi SP, et al. CNS expression of glucocerebrosidase corrects alpha-synuclein pathology and memory in a mouse model of Gaucher-related synucleinopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(29):12101–12106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108197108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sardi SP, et al. Augmenting CNS glucocerebrosidase activity as a therapeutic strategy for parkinsonism and other Gaucher-related synucleinopathies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(9):3537–3542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220464110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rocha EM, et al. Glucocerebrosidase gene therapy prevents α-synucleinopathy of midbrain dopamine neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;82:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alcalay RN, et al. Cognitive performance of GBA mutation carriers with early-onset PD: The CORE-PD study. Neurology. 2012;78(18):1434–1440. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318253d54b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winder-Rhodes SE, et al. Glucocerebrosidase mutations influence the natural history of Parkinson’s disease in a community-based incident cohort. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 2):392–399. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brockmann K, et al. GBA-associated Parkinson’s disease: Reduced survival and more rapid progression in a prospective longitudinal study. Mov Disord. 2015;30(3):407–411. doi: 10.1002/mds.26071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oeda T, et al. Impact of glucocerebrosidase mutations on motor and nonmotor complications in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(12):3306–3313. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee VM, Giasson BI, Trojanowski JQ. More than just two peas in a pod: Common amyloidogenic properties of tau and alpha-synuclein in neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27(3):129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Molecular pathways of neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2003;302(5646):819–822. doi: 10.1126/science.1087753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giasson BI, et al. Neuronal alpha-synucleinopathy with severe movement disorder in mice expressing A53T human alpha-synuclein. Neuron. 2002;34(4):521–533. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bendor JT, Logan TP, Edwards RH. The function of α-synuclein. Neuron. 2013;79(6):1044–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galvagnion C, et al. Chemical properties of lipids strongly affect the kinetics of the membrane-induced aggregation of α-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(26):7065–7070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601899113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKeith IG, et al. Consortium on DLB Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duda JE, et al. Concurrence of alpha-synuclein and tau brain pathology in the Contursi kindred. Acta Neuropathol. 2002;104(1):7–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0563-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giasson BI, et al. Initiation and synergistic fibrillization of tau and alpha-synuclein. Science. 2003;300(5619):636–640. doi: 10.1126/science.1082324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scott D, Roy S. α-Synuclein inhibits intersynaptic vesicle mobility and maintains recycling-pool homeostasis. J Neurosci. 2012;32(30):10129–10135. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0535-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cremades N, et al. Direct observation of the interconversion of normal and toxic forms of α-synuclein. Cell. 2012;149(5):1048–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Hasegawa M, Goedert M. alpha-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with lewy bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(11):6469–6473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galvagnion C, et al. Lipid vesicles trigger α-synuclein aggregation by stimulating primary nucleation. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(3):229–234. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodard CM, et al. iPSC-derived dopamine neurons reveal differences between monozygotic twins discordant for Parkinson’s disease. Cell Reports. 2014;9(4):1173–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tofaris GK. Lysosome-dependent pathways as a unifying theme in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2012;27(11):1364–1369. doi: 10.1002/mds.25136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cox TM, et al. Eliglustat compared with imiglucerase in patients with Gaucher’s disease type 1 stabilised on enzyme replacement therapy: A phase 3, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9985):2355–2362. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]